Abstract

Group II nucleopolyhedroviruses (NPVs), e.g., Spodoptera exigua MNPV, lack a GP64-like protein that is present in group I NPVs but have an unrelated envelope fusion protein named F. In contrast to GP64, the F protein has to be activated by a posttranslational cleavage mechanism to become fusogenic. In several vertebrate viral fusion proteins, the cleavage activation generates a new N terminus which forms the so-called fusion peptide. This fusion peptide inserts in the cellular membrane, thereby facilitating apposition of the viral and cellular membrane upon sequential conformational changes of the fusion protein. A similar peptide has been identified in NPV F proteins at the N terminus of the large membrane-anchored subunit F1. The role of individual amino acids in this putative fusion peptide on viral infectivity and propagation was studied by mutagenesis. Mutant F proteins with single amino acid changes as well as an F protein with a deleted putative fusion peptide were introduced in gp64-null Autographa californica MNPV budded viruses (BVs). None of the mutations analyzed had an major effect on the processing and incorporation of F proteins in the envelope of BVs. Only two mutants, one with a substitution for a hydrophobic residue (F152R) and one with a deleted putative fusion peptide, were completely unable to rescue the gp64-null mutant. Several nonconservative substitutions for other hydrophobic residues and the conserved lysine residue had only an effect on viral infectivity. In contrast to what was expected from vertebrate virus fusion peptides, alanine substitutions for glycines did not show any effect.

The members of the Baculoviridae family are large, enveloped, double-stranded DNA viruses that are exclusively pathogenic for arthropods, predominantly insects of the order Lepidoptera (1). Baculoviruses are classified into two genera, Nucleopolyhedrovirus (NPV) and Granulovirus (GV). The NPVs can be phylogenetically subdivided into group I and II NPVs (6, 10, 12, 13). The budded virus (BV) phenotype of group I NPVs contains a GP64-like major envelope glycoprotein. This protein is involved in viral attachment to host cells (11), triggers low-pH-dependent membrane fusion during BV entry by endocytosis (4, 20, 35, 42), and is required for efficient budding from the cell surface (27, 29).

In contrast, BVs of group II NPVs and GVs lack a homolog of GP64. The low-pH-dependent membrane fusion during BV entry by endocytosis is triggered in this case by a so-called F protein (17, 32). F homologs are also found as envelope proteins of the insect errantiviruses while cellular homologs are found in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and in the African malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae (25, 36). Unlike GP64, the F proteins are structurally similar to fusion proteins from several vertebrate viruses such as orthomyxoviruses and paramyxoviruses. Recently, it has been shown that the GP64 protein in BVs of Autographa californica MNPV (AcMNPV) can be replaced by the F protein of group II NPVs (24), implying that F is functionally analogous to GP64.

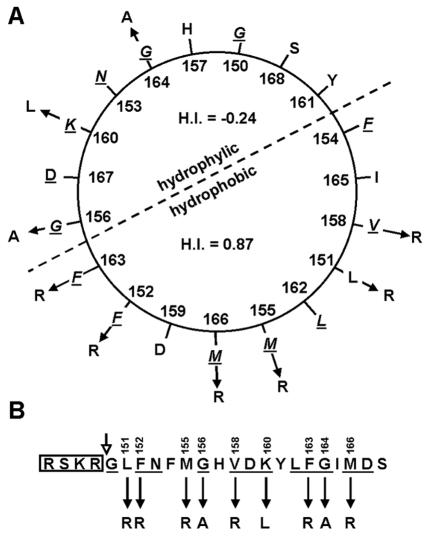

Like several mammalian viral envelope fusion proteins, the baculovirus F protein has to be posttranslationally cleaved by a proprotein convertase (furin) to become fusogenic (43). Also, for some errantiviruses it has been shown that the envelope protein is posttranslationally cleaved (31, 38, 39). Cleavage seems to be a general mechanism for viruses to activate their fusion proteins (21). In a number of virus families this cleavage occurs in front of a strongly hydrophobic sequence, the so-called fusion peptide (44, 45). These fusion peptides are believed to translocate upon cleavage to the top of the protein and to insert into the target membrane after exposure to low pH or receptor binding. This translocation facilitates the apposition of viral and cellular membranes upon further conformational changes of the fusion protein (21). Comparison of available F protein sequences reveals a conserved strongly hydrophobic domain with the consensus sequence ΦGXΦBΦΦGXKΦΦΦGXΦDXXDXXXΦ, where Φ represents hydrophobic amino acids, B stands for an aspartic acid or an asparagine residue, and X represents any amino acid (Fig. 1). This domain is preceded by a furin-like cleavage site in the F proteins from group II NPVs, GVs, and errantiviruses, whereas this domain is more or less absent in the remnant F protein from group I NPVs and in the cellular homologs (36). This strongly hydrophobic sequence at the N terminus of the membrane-anchored Spodoptera exigua MNPV (SeMNPV) F1 fragment has all the characteristics of a fusion peptide (45). It is well conserved within the virus family (Fig. 1), when modeled in α-helix, it displays one face with a hydrophobic index (H.I.) of about 0.9, according to the normalized consensus scale of Eisenberg (8), and a back face with hydrogen bonding potential, and it contains glycines on one side of the helix (Fig. 2A).

