Abstract

Purpose

Activating mutations in the RAS oncogene occur frequently in human leukemias. Direct targeting of RAS has proven to be challenging, although targeting of downstream RAS mediators, such as MEK, is currently being tested clinically. Given the complexity of RAS signaling, it is likely that combinations of targeted agents will be more effective than single agents.

Experimental Design

A chemical screen using RAS-dependent leukemia cells was developed to identify compounds with unanticipated activity in the presence of a MEK inhibitor, and led to identification of inhibitors of IGF-1R. Results were validated using cell-based proliferation assays and apoptosis, cell cycle, and gene knockdown assays, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting, and a non-invasive in vivo bioluminescence model of acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Results

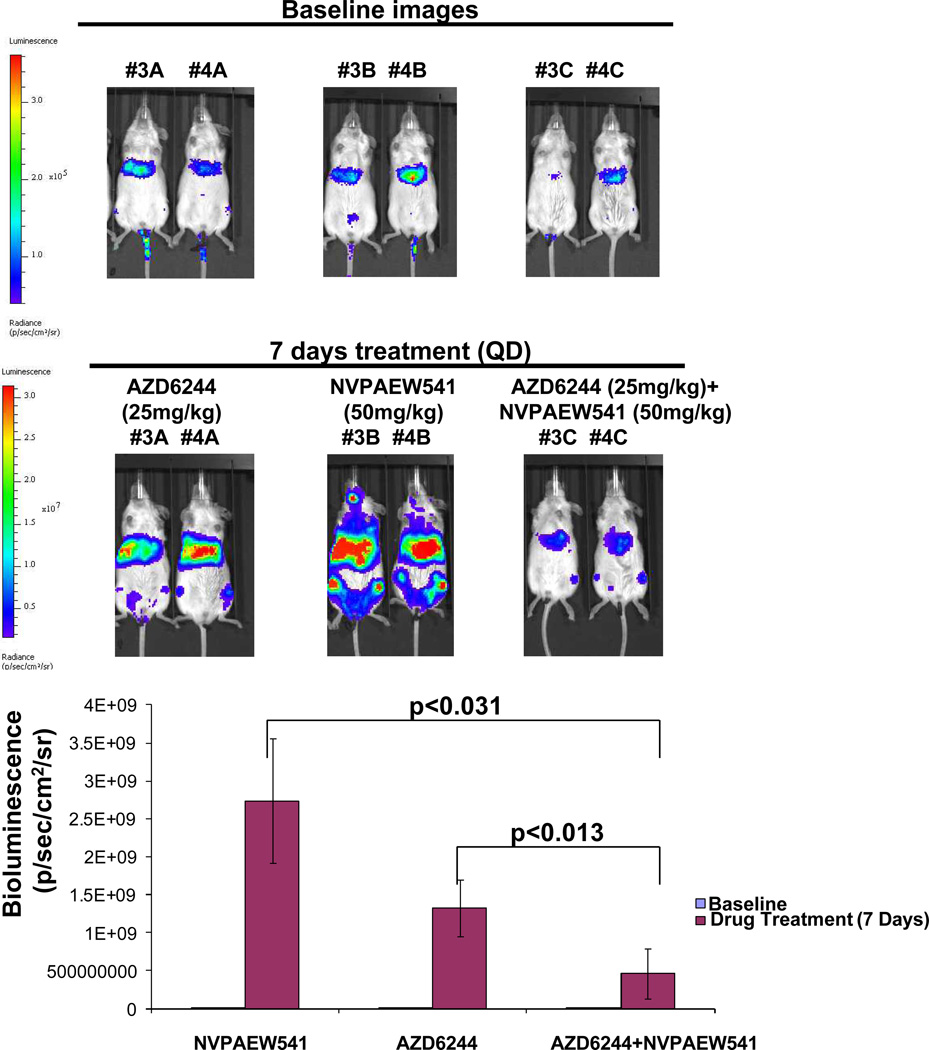

Mechanistically, IGF-1R protein expression/activity was substantially increased in mutant RAS-expressing cells, and suppression of RAS led to decreases in IGF-1R. Synergy between MEK and IGF-1R inhibitors correlated with induction of apoptosis, inhibition of cell cycle progression, and decreased phospho-S6 and phospho-4E-BP1. In vivo, NSG mice tail vein-injected with OCI-AML3-luc+ cells showed significantly lower tumor burden following one week of daily oral administration of 50 mg/kg NVP-AEW541 (IGF-1R inhibitor) combined with 25 mg/kg AZD6244 (MEK inhibitor), as compared to mice treated with either agent alone. Drug combination effects observed in cell-based assays were generalized to additional mutant RAS-positive neoplasms.

Conclusions

The finding that downstream inhibitors of RAS signaling and IGF-1R inhibitors have synergistic activity warrants further clinical investigation of IGF-1R and RAS signaling inhibition as a potential treatment strategy for RAS-driven malignancies.

Keywords: acute myeloid leukemia, RAS mutations, IGF-1R, synergy, MEK

Introduction

RAS genes, which are the most frequent targets of dominant somatic mutations in human malignancies, encode a family of proteins (H-RAS, N-RAS, K-RAS) (reviewed in1), and it is estimated that 20–25% of AML patients have a RAS mutation2. Of relevance, transplantation of mice with bone marrow transduced with retroviral vectors encoding oncogenic KRAS or NRAS has been shown to lead to AML3–5.

Mediation of the effects of RAS by major signaling pathways such as PI3K//PTEN/AKT/mTOR and Raf/MEK/ERK has prompted the development of targeted inhibitors of these pathways as a strategy to treat mutant RAS-driven malignancies. Despite its prevalence and significance with respect to transformation, direct molecular inhibition of mutant forms of RAS has thus far been difficult due to its biochemistry and structure6, although KRAS (G12C) mutant-specific inhibitors, which depend on mutant cysteine for their selective inactivation of this mutant, have recently been reported and are in early stages of development7–8. So far, attempts to block RAS function, including inhibition of kinases associated with downstream effector pathways such as PI3K, AKT, MEK, and mTOR, have shown fairly modest clinical efficiency9–10.

Inhibition of MEK, a prominent downstream effector of RAS, has been tested in mouse models of AML initiated by hyperactive RAS, resulting in initial response followed by relapse despite continued treatment, apparently by outgrowth of pre-existing drug-resistant clones11. The development of "first generation" allosteric MEK inhibitors, such as CI-1040 and PD0325901, was halted due to toxicity and minimal activity in RAS mutant tumors12.

While newer MEK inhibitors, such as AZD624413, show less toxicity and more effectiveness against RAS mutant-positive solid tumors, it is still unclear whether they are better than standard therapies. For example, a Phase II trial of AZD6244 for advanced AML patients showed only transient and modest effectiveness14. As the limited efficacy of inhibitors of RAF/MEK/ERK signaling or PI3K/AKT in mutant RAS-positive cancer is believed to be due to negative feedback loops and compensatory activation of the different signaling pathways, the simultaneous testing of inhibitors of multiple effectors in mutant RAS-positive cancers is reasonable.

To address this, we designed a chemical screen to identify agents capable of potentiating the activity of the MEK inhibitor, AZD6244, against mutant RAS-dependent AML cells. In addition to the identification of inhibitors of well-known downstream mediators of RAS signaling, including inhibitors of mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling, the chemical screen also led to the identification of the small molecule inhibitor, GSK1904529A, which selectively inhibits IGF-1R with nanomolar potency and which exhibits potent antitumor activity15. This finding prompted investigation of underlying mechanism(s) of synergy between IGF-1R inhibition and MEK inhibition against mutant RAS-positive AML, as well as further exploration of IGF-1R as a potential therapeutic target for this disease.

Materials and Methods

LINCS library chemical screen

We designed a chemical screen utilizing the kinase inhibitor-focused library, LINCS, to identify selective kinase inhibitors capable of synergizing with the MEK inhibitor, AZD6244, against mutant NRAS-driven cells (see schematic, Supplementary Figure 1). The LINCS library is available from Harvard Medical School/NIH LINCS program (https://lincs.hms.harvard.edu/) and contains 202 known selective and potent kinase inhibitors.

Cell lines and cell culture

IL-3–dependent murine Ba/F3 cells, cultured with 3 ng/mL of mIL-3, were transduced with NRAS G12D– or KRAS G12D containing murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviruses harboring an IRES-GFP. After withdrawal of mIL-3, these cell lines became growth factor-independent.

