Abstract

Both diabetes and cancer are prevalent diseases whose incidence rates are increasing worldwide, especially in countries that are undergoing rapid industrialization changes. Apparently, lifestyle risk factors including diet, physical inactivity and obesity play pivotal, yet preventable, roles in the etiology of both diseases. Epidemiological studies provide strong evidence that subjects with diabetes are at significantly higher risk of developing many forms of cancer and especially solid tumors. In addition to pancreatic and breast cancer, the incidence of colorectal cancer and prostate cancer is increased in type 2 diabetes. While diabetes (type 2) and cancer share many risk factors, the biological links between the two diseases are poorly characterized. In this review, we highlight the mechanistic pathways that link diabetes to colorectal and prostate cancer and the use of Metformin, a diabetes drug, to prevent and/or treat colorectal and prostate cancer. We review the role of AMPK activation in autophagy, oxidative stress, inflammation, apoptosis, and cell cycle progression.

Keywords: Diabetes, Colorectal Cancer, Prostate Cancer, Metformin, AMPK, mTOR

1. Introduction

The current worldwide diabetic epidemic is not only influencing the morbidity and mortality of the present generation, but with no doubt has a trans-generational epigenetic inheritance impact with increasing prevalence for cancer with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM) 1-3. The raised risk of cancer in T2DM 4-7, and with a demographic shift in age towards the over 65 years old, translates into considerable financial and social burden on finite health care budgets. The link between T2DM and raised incidence of colorectal cancer (CRC) and prostate cancer (PC), and mortality, has been related to a constellation of risk factors pertaining to metabolic syndromes, specifically insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hyperglycemia 8-11. A significant point to note here is that excessive plasma concentration of insulin and glucose correlate with accelerated aging 12. Hence, there is an urgent need for targeted therapy for comorbid diabetes and cancer. One such medication is the old workhorse for T2DM, metformin, which has generated considerable attention. Therefore, our review primarily focuses on metformin use in diabetics with either colorectal or prostate cancers. The properties and biological mechanisms of metformin are further discussed in relation to diabetes and cancer, followed by its applications in in vitro, in vivo and clinical studies.

2. Biological actions, pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenetics of metformin

The history of metformin, a biguanide derivative, dates back to the Middle-Ages, and its structural analogue galegine was isolated from Galega officinalis (goat's rue, French lilac, Italian fitch); a plant native to the Middle East that has been used for treatment of diabetes in Europe 13. Accumulating evidence shows beneficial survival effects of therapeutic intervention with metformin for cancer patients with T2DM (Fig. 1). Metformin, a cationic (hydrophilic base) drug, exerts its pleiotropic pharmacological effects beyond those of metabolic control 14, and includes favorable anti-inflammatory outcomes 15, 16.

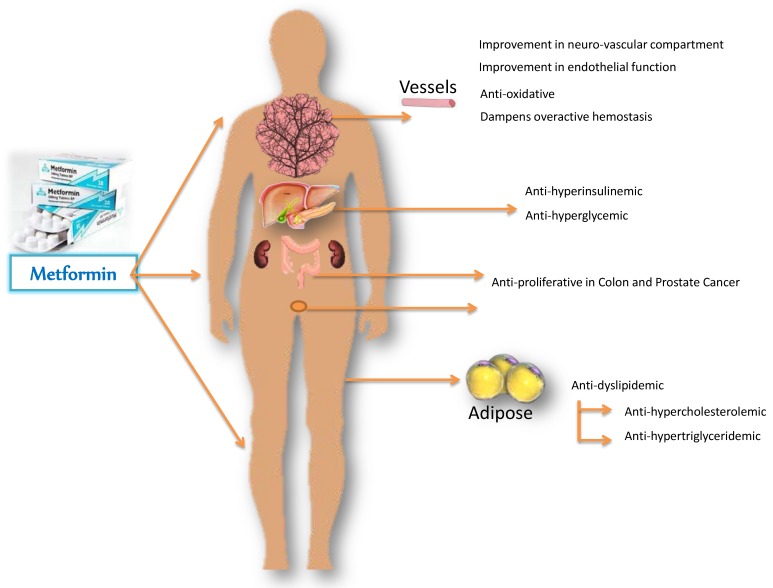

Figure 1.

