Abstract

Rationale

Degradation of frontocerebellar circuitry is a principal neural mechanism of alcoholism-related executive dysfunctions affecting impulse control and cognitive planning.

Objective

We tested the hypothesis that alcoholic patients would demonstrate compromised dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC)-cerebellar functional connectivity when adjusting their strategies to accommodate uncertain conditions and would recruit compensatory brain regions to overcome ineffective response patterns.

Methods

26 alcoholics and 26 healthy participants underwent functional MRI in two sequential runs while performing a decision-making task. The first run required a response regardless of level of ambiguity of the stimuli; the second run allowed a PASS option (i.e., no response choice), which was useful on ambiguous trials.

Results

Healthy controls demonstrated strong synchronous activity between the dACC and cerebellum while planning and executing a behavioral strategy. By contrast, alcoholics showed synchronous activity between the dACC and the premotor cortex, perhaps enabling successful compensation for accuracy and reaction time in certain conditions; however, a negative outcome of this strategy was rigidity in modifying response strategy to accommodate uncertain conditions. Compared with the alcoholic group, the control group had lower nonplanning impulsiveness, which correlated with using the option PASS to respond in uncertain conditions.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that compromised dACC-cerebellar functional circuitry contributes to recruitment of an alternative network—dACC-premotor cortex—to perform well under low risk, unambiguous conditions. This compensatory network, however, was inadequate to enable the alcoholics to avert making poor choices in planning and executing an effective behavioral strategy in high-risk, uncertain conditions.

Keywords: Alcoholism, Nonplanning Impulsivity, Anterior Cingulate Cortex, Cerebellum

Introduction

Alcoholism affects selective brain structures, their related circuitry, and the selective cognitive functions they subserve (Sullivan et al. 2010; Oscar-Berman and Marinković 2007; Makris et al. 2008). Although the structural changes to the brain and function that occur as consequences of chronic alcohol consumption might be subthreshold for a diagnosable neurological disorder (Pitel et al. 2011), uncomplicated alcoholics demonstrate executive dysfunctions, such as impaired cognitive flexibility in adapting and switching their behavioral strategies to address specific contextual demands (Cunha et al. 2010). Adaptive goal-directed behavior requires a cognitive control system, which monitors performance and compares its outcomes with current goals (Ridderinkhof et al. 2004). The cognitive control system organizes processes such as focusing and shifting attention, inhibiting inappropriate behavioral responses, and optimizing one's behavior in response to environmental feedback (Harding et al. 2005). Chronic, excessive alcohol consumption affects these cognitive control processes, especially during reward-seeking behavior, which is linked to trait disinhibition (Bogg et al. 2012; Schulte et al. 2012; Chen et al. 2007).

The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) is a key brain region enabling cognitive control of adaptive goal-directed behavior (Oscar-Berman and Marinković 2007). The dACC is proposed to be involved in monitoring the context and detecting conflict between competing responses, which leads to signaling executive cognitive control to adjust behaviors and guide performance (Walton et al. 2004). Convergent evidence suggests that the dACC plays a key role in shaping behavioral choices through its functional connectivity with other brain regions (Venkatraman et al. 2009). Previously we reported that the functional connectivity patterns of the dACC could predict the individual's behavioral strategy. The dACC-insula circuit was associated with the adoption of an ambiguity-aversive behavioral strategy, whereas the dACC-cerebellar circuit was recruited as a common neural mechanism in both the subjects who exhibited the ambiguity-approach strategy and those with the ambiguous-aversive strategy (Jung et al. 2014).

In the present study, we focused on the dACC-cerebellar circuit and tested the hypothesis that chronic, excessive alcohol consumption compromises frontocerebellar circuitry, resulting in impaired ability to plan and execute a successful behavioral strategy (Sullivan et al. 2005). Classically, prefrontal damage has been considered to account for the permanent and transient cognitive deficits in chronic alcoholism (Moselhy et al. 2001). It is now recognized, however, that in addition to damage to the frontal lobes themselves, degradation of frontocerebellar circuitry is a principal neural mechanism of alcoholism-related executive dysfunctions affecting impulse control, cognitive planning and attentional set shifting (Chanraud et al. 2013; Sullivan et al. 2005). Cerebellar projections to the frontal lobes that modulate motor and cognitive functions are compromised in alcohol use disorders. Indeed, alterations in the cerebellum can be better predictors of alcoholism-related neuropsychological deficits than those in prefrontal regions (Sullivan et al. 2003).

Functional connectivity based on synchronized activity fluctuations of the functional MRI (fMRI) blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) response has provided a powerful method for mapping frontocerebellar circuits (Krienen and Buckner 2009). Here, we examined the functional connectivity of dACC-cerebellar circuitry in recovering alcoholic patients. Two groups of frontocerebellar circuits are especially relevant in alcoholism (Chanraud et al. 2013): 1) the motor loop linking the motor cortex and the anterior regions of the cerebellum, including lobule V-VI/VIIIB; 2) the cognitive loop connecting the prefrontal cortex and the posterior regions of the cerebellum, including Crus I/II. Although the structural and functional frontocerebellar circuits are distinct (Habas et al. 2009), there is potential for recruitment of intact, neighboring circuitry to compensate for executive impairment. Recovering alcoholics were observed to recruit frontocerebellar circuits parallel to those used by healthy controls to compensate for the compromised cognitive loop (Chanraud et al. 2013). We hypothesized that 1) alcoholic patients would demonstrate compromised dACC-cerebellar functional connectivity when adjusting their strategy to accommodate uncertain conditions; and 2) alcoholic patients would recruit compensatory brain regions that would contribute to their altered response patterns and behavioral strategy.

