Abstract

The young people in the age group of 10-24 yr in India constitutes one of the precious resources of India characterized by growth and development and is a phase of vulnerability often influenced by several intrinsic and extrinsic factors that affect their health and safety. Nearly 10-30 per cent of young people suffer from health impacting behaviours and conditions that need urgent attention of policy makers and public health professionals. Nutritional disorders (both malnutrition and over-nutrition), tobacco use, harmful alcohol use, other substance use, high risk sexual behaviours, stress, common mental disorders, and injuries (road traffic injuries, suicides, violence of different types) specifically affect this population and have long lasting impact. Multiple behaviours and conditions often coexist in the same individual adding a cumulative risk for their poor health. Many of these being precursors and determinants of non communicable diseases (NCDs) including mental and neurological disorders and injuries place a heavy burden on Indian society in terms of mortality, morbidity, disability and socio-economic losses. Many health policies and programmes have focused on prioritized individual health problems and integrated (both vertical and horizontal) coordinated approaches are found lacking. Healthy life-style and health promotion policies and programmes that are central for health of youth, driven by robust population-based studies are required in India which will also address the growing tide of NCDs and injuries.

Keywords: Health promotion, high risk sexual behaviours, India, mental health problems, nutrition disorders, road traffic injuries, substance use, suicides, young people

Introduction

Young people form precious human resources in every country. However, there is considerable ambiguity in the definition of young people and terms like young, adolescents, adults, young adults are often used interchangeably. World Health Organization (WHO) defines ‘adolescence’ as age spanning 10 to 19 yr, “youth” as those in 15-24 yr age group and these two overlapping age groups as “young people” covering the age group of 10-24 yr1. Adults include a broader age range and all those in 20 to 64 yr2. Adolescence is further divided into early adolescence (11-14 yr), middle adolescence (15-17 yr), and late adolescence (18-21 yr)3. Individuals in the age group of 20 - 24 yr are also referred to as young adults4. The National Youth Policy of India (2003) defines the youth population as those in the age group of 15-35 yr5.

Population aged 10-24 years accounts for 373 million (30.9%) of the 1,210 million of India's population with every third person belonging to this age group. Among them, 110 and 273 million live in urban and rural India, respectively. Males account for 195 million and females 178 million, respectively6. As per the National Sample Survey (NSS), (2007-08) 32.8 per cent of this group attend educational institutions and 46 per cent (2004-05) are employed7.

What characterizes adolescents and youth?

Youth - the critical phase of life, is a period of major physical, physiological, psychological, and behavioural changes with changing patterns of social interactions and relationships. Youth is the window of opportunity that sets the stage for a healthy and productive adulthood and to reduce the likelihood of health problems in later years. A myriad of biological changes occur during puberty including increase in height and weight, completion of skeletal growth accompanied by an increase in skeletal mass, sexual maturation and changes in body composition. The succession of these events during puberty is generally consistent among the adolescents often influenced by age of onset, gender, duration, along with the individual variations. These changes are also accompanied by significant stress on young people and those around them, while influencing and affecting their relationships with their peers and adults. It is also an age of impulsivity accompanied by vulnerability, influenced by peer groups and media that result in changes in perception and practice, and characterized by decision making skills/abilities along with acquisition of new emotional, cognitive and social skills3.

Young people's health is vital and crucial

Most young people are presumed to be healthy but, as per WHO, an estimated 2.6 million young people aged 10 to 24 yr die each year and a much greater number of young people suffer from illnesses ‘behaviours’ which hinder their ability to grow and develop to their full potential. Nearly two-thirds of premature deaths and one-third of the total disease burden in adults are associated with conditions or behaviours initiated in their youth (e.g. tobacco use, physical inactivity, high risk sexual behaviours, injury and violence and others)8. The behavioural patterns established during this developmental phase determine their current health status and the risk for developing some chronic diseases in later years9. A significant reduction in the mortality and morbidity of communicable, maternal and neonatal disorders since 1990 due to concerted and integrated efforts10,11 led to a shift in focus towards the health, safety and survival of the young people. It is crucial to understand health problems of this population, processes and mechanisms that affect their health, identify interventions and strategic approaches that protect their health and develop and implement policies and programmes.

The present review focuses on the health behaviours and problems affecting young people in the age group of 10-30 yr in India. The review also examines some policy initiatives and interventions and identifies issues that need to be addressed for health and safety of young people in India.

Review methods

All available population based studies (with large sample size, being multicentric in nature, covering urban and rural areas), independent studies and reports published since 2001 were considered. Searches were conducted using PubMed, Medline, Ovid, Karger, ProQuest, Sage Journals, Science Direct, Springer, Taylor & Francis and Wiley Online Library. Various search terms and key words were used, including young, youth, adolescent, young adult and outcomes of interest namely undernutrition, obesity, overweight, common mental health problems, stress, depression, suicide, alcohol, tobacco use, substance use, violence and road traffic injury. All efforts were made to retrieve the unpublished reports by contacting individual researchers. Case reports and case series were excluded from the search.

From a methodological perspective, majority of the studies were cross-sectional in nature, on varying sample size and undertaken in urban and rural (or both) areas. As there are no comprehensive studies that have focussed on all health problems of this age group, studies have been individualistic in nature based on researchers’ and/or organisational interest. Further, definitions used for age cut-offs and condition under investigation, screening and diagnostic assessments, nature of study, reporting bias, statistical methods add to the complexities of the problem and thus, studies are non-comparable in nature.

Health problems of young people

Although adolescence and young adulthood are generally considered healthy times of life, several important public health and social behaviours and problems either start or peak during these years12. Most of these problems are linked with social determinants and lifestyles operating and interacting in complex environments that precipitate or trigger these conditions or behaviours. Developmental transition of young people make them vulnerable particularly to environmental, contextual or surrounding influences13. Environmental factors, including family, peer group, school, neighbourhood, policies, and societal cues, can both support or challenge young people's health and well-being12.

Available evidence indicates that young people are prone to a number of health impacting conditions due to personal choices, environmental influences and lifestyle changes including both communicable and non-communicable disorders and injuries. Others include substance use disorders (tobacco, alcohol and others), road traffic injuries (RTIs), suicides (completed and attempted), sexually transmitted infections (STI) including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, teen and unplanned pregnancies, homelessness, violence and several others. In all countries, whether developing, transitional or developed, disabilities and acute and chronic illnesses are often induced or compounded by economic hardship, unemployment, sanctions, restrictions, poverty or poorly distributed wealth at both individual and country level14.

Undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies

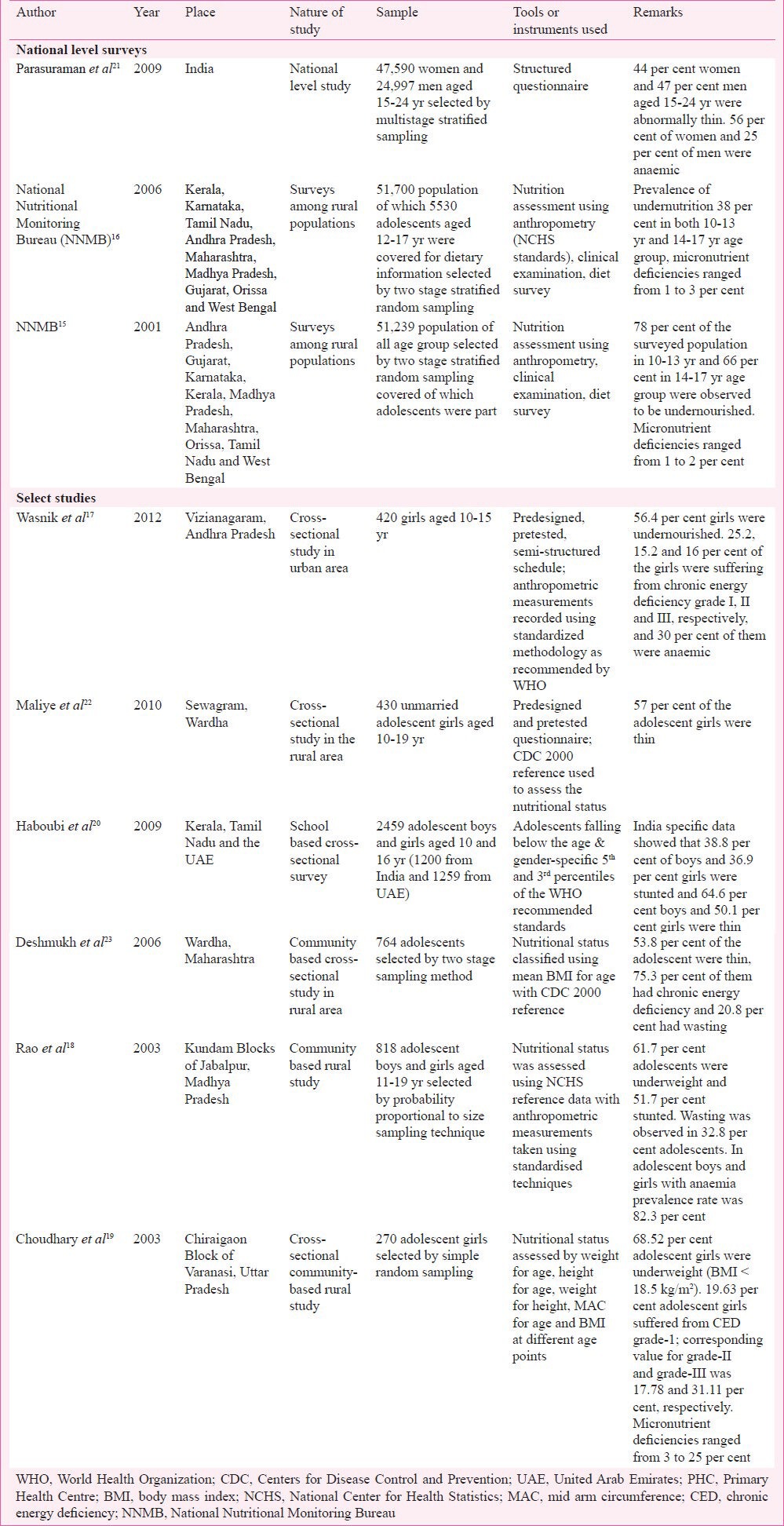

Data shown in Table I indicate a high prevalence of undernutrition and stunting in the age group of 10-30 yr that has an adverse bearing on their health. Data from Nutrition Survey of National Institute of Nutrition during 2001 and 2006 showed that more than half the population aged 10-18 yr was undernourished15,16. This observation is also supported by other studies with sample size varying from 500 to 1000 with the prevalence of undernutrition in 10 to 24 yr ranging from 56.4 to 68.5 per cent17,18,19. A school based study showed that 38.8 per cent of boys and 36.9 per cent of girls were stunted20, while a community based study showed that 51.7 per cent adolescents were stunted18. The prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies in rural area was as high as 25 per cent as reported by Choudhary et al19 with high prevalence of anaemia, more among girls, ranging from 30-82 per cent17,18,21. Anaemic adolescent mothers are at a high risk of miscarriage, maternal mortality and still births; also, low birth weight babies with low iron reserves24. Poor nutritional status of adolescents is an outcome of socio-cultural, economic and public policies relating to household food security compounded by behavioural dimensions.