Metformin-mediated amelioration in diabetic and cancerous deranged metabolic profile, improvements in hemostasis and endothelial function, with regression of proliferative state. Metformin acts primarily on the liver and reduces glucose output, and secondarily on the peripheral tissues to increase glucose uptake. By decreasing gluconeogenesis, it ameliorates hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, improves endothelial function, oxidative stress, insulin resistance and fat redistribution. Accumulating evidence supports the antiproliferative role of metformin in colon and prostate cancer.

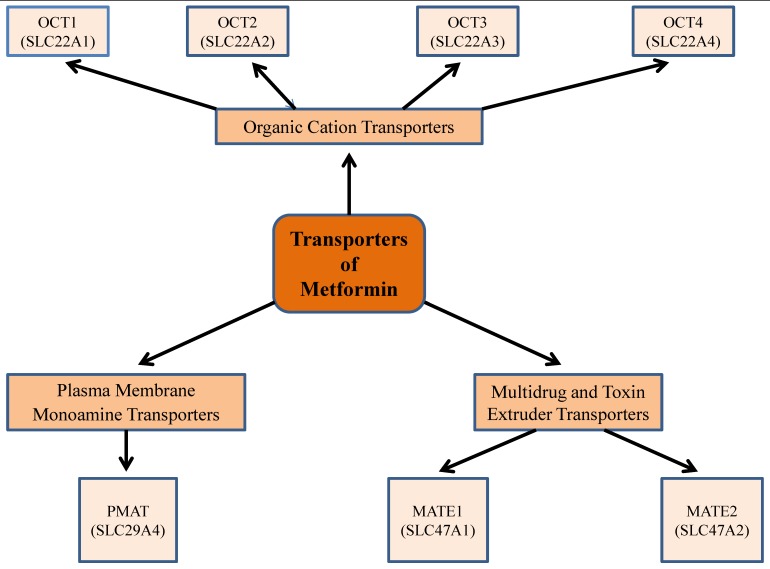

Information on the pharmacological response to metformin requires an understanding of both its pharmacokinetics and genetic variation of the different transporters for the di-directional movement of metformin across plasma membranes 17 (Fig.2). Metformin is absorbed from the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract (GI) through plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT, or equilibrative nucleoside transporter-ENT-4) 18. By its passage through the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1), located in the basolateral membrane of human hepatocytes, metformin decreases hepatic glucose synthesis 19. Indeed, this was confirmed by investigations on OCT1 gene-deficient mice, where the uptake of metformin in hepatic and intestinal tissues was lower, compared to control animals 19. These studies implied that OCT1 is pivotal for raising the intracellular concentration of metformin; and as a corollary, there was a corresponding derangement in glucose metabolism 19. Interestingly, metformin is excreted unmetabolized through mutli-drug and toxin extrusion 1 (MATE1) and MATE2, located in the apical membrane of kidney proximal tubular cells, into urine 20. Recent studies suggest that substantial inter-individual heterogeneity in metformin pharmacokinetics exists, and this is recognized to be due to genetic variants of different metformin transporter proteins 20-22. Reduced expression or altered functionality of transporter proteins will result in less than optimum pharmacotherapy or undesirable toxic effects of metformin.

Figure 2.

Metformin transporters: Isoforms and genes that demonstrate a role in metformin pharmacokinetics, pharmacogenetics, and thus have an impact on its pharmacological efficacy. Metformin is absorbed from the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract through plasma membrane monoamine transporter (PMAT). It requires the organic cation transporters (OCTs), located in the basolateral membrane of human hepatocytes, to be transported into the liver, thus decreasing hepatic glucose synthesis. The multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 and 2 (MATE1 and MATE2), located in the apical membrane of kidney proximal tubular cells, facilitate metformin excretion into urine. Genetic variation in transporter genes may alter transporter expression and functionality and thus metformin response.