Methods

Participants

Two groups included 26 alcoholic subjects and 26 age-matched healthy controls (Table 1). All were recruited from the local community through flyers, announcements, or word of mouth and provided written informed consent to participate in this study, which was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Stanford University School of Medicine and SRI international. All participants were administered the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (First et al. 1997) by a clinical research psychologist or research nurse. Exclusion factors were DSM-IV criteria for other Axis I diagnoses or non-alcohol substance abuse. In the alcoholic group, 25 participants met DSM-IV criteria for alcohol dependence and 1 participant met criteria for alcohol abuse. Of those meeting dependence criteria, 24 were in early remission (met criteria within the past 12 months), whereas 1 was in sustained remission (>12 months). The median age of alcoholism onset was 25 years (mean=29.1, SD=13.6). In all, 46% of alcoholic subjects and 0% of healthy controls met DSM-IV dependence for any type of drug dependence. The most common type of drug dependence was cocaine (endorsed by 31% of alcoholics); the median number of year since last used cocaine was 1.3 years (mean=9.5 years, SD=10 years, range=0.5–11.5 years). Other types of drug dependency were amphetamines in 12% and opiods in 12% of alcoholics. The median number of years since amphetamines were last used was 6.5 years (mean=6 years, SD=5.5 years, range=0.5–24.5 years), and for opioids it was 2 years (mean=10 years, SD=14.75 years, range=1.2–27 years). In no case was drug dependence more recent than alcohol dependence. More alcoholic subjects met DSM-IV criteria for nicotine dependence (54% current smokers, 23% past smokers) than did control (12% current smokers, χ2(2)=23.08, P=0.0001).

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Subjects: mean (SD) or frequency count

| Alcoholic Group (N=26) | Control Group (N=26) | T (X2) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.2 (9.5) | 49.5 (11.4) | 0.251 | 0.803 |

| Sex (male) | 18 | 17 | 0.087 | 0.768 |

| Education (years) | 14.0 (2.5) | 15.6 (2.4) | 2.413 | 0.02 |

| Verbal IQa | 100.1 (11.6) | 107.6 (11.8) | 2.063 | 0.045 |

| Lifetime Alcohol Consumption (kg) | 891.4 (567.1) | 44.4 (50.3) | 6.971 | <0.001 |

| Onset age (years) | 29.1 (13.6) | NA | ||

| Duration of Abstinence (days) | 124.3 (93.5) | NA | - | - |

| AUDITb | 25.6 (10.6) | NA | - | - |

Verbal Intelligence Quotient (IQ) was estimated with the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (17)

AUDIT: Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (18)

The alcoholic subjects were abstinent at the time of scanning and showed no withdrawal signs and had a breathalyzer measurement of 0. The range of duration of abstinence was 30-379 days, except for one person, who reported to have had two drinks of beer three days before testing. Participants underwent additional clinical assessments including the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (Wechsler 2001) to assess verbal intelligence, the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (Saunders et al. 1993) to assess severity of alcohol dependent symptoms and a semi-structured interview (Skinner 1982) to quantify lifetime alcohol consumption.

Procedure and stimuli

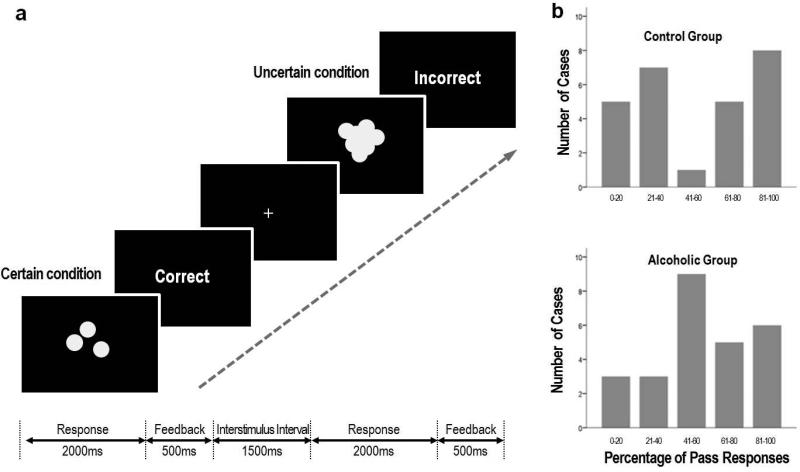

As previously described (Jung et al. 2013), task stimuli consisted of sets of white solid-colored circles on a black background, emulating scattered coins (Figure 1a). Each stimulus was presented for 2000ms; the participants were asked to quickly estimate whether the total number of coins was odd or even. The task consisted of two conditions: 1) a certain condition, in which the participants could easily estimate the correct answer; and 2) an uncertain condition, in which the coins were overlapped and the borders were blurred, so the participants could only make a guess. Depending on the run instructions, the subject could respond “odd, even or PASS,” the latter being neither choice. Each response was immediately followed by feedback, indicating that the response was correct (gain 1 point) or incorrect (lose 1 point).

Figure 1. Odd-Even-Pass Task.

a. The task consisted of two conditions: a certain condition, in which the participants could readily estimate the correct answer; and an uncertain condition, in which the coins were overlapped and the borders were blurred so the participants could only make a guess. The percent of correct feedback of uncertain trial was fixed at 22.5%, regardless of the participant's responses

b. The distribution of Pass responses in the control group was bimodal and divided the participants into two groups: the ambiguity-approach group and the ambiguity-aversive group. By contrast, the alcoholic group represented a unimodal distribution.

Each participant underwent two sequential runs, which were designed in the same manner with the exception that “NO-PASS run 1” allowed only two response options (press 1 if Odd or press 2 if Even), whereas “PASS run 2” provided three response options (press 1 if Odd, press 2 if Even, press 3 if Pass). If the participant chose Pass, the task moved to the next trial without any gain or loss. The participants were informed that the usage of the Pass option was dependent on the participant's decision and no further explicit instructions about how to use the Pass option was given. The uncertain trials were a high-risk condition because the percent of correct feedback was fixed at 22.5%, regardless of the participant's responses. This was determined through a pilot study (Jung et al., 2010) to be an optimal percentage, which is low enough to ensure that the participants could suspect that their correct rate was below 50%, but not so low as to make the participants suspicious that the task was impossible. In this way, the task was designed into two parts: “NO-PASS run 1,” in which the participants could assess the risk of the certain and uncertain trails; and “PASS run 2” in which the participants could modify their performance whether to persist guessing between ODD and EVEN (ambiguity-approach strategy) or to use the Pass option (ambiguity-aversive strategy).

