Abstract

Resistance to the first-line NRTIs, tenofovir and emtricitabine, does not generally confer resistance to zidovudine. The objective of this study was to describe the efficacy of zidovudine as modern day salvage antiretroviral therapy. This was a single-center, retrospective, observational, cohort study. Adult HIV-positive patients prescribed a zidovudine-containing regimen between 2005 and 2010 were identified from a computer database. All patients had failed at least one prior antiretroviral regimen before zidovudine. The primary outcome measure was virologic success at 24 weeks. Other efficacy and safety outcomes were determined, including virologic success at 48 and 96 weeks, CD4 count change from baseline, and incidence of adverse effects. Sixty-nine subjects were enrolled. The mean age was 43 years, 70% were male, and 85.5% were black. Most patients were highly antiretroviral experienced. At 24 weeks, 63.8% and 72.5% of patients achieved HIV RNA less than 50 and 400 c/mL, respectively. The median change in CD4 count from baseline to week 24 was +70 cells/mm3. The percent of patients who discontinued zidovudine due to adverse effects was 10%. In this highly treatment-experienced population, zidovudine as part of a salvage regimen appeared effective. Gastrointestinal adverse effects were reported, but zidovudine-associated metabolic effects were uncommon, suggesting zidovudine was generally well tolerated.

Introduction

Zidovudine, a nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI), was the first available drug for the treatment of HIV infection. Zidovudine is no longer recommended as first-line therapy because of its adverse effect profile, most notably metabolic complications such as lipoatrophy and lactic acidosis1,2 but also anemia. Metabolic adverse effects are closely linked to thymidine analogues, especially stavudine.3,4

Resistance to zidovudine is directed through a group of mutations known as thymidine analogue mutations (TAMS).5 As the use of NRTIs has shifted away from thymidine analogues, the pattern of resistance mutations has shifted away from TAMS. Instead, the reverse transcriptase mutations M184V and K65R are more often encountered.6 These mutations contribute to resistance to other NRTIs, including emtricitabine and tenofovir, the components of Truvada® (Gilead Sciences, Foster City, CA).7

Even with only the M184V mutation, it becomes difficult to design a fully active antiretroviral (ARV) regimen that includes two NRTIs. This mutation confers resistance to lamivudine and emtricitabine. Tenofovir and abacavir should not be used together because of intracellular antagonism.8 Didanosine and tenofovir should not be used together because they are both adenosine analogues, and the combination has been associated with a blunted CD4 recovery.9 The combination of didanosine and abacavir lacks clinical trial data, but antagonism with this combination is also possible.8 Stavudine-containing regimens are not ideal because of the aforementioned association with metabolic adverse effects. A regimen containing didanosine and stavudine is particularly problematic as these two NRTIs have additive toxicities leading to an unacceptably high risk of adverse effects.1,10 This reasoning leaves zidovudine and tenofovir as NRTI options in this clinical scenario. If the K65R mutation is also present, zidovudine becomes the only reliable NRTI option for inclusion in a salvage regimen.

Published research using zidovudine as a component of salvage therapy is limited. The objective of this study was to describe outcomes of zidovudine as part of a salvage antiretroviral regimen.

Methods

Study design

This was a single center, retrospective, observational, cohort study conducted in the infectious diseases clinic associated with Wake Forest Baptist Health, Winston-Salem, NC. Patients prescribed a zidovudine-containing regimen from January 2005 to December 2010 were identified from a computer database. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to determine study population. Medical records were retrospectively reviewed. The study was approved by the Wake Forest Baptist Health Institutional Review Board.