The human, mutant NRAS-expressing AML line, OCI-AML3, and mutant KRAS-expressing AML lines, SKM-1 (KRAS K117N), NOMO-1 (KRAS G13D), and NB4 (KRAS A18D), were obtained from Dr. Gary Gilliland. The wild-type (wt) RAS-expressing line, HEL, and mutant NRAS-positive line, HL60, were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (Manassas, VA, USA). Wt RAS-positive MOLM1416 was provided by Dr. Scott Armstrong and transduced with the FUW-Luc-mCherry-puro lentivirus17.

FLT3-ITD-containing MSCV retroviruses were transfected into the IL-3-dependent murine hematopoietic cell line Ba/F3 as previously described18. Ba/F3.p210 cells were obtained by transfecting the IL-3-dependent marine hematopoietic Ba/F3 cell line with a pGD vector containing p210BCR-ABL (B2A2) cDNA19–21.

Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D, Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D, HEL, MOLM14, HL60, NOMO-1, NB4, and SKM-1 cells were cultured with 5% CO2 at 37°C, at a concentration of 2×105 to 5×105 in RPMI (Mediatech, Inc., Herndon, VA) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and supplemented with 2% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. OCI-AML3 cells were cultured in alpha MEM media (Mediatech, Inc, Herndon, VA) with 10% FBS and supplemented with 2% L-glutamine and 1% pen/strep. Parental Ba/F3 cells were cultured in RPMI with 10% FBS and supplemented with 2% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomcyin, as well as 15% WEHI-conditioned medium (as a source of IL-3).

We have authenticated the following cell lines through cell line short tandem repeat (STR) profiling (DDC Medical, Fairfield, OH): MOLM14, NOMO-1, HEL, SKM-1, OCI-AML3, and NB4. All cell lines matched >80% with lines listed in the DSMZ Cell Line Bank STR Profile Information.

Chemical compounds and biologic reagents

GSK1904529A, AZD6244, PD0325901, GSK2126458, GSK1120212, AZD8330, PI-103, and ZSTK474 were purchased from MedChem Express Co. Ltd. NVP-AEW541 was synthesized by Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland, and was dissolved in DMSO to obtain a 10 mM stock solution. Serial dilutions were then made, to obtain final dilutions for cellular assays with a final concentration of DMSO not exceeding 0.1%.

Proliferation studies, apoptosis assays, and cell cycle analysis

The trypan blue exclusion assay has been previously described22 and was used for quantification of cells prior to seeding for Cell Titer Glo assays. The Cell Titer Glo assay (Promega, Madison, WI) was used for proliferation studies and carried out according to manufacturer instructions. Cell viability is reported as percentage of control (untreated) cells, and error bars represent the standard error of the mean for each data point. Programmed cell death of inhibitor-treated cells was determined using the Annexin-V-Fluos Staining Kit (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, IN), as previously described22. Cell cycle analysis was carried out via propidium iodide staining and FACS analysis.

Mononuclear Cells

Mononuclear cells were purchased from STEMCELL Technologies (Vancouver, BC, Canada) and cultured in the presence of DMEM with 10% FBS and supplemented with 2% L-glutamine and 1% pen-strep.

Antibodies, immunoblotting, and immunoprecipitation

The following antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA): Phospho-4E-BP1 (S65) (rabbit, #9451), phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr37/46) (236B4) (rabbit mAb #2855), and total 4E-BP1 (53H11) (rabbit mAb, #9644) were used at 1:1000. Phospho-AKT (Ser 473) (D9E) XP(R) (rabbit mAb, #4060) and total AKT (rabbit, #9272) were used at 1:1000. Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (T202/Y204) (rabbit, #9101) and total p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (3A7) (mouse, #9107) were used at 1:1000. Phospho-S6 ribosomal protein (S235/236)(D57.2.2E) XP (R) (rabbit mAb, #4858) was used at 1:1000. Total S6 ribosomal protein (SG10) (rabbit mAb, #2217) was used at 1:1000. Phospho-IGF-1Rβ (Y1135/1136/InsRbeta) (19H7) (rabbit mAb, #3024) was used at 1:1000 in the presence of 5% BSA. Total IGF-1Rβ (D23H3) XP(R) (rabbit mAb, #9750) was used at 1:1000. β-tubulin (rabbit, #2146) was used at 1:1000. Anti-GAPDH (D16H-11) XP (R) (rabbit mAb, #5174) was used at 1:1000.

Anti-c-N-ras (Ab-1) (mouse, F155–227) was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA) and used at 1:300. Total IGF-1Rα (N-20): SC-712 (rabbit) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX) and used at 1:1000. Anti-β-actin (A1978, clone AC-15) (mouse) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and used at 1:1000. Anti-KRAS (mouse, ab55391) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and used at 1:500.

Protein lysate preparation and immunoblotting were carried out as previously described22.

Drug combination studies

For drug combination studies, single agents were added simultaneously at fixed ratios to cells. Cell viability was determined using the Trypan Blue exclusion assay to quantify cells for cell seeding, and Cell Titer Glo for proliferation studies. Cell viability was expressed as the function of growth affected (FA) drug-treated versus control cells; data were analyzed by Calcusyn software (Biosoft, Ferguson, MO and Cambridge, UK), using the Chou-Talalay method23. The combination index=[D]1 /[Dx]1 + [D]2/[Dx]2, where [D]1 and [D]2 are the concentrations required by each drug in combination to achieve the same effect as concentrations [Dx]1 and [Dx]2 of each drug alone.

Knockdown (KD) of genes by shRNA

pLKO.1puro lentiviral shRNA vector particles against KRAS and IGF-1R were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Cells were incubated with the viral particles in the presence of 8 µg/ml Polybrene for 24 hours, and the cells were selected with 1–2 µg/ml puromycin for 72 hours. Following selection, cells were used for the studies described.

The sequence of shRNA are follows:

GFP : ACAACAGCCACAACGTCTATA

IGF1 CCTTAACTGACATGGGCCTTT

IGF2 GCCGAAGATTTCACAGTCAAA

KRAS3 GCAGACGTATATTGTATCATT

While KD of RAS and IGF-1R inhibited the growth of mutant KRAS-expressing cells (data not shown), as compared to GFP control, it did not inhibit growth to the extent of prohibiting analysis of proliferation or validation of gene knock down by western analysis. KD of RAS in HEL cells did not inhibit the growth of these cells (data not shown).

In vivo model of mutant NRAS-positive leukemia

Cells were transduced with a retrovirus encoding firefly luciferase (MSCV-Luc), and selected with neomycin to produce OCI-AML3-luc+ cells. Six week-old female NSG mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). A total of 1.5 × 106 OCI-AML3- luc+ cells were administered by tail-vein injection. Mice were imaged and total body luminescence was quantified as previously described22. One week after inoculation, treatment cohorts with matched tumor burden were established. Cohorts of mice were treated with oral administration of 50 mg/kg NVP-AEW541 per day, 25 mg/kg AZD6244 per day, or a combination of both. AZD6244 was reconstituted in 0.5% methylcellulose (Fluka) and 0.4% polysorbate (Tween80; Fluka). NVP-AEW541 was dissolved in one part N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone and then diluted with nine parts PEG300. Tumor burden was assessed by serial bioluminescence imaging. Spleens were dissected and measured one week following the last imaging point (which was following 7 days of drug treatment). Major tissues were preserved in 10% formalin for histopathologic analysis. Studies were performed with Animal Care and Use Committee protocols at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute.

AML patient cells

Mononuclear cells were isolated from samples from AML patients identified as harboring mutant NRAS. Cells were tested in liquid culture (DMEM, supplemented with 20% FBS) in the presence of different concentrations of single and combined agents. All blood and bone marrow samples from AML patients were obtained under approval of the Dana Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board.

Results

Inhibitors of PI3K and mTOR synergize with AZD6244

We screened the LINCS kinase inhibitor-focused chemical library, which is made up of highly selective small molecule inhibitors, in an effort to find compounds that positively combine with the MEK inhibitor, AZD624424 against mutant NRAS-expressing cells (see schematic, Supplementary Figure 1). A number of interesting LINCS library compounds, including selective inhibitors of MEK and PI3K, were identified in the chemical screen as showing strong selective single agent activity against Ba/F3-NRAS G12D cells and the human mutant NRAS-expressing AML cell line, OCI-AML3, with little-to- no activity against parental Ba/F3 cells (known to be RAS independent for proliferation) (Supplementary Figure 2). AZD6244 was observed to synergize with LINCS library inhibitors of PI3K and mTOR, the targets of which mediate mutant RAS signaling, against mutant NRAS-expressing cells, Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D and OCI-AML3, but not wt RAS-expressing HEL cells (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 3). These results validate the suitability of the design of the chemical screen to identify inhibitors relevant to mutant RAS signaling as able to enhance the effects of AZD6244.

