Abstract

Introduction:

The risk of urolithiasis post-Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) surgery is higher when compared to the general population. Calcium and vitamin D supplementation is routinely prescribed to these patients, yet compliance with these supplements is unknown. The aim of this study was to assess the incidence of symptomatic de novo urolithiasis post-RYGB and compliance with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Methods:

A standardized telephone questionnaire was administered to patients who underwent RYGB between 1996 and 2011. Personal and medical histories were obtained with emphasis on episodes of symptomatic urolithiasis and calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Results:

The response rate was 48% with 478 patients completing the telephone questionnaire. After a mean follow-up of 7.0 years (range: 1–15), the incidence of post-RYGB symptomatic urolithiasis was 7.3%, while the rate of de novo symptomatic urolithiasis was 5%. The overall median time to present with symptomatic urolithiasis was 3.1 years, with 3.3 years for de novo stone-formers, and 2.0 years for recurrent stone-formers (p = 0.38). In de novo stone-formers, 33% presented with symptomatic urolithiasis 4 to 14 years postoperatively. Compliance with calcium and vitamin D supplementation was 56% and 51%, respectively.

Conclusions:

Despite recall bias and lack of confirmatory imaging studies, a high postoperative incidence of symptomatic urolithiasis was found in a large sample of post-RYGB patients. A third of patients with de novo stones, presented with symptomatic urolithiasis 4 to 14 years postoperatively. Compliance with postoperative calcium and vitamin D supplementation was poor and needs improvement.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery has been experiencing a steep rise in popularity as a treatment for severe obesity. The National Institutes of Health recommends this intervention for patients with a body mass index (BMI) of at least 40, or 35 with severe comorbidities, such as diabetes mellitus. These procedures are highly effective leading to considerable weight loss and decreased morbidity and mortality.1–3 Considering the number of patients undergoing these procedures has increased, developing a thorough understanding of the associated risks is critical.

Recent studies have reported an elevated risk of kidney stone formation in patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery (RYGB), but not restrictive procedures, such as sleeve gastrectomy or adjustable gastric banding.4–6 RYGB increases urinary oxalate excretion and decreases urinary citrate, conditions commonly associated with the development of calcium oxalate stones.7–9 Indeed, calcium oxalate stones comprise 75% to 80% of all stones in RYGB patients, implicating hyperoxaluria in the pathogenesis of urolithiasis. For this reason, calcium and vitamin D supplementation are routinely prescribed post-RYGB to reduce oxalate absorption from the gastrointestinal tract. However, patient compliance with these supplements remains unknown.

While several studies have examined urinary parameters postoperatively, few have assessed the incidence of stone formation post-RYGB.7–9 The first large scale study was conducted by Matlaga and colleagues. They examined urolithiasis within the first 4 years following RYGB surgery.4 Compared to obese patients not undergoing bariatric surgery, RYGB patients had a 1.7-fold risk of experiencing urolithiasis postoperatively.4 However, the time intervals at which RYGB patients develop kidney stones post-RYGB remain unknown. The incidence of 7.65% as determined by Matlaga and colleagues could be a considerable underestimation if a substantial portion of post-RYGB stone-formers experience urolithiasis past this 4-year time frame. Therefore, in this study we assessed the long-term incidence of symptomatic urolithiasis post-RYGB, the timing of post-RYGB symptomatic urolithiasis, and compliance of these patients with calcium and vitamin D supplementation.

Methods

Prior to the start of this study, approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of the McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) (#11-627-SDR). We contacted consecutive patients who had undergone RYGB between 1996 and 2011 at the MUHC (either laparoscopic or open) with 2 fellowship-trained bariatric surgeons (NVC, OC). All patients were contacted by telephone up to 3 times to complete a standardized telephone questionnaire (Appendix A). Since the MUHC is a tertiary bariatric referral centre, patients were referred from different regions for their bariatric surgery. Furthermore, patients changed residency during the postoperative period of 15 years. Out of the 1000 patients contacted, a total of 478 patients completed the telephone questionnaire, for a response rate of 48%. No patients were excluded from the study (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and descriptive variables