Stimuli were presented via E-prime software (Psychology Software Tools, Inc.), and the participants responded through a keypad connected to the laptop running E-prime. Each task run was composed of 4 certain blocks and 4 uncertain blocks, which were presented in a pseudo-randomized order. Each block consisted of 9 trials. Accuracy and reaction times (RT) were recorded. Prior to the scanning session, participants repeated a practice run until accuracy rate exceeded 90% for the certain trials. The practice run was first rehearsed without a Pass option and then with a Pass option. After the scanning session, impulsivity was measured through the self-report, the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS), which compromises three subscales: 1) Motor Impulsiveness, characterized by acting on the spur of the moment and an inconsistent lifestyle; 2) Cognitive (Attention) Impulsiveness, reflecting difficulty in focusing on the task at hand and involving “thought insertions and racing thoughts;” and 3) Nonplanning Impulsiveness, characterized by lack of planning and cognitive complexity (Patton et al. 1995). These three sub-traits are proposed to be dissociable and related to different cognitive processes subserving executive functions (Kam et al. 2012).

Image acquisition

MR imaging was conducted on a GE (General Electric Medical Systems, Signa, Waukesha, WI) 3T whole body MRI scanner equipped with an 8-channel head coil. Subject motion was minimized by following best practices for head fixation, and structural image series were inspected for residual motion. Whole-brain fMRI data were acquired with a T2*-weighted gradient echo planar pulse sequence (2D axial, TE = 30 ms, TR =2200 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view=240mm, matrix = 64 × 64, slice thickness = 5 mm, skip=0mm, 36 slices). A dual fast spin-echo anatomical scan (2D axial, TE = 17/98 ms; TR =5000 ms, flip angle = 90°, field of view = 240mm, matrix=256 ×256, slice thickness = 5 mm, skip=0mm, 36 slices) was acquired together with the fMRI data. A field map was generated from a gradient recalled echo sequence pair (TE = 3/5 ms, TR = 460 ms, slice thickness = 2.5 mm, skip=0mm, 36 slices) (Pfeuffer et al. 2002). High-order shimming was performed before the functional scans (Kim et al. 2002).

Image pre-processing and fMRI contrast analysis

Spatial preprocessing and statistical analysis of functional images were performed using SPM8 (Wellcome Trust Centre for Neuroimaging; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm). Motion artifacts were assessed in individual subjects by visual inspection of realignment parameter estimations to confirm that the maximum head motion in each axis was less than 2 mm, without any abrupt head motion. Functional images were realigned and unwarped (correction for field distortions) using the gradient echo field maps (constructed from the complex difference image between 2 echoes [3 and 5 ms] of the GREs series). Unwarped functional images were registered to structural images for each subject. The anatomical volume was then segmented into gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. The gray matter image was used for determining the parameters of normalization onto the standard Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) gray matter template. The spatial parameters were then applied to the realigned and unwarped functional volumes that were finally resampled to voxels of 2×2×2mm and smoothed with an 8 mm full-width at half-maximum kernel.

Individual statistics were computed using a general linear model approach (Friston et al. 1995). Statistical preprocessing consisted of high pass filtering at 128 s, low pass filtering through convolution with SPM8 canonical hemodynamic response function and global scaling. A random effect analysis was conducted for group averaging and population interference, where one image per contrast was computed for each subject, and these images were subjected to t-tests, which produced a statistical image for the contrast uncertain>certain in each subject. The contrast uncertain>certain was compared between groups with an uncorrected p-value height threshold of 0.001 and k=20 as extent threshold for the whole brain.

Functional connectivity analyses

For functional connectivity analysis, the dACC seed (a 10mm radius sphere, centered x=6, y=32, z=40) was derived from the overlap significant cluster of the contrast uncertain>certain during the no-PASS run 1 through conjunction analysis. Seed-to-voxel connectivity was measured by correlating the time course of the BOLD activity of each run. Before averaging individual voxel data, the waveform of each brain voxel was filtered using a bandpass filter (0.0083/s <f<Inf) to reduce the effect of low-frequency drift and high-frequency noise. Signals from the ventricular regions and signal from the white matter were removed from the data through linear regression. Connectivity analysis was conducted with the “conn” toolbox (http://www.nitrc.org/projects/conn), implemented in the SPM8. The functional connectivity maps of two groups were compared with an uncorrected p-value height threshold of 0.001 and k=20 as extent threshold for the whole brain.

Statistical analysis

To examine brain-behavior relationships, we extracted the Fisher-transformed Z-value measures of functional connectivity between the dACC seed and the target ROIs that were identified clusters through contrast analysis. For between-group comparisons, behavioral performance and the functional seed-target connectivity across runs were conducted with repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA). Spearman correlation analysis tested relations between functional connectivity, behavioral performance (accuracy rate, number of Pass responses), and clinical characteristics (nonplanning impulsiveness, duration of abstinence). Statistical analyses were conducted by using SPSS (Chicago, IL) with p<0.05 two-tailed.

Results

Use of Pass responses

Participants underwent two sequential runs: NO-PASS run1 and PASS run2. The percentage of Pass responses was highly variable across subjects (0-100%). There was no significant difference of mean percentage of Pass responses between the two groups (alcoholics = 54.4±27.7%, controls =53.7±32.0%; t=0.084, p=0.933). The distribution of Pass responses, however, in the control group represented a bimodal distribution, whereas the alcoholic group represented a unimodal distribution (Figure 1b).

Accuracy and reaction time

The behavioral performances are presented in Table 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups in accuracy under certain conditions (F1, 50=2.972, p=0.091). ANOVA indicated a significant effect of run (F1, 50=9.034, p=0.004) with both groups demonstrating greater accuracy in “PASS run2.” The group-by-run interaction was not significant (F1, 50=2.871, p=0.096). The accuracy of uncertain conditions was predetermined at 22.5% regardless of the responses. There was no statistical difference between the two groups in missing responses (run1: t=−1.342, p=0.186’ run 2: t=−0.816, p-0.419).