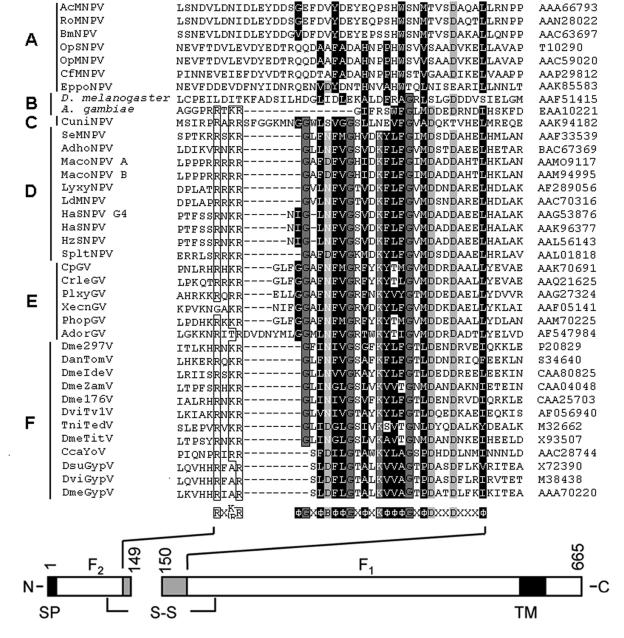

FIG. 1.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the SeMPNV F protein domains near the protease cleavage site with the corresponding domain of the F proteins of group I NPVs (A), dipterans (B), lepidopteran NPVs (C), group II NPVs (D), GVs (E), and errantiviruses (F). Virus and dipteran abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers of the F proteins are shown on the left and right, respectively. The conserved amino acids are boxed. The consensus sequence is shown below the alignment, in which B represents D or N, Φ indicates a hydrophobic amino acid (H.I., ≥0.12), and X represents any amino acid. A schematic presentation of the SeMNPV F protein, with the consensus sequence shown in gray boxes, is shown at the bottom. N, N terminus; C, C terminus; SP, signal peptide; TM, transmembrane domain; S-S, disulfide bridge.

FIG. 2.

(A) Helical wheel presentation of the first 21 N-terminal amino acids of the SeMNPV F1 fragment. The helix is typically amphipathic, with relatively polar amino acids (H.I., ≤0.48) above the dotted line, with an average H.I. of −0.24, and except for one aspartic acid residue (D), nonpolar amino acids (H.I., >0.62) below the dotted line, with an average H.I. of 0.87. (B) Linear presentation of the first 21 N-terminal amino acids of the SeMNPV F1 fragment preceded by the consensus furin recognition sequence (box). The open arrow indicates the cleavage site. Underlined amino acids are conserved as shown in Fig. 1. Solid arrows indicate the point mutations as well as the substitutions described in this study.

The role in the fusion process of the three conserved charged amino acids in the putative fusion peptide, immediately downstream of the proprotein convertase cleavage site, of the Lymantria dispar MNPV (LdMNPV) F protein has already been studied by site-directed mutagenesis (33). In this study, site-directed mutagenesis was used to investigate the role in viral propagation and infectivity of the conserved glycines and lysine as well as the hydrophobic amino acids in the putative fusion peptide of the SeMNPV F protein. Several conservative and nonconservative substitutions were introduced in the fusion domain, and their impact on virus propagation and infectivity was examined by using a recently developed AcMNPV pseudotyping system in which the envelope fusion protein GP64 can be replaced by the heterologous envelope fusion protein F of SeMNPV (24). The virus propagation of mutant infectious viruses as well as the amount of BV produced gives further credence for the role of the conserved domain of the baculovirus F protein as the fusion peptide.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells.

Spodoptera friguperda cell lines IPLB-Sf21 (41) and Sf9Op1D (35) (provided by G. W. Blissard, Ithaca, N.Y.) were cultured at 27°C in plastic culture flasks (Nunc) in Grace's insect medium, pH 5.9 to 6.1 (Gibco-BRL), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Donor plasmids containing envelope protein genes.

A silent mutation was introduced into the coding sequence of the SeMNPV F open reading frame to generate an NdeI cloning site. Therefore, nucleotide 525 in the f open reading frame was changed from C to T by PCR-based site-directed mutation, according to the method of Sharrocks and Shaw (37). The 5′ mutagenic primer 5′-CGACGCTCACGAACTGCATATGCTCGCCAACACCACAA-3′ (underlined and boldface sequences represent an NdeI site and the mutation, respectively) and the 3′ primer 5′-GAGAGGCACGGGCCACGAAAGG-3′ (primer downstream of the PmeI site) were used in conjunction with plasmid pΔFBgusSe8 (24) as a template with Pfu polymerase (Promega). The PCR product (346 bp) was agarose gel purified, and the single strand containing the mutation at the 3′ end served as a 3′ mutagenic primer in a second PCR with 5′ primer 5′-TTATGGATCCATGCTGCGTTTTAAAGTGAT-3′ (the underlined sequence represents a BamHI site) with high-fidelity Expand long-template polymerase (Roche). The second PCR product (862 bp) was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega) to generate the intermediate plasmid pGEM-SeFNdeI. Plasmid pΔFBgusSeFNdeI was obtained by swapping the BamHI/PmeI fragment of pGEM-SeFNdeI with the same fragment of pΔFBgusSe8.

Mutations and deletions in the coding sequence of SeF, encompassing amino acids 151 to 170 were performed as follows. For every mutant, a 5′ phosphorylated primer pair (Table 1) was used with pGEM-SeFNdeI as a template and Pfu polymerase (Promega) to amplify the entire vector. Finally, the 5′ ends of the PCR products were ligated to its own 3′ ends, generating a new restriction endonuclease site at the junction (Table 1). Clones containing the additional restriction site were sequenced to confirm the mutation. The obtained mutations in pGEM-SeFNdeI were introduced into pΔFBgusSeFNdeI by swapping the BamHI/NdeI fragments.

TABLE 1.