| Total no. patients | 478 |

|---|---|

| Time to follow-up (years) (mean ± SD) | 7.0 ± 4.2 |

| Male (%) : Female (%) | 25.7 : 74.3 |

| Age at RYGB surgery (years) (median; range) | 41 (18 – 70) |

| BMI before surgery (kg/m2) (median; range) | 51 (31–103) |

| Lowest BMI after surgery (kg/m2) (median; range) | 28 (17–67) |

| BMI at follow-up (kg/m2) (median; range) | 32 (17–69) |

| Smoking status (%): | |

| Current | 22.6 |

| Former | 29.9 |

| Never | 47.5 |

| Calcium supplementation (%) | 56.2 |

| Daily calcium dose (mg) (median; range) | 200 (0–3200) |

| Vitamin D supplementation (%) | 51.2 |

| Daily vitamin D dose (IU) (median; range) | 0 (0–20 000) |

SD: standard deviation; RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery; BMI: body mass index.

The telephone questionnaire assessed current health status, medical history and the use of medications that included calcium and vitamin D supplementation (Appendix A). For patients who developed symptomatic urolithiasis following RYGB, time to presentation with de novo or recurrence of symptomatic urolithiasis were recorded. Confirmation of stone disease using chart reviews or imaging studies was not possible since patients were not routinely screened or followed with imaging studies. Therefore, it was not possible to know for sure if they were stone-free at the time of RYGB.

Data were entered and analyzed with Statistical Package of Social Sciences version 17 (IBM Corporation, Armon, NY). Categorical variables were represented as frequencies and percentages. Associations between symptomatic urolithiasis and demographic variables or calcium and vitamin D supplementation were tested using Chi-square tests. Vitamin D and calcium doses were compared using one-way ANOVAs. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05 with two-tailed testing. Kaplan-Meier curves were generated using MedCalc version 12.7.7 (MedCalc Software, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

A total of 478 patients completed the telephone questionnaire with a mean follow-up of 7.0 years (range: 0–15) post-RYGB surgery (Table 1). Just over 56% and 51% of patients questioned were compliant with their calcium and vitamin D supplementation, respectively. Overall, 68 (14.2%) patients reported a history of symptomatic urolithiasis. Of these patients, 33 reported symptomatic stones only preoperatively, 25 presented with symptomatic stones de novo post-RYGB, and 10 patients had symptomatic stones both before and after RYGB surgery. Therefore, the rate of post-RYGB de novo symptomatic urolithiasis was 5%, and the rate of overall post-RYGB symptomatic urolithiasis was 7.3% with a median time to presentation of 3.1 years following RYGB surgery.

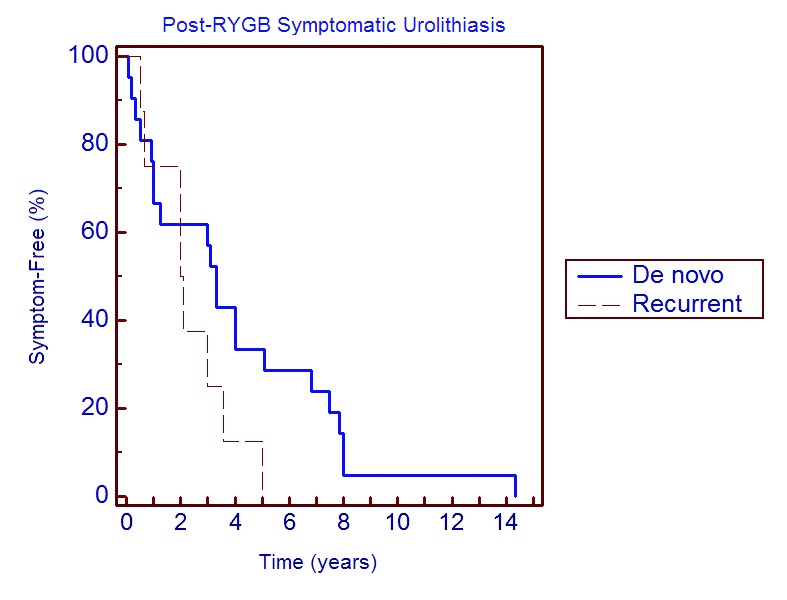

In de novo stone-formers, 33% of patients developed symptomatic urolithiasis within 1 year of surgery, 33% became symptomatic within 4 years, and the remaining 33% experienced symptomatic urolithiasis 4 to 14 years postoperatively (Fig. 1). Of the 10 patients who had recurrence of symptomatic urolithiasis post-RYGB, 88% presented in the first 4 years following surgery, compared with 66% in the de novo group. The median time to presentation with symptomatic urolithiasis in de novo stone-formers was 3.3 years versus 2.0 years in recurrent stone-formers (p = 0.38) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Kaplan-Meier curve plotting time to presentation with symptomatic urolithiasis in de novo and recurrent stone-formers post-RYGB.