Table I.

Status of undernutrition and micronutrient deficiency in India

Overweight and obesity

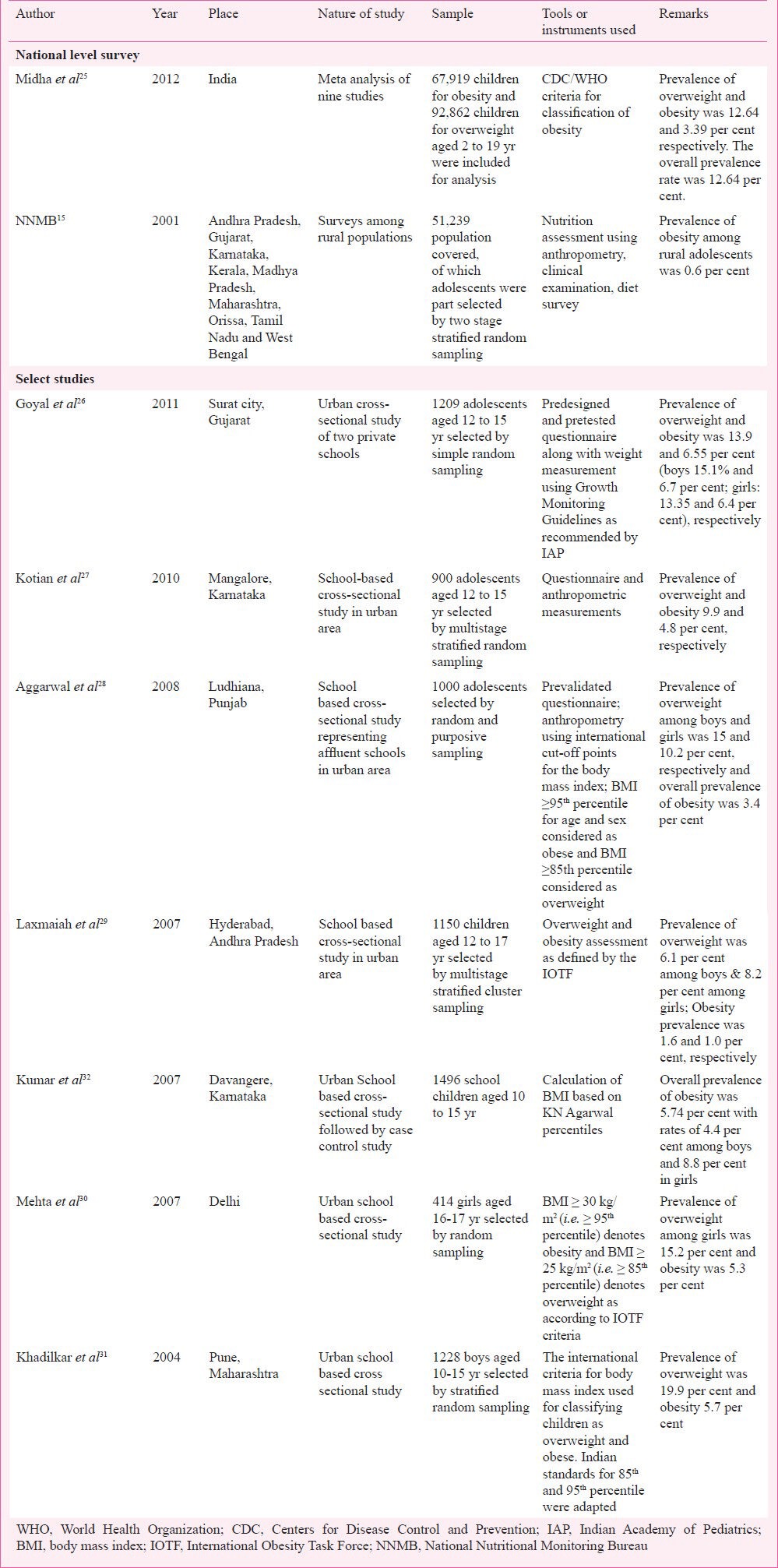

Conversely, overweight and obesity - another form of malnutrition with serious health consequences is increasing among other young people in India and other Low Middle Income Countries (LMICs)8. A meta-analysis of nine studies in 2012 showed 12.6 per cent of children to be overweight and 3.3 per cent to be obese indicating the seriousness of the situation23. A review of a few select studies (Table II) during 2001 to 2012 showed a prevalence of overweight among children aged 10-19 yr to be 9.9 to 19.9 per cent; high in both boys (3 to 15.1%) and girls (5.3 to 13.3%) indicating early onset of obesity26,27,28,29,30,31,33 affecting more of urban school adolescents (3.4 to 6.5%)26,27,28,32 as compared to 0.6 per cent among the rural adolescents15 with significant gender variations26,29,32. Studies from Karnataka27,32 have shown a higher prevalence of obesity as compared to studies from northern India26,28,30. It is clear that India is facing the dual burden of undernutrition and overnutrition as also seen from other reports34,35. There is also a challenge of nutritional transition as Indians are moving away from traditional diets high in cereal and fiber to more western pattern diets high in sugars, fat, and animal-source food (fast food culture) that are closely associated with different non communicable diseases (NCDs) seen in later years36,37.

Table II.

Prevalence of overweight and obesity as reported in Indian studies

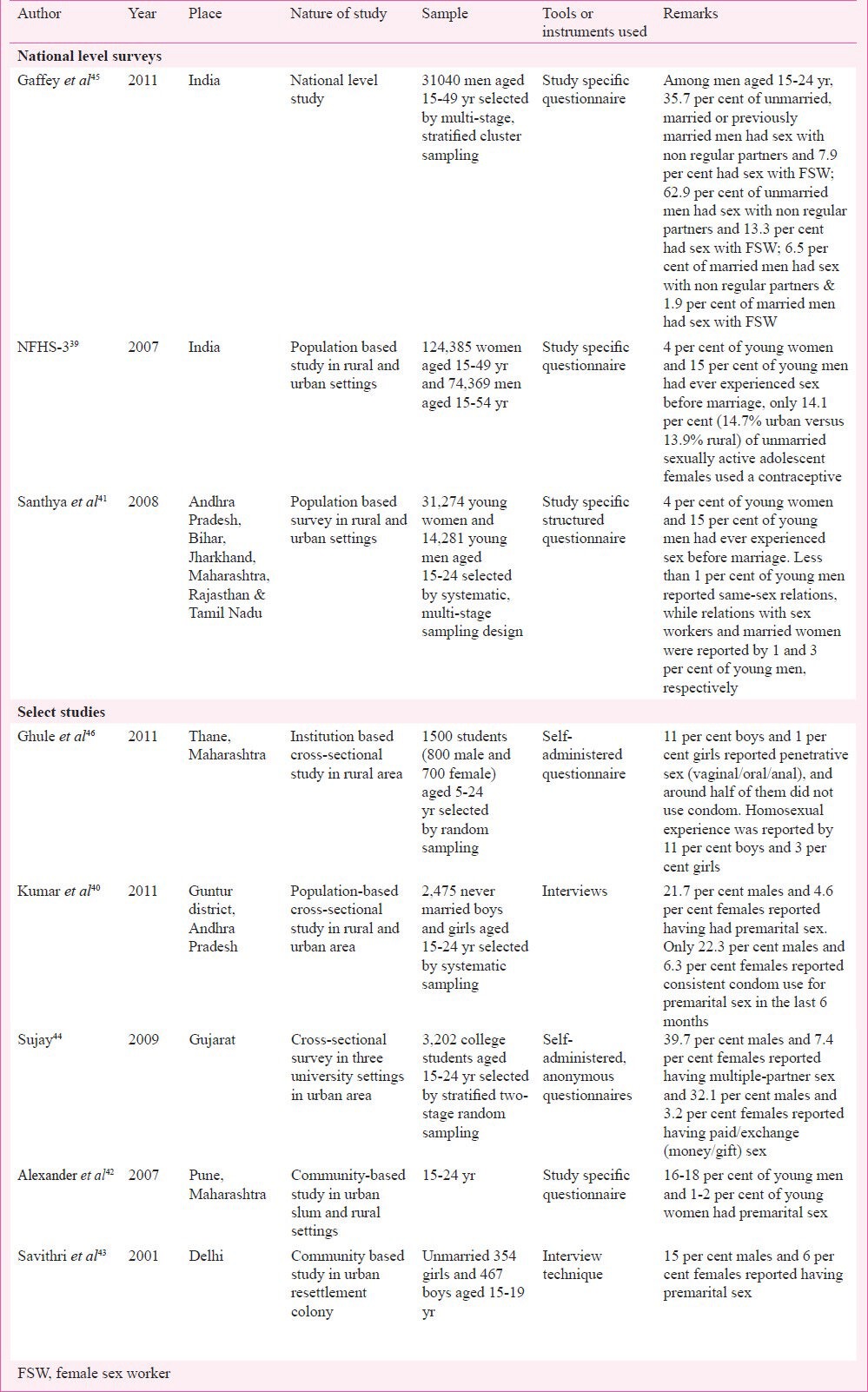

High risk sexual behaviour

High-risk sexual behaviour is a broad term covering early sexual activity especially before 18 years of age and includes unprotected intercourse without male or female condom use except in a long-term, single-partner (monogamous) relationship, unprotected mouth-to-genital contact except in a long-term monogamous relationship, having multiple sex partners, having a high-risk partner (one who has multiple sex partners or other risk factors), exchange of sex (sex work) for drugs or money, having anal sex or having a partner who does except in a long-term, single-partner (monogamous) relationship and having sex with a partner who injects or has ever injected drugs38. It is a known risk factor that puts individuals at risk for contracting HIV/AIDS and a range of other sexually transmitted diseases like gonorrhoea, herpes, genital warts, Chlamydia, syphilis, trichomoniasis, etc. The National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 3 (2005-06) indicated that 4 per cent of young women and 15 per cent of young men had ever experienced sex before marriage and only 14.1 per cent (14.7% urban vs 13.9% rural) of unmarried sexually active adolescent females used a contraceptive39. Young people aged 15 to 24 yr commonly engage in premarital sex more so in men (15-22%) as compared to women (1-6%)39,40,41,42,43. Kumar et al40 in a study of 2,475 never married boys and girls noticed that only 22.3 per cent males and 6.3 per cent females reported consistent condom use for premarital sex in the last 6 months. A study from Gujarat observed that nearly 40 per cent males and 7.4 per cent females in the age group of 15 to 24 yr reported having multiple-partner sex, while 32.1 per cent males and 3.2 per cent females reported having paid/exchange (money/gift) sex44. Thus, data shown in Table III indicate that prevalence of high risk sexual behaviour among the young people is not only high but vary widely across studies and needs immediate attention to reduce the occurrence of HIV and related diseases.