Primer pairs generating the desired mutation and a restriction endonuclease sitea

| Mutant | 5′ primer (5′-3′) | 3′ primer (5′-3′) | REb site |

|---|---|---|---|

| SeFΔ151-170 | GCCCACGAACTGCATATGCTCGCC | GCCGCGTTTAGAGCGTCTTTTCG | NarI |

| SeFL151R | CCGCTTTAATTTTATGGGACACGTCG | CCGCGTTTAGAGCGTCTTTTC | NotI |

| SeFF152R | CCTTCGTAATTTTATGGGACACGTCG | CCTCGTTTAGAGCGTCTTTTCGTC | StuI |

| SeFM155R | GCGGACACGTCGACAAATATCTG | GGAAATTAAAAAGGCCGCGTTTAG | SacII |

| SeFG156A | CGTGGACAAATATCTGTTTGGCATTATG | TGTGCCATAAAATTAAAAAGGCCGCGTTT | Eco72I |

| SeFV158R | CGACAAATATCTGTTTGGCATTATG | CGATGTCCCATAAAATTAAAAAGGCCGCGTTT | NruI |

| SeFK160L | TCTATATCTGTTTGGCATTATGGACAG | TCTACGTGTCCCATAAAATTAAAAAGG | BglII |

| SeFF163K | CTTGCGTGGCATTATGGACAGCGAC | TACTTGTCGACGTGTCCCATAAAA | ScaI |

| SeFG164A | CGATTATGGACAGCGACGACGCTCAC | CGAACAGATATTTGTCGACGTG | NruI |

| SeFM166R | CGCGACAGCGACGACGCTCACGA | AATGCCAAACAGATATTTGTCGAC | NruI |

Underlined sequences of primer pairs generate restriction sites after blunt-ended self-ligation of PCR products. Mutations are indicated in boldface type.

RE, restriction endonuclease.

Transfection infection assay.

The gus reporter gene controlled by the p6.9 promoter and the mutant SeMNPV f genes under control of the gp64 promoter from pΔFBgusSeFNdeI were transposed into the att Tn7 transposon integrase site of a gp64-null AcMNPV bacmid (provided by G. W. Blissard) (24) according to the Bac-to-Bac manual (Invitrogen). Transpositions of inserts from donor plasmids were confirmed by PCR with a primer corresponding to the gentamicin resistance gene of the donor plasmid (P-gen-RV [5′-AGCCACCTACTCCCAACATC-3′]) in combination with a primer corresponding to the bacmid sequence adjacent to the transposition site (M13/pUC forward primer [5′-CCCAGTCACGACGTTGTAAAACG-3′]). Bacmid DNA, positive in the PCR, was electroporated into DH10β cells to eliminate the helper plasmid and some residual untransposed bacmid DNA.

Approximately 1 μg of DNA of each recombinant bacmid was transfected into 1.5 × 106 Sf21 or Sf9Op1D cells with 10 μl of Cellfectin (Invitrogen). At 5 days posttransfection, transfected cells were stained for GUS activity according to the Bac-to-Bac protocol (Invitrogen) to monitor transfection efficiency. The supernatant was clarified for 10 min at 2,200 × g and subsequently filter sterilized (0.45-μm pore size). One-fourth (500 μl) of the supernatant was used to infect 2.0 × 106 Sf9 or Sf9Op1D cells, respectively. At 72 h postinfection, cells were split into two portions. Cells of one portion were stained for GUS activity; the other portion was used at 10 days postinfection to monitor viral propagation. The gp64-positive bacmid served as a positive control for transfection and infection while the gp64-null bacmid was used as a negative control for transfection and infection (24). The SeFR149K bacmid was used as a negative control for F protein cleavage (24).

BV amplification and preparation.

Viruses carrying f genes that rescued the gp64-null phenotype were amplified by infecting 1.0 × 107 Sf21 cells with 500 μl of cell supernatant from 10 days postinfection. Viruses carrying f genes that did not rescue the gp64 deletion in Sf21 cells were amplified in a similar manner by using Sf9Op1D cells. Cells were split every 3 to 5 days until all cells were infected. Amplified pseudotyped viruses were titrated on Sf9Op1D cells by a 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) assay (30) and scored for infection by examining cells for GUS expression.

The genotypes of the pseudotyped viruses were confirmed by PCR on purified BV DNA by using primers P-SeF-mutant-FW (5′-GGCGTTGACGGTCGAGGCTAAAT-3′) and P-SeF-mutant-RV (5′-GTGCATCGCTTTTTCGGTGAGAGG-3′) to amplify a DNA fragment containing the incorporated restriction site (Table 1). The amplified DNA fragment was subsequently subjected to restriction enzyme analysis.

One-step growth experiments.

To monitor infectious BV production from viruses carrying mutant f genes that rescued the gp64-null phenotype, viral growth results were generated by collecting infected cell supernatants. Sf21 cells (1.5 × 105 cells per well, 24-well plates) were infected at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 5.0 or 0.5 TCID50 U/cell for 1 h at 27°C. After infection, the inoculum was removed and 0.5 ml of fresh medium was added to the cells. At 0, 24, 48, 72, 69, and 144 h postinfection, the infected cell supernatants were collected. For each time point postinfection and each virus sample, duplicate samples were generated. The quantity of infectious BVs in the samples was determined by TCID50 assays on Sf9Op1D cells. A third sample was generated for those duplicated samples for which titers differed by a factor of 2.5 or more.

Western blot analysis.

BVs were amplified by infecting 1.0 × 107 Sf21 or Sf9Op1D cells at an MOI of 0.5 TCID50 U/cell. Cells were split every 3 to 5 days until all cells were infected. BVs were purified from the supernatants as described previously (43). Equal amounts of BVs, determined by the Bradford method (5), were disrupted in Laemmli buffer (125 mM Tris-HCl, 2% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 5% 2-mercaptoethanol, 10% glycerol, 0.001% bromophenol blue [pH 6.8]) and denatured for 10 min at 95°C. Proteins were electrophoresed in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto Immobilon-P membranes (Millipore) by semidry electrophoresis transfer (3). Membranes were blocked overnight at 4°C in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 2% milk powder, followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature with either polyclonal antibodies anti-F1 and anti-F2 (43), monoclonal antibody AcV5 (14), or polyclonal antibody anti-VP39 (40) (provided by A. L. Passarelli, Manhattan, Kans.), all at a 1:1,000 dilution in PBS containing 0.2% milk powder. After washing three times for 15 min in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, the membranes were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated appropriate secondary antibody (Sigma, DAKO) in PBS containing 0.2% milk powder. After washing three times for 15 min in PBS containing 0.1% Tween-20, the signal was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence technology as described by the manufacturer (Amersham).

Computer-assisted analysis.