To examine whether calcium and vitamin D supplementation had any preventative role in post-RYGB symptomatic urolithiasis, we compared all postoperative symptomatic stone-formers with patients who had no such prior history. Vitamin D and calcium supplementation, as well as their respective dosages, did not differ significantly between these 2 groups of patients (Table 2). Additionally, no statistically significant associations were found between supplementation and symptomatic urolithiasis when only de novo stone-formers were examined (Table 3). Of note, the mean follow-up time was significantly longer in de novo stone-formers, reaching 8.7 ± 3.7 years compared with 6.9 ± 4.2 years in those who had no prior history of symptomatic urolithiasis (p = 0.04).

Table 2.

Calcium and vitamin D supplementation in post-RYGB symptomatic stone-formers vs. non-stone-formers

| Symptomatic stone-formers | Non-stone-formers | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 35 | 410 | |

| Time to follow-up (years) (mean ± SD) | 7.9 ± 3.6 | 6.9 ± 4.2 | 0.17 |

| Male : Female | 9 (25.7%) : 26 (74.3 %) | 102 : 308 | 0.91 |

| Age at RYGB surgery (years) (median; range) | 42 (19–62) | 39 (18–67) | 0.39 |

| BMI before surgery (kg/m2) (median; range) | 52 (38–104) | 51 (35–98) | 0.37 |

| Lowest BMI after surgery (kg/m2) (median; range) | 29 (20–44) | 27 (17–67) | 0.27 |

| BMI at follow-up (kg/m2) (median; range) | 32 (20–49) | 32 (17–69) | 0.2 |

| Calcium supplementation | 20 (57.1%) | 223 (54.4%) | 0.73 |

| Daily calcium dose (mg) (median; range) | 200 (0–1500) | 0 (0–2283) | 0.98 |

| Vitamin D supplementation | 18 (51.4%) | 204 (49.9%) | 0.97 |

| Daily vitamin D dose (IU) (median; range) | 400 (0–2000) | 0 (0–20 000) | 0.11 |

SD: standard deviation; RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery; BMI: body mass index.

Table 3.

Calcium and vitamin D supplementation in de novo post-RYGB symptomatic stone-formers vs. non-stone-formers

| De novo symptomatic stone-formers | Non-stone-formers | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. patients | 25 | 410 | |

| Time to follow-up (years) (mean ± SD) | 8.7 ± 3.7 | 6.9 ± 4.2 | 0.04 |

| Male : Female | 6 (24%) : 19 (76%) | 102 (24.9%) : 308 (75.1%) | 0.92 |

| Age at RYGB surgery (years) (median; range) | 41 (19–61) | 39 (18–67) | 0.73 |

| BMI before surgery (kg/m2) (median; range) | 52 (40–73) | 51 (35–98) | 0.39 |

| Lowest BMI after surgery (kg/m2) (median; range) | 30 (22–44) | 27 (17–67) | 0.23 |

| BMI at follow-up (kg/m2) (median; range) | 33 (18–49) | 32 (17–69) | 0.22 |

| Calcium supplementation | 10 (40%) | 223 (55.8%) | 0.18 |

| Daily calcium dose (mg) (median; range) | 0 (0–1500) | 0 (0–2283) | 0.29 |

| Vitamin D supplementation | 12 (48%) | 204 (51.1%) | 0.76 |

| Daily vitamin D dose (IU) (median; range) | 0 (0–1000) | 0 (0–20 000) | 0.41 |

SD: standard deviation; RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery; BMI: body mass index.