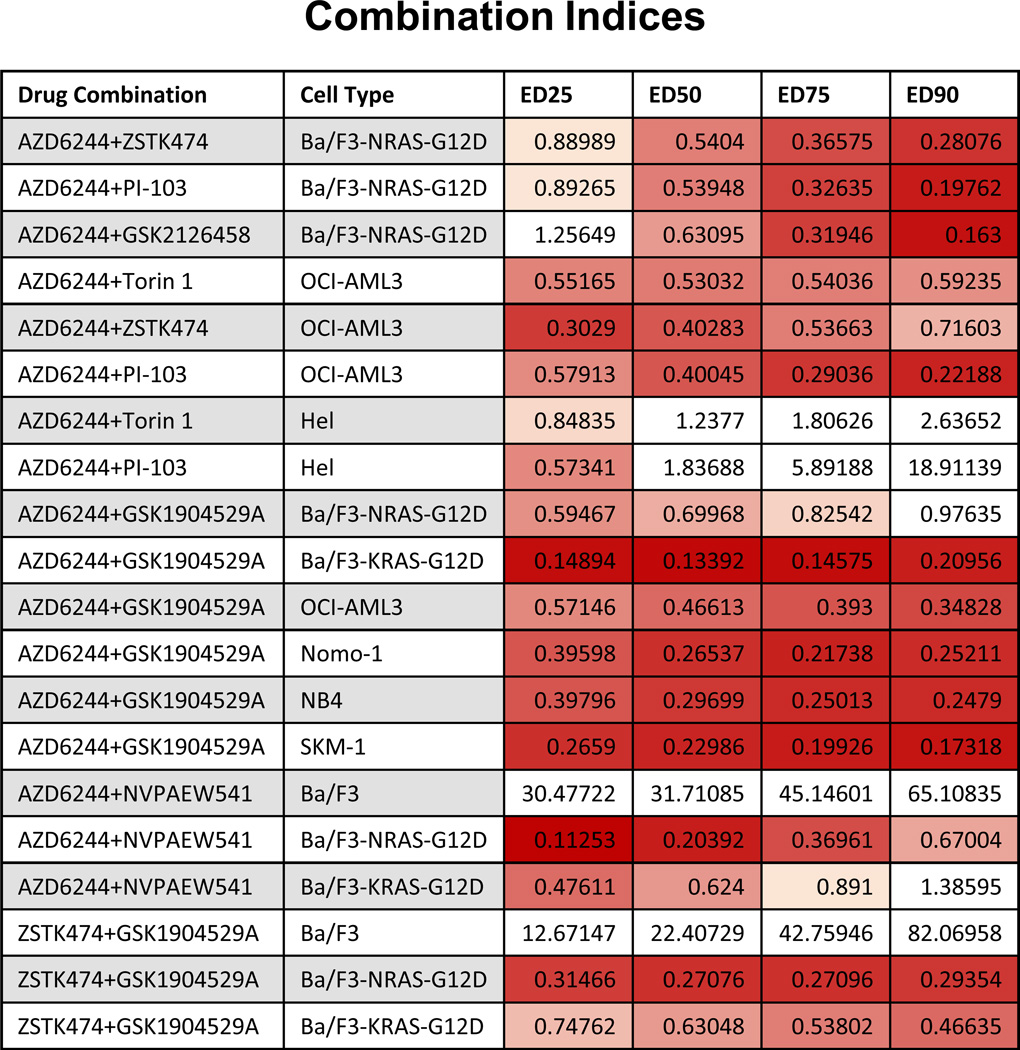

Figure 2. Combination indices corresponding to proliferation studies investigating effects of MEK inhibition combined with LINCS chemical library inhibitors against AML cell lines.

Values less than 0.9 indicate synergy and are in shades of red (darker shades mean higher synergy). Values greater than 0.9 do not indicate synergy and are colored white. Values less than one indicate synergy, whereas values greater than one indicate antagonism. Calcusyn combination indices can be interpreted as follows: CI <0.1 indicate very strong synergism; values 0.1–0.3 indicate strong synergism; values 0.3–0.7 indicate synergism; values 0.7–0.85 indicate moderate synergism; values 0.85–0.90 indicate slight synergism; values 0.9–1.1 indicate nearly additive effects; values 1.10–1.20 indicate slight antagonism; values 1.20–1.45 indicate moderate antagonism; values 1.45–3.3 indicate antagonism; values 3.3–10 indicate strong antagonism; values >10 indicate very strong antagonism. Note: For some experiments, namely those in which there was no observed single agent activity, combination indices could not be reliably calculated using the Calcusyn software.

The IGF-1R inhibitor, GSK1904529A, synergizes with AZD6244 against mutant RAS-expressing cells

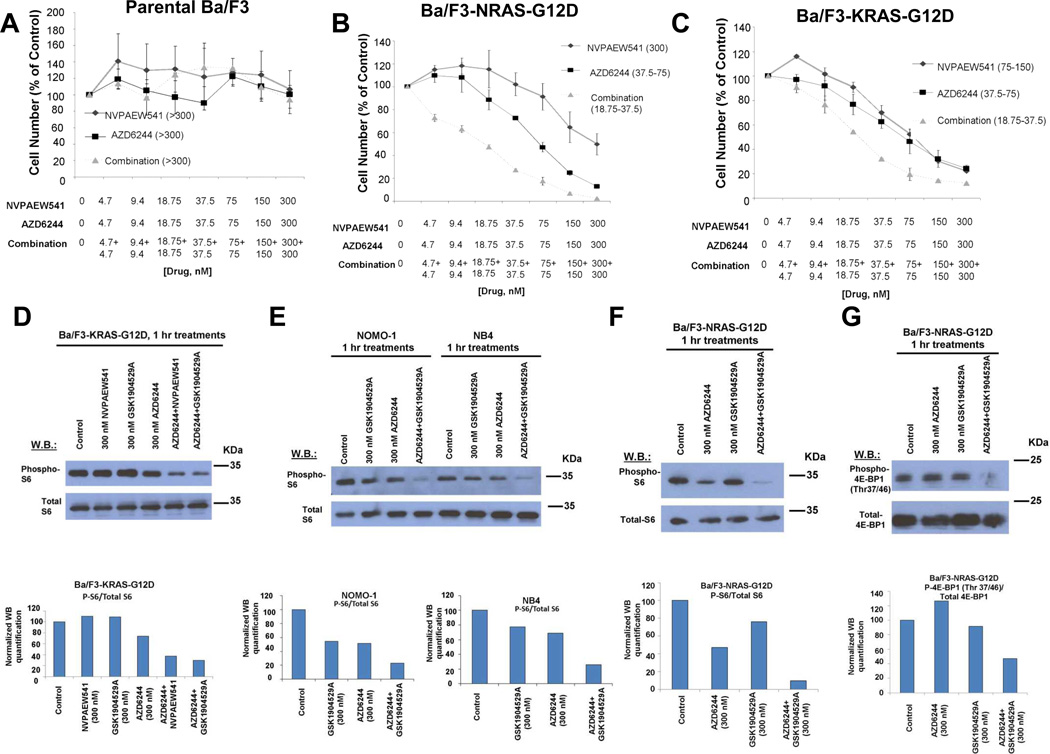

Interestingly, the chemical screen led to the identification of the IGF-1R inhibitor, GSK1904529A, as able to selectively potentiate the effects of AZD6244 against mutant NRAS- or KRAS-expressing Ba/F3 cells with no apparent combination effect observed against parental Ba/F3 cells (Figure 1A–C and Figure 2). This suggests that drug effects are targeted to mutant RAS, as exogenous expression of mutant RAS in growth factor-dependent Ba/F3 cells confers growth factor independence and renders cells solely dependent on mutant NRAS; selective inhibition of mutant RAS in this system would be expected to cause cells to die in the absence of growth factor. Target specificity of IGF-1R and MEK inhibition was further investigated by treating Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells with IGF-1R and MEK inhibitors, alone and combined, in the absence and presence of 15% WEHI-conditioned media (used as a source of IL-3) in parallel. As expected, potent suppression of Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D growth was observed following drug treatment in the absence of 15% WEHI, however partial IL-3 rescue was observed for each single agent and the potency of the combined inhibitors was substantially lower when Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells were cultured in the presence of 15% WEHI (Supplementary Figure 4). These results suggest that in the Ba/F3 system, IGF-1R inhibition and MEK inhibition selectively block RAS signaling without nonselectively interfering with IL-3-mediated signaling.

