Abstract

Proangiogenic factors, vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) prime endothelial cells to respond to “hematopoietic” chemokines and cytokines by inducing/upregulating expression of the respective chemokine/cytokine receptors. Coculture of human endothelial colony forming cell (ECFC)–derived cells with human stromal cells in the presence of VEGF and FGF-2 for 14 days resulted in upregulation of the “hematopoietic” chemokine CXCL12 and its CXCR4 receptor by day 3 of coculture. Chronic exposure to the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 in this vasculo/angiogenesis assay significantly reduced vascular tubule formation, an observation recapitulated by delayed AMD3100 addition. While AMD3100 did not affect ECFC-derived cell proliferation, it did demonstrate a dual action. First, over the later stages of the 14-day cocultures, AMD3100 delayed tubule organization into maturing vessel networks, resulting in enhanced endothelial cell retraction and loss of complexity as defined by live cell imaging. Second, at earlier stages of cocultures, we observed that AMD3100 significantly inhibited the integration of exogenous ECFC-derived cells into established, but immature, vascular networks. Comparative proteome profiler array analyses of ECFC-derived cells treated with AMD3100 identified changes in expression of potential candidate molecules involved in adhesion and/or migration. Blocking antibodies to CD31, but not CD146 or CD166, reduced the ECFC-derived cell integration into these extant vascular networks. Thus, CXCL12 plays a key role not only in endothelial cell sensing and guidance, but also in promoting the integration of ECFC-derived cells into developing vascular networks.

Introduction

CXCR4, the G-coupled seven-transmembrane chemokine receptor, and its cognate ligand, CXCL12, are highly conserved in mammals and play key roles in a number of critical processes during normal embryonic development and postnatally [1,2]. These include hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell (HSC/HPC) trafficking, immune surveillance, blood vessel, cardiac and central nervous system formation during development, revascularization at sites of tissue injury, and the initiation and metastatic spread of tumors [1–9]. CXCL12 plasma levels are rapidly elevated in response to tissue damage, with increased CXCL12 concentrations correlating with the severity of injury, increased vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plasma levels, and the associated rapid mobilization of proangiogenic cells into the circulation [10,11].

Interactions of CXCR4 with CXCL12 can be inhibited by CXCR4 antagonists, which include the bicyclam AMD3100 [12,13], used therapeutically as an effective mobilizer of HSC/HPCs from bone marrow in patients refractory to G-CSF mobilization [12–15]. AMD3100 mobilizes human endothelial progenitor cells and proangiogenic cells into the peripheral blood in both the human and mice, although, in the murine studies, both endothelial and stromal progenitor cell mobilization was enhanced by VEGF pretreatment [16,17]. Interestingly, in the humans, more immature human endothelial progenitor cells or high proliferative potential–endothelial colony forming cells (HPP-ECFCs) are mobilized by AMD3100 than those with a lower proliferative potential [16]. Additionally, AMD3100 treatment can reduce blood vessel and tumor formation in preclinical models [18].

Blood vessel growth takes place by different mechanisms, which include vasculogenesis or de novo blood vessel formation from endothelial progenitor cells, angiogenesis (intussusceptive angiogenesis or sprouting of existing vessels), and arteriogenesis (the growth of collateral vessels in response to occlusion of major arteries and associated with endothelial and smooth muscle cell proliferation), and, during tumor growth, by vascular mimicry or blood vessel cooption [19–22]. For sprouting angiogenesis, the extracellular matrix surrounding the vasculature is degraded and mural cells detach from capillaries and microvessels (<100 μm in diameter) allowing the endothelial tip cells to become invasive and to form filopodia and lamellipodia in response to guidance cues, while stalk cells that lie behind the tip cells increase in number, extend the vessels, and form extracellular matrix, junctions, and lumens [19–22]. Once the tip cells anastomose or inosculate with other tip cells [23], vessel maturation takes place and this involves mural cell recruitment, extracellular matrix deposition, and the commencement of blood flow. A key feature of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis is central vascular lumen formation, the complexity of which has recently been reviewed [24–27]. The cord hollowing model of lumenization highlights the importance of interendothelial junctions and apicobasal polarity. Multicellular endothelial cell cords form, migrate into the stroma, lose apicobasal polarity and cord junctions, and increase to two or three cell thicknesses. Subsequently, endothelial cell repulsion, junctional rearrangements, and change in shape of endothelial cells result in unicellular tube formation [25–27].

Ex vivo assays have been developed to mimic human vessel formation either in fibrin or collagen gels [28–37]. These have combined endothelial cells or ECFCs with mural cells (eg, lung fibroblasts, dermal fibroblasts, retinal pericytes, or mesenchymal stromal cells) and specialized endothelial growth medium containing cytokines [eg, VEGF and fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2)]. These assays model endothelial cell migration toward each other to form endothelial cords, de novo lumen formation, angiogenic sprouting involving tip and stalk cells, and perivascular cell stabilization of vessels. They have significant advantages over the commonly employed matrigel assay [38] because the influence of both specific cellular and extracellular matrix components of the vascular niche can be studied as human ECFC-derived cells form and integrate into developing vascular networks. They are also amenable to pharmacological and/or molecular manipulation, may be used for immunofluorescent labeling studies, and are ideal for live cell imaging of vessel development using fluorescently labeled cell populations. Using one of these assays, VEGF and FGF-2 were found to upregulate the “hematopoietic receptors” CXCR4, c-kit, CSFR1, Flt3R, and IL-3Rα on endothelial cells, thereby priming these cells to respond to their respective ligands—CXCL12, SCF, M-CSF, Flt3-ligand, and IL-3—and promoting vascular tube maturation and sprouting [39].

We have adapted our version of these in vitro models, in which human umbilical cord blood (CB) or umbilical cord (UC) ECFC-derived cells are cocultured with human dermal fibroblasts (hDFs) or human bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells (hBM MSCs) in a 3D collagen type I sandwich assay in media containing VEGF and FGF-2 [34–37], by further developing a method to assess integration of exogenous human ECFC-derived cells into immature vascular tubule networks. Here, using this model together with time-lapse microscopy and fluorescently tagged cells, we analyzed the effects of the AMD3100 antagonist on human vasculogenesis and angiogenesis and showed that AMD3100 not only inhibits the dynamic refinement of the vascular network in vitro by enhancing endothelial cell retraction but also modulates the incorporation of ECFC-derived cells into extant vascular networks.

Materials and Methods

Cells and lentiviral transduction

Human umbilical CB units and UCs were collected with informed written consent from the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford with ethical approval for collection from the Oxford Research Ethics Committee and used in these studies with ethical approval from the Berkshire Research Ethics Committee and with approval of the NHSBT R&D institutional review committee. ECFC-derived cells from CB and human umbilical vein were prepared and cultured in complete EGM2 medium [35–38]. hDFs, human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), and hBM MSCs were also sourced from Lonza Biologics and cultured as described [35–38]. Typical immunophenotypes of these CB and HUVEC ECFC-derived cells and hBM MSCs have been described previously [35–38] and in Supplementary Fig. S1 (Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/scd). Early passage (p1–2) CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs or hDFs were transduced with eGFP or DsRed lentiviral vectors, respectively, as described in “Supplementary Materials and Methods” section and Supplementary Fig. S2 [35].

Vascular tubule assays, AMD3100 treatment, and immunofluorescence labeling

For the tubule assay, hDFs (unlabeled or transduced with DsRed) or unlabeled hBM MSCs were cocultured with either CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs (unlabeled or tranduced with eGFP) in complete EGM2 medium containing VEGF and FGF-2 for up to 14 days [35–37]. For a standard assay, 1.5×103 CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs were cocultured with 1×104 hDFs or BM MSCs per well of a 48-well plate in triplicate wells in EGM2 media (Lonza Biologics). Media were changed every 3–4 days for the duration of the assay as indicated. Quantification of the resulting tubules was performed by dividing each well into quarters and photographing eGFP-expressing tubules or CD31-labeled tubules [34–36] in each quarter at 4× magnification on a Nikon Inverted TE300 microscope (Nikon UK Ltd.) fitted with a cooled CCD camera and IPLab v3.61 imaging software (Scanalytics; BD Biosciences). Images were processed in Adobe Photoshop 7 and tubule numbers, lengths, and number of junctions were quantified using Angiosys software (TCS Cellworks). Media with or without AMD3100 (0–5 μM; Sigma-Aldrich Ltd.) added from the start of or during the coculture period were changed every 3–4 days for the duration of the assay and tubules were quantitated and stained with CD31 antibody as described [34]. Briefly, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 70% (v/v) ice-cold ethanol or 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) and unlabeled CB ECFC-derived cell or HUVEC cultures were washed with PBS containing 1% (w/v) bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) and stained for 1 h at room temperature with mouse anti-human CD31 (clone WM59, mIgG1; AbD Serotec) followed by washing three times with PBS-BSA then staining with alkaline phosphatase conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG1 secondary antibody (Serotec) and counterstaining with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitro blue tetrazolium (Sigma Aldrich Ltd.). Tubule assays using eGFP-labeled HUVECs or CB ECFC-derived cells and unlabeled hDFs or hBM MSCs were set up on coverslips in or directly on 24-well plates. At indicated time points and where relevant, tubule assays were fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA and, where indicated, cells were permeabilized with 0.25% (w/v) Triton X-100. Immunolabeling was performed with the following primary antibodies: CD31 (clone WM59; AbD Serotec), CXCR4 (1:25, 12G5; BD Biosciences), and CXCL12 (1:1,000, clone 79018; R&D Systems), followed by Alexa-555 goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (1:800; Invitrogen Ltd.), or with affinity purified rabbit anti-CXCR4 polyclonal antibody (ab2074; Abcam Ltd.) followed by Alexa-555 goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen Ltd.). Cells were imaged using an E600 microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera and Axiovision software (Nikon UK Ltd.).

