Abstract

Objective

Thresholds of minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) are needed to plan and interpret clinical trials. We estimated MCIIs for the rheumatoid arthritis (RA) activity measures of patient global assessment, pain score, Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index (HAQ), Disease Activity Score-28 (DAS28), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), and Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI).

Methods

In this prospective longitudinal study, we studied 250 patients who had active RA. Disease activity measures were collected before and either 1 month (for patients treated with prednisone) or 4 months (for patients treated with disease modifying medications or biologics) after treatment escalation. Patient judgments of improvement in arthritis status were related to prospectively assessed changes in the measures. MCIIs were changes that had a specificity of 0.80 for improvement based on receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. We used bootstrapping to provide estimates with predictive validity.

Results

At baseline, the mean (± standard deviation) DAS28-ESR was 6.16 ± 1.2 and mean SDAI was 38.6 ± 14.8. Improvement in overall arthritis status was reported by 167 patients (66.8%). Patients were consistent in their ratings of improvement versus no change or worsening, with receiver operating characteristic curve areas ≥ 0.74. MCIIs with a specificity for improvement of 0.80 were: patient global assessment −18, pain score −20, HAQ −0.375, DAS28-ESR −1.2, DAS28-CRP −1.0, SDAI −13, and CDAI −12.

Conclusions

MCIIs for individual core set measures were larger than previous estimates. Reporting the proportion of patients who meet these MCII thresholds can improve the interpretation of clinical trials in RA.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, clinically important improvement, disease activity, response measures

Interpretation of the results of clinical trials requires an assessment of not only the statistical significance of treatment differences but also of their clinical importance. Clinically important changes are those recognized as meaningful improvements (or deteriorations), most often judged by patients experiencing the change (1). To aid the interpretation of clinical trials, these judgments must be related to corresponding changes in measures of disease activity used as endpoints in trials (2). This translation is critical, because underestimation or overestimation of the thresholds for clinically important changes can have major consequences. If thresholds are set too high, meaningful improvements may be overlooked. If thresholds are too low, treatments that result in trivial improvements may be mistakenly considered beneficial. Clinically important changes are also important components in sample size calculations for clinical trials.

Few studies have attempted to define clinically important changes in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) activity measures, with little consensus. Early studies suggested that a difference of 10 points on a 100-point patient global assessment scale, 6 points on a 100-point pain scale, and 0.20–0.22 units on the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) Disability Index could be considered clinically important (3,4). These data were based on studies of 40 to 57 patients who rated their status relative to each other after brief conversations. These group-level between-patient contrasts differ importantly from the within-patient longitudinal contrasts that are most directly applicable to clinical trials (2,3). In two short-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug trials, changes in the patient global assessment of 14 points, pain score of 15 points, and modified HAQ of 0.24 units were judged as important, while slightly larger changes were identified in a registry study (5–7). However, an observational study of patients in routine care reported thresholds of 11.9 points for the pain score and 0.09 units for the HAQ (8). Despite the growing use of composite RA activity measures, only one study has examined clinically important changes in the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28), Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), or Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) from the patient’s perspective (9). Testing of clinically important improvements was highlighted as an important next step in the development of RA clinical trials (10).

Our aim was to identify thresholds for minimal clinically important improvement (MCII) in the RA core set measures of patient global assessment, pain score, and HAQ, and for the DAS28, SDAI, and CDAI. We examined longitudinal within-patient changes from the patient’s perspective, analyzed at the individual level (2). We studied patients with active RA who were having treatment escalation to provide results applicable to clinical trials.

METHODS

Participants

We enrolled patients who were receiving ongoing care in our clinics. Participants were required to be age 18 or older, have a clinical diagnosis of RA and fulfill the 1987 American College of Rheumatology classification criteria (11), and have active RA based on physician judgment and at least six tender joints. Patients were enrolled only if they had an escalation of anti-rheumatic treatment for active RA at the baseline visit. This escalation could be an increased dose of their current DMARD, initiation of prednisone, or initiation of a new disease modifying medication (DMARD) or biologic (henceforth, dose-escalation, prednisone, and DMARD groups, respectively). Decisions regarding the specific medication changes were left to the treating rheumatologist and not determined by this study. The study was approved by the institutional review board, and all patients provided written informed consent.

Study procedures

Patients completed two study visits. Because responses to prednisone were anticipated to occur sooner than responses to the other treatments, the follow-up visit for patients in the prednisone group was at 1 month, while for all others the follow-up visit was at 4 months. Interim visits were not performed. We chose 4 months to allow time for clinical responses while limiting the potential for poorer recall with a longer interval.

At both visits, patients had complete joint counts (66 swollen, 68 tender) by same rheumatologist, and testing of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) level. The examining rheumatologist provided a global assessment of arthritis activity. Patients completed questionnaires including a global assessment by visual analog scale (possible range 0 – 100 with anchors of very well and very poor), pain score by visual analog scale (possible range 0 – 100 with anchors of no pain and severe pain), and HAQ (possible range 0 – 3, with higher scores indicating more difficulty) (12). We used the relevant measures to compute the DAS28-ESR, DAS28-CRP, SDAI, and CDAI (13–15).

At the follow-up visit, patients completed a transition question on whether they judged their arthritis overall to be improved, unchanged, or worsened since the baseline visit, and to rate the importance of any change on a 7-point scale (from “hardly important at all” to “extremely important”) (16). Identical questions were asked about changes in pain and ability to do things.

Statistical analysis

We first examined changes in RA activity measures to establish their sensitivity to change and the validity of the judgment process. To provide valid MCIIs, measures must be sensitive to change. If a measure is not sensitive to change, patients may experience important improvements in disease activity, yet these improvements would correspond to only small changes in the measure, resulting in small changes being mistakenly labeled as important. RA activity measures have been reported to be sensitive to change (17–23), but because this can vary with the intervention (24), degree of RA activity (25), or duration of RA (26,27), it is important to verify it in each sample. We measured sensitivity to change using standardized response means (SRM), with SRMs ≤ −0.50 considered acceptable (28–30). We computed confidence intervals for SRMs using 2000 bootstrapped samples. To assess the validity of the judgment process, we tested if changes in RA measures differed among patients who reported improvement, no change, or worsening, using one-way analysis of variance.