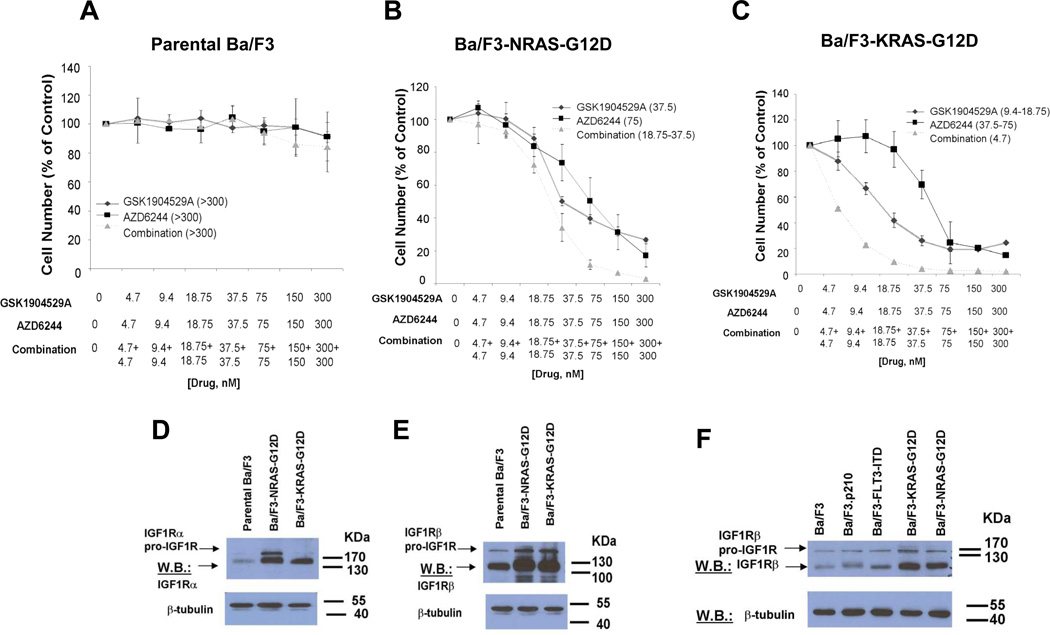

Figure 1. Identification of Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK) IGF1R inhibitor, GSK1904529A, as able to potentiate the effects of MEK inhibition in mutant NRAS- and-KRAS-expressing cells; characterization of IGF1R protein expression in mutant NRAS and KRAS-expressing cells.

(A–C) Approximately three-day proliferation studies performed with GSK1904529A and AZD6244 against Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells. AZD6244+GSK1904529A studies against Ba/F3 (n=3), Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D (n=6), and Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells (n=2). (D–E) IGF-1R expression in parental Ba/F3 versus Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D and Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells. (F) Comparison of IGF-1R expression in Ba/F3, Ba/F3.p210, Ba/F3-FLT3-ITD, and mutant RAS-expressing Ba/F3 cells. Shown in parentheses adjacent to figure legends are estimated IC50 values (nM) corresponding to individual drugs or drug combinations.

Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells were observed to over-express NRAS as compared to parental Ba/F3 cells, however neither single agent treatment nor drug combination treatment altered mutant RAS expression in mutant RAS-expressing Ba/F3 cells (Supplementary Figure 5A–B). Elevated levels of IGF-1R were also observed in Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D or Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells, as compared to parental Ba/F3 cells (Figure 1D–E). There was no effect of short-term (1 hour) treatment with AZD6244 or GSK1904529A, alone or combined, on levels of IGF-1R protein or activity in mutant RAS-expressing Ba/F3 cells (Supplementary Figure 5C–E). IGF-1R protein was observed to be phosphorylated in both parental Ba/F3 cells as well as Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells, with IGF-1R phosphorylation in parental Ba/F3 cells possibly associated with the IL-3- responsiveness of the cells (Supplementary Figure 5F). In a report by Soon and colleagues,25 IL-4 was shown to stimulate IGF-1R phosphorylation to a similar extent to IGF-1 in growth factor-dependent parental 32D cells. The link between IL-3 and IGF-1R activity is illustrated in a study in which IL-3 simulated IGF-1 in inducing cell cycle progression of IL-3-dependent FDC-PI cells made to conditionally proliferate in response to IGF-1R activation26. IGF-1R and downstream molecules characteristically transduce anti-apoptotic signals; IL-3 also induced anti-apoptotic pathways in these cells. It is possible, therefore, that we are observing a similar association between IL-3 and IGF-1R activity in parental Ba/F3 cells cultured in the presence of IL-3, as these cells are resistant to IGF-1R inhibitor and MEK inhibitor-induced apoptosis.

We observed IGF-1R levels in Ba/F3 cells transformed by FLT3-ITD or BCR-ABL to be similar to those observed in parental Ba/F3 cells, and considerably less than those observed in Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D and Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells (Figure 1F). These data suggest that not all oncogenes that are capable of conferring growth factor independence in Ba/F3 cells have the same inductive influence on IGF-1R, and support the notion that IGF-1R over-expression in mutant RAS-expressing Ba/F3 cells is associated with mutant RAS expression.

GSK1904529A and AZD6244 synergized against mutant NRAS-expressing cell lines OCI-AML3 and HL60, as well as active KRAS-expressing and dependent NOMO-1, NB4, and SKM-1 cells (Figure 2 and Figure 3A–E). In contrast, GSK1904529A and AZD6244 did not positively combine against wt RAS-expressing HEL or MOLM14 cells (Figure 3F–G), or normal mononuclear cells (Figure 3H). Importantly, increased apoptosis and cell cycle arrest and decreased soft agar colony formation were observed to correlate with combined drug treatment in mutant RAS-expressing AML cells, however not wt RAS-expressing AML cells (Supplementary Figure 6).

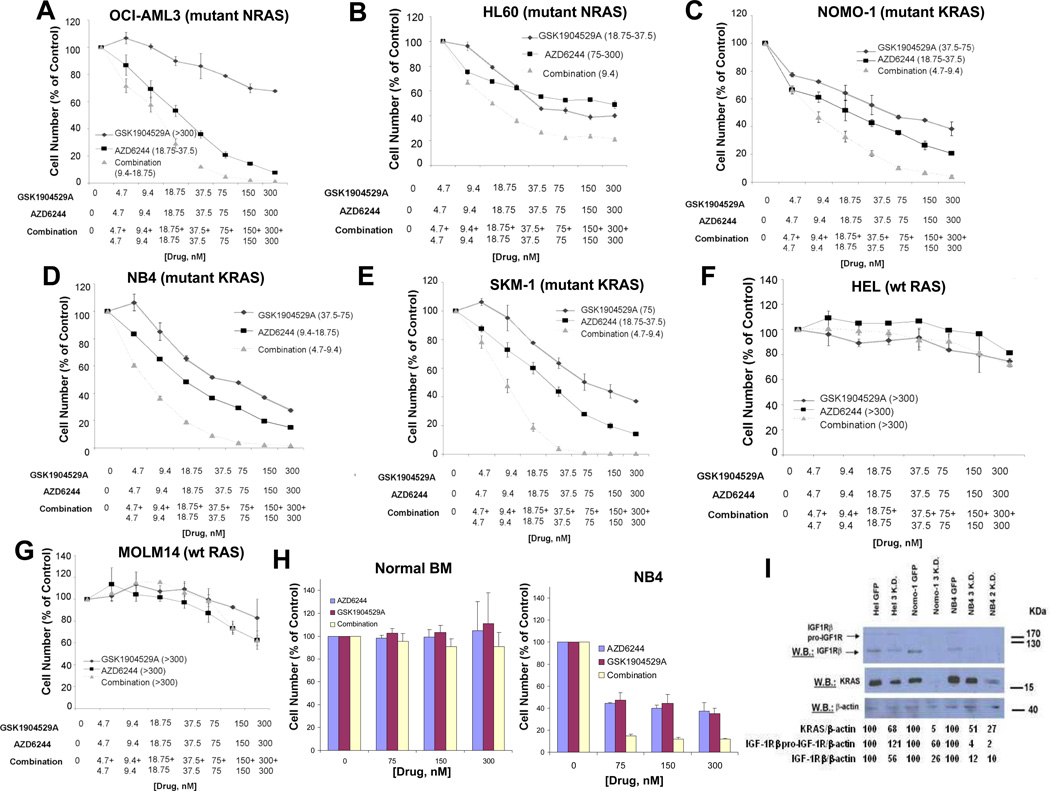

Figure 3. Combined effects of GSK1904529A and AZD6244 against human AML cells harboring wt or mutant RAS.