Table III.

Prevalence of high risk sexual behaviour among young Indians

Common mental disorders

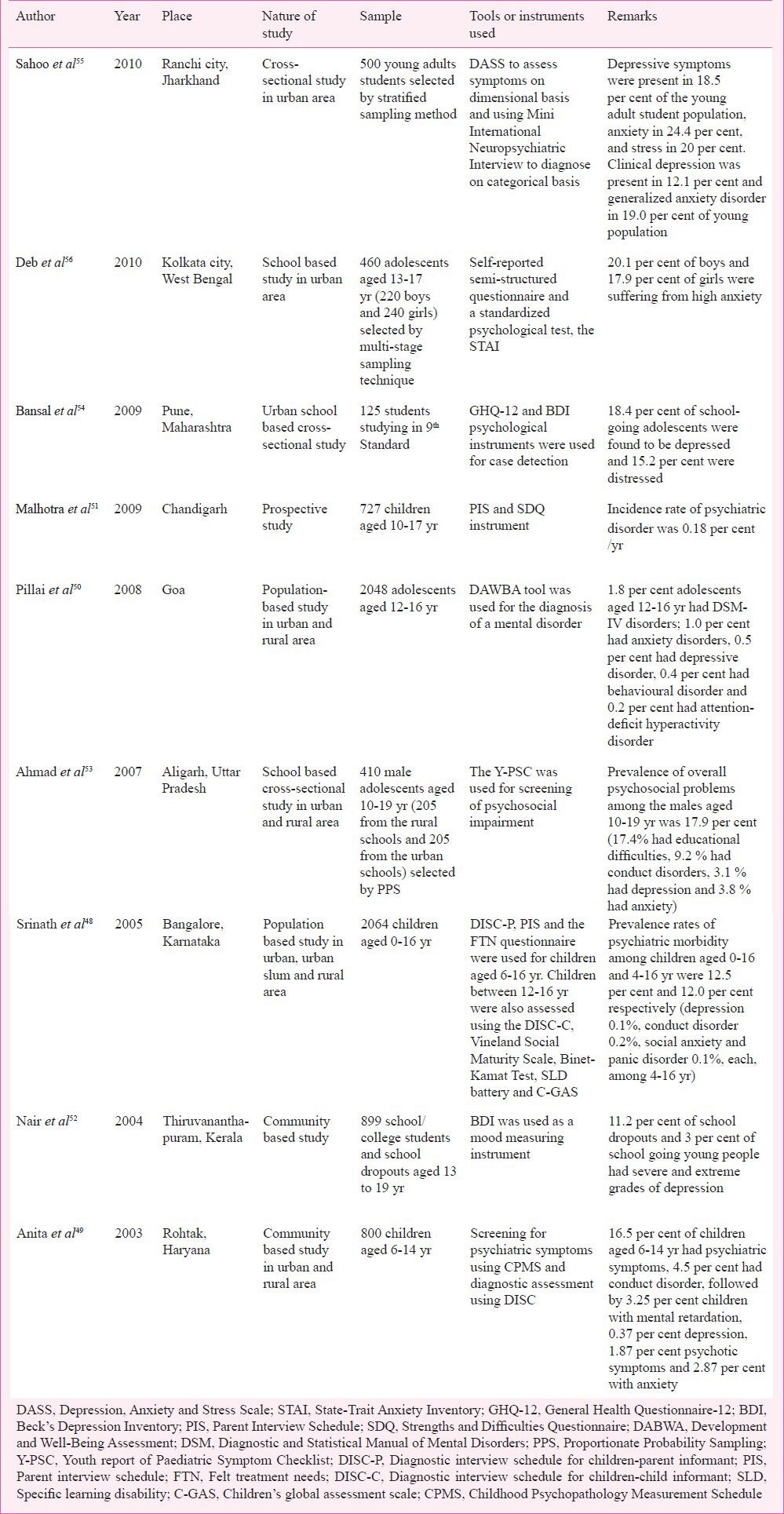

At least 20 per cent of young people are likely to experience some form of mental illness - such as depression, mood disturbances, substance abuse, suicidal behaviours, eating disorders and others8. A meta-analysis of five psychiatric epidemiological studies yielded an estimated prevalence of mental morbidity including 16 mental and behavioural disorders (classified into eight groups of organic psychosis, schizophrenia, manic affective psychosis, manic depression, endogenous depression, mental retardation, epilepsy, phobia, generalized anxiety, neurotic depression, obsession and compulsion, hysteria, alcohol/drug addiction, somatisation, personality disorders and behavioural/emotional disorders) of 22.2 per 1000 population among 15 to 24 years47.

Data available from community based studies on common mental disorders in India depict a high prevalence among the young people (Table IV), but comparisons and extrapolations need to be cautiously made due to variations across studies. The prevalence of overall psychiatry morbidity (depression, conduct disorder, social anxiety, panic disorder) among adolescents has varied from 12 to 16.5 per cent48,49. Pillai et al observed a low prevalence of 1.8 per cent of DSM-IV disorders among adolescents aged 12-16 yr which was attributed to methodological factors and the presence of protective factors50. A six years follow up study in Chandigarh showed the incidence rate of psychiatric disorder to be 0.18 per cent per year among the 10-17 yr old adolescents51. Among the few specific common mental disorders, the prevalence of depression has varied from 0.1 to 18.5 per cent48,49,52,53,54,55, conduct disorders from 0.2 to 9.2 per cent48,49,53, and anxiety from 0.1 to 24.4 per cent48,49,50,53,55,56 across different studies. Two studies showed prevalence of severe and extreme grade of depression in 11.2 per cent of the school dropouts and 3 per cent among the school going adolescents aged 13 to 19 yr and 18.4 per cent among the 9th standard students using Beck's depression Inventory52,54. Promoting mental health and responding to problems on a continuous basis requires a range of adolescent-friendly health care and counselling services in communities57.

Table IV.

Common mental disorders among young Indians

Stress

Stress is a consequence of or a general response to an action or situation arising from an interaction of the person with his environment and places special physical or psychological demands, or both, on a person. The physical or psychological demands from the environment that cause stress, commonly known as stressors and the individual reaction to them take various forms and depends on several intrinsic and/or extrinsic factors. Significant difficulties have been experienced in quantifying and qualifying stress. Some studies have tried to quantify the stress levels among young people, while others have given a mean stress score (influenced by methods of measuring stress)58,59. Sahoo et al55 using Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS) observed that 20 per cent young adults experienced stress. Dabut et al60 using life stress scale found that among adolescent girls studying in 12th standard from Hisar and Hyderabad, 47.5 and 72.5 per cent, were in the moderate category of family stress; financial stress was reported by 60 and 50 per cent and, 90 and 85 per cent had moderate level of social stress, respectively. Sharma & Sidhu in a study, among adolescents aged 16-19 yr using self-made questionnaire based on Bisht Battery of Stress found that 90.6 per cent adolescents had academic stress61.

Suicide

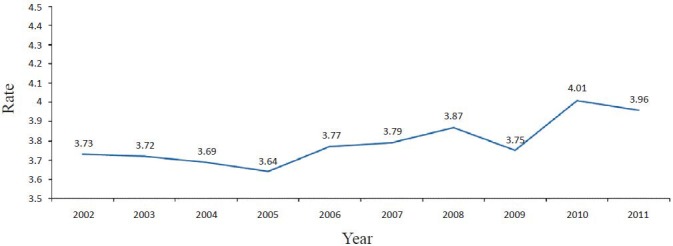

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates about one million people commit suicide each year62. In India, nearly 1,36,000 persons voluntarily ended their lives in a suicidal act as per official reports in 201163. The official report indicates that age specific suicide rate among 15-29 yr is on the rise increasing from 3.73 to 3.96 per 1,00,000 population per year from 2002 to 201163 (Fig. 1). About 40 per cent of suicides in India are committed by persons below the age of 30 yr64. The Million Death Study using RHIME (Representative, Re-sampled, Routine Household Interview of Mortality with Medical Evaluation) method revealed the annual mortality rates to be 25.5 and 24.9 per 1,00,000 population among males and females aged 15-29 yr65, respectively. Other studies have shown incidence among young individuals to vary from 100.1 to 72.2 per 1,00,000 population66. Study from Bangalore showed that of the 5115 attempted suicide covering all age groups, 2.1, 8.4 and 28.6 per cent individuals were in the age group 10-15, 16-20 and 21-25 yr, respectively; and among 912 completed suicides, 2.2, 16.2 and 21.6 per cent were in the age group 10-15, 16-20 and 21-25 years, respectively67. The suicide rates among young females were high (152 per 1,00,000) compared to suicide rates among young men being 69 per 1,00,000 as reported by Aaron et al66 with similar observations by other authors65,68. Soman et al69 found an age specific suicide incidence rates among males and females aged 15-24 yr to be 5.1 and 8.1 per 1,00,000 population per year69. Suicidal ideas and attempts were also found to be high in Chandigarh70 and South Delhi71 with nearly 6 per cent of individuals aged 11-17 yr and 15.8 per cent adolescents aged 14 to 19 yr reporting suicidal ideas, while 0.4 per cent students aged 11-17 yr and 5.1 per cent students aged 14 to 19 yr reported suicidal attempts.