Next, we determined if patients were similar in their judgments of what degree of improvement constituted an important change. If patients were not similar, criteria for groups of patients could not be established. We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, with responses to the transition question (improved or not) as the outcome and change in the RA activity measure as the independent variable, and computed 95% confidence intervals for the area under the ROC curve (31,32). Values of 1.0 for the area under the ROC curve indicate perfect separation between those reporting improvement and those not reporting improvement, while values of 0.5 indicate no discrimination. We considered judgments among patients to be similar if the 95% lower bound of the ROC area excluded 0.5. To provide results with predictive validity, we computed ROC curves on 2000 bootstrapped samples, using non-parametric resampling and the bias-corrected and accelerated method to compute confidence intervals [33]

We also used the ROC curves to determine MCIIs. We used the change score at a specificity for improvement of 0.80, following previous studies (7,34). This measure indicates the degree of change that 80% or more of patients would indicate as being important. We computed two alternative criteria for the MCII, based on either the Youden index or the minimal distance to the upper left corner [0, 1] of the ROC curve plot (35). These latter methods do not ensure minimum thresholds for specificity, and may identify thresholds with varying sensitivities and specificity among measures, and therefore are less appealing for determining MCIIs.

For all measures except the HAQ, we computed the mean change as the MCII. Because the HAQ is an ordinal measure with increments of 0.125, we computed median changes for its MCII.

A sample of 250 patients with 225 patients who reported improvement and 25 who did not report improvement was estimated to have an ROC curve area that was significantly greater than 0.5 (i.e 0.53, 0.67 with type 1 error (two-tailed) of 0.05)(36). Samples more balanced with respect to the proportions reporting improvement would have even more statistical power. In exploratory analyses, we examined patient subgroups.

We used SAS programs version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) for analysis.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

We enrolled 262 patients, of whom 250 completed the study. Eight patients were lost to follow-up, two withdrew, one died of a stroke before the second visit, and one did not complete questionnaires at the second visit. Most patients were middle-aged women (Table 1). The median duration of RA was 6.4 years; 60 patients (24%) had RA for less than 2 years. At enrollment, 87 patients (35%) were being treated with methotrexate (median dose 15 milligrams per week), and 88 patients (35%) were being treated with prednisone (median dose 5 milligrams per day). Seventy-one patients (28%) were DMARD-naïve.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics at study entry (N = 250).*

| Age, years | 51.0 ± 13.7 |

| Women | 195 (78%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 102 (40.8%) |

| Hispanic | 73 (29.2%) |

| Black | 56 (22.4%) |

| Asian | 17 (6.8%) |

| Multi-ethnic | 2 (0.8%) |

| Formal education, years | 13 (12, 16) |

| Duration of RA, years | 6.4 (2.2, 14.5) |

| Seropositive | 188 (75.2%) |

| Erosive | 141 (63.8%)† |

| Swollen joint count (0 – 66) | 15 (9, 22) |

| Swollen joint count (0 – 28) | 11 (7, 16) |

| Tender joint count (0 – 68) | 22 (13, 35) |

| Tender joint count (0 – 28) | 14 (8, 21) |

| Physician global assessment (0 – 100) | 48.2 ± 17.5 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/hr) | 40 ± 27 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 7.4 (4.0, 19.5) |

| Medications at entry | |

| Methotrexate | 87 (35%) |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 64 (25.7%) |

| Sulfasalazine | 24 (9.6%) |

| Leflunomide | 16 (6.4%) |

| Prednisone | 88 (35%) |

| Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors | 28 (11.2%) |

| Other biologics | 2 (0.8%) |

| Study treatment group | |

| Dose escalation | 104 (41.6%) |

| Prednisone initiation | 56 (22.4%) |

| DMARD initiation | 90 (36%) |

Plus-minus values are mean ± standard deviation. N (N, N) values are median (25th, 75th percentile). All other values are number (percentage).

Of 221 patients with radiographs.

Patients had active RA, with mean DAS28-ESR of 6.16 (Table 2). All but three patients had a DAS28-ESR > 3.2, and 203 patients (81%) had a DAS28-ESR > 5.1. All but 1 patient had a SDAI > 11 and CDAI > 10; 197 patients (79%) had an SDAI > 26 and 214 patients (85%) had a CDAI > 22. One hundred four patients (41.6%) were in the dose-escalation group, 56 patients (22.4%) were in the prednisone initiation group, and 90 patients (36%) were in the DMARD initiation group. In the latter group, 60 patients started methotrexate, 3 started leflunomide, 20 started tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors, and 7 started other biologics.

Table 2.

Changes in rheumatoid arthritis activity measures during the study.*

| Measure (possible range) |

Baseline | Follow-up | Mean change |

SRM (95% CI) | Mean change by Improvement category |

P (ANOVA) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improved | Stayed the same |

Worsened | ||||||

| Patient global assessment (0 – 100) |

55.6 ± 25.2 | 37.6 ± 24.0 | −18.0 ± 26.4 | −0.68 (−0.60, −0.77) | −24.7 | −7.2 | 3.1 | <.0001 |

| Pain (0 – 100) | 60.5 ± 25.3 | 39.7 ± 27.0 | −21.0 ± 30.3 | −0.69 (−0.61, −0.78) | −29.7 | −8.2 | 2.2 | <.0001 |

| HAQ (0 – 3) | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.0 ± 0.7 | −0.4 ± 0.6 | −0.65 (−0.58, −0.72) | −0.63 | −0.08 | 0.06 | <.0001 |

| DAS28-ESR (0 – 9.4) | 6.16 ± 1.2 | 4.84 ± 1.38 | −1.31 ± 1.34 | −0.98 (−0.90, −1.07) | −1.67 | −0.62 | −0.2 | <.0001 |

| DAS28-CRP (1 – 9.4) | 5.55 ± 1.09 | 4.34 ± 1.26 | −1.23 ± 1.30 | −0.95 (−0.87, −1.04) | −1.60 | −0.59 | −0.06 | <.0001 |

| SDAI (0 – 86) | 38.6 ± 14.8 | 24.0 ± 13.9 | −14.9 ± 15.3 | −0.97 (−0.90, −1.07) | −19.3 | −7.4 | −1.28 | <.0001 |

| CDAI ( 0 – 76) | 36.8 ± 13.5 | 23.0 ± 13.6 | −13.7 ± 14.1 | −0.98 (−0.90, −1.08) | −18.0 | −6.7 | −1.2 | <.0001 |

SRM = standardized response mean; CI = confidence interval; ANOVA = analysis of variance; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; DAS28-ESR = Disease Activity Score 28 Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; DAS28-CRP = Disease Activity Score 28 C-reactive Protein; SDAI = Simplified Disease Activity Index; CDAI = Clinical Disease Activity Index.

Plus-minus values are mean ± standard deviation.