Patient population

HIV-positive patients greater than 18 years old were included who had failed at least one prior antiretroviral regimen before zidovudine initiation. Evidence of failing the prior regimen was documented. In general, this evidence involved two consecutive HIV RNA measurements greater than 1000 copies/mL while on therapy or a documented medication-related adverse effect. Patients were excluded because of resistance to zidovudine (defined as at least three TAMS, 69 insertion complex, or 151 complex),11 incomplete medical record, or if lost to follow-up before 24 weeks of therapy. Past medical history such as chronic kidney disease and hyperlipidemia were recorded if documented in the medical record.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was virologic success (HIV RNA less than 50 copies/mL) at 24 weeks. Secondary outcome measures included virologic success at 48 and 96 weeks and percent of patients with HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL at 24, 48, and 96 weeks. Reasons for failing the zidovudine-containing regimen were recorded, which included virologic failure, rebound, intolerance, resistance, and incomplete adherence, among others. Incomplete adherence was assumed if it was documented in the medical record. For the purposes of this study, published criteria for virologic failure were applied.1 Failures were carried forward for patients who were subsequently lost to follow-up. Additional analyses were performed to assess virologic response among patients with and without a history of incomplete adherence, change in CD4 count from baseline, virologic failure due to resistance, percent of patients who discontinued zidovudine due to adverse effects, and incidence of specific adverse effects associated with zidovudine.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to analyze baseline characteristics, and primary and secondary outcome measures.

Results

Patients

One hundred ninety-nine patients prescribed zidovudine were screened for enrollment; of these 69 met study criteria. Sixty-two patients did not have evidence of failing a prior regimen, and 13 were less than or equal to 18 years old. Forty were excluded because of incomplete medical record, 10 patients were lost to follow up, and 5 patients were excluded because of pre-existing zidovudine resistance. Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. Twenty (29%) patients had documented history of incomplete adherence.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Age, mean years±SD | 43.2±9.4 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 48 (70) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black | 59 (85.5) |

| White | 6 (8.7) |

| Hispanic | 4 (5.8) |

| Chronic hepatitis C, n (%) | 5 (7.2) |

| Chronic hepatitis B, n (%) | 7 (10.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease, n (%) | 14 (20.3) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (4.3) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 34 (49.3) |

| Hyperlipidemia, n (%) | 16 (23.2) |

| Baseline CD4 count, median (range) | 200 (8–1100) |

| Duration of prior ARV use, mean years±SD | 5.4±4.4 |

| Prior ARV regimens, mean number±SD | 3±2.6 |

| Prior ARV medications, mean number±SD | 5.7±2.8 |

| Prior ARV classes, mean number±SD | 2.5±0.6 |

| Regimen prior to zidovudine, n (%) | |

| NNRTI-based | 37 (53.6) |

| PI-based | 30 (43.5) |

| Raltegravir-based | 1 (1.4) |

| PI+raltegravir-based | 1 (1.4) |

ARV, antiretroviral; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitor.

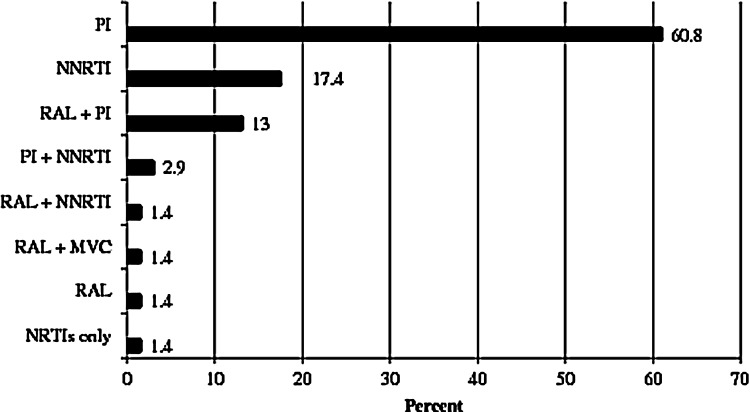

Zidovudine-containing regimens

The composition of zidovudine-containing regimens is shown in Fig. 1. The mean number of antiretrovirals prescribed was 3.5±0.6, ranging from three to five per regimen. Fifty-three (77%) patients received a boosted-protease inhibitor (PI) as part of their zidovudine-containing regimen. Of these, lopinavir/r (34%), atazanavir/r (25%), and darunavir/r (30%) were prescribed most often. Other prescribed protease inhibitors were nelfinavir (6%), unboosted-atazanavir (4%), and fosamprenavir (2%). Twelve (17%) patients received raltegravir, 75% of these with a boosted-PI. All but one of these received darunavir/r. Fifteen (22%) patients received a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) as part of their zidovudine-containing regimen; most received nevirapine (40%) and efavirenz (40%). Etravirine was prescribed in three (20%) of these patients, once with raltegravir and twice with darunavir/r. Other NRTIs were prescribed alongside zidovudine in 64 (92.8%) patients.