Due to the reduced uptake of glucose from the intestinal tract, metformin improves insulin sensitivity by increasing peripheral glucose absorption and utilization by adipose tissue and skeletal muscle. It reduces hyperinsulinemia and improves insulin resistance by enhancing the affinity of insulin receptor for insulin 23. Moreover, metformin-driven benefits negate dyslipidemia by creating a milieu to give rise to lower circulating levels of total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and triglycerides 24. In addition, administration of metformin to patients promotes lower body weight or at least weight neutrality 25, 26. Importantly, metformin is a low cost drug with a well characterized safety profile in management of diabetes and cancer.

3. Pleiotropic effects of metformin

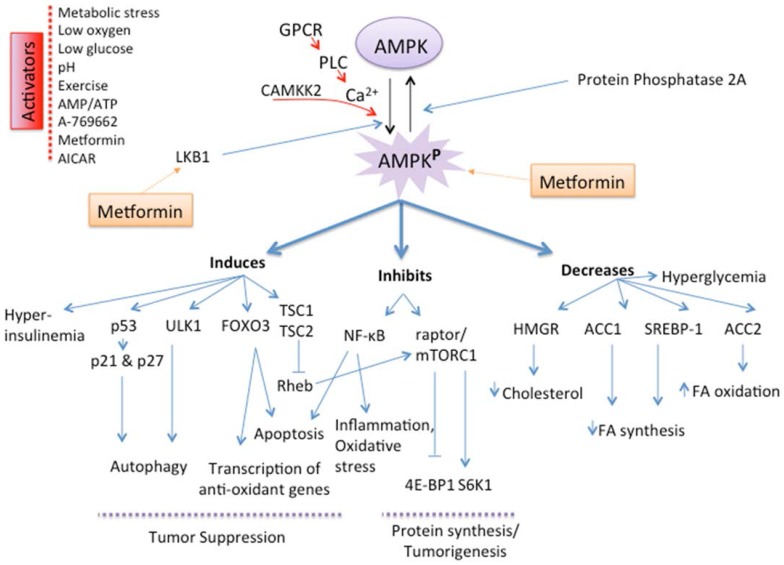

Multifactorial mechanisms account for metformin's therapeutic contribution to its anti-oncogenic properties. Metformin inhibits complex 1 of mitochondrial electron transport chain 27-29, and thereby attenuates oxidative respiration resulting in ATP/AMP ratio imbalance, which in turn activates liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and AMPK 29, 30. Dephosphorylation by protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) reversibly decreases enzyme efficiency (inactivation) of AMPK. Interestingly, metformin interplay with cellular metabolic homeostasis extends to inhibition of AMP deaminase to increase the pool of AMP available for activation of AMPK 31. Thus, AMPK can choreograph a network of diverse molecular signaling routes depending on the contextual requirements for physiological cellular homeostasis and/or pathophysiological states (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Mechanism and Role of AMPK activation. AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a serine/threonine kinase, is an energy sensor whose activity is regulated by glucose. AMPK activation, secondary to a change in the AMP/ATP ratio, activation by upstream kinases, such as CAMKK (CaMK kinase) and LKB1, or administration of metformin by direct activation of LKB1, slows metabolic reactions that consume ATP and stimulates reactions that produce ATP, thereby restoring the AMP/ATP ratio and the normal cellular energy stores. AMPK activation will in turn induce catabolic pathways, such as fatty acid oxidation by inactivating acetyl CoA carboxylase (ACC2), and will inhibit anabolic pathways, such as fatty acid synthesis, mediated by ACC1. The mTOR pathway suppresses apoptosis via its effect on the tumor suppressors p53 and p27 and inhibits autophagy by suppressing UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) and ULK2. AMPK activation downregulates the tumorigenic effects of mTOR through the TSC1/TSC2 complex, thus leading to increased apoptosis and autophagy-mediated cell death. AMPK activation also inactivates P70S6K and 4E-BP1 subsequently inhibiting protein synthesis. AMPK activation regulates the transcription factor FOXO3, which in turn increases antioxidant gene expression.

