Over 20 years ago, on Feb. 12, 1994, Sue Rodriguez died in my arms in her Saanich, British Columbia home. Over the three years following her diagnosis, Sue had been living with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and had fought with passion and determination for the right to choose when she should die and to have a physician’s assistance in dying. When the Supreme Court of Canada ruled against her on Sept. 30, 1993, by a narrow 5–4 majority, she quietly said to me, “The Court may have spoken, but I have the last word.” Any doctor who supported her, however, risked prosecution under section 251 of the Criminal Code and a lengthy prison term. The Canadian Medical Association’s (CMA’s) official position on the issue was to strongly oppose any change in the law.

Despite this, I heard from physicians across the country who strongly supported Sue in her efforts to change the law, many of whom shared stories from their own personal experiences of the cruelty and injustice of the current law. It was also clear that doctors were in fact quietly honouring the requests of terminally ill patients to support them in their desire to end their lives at the time of their choosing, despite the risk of prosecution. Sue was fortunate to have the support of one such doctor.

Sue strongly supported palliative care and pain management, but she also noted that even the best quality palliative care did not always relieve pain, suffering and anguish. And if it did, too often the price to be paid was living like a “zombie,” in her words. She also argued that giving terminally ill people the option to choose the time of their death would mean that many would live longer lives, dying a natural death, instead of ending their life earlier while still physically able to do so without the assistance of a doctor.

Today, if she were still alive, Sue would face a very different landscape. Twenty years after her death, we are now able to witness the actual impact of changes in the law in several jurisdictions, including Oregon. As BC Supreme Court Justice Lynn Smith wrote in her powerful 2012 decision decriminalizing physician-assisted suicide in Carter v. Canada (Attorney General), it is clear that the dire “slippery slope” predictions of those opposed to a change in the law have not come to pass. Only a very small number of terminally ill patients have chosen to end their lives with the assistance of a doctor, and only under very tightly controlled circumstances.

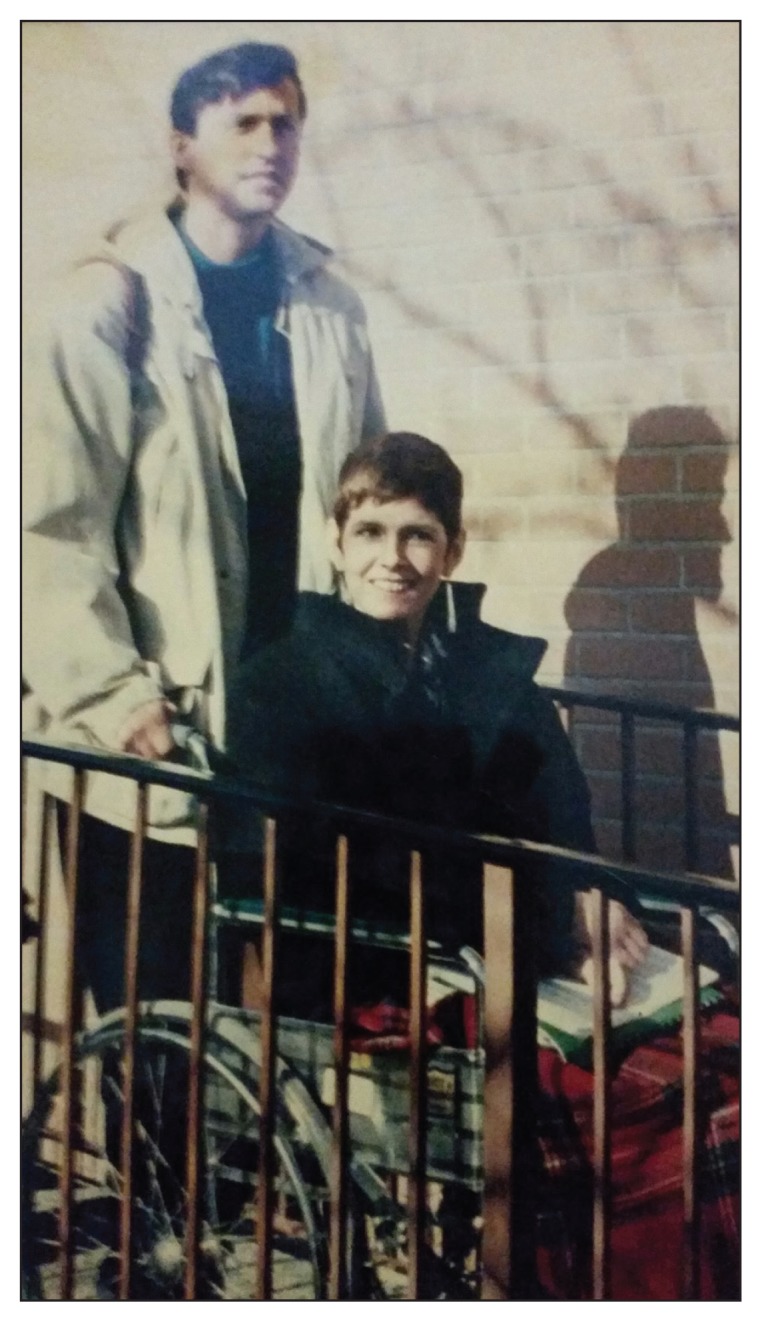

Svend Robinson and Sue Rodriguez at a February 1993 press conference.

Image courtesy of Courtesy of Svend Robinson

If Sue were living in Quebec today, she would have the right to the support of a physician to end her life. The National Assembly of Québec voted, by a large majority in favour of Bill 52, to allow physician-assisted death. Quebec is leading on this fundamental social-justice issue, just as they did three decades earlier on the issue of access to safe abortion. It took a courageous doctor, Henry Morgentaler, to challenge that law. No such doctor has emerged to lead the struggle to change the law on assisted suicide in Canada. Certainly, many were moved by the eloquent and passionate plea of respected SARS doctor, Donald Low, before his own death. As he said, “A lot of clinicians have opposition to dying with dignity. I wish they could live in my body for 24 hours, and I think they would change that opinion.”

The CMA is still grappling with the issue; however, at its annual meeting in August, delegates voted to support “the right of all physicians, within the bounds of existing legislation, to follow their conscience when deciding whether to provide medical aid in dying as defined in CMA’s policy on euthanasia and assisted suicide.” Incoming CMA President Dr. Chris Simpson noted that there are some forms of suffering that even the best end-of-life care can’t alleviate.

The Supreme Court of Canada will once again be considering this issue, as the Carter v. Canada appeal begins in October. Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin, who was one of the four dissenting judges in Sue’s appeal in 1993, will preside. Courts, politicians and yes, physicians and the CMA, have come a long way in the past 20 years in understanding and accepting the need to change the law on assisted suicide. One can only hope that this time, the Supreme Court will support the struggle waged with such courage and dignity by Sue Rodriguez over 20 years ago.

Do you have an opinion about this article? Post your views at www.cmaj.ca. Potential Salon contributors are welcome to send a query to salon@cmaj.ca.