Protein comparisons with entries in the updated GenBank and EMBL were performed with the FASTA and BLAST programs (2, 34). Sequence alignments were performed with the program ClustalW (EMBL European Bioinformatics Institute, http://www.ebi.ac.uk) and edited with the Genedoc Software (28). The α-helix predictions were performed with the Protean software of DNASTAR by using the method of Garnier et al. (9).

RESULTS

Pseudotyping gp64-null AcMNPV with f mutants.

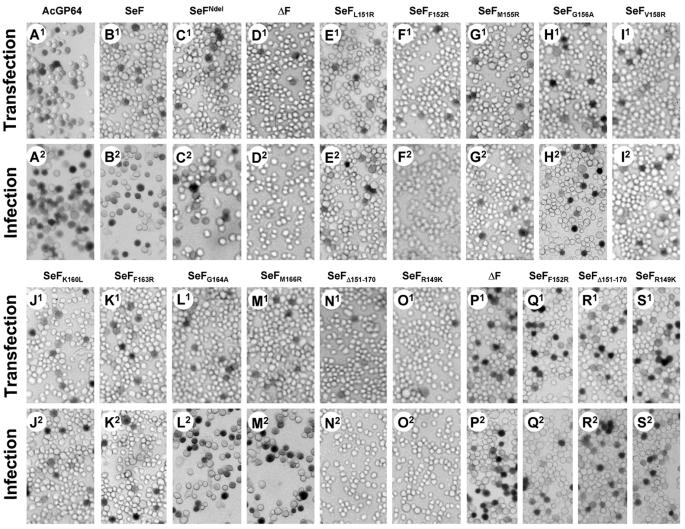

To examine the role of the N terminus of the SeMNPV F1 fragment in viral propagation and infectivity, mutational analysis on this domain was performed. The hydrophilic arginine was substituted for hydrophobic amino acids (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Five of these hydrophobic amino acids (F152, M155, V158, F163, and M166) are conserved and one (L151) is nonconserved among F homologs of group II NPVs, GVs, and errantiviruses (Fig. 1). Alanine was substituted for glycines (G156 and G164), and a hydrophobic leucine was substituted for the conserved lysine (K160). Each mutation was marked by the presence of a new restriction site. Furthermore, an F mutant with a deletion in the conserved region (amino acids 151 to 170) of the fusion peptide was also constructed. It was then determined whether the F protein mutants could rescue BV propagation of a gp64-null AcMNPV bacmid relative to the native F protein (24) when transfected into Sf21 cells. Mutant f genes under control of the AcMNPV gp64 promoter and a gus reporter gene downstream of the baculovirus p6.9 promoter were inserted simultaneously by Tn7-based transposition (23) into the gp64-null AcMNPV bacmid. Sf21 cells were transfected with the constructed bacmids together with various control bacmids: gp64-null AcMNPV bacmids containing (i) no envelope fusion protein gene (ΔF) (negative control), (ii) AcMNPV gp64 (positive control), (iii) SeMNPV f, (iv) SeMNPV fNdeI (f gene with silent mutation creating an NdeI cloning site), and (v) SeMNPV fK149R (f gene mutant negative in F0 cleavage). At 5 days posttransfection, cells were stained for GUS activity (Fig. 3A1 to O1). The presence of infectious BVs in the supernatant was determined by passaging the supernatants to new Sf21 cells. At 3 days postinfection, infected cells were demonstrated by their GUS activity (Fig. 3A2 to O2). The bacmids SeFL151R, SeFM155R, SeFG156A, SeFF152R, SeFV158R, SeFK160L, SeFF163R, SeFG164A, and SeFM166R were all able to produce infectious viruses (Fig. 3E to M), as were SeFNdeI (Fig. 3C) and the positive controls, AcGP64 and SeF (Fig. 3A and B). The bacmids SeFF152R and SeFΔ151-170 (Fig. 3F and N) and both negative controls (ΔF and SeFK149R) (Fig. 3D and O) were not able to produce infectious viruses, as expected. However, when those bacmids were transfected into Sf9Op1D cells, which constitutively express the Orgyia pseudogata MNPV GP64 protein to pseudotype AcMNPV (35), infectious BVs could be demonstrated (Fig. 3P to S), indicating that the defect in BV propagation was attributable to the expression of an inactive fusion protein.

FIG. 3.

Transfection-infection assays for viral propagation. Sf21 cells were transfected with indicated mutant gp64-null bacmids pseudotyped with f genes, incubated for 5 days, and stained for GUS activity (A1 to O1). Supernatants from the transfected cells were used to infect Sf21 cells (A2 to O2), which were incubated for 72 h and subsequently stained for GUS activity. Stained cells (infected cells) indicate that infectious virions were generated in the transfected cells. Bacmids that failed to propagate an infection in Sf21 cells (D2, F2, N2, and O2) were propagated in cells expressing constitutive O. pseudogata MNPV GP64 (Sf9Op1D). Sf9Op1D cells were transfected with indicated gp64-null bacmids (P1 to S1) and incubated for 5 days; then supernatants were transferred to Sf9Op1D and stained for GUS activity after 72 h (P2 to S2). Indicated gp64-null AcMNPV bacmids are pseudotyped with AcGP64 (AcMNPV gp64), SeF (SeMNPV f), SeFNdeI (SeMNPV f with silent mutation generating an NdeI restriction site), ΔF (no envelope fusion gene), SeFL151R, SeFF152R, SeFM155R, SeFG156A, SeFV158R, SeFK160L, SeFF163R, SeFG164A, SeFM166R (SeMNPV f with mutations causing amino acid substitution in the putative fusion peptide as indicated in the subscript), SeFΔ151-170 (SeMNPV f with a deletion of the segment encoding amino acids 151 to 170), and SeFR149K (SeMNPV f with mutations causing an amino acid substitution in the furin cleavage site).