Changes in RA activity

Mean RA activity improved substantially during the study (Table 2). Each measure was sensitive to change, with SRMs for the patient-reported measures of −0.65 to −0.69, and for the composite measures of −0.95 to −0.98. Overall, 167 patients (66.8%) reported that their global arthritis status had improved, 59 (23.6%) reported no change, and 24 (9.6%) reported worsening. Frequencies of subjective changes in pain (65.2% improved; 23.2% no change; 11.6% worsened) and functional ability (60.4% improved; 30.8% no change; 8.8% worsened) were similar. Ninety-two percent of patients who reported improvement in their global arthritis status rated the improvement as at least moderately important, and 68% rated it as either very important or extremely important. Those who reported improvement had significantly larger changes in each measure than those who reported no change or worsening (Table 2).

Similarity of Judgments among Patients

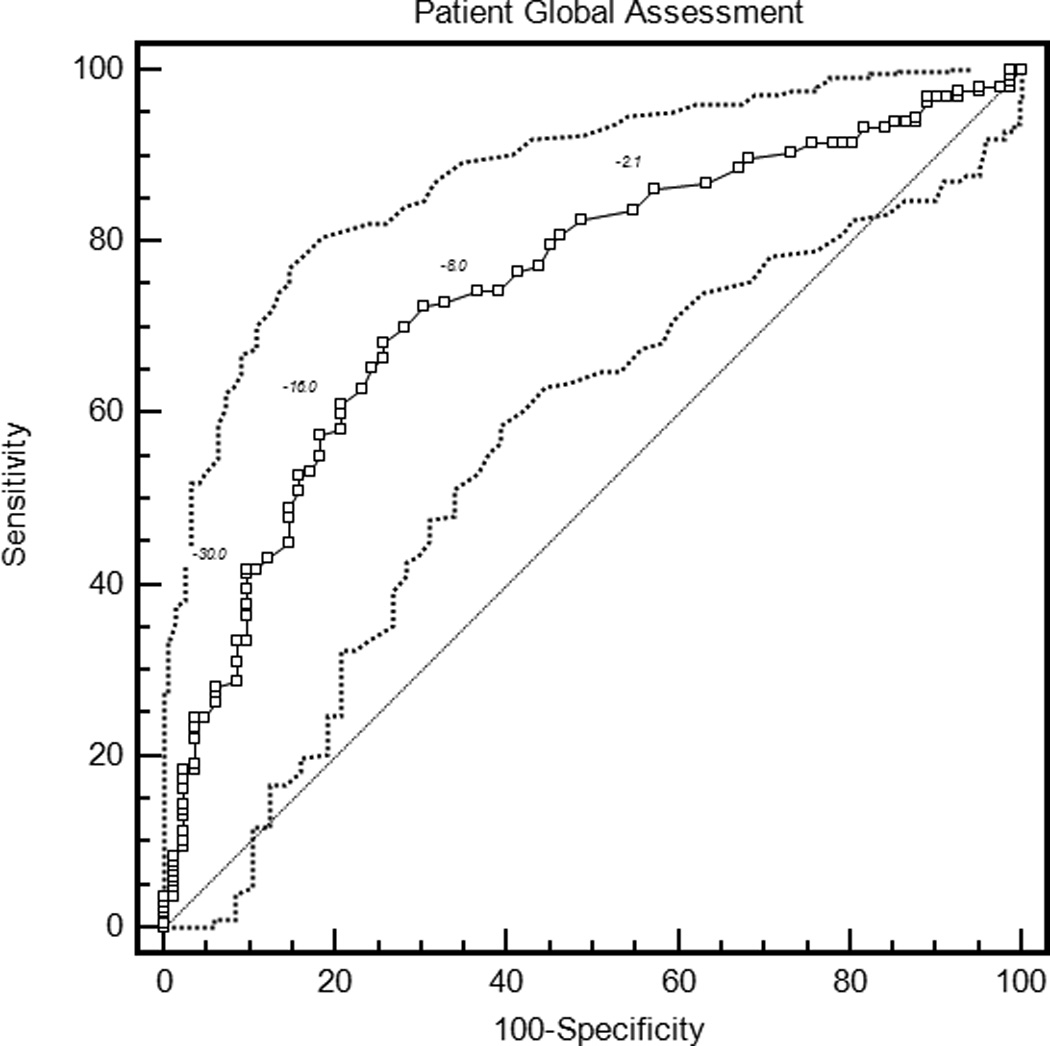

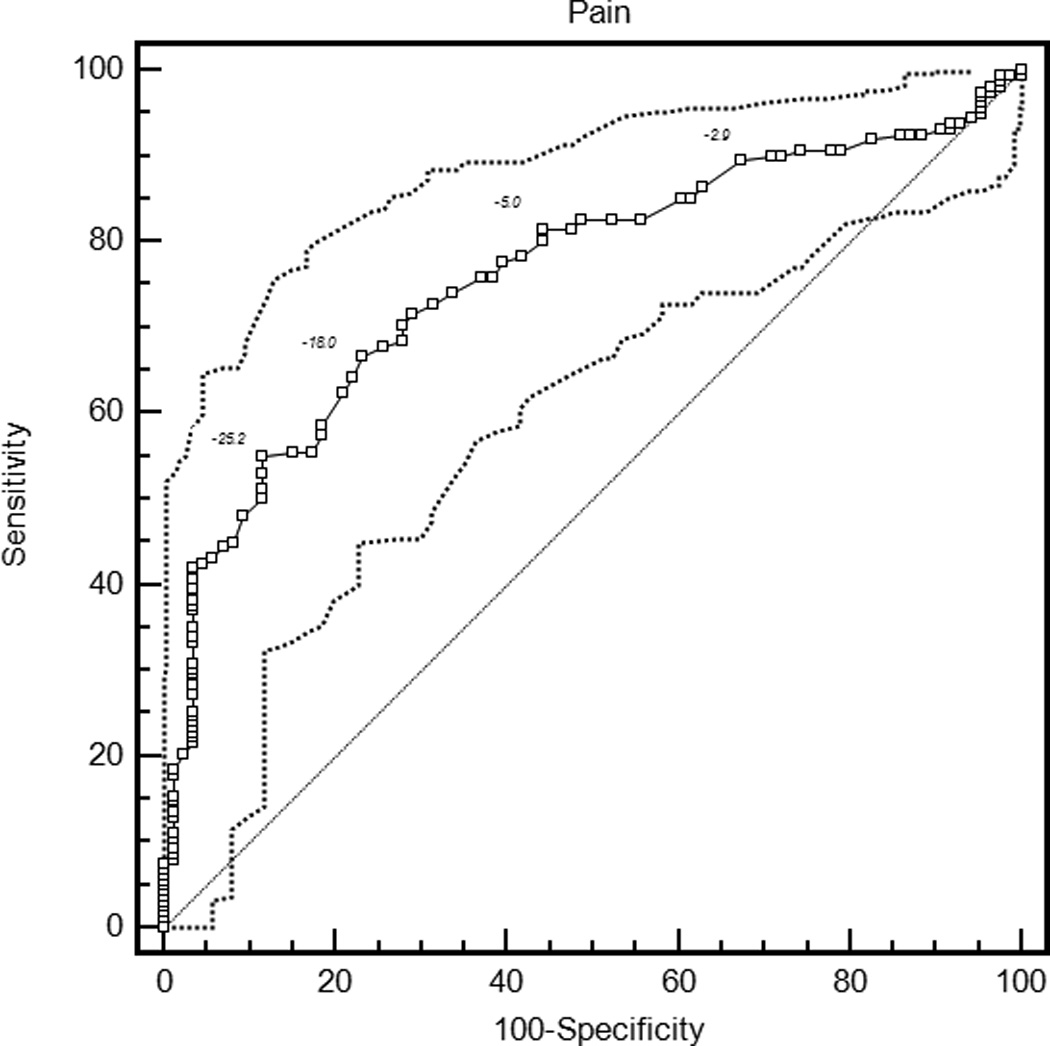

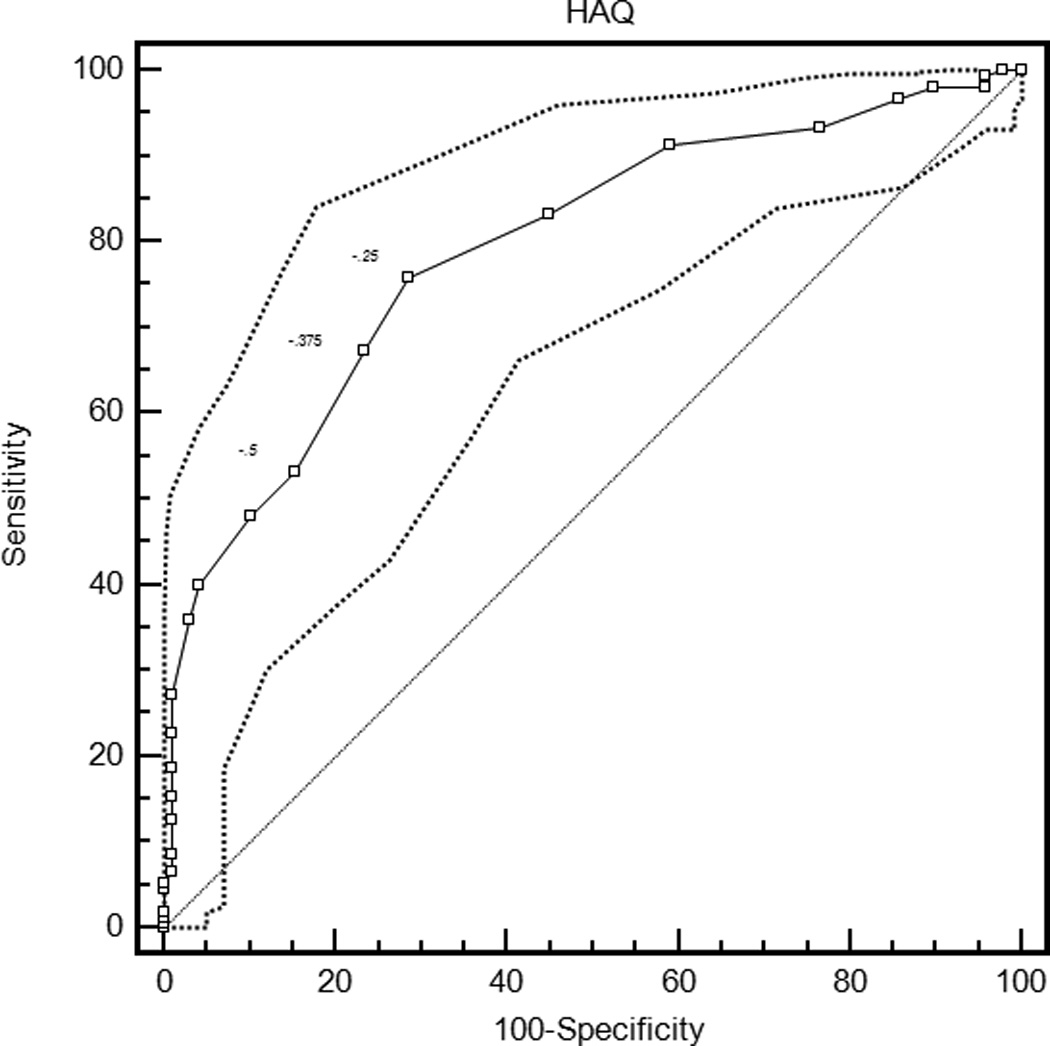

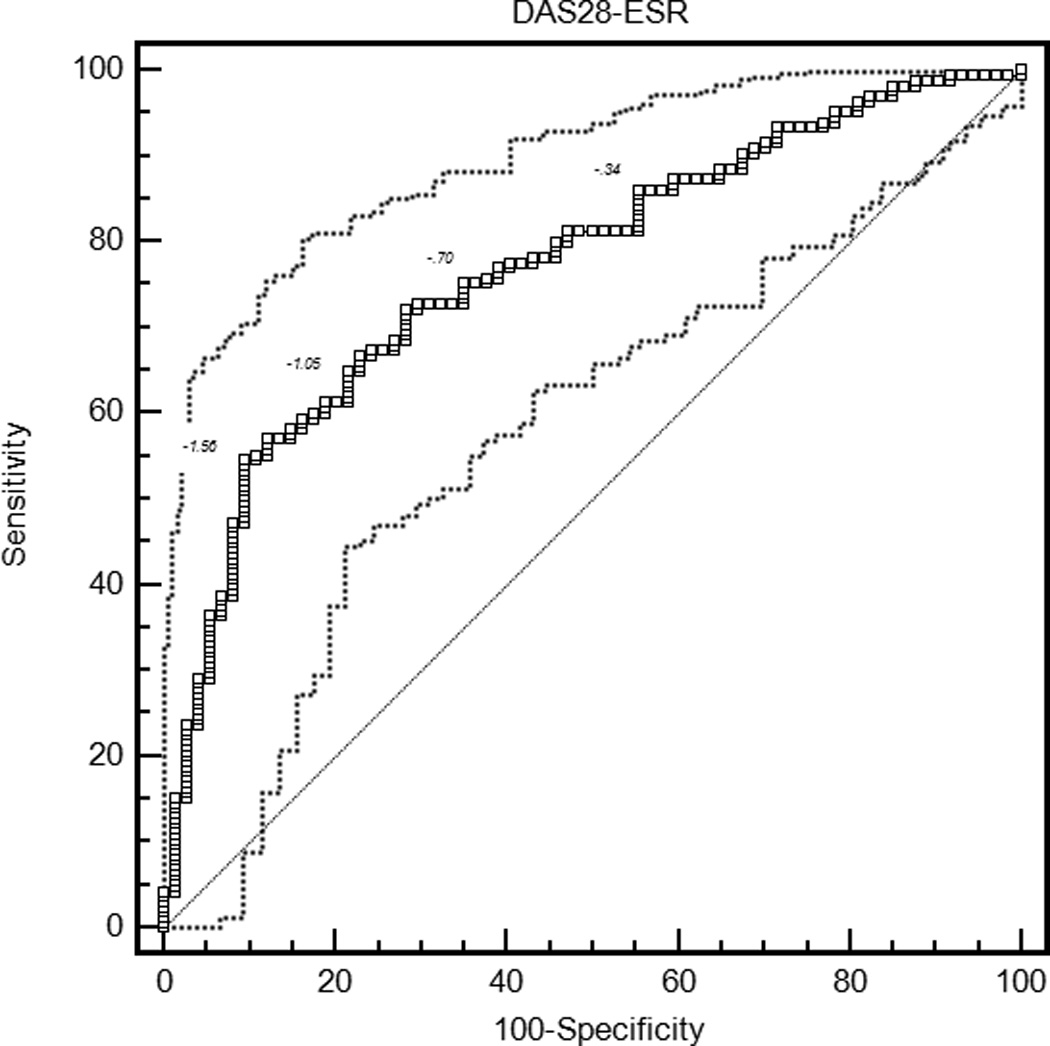

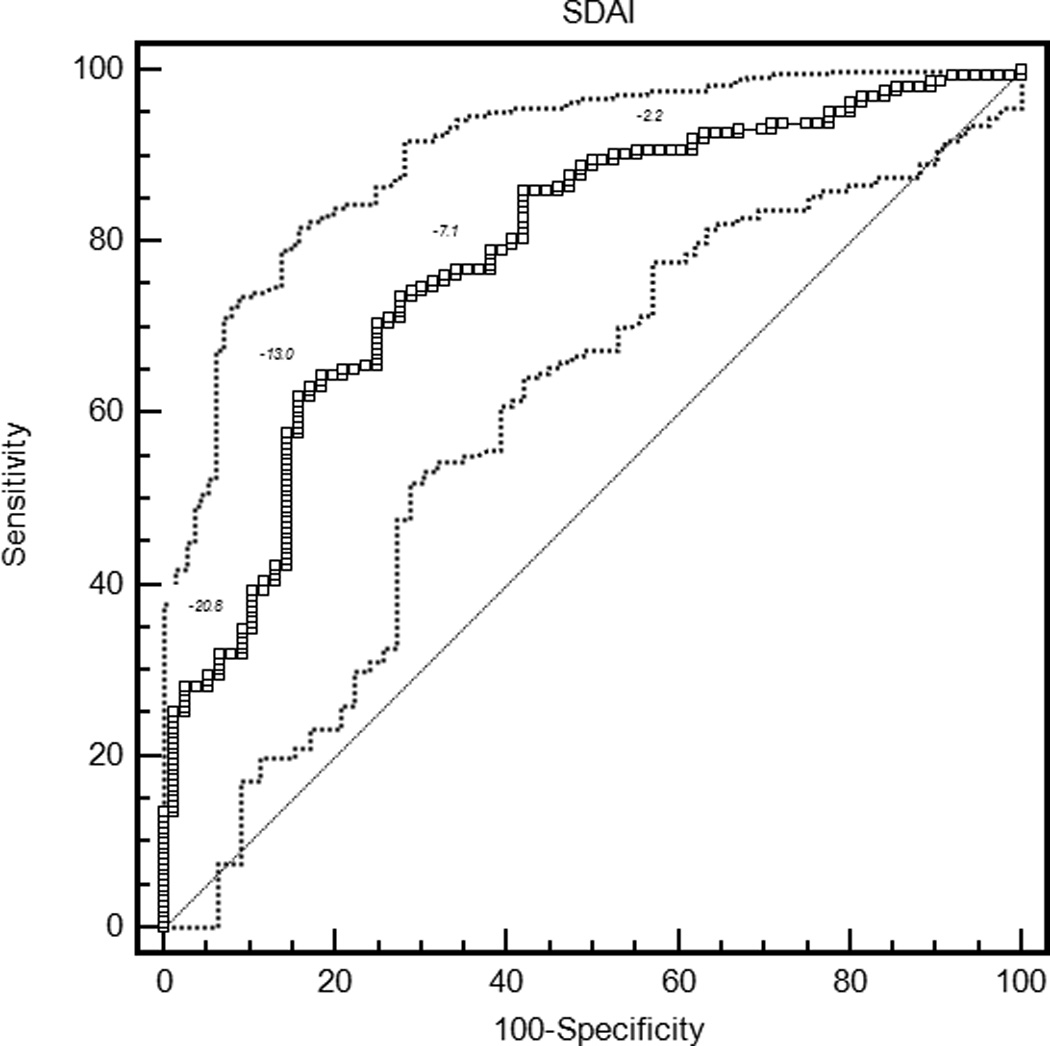

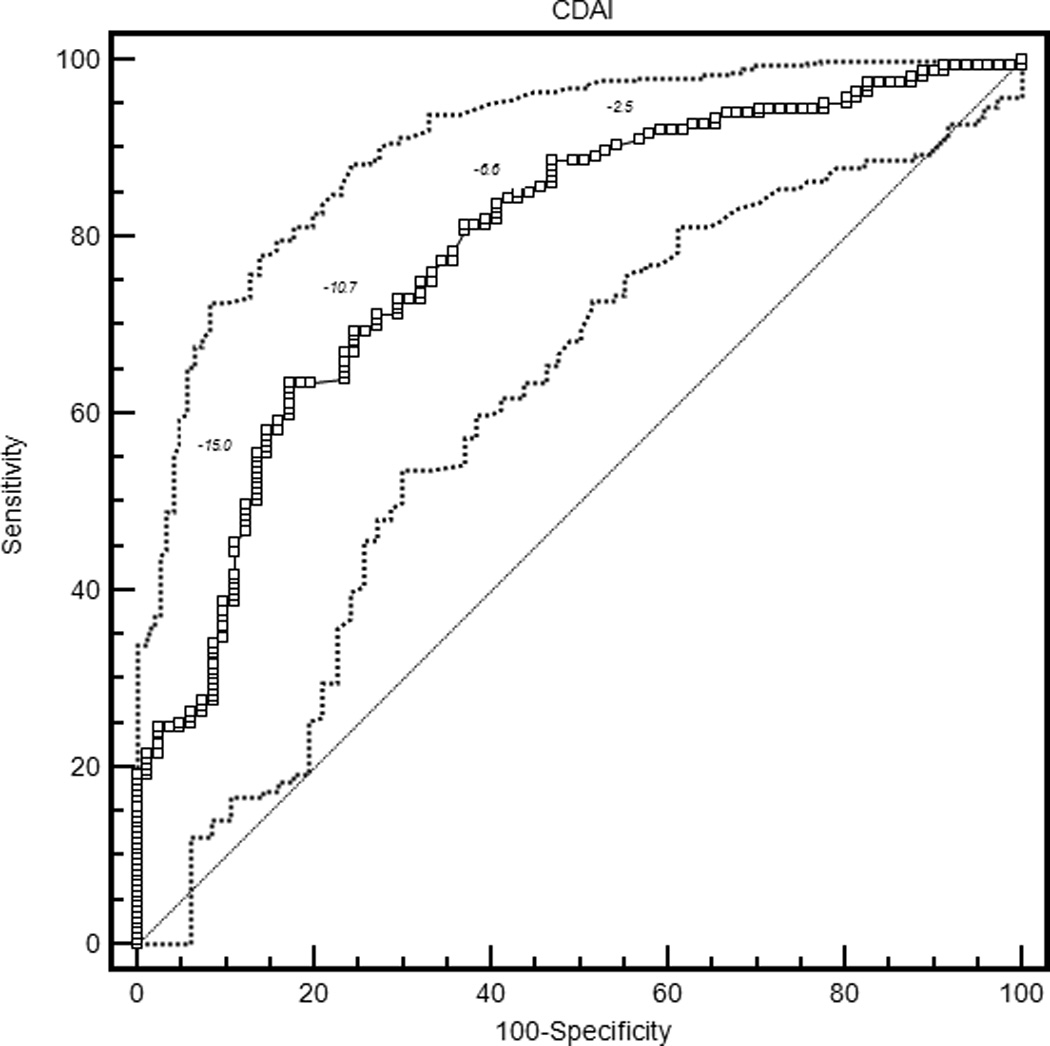