Table 2.

Behavioral Performance of Subjects: Mean (SD)

| Control Group (N=26) | Alcoholic Group (N=26) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NO-PASS run 1a | Certain | Accuracy % | 97.6(3.0) | 94.7(5.7) |

| Reaction Time, ms | 1040.5(325.2) | 1071.4(285.7) | ||

| Uncertain | Accuracy, % | 22.5c | 22.5c | |

| Reaction Time, ms | 1325.9(269.6) | 1254.6(283.1) | ||

| PASS run 2b | Certain | Accuracy, % | 98.3(3.3) | 97.2(5.8) |

| Reaction Time, ms | 845.5(162.6) | 907.1(129.9) | ||

| Uncertain | Accuracy, % | 22.5c | 22.5c | |

| Reaction Time, ms | 1253.5(249.4) | 1134.0(234.7) |

When Pass was not provided as an alternative response option

When Pass was provided as an alternative response option

The accuracy of uncertain conditions was predetermined at 22.5% regardless of the participants' responses.

ANOVA revealed no overall difference between the two groups in reaction time (RT, F1, 50=0.023, p=0.880). Significant effect of run (F1, 50=44.798, p<0.001) and condition (F1, 50=180.352, p<0.001) were identified, where faster RTs occurred in “PASS run2” and conditions of certainty. A significant group-by-condition interaction (F1, 50=4.718, p=0.035) indicated that the alcoholic group had slower RT in certain conditions and faster RT in uncertain conditions than the control group.

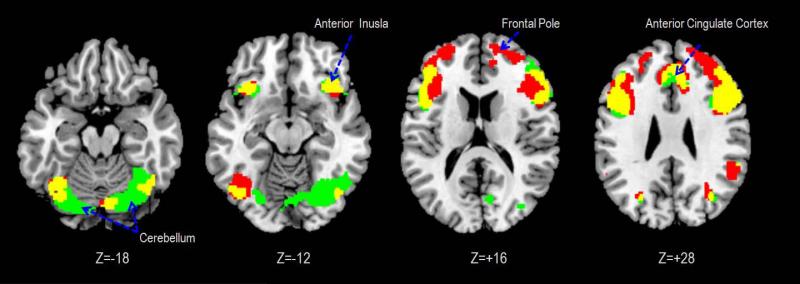

Brain activations associated with uncertainty

In “NO-PASS run 1,” both groups demonstrated significant BOLD responses in the uncertain>certain contrast in the dACC, anterior insula, inferior frontal gyrus and cerebellum (Figure 2). Between-group differences were observed in the frontal pole and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), which demonstrated stronger BOLD responses in the alcoholic group than the control group (Table 3).

Figure 2. Brain regions exhibiting significant activations to uncertainty.

Green: activated only in the Control group; Red: activated only in the Alcoholic group; Yellow: activated in both groups. Statistical inferences were thresholded using an uncorrected p-value height threshold of 0.001 and k=20 as extent threshold for the whole brain.

Table 3.

Brain regions exhibiting significant activations to contrast Uncertain>Certain

| Control+Alcoholica |

Control > Alcoholic |

Control < Alcoholic |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vol | Tmax | x | y | z | Vol | Tmax | x | y | z | Vol | Tmax | x | y | z | |||

| NO-PASS run1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Frontal Pole | Right | 10 | 93 | 4.62 | 14 | 56 | 16 | ||||||||||

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Right | 46 | 26 | 3.71 | 26 | 52 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Anterior Cingulate Cortexb | Right | 32 | 1043 | 5.44 | 6 | 32 | 40 | ||||||||||

| Anterior Insulab | Right | 2868 | 5.67 | 42 | 24 | −10 | |||||||||||

| Left | 1564 | 5.17 | −32 | 22 | −6 | ||||||||||||

| Premotor cortex | Left | 6 | 55 | 3.56 | −38 | 4 | 54 | ||||||||||

| Thalamus | Right | 79 | 3.90 | 12 | −8 | 8 | |||||||||||

| Left | 58 | 3,74 | −10 | −12 | 8 | ||||||||||||

| Inferior Parietal Lobuleb | Right | 40 | 587 | 5.03 | 58 | −46 | 44 | ||||||||||

| Left | 40 | 461 | 4.04 | −42 | −52 | 54 | |||||||||||

| Middle Occipital Gyrus | Right | 19 | 32 | 3.65 | 34 | −70 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Cerebellum , Vermis | Left | 48 | 3.77 | −2 | −60 | −38 | |||||||||||

| Cerebellum VI | Right | 400 | 4.56 | 44 | −58 | −22 | |||||||||||

| Left | 537 | 4.57 | −38 | −62 | −22 | ||||||||||||

| Right | 137 | 3.97 | 10 | −78 | −20 | ||||||||||||

| Cerebellum, crus I | Left | 31 | 3.91 | −12 | −80 | −22 | |||||||||||

| PASS run2 | |||||||||||||||||

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Right | 46 | 23 | 3.51 | 34 | 52 | 16 | ||||||||||

| Left | 46 | 44 | 3.82 | −42 | 36 | 28 | |||||||||||

| Anteior Cingulate Cortex | Right | 32 | 248 | 4.15 | 4 | 22 | 46 | ||||||||||

| Anteior Insula | Left | 173 | 4.02 | −36 | 22 | −8 | |||||||||||

| Inferior Frontal Gyrusb | Right | 44 | 2167 | 5.20 | 44 | 6 | 34 | ||||||||||

| Left | 44 | 405 | 4.33 | −50 | 12 | 28 | |||||||||||

| Posterior Cingulate Cortex | Right | 23 | 82 | 3.90 | 4 | −24 | 28 | ||||||||||

| Inferior Parietal Lobuleb | Left | 40 | 55 | 3.98 | −54 | −44 | 44 | ||||||||||

| Right | 40 | 2238 | 5.01 | 62 | −46 | 30 | |||||||||||

| Right | 40 | 24 | 4.81 | 42 | −54 | 52 | |||||||||||

| Inferior Temporal Gyrus | Right | 37 | 36 | 3.97 | 52 | −60 | −14 | ||||||||||

| Cerebellum Vermis | Right | 21 | 3.58 | 8 | −34 | 12 | |||||||||||

| Cerebellum, VI | Right | 211 | 3.92 | 32 | −62 | −26 | |||||||||||

| Cerebellum, Crus Ib | Left | 677 | 4.98 | −38 | −68 | −24 | |||||||||||

Threshold was uncorrected p<0.001 (Tmax=3.26), kE>20 voxels for the whole brain.