Fig. 1.

Completed suicide among 15-29 yr per 100,000 population from 2002 to 2011 (rate/1,00,000 population). Source: Ref. 63.

Tobacco use

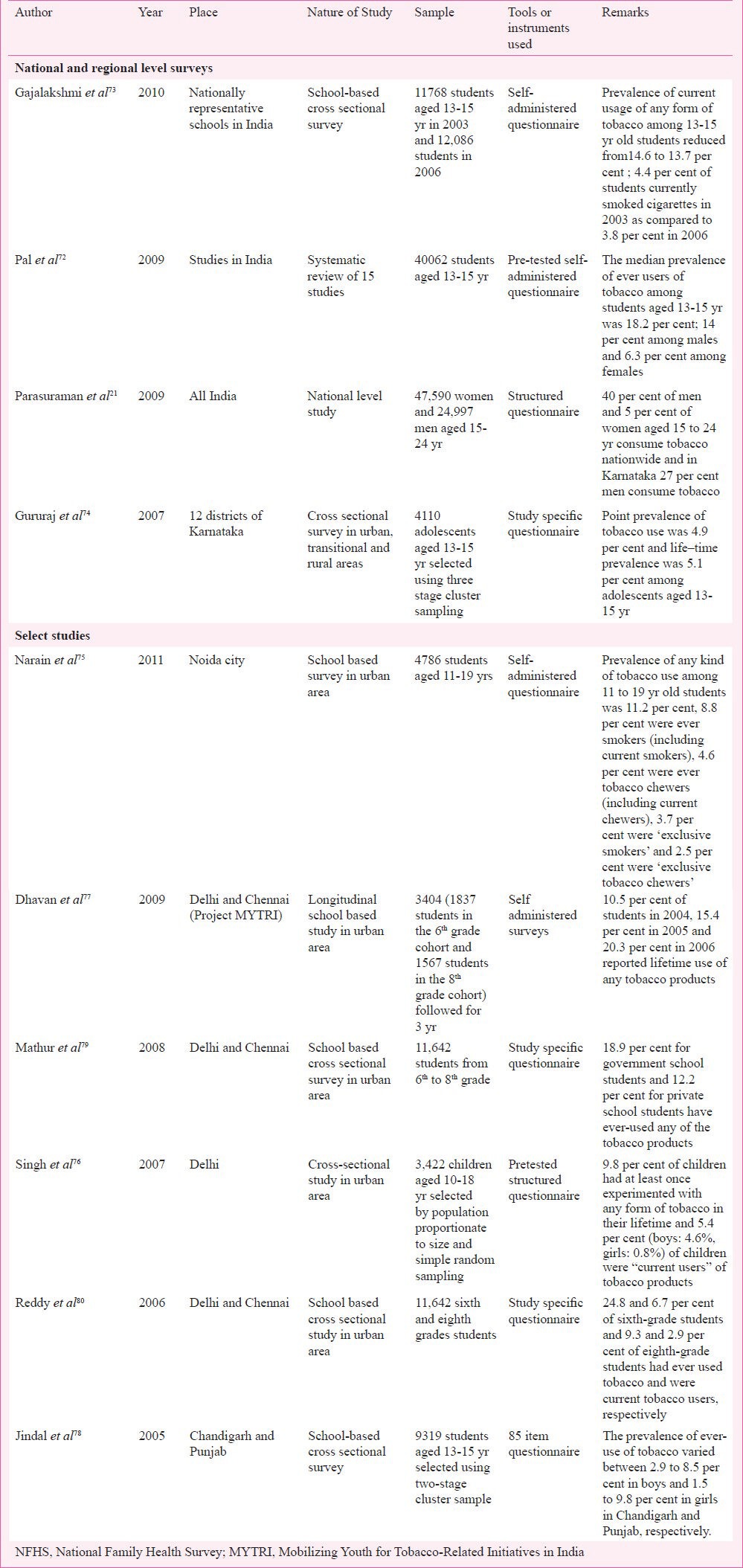

The vast majority of tobacco users worldwide begin the use of tobacco during adolescence. Currently, more than 150 million adolescents use tobacco, and this number is increasing globally57. NFHS-3 revealed that 40 per cent of males and 5 per cent of females aged 15 to 24 yr consumed tobacco nationwide21. Systematic review of 15 studies across India aged 13-15 yr showed a median prevalence of tobacco use (ever users) to be 18.2 per cent; 14 per cent among males and 6.3 per cent among females72. Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS) 2006 and 2009 across India covering 13 to 15 yr old adolescents in 180 schools highlighted an increase in the current users of any form of tobacco from 13.7 to 14.6 per cent and current users of cigarette from 3.8 to 4.4 per cent from 2006 to 200973. A study from Karnataka showed 4.9 per cent point prevalence and 5.1 per cent life-time prevalence of tobacco use among adolescents aged 13-15 yr74, while a study from Noida city indicated that 11.2 per cent of adolescents aged 11 to 19 yr were users of any kind of tobacco75. Other studies have shown 9.8 to 20.3 per cent life time prevalence of any tobacco products among adolescents76,77. Gender variations for usage of any kind of tobacco varied from 2.9 to 8.5 per cent in boys and 1.5 to 9.8 per cent in girls78. The study in Noida city also found that 8.8 per cent of adolescents aged 11 to 19 yr were ‘ever smokers’ (including current smokers), 4.6 per cent were ‘ever tobacco chewers (including current chewers), 3.7 per cent were ‘exclusive smokers’ and 2.5 per cent were ‘exclusive tobacco chewers’75. Data from several studies (Table V) clearly point to the fact that tobacco addiction is emerging as a big threat among young Indians.

Table V.

Prevalence of tobacco use in young people

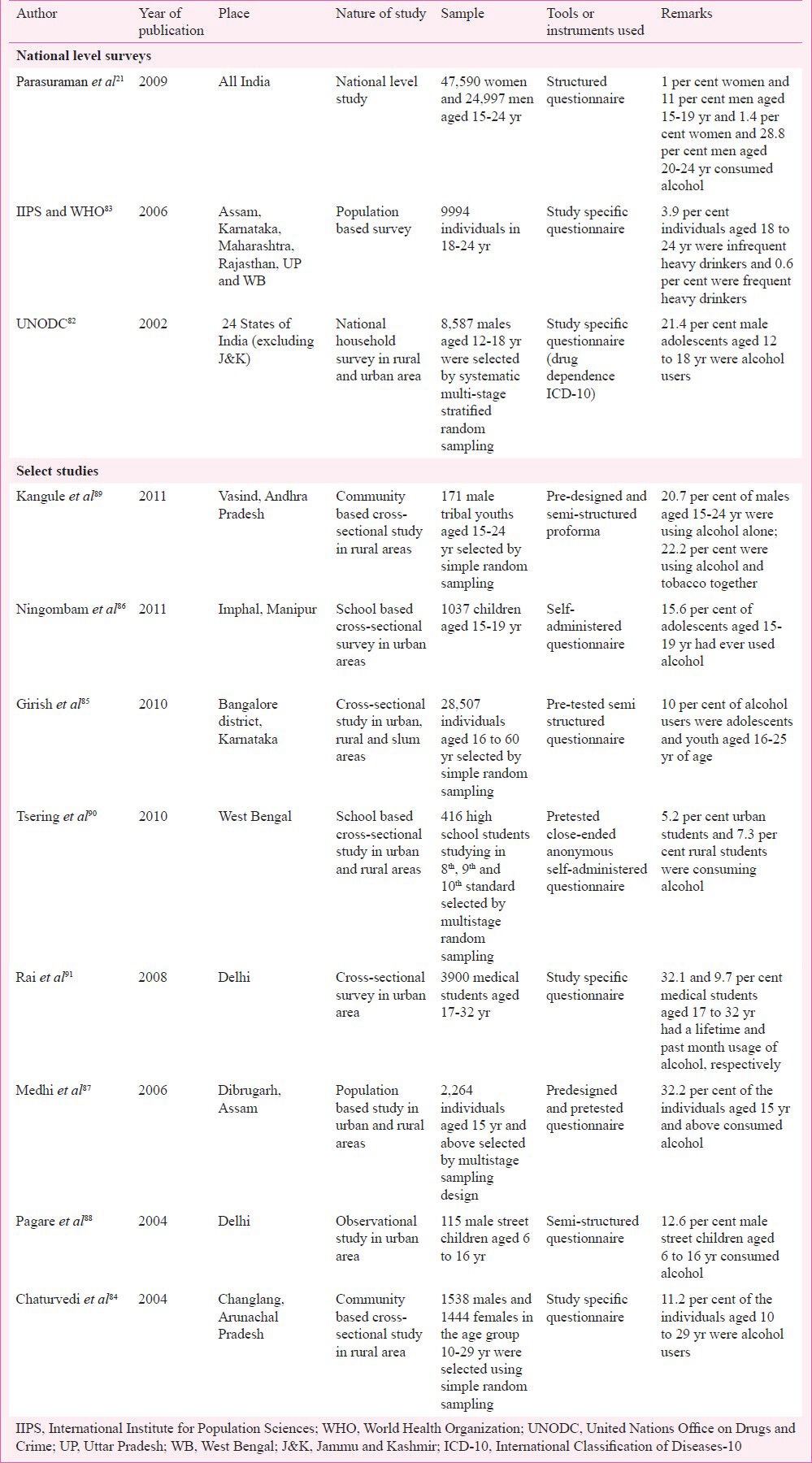

Harmful alcohol use

Harmful drinking among young people is an increasing concern in many countries and is linked to nearly 60 health conditions. It increases risky behaviours and is linked to injuries and violence resulting in premature deaths57. A national review on harmful effects of alcohol reported greater social acceptability of drinking, increasing consumption in rural and transitional areas, younger age of initiating drinking, and phenomenal socio-economic and health impact, more so among young people81. Data from the National Household Survey (NHS) by United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), 2002 covering urban and rural areas of 24 States of India revealed a prevalence of 21.4 per cent of alcohol use among men aged 12 to 18 yr82. The World Health Survey - India reported that among individuals aged 18 to 24 yr, 3.9 per cent were infrequent heavy drinkers and 0.6 per cent were frequent heavy drinkers83. The NFHS-3 survey showed that 1 per cent women and 11 per cent men aged 15-19 yr and 1.4 per cent women and 28.8 per cent men aged 20-24 yr consumed alcohol21. Other population based studies have shown the prevalence of alcohol consumption varying from 1.3 to 15.6 per cent across studies84,85,86,87 with a high consumption among males (12.6 to 20.7%)88,89 and more in urban (5.2%) as compared to rural (7.3%) areas90 (Table VI).