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

The concentration of CXCL12 (SDF-1α) in the cell lysates was measured as indicated in the “Results” section using a specific ELISA kit (DSA00; R&D Systems). Culture supernatants were used unconcentrated or concentrated 10-fold with Amicon Ultra 0.5-mL centrifugal filters (Millipore Ltd.). Cultured cells were washed with PBS, lysed in lysis buffer comprising 1% (w/v) IPEGAL, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 137 nm NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, and ×1 protease inhibitors (all from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd.) for 30 min at 4°C and the resulting lysates were centrifuged at 140 g for 5 min before the resulting supernatant was collected, tested for protein content [34], and frozen in aliquots at −80°C. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was carried out according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, supernatants, cell lysates, and recombinant SDF-1α standards (0 to 10,000 pg/mL) were used undiluted or diluted in the RD6Q diluent or lysis buffer previously described and added to 100 μL of assay diluent-55 in 96-well plates—the latter four reagents being from the ELISA kits, Proteome Profiler Array kit (R&D Systems), or Sigma Aldrich Ltd. After incubation for 2 h at room temperature on a horizontal shaker (200±50 rpm), the wells were washed four times with 200 μL wash buffer and an horseradish peroxidase (HRP)–conjugated polyclonal antibody to SDF-1α was added for 2 h at room temperature on the horizontal shaker, the wells were washed as described earlier, and the reaction was developed using 200 μL per well of substrate solution (reagent A: stabilized hydrogen peroxide; reagent B: stabilized chromogen and tetramethylbenzidine) for 30 min at room temperature protected from light and stopped with 50 μL of 2 N sulfuric acid. The optical density was read using a BioRad 680 microplate reader (BioRad Laboratories, Inc.) at 450 nm.

Cell proliferation assays

Vascular tubule assays were established in 24-well plates using 3×103 eGFP-transduced HUVECs or CB ECFC-derived cells and 2×104 hDFs per well. For endothelial and hDF proliferation, cells were exposed to 0, 1, or 5 μM AMD3100 and eGFP-positive endothelial cells (HUVECs and CB) or unlabeled hDFs counted after trypsinization at days 4 and 7 using a hemocytometer. Single-cell ECFC assays were performed in a similar manner to those described [34,40] as described in the “Supplementary Materials and Methods” section.

Time-lapse live cell imaging

Time-lapse live cell imaging was established over the 14 days of vascular tubule formation. To image the effects of AMD3100 on vascular tubule maturation and more specifically on the extension and retraction of endothelial cells from the tubule network, tubule assays were established and images were taken at day 9 of the assay. Subsequently, AMD3100 was added to assigned wells and images were taken over the next 5 days to generate tubule maturation (Supplementary Movies) in the presence or absence of AMD3100. In each experiment, three or four Supplementary Movies were collected for each condition. Tubule changes during maturation in the presence or absence of drug were determined by (1) assessing the complexity of the tubule network (tubule numbers, lengths, and number of junctions) at day 9 and again at day 14 using the Angiosys software and (2) by assessing the behavior of individual tubule ends in a Supplementary Movie over the time course of the maturation experiments. This was achieved by tracing the tubule network at time zero (day 9) and again at 120 h (day 14) and scoring each tubule end as stabilized, extended, or retracted. The probability of tubule retraction was the number of retracted tubule ends, expressed as a proportion of total tubule ends for each movie (n=4 for each condition).

Integration assay

The integration of exogenously added eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs into a developing HUVEC-hDF or HUVEC-hBM MSC tubule network was assessed using a novel assay. Unlabeled HUVECs and hDFs or hBM MSCs were first cocultured in complete EGM2 medium containing VEGF and FGF-2 for 6 days to establish an immature tubule network [35] and media were replaced with 200 μL of complete EGM2 media with or without 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 for 1 h at 37°C. Separately, but simultaneously, eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs were trypsinized and incubated with complete EGM2 medium, with or without 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 for 1 h at 37°C, and treated cells in 200 μL medium were added to individual tubule coculture wells in triplicate. After 48 h in the presence or absence of AMD3100, tubules were fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA and immunolabeled with CD31 antibody as described previously and by Zhang et al. [34] and the number of eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs that were either fully incorporated into the tubule network (integrated cells) or excluded (nonintegrated cells) from the network were counted and the ratio of integrated and nonintegrated cells was calculated. Total tubule numbers over this period of time were assessed using the same protocol with or without AMD3100 and as described previously.

Proteome profiler arrays and antibody blockade

HUVECs or CB ECFC-derived cells cultured in complete EGM2 medium containing VEGF and FGF-2 overnight at 37°C were analyzed by flow cytometry for CXCR4 expression and tubule formation (Supplementary Data). The cells at ∼80% confluency were transferred to EBM2 medium with 0.5% (v/v) fetal calf serum (FCS; PAA Laboratories) containing 150 ng/mL CXCL12 (Peprotech EC Ltd.) or 5 μM AMD3100 or left untreated for 24 h at 37°C before lysis in 1% (w/v) IPEGAL, 20 mM Tris-HCl, 137 nm NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, and 1× protease inhibitors (all from Sigma-Aldrich Ltd.) for 30 min at 4°C. Lysates were centrifuged at 140 g for 5 min and the lysate supernatant was frozen in aliquots at −80°C. The Proteome Profiler Human Soluble Receptor Array Kit Non-Hematopoietic Panel comprising the Non-Hematopoietic and the Common Analyte arrays (R&D Systems) were used to analyze molecular changes in these cell lysates following CXCL12 or AMD3100 treatments or without treatment and according to the manufacturer's instructions as described [35,36]. Based on the method used for quantification, either the HRP-conjugated streptavidin provided in the kit or IRDye® 800CW streptavidin was used. Visualization and quantitation of the detected spots were performed using one of two methods. The first involved the use of Quantity One Software 4.4.1 (BioRad Laboratories, Inc.). The second used the LI-COR Odyssey scanner and Odyssey 3.0 analytical software (LI-COR Biosciences). Two different batches of HUVECs treated with either AMD3100 or CXCL12 or left untreated for 24 h were tested, with each totaling four replicate dotblots. Dotblot pixel density values were corrected by normalizing each dotblot to the highest average control and subtracting the average pixel density values of negative control dotblots in each blot.

To analyze the effects of antibody blockade on the integration of exogenously added eGFP-labeled HUVECs, unlabeled HUVECs and hBM MSCs were first cocultured in EGM2 medium as described previously for 6 days to establish an immature tubule network. At day 5, eGFP-labeled HUVECs also cultured in EGM2 medium containing VEGF and FGF-2 were treated with 150 ng/mL CXCL12 or 5 μm AMD3100 in EBM2 media containing 0.5% (v/v) FCS for 24 h. At day 6 of coculture, the media in wells were replaced with 200 μL of neutralizing mouse anti-human CD146 [5 μg/mL, clone F4-35H7 (S-Endo1); Stago Biocytex], mouse anti-human CD31 (80 μg/mL, clone WM59; Biolegend), and mouse anti-human CD166/ALCAM (60 μg/mL, clone 105901; R&D Systems) antibodies or equivalent mIgG1 isotype controls for 1 h at 37°C. Separately, but simultaneously, eGFP-labeled HUVECs were briefly trypsinized and then incubated with 200 μL of these neutralizing antibodies for 1 h at 37°C, before 800-treated eGFP-labeled HUVECs in 200 μL EGM2 medium were added to individual tubule coculture wells in triplicate. After 48 h, cells were washed and tubules were fixed in 4% (w/v) PFA and immunolabeled as relevant with either CD31 or CD146 antibodies (clones WM59, Biolegend, and OJ79c, Serotec, respectively) followed by Alexa-555-conjugated secondary antibodies [34]. For each well, the number of eGFP-labeled HUVECs that were either fully incorporated (integrated/sprouting cells) or nonintegrated into the tubule network were counted and the ratio of integrated to nonintegrated cells was calculated. Where more than one overlapping eGFP+ cell was observed at a single integration site in the tubule network, this was scored as one integration event, whereas separated green cells were scored as independent integration events.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±SEM and statistical analyses were performed using a one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests or unpaired Student's two-tailed t-tests using STATISTICA software v.10 (2011; StatSoft) as indicated. Statistical differences of P<0.05 were considered significant. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean in all cases.