(A) Approximately 72-hr representative proliferation study performed with GSK1904529A and AZD6244, against mutant NRAS-expressing OCI-AML3 (n=3). (B) Approximately 48-hr proliferation study performed with GSK1904529A and AZD6244 against mutant NRAS-expressing HL60. (C–E) Approximately 72-hr representative proliferation studies performed with GSK1904529A and AZD6244 against NOMO-1 (KRAS G13D) (n=4), NB4 (KRAS A18D) (n=2), or SKM-1 (KRAS K117N) (n=2) cells. (F–G) Approximately 72-hr representative proliferation studies performed with GSK1904529A and AZD6244, against wt Ras-expressing Hel (n=2) and Molm14 cells. Shown in parentheses adjacent to figure legends for all graphs (A–G) are estimated IC50 values (nM) corresponding to individual drugs or drug combinations. (H) Shown as a normal control are the effects of two days of treatment using GSK1904529A and AZD6244, alone and combined, against mononuclear cells derived from normal donors cultured in DMEM+ 10% FBS (n=3). NB4 cells were tested in parallel as a positive control for drug stock integrity. (I) Effect of knockdown of KRAS on IGF1R expression in wt and mutant KRAS-expressing AML cells. Hairpins “2” and “3” were used for knockdown experiments.

As leukemic cells in patients are exposed to growth factors, especially in the bone marrow, which could lead to drug resistance, we tested the ability of IGF-1R inhibition and MEK inhibition to synergize against mutant RAS-positive AML cells in the presence of cytoprotective stromal-conditioned media (SCM) derived from two different human stromal cell lines (HS-5 and HS27a). Despite a 15–20% cytoprotective effect of SCM on drug-treated cells, synergy was observed between GSK1904529A and AZD6244 that was similar to that observed between the drugs in the absence of SCM (ie the ED50 for GSK1904529A and AZD6244 against NOMO-1 in the presence of HS27a SCM was 0.21917) (Supplementary Figure 7 and data not shown).

Of note, we observed a heightened response of mutant RAS-expressing HL60 cells to insulin growth factor (IGF), as compared to wt RAS-expressing HEL cells (Supplementary Figure 8). As some mutant RAS-positive cells may respond to IGF existing in serum, these results suggest that an IGF-1R inhibitor may be more effective than an AKT inhibitor in suppression of PI3K/AKT signaling in mutant RAS-expressing cells. The data also support the use of HEL cells as a wt RAS-expressing control in studies involving IGF-1R inhibition.

Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells treated overnight with a MEK inhibitor (AZD6244, 300 nM) or PI3K inhibitors (BEZ-235 (1000 nM), PI-103 (1000 nM) showed a small reduction in IGF-1R proreceptor and IGF-1Rβ levels (data not shown). However, KRAS KD selectively led to substantial decreases in IGF-1R levels in active KRAS-expressing cell lines, NOMO-1 and NB4 (Figure 3I). The KD studies revealed these cell lines, as well as the active KRAS-expressing line, SKM-1, to be dependent on KRAS as KRAS KD resulted in a loss of cell viability (data not shown). This is in contrast to wt RAS-expressing HEL cells, for which KRAS KD did not lead to a loss of cell viability (data not shown).

GSK1904529A synergizes with PI3K inhibitor, ZSTK474, against mutant RAS-expressing cells

To determine whether the positive combination observed between GSK1904529A and AZD6244 is unique or can be replicated by combining GSK1904529A with inhibitors of other downstream mediators of RAS transformation, we investigated the ability of GSK1904529A to positively combine with an inhibitor of PI3K signaling. The combination of GSK1904529A and the PI3K inhibitor, ZSTK47427, was antagonistic against parental Ba/F3 cells. However, a positive drug combination effect was observed against mutant NRAS- and mutant KRAS-expressing Ba/F3 cells (Supplementary Figure 9).

Inhibition of Erk1/Erk2 phosphorylation predicts responsiveness to GSK1904529A and AZD6244 in RAS-transformed cells

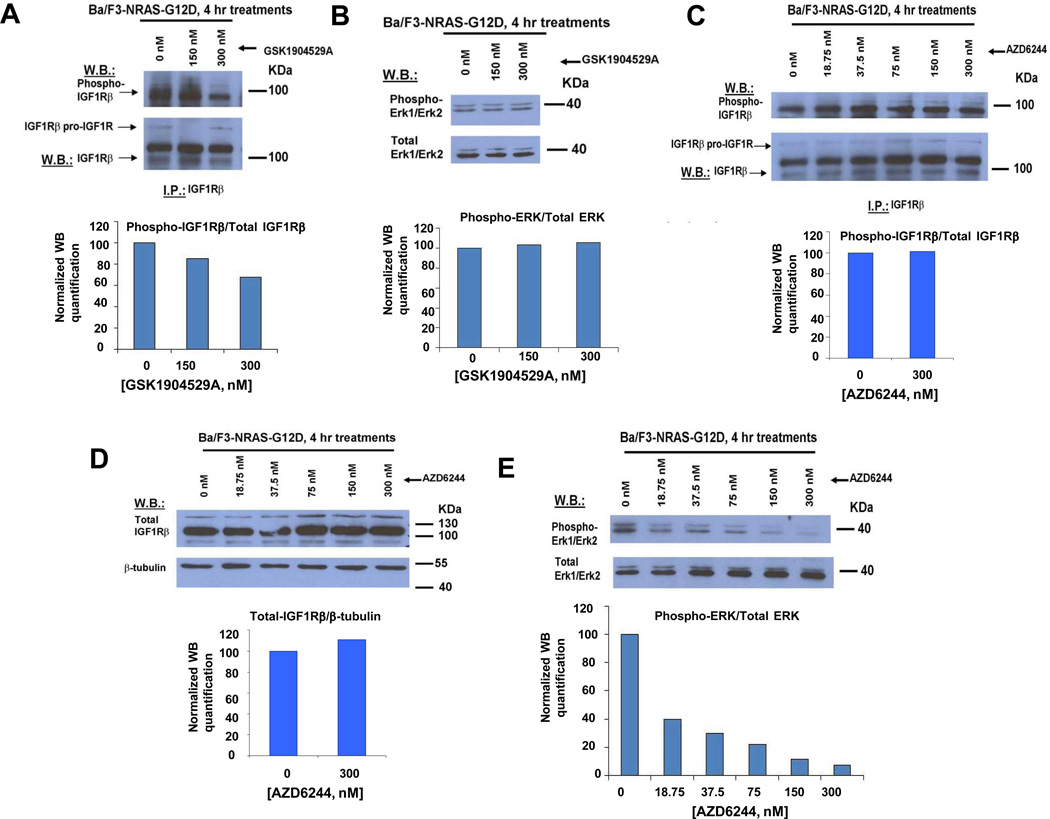

In an attempt to better understand the mechanism underlying the observed synergy between AZD6244 and GSK1904529A against RAS-transformed cells, we tested the single agent effects of AZD6244 and GSK1904529A on both Erk1/Erk2 and IGF-1R expression/activity. GSK1904529A was observed to inhibit phosphorylation of IGF-1R in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4A), however showed no inhibitory activity against phosphorylation of Erk1/Erk2 (Figure 4B). Similarly, AZD6244 did not inhibit the activity or expression of IGF-1R (Figure 4C–D), however inhibited phosphorylation of Erk1/Erk2 in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4E). These data suggest that GSK1904529A and AZD6244 are selective toward their respective molecular targets; the lack of target redundancy is supportive of the observed synergy between the two agents in this system.

Figure 4. Effects of GSK1904529A and AZD6244 as single agents, respectively, on mediators of IGF-1R- and ERK1/ERK2-signaling pathways.

(A–B) Effect of GSK1904529A on phosphorylation of IGF-1R (A) and Erk1/Erk2 (B). (C–E) Effect of AZD6244 on phosphorylation of IGF-1R (C), IGF-1R protein expression levels (D), and phosphorylation of Erk1/Erk2 (E).

We investigated whether or not a correlation exists between the heightened responsiveness of mutant RAS-expressing cells to simultaneous IGF-1R and MEK inhibition and the basal expression/activity of integral mediators of the IGF-1R or Raf/MEK/ERK signaling pathways. Higher basal levels of phospho-Erk1/Erk2 were observed in Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D and Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells, as compared to parental Ba/F3 cells (Supplementary Figure 10A). Generally, high levels of phosphorylated Erk/Erk2 were observed in wt and mutant RAS-expressing human AML lines (Supplementary Figure 10B). IGF-1R was observed to be detectable (expressed) and phosphorylated (active) in wt and mutant RAS-expressing AML lines (Supplementary Figure 10C–D), however mutant NRAS-expressing OCI-AML3 and mutant KRAS-expressing SKM-1 showed comparatively elevated phospho/total IGF-1R ratios in the panel of AML lines studied (Supplementary Figure 10C).