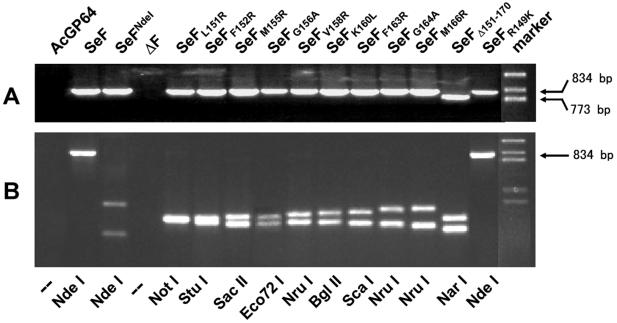

BVs carrying an envelope fusion protein gene that rescued the gp64-null phenotype were amplified by infecting Sf21 cells; those BVs that were not rescued were amplified by using Sf9Op1D cells as described in Materials and Methods. The amplified viruses were all subjected to PCR analysis to verify the introduced mutations in their f genes (Fig. 4). For viruses containing the mutant f genes, PCR fragments of similar sizes were obtained, whereas the SeFΔ151-170 mutant showed a much smaller fragment (Fig. 4A). Along with the desired mutations, an additional restriction site was introduced into the f genes to mark the mutation (Table 1), allowing the analysis of the resulting PCR fragments by restriction enzyme analysis (Fig. 4B). From the patterns, it could be concluded that the gp64-null AcMNPV viruses contained the correct mutations.

FIG. 4.

PCR and restriction enzyme analyses of purified BV DNA to verify the genotype of indicated pseudotyped vAcGP64− viruses as described in the legend to Fig. 3. (A) PCR with f gene-specific primer pairs used to examine mutant viral DNAs amplifying an 834-bp fragment, when the virus contains the f gene, except for SeFΔ151-170, where a 773-bp fragment was amplified. (B) Restriction enzyme analysis of PCR-amplified DNA fragments. Mutant F genes have, in addition to the incorporated NdeI site, an additional restriction site, which is used to distinguish the viruses (Table 1). The SeFR149K mutant has neither a NdeI site nor an additional restriction site.

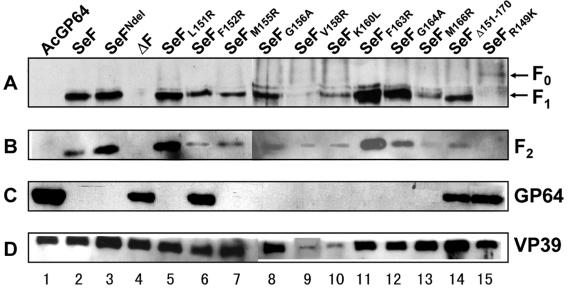

Western analysis of f gene-pseudotyped gp64-null AcMNPV viruses.

The effect of the various mutations on the processing and incorporation of the F protein in BVs was determined by Western analysis (Fig. 5). An antibody against the major nucleocapsid protein (anti-VP39) served as an internal control to determine the amount of BVs used in the analysis. Results indicated that all mutant F proteins were present in BVs. The amounts of BVs for each recombinant virus were estimated to be similar, except for SeFV158R (lane 9) and SeFK160L (lane 10), where less BVs were used (Fig. 5D). The AcMNPV GP64 protein could be detected with the repair virus (Fig. 5C, lane 1) as well as for the viruses propagated in Sf9Op1D cells (Fig. 5C, lanes 4, 6, 14, and 15). Western analysis with antibodies against the SeMNPV F1 and F2 indicated that the incorporation of the F protein in the BVs was reduced for SeFF152R, SeFM155R, SeFM166R, and SeFR149K (Fig. 5A and B, lanes 6, 7, 13, and 15, respectively) compared to that of native SeF protein (Fig. 5A and B, lanes 1). Furthermore, all mutant F proteins, except SeFR149K (Fig. 5A, lane 15), lacking a furin cleavage site, were properly cleaved into F1 (Fig. 5A) and F2 (Fig. 5B) fragments.

FIG. 5.

Western blot analysis of gp64-null BVs pseudotyped with indicated (mutant) f genes as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Infectious BVs were generated in Sf21 cells (lanes 1 to 3, 5, 6, and 8 to 13), and BVs, which are not able to propagate in Sf21 cells, were propagated in Sf9Op1D cells (lanes 4, 7, 14, and 15). Blots were probed with antibodies anti-F1 (A), anti-F2 (43) (B), and anti-GP64 (monoclonal antibody AcV5) (14) (C). (D) An anti-nucleocapsid antibody (anti-VP39) was used as an internal control for each preparation of purified BVs (40).

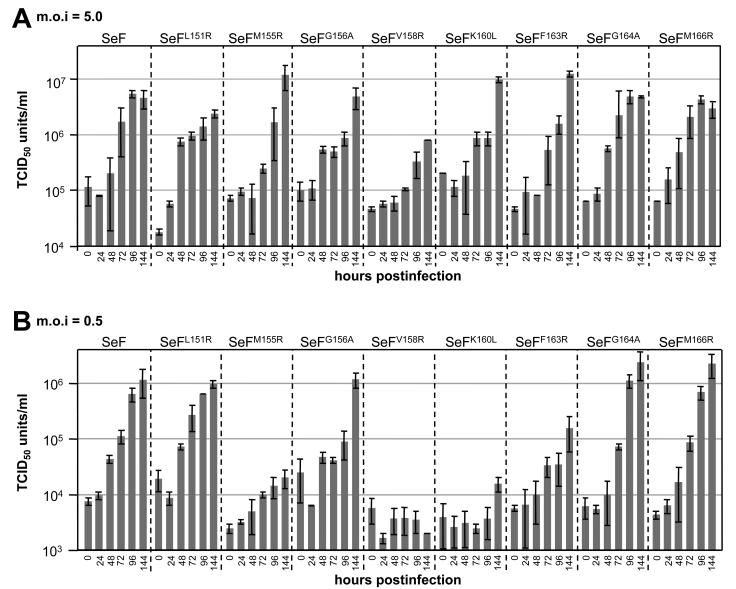

Viral infectivity of f gene-pseudotyped gp64-null AcMNPV viruses.