Results

CXCR4 and CXCL12 are dynamically expressed during tubule formation

We used our in vitro sandwich model to assess and manipulate multiple stages of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis over 14 days. This involved coculturing stromal cells, hDFs, or hBM MSCs with either CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs in complete EGM2 medium that contained both VEGF and FGF-2. During this assay, ECFC-derived cells form multicellular structures in the first 2–3 days and then migrate into thread-like tubule structures over the first week of coculture, and, by 12–14 days, mature to form a network of anastomosing vessels (Fig. 1A) and as previously described [34–37]. Transducing CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs with an eGFP-expressing lentiviral vector allowed live cell imaging of vessel formation. In Supplementary Movies S1 and S2, the formation of a tubule network that undergoes dynamic reshaping over the time course of the assay via tubule extensions, retractions, and stabilizations was observed.

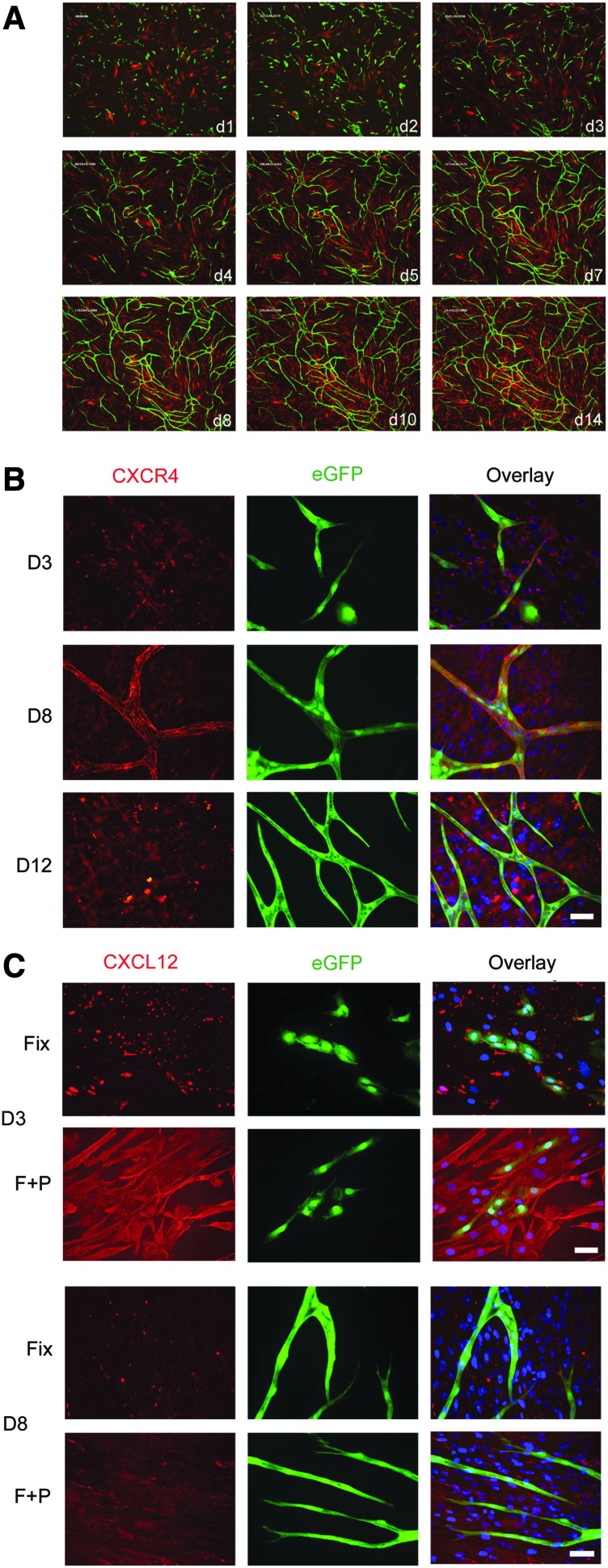

FIG. 1.

CXCR4 and CXCL12 localization during tubule development. (A) Vascular tubule development in a microenvironmental niche in vitro using eGFP-transduced CB ECFC-derived cells and DsRed-transduced hDFs. Individual images were taken from Supplementary Movie S1 at the days indicated (4× magnification). (B) CXCR4 immunolabeling (red) using the 12G5 monoclonal antibody on fixed eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells at days 3, 8, and 12 of the vascular tubule coculture assay. Overlay images show CXCR4, eGFP, and DAPI labeling. (C) CXCL12 immunolabeling (red) on fixed (Fix) and fixed and permeabilized (F+P) vascular tubule assays at days 3 and 8. Overlay images show CXCL12, eGFP, and DAPI labeling. Note that the stainings shown here were performed at the same time with the same dilution of antibody and images across time points were taken with the same exposure settings. Scale bar=50 μm. CB, cord blood; ECFC, endothelial colony forming cell; hDF, human dermal fibroblast.

One practical advantage of this tubule assay is that it is amenable to immunostaining experiments. Since CXCR4 has been reported to be upregulated on endothelial cells by VEGF and FGF-2 [39] and as both these factors were present throughout our coculture assay, we examined the expression of CXCR4 and its chemokine ligand, CXCL12, over time in the cocultured cells. Prior to coculture, CXCR4 surface expression levels were detected with the 12G5 or anti-CXCR4 polyclonal antibody (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4). At day 3 of the coculture assay, PFA-fixed CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs showed variable punctuate CXCR4 surface labeling with the 12G5 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. S5a). In these cocultures, the hDFs or hBM MSCs also demonstrated punctuate CXCR4 labeling (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Figs. S5a and S6). By day 8, when an immature tubule network had formed, there was prominent surface labeling of the endothelial cells, and the tubules resembled a patchwork of CXCR4 staining (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Figs. S5a and S6). Filopodia emerging from developing tubules also labeled strongly (Supplementary Fig. S5a). Similar staining was seen on both CB ECFC-derived cell– and HUVEC– (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Figs. S5a and S6) derived tubules. At day 12, CXCR4 labeling of endothelial cells as assessed with 12G5 antibody was also positive. CXCL12 labeling of fixed eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cell or HUVEC cultures at day 3 showed intense clusters of immobilized CXCL12 associated with both endothelial cell types (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. S5b, respectively). Fixed and permeabilized cultures demonstrated strong intracellular labeling of both endothelial cells and hDFs. At day 8, the clustered CXCL12 as well as the intracellular labeling was present in the cocultured cells. Similar CXCL12 labeling was seen at day 12. In some cocultures, such as those illustrated in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. S5b, there appeared to be less CXCL12 staining at day 8 than at day 3. We therefore quantified the CXCL12 (SDF-1α) concentrations in the day -3 and -8 coculture lysates by ELISA using three batches of HUVECs or CB ECFC-derived cells and a single batch of hDFs or hBM MSCs. While a decrease in CXCL12 (SDF-1α) levels was observed at coculture day 8 compared with day 3 for two of the three cell lysates tested when hBM MSCs were cocultured with three different batches of CB ECFC-derived cells, on average the CXCL12 (SDF-1α) levels were not statistically different (392±167 pg/mg protein, range=222–725 pg/mg, at day 3 vs. 460±119 pg/mg protein, range=222–583, at day 8; P=0.76 Student's t-test). There was also no significant difference in CXCL12 (SDF-1α) levels when hBM MSCs were cocultured with three different batches of HUVECs (307±20 pg/mg protein, range=274–344, at day 3 vs. 432±65 pg/mg protein, range=327–552, at day 8; P=0.14 Student's t-test). The concentrations of CXCL12 (SDF-1α) were lower when the same CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs were cocultured with hDFs for 3 days (171±15 pg/mg and 214±28 pg/mg protein, respectively) when compared with coculturing with hBM MSCs. However, in the experiments presented here for day-8 cocultures, these had reached similar levels irrespective of whether the cocultures contained hDFs or hBM MSCs (523±42 pg/mg protein vs. 435±35 pg/mg protein for day-8 hDF cocultures with CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs, respectively). For these latter cocultures, there was on average significantly more CXCL12 (SDF-1α) detected at day 8 than at day 3 when CB ECFC-derived cells, but not HUVECs, were cocultured with hDFs (P=0.001 and P=0.08, respectively; Student's t-test). Thus, CXCR4 and its ligand CXCL12 are dynamically coexpressed during tubule formation and maturation in this assay in the presence of VEGF and FGF-2.