FIG. 1.

Composition* of zidovudine-containing regimens. *Antiretrovirals other than NRTIs. MVC, maraviroc; NNRTI, non-nucleotide inhibitor; PI, protease inhibitors; RAL, raltegravir.

Clinical outcomes

Virologic response rates are shown in Fig. 2. At 24 weeks, 44 (63.8%) patients achieved virologic success. At 48 and 96 weeks, 33 (50.8%) and 22 (38.6%) patients achieved virologic success, respectively. At 24, 48, and 96 weeks, 50 (72.5%), 38 (58.5%) and 26 (47.3%) patients achieved HIV RNA less than 400 c/mL, respectively. There was no appreciable difference in response rates of patients with or without a history of incomplete adherence (Fig. 3). Sixty-five percent of patients with a history of incomplete adherence achieved virologic success at 24 weeks compared with 63.3% of other patients. The median CD4 count at 24, 48, and 96 weeks was 285, 340, and 400 cells, respectively. The median change in CD4 count from baseline to 24, 48, and 96 weeks was +70, +80, and +125, respectively. A total of 15 (22%) patients failed their zidovudine-containing regimen at 24 weeks; the most common reason was virologic failure, which was cited for 66.7% of failed patients. Reasons for failing the zidovudine-containing regimen are listed in Table 2.

FIG. 2.

Virologic responses.

FIG. 3.

Virologic outcomes according to prior adherence.

Table 2.

Reasons for Failing Zidovudine-Containing Regimen at Week 24

| Reason citeda | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Virologic failure | 10 (14.5) |

| Adverse effect(s) | 7 (10.1) |

| Resistance | 5 (7.2) |

| Incomplete medication adherence | 5 (7.2) |

| Regimen change | 1 (1.4) |

| Total who failed regimen | 15 (21.7) |

Multiple reasons were possible.

Safety

The most commonly reported adverse effects were nausea and/or vomiting (10%) and diarrhea (12%). No patient experienced lactic acidosis or lipoatrophy, although one patient experienced new-onset diabetes and one patient experienced anemia.

Discussion

This study suggests zidovudine still has a role as salvage antiretroviral therapy. Available evidence to support this role is limited. Zidovudine has been evaluated as salvage therapy with tenofovir in the setting of a K65R mutation. One case series examined five patients who experienced virologic failure and had a K65R mutation but did not have TAMS. All patients described in this report achieved viral loads that were undetectable by 4 weeks of treatment and stayed virologically suppressed while on zidovudine.12

Likewise, virologic success was achieved in the majority of patients in this study. The number of patients who achieved virologic success decreased from 24 to 96 weeks; however, nearly 50% of patients maintained a HIV RNA less than 400 copies/mL at 96 weeks. Further supporting a positive effect is the increasing CD4 count, which rose by a median of 125 copies/mL by 96 weeks. This effect is considerable given the salvage nature of these treatments. Indeed, the patient population in this study had received an average of three prior regimens, making success with the zidovudine-containing regimen anything but certain.

The most common reason for failure in this study was virologic failure, present in 66.7% of those that failed. This might be expected for patients with a documented history of incomplete adherence. However, there was no difference between the groups based on prior adherence history. Accurately capturing this difference required appropriate documentation of incomplete adherence in the medical record. Inconsistencies in documentation may account for why a difference was not detected as all patients in this study had at least one risk factor for incomplete adherence (failing a prior regimen).

Our study is not without limitations. There was no comparator group, but this would have been challenging given the retrospective nature of the study and the heterogeneity that exists among salvage regimens. The retrospective design of the study also placed dependence on accurate documentation. It should be recognized that 20% of patients screened for this study were excluded because of an incomplete medical record. A common reason for this was lack of baseline laboratory data and/or medication history among patients transferring to the study site from a different clinic.