To characterize the effect of the mutations on viral infectivity of the mutant gp64-null viruses, one-step growth experiments were performed. Sf21 cells were infected at an MOI of 5.0 TCID50 U/cell. At different time points postinfection, the amount of infectious BVs was determined (Fig. 6A). The virus titers for the native SeF and the SeFNdeI mutant were not significantly different, indicating that the silent mutation to generate the NdeI site had no effect on BV infectivity and propagation. The one-step growth results for SeFNdeI is therefore left out of the graph (Fig. 6). Except for SeFV158R, the virus titers of the other mutants did not significantly differ from that of SeF. The virus titer of SeFV158R remained significant lower than that of the authentic SeF. This indicates that the mutations had hardly any effect on the amount of BV produced over time. A different behavior was seen when Sf21 cells were infected at an MOI of 0.5 TCID50 U/cell (Fig. 6B), so that not all cells were infected in the first round. In this experiment, the effect of the mutations on viral infectivity could be determined, since the amount of BV production over time was not altered, except for SeFV158R. Also, this time the virus titers of SeFNdeI were almost identical to that of SeF (data not shown). In the situation of 0.5 TCID50 U/cell, only the one-step growth results for SeFL151R, SeFG164A, and SeFM166R were similar to those for SeF. The titer of SeFG156A shows a drop between 48 and 72 h postinfection, but at 144 h postinfection, the titer was elevated to levels similar to that of SeF. The virus titers of SeFM155R, SeFV158R, SeFK160L, and SeFF163R showed a dramatic decrease compared to that of SeF. Thus, mutations in the fusion peptide affect viral infectivity (Fig. 6B), presumably the dynamics of viral spread, rather than viral production (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

One-step growth results are shown for gp64-null AcMNPV viruses pseudotyped with wild-type SeF and SeF mutants as described in the legend to Fig. 3. Sf21 cells were infected with an MOI of 5.0 TCID50 U/cell (A) or 0.5 TCID50 U/cell (B), and supernatants were harvested at the indicated times postinfection and titrated on Sf9Op1D cells. Each data point represents the average of the results from two or three independent infections. Error bars represent standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

Posttranslational cleavage is a general mechanism to activate the fusion proteins of enveloped viruses (21). Recently, it has been shown that this is also the case for the baculovirus F protein, where two subunits are generated, F1 and F2 (24, 43). Cleavage of envelope fusion proteins usually occurs in front of a conserved hydrophobic region, the fusion peptide. The N terminus of the SeMNPV membrane-anchored domain (F1) contains striking similarities with the fusion peptides of other viruses: (i) the domain is well conserved among its functional homologs, (ii) it is relatively hydrophobic, (iii) it can be modeled as an amphipathic helix, and (iv) it contains conserved glycines at one side of the helix (Fig. 1 and 2). The helical nature of the corresponding region of LdMNPV F has recently been determined by circular dichroism (M. Pearson and G. F. Rohrmann, Abstr. 22nd Annu. Meet. Am. Soc. Virol., abstr. W53-5, 2003).

However, there are also some striking differences with vertebrate viral fusion peptides. Fusion peptides of the latter are rich in alanines while the first alanine (residue 22) in the SeMNPV F1 N terminus is found outside the conserved region. Another difference is that N-terminal fusion peptides of most vertebrate viral fusion proteins are generally apolar, whereas the SeMNPV F1 N terminus contains six polar amino acids (N153, H157, D159, K160, D167, and S168). Other baculovirus F proteins may have up to nine polar amino acids in this region (Fig. 1). However, the fusion peptide of influenza hemagglutinin also contains two to three polar residues (26). It is very well possible that the polar amino acids force the N terminus of F1 to insert in the membrane in a more perpendicular angle, with the polar amino acids to the hydrophilic side of the phospholipids compared to other fusion peptides.

The importance of the SeMNPV F1 N terminus for virus infection and propagation was investigated by a series of amino acid substitutions. AcMNPV virions, lacking gp64, were pseudotyped with mutant f genes and assayed (results are summarized in Table 2). A similar experimental system has been used to analyze the effect of mutations in the Ebola virus glycoprotein fusion peptide through pseudotyping of the vesicular stomatitis virus lacking its own fusion protein (18). The F protein with a deletion of the N terminus (SeFΔ151-170) was not able to produce infectious virus (Fig. 3), in spite of its ability to be incorporated in BVs and the occurrence of the posttranslational cleavage (Fig. 5). This suggests that this domain is not involved in virion assembly but plays an important role in baculovirus entry into cells.

TABLE 2.

Summary of obtained resultsa

| gp64-null bacmid | Rescue | PCR | Western blot analysis with:

|

Viral propagation at an MOI of:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F incorporation | F cleavage | 5.0 | 0.5 | |||

| Controls | ||||||

| AcGP64 | +++ | √ | NA | NA | +++ | +++ |

| SeF | ++ | √ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| SeFR149K | − | √ | + | − | NA | NA |

| ΔF | − | √ | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Mutants | ||||||

| SeFNdeI | ++ | √ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| SeFL151R | ++ | √ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| SeFF152R | − | √ | + | + | NA | NA |

| SeFM155R | + | √ | + | + | ++ | + |

| SeFG156A | ++ | √ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| SeFV158R | + | √ | ++ | + | + | + |

| SeFK160L | + | √ | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| SeFF163R | + | √ | ++ | + | ++ | + |

| SeFG164A | ++ | √ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| SeFM166R | ++ | √ | ++ | + | ++ | ++ |

| SeFΔ151-170 | − | √ | ++ | + | NA | NA |

√, in agreement with the expectancy; NA, not applicable; +++, good; ++, fair; +, bad; −, none.