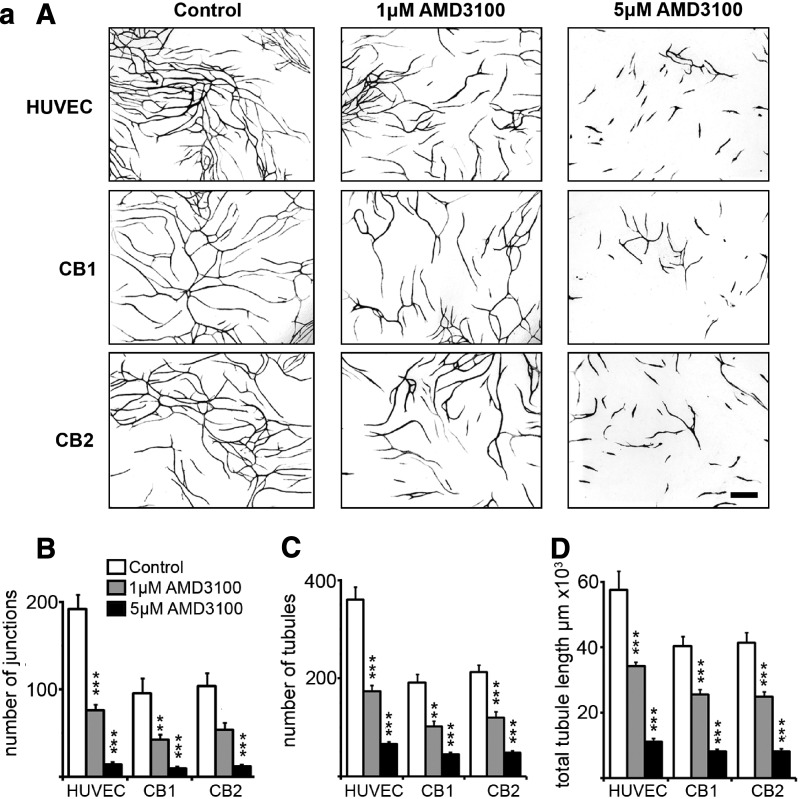

Chronic exposure to AMD3100 inhibits tubule development

To investigate the effects of AMD3100 on tubule development, assays using eGFP-transduced human CB ECFC-derived cells or HUVECs together with nontranduced hDFs or hBM MSCs were performed over 14 days in the continued presence of 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. S7). AMD3100 treatment profoundly affected both CB ECFC-derived cell and HUVEC tubule development in the presence of stromal cells with a significant reduction in the number of tubule junctions, and total tubule numbers and length when compared with untreated cells (B–D in Fig. 2a, ***P<0.001 or **P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=11–12 for each condition). Treatment with 5 μM AMD3100 generated significantly shorter tubules than 1 μM in all cases (P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=11–12). These results support the conclusions that AMD3100 treatment inhibits the formation of new blood vessels in this human coculture vascular tubule assay.

FIG. 2.

Chronic and delayed addition of AMD3100 affects CB ECFC-derived cell and HUVEC tubule formation. (a) Chronic AMD3100 exposure: (A) Representative fields of resulting vascular tubules after 14 days in culture exposed to control conditions (no drug), 1, or 5 μM AMD3100. One batch of eGFP-labeled HUVECs and two different batches of eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells (CB1 and CB2) were used with hDFs. Scale bar=400 μm. (B–D) Quantification of vascular tubule phenotypes at day 14 resulting from exposure to AMD3100. For each batch of ECFC-derived cells tested, there is a significant reduction in the number of junctions (A), tubules (B), and total tubule length (C) on exposure to 1 and 5 μM AMD3100 compared with control conditions, **P<0.01 or ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=11–12 for each condition). (b) Delayed addition of AMD3100: (A) Representative fields of vascular tubules at day 14 after the addition of 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 at days 0, 4, 6, 8, and 10 of culture. Once AMD3100 was added, cultures were continually exposed to the drug by changing the media and adding fresh drug every 2–3 days until day 14 when vascular tubules were fixed and photographed for eGFP expression and tubule complexity was quantified. Scale bar=400 μm. (B) Quantification of vascular tubule phenotypes. Chronic exposure (from day 0) to either 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 affected network development as demonstrated by a significant reduction in the number of junctions, tubules, and total tubule length (***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=11–20; ns=not significant). Addition of 1 μM AMD3100 to the developing tubules after 4, 6, or 8 days in culture generated day-14 vascular tubule phenotypes that were significantly different from the control (***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=7–20) but not significantly different to those obtained on chronic exposure to the drug [day 0, P=0.41 (junctions), P=0.36 (number of tubules), P=0.57 (total tubule length) one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=7–11]. Addition of 5 μM AMD3100 to tubules at days 4, 6, 8, and 10 generated day-14 vascular tubule phenotypes that were significantly different from both the control (*P<0.05, **P<0.01, or ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=7–20) and tubules chronically exposed to the drug (#P<0.05 or ###P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=7–12). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. HUVECs, human umbilical cord vein endothelial cells.

Delayed addition of AMD3100 affects vascular tubule formation

To further explore the effects of AMD3100 during tubule organization and vessel maturation, tubule coculture assays were initiated with HUVECs and hDFs and 1 or 5 μM of AMD3100 was added to the culture medium after 0, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days. Once AMD3100 was added, cultures were continually exposed to the drug until day 14 when tubules were fixed, photographed for eGFP expression, and quantified. We noted that while the general trend of the tubule phenotypes generated by AMD3100 treatment was consistent across experiments, the precise numbers of tubules produced and the extent to which AMD3100 inhibited tubule development varied slightly with cell batches. As expected, chronic exposure (from day 0) to either 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 significantly affected network development (***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=11–20; Fig. 2b). Interestingly, the addition of 1 μM AMD3100 to the developing tubules after 4, 6, or 8 days in culture generated tubule phenotypes at day 14 that were significantly different from the untreated control (***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=7–20). However, there was no significant difference between tubule phenotypes observed at day 14 upon chronic exposure to 1 μM AMD3100 (from day 0) and those obtained on addition of the drug after 4, 6, or 8 days in culture [P=0.41 (junctions), P=0.36 (number of tubules), P=0.57 (total tubule length) one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=7–11]. This suggests that 1 μM AMD3100 treatment most likely affects later stages of tubule organization and maturation rather than the initial stages. The delayed addition of 5 μM AMD3100 after 4, 6, 8, or 10 days in coculture generated tubules at day 14 that were significantly different from the untreated control (***P<0.001, **P<0.01, or *P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=7–20) and were reminiscent of the inhibition of tubule formation with 1 μM AMD3100 between days 4 and 8 (Fig. 2b). However, chronic exposure to 5 μM AMD3100 from day 0 gave significantly more inhibition than the delayed exposure (###P<0.001 or #P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests in all cases, n=7–12). This implies that higher concentrations of AMD3100 have additional effects at early stages of tubule development. Indeed, it was noted that chronic treatment with 5 μM AMD3100 generated tubules by day 14 of culture that were significantly reduced compared with 1 μM treatment (P<0.002, paired Student's two-tailed t-test, n=11). The following experiments were therefore designed to assess the action of AMD3100 on the proliferation, organization, and maturation of ECFC-derived cells (CB or HUVECs) during vascular tubule formation.