The mean ROC curve area ranged from 0.74 for the patient global assessment to 0.79 for the HAQ and DAS28-CRP (Table 3). The lower confidence limit was greater than 0.5 for each measure, indicating that patients were sufficiently similar in their judgments of improvement that MCIIs for the group could be estimated. ROC curves are presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Minimal clinically important improvement estimates for individual and composite rheumatoid arthritis activity measures, using a specificity of 0.80 as the criterion.

| Measure | ROC Curve Area (95% CI) | MCII (95% CI) | Sensitivity (95% CI) | % Misclassified (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient global assessment | 0.74 (0.68, 0.80) | −18.4 (−26.0, −12.0) | 0.58 (0.39, 0.72) | 34.6 (30.0, 39.1) |

| Pain | 0.76 (0.69, 0.82) | −20.4 (−24.0, −17.1) | 0.61 (0.50, 0.74) | 33.3 (30.3, 39.4) |

| HAQ | 0.79 (0.73, 0.85) | −0.375 (−0.5, −0.25)† | 0.62 (0.55, 0.74) | 28.8 (23.4, 34.8) |

| DAS28-ESR | 0.77 (0.71, 0.82) | −1.17 (−1.36, −0.87) | 0.62 (0.48, 0.72) | 34.9 (30.4, 39.3) |

| DAS28-CRP | 0.79 (0.73, 0.84) | −1.02 (−1.44, −0.83) | 0.64 (0.43, 0.76) | 32.4 (27.0, 36.3) |

| SDAI | 0.78 (0.73, 0.84) | −13.1 (−17.5, −10.7) | 0.63 (0.37, 0.76) | 32.1 (27.5, 36.7) |

| CDAI | 0.78 (0.73, 0.84) | −12.5 (−14.7, −10.5) | 0.63 (0.47, 0.75) | 30.9 (27.2, 36.3) |

Values are means of 2000 bootstrapped samples.