Table VI.

Alcohol use prevalence and patterns among young adults

Other substance use disorders

Substance abuse apart from tobacco and alcohol is one of the major emerging problems among the young population and needs to be tackled effectively. The National Household Survey by UNODC showed that 3.0 per cent of males consumed cannabis and 0.1 per cent opiates82 with common substances used being alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, cocaine and heroin84,86,88,89,90,91,92,93. Studies have shown that non tobacco substance abuse is common, nearly 30 per cent, among street children92 with 57.4 per cent of the male street children aged 6 to 16 years having indulged before coming to the observation home88. Around 43 per cent adolescents indulge in substances abuse93 with 58.7 per cent of the students having used one or more substances at least once in life, while 31.3 per cent regularly use one or more substances94. Chaturvedi et al reported that among 10-29 yr old individuals, apart from tobacco and alcohol use, 2.2 per cent of men and 0.3 per cent of women were opium users84. The use of prescription drugs (benzodiazepines and opiods) has also been a matter of great concern with its overuse being 16.2 per cent91. Data on prevalence of injecting drug users available in India, showed that 5.6 and 14.4 per cent of the males in the age group of 20-24 yr and 25-29 yr, respectively were injecting drug users95. The data from the National Health Survey suggested that about 0.1 per cent of the male population (12-60 yr) reported ever injecting any illicit drug. Injecting drug use was reported more often from the NE region of the country82.

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs)

NCDs include a number of conditions that are behaviour linked and lifestyle related in nature. Indian population, especially young people, is passing through a nutritional transition and is expected to witness higher prevalence of adult non-communicable diseases such as hypertension, diabetes and chronic lung diseases in the coming years.

At the Indian level, a few studies have shown hypertension among the young people to vary from 2.4 to 5.9 per cent comparable to global level (4.5%)96,97,98,99. In another Indian study, hypertension (first instance) was seen in 10.10 per cent of normal weight, 17.34 per cent of overweight and 18.32 per cent of obese children100. The prevalence of youth-onset type 2 diabetes is increasing worldwide in parallel with the obesity epidemic. Study from Chennai reported a temporal shift in the age at diagnosis of type 2 diabetes to a younger group with a prevalence of 3.7 per cent among 20-29 yr101. A study from Delhi also reported a high prevalence of insulin resistance in post pubertal children which was associated with excess body fat and abdominal adiposity102. Chronic lung diseases are also increasing among the young and globally, approximately one in ten young people have asthma99. A study among the school going children (5-15 yr) using modified ISAAC questionnaire in Jaipur city showed 7.59 per cent children to have asthma (in last 12 months)103 and 4.9 per cent in another study in South India104.

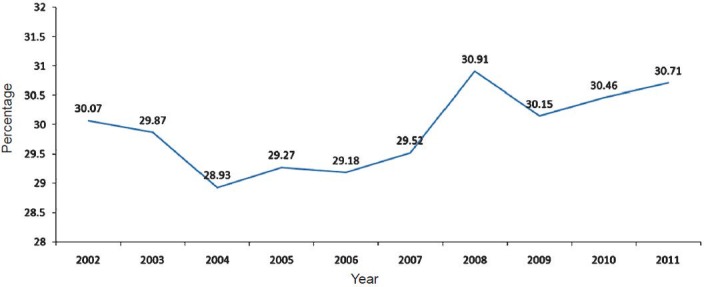

Road traffic injuries (RTIs)

Road traffic injuries (1,85,000 deaths; 29 per cent of all unintentional injury deaths) are the leading cause of unintentional injury mortality in India105. National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) report of 2011 of India showed that 31.3 per cent of the road traffic deaths were seen among 15 to 29 years individuals63 (Fig. 2). Transport Research Wing of the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MORTH) revealed that of the total road accident casualties, 30.3 per cent were in the age group of 15-24 yr106. The Registrar General of India (in 2001-03) showed that motor vehicle injuries contributed to 3.7 per cent of deaths in 5-14 years and 6.9 per cent deaths in 15-24 years (1.7 and 12.4% in females and males, respectively)107. A survey of 20,000 households covering 96,414 individuals in Bangalore found that deaths due to RTIs among children aged 6-15 yr ranged from 5 to 20 per cent and serious injuries from 10-21 per cent and over half of all killed and seriously injured in RTIs occurred to the young adults aged 16-45 yr, more so among those aged 16-30 yr108. The Bangalore Injury Surveillance Project has reported that 38.9 and 36 per cent in 15-29 yr age group had fatal RTI in urban and rural areas, respectively, while 36 per cent had non-fatal RTI in both areas among the same age group109. Sharma et al from Chandigarh110 reported that RTI constituted 11 per cent of the total unnatural deaths among 16-20 yr age group. The incidence of non fatal RTIs among children examined in a few studies revealed that the age-sex adjusted incidence rate among 5-14 yr age group was 18.5 per cent and the age-sex-adjusted annual rate of RTI requiring recovery period of >7 days was 5.8 per cent111. The same authors reported an annual non-fatal RTI incidence rate adjusted for sex among 10-14, 15-19 and 20-29 yr of 23.5, 30.1 and 20.9 per 100 persons per year, respectively112.

Fig. 2.

Trend of road traffic injuries among 15-29 yr old individuals from 2002 to 2011 in India. Source: Ref. 63.

Violence

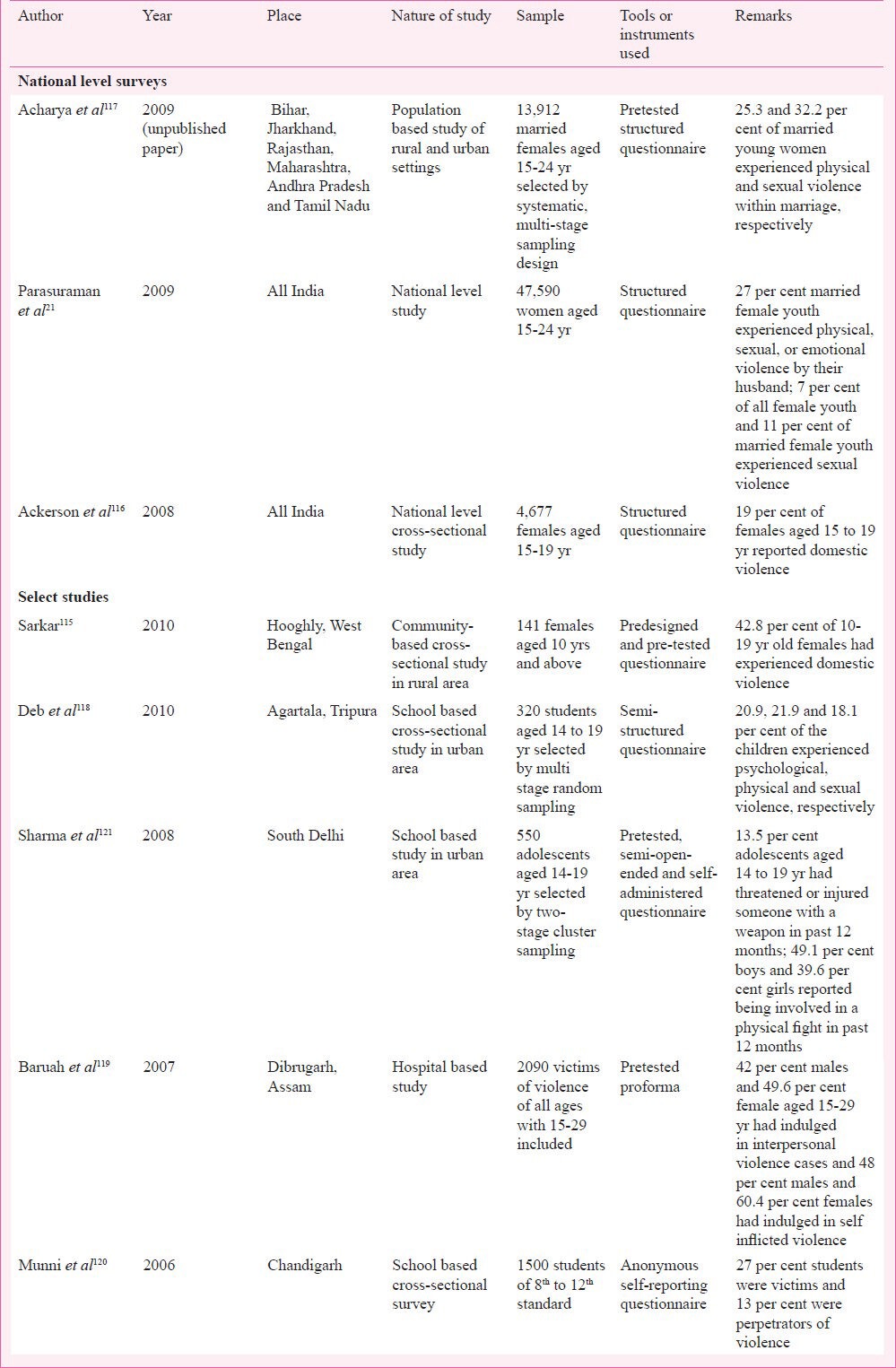

The WHO defines violence as “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, mal development or deprivation”113. Interpersonal violence among youth ranging from minor acts of bullying to severe forms of homicide contribute greatly to the burden of premature death, injury and disability; harming not just the affected but also their families, friends and communities. An average of 565 adolescents and young adults between the ages of 10 and 29 yr die each day as a result of interpersonal violence across the world114. NFHS-3 from India revealed that 27 per cent married young females experienced physical, sexual, or emotional violence by their spouse and 7 per cent of all females and 11 per cent of married females experienced sexual violence21. Studies from India (Table VII) reported that 19 to 42.8 per cent of adolescent females had experienced domestic violence115,116 and 25.3 and 32.2 per cent of young married women experienced physical and sexual violence within marriage, respectively117. Deb et al118 in a sample of students aged 14 to 19 yr showed that 20.9, 21.9 and 18.1 per cent of the children experienced psychological, physical and sexual violence, respectively. Sharma et al121 showed that 13.5 per cent adolescents aged 14 to 19 yr had threatened or injured someone with a weapon in the past 12 months; 49.1 per cent boys and 39.6 per cent girls reported being involved in a physical fight in the past 12 months. Both the genders were commonly involved in inter-personal violence as shown by Baruah and Baruah119 where 42 per cent males and 49.6 per cent female aged 15-29 yr had indulged in interpersonal violence and 48 per cent males and 60.4 per cent females had indulged in self inflicted violence.