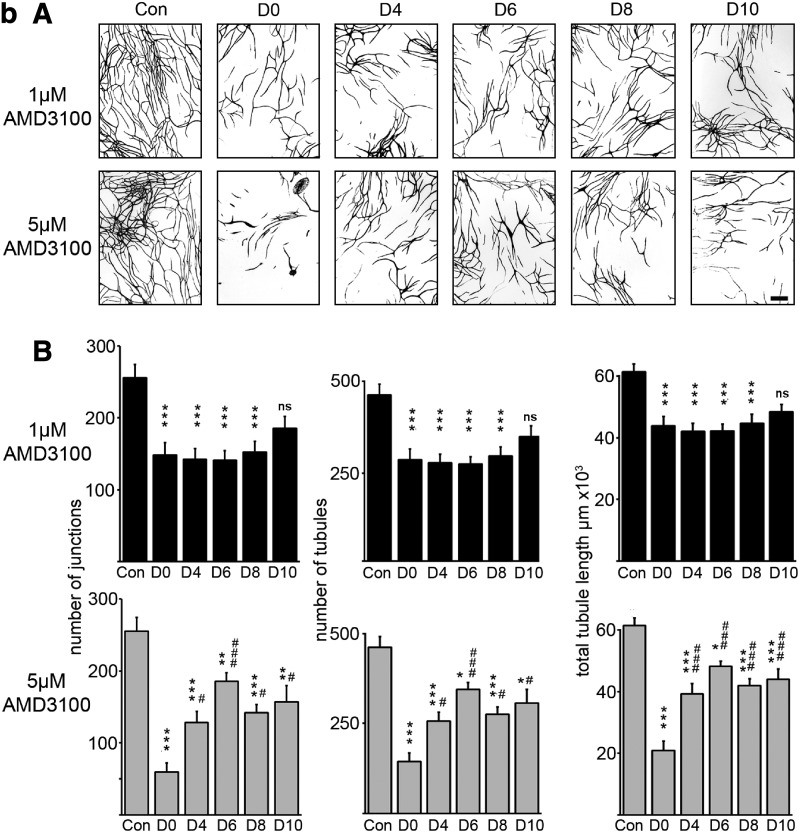

Endothelial cell retraction is enhanced with AMD3100

To examine the effects of AMD3100 during maturation on the tubule network, we used time-lapse live cell imaging of eGFP-transduced ECFC-derived cells to generate short Supplementary Movies of established tubule networks exposed to AMD3100. Images of the tubule network were taken at day 9, prior to the addition of AMD3100, and subsequent images were collected over the following 5 days. The Supplementary Movies were first quantified by comparing the number of junctions and tubules, and total tubule length for the network at day 9 before drug treatment began, and at day 14 at the end of the experiment. Figure 3A shows the relative change in each tubule parameter normalized to control values. Exposure to either 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 resulted in a statistically significant decrease in junctions, tubule number, and total tubule length (Fig. 3A: ***P<0.001 or **P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=10 separate Supplementary Movies for Control and 1 μM AMD3100, and n=12 for 5 μM AMD3100, over three experiments). This supported earlier observations in Fig. 2b that AMD3100 treatment affects the final day-14 tubule phenotype when added at days 9–10 until day 14 of the assay.

FIG. 3.

AMD3100 treatment affects the maturation of tubule networks and promotes tubule retraction. (A) Graph showing the relative change in number of junctions, number of tubules, and total tubule length normalized to control values in the presence or absence of AMD3100 between days 9 and 14 of the assay. Exposure to either 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 resulted in a statistically significant decrease in these parameters [**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=10 separate Supplementary Movies (Control and 1 μM AMD3100) or n=12 (5 μM AMD3100) over three experiments]. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. (B) AMD3100 treatment promotes vascular tubule retraction. Four control Supplementary Movies and four Supplementary Movies collected from vascular tubules exposed to either 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 were analyzed. Each tubule tip was scored for its behavior (stabilized, extended, or retracted) between day 9 (0 h) and day 14 (120 h). (C) Graph showing the probability of tubule retraction under control conditions or exposure to AMD3100 between days 9 and 14. There is a significant increase in the probability of tubule retraction in the presence of 5 μM AMD3100 compared with control (*P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=4). ns, not significant. hDFs were used as mural cells in these experiments.

To further investigate how AMD3100 affects the state of the tubule network, we used our time-lapse imaging experiments to track the behavior of individual tubules from control Supplementary Movies and from Supplementary Movies of networks exposed to 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 (n=4 in each case, as exemplified in Supplementary Movies S3–S5). These analyses revealed that under control conditions, even when the network exhibits no net growth between days 9 and 14, individual tubular cells reminiscent of tip-like cells are dynamically extending and retracting (Supplementary Movie S3). Each tubule was scored for its behavior (stabilized, extended, or retracted). Figure 3B classifies the behavior of all tubule ends (retracted, stabilized, or extended) in the presence and absence of AMD3100 and suggests a dose-dependent increase in the proportion of retracted tubules. Indeed, Fig. 3C demonstrates a significant increase in the probability of tubule retraction in the presence of 5 μM AMD3100 (*P<0.05, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=4).

AMD3100 treatment does not affect the proliferative or clonogenic potential of HUVECs and CB ECFC-derived cells

We next used the clonogenic single-cell ECFC assay to specifically examine whether AMD3100 affected the proliferation of clonogenic cells in the CB ECFC-derived cell and HUVEC cultures in the absence of stromal cells, but in the presence of VEGF and FGF-2. Using eGFP-transduced CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs, single cells were plated into individual wells of 96-well plates. After 14 days, the number of cells in each well was estimated and assigned to the following categories: single cell, cell cluster (<50 cells), low proliferative potential ECFCs (LPP-ECFCs, 50 to <2000 cells), and HPP-ECFCs (≥2000 cells). Figure 4A demonstrates that AMD3100 (0, 1, and 5 μM) did not inhibit the proliferative potential of these cells to form clusters or colonies [P=0.35 (clusters), P=0.87 (LPP-ECFCs), and P=0.26 (HPP-ECFCs), one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=3 experiments]. The survival of these cells was also unaffected by AMD3100 treatment with no significant difference in the total number of single cells, clusters, or colonies identified under the different drug conditions (P=0.19, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=3). To further examine the effect of AMD3100 treatment on ECFC-derived cell proliferation during the first week of the tubule assay, eGFP-transduced CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs were either exposed to 5 μM AMD3100 or no drug from day 0 of coculture. At days 4 and 7 of the assay, tubules were dissociated and the number of eGFP-positive endothelial cells was determined in each well. Figure 4B and Supplementary Fig. S8 illustrate that there is no significant effect of AMD3100 treatment on the proliferation of either CB ECFC-derived cells [P=0.15, n=5 (day 4) or P=0.62, n=6 (day 7) over two experiments, Student's t-test] or HUVECs [P=0.12, n=5 (day 4) or P=0.4, n=6 (day 7), Student's t-tests, over two experiments], respectively, during the first 7 days of the assay when cell proliferation and organization of the immature tubule network occur. The number of unlabeled hDFs was also counted during the first week of the assay, and while exposure to 1 μM AMD3100 over 4 or 7 days did not significantly affect the proliferation of these cells at day 4 or 7 [Fig. 4C, P=0.37, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=6 (day 4), P=0.25, n=6 (day 7), over two experiments], treatment with 5 μM AMD3100 resulted in a significant reduction in the total number of hDFs present by day 7 (Fig. 4C, ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=13 over four experiments). This suggests that chronic treatment over this time period with 5 μM AMD3100 affects hDF proliferation that influences tubule development and integrity and may partially explain why chronic exposure of the cocultures to 5 μM AMD3100 (1) generates a more severe tubule phenotype than 1 μM AMD3100 and (2) inhibits tubule formation more than when the drug is added later during the assay when the vasculature matures. We have previously examined the effects of reducing hDF numbers in a coculture system while maintaining HUVECs at a constant number [36]. Our results showed that if we reduced the ratio of hDFs:HUVECs to below 2:1, the number of vascular tubules began to decline and, if the cocultures contained more HUVECs than hDFs, then HUVECs proliferated on the hDFs rather than forming vascular tubules [36]. Thus, reducing the numbers of hDFs in the coculture simulated the effect of AMD3100 treatment. Together, these data support the hypothesis that CXCL12 does not have a prominent role in controlling the proliferation of ECFC-derived cells during new vessel formation in this coculture system at least in the presence of complete EGM2 media with its added VEGF and FGF-2, but, interestingly, it does affect the proliferation of hDFs under the same growth conditions and this is likely to contribute to impaired tubule development.

FIG. 4.

AMD3100 treatment and cell proliferation. (A) AMD3100 treatment does not inhibit CB ECFC-derived cell or HUVEC proliferation in single-cell clonogenic assays. There is no significant effect on the numbers of clusters, LPP-ECFCs, or HPP-ECFCs observed [P=0.35 (clusters), P=0.87 (LPP-ECFCs), and P=0.26 (HPP-ECFC), one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=3 experiments combining HUVEC- and CB ECFC-derived cell data]. (B) AMD3100 treatment does not inhibit endothelial cell proliferation during vascular tubule development. The total number of eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells per well exposed to either 5 μM AMD3100 or no drug (Control) were counted at days 4 and 7 of the vascular tubule assay. There was no significant difference between the two conditions [P=0.15, n=5 (day 4) or P=0.62, n=6 (day 7) over two experiments, unpaired Student's two-tailed t-test]. (C) The 5-μM AMD3100 treatment significantly reduces hDF cell proliferation during vascular tubule development. The total number of hDFs per well exposed to either 1 and 5 μM AMD3100 or no drug (Control) were counted at days 4 and 7 of the tubule assay. While 1 μM of AMD3100 had no effect on hDF proliferation [P=0.37, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=6 (day 4), P=0.25, n=6 (day 7), over two experiments], 5 μM of AMD3100 reduced the proliferation of these cells at day 7 (***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=13 over four experiments). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. HPP, high proliferative potential; LPP, low proliferative potential.