We observed significant inhibition of ERK phosphorylation by AZD6244 in mutant NRAS- and mutant KRAS-expressing cells, which was sustained in cells treated with both GSK1904529A and AZD6244 (Supplementary Figure 11 and data not shown). When compared to MOLM14 and HEL cells, OCI-AML3 cells treated with the same concentrations of AZD6244 and GSK1904529A showed substantially higher phospho-ERK inhibition by AZD6244 or the drug combination (Supplementary Figure 11A). The effects of AZD6244, alone or combined with GSK1904529A, were similarly more strongly suppressive of ERK phosphorylation in mutant KRAS-expressing cells as compared to wt RAS-expressing HEL cells (Supplementary Figure 11B). These results suggest that the inhibition of phospho-Erk1/Erk2 is likely required for a MEK inhibitor and IGF-1R inhibitor to positively combine against mutant RAS-expressing or wt RAS-dependent AML cells.

The selective IGF-1R inhibitor, NVP-AEW541, synergizes with AZD6244 against mutant RAS-expressing cells

As GSK1904529A is equipotent toward the insulin receptor (IR) and IGF-1R receptor, and NVP-AEW541 (Novartis Pharma AG) shows far greater (100-fold) selectivity toward IGF-1R over IR, we were interested in testing the ability of the more selective IGF-1R inhibitor to synergize with AZD6244 against mutant RAS-expressing cells. Whereas the combination of NVP-AEW541 and AZD6244 against parental Ba/F3 cells was antagonistic, this combination showed synergy against Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D and Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells (Figure 2 and Figure 5A–C and Supplementary Figure 4). NVP-AEW541, similar to GSK1904529A, inhibited the phosphorylation of IGF-1R in a concentration-dependent manner, however did not inhibit phosphorylation of Erk1/Erk2 (Supplementary Figure 12).

Figure 5. Combined effects of Novartis IGF-1R inhibitor, NVPAEW541, and AZD6244 on mutant RAS-expressing cells; identification of S6 and 4E-BP1 as potential mediators of synergy between inhibitors of IGF-1R and MEK in mutant RAS-expressing cells.

(A–C) Approximately 72-hr proliferation studies performed with NVPAEW541 and AZD6244, alone or combined, against parental Ba/F3 and Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D or Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells. Shown in parentheses adjacent to figure legends are estimated IC50 values (nM) corresponding to individual drugs or drug combinations. (D) Effects of IGF1R inhibition or MEK inhibition, alone or combined, on phospho-S6 expression in Ba/F3-KRAS-G12D cells. (E) Effects of IGF-1R inhibition or MEK inhibition, alone or combined, on phospho-S6 expression in active KRAS-expressing human AML lines, Nomo-1 and NB4. (F) Effects of IGF-1R inhibition, alone or combined, on phospho-S6 expression in Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells. (G) Effects of IGF-1R inhibition, alone or combined, on phospho-4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) in Ba/F3-NRAS-G12D cells.

Ribosomal protein S6 and 4E-BP1 as mediators of synergy between IGF-1R inhibition and MEK inhibition in mutant RAS-expressing cells

We did not observe enhanced inhibition of Erk1/Erk2 or AKT phosphorylation in mutant RAS-expressing cells treated with the combination of MEK and IGF-1R inhibitors, as compared to either agent alone (Supplementary Figure 13). Inhibition of phosphorylation of AKT, however, is clearly shown by both IGF-1R inhibitors, NVPAEW541 and GSK1904529A, which is expected as AKT is downstream of IGF-1R. The lack of enhanced inhibition of phospho-AKT by the drug combination is also not surprising, as AZD6244 selectively acts on the MAPK signaling pathway. The lack of elevated inhibition of phosphorylation of Erk1/Erk2 suggests that this factor may not contribute significantly to the observed synergy between IGF-1R and MEK inhibition.

As these results are consistent with each inhibitor selectively targeting its own independent signaling pathway, we decided to investigate drug combination effects on signaling mediators downstream of IGF-1R and RAS that are influenced by both the PI3K//PTEN/AKT/mTOR and Raf/MEK/ERK signaling. We identified ribosomal protein S6 and 4E-BP1 as potential mediators of IGF-1R and MEK inhibitor synergy, with the phosphorylation of ribosomal protein S6 and 4E-BP1 at Thr37/46 more greatly suppressed by the combination of IGF-1R and MEK inhibition in mutant RAS-transformed cells (Figure 5D–G). In contrast, we observed no enhanced inhibition of phosphorylation of 4E-BP1 at Serine 65 by the drug combination (Supplementary Figure 14), suggesting that this phosphorylation site may not significantly contribute to the observed synergy between IGF-1R and MEK inhibition. The enhanced suppression of S6 and 4E-BP1 (Thr 37/46) phosphorylation may thus add to the individual or parallel effects of both inhibitors in mediating growth inhibition.

Effects of IGF-1R KD in mutant RAS-expressing cells

KD of IGF-1R in the mutant KRAS-expressing cell line, NB4, led to a decrease in cell growth (Supplementary Figure 15A, E), suggesting that IGF-1R is important for the viability of these cells. Single agent and drug combination effects were modestly augmented in IGF-1R KD cells as compared to control cells (Supplementary Figure 15B). In contrast, IGF-1R KD in wt RAS-expressing HEL cells had less of an inhibitory effect on cell growth and did not affect drug sensitivity of the cells (Supplementary Figure 15C–D, F). Interestingly, there was no apparent decrease in the phosphorylation of AKT or downstream signaling mediators, 4E-BP1 or S6, in IGF-1R KD cells (data not shown). One possibility for this is that the more transient timing of inhibition of IGF-1R and MEK through pharmacological inhibition (2–3 days) as compared to that of IGF-1R gene knock down (over a week) may make the latter more subject to compensatory feedback loops characteristic of IGF-1R signaling.

In vivo efficacy of IGF-1R inhibition and MEK inhibition in a mutant NRAS-positive leukemia mouse model

We utilized a mouse model of mutant NRAS-positive leukemia to examine the in vivo effects of IGF-1R inhibition combined with MEK inhibition. The combination of NVP-AEW541 and AZD6244 was observed to be significantly more effective in suppressing leukemia burden in mice tail vein-injected with OCI-AML3-luc+ cells, as compared with either agent alone following one week of drug administration (Figure 6) and mouse spleen sizes, measured one week later, were observed to be smallest in drug combination-treated mice (Supplementary Figure 16). It should be noted, however, that while a difference in engraftment was observed on day 7 following drug treatment between single agent- treated and combination-treated mice, there was continued growth of leukemic cells in drug-treated groups.

Figure 6. Combined effects of IGF-1R and MEK inhibition in an in vivo model of mutant NRAS-positive leukemia.

In vivo effects of NVP-AEW541 and AZD6244, alone and combined, in a xenograft model of mutant NRAS-positive AML. Representative mouse images are shown comparing baseline images prior to drug treatment and following 7 days of treatment with NVP-AEW541 (50 mg/kg once per day), AZD6244 (25 mg/kg once per day), or a combination of the two agents. Corresponding bioluminescence values for NVP-AEW541-treated mice (n=3), AZD6244-treated mice (n=4), and combination-treated mice (n=4) are shown as a bar graph. P values indicating statistical significance are shown and were derived by Student's t test. Significance was defined as p<0.05.

Efficacy of IGF-1R inhibition and MEK inhibition against mutant NRAS-positive primary AML cells

We also tested the combined IGF-1R and MEK inhibition in three mutant NRAS-expressing primary AML patient cells, using the same drug concentrations used for cell line-based studies (0, 75, 150, 300 nM), and observed more cell death with the combination than either agent alone (Supplementary Figure 17). Importantly, for patient sample AML3 (NRAS-G13V, with 92% bone marrow blasts), combination indices suggested nearly additive-synergistic effects for the combination of NVP-AEW541 and AZD6244: ED25 (0.98304, nearly additive); ED50 (0.21557, synergy); ED75 (0.14790, synergy); ED90 (0.26906, synergy). These data support the potential clinical utility of this drug combination for mutant NRAS-positive AML.

Discussion

In hematologic malignancies, NRAS and KRAS are each frequently mutated. In AML, NRAS codon 12, 13, or 61 mutations have been reported in 10–11% of cases, whereas KRAS mutations have been reported in 5% of cases28–29. Direct inhibition of mutant RAS with small molecules has proven difficult and the effects of targeting downstream RAS effectors has been difficult to predict. This justifies targeting multiple downstream effectors of RAS or RAS-associated factors as a strategy designed to increase clinical efficacy and circumvent drug resistance in mutant RAS-positive malignancies.