Table VII.

Prevalence and pattern of violence among young people

Multiple health behaviours and co-morbid conditions

It is important to highlight that some behaviours and conditions listed above and several others not covered here do not occur in isolation but are often seen as coexisting behaviours and as co-morbid conditions. It is widely acknowledged that tobacco and alcohol use coexists, while binge drinking is closely linked to road crashes and violence. Alcohol is linked to more than 60 health problems and a variety of social issues ranging from domestic violence to diabetes. Similarly, depression and obesity are closely linked to a number of NCDs and depression in particular with suicides. The Health Behaviour Study in Bangalore covering nearly 10,000 individuals aged 18 to 45 yr from urban, rural, slum and transitional areas reported that 30 per cent had more than five behaviours/conditions existing in the same individual122. Evidence from National Household Survey showed that over 26 per cent adult men found to be alcohol users also had higher prevalence of STIs123. Thus, it becomes apparent that while addressing one problem becomes critical, addressing multiple issues in an integrated manner becomes a need in health policies and programmes.

Responding to the challenge

The importance of investing in youth has been recognized in India's Constitution. One of the Directive Principles of State Policy, states that “…it is imperative that children are given opportunities and facilities to develop in a healthy manner and in conditions of freedom and dignity and that childhood and youth are protected against exploitation and against moral and material abandonment”124. Policies and programmes focussing on education [National policy on education (1986 modified in 1992)125, Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan126, Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan]127, welfare [National Policy for the Empowerment of Women (2001)128; Balika Samridhi Yojana, 1997129; National Policy on Child Labour, 1987]130, employment (Swarnjayanti Gram Swarozgar Yojana)131 and others (National Policy for Persons with Disabilities)132 have included young people and highlight health as one of the components. In many of these, the detailed implementation – monitoring and evaluation plan are not elaborated in detail and their impact needs to be examined in detail.

Some of the health policies and programmes have also given a place for youth; a few have a specific youth health focus while others make an indirect mention. The Implementation Guide for State and District Programme Managers under National Rural Health Mission notes that “friendly services are to be made available for all adolescents, married and unmarried, girls and boys”133. Some of these are also focussed on mothers and children. The National Population Policy 2000, the National Health Policy 2002 and the National AIDS Prevention and Control Policy 2002 have all articulated India's commitment to promoting and protecting the health and rights of adolescents and youth, including those relating to mental, and sexual and reproductive health134. The Recent National Programme on Prevention and Control of Cancer, Cardiovascular Diseases, Diabetes and Stroke also has a focus on health promotion and early recognition of health impacting behaviours.

The exclusive National Youth Policy of 2003 driven by the Ministry of Youth Affairs & Sports has attempted to focus on special requirements of youth, covering 13 to 35 years, further subdivided into 13-19 years and 20-35 years. The adapted strategies include youth empowerment, gender justice, inter-sectoral approach, and an information and research network. The priority target groups under the policy include rural and tribal youth, out-of-school youth, adolescents particularly females, youth with disabilities and adolescents under special circumstances like victims of trafficking; orphans and street children135. A number of State-specific policies and programmes also exist that highlight State strategies for meeting the needs of youth134. It is also apparent that the impact of these policies on health of youth has not been evaluated for its coverage, comprehensiveness, efficacy and effectiveness.

Conclusion

The present review, though limited in nature highlights that a significant proportion of youth has health impacting behaviours and conditions that affect their growth and development, that the problem is on the increase, many are interlinked and coexist, and likely to increase in the coming years. Some of the major health impacting behaviours and problems among the young people include undernutrition and overnutrition, common mental disorders including stress and anxiety, suicidal tendencies and increased suicidal death rates, increased consumption of tobacco, alcohol and other substance use, NCDs, high risk sexual behaviours including STIs and importantly, injuries mainly RTIs and violence. Many of these problems are closely linked to ongoing nutrition and epidemiological transition and are behaviour related with a life course perspective. There is a strong need for public health community to identify, prepare, integrate and implement activities that help to promote health and healthy lifestyles of young people and establish mechanisms for delivery of population-based interventions along with measuring its impact. There is a need to generate good quality and robust population data that can drive policies and programmes. Strategic investments in health, nutrition, education, employment and welfare are critical for healthy growth of young people and these programmes need to be monitored and evaluated for their efficacy and effectiveness using public health approaches.

References

- 1.Adolescent health and development. WHO Regional office for South-East Asia. [accessed on January 8, 2013]. Available from: http://www.searo.who.int/entity/child_adolescent/topics/adolescent_health/en/index.html .

- 2.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 1998. Life in the 21st Century. A vision for all. Report of the Director-General. Chapter 3. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [accessed on January 8, 2013]. Health across the life span; pp. 66–111. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/1998/en/whr98_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stang J, Story M. Chapter 1. Adolescent growth and development. Guidelines for adolescent nutrition services. Minneapolis, MN Center for Leadership, Education and Training in Maternal and Child Nutrition, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota. 2005. [accessed on June 20, 2012]. Available from: http://www.epi.umn.edu/let/pubs/img/adol_ch1.pdf .

- 4.Jekielek S, Brown B. Kids count/PRB/Child Trends Report on Census 2000. The Annie Casey Foundation, Population reference Bureau, and Child trends, Washington DC; 2005. May, [accessed on June 20, 2012]. The Transition to Adulthood: Characteristics of Young Adults Ages 18 to 24 in America. Available from: http://www.prb.org/pdf05/transitiontoadulthood.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 5.Planning commission. New Delhi: 2008. Sep, [accessed on June 18, 2012]. Report of the Steering committee on youth affairs and sports for the eleventh five year plan (2007-12) p. 41. Available from: http://planningcommission.nic.in/aboutus/committee/strgrp11/str_yas.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health Profile 2011. New Delhi: Prabhat Publicity; 2011. [accessed on June 18, 2012]. Central Bureau of Health Intelligence. Demographic indicators. Available from: http://www.cbhidghs.nic.in/writereaddata/mainlinkFile/01%20Cover%20page%202011.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dev SM, Venkatanarayana M. Mumbai: indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research; 2011. [accessed on December 28, 2012]. Youth employment and unemployment in India. Available from: http://www.igidr.ac.in/pdf/publication/WP-2011-009.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization; 2011. [accessed on June 8, 2013]. Young people: health risks and solutions. Fact sheet no. 345. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs345/en/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adolescent Health Services: Missing Opportunities. [accessed on January 8, 2013]. Available from: http://books.nap.edu/openbook.php?record_id=12063&page=1 .

- 10.Collins PY, Insel TR, Chockalingam A, Daar A, Maddox YT. Grand challenges in global mental health: integration in research, policy, and practice. PLoS Med. 2013;10:e1001434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gururaj G. Injury prevention and care: an important public health agenda for health, survival and safety of children. Indian J Pediatr. 2013;80(Suppl 1):S100–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-012-0783-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adolescent Health - Healthy People. [accessed on January 9, 2013]. Available from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/overview.aspx?topicid=2#Ref_03 .

- 13.Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, Adams SH, Irwin CE, Brindis CD. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. J Adolesc Health. 2009;45:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.New York: Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations; 2004. [accessed on January 9, 2013]. World Youth Report 2003: The Global Situation of Young People; p. 429. Available from: http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unyin/documents/worldyouthreport.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition; 2002. [accessed on July 12, 2012]. National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. Diet & nutritional status of rural population; p. 158. NNMB Technical Report No.21. Available from: http://www.nnmbindia.org/NNMBREPORT2001-web.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hyderabad: National Institute of Nutrition; 2006. [accessed on July 12, 2012]. National Nutrition Monitoring Bureau. Diet & nutritional status of population and prevalence of hypertension among adults in rural areas; p. 166. NNMB Technical Report No: 24. Available from: http://www.nnmbindia.org/NNMBReport06Nov20.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wasnik V, Rao BS, Rao D. A study of the health status of early adolescent girls residing in social welfare hostels in Vizianagaram district of Andhra Pradesh state, India. Inter J Collabor Res Intern Med Public Health [serial on the Internet] 2012. [accessed on July 18, 2012]. Available from: http://iomcworld.com/ijcrimph/ijcrimph-v04-n01-07.htm .

- 18.Rao VG, Aggrawal MC, Yadav R, Das SK, Sahare LK, Bondley MK, et al. Intestinal parasitic infections, anaemia and undernutrition among tribal adolescents of Madhya Pradesh. Indian J Community Med. 2003;28:26–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choudhary S, Mishra CP, Shukla KP. Nutritional status of adolescent girls in rural area of Varanasi. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2003;34:53–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haboubi GJ, Shaikh RB. A comparison of the nutritional status of adolescents from selected schools of South India and UAE : a cross-sectional study. Indian J Community Med. 2009;34:108–11. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.51230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Parasuraman S, Kishor S, Singh SK, Vaidehi Y. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), India, 2005-06. Mumbai: International Institute for Population Sciences. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ICF Macro; 2009. [accessed on August 4, 2012]. A profile of youth in India. Available from: http://www.rchiips.org/NFHS/youth_report_for_website_18sep09.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maliye C, Deshmukh P, Gupta S, Kaur S, Mehendale A, Garg B. Nutrient intake amongst rural adolescent girls of Wardha. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:400–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.69264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deshmukh PR, Gupta SS, Bharambe MS, Dongre AR, Maliye C, Kaur S, et al. Nutritional status of adolescents in rural Wardha. Indian J Pediatr. 2006;73:139–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02820204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adolescents in India: A profile. UN Inter Agency Working Group on Population and Development (IAWG-P&D) 2003. [accessed on January 10, 2013]. p. 90. Available from: http://web.unfpa.org/focus/india/facetoface/docs/adolescentsprofile.pdf .