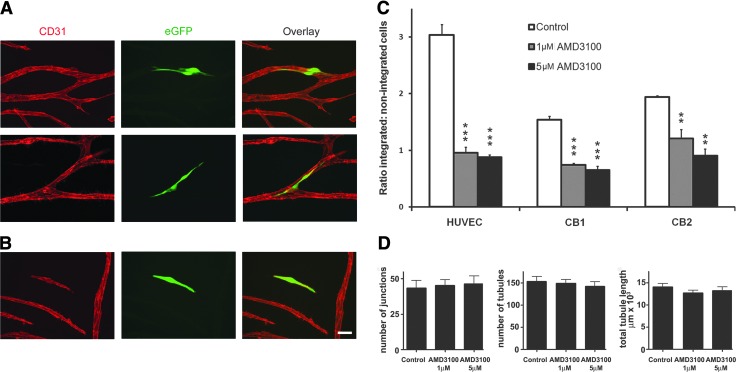

A dual role for AMD3100: AMD3100 modulates the integration of CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs into immature tubule networks

To further understand the effects of CXCL12 and AMD3100 at earlier stages in these cocultures, we devised a cell integration assay based on the observation that exogenously applied ECFC-derived CB cells and HUVECs could integrate into existing immature tubule networks with good efficiency. This assay may serve as a useful model for studying the reformation of the endothelial barrier or repair of vascular integrity. In this assay, unlabeled HUVECs were cocultured with hDFs or hBM MSCs to generate an immature tubule network. At day 6, untreated or AMD3100- (1 or 5 μM for 1 h) pretreated eGFP-labeled HUVECs or CB ECFC-derived cells were added to the cocultures in the presence of AMD3100 for 48 h. After 48 h (at day 8 of culture), the number of eGFP-labeled ECFC integration events (see “Materials and Methods” section) were counted, as were those eGFP-labeled cells that did not integrate. Figure 5A and B illustrates integration or not respectively of exogenously added eGFP CB ECFC-derived cells, while Fig. 5C demonstrates that there was a significant decrease in the ratio of integrated to nonintegrated cell events for both exogenously added HUVECs or CB ECFC-derived cells (***P<0.001 or **P<0.01, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=3 experiments for each cell type) in the presence of either 1 or 5 μM AMD3100, with the latter having a more pronounced effect. Interestingly and as expected when very small numbers of exogenous cells were added to the developing vascular network, tubule analyses of the networks exposed to 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 for 48 h between days 6 and 8 did not reveal any changes in the measured parameters of total tubule number, tubule length, and number of junctions when compared with control cultures (Fig. 5D). This rules out the possibility that fewer eGFP-labeled ECFC-derived cells integrated in response to AMD3100 treatment as a result of a smaller and less complex tubule network.

FIG. 5.

AMD3100 treatment significantly inhibits integration of CB ECFC-derived cells and HUVECs into established but immature tubule networks. (A) Examples of integrated eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells 48 h after addition to the established day-6 vascular tubule network. (B) Example of nonintegrated eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells under the same conditions. Scale bar=50 μm. (C) AMD3100 treatment significantly inhibited the integration of HUVECs or two different batches of CB ECFC-derived cells into an existing tubule network (**P<0.01 and ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=3 for each cell type). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. (D) The tubule phenotypes were quantitated using Angiosys software after eGFP-labeled CB ECFC-derived cells were treated without (Control) or with 1 or 5 μM AMD3100 and then added to the extant vascular tubule network for 48 h as described in the “Materials and Methods” section, but no effects on tubule number, tubule length, or number of junctions were observed in the presence or absence of AMD3100 over this time period. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean, n=3 experiments.

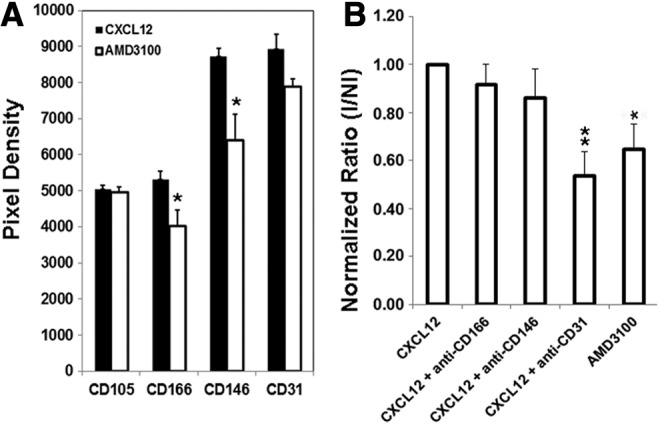

We next assessed whether the expression of candidate cell surface molecules was altered with the exogenous addition of CXCL12 (SDF-1α) to ECFC-derived cells using proteome profiler arrays. It should be noted that HUVECs and CB ECFC-derived cells constitutively produce CXCL12 (113±22 pg/mg vs. 161±19 pg/mg, respectively, n=3 cell batches for each) when cultured for 24 h in the EGM2 integration assay and coculture media. Addition of exogenous CXCL12 for 24 h resulted in a trend toward enhanced expression of CD166, CD31, and CD146 (P=0.05, 0.02, and 0.09, respectively, vs. 0.13 for CD105; Student's t-test) in CB ECFC-derived cells, but not in HUVECs (Supplementary Fig. S9). Further, proteome profiler array analyses of HUVECs revealed a trend for CD166, CD31, and CD146 proteins to be downregulated with AMD3100 treatment compared with addition of exogenous CXCL12 (P=0.04, 0.07, and 0.02, respectively) while CD105 remained unaffected (P=0.65; Fig. 6A). When blocking antibodies to CD166, CD31, and CD146 were added to the cell integration assay described earlier and the integration of the exogenous ECFC-derived cells into immature vascular networks was quantified, the CD31 blocking antibody, but not CD166 nor CD146, significantly reduced exogenous endothelial cell integration in a similar manner to AMD3100 [Fig. 6B; **P<0.01 (CD31) and *P<0.05 (AMD3100), one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=6 over two experiments]. Thus, AMD3100 has a dual effect during intermediate and also at later stages of tubule formation.

FIG. 6.

CD31 blocks integration of exogenous HUVECs into immature vessel networks. (A) Change in expression of CD105, CD166, CD146, and CD31 in whole-cell lysates when cord ECFC-derived cells (HUVECs) were treated with CXCL12 as compared with the addition of AMD3100 to block endogenous CXCL12 stimulation as measured using proteome profiler arrays. Values are means±SEM of four dotblots from two different HUVEC batches and p-values were calculated using unpaired Student's two-tailed t-test, with *P<0.05 being significant. (B) The relative change in the ratio of fully integrated and not fully integrated eGFP-labeled HUVECs stimulated with 150 ng/mL CXCL12 into immature vessel networks in vitro in the presence of isotype controls or respective blocking antibodies—CD166, CD146, and CD31. The values were normalized to CXCL12-treated cells incubated with isotype control antibodies. The effect of 5 μM AMD3100 without antibody blockade is also shown. Significant differences in cells fully integrated into immature vascular networks were observed for AMD3100 versus CXCL12 treatment (*P<0.05) and after blockade with CD31 in the presence of CXCL12 (**P<0.01). Values are means±SEM for n=6 samples and two batches of cells and the P values are calculated using one-way ANOVA with post hoc Bonferroni t-tests, n=6 over two experiments.

Discussion

Multiple stages of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis were studied in our in vitro assay with ECFC-derived cells first forming multicellular structures in the first 2–3 days, before migrating into thread-like tubule structures over the first week and then maturing to form a network of anastomosing vessels by 12–14 days, when cultured in the presence of supporting hDFs or bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells and medium containing VEGF and FGF-2. We initially demonstrated in this assay that the 12G5 epitope of CXCR4, which binds to the chemokine CXCL12, is upregulated during vascular tubule formation. The addition of the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 from the commencement of this coculture assay significantly reduced vascular tubule network formation. This reduction in neovascularization was partly recapitulated by delayed addition of AMD3100, affecting both early and later stages of vascular tubule formation. These results suggested that CXCL12 has a dual role in regulating vessel formation in these 14-day cocultures and this was confirmed by the following studies.

First, we showed that AMD3100, at the later stages of vascular tubule formation, negatively modulated the maturation of the developing network in this coculture system. More specifically, using time-lapse microscopy to analyze the vascular tip cells while they were dynamically extending and retracting between days 9 and 14 as the vascular network was refined in the in vitro cocultures, we demonstrated that AMD3100 inhibited the extension and increased the proportion of retracted vascular tubules. These human studies support and extend those using laser capture microdissection, which demonstrate that Cxcr4 gene expression is enriched in an in vivo model on murine retinal endothelial tip cells that sense guidance cues via extension of filopodia toward Cxcl12 [41]. They are also reminiscent, in the case of Cxcl12- and Cxcr4-deficient mice, of the lack of filopodia and endothelial processes that usually link endothelial cells together in the gastrointestinal tract [42].