There were no supra-threshold clusters for Control>Alcoholic (run1) and Control<Alcoholic (run2).

Conjunction analysis were conducted.

Regions in bold letters are activations which were thresholded by family-wise error(FEW) corrected p<0.05

In “PASS run 2,” both groups demonstrated significant BOLD responses in the inferior frontal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and cerebellum (Cbll) in the uncertain>certain comparison. Between-group differences indicated stronger BOLD responses in the Cbll of the control group than the alcoholic group.

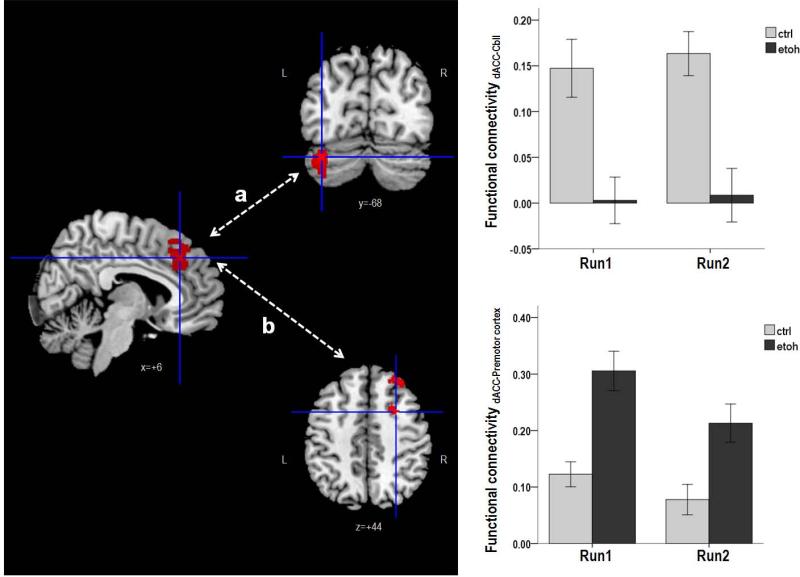

Functional connectivity of the dACC

In “NO-PASS run 1,” the control group demonstrated synchronized activity between the dACC and the left Cbll lobule VI (Figure 3a). By contrast, the dACC activity synchronized with activations in the DLPFC, premotor cortex, and supplementary motor area in the alcoholic group (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Between group comparison of dACC functional connectivity.

a. The dACC-cerebellum functional connectivity was significantly stronger in the control group than the alcoholic group (F1, 50=19.457; p<0.001). There was no significant effect of run on the functional connectivity (F1, 50=0.299, p=0.587), and there was no significant interaction between run and group (F1, 50=0.068, p=0.795).

b. The dACC-premotor cortex functional connectivity was significantly stronger in the alcoholic group than the control group (F1, 50=20.464, p<0.001). There was a significant effect of run on the functional connectivity (F1, 50=8.631, p=0.005) but no significant interaction of run and group (F1, 50=1.039, p=0.313). (Sidebars represent +/− 1 standard error).

In “PASS run 2,” the control group demonstrated synchronized activity between the dACC and the left Cbll Crus I/II. By contrast, the alcoholics showed greater synchrony than controls in dACC activity with activations in the premotor cortex, supplementary motor area, postcentral gyrus, precuneus, and the middle temporal gyrus (Table 4).

Table 4.

Brain regions exhibiting functional connectivity with the dACC seed (6, 32, 40)

| Region | BA | Control > Alcoholic |

Control < Alcoholic |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kE | Tmax | x | y | z | kE | Tmax | x | y | z | |||

| NO-PASS run 1a | ||||||||||||

| Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex | Right | 9 | 49 | 3.88 | 32 | 36 | 46 | |||||

| Premotor Cortex | Right | 6 | 45 | 4.00 | 26 | 8 | 44 | |||||

| Left | 6 | 67 | 4.18 | −26 | 0 | 36 | ||||||

| Supplementary Motor Area | Right | 6 | 25 | 3.71 | 10 | 4 | 50 | |||||

| Left | 6 | 114 | 4.08 | −14 | 8 | 40 | ||||||

| Cerebellum, Lobule VI | Right | 39 | 4.38 | 30 | −4 | −3 | ||||||

| PASS run 2b | ||||||||||||

| Premotor Cortex | Right | 6 | 23 | 3.79 | 38 | −10 | 56 | |||||

| Supplementary Motor Area | Right | 6 | 97 | 4.70 | 0 | −14 | 72 | |||||

| Postcentral Gryus | Right | 3 | 119 | 4.02 | 48 | −14 | 30 | |||||

| Left | 1 | 40 | 3.80 | −26 | −42 | 72 | ||||||

| Precuneus | Left | 5 | 85 | 4.39 | −8 | −44 | 78 | |||||

| Middle Temporal Gyrus | Right | 21 | 31 | 4.07 | 66 | −52 | 14 | |||||

| Right | 39 | 53 | 4.01 | 58 | −68 | 20 | ||||||

| Cerebellum, Crus I/II | Left | 249 | 4.61 | −36 | −7 | −2 | ||||||

Threshold was uncorrected p<0.001 (Tmax=3.26), kE>20 voxels for the whole brain.