Glycines, as well as their conserved positions in the fusion peptides, seem to be important for the function of viral fusion proteins (7). It is supposed that glycine residues may provide the proper balance of amphipathicity necessary for merging virus and cell membranes or may be important for an oblique insertion of the fusogenic peptide into the target membrane (15). In this study, the specific role of the two conserved glycine residues in the putative fusion peptide of SeMNPV F was addressed by converting these into alanines. These substitutions might increase the stability of the possible α-helical conformation of the F1 N terminus. The G-to-A mutations in the Sendai virus fusion peptide led to increased fusion activity of the fusion protein (16) while for the Semliki Forest virus E1 protein it caused fusion at a lower pH (22). With the SeMNPV F protein, the G-to-A mutations showed no notable effect. However, these results are in line with results obtained for the Ebola virus glycoprotein fusion peptide (18), where one of the mutations of the glycines also had no effect on the virus titer and the incorporation of the fusion protein in virions.

Arginine was substituted for conserved as well as nonconserved hydrophobic residues in the fusion peptide of the SeMNPV F protein. Introduction of a polar residue in the hydrophobic face of the amphipathic helix is expected to result in either a shorter (SeFL151R or SeFM166R), narrower (SeFF152R, SeFM155R, or SeFF163R), or disrupted (SeFV158R) hydrophobic face. The alterations can possibly disturb the helical conformation or the insertion of the helix in the host membrane and, hence, may have an effect on infectivity. Leucine was substituted for the conserved polar lysine (SeFK160L), which decreases the hydrogen bonding potency of the back face of the helix. Despite all the substitutions, there was no notable effect on incorporation of F proteins in BVs and on the processing of the mutant F proteins (Fig. 5). Only SeFF152R was not able to produce infectious virus (Fig. 3), suggesting a critical role of this amino acid in fusion. Similar results with an F-to-R conversion have been obtained for the Ebola glcyoprotein (18).

The virions pseudotyped with the SeFM155R, SeFF163R, SeFV158R (hydrophilic substitutions), and SeFK160L (hydrophobic substitution) genes were all impaired in their virus propagation dynamics (Fig. 6B). For SeFM155R, this could be caused by a reduced incorporation of F protein in BVs (Fig. 5, lane 7). In contrast, when cells were infected with a higher dose, only the titer of virus pseudotyped with SeFV158R was significantly lower than that of native SeF (Fig. 6A). Such a V-to-R conversion has been shown to reduce the fusion activity of the murine leukemia virus fusion protein (19). However, Western analysis suggested that the amount of BVs produced is extremely low (Fig. 5, lane 9). It is very well possible that this is due to a defect in transport of the protein to the cell membrane, caused by incorrect folding of the protein.

The mutations L151R and M166R did not result in a significant drop in virus titers, although the incorporation of SeFM166R in BVs was somewhat affected. The L151 and M166 residues are the first and the last hydrophobic amino acids of the putative fusion peptide, and this suggests that the F protein can properly function with a smaller hydrophobic face. However, this does not imply that the borders of the putative fusion peptide of SeMNPV F are well defined, because the two conserved aspartic acid residues D167 and D170 also appeared to be important for the fusogenic activity of the LdMNPV F protein (33).

The N-terminal domain of the SeMNPV F1 subunit is most likely involved in the entry and infectivity of BVs, and further credence is given for the role of this domain as a fusion peptide. Future biochemical studies involving the three-dimensional structure of the fusion peptide should indicate how the active fusion peptide is folded and how the behavior of the site-specific mutant fusion peptides can be explained. Experiments to this end are in progress.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, J. R., and J. T. McClintock. 1991. Nuclear polyhedrosis viruses of insects, p. 87-204. In J. R. Adams and J. R. Bonami (ed.), Atlas of invertebrate viruses. CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla.

- 2.Altschul, S. F., T. L. Madden, A. A. Schaffer, J. Zhang, Z. Zhang, W. Miller, and D. J. Lipman. 1997. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:3389-3402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ausubel, F. M., R. Brent, R. E. Kingston, D. D. Moore, J. G. Seidman, J. A. Smith, and K. Struhl (ed.). 1994. Current protocols in molecular biology. Greene Publishing Associates and Wiley Interscience, New York, N.Y.