Second, we observed that AMD3100 also affected the earlier stages of vascular tubule formation. Our previous studies have shown that AMD3100 at the concentrations used in this article (1 and 5 μM) is not toxic to ECFC-derived cells [36]. The studies described in this article further show that AMD3100 did not significantly affect the proliferation of ECFC-derived cells as assessed in the ECFC clonal cell assay where their ability to form HPP-ECFC, LPP-ECFC, or endothelial clusters was unaltered, nor over the first 7 days in the coculture assay. However, there was a small but significant decrease in the numbers of hDFs in the coculture with 5 μM AMD3100, suggesting that compromising the function of such stromal niche cells can further reduce vascular tubule formation. Studies by other researchers have shown that CXCR4 is upregulated on endothelial cells by VEGF-A, VEGF-C, or FGF-2, that CXCL12 (SDF-1α) acts synergistically with SCF and IL-3 to promote vascular lumen formation in vitro, and that Flt3-ligand or M-CSF can replace SCF as a costimulatory cytokine in this process [39,43]. In this context, we and others have shown that these synergistic factors are differentially produced by hBM MSCs, hDFs, or human UC or CB ECFC-derived cells in vitro [35,36,44–47], so that a loss of supporting stromal cells and hence of their secreted factors would result in reduced tubule formation. Notably, despite the contribution of a number of factors to vessel formation in this assay, blockade of CXCL12 with AMD3100 alone had a significant effect on vascular tubule formation, implying that it is a key molecule in this process.

To analyze this early effect of AMD3100 further, we used a novel assay to demonstrate that integration of exogenously added ECFC-derived cells into an established but immature tubule network was significantly inhibited by 5 μM AMD3100 addition. There was a trend for reduced expression of three molecules involved in endothelial adhesion and/or migration—CD31, CD146, and CD166—on ECFC-derived cells after AMD3100 treatment when compared with CXCL12 stimulation. However, blocking antibodies to CD31 only, but not CD146 nor CD166, significantly reduced exogenous ECFC-derived cell integration into the extant but immature vascular network. CD31 or PECAM-1 is a 130-kDa member of the Ig superfamily, which is highly expressed on endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo [48]. Although studies in mice have demonstrated that CD31 deficiency can be compensated by CD31-independent pathways during development [49], other research, which is consistent with our studies, has shown that CD31 antibodies or deficiency can block endothelial–endothelial interactions and the formation of endothelial tubules in Matrigel assays in vitro, as well as angiogenesis in in vivo murine models [48,50,51]. CD31/PECAM-1 on endothelial cells also contributes to vascular barrier integrity [52] and arteriogenesis [53], to endothelial cell function required for alveolarization [50], and to enhanced retinal vascular density in postnatal mice when comparisons are made with PECAM-1-deficient mice [54]. Of further note, we observed that CD105/endoglin remained unaltered on ECFC-derived cells after AMD3100 treatment and this would be consistent with the regulation of CD105 function by BMP9 [55].

In conclusion, our studies therefore suggest that CXCL12 has two key roles in vascular formation: (1) the extension of endothelial tip-like cells toward the guidance cue, CXCL12, on adjacent endothelial cells and (2) enhancing the integration of ECFC-derived cells into the developing vascular networks, processes inhibited by AMD3100. Our approach to examining the effects of AMD3100 in a complex in vitro microenvironmental model of neovascularization may prove significant for understanding the mechanisms of action of this and other drugs and associated molecules in promoting or inhibiting revascularization and for more clearly defining the experimental approach to testing or assessing the effects of such drugs in vitro and subsequently in vivo. Understanding such mechanisms as those exemplified here with CXCL12 in new blood vessel formation has translational implications that include inhibition of tumor progression and promotion of tissue repair and regeneration as diverse as peripheral arterial disease and ischemic injury, burn injury, neurodegenerative disease, and hematological regeneration [5–7,11,18,22,56–60].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by research funding from National Institutes of Health Research (G.T., C.P.K., R.C., Y.Z., R.G., A.L.H., and S.M.W.), NHS Blood and Transplant (S.E.N., G.T., C.P.K., M.G.R., R.C., Y.Z., R.G., T.A., and S.M.W.), Restore Burns and Wound Healing Trust (T.A. and S.M.W.), the EU Framework VII Cascade grant (S.M.W.), and the Royal College of Surgeons of England (T.A.). T.A. was a recipient of a Duke of Kent Research Fellowship. This article presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) under its Programme Grants scheme (RP-PG-0310-10001 and 10003). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. We would like to thank Mrs. Wendy Slack for her expert assistance with the references.