As there is a high degree of uncertainty with respect to the exact contribution of RAS effectors to growth and survival of leukemia, screening of targeted small molecule inhibitors can yield significant mechanistic and clinical insights. Seeing that only limited efficacy has been achieved with targeting downstream effectors of mutant RAS, such as MEK, we used a chemical screen approach, employing the LINCS chemical library comprised of highly selective kinase inhibitors, to identify agents able to effectively enhance MEK inhibition in mutant NRAS-expressing cells. LINCS library compounds were anticipated to be useful, because of their limited spectrum of kinase targets, to more easily identify kinase mediators of RAS signaling that could be exploited for the purpose of drug development. Consistent with what has been reported in the literature, we identified through this screen several inhibitors of mTOR and PI3K/AKT signaling, which function downstream of RAS, as able to potentiate the effects of the MEK inhibitor, AZD6244.

Importantly, however, we also identified the IGF-1R/IR inhibitor, GSK1904529A, as able to potentiate the effects of AZD6244 against mutant RAS-expressing AML cells. While it has been proposed that dual inhibition of IGF-1R and IR may result in greater therapeutic efficacy and overriding resistance to anti-IGF-1R therapies30–32, this dual inhibition may also lead to clinical limitations resulting from adverse effects/off-target toxicity. Importantly, potentiation of AZD6244 by an IGF-1R inhibitor, NVP-AEW541, which shows 100-fold higher selectivity for IGF-1R over IR, was also observed in our studies. This suggests that synergy with a MEK inhibitor can be achieved with either an IGF-1R/IR inhibitor or a more targeted IGF-1R inhibitor.

Potential clinical relevance of our findings is supported by the high degree of clinical investigation currently underway, namely the preclinical or clinical development of approximately thirty IGF-1R-targeting agents and the close to sixty clinical trials evaluating such agents alone or in combination with other inhibitors (reviewed in33). The two primary approaches to inhibiting IGF-1R are through small molecule inhibition or antibodies, and at the present time it is unclear which is likely to be more effective in patients (reviewed in33). While early clinical studies support the notion of IGF-1R as being a viable therapeutic target for certain cancers, variability in patient responsiveness and toxicity associated with certain drug combinations warrant identification of predictive biomarkers to identify probable clinical responders, and highlight a need for rational development of novel drug combination strategies focused on IGF-1R-mediated signaling inhibition in combination with other targeted therapies. In response, we have identified mutant RAS-expressing leukemia as a promising disease target for therapy dependent on IGF-1R inhibition coupled with targeted inhibition of mutant RAS signaling.

Several studies have implicated a functional association between RAS transformation and IGF-1R. In an inducible NRAS (Q61K)-driven genetically engineered mouse model of melanoma, four days of genetic extinction of NRAS (Q61K) expression led to a substantial down-regulation of IGF-1Rβ expression, according to reverse phase protein array profiling34. In addition, mouse embryo fibroblasts devoid of IGF-1R cannot be transformed by Ha-RAS35–36. In addition to demonstrating synergy between selective IGF-1R inhibition and targeted inhibition of downstream RAS signaling pathways, we present here the novel positive correlation between mutant RAS expression and IGF-1R protein expression in mutant RAS-transformed hematopoietic cells. It is possible that the increased IGF-1R levels observed in mutant RAS-expressing cells may be a hallmark prosurvival characteristic of RAS transformation that enables cells to thrive and disease to progress.

The combination of IGF-1R inhibitors with inhibitors of RAS signaling, including BRAF or MEK, has been suggested for breast cancer in response to reports of MEK inhibitor-induction of PI3K pathway signaling37–38, as well as KRAS mutant colorectal cancer39 and lung cancer40–41. Similarly, the combination of IGF-1R inhibitors with inhibitors of AKT or mTOR has been proposed for solid tumors, including breast and prostate cancer, as a strategy to override drug resistance due to negative feedback loops associated with mTOR inhibition42.

Previous reports have implicated IGF-1R as a potentially important target in AML due to high IGF-1R expression30,43–44 and enhancement of AML cell survival and proliferation by IGF-1R signaling45. Of relevance, targeted small molecule inhibition of IGF-1R, such as by NVP-AEW541 or NVP-ADW742, or dual inhibition of IGF-1R/IR receptor, such as by BMS-536924, leads to induction of apoptosis in AML cells30,42,45–46. mTOR inhibition causes induction of PI3K/AKT signaling through increased IGF-1R signaling, and combined mTOR and PI3K/AKT inhibition leads to additive antiproliferative effects in AML47. Further, antibody targeting of IGF-1R in combination with inhibitors of Raf/MEK/ERK or PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling has been shown to be synergistic against hematopoietic cells engineered to express IGF-1R48.

Our findings are consistent with these studies and demonstrate a correlation between mutant RAS protein expression and IGF-1R protein expression in mutant RAS-expressing AML. The present study is also the first to highlight- in mutant RAS-positive AML- the potential therapeutic benefit of dual suppression of IGF-1R and RAS signaling. This novel combination strategy warrants further investigation as a therapeutic approach that could bypass some mechanisms of drug resistance associated with MEK inhibition and that therefore may be of potential clinical benefit in mutant RAS-driven leukemia.

Supplementary Material

Statement of Translational Relevance.

Use of a multi-targeted therapy approach for malignancies driven by the highly prevalent RAS oncogene is warranted in light of the elusiveness of direct RAS inhibition and limited clinical efficacy associated with targeted inhibition of key mediators of RAS signaling. A novel chemical screen utilizing highly targeted agents to more easily identify kinases important for RAS signaling led to the discovery of synergism between MEK inhibition and inhibition of the insulin growth factor 1 receptor (IGF-1R) against mutant RAS-positive leukemia. Elevation of functional IGF-1R expression in mutant RAS-expressing leukemia cells further supports the role of this molecule as a viable target and highlights the potential for therapeutic intervention. A combinatorial chemical screen that seeks to identify molecules that synergize with the inhibition of bona fide RAS effectors may yield drugs with therapeutic potential and help to understand mechanisms of RAS transformation.