When Pass was not provided as an alternative response option

When Pass was provided as an alternative response option

Functional Connectivity and Behavioral Responses

In the control group, stronger synchronous activity between the dACC and left Cbll crus I correlated with greater accuracy (rho=0.645, p<0.001) and faster reaction time (rho=-0.517, p=0.007) in certain conditions (Supplementary Figure 1). By contrast, faster reaction time correlated with stronger synchronous activity between dACC and premotor cortex in the alcoholic group (rho=-0.488, p=0.011).

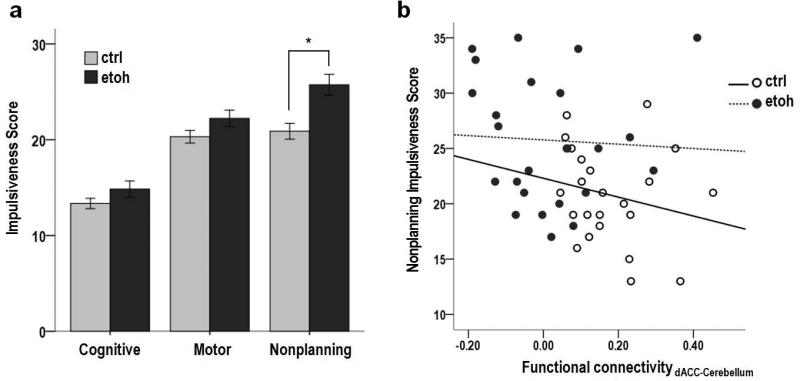

Nonplanning Impulsiveness and Behavioral Responses

Nonplanning impulsiveness was significantly higher in the alcoholic group than the healthy control group (t=3.317, p=0.002; Figure 4a); however, there was no significant difference between the two groups in cognitive impulsiveness and motor impulsiveness. Within the control group, lower nonplanning impulsiveness correlated with greater accuracy (rho=−0.497, p=0.010) and faster reaction time (rho=0.461, p=0.018) in certain conditions and more Pass responses in uncertain conditions (rho=−0.392, p=0.048).

Figure 4. Non-planning Impulsiveness.

a. Non-planning impulsiveness was significantly higher in the alcoholic group compared to the healthy control group; however, there was no significant difference between the two groups in cognitive impulsiveness and motor impulsiveness. (Sidebars represent +/− 1 standard error).

b. Across the entire sample, lower non-planning impulsiveness correlated with stronger dACC-Cerebellum functional connectivity (rho=rho=-0.345, p=0.012). This correlation was neither significant within the alcoholic group (rho=-0.144, p=0.481) nor control group (rho=−0.328, p=0.102).

Across the entire sample, lower nonplanning impulsiveness correlated with stronger synchronous activity between the dACC and left Cbll crus I (rho=−0.345, p=0.012; Figure 4b), whereas greater nonplanning impulsiveness correlated with stronger synchronous activity between the dACC and right premotor cortex (rho=0.372, p=0.007). Within the alcoholic group, longer duration of abstinence correlated with stronger synchronous activity between the dACC and left Cbll crus I (rho=0.407, p=0.039).

Discussion

Our findings support the possibility that alcoholics recruited dACC-cortical circuitry to compensate for disrupted frontocerebellar circuitry. Despite comparable performance of the alcoholics and healthy controls under conditions of certainty, the inferred compensatory activity was ineffective in enabling alcoholics to plan and execute an effective strategy of using the Pass option under uncertain, high-risk situations. In contrast with the alcoholic group, the control group demonstrated strong synchronous activity between the dACC and Cbll and had lower nonplanning impulsiveness, which correlated with more Pass responses in uncertain conditions.

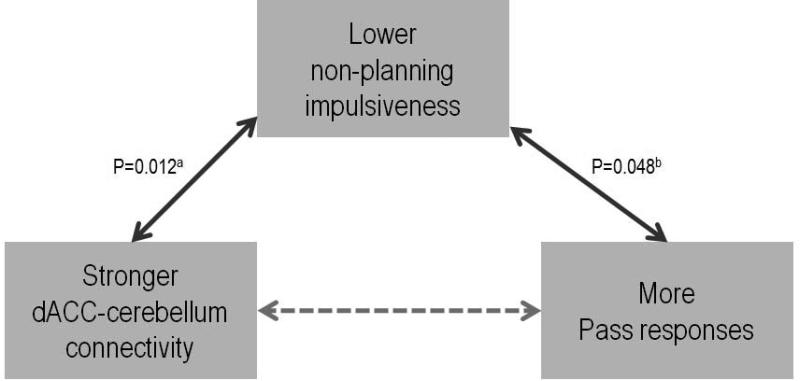

Impulsivity is a heterogeneous construct. Within the framework of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, three dissociable subtraits of impulsivity can be measured: cognitive (attentional) impulsiveness, motor impulsiveness, and nonplanning impulsiveness (Patton et al. 1995). The response pattern observed during “PASS run 2” showed a lack of planning by the alcoholics, consistent with the nonplanning impulsivity subtrait. This lack of planning occurred despite experience with the “NO-PASS run 1,” which provided experience to participants who were able to discern a plan for enhancing their percentage of correct responses when given the option to PASS on ambiguous trials. Regarding the PASS option, the healthy controls used one of two strategies: whether to use or not to use the PASS option. Unlike the controls, most of the alcoholics did not favor one strategy over another, but rather selected the PASS option randomly. We propose that non-planning impulsiveness might be a mediator between stronger dACC-cerebellum connectivity and more PASS responses (Figure 5), which proved to be a good strategy in controls. The anterior cingulate cortex is a key region of the planning network, which contributes to preparatory processes, including goal determination, target identification, and selection (Glover et al. 2012). In our study, greater functional connectivity between the dACC and the Cbll correlated with greater accuracy and faster reaction time in trials of high certainty and with more use of the PASS option in uncertain trials, as evidenced in the controls. The alcoholics were successful in compensating for accuracy and reaction time under conditions of certainty but were unsuccessful in adjusting their current strategy to accommodate uncertain conditions. Taken together, these findings indicate that the compromised dACC-cerebellar functional circuitry contributed to the alcoholics' impaired ability to plan and execute an effective behavioral strategy during run 2 when given the opportunity to choose PASS.