ROC = receiver operating characteristic; CI = confidence interval; MCII = minimal clinically important improvement; HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; DAS28-ESR = Disease Activity Score 28 Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; DAS28-CRP = Disease Activity Score 28 C-reactive Protein; SDAI = Simplified Disease Activity Index; CDAI = Clinical Disease Activity Index.

Median (5th, 95th percentile)

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic curves for rheumatoid arthritis activity measures. HAQ = Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index; DAS28-ESR = Disease Activity Score 28 Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate; DAS28-CRP = Disease Activity Score 28 C-reactive Protein; SDAI = Simplified Disease Activity Index; CDAI = Clinical Disease Activity Index.

MCII estimates

With the criterion of a specificity of 0.80, an improvement of 18 points on the patient global assessment (rounded estimates are conventionally used in clinical applications) and 20 points on the pain score were the thresholds for MCII (Table 3). Similarly, an improvement in the HAQ by 0.375 was the MCII estimate. The MCII for the DAS28-ESR was 1.2 and for the DAS28-CRP was 1.0, while estimates for the SDAI and CDAI were 13 and 12 points, respectively. The confidence intervals show the range of variability in estimates of MCII among the 2000 bootstrapped samples. Sensitivities ranged from 0.58 to 0.64, indicating that by requiring high specificity, a sizable proportion of patients with subjective improvement did not meet the MCII thresholds. The proportion of patients misclassified (that is, either reported subjective improvement and did not meet the MCII, or met the MCII and did not report subjective improvement) ranged from 28.8% for the HAQ to 34.9% for the DAS28-ESR.

MCII estimates based on the Youden index and the shortest distance were generally smaller than those based on the 0.80 specificity criterion, with lower specificities but higher sensitivities (see Supplemental data). Results for patient subgroups are presented in the supplemental file.

DISCUSSION

Assessing whether a patient has had a meaningful response to treatment is an activity that occurs in almost all clinical encounters. However, these judgments by patients are implicit and personal. To be applied in clinical trials, these judgments must be made explicit and mapped to corresponding changes in disease activity measures. They must also be aggregated among many patients so that estimates are generalizable. This translation requires attention to several issues: assessment of a study cohort that mirrors the patients to whom the MCIIs would be applied; confirmation of sensitivity to change; testing validity and establishing consistency of patients’ judgments; and ensuring predictive validity using resampling methods. We used this approach to derive MCIIs for RA activity measures.