Discussion

In accordance with studies that investigated both the incidence of urolithiasis and its risk factors, the incidence of symptomatic urolithiasis post-RYGB was 7.3% after a mean follow-up of 7.0 years. Interestingly, a third of de novo symptomatic stones were reported in the first year following surgery, while another third presented 4 to 14 years postoperatively. The median time to symptomatic stone presentation was 3.1 years. Compliance with calcium and vitamin D was 56 and 51%, respectively, without any significant associations between supplementation and symptomatic urolithiasis.

In this study, 7.3% of patients presented with symptomatic urolithiasis post-RYGB after a follow-up time that spanned 15 years. This is in concordance with the incidence rate of 7.65% reported by Matlaga and colleagues.4 These results demonstrate an increase in lifetime risk of stone formation when compared with the estimated prevalence of 5.2% in the general American population.10 Furthermore, the present study found that 5% of RYGB patients developed de novo symptomatic stones postoperatively. This is slightly higher than the 3.2% reported by Durani and colleagues over a shorter 7-year period.11 As the follow-up time in de novo stone-formers was significantly longer than in patients without any history of symptomatic urolithiasis (8.7 ± 3.7 vs. 6.9 ± 4.2 years; p = 0.04), the 5% rate of de novo symptomatic urolithiasis may be an underestimate. Since a third of de novo symptomatic stones presented beyond 4 years post-RYGB, these patients remain predisposed to kidney stone formation for many years following RYGB surgery.

Interestingly, a third of reported stones occurred in the first year following RYGB-surgery in both de novo and recurrent stone-formers. Although these patients claimed to have not been symptomatic at the time of surgery, the presence of occult stones cannot be ruled out without appropriate preoperative imaging studies. Small stones present at the time of bariatric surgery may have quickly grown in size secondary to the favourable conditions induced by increased oxalate absorption, decreased urine output, and sudden weight loss. The first year postoperatively, therefore, carries the highest risk of symptomatic urolithiasis for both recurrent and de novo stone-formers.

The mechanism of urolithiasis is believed to partially stem from the malabsorptive consequences of RYGB surgery. Due to a reduced capacity to absorb fat, calcium is saponified leaving oxalate unbound in the gastrointestinal tract. This leads to increased oxalate delivery to the colon where it is absorbed, while calcium is excreted along with the fat.12 As oxalate cannot be metabolized, these larger quantities of oxalate are cleared unaltered by the kidneys thereby increasing urinary concentrations. Indeed, 47% of RYGB patients manifest hyperoxaluria compared to just 10.5% in obese controls, predisposing this population to the development of calcium oxalate type stones.13

Calcium and vitamin D supplementation are routinely prescribed post-RYGB to prevent urolithiasis by decreasing oxalate absorption from the digestive tract. However, previous studies have shown that compliance with nutritional supplementation and vitamin D is only 33 and 27%, respectively.14,15 In the study presented, calcium and vitamin D compliance was appreciably higher than these previous estimates, and it remained comparable when patients were separated into de novo and recurrent stone-formers. Although compliance in this study was appreciably higher than previously described, it remains low. Improving compliance with calcium and vitamin D supplements in this population may help characterize their preventive role more accurately in future studies.

No associations, be they protective or predisposing, were found between calcium and/or vitamin D supplementation and symptomatic urolithiasis. Due to the self-reported nature of our data, inaccurate reporting by patients may have distorted an effect if one were present. Furthermore, low compliance may have further diluted any preventive role. Future studies would ideally be prospective in nature, improving accuracy in the calculation of stone incidence. These studies would also include measurements of urinary stone parameters to correlate supplementation with the development of urinary conditions that increase stone risk. In addition, imaging studies need to be performed prior to RYGB surgery to exclude patients who already have asymptomatic urolithiasis.

Several limitations to the current study should be mentioned. Firstly, data were predominantly collected via self-reporting; imaging studies or stone analyses were not available for corroboration. This raises the possibility of recall bias in recounting both supplement dosing regimens and episodes of symptomatic urolithiasis. Secondly, low compliance, irregular dosing and inappropriate timing of doses (e.g., between meals) may have masked any preventive effects conferred by calcium and vitamin D supplementation. Thirdly, roughly half of the total number of patients in this study could not be reached to complete the questionnaire, reducing the generalizability of the findings and possibly underestimating the incidence of symptomatic urolithiasis. Nevertheless, the present study is unique in that a large population of RYGB patients (n = 478) was contacted with a relatively long follow-up time spanning 15 years. This feature provided a rare and interesting window of time to assess the long-term risk of symptomatic urolithiasis post-RYGB.