- 25.Midha T, Nath B, Kumari R, Rao YK, Pandey U. Childhood obesity in India: a meta-analysis. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:945–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0587-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goyal JP, Kumar N, Parmar I, Shah VB, Patel B. Determinants of overweight and obesity in affluent adolescent in Surat city, South Gujarat region, India. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:296–300. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.91418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotian MS, Kumar SG, Kotian SS. Prevalence and determinants of overweight and obesity among adolescent school children of South Karnataka, India. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:176–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.62587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aggarwal T, Bhatia R, Singh D, Sobti PC. Prevalence of obesity and overweight in affluent adolescents from Ludhiana, Punjab. Indian Pediatr. 2008;45:500–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laxmaiah A, Nagalla B, Vijayaraghavan K, Nair M. Factors affecting prevalence of overweight among 12- to 17-year-old urban adolescents in Hyderabad, India. Obesity. 2007;15:1384–90. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehta M, Bhasin SK, Agrawal K, Dwivedi S. Obesity amongst affluent adolescent girls. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:619–22. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0109-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khadilkar VV, Khadilkar AV. Prevalence of obesity in affluent school boys in Pune. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:857–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kumar S, Mahabalaraju DK, Anuroopa MS. Prevalence of obesity and its influencing factor among affluent school children of Davangere city. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:15–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cherian AT, Cherian SS, Subbiah S. Prevalence of obesity and overweight in urban school children in Kerala, India. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:475–7. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jeemon P, Prabhakaran D, Mohan V, Thankappan KR, Joshi PP, Ahmed F. SSIP Investigators. Double burden of underweight and overweight among children (10-19 years of age) of employees working in Indian industrial units. Natl Med J India. 2009;22:172–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srihari G, Eilander A, Muthayya S, Kurpad AV, Seshadri S. Nutritional status of affluent Indian school children: what and how much do we know? Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:204–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mohan V, Sandeep S, Deepa R, Shah B, Varghese C. Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes: Indian scenario. Indian J Med Res. 2007;125:217–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shetty PS. Nutrition transition in India. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:175–82. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.High-Risk Sexual Behavior. EverydayHealth.com. [accessed on January 14, 2013]. Available from: http://www.everydayhealth.com/health-center/highrisk-sexual-behavior-info.aspx .

- 39.Mumbai: IIPS; [accessed on August 17, 2012]. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and Macro International, 2007. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-3), 2005-06, India: Key Findings. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/SR128/SR128.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar GA, Dandona R, Kumar SG, Dandona L. Behavioral surveillance of premarital sex among never married young adults in a high HIV prevalence district in India. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:228–35. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9757-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santhya KG, Ram U, Acharya R, Mohanty S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Singh A, et al. Pre-marital sexual relations among youth in India: findings from the youth in India, situations and needs study. Proceedings of the xxvi International Union for the Scientific Study of Population Conference 2009 Sept 27-Oct2; Marrakech, Morocoo [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alexander M, Garda L, Kanade S, Jejeebhoy S, Ganatra B. Correlates of premarital relationships among unmarried youth in Pune district, Maharashtra, India. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2007;33:150–9. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.33.150.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savithri R, Mehra S, Kole SK, Sakhuja A. New Delhi: MAMTA - Health Institute for Mother and Child; 2002. Sexual behaviour among adolescents and young people in India : some emerging trends. Working Paper Series No. 3. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sujay R. Health and Population Innovation, Fellowship Programme Working Paper No. 9. New Delhi: Population Council; 2009. [accessed on August 17, 2012]. Premarital sexual behaviour among unmarried college students of Gujarat, India; p. 51. Available from: http://www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/wp/India_HPIF/009.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaffey MF, Venkatesh S, Dhingra N, Khera A, Kumar R, Arora P, et al. Male use of female sex work in India: A Nationally Representative Behavioural Survey. PLoS One. 2011;6:e22704. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ghule M, Donta B. Correlates of sexual behaviour of rural college youth in Maharashtra, India. East J Med. 2011;16:122–32. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy VM, Chandrashekar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: a meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Gururaj G, Seshadri S, Subbakrishna DK, Bhola P, et al. Epidemiological study of child & adolescent psychiatric disorders in urban & rural areas of Bangalore, India. Indian J Med Res. 2005;122:67–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anita S, Gaur DR, Vohra AK, Subash S, Khurana H. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity among 6 to 14 years old children. Indian J Community Med. 2003;28:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pillai A, Patel V, Cardozo P, Goodman R, Weiss HA, Andrew G. Non-traditional lifestyles and prevalence of mental disorders in adolescents in Goa, India. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:45–51. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.034223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Malhotra S, Kohli A, Kapoor M, Pradhan B. Incidence of childhood psychiatric disorders in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:101–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.49449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nair MK, Paul MK, John R. Prevalence of depression among adolescents. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:523–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02724294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ahmad A, Khalique N, Khan Z, Amir A. Prevalence of psychosocial problems among school going male adolescents. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:219. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bansal V, Goyal S, Srivastava K. Study of prevalence of depression in adolescent students of a public school. Ind Psychiatry J. 2009;18:43–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-6748.57859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sahoo S, Khess CR. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress among young male adults in India: a dimensional and categorical diagnoses-based study. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:901–4. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181fe75dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deb S, Chatterjee P, Walsh KM. Anxiety among high school students in India : comparisons across gender, school type, social strata, and perceptions of quality time with parents [serial on the Internet] Aust J Educ Dev Psychol. 2010;10:18–31. [Google Scholar]

- 57.World Health Organization. 10 facts on adolescent health. [accessed on January 14, 2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/features/factfiles/adolescent_health/facts/en/index4.html .

- 58.Latha KS, Reddy H. Patterns of stress, coping styles and social supports among adolescents. J Indian Assoc Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2007;3:5–9. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghaderi AR, Kumar GV, Kumar S. Depression, anxiety and stress among the Indian and Iranian students. J Indian Acad Appl Psychol. 2009;35:33–7. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dubat K, Punia S, Goyal R. A study of life stress and coping styles among adolescent girls. J Soc Sci. 2007;14:191–4. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharma J, Sidhu R. Sources of stress among students preparing in coaching institutes for admission to professional courses. J Psychol. 2011;2:21–4. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suicide prevention (SUPRE). World Health Organization. [accessed on January 15, 2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mental_health/prevention/suicide/suicideprevent/en/

- 63.New Delhi: National Crime Records Bureau, Ministry of Home Affairs; 2012. [accessed on November 15, 2012]. Accidental deaths & suicides in India 2011; p. 317. Available from: http://ncrb.nic.in/CD-ADSI2011/ADSI-2011%20REPORT.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vijayakumar L. Suicide & mental disorders - a maze? Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:371–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel V, Ramasundarahettige C, Vijayakumar L, Thakur JS, Gajalakshmi V, Gururaj G, et al. Suicide mortality in India: a nationally representative survey. Lancet. 2012;379:2343–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60606-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Aaron R, Joseph A, Abraham S, Muliyil J, George K, Prasad J, et al. Suicides in young people in rural southern India. Lancet. 2004;363:1117–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15896-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gururaj G, Sateesh VL, Rayan AB, Roy AC, Amarnath, Ashok J, et al. Bengaluru injury surveillance collaborators group. Bengaluru: National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences; 2008. [accessed on January 16, 2013]. Bengaluru injury / Road traffic injury surveillance programme: a feasibility study. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/epidemiology/bisp/sr1.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prasad J, Abraham VJ, Minz S, Abraham S, Joseph A, Muliyil JP, et al. Rates and factors associated with suicide in Kaniyambadi Block, Tamil Nadu, South India, 2000-2002. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2006;52:65–71. doi: 10.1177/0020764006061253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Soman CR, Safraj S, Kutty VR, Vijayakumar K, Ajayan K. Suicide in South India: a community-based study in Kerala. Indian J Psychiatry. 2009;51:261–4. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.58290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Arun P, Chavan BS. Stress and suicidal ideas in adolescent students in Chandigarh. Indian J Med Sci. 2009;63:281–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharma R, Grover VL, Chaturvedi S. Suicidal behavior amongst adolescent students in south Delhi. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;5:30–3. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.39756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pal R, Tsering D. Tobacco use in Indian high-school students. Int J Green Pharm. 2009;3:319–23. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gajalakshmi V, Kanimozhi CV. A survey of 24,000 students aged 13-15 years in India: Global Youth Tobacco Survey 2006 and 2009. Tob Use Insights. 2010;3:23–31. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gururaj G, Girish N. Tobacco use amongst children in Karnataka. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:1095–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Narain R, Sardana S, Gupta S, Sehgal A. Age at initiation & prevalence of tobacco use among school children in Noida, India: A cross-sectional questionnaire based survey. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:300–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh V, Pal HR, Mehta M, Kapil U. Tobacco consumption and awareness of their health hazards amongst lower income group school children in National capital territory of Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 2007;44:293–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dhavan P, Stigler MH, Perry CL, Arora M, Reddy KS. Patterns of tobacco use and psychosocial risk factors among students in 6th through 10th grades in India: 2004-2006. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:807–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jindal SK, Aggarwal AN, Gupta D, Kashyap S, Chaudhary D. Prevalence of tobacco use among school going youth in North Indian States. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2005;47:161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mathur C, Stigler MH, Perry CL, Arora M, Reddy KS. Differences in prevalence of tobacco use among Indian urban youth: the role of socioeconomic status. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:109–16. doi: 10.1080/14622200701767779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Reddy KS, Perry CL, Stigler MH, Arora M. Differences in tobacco use among young people in urban India by sex, socioeconomic status, age, and school grade: assessment of baseline survey data. Lancet. 2006;367:589–94. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68225-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gururaj G, Murthy P, Rao GN, Benegal V. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences; 2011. [accessed on January 14, 2013]. Alcohol related harm: Implications for public health and policy in India; p. 160. Publication No.: 73. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/deaddiction/CAM/Alcohol_report_NIMHANS.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 82.The extent, patterns and trends of drug abuse in India - National Survey. UNODC, Regional Office for South Asia. 2002. Available from: http://www.unodc.org/pdf/india/publications/national_Survey/10_results.pdf . accessed on January 15, 2013.