Author Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Watt M. and Forde SP. (2008). The central role of the chemokine receptor, CXCR4, in haemopoietic stem cell transplantation: will CXCR4 antagonists contribute to the treatment of blood disorders?. Vox Sang 94:18–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Broxmeyer HE. (2008). Chemokines in hematopoiesis. Curr Opin Hematol 15:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanoun M. and Frenette PA. (2013). This niche is a maze; an amazing niche. Cell Stem Cell 12:391–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazennec G. and Richmond A. (2010). Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new insights into cancer-related inflammation. Trends Mol Med 16:133–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li W, Kohara H, Uchida Y, James JM, Soneji K, Cronshaw DG, Zou R, Nagasawa T. and Mukouyama YS. (2013). Peripheral nerve-derived CXCL12 and VEGF-A regulate the patterning of arterial vessel branching in developing limb skin. Dev Cell 24:359–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li M, Hale JS, Rich JN, Ransohoff RM. and Lathia JD. (2012). Chemokine CXCL12 in neurodegenerative diseases: an SOS signal for stem cell-based repair. Trends Neurosci 35:619–628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farouk SS, Rader DJ, Reilly MP. and Mehta NN. (2010). CXCL12: a new player in coronary disease identified through human genetics. Trends Cardiovasc Med 20:204–209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewellis SW. and Knaut H. (2012). Attractive guidance: how the chemokine SDF1/CXCL12 guides different cells to different locations. Semin Cell Dev Biol 23:333–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhuo W, Jia L, Song N, Lu XA, Ding Y, Wang X, Song X, Fu Y. and Luo Y. (2012). The CXCL12-CXCR4 chemokine pathway: a novel axis regulates lymphangiogenesis. Clin Cancer Res 18:5387–5398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox A, Gal S, Fisher N, Smythe J, Wainscoat J, Tyler MP, Watt SM. and Harris AL. (2008). Quantification of circulating cell-free plasma DNA and endothelial gene RNA in patients with burns and relation to acute thermal injury. Burns 34:809–816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fox A, Smythe J, Fisher N, Tyler MP, McGrouther DA, Watt SM. and Harris AL. (2008). Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells into the circulation in burned patients. Br J Surg 95:244–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Clercq E. (2009). The AMD3100 story: the path to the discovery of a stem cell mobilizer (Mozobil). Biochem Pharmacol 77:1655–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peled A, Wald O. and Burger J. (2012). Development of novel CXCR4-based therapeutics. Expert Opin Invest Drugs 213:341–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonig H. and Papayannopoulou T. (2013). Hematopoietic stem cell mobilization: updated conceptual renditions. Leukemia 27:24–31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohty M. and Ho AD. (2011). In and out of the niche: perspectives in mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells. Exp Hematol 39:723–729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shepherd RM, Capoccia BJ, Devine SM, Dipersio J, Trinkaus KM, Ingram D. and Link DC. (2006). Angiogenic cells can be rapidly mobilized and efficiently harvested from the blood following treatment with AMD3100. Blood 108:3662–3667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pitchford SC, Furze RC, Jones CP, Wengner AM. and Rankin SM. (2009). Differential mobilization of subsets of progenitor cells from the bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 4:62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cojoc M, Peitzsch C, Trautmann F, Polishchuk L, Telegeev GD. and Dubrovska A. (2013). Emerging targets in cancer management: role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. Onco Targets Ther 6:1347–1361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carmeliet P. and Jain RJ. (2011). Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications of angiogenesis. Nature 473:298–307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ribatti D. and Crivellato E. (2012). “Sprouting angiogenesis”., a reappraisal. Dev Biol 372:157–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siekmann AF, Affolter M. and Belting HG. (2013). The tip cell concept 10 years after: New players tune in for a common theme. Exp Cell Res 319:1255–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watt SM, Gullo F, van der Garde M, Markeson D, Camicia R, Khoo CP. and Zwaginga JJ. (2013). The angiogenic properties of mesenchymal stem/stromal cells and their therapeutic potential. Br Med Bull 108:25–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheng G, Liao S, Kit Wong J, Lacorre DA, di Tomaso E, Au P, Fukumura D, Jain RK. and Munn LL. (2011). Engineered blood vessel networks connect to host vasculature via wrapping and tapping anastomosis. Blood 118:4740–4749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis GE, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A. and Koh W. (2011). Molecular basis for endothelial lumen formation and tubulogenesis during vasculogenesis and angiogenic sprouting. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 288:101–165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lammert E. and Axnick J. (2012). Vascular lumen formation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a006619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lampugnani MG. (2012). Endothelial cell-to-cell junctions: adhesion and signaling in physiology and pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:pii: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tung JJ, Tattersall IW. and Kitajewski J. (2012). Tips, stalks, tubes: notch-mediated cell fate determination and mechanisms of tubulogenesis during angiogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a006601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakatsu MN, Sainson RC, Aoto JN, Taylor KL, Aitkenhead M, Perez-del-Pulgar S, Carpenter PM. and Hughes CC. (2003). Angiogenic sprouting and capillary lumen formation modeled by human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) in fibrin gels: the role of fibroblasts and angiopoietin-1. Microvasc Res 66:102–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakatsu MN. and Hughes CC. (2008). An optimized three-dimensional in vitro model for analysis of angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol 443:65–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bishop ET, Bell GT, Bloor S, Broom IJ, Hendry NF. and Wheatley DN. (1999). An in vitro model of angiogenesis: basic features. Angiogenesis 3:335–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Friis T, Sorensen BK, Engel AM, Rygaard J. and Houen G. (2003). A quantitative ELISA-based co-culture angiogenesis and cell proliferation assay. APMIS 111:658–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryan BA. and D'Amore PA. (2008). Pericyte isolation and use in endothelial/pericyte coculture models. Methods Enzymol 443:315–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koh W, Stratman AN, Sacharidou A. and Davis GE. (2008). In vitro three dimensional collagen matrix models of endothelial lumen formation during vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Methods Enzymol 443:83–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Y, Fisher N, Newey SE, Smythe J, Tatton L, Tsaknakis G, Forde SP, Carpenter L, Athanassopoulos T, et al. (2009). The impact of proliferative potential of umbilical cord-derived endothelial progenitor cells and hypoxia on vascular tubule formation in vitro. Stem Cells Dev 18:359–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roubelakis MG, Tsaknakis G, Pappa KI, Anagnou NP. and Watt SM. (2013). Spindle shaped human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells from amniotic fluid promote neovascularization. PLoS One 8:e54747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhou B, Tsaknakis G, Coldwell KE, Khoo CP, Roubelakis MG, Chang CH, Pepperell E. and Watt SM. (2012). A novel function for the haemopoietic supportive murine bone marrow MS-5 mesenchymal stromal cell line in promoting human vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Br J Haematol 157:299–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walker NG, Mistry AT, Smith LE, Eves PC, Tsaknakis G, Forster S, Watt SM. and Macneil S. (2012). A chemically defined carrier for the delivery of human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells to skin wounds. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 18:143–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khoo CP, Micklem K. and Watt SM. (2011). A comparison of methods for quantifying angiogenesis in the Matrigel assay in vitro. Tissue Eng Part C Methods 17:895–906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stratman AN, Davis MJ. and Davis GE. (2011). VEGF and FGF prime vascular tube morphogenesis and sprouting directed by hematopoietic stem cell cytokines. Blood 117:3709–3719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ingram DA, Mead LE, Moore DB, Woodard W, Fenoglio A. and Yoder MC. (2005). Vessel wall-derived endothelial cells rapidly proliferate because they contain a complete hierarchy of endothelial progenitor cells. Blood 105:2783–2786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strasser GA, Kaminker JS. and Tessier-Lavigne M. (2010). Microarray analysis of retinal endothelial tip cells identifies CXCR4 as a mediator of tip cell morphology and branching. Blood 115:5102–5110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tachibana K, Hirota S, Iizasa H, Yoshida H, Kawabata K, Kataoka Y, Kitamura Y, Matsushima K, Yoshida N, et al. (1998). The chemokine receptor CXCR4 is essential for vascularization of the gastrointestinal tract. Nature 393:591–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salcedo R, Wasserman K, Young HA, Grimm MC, Howard OM, Anver MR, Kleinman HK, Murphy WJ. and Oppenheim JJ. (1999). Vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor induce expression of CXCR4 on human endothelial cells: in vivo neovascularization induced by stromal-derived factor-1alpha. Am J Pathol 154:1125–1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barbet R, Peiffer I, Hatzfeld A, Charbord P. and Hatzfeld JA. (2011). Comparison of gene expression in human embryonic stem cells, hESC-derived mesenchymal stem cells and human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int 2011:368192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wagner W, Roderburg C, Wein F, Diehlmann A, Frankhauser M, Schubert R, Eckstein V. and Ho AD. (2007). Molecular and secretory profiles of human mesenchymal stromal cells and their abilities to maintain primitive hematopoietic progenitors. Stem Cells 25:2638–2647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nolan DJ, Ginsberg M, Israely E, Palikuqi B, Poulos MG, James D, Ding BS, Schachterle W, Liu Y, et al. (2013). Molecular signatures of tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell heterogeneity in organ maintenance and regeneration. Dev Cell 26:204–219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi H, Butler JM, O'Donnell R, Kobayashi M, Ding BS, Bonner B, Chiu VK, Nolan DJ, Shido K, Benjamin L. and Rafii S. (2010). Angiocrine factors from Akt-activated endothelial cells balance self-renewal and differentiation of haematopoietic stem cells. Nat Cell Biol 12:1046–1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albelda SM, Oliver PD, Romer LH. and Buck CA. (1990). EndoCAM: a novel endothelial cell–cell adhesion molecule. J Cell Biol 110:1227–1237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Duncan GS, Andrew DP, Takimoto H, Kaufman SA, Yoshida H, Spellberg J, Luis de la Pompa J, Elia A, Wakeham A, et al. (1999). Genetic evidence for functional redundancy of platelet/endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1): CD31-deficient mice reveal PECAM-1-dependent and PECAM-1-independent functions. J Immunol 162:3022–3030 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeLisser HM, Helmke BP, Cao G, Egan PM, Taichman D, Fehrenbach M, Zaman A, Cui Z, Mohan GS, et al. (2006). Loss of PECAM-1 function impairs alveolarization. J Biol Chem 281:8724–8731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cao G, Fehrenbach ML, Williams JT, Finklestein JM, Zhu JX. and Delisser HM. (2009). Angiogenesis in platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1-null mice. Am J Pathol 175:903–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Privratsky JR, Paddock CM, Florey O, Newman DK, Muller WA. and Newman PJ. (2011). Relative contribution of PECAM-1 adhesion and signaling to the maintenance of vascular integrity. J Cell Sci 124(Pt 9):1477–1485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen Z, Rubin J. and Tzima E. (2010). Role of PECAM-1 in arteriogenesis and specification of preexisting collaterals. Circ Res 107:1355–1563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dimaio TA, Wang S, Huang Q, Scheef EA, Sorenson CM. and Sheibani N. (2008). Attenuation of retinal vascular development and neovascularization in PECAM-1-deficient mice. Dev Biol 315:72–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Young K, Conley B, Romero D, Tweedie E, O'Neill C, Pinz I, Brogan L, Lindner V, Liaw L. and Vary CP. (2012). BMP9 regulates endoglin-dependent chemokine responses in endothelial cells. Blood 120:4263–4273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Greenfield JP, Cobb WS. and Lyden D. (2010). Resisting arrest: a switch from angiogenesis to vasculogenesis in recurrent malignant gliomas. J Clin Invest 120:663–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kioi M, Vogel H, Schultz G, Hoffman RM, Harsh GR. and Brown JM. (2010). Inhibition of vasculogenesis, but not angiogenesis, prevents the recurrence of glioblastoma after irradiation in mice. J Clin Invest 120:694–705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hooper AT, Butler JM, Nolan DJ, Kranz A, Iida K, Kobayashi M, Kopp HG, Shido K, Petit I, et al. (2009). Engraftment and reconstitution of hematopoiesis is dependent on VEGFR2-mediated regeneration of sinusoidal endothelial cells. Cell Stem Cell 4:263–274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chatterjee M. and Gawaz M. (2013). Platelet-derived CXCL12 (SDF-1α): basic mechanisms and clinical implications. J Thromb Haemost 11:1954–1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Frangogiannis NG. (2011). Stromal cell-derived factor-1-mediated angiogenesis for peripheral arterial disease: ready for prime time?. Circulation 123:1267–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.