Conclusion

A high postoperative incidence of symptomatic urolithiasis was found in a telephone survey of a large sample of post-RYGB patients. Interestingly, while a third of patients with de novo symptomatic urolithiasis presented during the first year following RYGB, another third presented between 4 and 14 years postoperatively. Compliance with routinely prescribed calcium and vitamin D supplementation was low and needs improvement. Clinicians need to be aware of these findings and account for the elevated and protracted risk of urolithiasis when caring for these patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Canadian Urological Association Scholarship Foundation and the Montreal General Hospital Foundation Awards to Sero Andonian.

Appendix A.

McGill University Health Centre Bariatric Questionnaire

| Name: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| RVH Unit No: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| Health Insurance No: (If contact details have changed) | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| Address: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |||

| ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | |||

| New phone numbers: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| E-mail address: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| Today’s Date: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ | ||

| Today’s Weight: | _______________________________ (kg or lbs) | ||

| Are you satisfied with your weight loss so far? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| Do you want to lose more weight? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| Since the surgery, have you used any weight loss products? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| If YES, please specify the products you used: _______________________________________________________________________________________ | |||

| Have you participated in any support group programs? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| If YES, how many sessions have you been to? _______________________________________________________________________________________ | |||

| Did you participate in the pre-operative information meetings? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| If YES, were these information sessions useful? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| Do you currently have a general practitioner who follows you regularly? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| Did you suffer from persistent vomiting in the first 12 weeks after your operation? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| Do you suffer from persistent vomiting now? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| The following best describes your diet: | |||

| __You eat what you want without any problem | |||

| __There are some foods that you can’t eat or tolerate | |||

| __There are many foods that you can’t eat or tolerate | |||

| __It is difficult to eat | |||

| __The whole situation involving eating is difficult | |||

For questions 1-6 use the VAS line 1 to 10:

| Compared to before your surgery, your appetite has actually: | |||||||||||

| Decr.: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10: Incr | |

| Presently, the quantity of meat you are eating is: | |||||||||||

| Low: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10: High | |

| Presently, the quantity of fruits and vegetables you are eating is: | |||||||||||

| Low: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10: High | |

| Presently, the quantity of sugar you are eating is: | |||||||||||

| Low: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10: High | |

| Presently, the quantity of soft drinks you are consuming is: | |||||||||||

| Low: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10: High | |

| Presently, the quantity of milk products you are consuming is: | |||||||||||

| Low: | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10: High | |

| Since this surgery for “obesity” have you been hospitalized? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| If YES specify main reason why for each time: | |||

| Acute gastric dilatation | ____ Esophagitis / Barrett’s Esophagus | ____ Protein or other nutritional deficiency | ___ |

| Acute renal failure | ____ Gallstones | ____ Psychosis | ___ |

| Anemia (late) | ____ Gastro-gastric fistula | ____ Pulmonary edema | ___ |

| Anastomosis / marginal ulcer | ____ GI bleeding | ____ Respiratory insufficiency | ___ |

| Band erosion | ____ Hair loss | ____ Severe Ileus | ___ |

| Bowel Obstruction | ____ Hepatic failure | ____ Severe protein deficiency or nutritional problems | ___ |

| Broken bones | ____ Kidney stones | ____ Spleen injury | ___ |

| Bulimia/Anorexia Nervosa | ____ Leak after GB | ____ Stomal outlet stenosis | ___ |

| CHF | ____ Myocardial infarction | ____ UTI | ___ |

| Cirrhosis | ____ New acid reflux giving you heartburn | ____ Vitamin, mineral deficiency | ___ |

| CVA | ____ Peptic/Gastric Ulcer | ____ Volvulus/Closed loop syndrome | ___ |

| Depression/Confusion after operation | ____ Persistent vomiting/nausea | ____ Wound infection (minor) | ___ |

| DVT | ____ Pneumonia | ____ Wound infection (major/causing dehiscence) | ___ |

| Did you require another bariatric surgery after your original obesity operation? | YES___ | NO___ | |

| If YES and you know the reason explain: ___________________________________________________________________________________________ | |||