Figure 5. Non-planning impulsiveness, dACC connectivity and PASS responses.

Non-planning impulsiveness might be a mediator between stronger dACC-cerebellum connectivity and more PASS responses. (aBased on the correlation across the entire sample; bBased on the correlation in the control group only).

Previous studies demonstrated that alcoholics with compromised corticocerebellar circuitry recruited additional brain areas while engaged in cognitive tasks to compensate for executive shortcomings (Sullivan et al. 2003). Yet, in response to uncertain relative to certain trials, the alcoholics, unlike the controls, did not show greater activity in the cerebellum. Rather, alcoholics demonstrated significant activity in the DLPFC. The DLPFC is part of the frontoparietal network, which is engaged in initiating and adapting control on a trial-by-trial basis, whereas the ACC controls goal-directed behavior through the stable maintenance of task sets, that is, across trials (Dosenbach et al. 2007). That the alcoholic group demonstrated normal behavioral performance under certain conditions suggests a compensatory role of the DLPFC and prefrontal motor activity for the impaired frontocerebellar circuit in alcoholics (Chanraud et al. 2013). Recruitment of dACC-premotor cortex circuitry, however, was not successful in enhancing performance in uncertain conditions, as the alcoholics only randomly used the Pass option.

The ACC, which is integrated with the medial prefrontal cortex, is implicated in generating a cluster of event-related brain potential responses while individuals monitor behavioral and environmental consequence (van Noordt et al. 2012). Converging evidence suggests that these activity patterns during performance monitoring are influenced not only by the task context but also by individual differences, such as temperament, personality, and clinical symptomatology (van Noordt et al. 2012). Individuals with high nonplanning impulsivenss have more difficulty in complex mental activities involving detection of conflicts between response options and, therefore, avoid situations that require choosing between conflicting behavioral options (Kam et al. 2012). Alcoholics, who had higher levels of impulsivity showed smaller outcome-related positivity signals at the ACC and demonstrated risk-taking decisions during a gambling task (Kamarajan et al. 2010). Taken together, it is feasible to link alcoholism with greater nonplanning impulsiveness and executive dysfunction, such as attenuated learning of selecting advantageous options over disadvantageous ones (Moeller et al. 2007). This possibility is consistent with our findings that the alcoholics were rigid in incorporating outcomes without modifying the ongoing, now irrelevant strategy (Lee et al. 2013), similar to the behavior observed under conditions eliciting proactive interference (De Rosa et al. 2003).

Within the alcoholic group, longer duration of abstinence correlated with stronger synchronous activity between the dACC and cerebellum but did not with lower impulsiveness. Repeated cycles of alcohol intoxication and abstinence resulted in increased impulsivity (Irimia et al., 2013). On the other hand, high impulsivity has been found in families with alcoholism, suggesting a genetic link between alcoholism and impulsivity (Saunders et al., 2008; DeVito et al., 2013). Therefore, the high impulsivity of our alcoholic group could be regarded both as a state consequence of chronic alcohol consumption and as an inherited trait temperament.

There are several limitations in this study. The control group demonstrated a bimodal distribution of PASS responses and, therefore, could be divided into two groups: a high-PASS group and a low-PASS group. Although the group differences were more apparent in the high-PASS group, the low-PASS group also differed from the alcoholic groups in non-planning impulsiveness and dACC functional connectivity (Supplementary Figure2). Another limitation is that half of alcoholic group reported a history of comorbid substance use in addition to alcohol, which might have confounded our findings; however, the correlation between longer duration of alcohol abstinence and stronger dACC connectivity implies that the effect of alcohol abuse was a main factor.