This study was performed at a single center in an industrialized country; therefore, applicability could be difficult, especially to resource poor settings where monitoring for potential anemia or metabolic complications may be less intense. That being said, the low-cost generic availability of zidovudine may justify its use as a salvage therapy in these settings. Many of these limitations are balanced by the real-world nature of this study. Success with a zidovudine-containing salvage regimen may be relatively lower if zidovudine is commonly employed as a first-line therapy, when the risk of underlying TAMS is greater among antiretroviral experienced patients. This may be important in resource-limited settings where resistance testing is not available to rule out presence of TAMS before initiating salvage therapy.

It is worth highlighting the potential impact of newer antiretrovirals, particularly boosted-protease inhibitors. Indeed, the advent of novel antiretrovirals has increased the number of salvage options available for antiretroviral experienced patients, including regimens that do not include a NRTI.13 Most patients (68%) in this study received zidovudine along with a boosted PI, while a smaller proportion received NNRTIs, raltegravir, or unboosted PIs. The only integrase inhibitor prescribed was raltegravir, owing to the time period of this study that preceded availability of elvitegravir and dolutegravir. Finally, regarding the safety of zidovudine, making conclusive associations between an adverse effect and a specific antiretroviral in the regimen was not always possible. For example, two of the most commonly reported side effects in the study were nausea and vomiting. These are potential side effects of zidovudine, but these are also potential side effects of other antiretrovirals, including PIs of which 77% of patients in the study were concurrently prescribed. While this study captures tolerability to a degree, length of follow-up may be insufficient to determine metabolic effects of zidovudine (e.g., lactic acidosis, lipoatrophy, and diabetes).

In conclusion, zidovudine appeared effective as part of a deep salvage antiretroviral regimen in this real-world study and was generally well tolerated with a low rate of adverse effects. It is best utilized in settings where adequate monitoring is available and where the prevalence of TAMS is relatively low among patients who fail initial therapies. Additional studies are warranted to evaluate the long-term safety of zidovudine when used as part of a modern day salvage regimen.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services. Available at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf (Last accessed April15, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Hoy JF, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection. 2012 Recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel. JAMA 2012;308:387–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arribas JR, Pozniak AL, Gallant JE, et al. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, emtricitabine, and efavirenz compared with zidovudine/lamivudine and efavirenz in treatment-naive patients: 144-week analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008;47:74–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bolhaar MG, Karstaedt AS. A high incidence of lactic acidosis and symptomatic hyperlactatemia in women receiving highly active antiretroviral therapy in Soweto, South Africa. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:254–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boucher CA, O'Sullivan E, Mulder JW, et al. Ordered appearance of zidovudine resistance mutations during treatment of 18 human immunodeficiency virus-positive subjects. J Infect Dis 1992;165:105–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paquet AC, Solberg OD, Napolitano LA, et al. A decade of HIV-1 drug resistance in the United States: Trends and characteristics in a large protease/reverse-transcriptase and co-receptor tropism database from 2003–2012. Antiviral Therapy 2014;19:435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truvada® [package insert]. Foster City, CA: Gilead Sciences, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perez-Olmeda M, Garcia-Perez J, Mateos E, et al. In vitro analysis of synergism and antagonism of different nucleoside/nucleotide analogue combinations on the inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Med Virol 2009;81:211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Negredo E, Bonjoch A, Paredes R, et al. Compromised immunologic recovery in treatment-experienced patients with HIV infection receiving both tenofovir disoproxil fumarate and didanosine in the TORO Studies. Clin Infect Dis 2005;41:901–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore RD, Wong WM, Keruly JC, et al. Incidence of neuropathy in HIV-infected patients on monotherapy versus those on combination therapy with didanosine, stavudine and hydroxyurea. AIDS 2000;14:273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson VA, Calvez V, Huldrych FG, et al. Update of the drug resistance mutations in HIV-1: March 2013. Topics Antiviral Med 2013;21:6–14 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephan C, Dauer B, Bickel M, et al. Intensification of a failing regimen with zidovudine may cause sustained virologic suppression in the presence of resensitising mutations including K65r. J Infect 2010;61:346–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tashima K, Smeaton L, Andrade A, et al. Omitting NRTI from ARV regimens is not inferior to adding NRTI in treatment-experienced HIV+ subjects failing a protease inhibitor regimen: The ACTG OPTIONS study. Program and abstracts of the 20th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, March3–6, 2013, Atlanta, Georgia. Abstract 153LB. [Google Scholar]