The cohort was comprised predominantly of middle-aged women with seropositive erosive RA, and therefore matched the target population in many clinical studies. Patients had active RA, comparable to patients in recent trials (37,38). Most patients had substantial responses to treatment escalation, and the sensitivity to change of clinical measures equaled previous reports (18–23). Importantly, 33%-39% patients did not judge themselves as improved. This variation was needed to identify MCIIs. Most patients rated their improvement as very important or extremely important, which may reflect the types of interventions we studied, but may also indicate that patients were unlikely to endorse improvement unless it was substantial.

MCII estimates for patient global assessment, pain, and HAQ (−18, −20, and −0.375, respectively) were larger than those of several previous studies. Wells, et al, and Redelmeier and Lorig used between-patient comparisons to derive MCII estimates of −10, −6, and −0.22 for these three measures (3,4). These MCIIs relied on patients judging themselves against other patients, rather than judging their current status relative to their previous status. Between-patient comparisons may be affected by misinterpretation, nondisclosure, and optimistic bias. Given the differences in the judgment process, it is not surprising that these MCIIs differ. Because clinical assessment is concerned with whether individual patients have improved, MCIIs based on within-patient changes are likely more relevant. Even within their study, group mean differences poorly separated improved from unimproved patients, suggesting that generalizing these MCIIs may not be valid (3). Tubach et al reported MCIIs for patient global assessment and pain of −14 and −15, respectively, based on changes after 4 weeks of treatment with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (6). The specificity of these MCIIs was not reported. Pope et al studied a stable cohort in which measures changed little (8). The low MCII estimates of 11.9 for pain score and 0.09 for HAQ likely reflect misapplication in a setting with low sensitivity to change.

Our MCII estimates were similar to those of Kvamme et al, who reported MCII of −20, −19, and −0.25 for the patient global assessment, pain, and HAQ, respectively, in a RA registry (7). These investigators also used the 0.80 specificity criterion, which may have contributed similarity with our results. This approach to defining MCIIs is appealing because it establishes criteria that are highly specific and consistent across measures. Confidence that important changes have been identified favors setting the specificity high. MCIIs based on the Youden index and the shortest distance to perfect discrimination were smaller than those based on the 0.80 specificity definition, although with lower specificity and higher sensitivity. The proportions misclassified by each approach were similar, indicating that one approach did not have major net advantages in accuracy. In a recent survey, a majority of rheumatology researchers endorsed a 20-point improvement in patient global assessment (60%) and pain (53%) as the optimal MCII, consistent with our results, while 20%-27% favored a 15-point improvement (39). Similarly, a panel of pain researchers suggested that a 10-point improvement in pain represented little change, while a 20-point improvement represented meaningful improvement, associated for example with reduced analgesic use (40). Analysis of a recent etanercept trial in psoriatic arthritis suggested an MCII for the HAQ of 0.35 (41).

Although composite RA activity measures have become established outcome measures, few studies have examined their MCIIs. In a registry study of patients starting a new DMARD, MCII for the DAS28, SDAI, and CDAI were estimated as 1.20, 10.95, and 10.76 (9). These estimates were similar to our MCIIs of 1.1, 13, and 12, respectively. The MCII for the DAS28 based our patients’ judgments was very similar to the estimate of 1.2 proposed on purely statistical considerations (i.e. twice the measurement error) (42). Other studies attempted to estimate MCIIs for the DAS28, SDAI, and CDAI indirectly through comparison with American College of Rheumatology response criteria, but response criteria have a different derivation and the MCIIs were not based on patients’ perspectives (15,21,43).

Our study has several limitations. We could not examine differences between the prednisone and DMARD initiation groups, because these contrasts would be driven by differences in sensitivity to change (9). We could not examine if the timing of the second assessment influenced the results because this was collinear with the treatment group. We assessed responses over one to four months, but previous studies suggested that MCII estimates are unrelated to the assessment interval (44,45). Also, we did not study worsening. Thresholds for important improvement and worsening often differ, and these MCII estimates should not be considered thresholds for important worsening (45–48). We did not examine associations of the MCII with baseline RA activity, because these are affected by ceiling and floor effects (49). Because MCIIs reflect the composition of the sample, estimates are most representative of groups with similar disease characteristics and range of RA activity, and should not be generalized to groups with low disease activity.

Along with knowing the proportion of patients in remission or low disease activity at the end of a trial, knowing the proportion that had improvement surpassing the MCII provides useful information on treatment response that complements response criteria such as the ACR20 (10). MCIIs might also be considered as thresholds for early escape in clinical trials. Our results should also be applicable to patients with active RA in observational studies. In clinical practice, patients with improvement that exceeds the MCII who yet report no subjective improvement should signal the clinician to investigate reason for this mismatch, including depression or other situational factors.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Abhijit Dasgupta PhD for statistical advice.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and NIH RO1-AR45177.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

None of the authors has associated commercial interests.

CONTRIBUTORSHIP

M. Ward conceived and designed the study. M. Ward, L. Guthrie, and M. Alba collected the data, and M. Ward did the analysis. M. Ward drafted the manuscript and all authors provided critical review and approval of the final version.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Approved by the NIDDK/NIAMS Institutional Review Board, U.S. National Institutes of Health.

DATA SHARING

Data will be publicly available at the conclusion of the study.

LICENSE

The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for UK Crown Employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd, and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and any other BMJPGL products and to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in our licence.