Acknowledgments

N.S. Gray is supported by NIH LINCS grant HG006097. J.D.G. receives research support and has a financial interest with Novartis Pharma AG.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None of the authors included in this manuscript have a financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ward AF, Braun BS, Shannon KM. Targeting oncogenic RAS signaling in hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2012;120:3397–3406. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-378596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tyner JW, Erickson H, Deininger MWV, Willis SG, Eide CA, Levine RL, et al. High-throughput sequencing screen reveals novel, transforming RAS mutations in myeloid leukemia patients. Blood. 2009;113:1749–1755. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-152157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.MacKenzie KL, Dobnikov A, Millington M, Shounan Y, Symonds G. Mutant N-ras induces myeloproliferative disorders and apoptosis in bone marrow repopulated mice. Blood. 1999;93:2043–2056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parikh C, Subrabmanyam R, Ren R. Oncogenic NRAS rapidly and efficiently induces CMML- and AML-like diseases in mice. Blood. 2006;108:2349–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-08-009498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh C, Subrahmanyam R, Ren R. Oncogenic NRAS, KRAS, and HRAS exhibit different leukemogenic potentials in mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:7139–7146. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baines AT, Xu D, Der CJ. Inhibition of RAS for cancer treatment: the search continues. Future Med Chem. 2011;3:1787–1808. doi: 10.4155/fmc.11.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostrem JM, Peters U, Sos ML, Wells JA, Shokat KM. K-RAS (G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013;503:548–551. doi: 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim SM, Westover KD, Ficarro SB, Harrison RA, Choi HG, Pacold ME, et al. Therapeutic targeting of oncogenic K-RAS by a covalent catalytic site inhibitor. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:199–204. doi: 10.1002/anie.201307387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karp JE, Lancet JE, Kaufmann SH, End DW, Wright JJ, Bol K, et al. Clinical and biologic activity of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 in adults with refractory and relapsed acute leukemias: a phase I clinical-laboratory correlative trial. Blood. 2001;97:3361–3369. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downward J. Targeting RAS signaling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lauchle JO, Kim D, Le DT, Akagi K, Crone M, Krisman K, et al. Response and resistance to MEK inhibition in leukemias initiated by hyperactive RAS. Nature. 2009;461:411–414. doi: 10.1038/nature08279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solit DB, Garraway LA, Pratilas CA, Sawai A, Getz G, Basso A, et al. BRAF mutation predicts sensitivity to MEK inhibition. Nature. 2006;439:358–362. doi: 10.1038/nature04304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeh TC, Marsh V, Bernat BA, Ballard J, Colwell H, Evans RJ, et al. Biological characterization of ARRY-142886 (AZD6244), a potent, highly selective mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase ½ inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1576–1583. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jain N, Curran E, Lyengar NM, Diaz-Flores E, Kunnavakkam R, Popplewell L, et al. Phase II study of the oral MEK inhibitor Selumetinib in advanced acute myelogenous leukemia: a University of Chicago Phase II Consortium Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:490–498. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sabbatini P, Rowand JL, Groy A, Korenchuk S, Liu Q, Atkins C, et al. Antitumor activity of GSK1904529A, a small-molecule inhibitor of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor tyrosine kinase. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3058–3067. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuo Y, MacLeod RA, Uphoff CC, Drexler HG, Nishizaki C, Katayama Y, et al. Two acute monocytic leukemia (AML-M5a) cell lines (MOLM13 and MOLM14) with interclonal phenotypic heterogeneity showing MLL-AF9 fusion resulting from an occult chromosome insertion, ins(11;9)(q23;p22p23) Leukemia. 1997;11:1469–1477. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimbrel EA, Davis TN, Bradner JE, Kung AL. In vivo pharmacodynamic imaging of proteosome inhibition. Mol Imaging. 2009;8:140–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelly LM, Liu Q, Kutok JL, Williams IR, Boulton CL, Gilliland DG. FLT3 internal tandem duplication mutations associated with human acute myeloid leukemias induce myeloproliferative disease in a murine bone marrow transplant model. Blood. 2002;99:310–318. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daley GQ, Baltimore D. Transformation of an interleukin 3-dependent hematopoietic cell line by the chronic myeloid leukemia-specific p210 BCR-ABL protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:9312–9316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.23.9312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okuda K, Golub TR, Gilliland DG, Griffin JD. p210BCR-ABL, p190BCR-ABL, and TEL/ABL activate similar signal transduction pathways in hematopoietic cell lines. Oncogene. 1996;13:1147–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sattler M, Salgia R, Okuda K, Uemura N, Durstin MA, Pisick E, et al. The proto-oncogene product p120CBL and the adaptor proteins CRKL and c-CRK link c-ABL, p190BCR-ABL and p210BCR-ABL to the phosphatidylinositol-3' kinase pathway. Oncogene. 1996;12:839–846. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, Bruggen J, Cown-Jacob SW, Ray A, et al. Characterization of AMN107, a selective inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:129–141. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chou TC, Talalay P. Quantitative analysis of dose-effect relationships: the combined effects of multiple drugs or enzyme inhibitors. Adv Enzyme Regul. 1984;22:27–55. doi: 10.1016/0065-2571(84)90007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davies BD, Logie A, McKay JS, Martin P, Steele S, Jenkins R, et al. AZD6244 (ARRY 142886) a potent inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-related kinase kinase 1 /2 kinases: mechanism of action in vivo, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship and potential for combination in preclinical models. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2209–2219. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soon L, Flechner L, Gutkind JS, Wang L-H, Baserga R, Pierce JH. Insulin-like growth factor 1 synergizes with interleukin 4 for hematopoietic cell proliferation independent of insulin receptor substrate expression. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3816–3828. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shelton JG, Steelman LS, White ER, McCubrey JA. Synergy between PI3K/Akt and Raf/MEK/ERK pathways in IGF-1R mediated cell cycle progression and prevention of apoptosis in hematopoietic cells. Cell Cycle. 2004;3:372–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yaguchi S, Fukui Y, Koshimizu I, Yoshimi H, Matsuno T, Gouda H, et al. Antitumor activity of ZSTK474, a new phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:545–556. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowen DT, Frew ME, Hills R, Gale RE, Wheatley K, Groves MJ, et al. RAS mutation in acute myeloid leukemia is associated with distinct cytogenetic subgroups but does not influence outcome in patients younger than 60 years. Blood. 2005;106:2113–2119. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bacher U, Hafterlach T, Schoch C, Kern W, Schnittger S. Implications of NRAS mutations in AML: a study of 2502 patients. Blood. 2006;107:3847–3853. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wahner Hendrickson AE, Haluska P, Schneider PA, Loegering DA, Peterson KL, Attar R, et al. Expression of insulin receptor isoform A and insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in human acute myelogenous leukemia: effect of the dual-receptor inhibitor BMS-536924 in vitro. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7635–7643. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chapuis N, Lacombe C, Tamburini J, Bouscary D, Mayeux P. Insulin receptor A and IGF-1R in AML- Letter. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7010. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ulanet DB, Ludwig DL, Kahn CR, Hanahan D. Insulin receptor functionally enhances multistage tumor progression and conveys intrinsic resistance to IGF-1R targeted therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10791–10798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914076107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zha J and Lackner MR. Targeting the insulin-like growth factor receptor-1R pathway for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2512–2517. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kwong LN, Costello JC, Liu H, Jiang S, Helms TL, Langsdorf AE, et al. Oncogenic NRAS signaling differentially regulates survival and proliferation in melanoma. Nat Med. 2012;18:1503–1510. doi: 10.1038/nm.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gatzka M, Prisco M, Baserga R. Stabilization of the RAS oncoprotein by the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor during anchorage-independent growth. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4222–4230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang TY, Tsai WJ, Chou CK, Chow NH, Leu TH, Liu HS. Identifying the factors and signal pathways necessary for anchorage-independent growth of Ha-ras oncogene-transformed NIH/3T3 cells. Life Sci. 2003;73:1265–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00428-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoeflich KP, O’Brien C, Boyd Z, Cavet G, Guerrero S, Jung K, et al. In vivo antitumor activity of MEK and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitors in basal-like breast cancer models. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4649–4664. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mirzoeva OK, Das D, Heiser LM, Bhattacharya S, Siwak D, Gendelman R, et al. Basal subtype and MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK)-phosphoinositide 3-kinase feedback signaling determine susceptibility of breast cancer cells to MEK inhibition. Cancer Res. 2009;69:565–572. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ebi H, Corcoran RB, Singh A, Chen Z, Song Y, Lifshits E, et al. Receptor tyrosine kinases exert dominant control over PI3K signaling in human KRAS mutant colorectal cancers. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4311–4321. doi: 10.1172/JCI57909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Engelman JA, Chen L, Tan X, Crosby K, Guimaraes AR, Upadhyay R, et al. Effective use of PI3K and MEK inhibitors to treat mutant KRAS G12D and PIK3CA H1047 murine lung cancers. Nat Med. 2008;14:1351–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molina-Arcas M, Hancock DC, Sheridan C, Kumar MS, Downward J. Coordinate direct input of both KRAS and IGF1 receptor to activation of PI3 kinase in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Discovery. 2013;3:548–563. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-12-0446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O’Reilly KE, Rojo F, She QB, Solit D, Mills GB, Smith D, et al. mTOR inhibition induces upstream receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and activates AKT. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1500–1508. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.He Y, Zhang J, Zheng J, Du W, Xiao H, Liu W, et al. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor kinase inhibitor, NVP-AD2742, suppresses survival and resistance to chemotherapy in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Oncol Res. 2010;19:35–43. doi: 10.3727/096504010x12828372551821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qi H, Xiao L, Lingyun W, Ying T, Yi-Zhi L, Shao-Xu Y, et al. Expression of type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor in marrow nucleated cells in malignant hematological disorders: correlation with apoptosis. Ann Hematol. 2006;85:95–101. doi: 10.1007/s00277-005-0031-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Doepfner KT, Spertini O, Arcaro A. Autocrine insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling promotes growth and survival of human acute myeloid leukemia cells via the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Leukemia. 2007;21:1921–1930. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tazzari PL, Tabellini G, Bortul R, Papa V, Evangelisti C, Grafone T, et al. The insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor kinase inhibitor NVP-AEW541 induces apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia cells exhibiting autocrine insulin-like growth factor-1 secretion. Leukemia. 2007;21:886–896. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tamburini J, Chapuis N, Bardet V, Park S, Sujobert P, Willems L, et al. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibition activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/AKT by up-regulating insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor signaling in acute myeloid leukemia: rationale for therapeutic inhibition of both pathways. Blood. 2008;111:379–382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-080796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bertrand FE, Steelman LS, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Shelton JG, White ER, et al. Synergy between an IGF-1R antibody and Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway inhibitors in suppressing IGF-1R-mediated growth in hematopoietic cells. Leukemia. 2006;20:1254–1260. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.