In summary, our findings show that the inability to plan and execute an effective strategy under uncertain, high-risk situations is linked to disrupted frontocerebellar circuitry in alcoholics. The persistent alcohol-seeking behavior, even when confronted with seriously negative adverse consequences, might be related to this impaired ability to switch from a predominant strategy and make use of available alternatives to make better choices.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank William Hawkes for data collection and analysis. Research was supported by NIH grant AA010723, AA012388, AA017168, AA017923.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bogg T, Fukunaga R, Finn PR, Brown JW. Cognitive control links alcohol use, trait disinhibition, and reduced cognitive capacity: Evidence for medial prefrontal cortex dysregulation during reward-seeking behavior. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122(1-2):112–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanraud S, Pitel AL, Müller-Oehring EM, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Remapping the brain to compensate for impairment in recovering alcoholics. Cereb Cortex. 2013;23(1):97–104. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhr381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AC, Porjesz B, Rangaswamy M, Kamarajan C, Tang Y, Jones KA, Chorlian DB, Stimus AT, Begleiter H. Reduced frontal lobe activity in subjects with high impulsivity and alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(1):156–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00277.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha PJ, Nicastri S, de Andrade AG, Bolla KI. The frontal assessment battery (FAB) reveals neurocognitive dysfunction in substance-dependent individuals in distinct executive domains: Abstract reasoning, motor programming, and cognitive flexibility. Addict Behav. 2010;35(10):875–81. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rosa E, Sullivan EV. Enhanced release from proactive interference in nonamnesic alcoholic individuals: implications for impaired associative binding. Neuropsychology. 2003;17(3):469–81. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vito EE, Meda SA, Jiantonio R, Potenza MN, Krystal JH, Pearlson GD. Neural correlates of impulsivity in healthy males and females with family histories of alcoholism. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(10):1854–63. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Miezin FM, Cohen AL, Wenger KK, Dosenbach RA, Fox MD, Snyder AZ, Vincent JL, Raichle ME, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(26):11073–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, National Institute of Mental Health . User's guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders: SCID-I clinician version. American Psychiatric Press; Washington, DC: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Holmes AP, Poline JB, Grasby PJ, Williams SC, Frackowiak RS, Turner R. Analysis of fMRI time-series revisited. Neuroimage. 1995;2(1):45–53. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1995.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover S, Wall MB, Smith AT. Distinct cortical networks support the planning and online control of reaching-to-grasp in humans. Eur J Neurosci. 2012;35(6):909–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2012.08018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habas C, Kamdar N, Nguyen D, Prater K, Beckmann CF, Menon V, Greicius MD. Distinct cerebellar contributions to intrinsic connectivity networks. J Neurosci. 2009;29(26):8586–94. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1868-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding IH, Solowij N, Harrison BJ, Takagi M, Lorenzetti V, Lubman DI, Seal ML, Pantelis C, Yücel M. Functional connectivity in brain networks underlying cognitive control in chronic cannabis users. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(8):1923–33. doi: 10.1038/npp.2012.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irimia C1, Wiskerke J, Natividad LA, Polis IY, de Vries TJ, Pattij T, Parsons LH. Increased impulsivity in rats as a result of repeated cycles of alcohol intoxication and abstinence. Addict Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1111/adb.12119. doi: 10.1111/adb.12119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YC, Ku J, Namkoong K, Lee W, Kim SI, Kim JJ. Human orbitofrontalstriatum functional connectivity modulates behavioral persistence. Neuroreport. 2010;21(7):502–6. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283383482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung YC, Schulte T, Müller-Oehring EM, Hawkes W, Namkoong K, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Synchrony of Anterior Cingulate Cortex and Insular-Striatal Activation Predicts Ambiguity Aversion in Individuals with Low Impulsivity. Cereb Cortex. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht008. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kam JW, Dominelli R, Carlson SR. Differential relationships between sub-traits of BIS-11 impulsivity and executive processes: An ERP study. Int J Psychophysiol. 2012;85(2):174–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarajan C, Rangaswamy M, Tang Y, Chorlian DB, Pandey AK, Roopesh BN, Manz N, Saunders R, Stimus AT, Porjesz B. Dysfunctional reward processing in male alcoholics: an ERP study during a gambling task. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(9):576–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Adalsteinsson E, Glover GH, Spielman DM. Regularized higher-order in vivo shimming. Magn Reson Med. 2002;48(4):715–722. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krienen FM, Buckner RL. Segregated fronto-cerebellar circuits revealed by intrinsic functional connectivity. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19(10):2485–97. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Lee E, Ku J, Yoon K, Namkoong K, Jung YC. Disruption of orbitofrontostiatal functional connectivity underlies maladaptive persistent behaviors in alcohol-dependent patients. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(3):266–72. doi: 10.4306/pi.2013.10.3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makris N, Oscar-Berman M, Jaffin SK, Hodge SM, Kennedy DN, Caviness VS, Marinkovic K, Breiter HC, Gasic GP, Harris GJ. Decreased volume of the brain reward system in alcoholism. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64(3):192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Steinberg JL, Lane SD, Buzby M, Swann AC, Hasan KM, Kramer LA, Naravana RA. Diffusion tensor imaging in MDMA users and controls: association with decision making. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33(6):777–89. doi: 10.1080/00952990701651564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moselhy HF, Georgiou G, Kahn A. Frontal lobe changes in alcoholism: a review of the literature. Alcohol Alcohol. 2001;36(5):357–68. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/36.5.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oscar-Berman M, Marinković K. Alcohol: effects on neurobehavioral functions and the brain. Neuropsychol Rev. 2007;17(3):239–57. doi: 10.1007/s11065-007-9038-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin Psycho. 1995;51(6):768–74. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitel AL, Zahr NM, Jackson K, Sassoon SA, Rosenbloom MJ, Pfefferbaum A, Sullivan EV. Signs of preclinical Wernicke's encephalopathy and thiamine levels as predictors of neuropsychological deficits in alcoholism without Korsakoff's syndrome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36(3):580–8. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeuffer J, Van de Moortele PF, Ugurbil K, Hu X, Glover GH. Correction of physiologically induced global off-resonance effects in dynamic echo-planar and spiral functional imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(2):344–353. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, Ullsperger M, Crone EA, Nieuwenhuis S. The role of the medial frontal cortex in cognitive control. Science. 2004;306(5695):443–447. doi: 10.1126/science.1100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption II. Addiction. 1993;88(12):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders B1, Farag N, Vincent AS, Collins FL, Jr, Sorocco KH, Lovallo WR. Impulsive errors on a Go-NoGo reaction time task: disinhibitory traits in relation to a family history of alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(5):888–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00648.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte T, Müller-Oehring EM, Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. Synchrony of corticostriatal-midbrain activation enables normal inhibitory control and conflict processing in recovering alcoholic men. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;71(3):269–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner HA. Development and validation of a lifetime alcohol consumption assessment procedure. Addiction Research Foundation; Toronto, Canada: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV. Compromised pontocerebellar and cerebellothalamocortical systems: speculations on their contributions to cognitive and motor impairment in nonamnesic alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(9):1409–19. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000085586.91726.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Harding AJ, Pentney R, Dlugos C, Martin PR, Parks MH, Desmond JE, Chen SH, Pryor MR, De Rosa E, Pfefferbaum A. Disruption of frontocerebellar circuitry and function in alcoholism. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(2):301–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000052584.05305.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A. Neurocircuitry in alcoholism: a substrate of disruption and repair. Psychopharmacology. 2005;180(4):583–94. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan EV, Harris RA, Pfefferbaum A. Alcohol's Effects on Brain and Behavior. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(1):127–43. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Noordt SJ, Segalowitz SJ. Performance monitoring and the medial prefrontal cortex: a review of individual differences and context effects as a window on self-regulation. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:197. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2012.00197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatraman V, Rosati AG, Taren AA, Huettel SA. Resolving response, decision, and strategic control: evidence for a functional topography in dorsomedial prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2009;29(42):13158–64. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2708-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton ME, Devlin JT, Rushworth MF. Interactions between decision making and performance monitoring within prefrontal cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(11):1259–65. doi: 10.1038/nn1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Test of Adult Reading. Pearson Education; San Antonio, TX: 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.