- 83.New Delhi: 2006. [accessed on January 14, 2013]. Health System Performance Assessment. World Health Survey, 2003, India. International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva and WHO - India-WR Office. Available from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/whs_hspa_book.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chaturvedi HK, Mahanta J. Sociocultural diversity and substance use pattern in Arunachal Pradesh, India. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Girish N, Kavita R, Gururaj G, Benegal V. Alcohol use and implications for public health: patterns of use in four communities. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:238–44. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ningombam S, Hutin Y, Murhekar MV. Prevalence and pattern of substance use among the higher secondary school students of Imphal, Manipur, India. Natl Med J India. 2011;24:11–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Medhi GK, Hazarika NC, Mahanta J. Correlates of alcohol consumption and tobacco use among tea industry workers of Assam. Subst Use Misuse. 2006;41:691–706. doi: 10.1080/10826080500411429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Pagare D, Meena GS, Singh MM, Saha R. Risk factors of substance use among street children from Delhi. Indian Pediatr. 2004;41:221–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kangule D, Darbastwar M, Kokiwar P. A cross-sectional study of prevalence of substance use and its determinants among male tribal youths. Int J Pharm Biomed Sci. 2011;2:61–4. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tsering D, Pal R, Dasgupta A. Licit and illicit substance use by adolescent students in eastern India: prevalence and associated risk factors. J Neurosci Rural Pract. 2010;1:76–81. doi: 10.4103/0976-3147.71721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rai D, Gaete J, Girotra S, Pal HR, Araya R. Substance use among medical students: time to reignite the debate? Natl Med J India. 2008;21:75–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bal B, Mitra R, Mallick AH, Chakraborti S, Sarkar K. Nontobacco substance use, sexual abuse, HIV, and sexually transmitted infection among street children in Kolkata, India. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45:1668–82. doi: 10.3109/10826081003674856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sarangi L, Acharya HP, Panigrahi OP. Substance abuse among adolescents in urban slums of Sambalpur. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:265–7. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.43236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Juyal R, Bansal R, Kishore S, Negi KS, Chandra R, Semwal J. Substance use among intercollege students in district Dehradun. Indian J Community Med. 2006;31:252–4. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aceijas C, Friedman SR, Cooper HL, Wiessing L, Stimson GV, Hickman M. Estimates of injecting drug users at the national and local level in developing and transitional countries, and gender and age distribution. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82(Suppl 3):iii10–iii17. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.019471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Narayanappa D, Rajani HS, Mahendrappa KB, Ravikumar VG. Prevalence of prehypertension and hypertension among urban and rural school going children. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:755–6. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0159-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kumar J, Deshmukh PR, Garg BS. Prevalence and correlates of sustained hypertension in adolescents of Rural Wardha, Central India. Indian J Pediatr. 2012;79:1206–12. doi: 10.1007/s12098-011-0663-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sharma A, Grover N, Kaushik S, Bhardwaj R, Sankhyan N. Prevalence of hypertension among schoolchildren in Shimla. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:873–6. doi: 10.1007/s13312-010-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Non-Communicable diseases and adolescents- an opportunity for action. The AstraZeneca. [accessed on May 20, 2013]. Available from: http://www.jhsph.edu/research/centers-and-institutes/center-for-adolescenthealth/az/noncommunicable.pdf .

- 100.Raj M. Essential hypertension in adolescents and children: recent advances in causative mechanisms. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;15(Suppl 4):S367–73. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.86981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mohan V, Deepa M, Deepa R, Shanthirani CS, Farooq S, Ganesan A, et al. Secular trends in the prevalence of diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance in urban South India-the Chennai Urban Rural Epidemiology Study (CURES-17) Diabetologia. 2006;49:1175–8. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Misra A, Vikram NK, Arya S, Pandey RM, Dhingra V, Chatterjee A, et al. High prevalence of insulin resistance in postpubertal Asian Indian children is associated with adverse truncal body fat patterning, abdominal adiposity and excess body fat. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004;28:1217–26. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sharma BS, Kumar MG, Chandel R. Prevalence of asthma in urban school children in Jaipur, Rajasthan. Indian Pediatr. 2012;49:835–6. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0188-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dhabadi BB, Athavale A, Meundi A, Rekha R, Suruliraman M, Shreeranga A, et al. Prevalence of asthma and associated factors among school children in rural South India. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:120–5. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jagnoor J, Suraweera W, Keay L, Ivers RQ, Thakur JS, Jha P Million Death Study Collaborators. Unintentional injury mortality in India, 2005: Nationally representative mortality survey of 1.1 million homes. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:487. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.New Delhi: Transport Research Wing, Ministry of Road Transport and Highways, Government of India; 2012. [accessed on January 14, 2013]. Road accidents in India 2011; p. 67. Available from: http://morth.nic.in/showfile.asp?lid=835 . [Google Scholar]

- 107.New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General, India. Ministry of Home Affairs; 2009. [accessed on January 14, 2013]. Report on causes of death in India 2001-2003; p. 84. Available from: http://www.cghr.org/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/Causes_of_death_2001-03.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 108.Aeron Thomas A, Jacobs GD, Sexton B, Gururaj G, Rahman F. United Kingdom: Report No. PR/INT/2TS 2004. Transport Research Laboratory; 2004. The involvement and impact of road crashes on the poor: and India, Bangladesh case studies; p. 34. [Google Scholar]

- 109.Gururaj G Bangalore Road Safety and Injury Prevention Program Collaborators Group. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences; 2011. [accessed on September 14, 2012]. Bangalore road safety and injury prevention program: results and learning, 2007 - 2010; p. 23. Publication No. 81. Available from: http://www.nimhans.kar.nic.in/epidemiology/bisp/brsipp2011a.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sharma B, Singh VP, Sharma R, Sumedha Unnatural deaths in Northern India: a profile. J Indian Acad Forensic Med. 2004;26:140–6. [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dandona R, Kumar GA, Ameratunga S, Dandona L. Road use pattern and risk factors for non-fatal road traffic injuries among children in urban India. Injury. 2011;42:97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dandona R, Kumar GA, Ameer MA, Ahmed GM, Dandona L. Incidence and burden of road traffic injuries in urban India. Inj Prev. 2008;14:354–9. doi: 10.1136/ip.2008.019620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Violence. World Health Organization. [accessed on January 15, 2013]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/violence/en/

- 114.World Health Organization; [accessed on August 4, 2013]. Youth violence and alcohol fact sheet. Available from: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/factsheets/ft_youth.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sarkar M. A study on domestic violence against adult and adolescent females in a rural area of West Bengal. Indian J Community Med. 2010;35:311–5. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.66881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ackerson LK, Subramanian SV. Domestic violence and chronic malnutrition among women and children in India. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1188–96. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Acharya R, Ram F, Jejeebhoy SJ, Singh A, Santhya K, Ram U, et al. Physical and sexual violence within marriage among youth in India: findings from the youth in India, situation and needs study 2009. [accessed on August 21, 2012]. Available from: http://iussp2009.princeton.edu/papers/93402 .

- 118.Deb S, Modak S. Prevalence of violence against children in families in Tripura and its relationship with socio-economic factors. J Inj Violence Res. 2010;2:5–18. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v2i1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Baruah A, Baruha A. Epidemiological study of violence: a study from North East India. Indian J Community Med. 2007;32:137–8. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Munni R, Malhi P. Adolescent violence exposure, gender issues and impact. Indian Pediatr. 2006;43:607–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sharma R, Grover VL, Chaturvedi S. Risk behaviors related to inter-personal violence among school and college-going adolescents in south Delhi. Indian J Community Med. 2008;33:85–8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.40874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Gururaj G, Isaac MK, Girish N, Subbakrishna DK. Bangalore: National Institute of Mental Health & Neuro Sciences; 2004. Final report of the pilot study establishing health behaviours surveillance in respect of mental health. Report No.: WR/IND HSD 001/G – SE/02/413814; p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pandey A, Mishra RM, Reddy DC, Thomas M, Sahu D, Bharadwaj D. Alcohol use and STI among men in India: evidences from a national household survey. Indian J Community Med. 2012;37:95–100. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.96094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Child welfare. Ministry of Women and Child Development, Government of India. [accessed on January 15, 2013]. Available from: http://wcd.nic.in/cwnew.htm .

- 125.New Delhi: Department of Education, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India; 1998. [accessed on January 15, 2013]. National policy on Education, 1986 (as modified in 1992) with National Policy on education 1968. Available from: http://mhrd.gov.in/sites/upload_files/mhrd/files/NPE86-mod92.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan. Programme for universalization of elementary education. Department of School Education & Literacy, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. [accessed on January 22, 2013]. Available from: http://ssa.nic.in/whoswho/department-of-school-education-Literacy-ministry-of-hrd .

- 127.Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan. Department of School Education & Literacy, Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. [accessed on January 22, 2013]. Available from: http://mhrd.gov.in/rashtriya_madhyamik_shiksha_abhiyan .

- 128.National policy for the empowerment of women (2001). Ministry of Women & Child Development, Government of India. [accessed on January 22, 2013]. Available from: www.wcd.nic.in/empwomen.htm .

- 129.Guidelines for the Balika Samriddhi Yojana (BSY) (Recast Scheme). Ministry of Women & Child Development, Government of India. [accessed on January 22, 2013]. Available from: http://wcd.nic.in/BSY.htm .

- 130.Scheme of National child labour project revised-2003. Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India. [accessed on September 17, 2013]. Available from: http://labour.gov.in/upload/uploadfiles/files/schemes/Scheme%20of%20National%20Child%20Labour%20Project%20Revised.pdf .

- 131.Revised guidelines. Special projects for placement linked skill development of rural youths under Aajeevika (NRLM). Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India. [accessed on January 22, 2013]. Available from: http://rural.nic.in/sites/downloads/programmes-schemes/SGSY_SpecialProjectsGuidelines.pdf .

- 132.National policy for persons with disabilities (Page 9) - Acts/Rules & Regulations/Policies/Guidelines/Codes/Circulars/ Notifications - Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India. [accessed on January 22, 2013]. Available from: http://socialjustice.nic.in/nppde.php?pageid=9 .

- 133.Implementation guide on RCH II Adolescent Reproductive Sexual Health strategy: for state and district programme managers. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2006. [accessed on January 16, 2012]. Available from: www.nrhmhp.gov.in/sites/default/files/files/ARSH-guidelines(1).pdf .

- 134.International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS), Population Council. Mumbai: IIPS; 2010. [accessed on September 16, 2012]. Youth in India: situation and needs 2006- 2007; p. 396. Available from: http://www.iipsindia.org/pdf/India%20Report.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 135.National Youth Policy 2003. Department of Youth Affairs. Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports, Government of India. [accessed on January 16, 2013]. Available from: http://yas.nic.in/index2.aspb?linkid=47&slid=70&sublinkid=32&langid=1 .