- 4.Blissard, G. W., and J. R. Wenz. 1992. Baculovirus gp64 envelope glycoprotein is sufficient to mediate pH-dependent membrane fusion. J. Virol. 66:6829-6835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford, M. M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bulach, D. M., C. A. Kumar, A. Zaia, B. Liang, and D. E. Tribe. 1999. Group II nucleopolyhedrovirus subgroups revealed by phylogenetic analysis of polyhedrin and DNA polymerase gene sequences. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 73:59-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross, K. J., S. A. Wharton, J. J. Skehel, D. C. Wiley, and D. A. Steinhauer. 2001. Studies on influenza haemagglutinin fusion peptide mutants generated by reverse genetics. EMBO J. 20:4432-4442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenberg, D. 1984. Three-dimensional structure of membrane and surface proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53:595-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnier, J., D. J. Osguthorpe, and B. Robson. 1978. Analysis of the accuracy and implications of simple methods for predicting the secondary structure of globular proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 120:97-120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayakawa, T., G. F. Rohrmann, and Y. Hashimoto. 2000. Patterns of genome organization and content in lepidopteran baculoviruses. Virology 278:1-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hefferon, K. L., A. G. Oomens, S. A. Monsma, C. M. Finnerty, and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Host cell receptor binding by baculovirus GP64 and kinetics of virion entry. Virology 258:455-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herniou, E. A., T. Luque, X. Chen, J. M. Vlak, D. Winstanley, J. S. Cory, and D. R. O'Reilly. 2001. Use of whole genome sequence data to infer baculovirus phylogeny. J. Virol. 75:8117-8126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herniou, E. A., J. A. Olszewski, J. S. Cory, and D. R. O'Reilly. 2003. The genome sequence and evolution of baculoviruses. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 48:211-234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hohmann, A. W., and P. Faulkner. 1983. Monoclonal antibodies to baculovirus structural proteins: determination of specificities by Western blot analysis. Virology 125:432-444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horth, M., B. Lambrecht, M. C. Khim, F. Bex, C. Thiriart, J. M. Ruysschaert, A. Burny, and R. Brasseur. 1991. Theoretical and functional analysis of the SIV fusion peptide. EMBO J. 10:2747-2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Horvath, C. M., and R. A. Lamb. 1992. Studies on the fusion peptide of a paramyxovirus fusion glycoprotein: roles of conserved residues in cell fusion. J. Virol. 66:2443-2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IJkel, W. F. J., M. Westenberg, R. W. Goldbach, G. W. Blissard, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2000. A novel baculovirus envelope fusion protein with a proprotein convertase cleavage site. Virology 275:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito, H., S. Watanabe, A. Sanchez, M. A. Whitt, and Y. Kawaoka. 1999. Mutational analysis of the putative fusion domain of Ebola virus glycoprotein. J. Virol. 73:8907-8912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones, J. S., and R. Risser. 1993. Cell fusion induced by the murine leukemia virus envelope glycoprotein. J. Virol. 67:67-74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kingsley, D. H., A. Behbahani, A. Rashtian, G. W. Blissard, and J. Zimmerberg. 1999. A discrete stage of baculovirus GP64-mediated membrane fusion. Mol. Biol. Cell 10:4191-4200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klenk, H. D., and W. Garten. 1994. Activation of viral spike proteins by host proteases, p. 241-280. In E. Wimmer (ed.), Cellular receptors for animal viruses. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Levy-Mintz, P., and M. Kielian. 1991. Mutagenesis of the putative fusion domain of the Semliki Forest virus spike protein. J. Virol. 65:4292-4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luckow, V. A., S. C. Lee, G. F. Barry, and P. O. Olins. 1993. Efficient generation of infectious recombinant baculoviruses by site-specific transposon-mediated insertion of foreign genes into a baculovirus genome propagated in Escherichia coli. J. Virol. 67:4566-4579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lung, O., M. Westenberg, J. M. Vlak, D. Zuidema, and G. W. Blissard. 2002. Pseudotyping Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus (AcMNPV): F proteins from group II NPVs are functionally analogous to AcMNPV GP64. J. Virol. 76:5729-5736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik, H. S., S. Henikoff, and T. H. Eickbush. 2000. Poised for contagion: evolutionary origins of the infectious abilities of invertebrate retroviruses. Genome Res. 10:1307-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin, I., J. M. Ruysschaert, and R. M. Epand. 1999. Role of the N-terminal peptides of viral envelope proteins in membrane fusion. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 38:233-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monsma, S. A., A. G. Oomens, and G. W. Blissard. 1996. The GP64 envelope fusion protein is an essential baculovirus protein required for cell-to-cell transmission of infection. J. Virol. 70:4607-4616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholas, K. B., H. B. Nicholas, Jr., and D. W. Deerfield. 14 October 2002. Genedoc: analysis and visualization of genetic variation. EMBnet News 4:14. [Online.] http://www.hgmp.mrc.ac.uk/embnet.news/vol4_2/genedoc.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oomens, A. G., and G. W. Blissard. 1999. Requirement for GP64 to drive efficient budding of Autographa californica multicapsid nucleopolyhedrovirus. Virology 254:297-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Reilly, D. R., L. K. Miller, and V. A. Luckow. 1992. Baculovirus expression vectors: a laboratory manual. W. H. Freeman and Co., New York, N.Y.

- 31.Ozers, M. S., and P. D. Friesen. 1996. The Env-like open reading frame of the baculovirus-integrated retrotransposon TED encodes a retrovirus-like envelope protein. Virology 226:252-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pearson, M. N., C. Groten, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2000. Identification of the Lymantria dispar nucleopolyhedrovirus envelope fusion protein provides evidence for a phylogenetic division of the Baculoviridae. J. Virol. 74:6126-6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson, M. N., R. L. Russell, and G. F. Rohrmann. 2002. Functional analysis of a conserved region of the baculovirus envelope fusion protein, LD130. Virology 304:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pearson, W. R. 1990. Rapid and sensitive sequence comparison with FASTP and FASTA. Methods Enzymol. 183:63-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plonsky, I., M. S. Cho, A. G. Oomens, G. Blissard, and J. Zimmerberg. 1999. An analysis of the role of the target membrane on the Gp64-induced fusion pore. Virology 253:65-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rohrmann, G. F., and P. A. Karplus. 19 February 2001, posting date. Relatedness of baculovirus and gypsy retrotransposon envelope proteins. BMC Evol. Biol. 1:1. [Online.] http://www.biomedcentral.com. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharrocks, A. D., and P. E. Shaw. 1992. Improved primer design for PCR-based, site-directed mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Song, S. U., T. Gerasimova, M. Kurkulos, J. D. Boeke, and V. G. Corces. 1994. An env-like protein encoded by a Drosophila retroelement: evidence that gypsy is an infectious retrovirus. Genes Dev. 8:2046-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tanda, S., J. L. Mullor, and V. G. Corces. 1994. The Drosophila tom retrotransposon encodes an envelope protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:5392-5401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thiem, S. M., and L. K. Miller. 1990. Differential gene expression mediated by late, very late and hybrid baculovirus promoters. Gene 91:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vaughn, J. L., R. H. Goodwin, G. J. Tompkins, and P. McCawley. 1977. The establishment of two cell lines from the insect Spodoptera frugiperda (Lepidoptera; Noctuidae). In Vitro 13:213-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volkman, L. E., and P. A. Goldsmith. 1985. Mechanism of neutralization of budded Autographa californica nuclear polyhedrosis virus by a monoclonal antibody: inhibition of entry by adsorptive endocytosis. Virology 143:185-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Westenberg, M., H. Wang, W. F. IJkel, R. W. Goldbach, J. M. Vlak, and D. Zuidema. 2002. Furin is involved in baculovirus envelope fusion protein activation. J. Virol. 76:178-184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.White, J. M. 1990. Viral and cellular membrane fusion proteins. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 52:675-697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White, J. M. 1992. Membrane fusion. Science 258:917-924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]