REFERENCES

- 1.Guyatt GH, Osoba D, Wu AW, et al. Methods to explain the clinical significance of health status measures. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:371–383. doi: 10.4065/77.4.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Katz JN, et al. Looking for important change/difference in studies of responsiveness. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redelemeier DA, Lorig K. Assessing the clinical importance of symptomatic improvements. An illustration in rheumatology. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:1337–1342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells GA, Tugwell P, Kraage GR, et al. Minimum important difference between patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the patient’s perspective. J Rheumatol. 1993;20:557–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kosinski M, Zhao SZ, Dedhiya S, et al. Determining minimally important changes in generic and disease-specific health-related quality of life questionnaires in clinical trials of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:1478–1487. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200007)43:7<1478::AID-ANR10>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tubach F, Ravaud P, Martin-Mola E, et al. Minimum clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state in pain and function in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, chronic back pain, hand osteoarthritis, and hip and knee osteoarthritis: results from a prospective multinational study. Arthritis Care Res. 2012;64:1699–1707. doi: 10.1002/acr.21747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kvamme MK, Kristiansen IS, Lie E, et al. Identification of cutpoints for acceptable health status and important improvement in patient-reported outcomes, in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and ankylosing spondylitis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:26–31. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pope JE, Khanna D, Norrie D, et al. The minimally important difference for the health assessment questionnaire in rheumatoid arthritis clinical practice is smaller than in randomized controlled trials. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:254–259. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aletaha D, Funovits J, Ward MM, et al. Perception of improvement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis varies with disease activity levels at baseline. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61:313–320. doi: 10.1002/art.24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aletaha D, Landewe R, Karonitsch T, et al. Reporting disease activity in clinical trials of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: EULAR/ACR collaborative recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:1360–1364. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.091454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31:315–324. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, et al. Measurement of patient outcomes in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prevoo ML, van’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, et al. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38:44–48. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology. 2003;42:244–257. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aletaha D, Nell VP, Stamm T, et al. Acute phase reactants add little to composite disease activity indices for rheumatoid arthritis: validation of a clinical activity score. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7:R796–R806. doi: 10.1186/ar1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status. Ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10:407–415. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon JS, Hayes S, Constable PDL, et al. What are the 'best' measurements for monitoring patients during short-term second-line therapy? Br J Rheumatol. 1988;27:37–43. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/27.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ward MM. Clinical measures in rheumatoid arthritis: Which are most useful in assessing patients? J Rheumatol. 1994;21:17–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tugwell P, Wells G, Strand V, et al. Clinical improvement as reflected in measures of function and health-related quality of life following treatment with leflunomide compared with methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: sensitivity and relative efficiency to detect a treatment effect in a twelve-month, placebo-controlled trial. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:506–514. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200003)43:3<506::AID-ANR5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhoeven AC, Boers M, van der Linden S. Responsiveness of the core set, response criteria, and utilities in early rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000;59:966–974. doi: 10.1136/ard.59.12.966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranganath VK, Yoon J, Khanna D, et al. Comparison of composite measures of disease activity in an early seropositive rheumatoid arthritis cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1633–1640. doi: 10.1136/ard.2006.065839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bentley MJ, Greenberg JD, Reed GW. A modified rheumatoid arthritis disease activity score without acute-phase reactants (mDAS28) for epidemiological research. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:1607–1614. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.090831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salaffi F, Ciapetti A, Gasparini S, et al. The comparative responsiveness of the patient self-report questionnaires and composite disease indices for assessing rheumatoid arthritis activity in routine care. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2012;30:912–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ward MM. Assessing the relative sensitivity to change of rheumatoid arthritis activity measures: Is the type of treatment an important third variable? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49:1161–1169. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(96)00178-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang B, Lavalley M, Felson DT. The sensitivity to change for lower disease activity is greater than for higher disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:1255–1259. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.092460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawley DJ, Wolfe F. Sensitivity to change of the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) and other clinical and health status measures in rheumatoid arthritis. Results of short-term clinical trials and observational studies versus long-term observational studies. Arthritis Care Res. 1992;5:130–136. doi: 10.1002/art.1790050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aletaha D, Strand V, Smolen JS, et al. Treatment-related improvement in physical function varies with the duration of rheumatoid arthritis: a pooled analysis of clinical trial results. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:238–243. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Katz JN, Larson MG, Phillips CB, et al. Comparative measurement sensitivity of short and longer health status instruments. Med Care. 1992;30:917–925. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199210000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J. Statistical power analyses for the behavioral sciences. Second ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beaton DE, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C. Evaluating changes in health status: Reliability and responsiveness of five generic health status measures in workers with musculoskeletal disorders. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:79–93. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00296-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward MM, Marx AS, Barry NN. Identification of clinically important changes in health status using receiver operating characteristic curves. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:279–284. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00140-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Turner D, Schünemann HJ, Griffith LE, et al. Using the entire cohort in the receiver operating characteristic analysis maximizes precision of the minimal important difference. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:374–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Carpenter J, Bithell J. Bootstrap confidence intervals: when, which, what? A practical guide for medical statisticians. Stat Med. 2000;19:1141–1164. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(20000515)19:9<1141::aid-sim479>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aletaha D, Smolen JS, Ward MM. Measuring function in rheumatoid arthritis: Identifying reversible and irreversible components. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2784–2792. doi: 10.1002/art.22052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perkins NJ, Schisterman EF. The inconsistency of “optimal” cutpoints obtained using two criteria based on the receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:670–675. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O’Dell JR, Mikuls TR, Taylor TH, et al. Therapies for rheumatoid arthritis after methotrexate failure. N Engl J Med. 2013 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1303006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreland LW, O’Dell JR, Paulus HE, et al. A randomized comparative effectiveness study of oral triple therapy versus etanercept plus methotrexate in early aggressive rheumatoid arthritis. The Treatment of Early Aggressive Rheumatoid Arthritis Trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64:2824–2835. doi: 10.1002/art.34498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tubach F, Ravaud P, Beaton D, et al. Minimal clinically important improvement and patient acceptable symptom state for subjective outcome measures in rheumatic disorders. J Rheumatol. 2007;34:1188–1193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wywich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:105–221. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mease PJ, Woolley JM, Bitman B, et al. Minimally important difference of health assessment questionnaire in psoriatic arthritis: relating thresholds of improvement in functional ability to patient-rated importance and satisfaction. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2461–2465. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Gestel AM, Haagsma CJ, van Riel PLCM, et al. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis improvement criteria that include simplified joint counts. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:1845–1850. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199810)41:10<1845::AID-ART17>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Greenberg JD, Harrold LR, Bentley MJ, et al. Evaluation of composite measures of treatment response without acute-phase reactants in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology. 2009;48:686–690. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorensen AA, Howard D, Tan WH, et al. Minimal clinically important difference of 3 patient-rated outcomes instruments. J Hand Surg Am. 2013;38:641–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Adamchic I, Tass PA, Langguth B, et al. Linking the Tinnitus Questionnaire and the subjective Clinical Global Impression: which differences are clinically important? Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-10-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farrar JT, Young JP, Jr, LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94:149–158. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00349-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hägg O, Fritzell P, Nordwall A, et al. The clinical importance of changes in outcome scores after treatment for chronic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2003;12:12–20. doi: 10.1007/s00586-002-0464-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cella D, Eton DT, Lai JS, et al. Combining anchor and distribution-based methods to derive minimal clinically important differences on the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) anemia and fatigue scales. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:547–561. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00529-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward MM, Guthrie LC, Alba M. Dependence of the minimal clinically important improvement on the baseline value is a consequence of floor and ceiling effects and not different expectations of patients. J Clin Epidemiol. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.10.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.