Medication use Pre/Post Surgery:

| Now Taking | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking Pre-op | Less | Same | More | |

| Arthritis | ||||

| Blood Pressure | ||||

| Diabetes | ||||

| Heart | ||||

| High Lipids | ||||

| Calcium (dose/day) | ||||

| Vitamin D (dose/day) | ||||

Co-Morbidity outcome Pre/Post-op:

| Post-Op Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present Pre-Op | Worse | Same | Better | |

| Acid reflux | ||||

| Asthma | ||||

| Clots in the legs or the lungs | ||||

| Diabetes Mellitus (Type 2) | ||||

| Do your hips hurt? | ||||

| Do your knees hurt? | ||||

| Frequent colds | ||||

| Frequent ear infections | ||||

| Hay Fever | ||||

| Heart disease or heart attack | ||||

| High Blood Pressure | ||||

| High cholesterol/lipids | ||||

| Kidney Disease | ||||

| Kidney Stones | ||||

| Liver Disease (cirrhosis, NASH, etc) | ||||

| Low back, hip, knee, feet etc pain | ||||

| Skin irritation or dermatitis | ||||

| Sleep Apnea (with or without machine) | ||||

| Stomach Ulcers | ||||

| Stress incontinence | ||||

| Stroke | ||||

| Thyroid Disease | ||||

| Kidney stones: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Date Post-op: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Stone number: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Number of episodes: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Location of stone: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Side: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Size: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Treatment: | ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

Footnotes

This paper has been peer-reviewed.

Competing interests: Dr. Haddad, Dr. Scheffler, Dr. Elkoushy, Dr. Court, Dr. Christou, Dr. Andersen, and Dr. Andonian all declare no ompeting financial or personal interests.

References

- 1.Adams TD, Gress RE, Smith SC, et al. Long-term mortality after gastric bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:753–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson MK. Surgical treatment of obesity--weighing the facts. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:520–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0904837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matlaga BR, Shore AD, Magnuson T, et al. Effect of gastric bypass surgery on kidney stone disease. J Urol. 2009;181:2573–7. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen T, Godebu E, Horgan S, et al. The effect of restrictive bariatric surgery on urolithiasis. J Endourol. 2013;27:242–4. doi: 10.1089/end.2012.0408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Semins MJ, Asplin JR, Steele K, et al. The effect of restrictive bariatric surgery on urinary stone risk factors. Urology. 2010;76:826–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asplin JR, Coe FL. Hyperoxaluria in kidney stone formers treated with modern bariatric surgery. J Urol. 2007;177:565–9. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2006.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffey BG, Pedro RN, Makhlouf A, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is associated with early increased risk factors for development of calcium oxalate nephrolithiasis. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1145–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinha MK, Collazo-Clavell ML, Rule A, et al. Hyperoxaluric nephrolithiasis is a complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Kidney Int. 2007;72:100–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stamatelou KK, Francis ME, Jones CA, et al. Time trends in reported prevalence of kidney stones in the United States: 1976–1994. Kidney Int. 2003;63:1817–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Durrani O, Morrisroe S, Jackman S, et al. Analysis of stone disease in morbidly obese patients undergoing gastric bypass surgery. J Endourol. 2006;20:749–52. doi: 10.1089/end.2006.20.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mole DR, Tomson CR, Mortensen N, et al. Renal complications of jejuno-ileal bypass for obesity. QJM. 2001;94:69–77. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/94.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maalouf NM, Tondapu P, Guth ES, et al. Hypocitraturia and hyperoxaluria after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. J Urol. 2010;183:1026–30. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brolin RE, Gorman JH, Gorman RC, et al. Are vitamin B12 and folate deficiency clinically important after roux-en-Y gastric bypass? J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:436–42. doi: 10.1016/S1091-255X(98)80034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warde-Kamar J, Rogers M, Flancbaum L, et al. Calorie intake and meal patterns up to 4 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Obesity Surgery. 2004;14:1070–9. doi: 10.1381/0960892041975668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]