4. Regulation of Energy Homeostasis

Metformin acts cooperatively with the upstream kinase LKB1 to activate AMPK, the master regulator of metabolic homeostasis, resulting in the attenuation of plasma concentrations of risk factors, namely glucose, insulin, triglycerides and cholesterol 9, 32, 33. Metformin, via AMPK, controls the activity and expression of key regulatory lipid enzymes that have been identified in metabolic reprogramming of cancers. Phosphorylated AMPK, by upstream metformin-mediated effect, markedly reduces the expression (mRNA and protein) of lipogenic transcription factor sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) and hence its targeted genes are also downregulated such as fatty acid synthase (FAS) 30, 34, and 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR, membrane-bound enzyme), which is known to reduce HMG-CoA to mevalonate 35. In addition, AMPK directly inactivates HMGR by phosphorylation at serine 872, thus essentially abating cholesterol synthesis 36. Also, statins, which are reportedly used for anti-cancer therapy, lower cholesterol by inhibiting HMGR 37-39, which is up-regulated in many forms of cancers 40. Moreover, the activated form of AMPK alters the activity of another type of lipogenic enzyme, acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), which exists in two isoforms: ACC1 (ACC-α) and ACC2 (ACC-β). Phosphorylation of AAC1 switches on fatty acid synthesis through its metabolite malonyl-CoA, while ACC2 controls fatty acid oxidation 41. Contextually of interest is the silencing by small interfering RNA (siRNA) of ACC1 gene that leads to growth arrest and caspase-dependent apoptosis of the human lipogenic LNCaP prostate cancer cell line 42. Altogether, these inhibitory signaling arrays of metabolic activity mitigate the burden of cancer-promoting effect of high fat diets.

5. Cell cycle arrest and anti-proliferative activity

Cellular growth-retarding contributions of metformin occur downstream from activation of LKB1/AMPK pathway, inhibition of mTOR, stabilization of the transcription factor p53 (its degradation is suppressed with downregulation of cyclin D1 43 and associated increases in the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p27Kip1 and p21Cip1 44. The transcription factor p53 contributes to p21 gene transcription; and up-regulates the expression of apoptotic genes (Bax, Caspase-3, 8, 9) 45. These molecular signaling events channel cells to latency and hence drive them to accumulate in the Go/G1 cell cycle phase; DNA-damage and fragmentation ensues, leading to tumor suppression and further to autophagy and/or apoptosis 46. In addition, metformin-activated AMPK phosphorylates ULK1 at serines 317 and 777 to ultimately induce mitophagy, autophagy as well as cell death, and subsequently apoptosis and reduction of tumor size 47, 48. Furthermore, NF-κB is a transcription factor associated with apoptosis, inflammation, oxidative stress and neoplastic malignancy, which are all inhibited by metformin-stimulated AMPK 48-51. Evidently all of this is reflected by the aforementioned investigations on cell lines, animal models and beneficial survival outcomes of therapeutic intervention studies with metformin for cancer-related patients with T2DM.

Antiproliferative actions of AMPK, activated by metformin, suppress the growth of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) 52 as well as human and rat aortic smooth muscle cells 16, 53, thus preventing tumor angiogenesis 54. Intuitively, this will lead to starving of the tumor of nutrients, thereby limiting biosynthetic processes for macromolecules and hence cell growth for malignancy. Therefore, such multi-actions of AMPK suppress tumors with greater efficacy. Also, AMPK directly phosphorylates TSC2 tumor suppressor (phosphorylated at dual locations: threonine 1227 and serine 1345 55 and raptor (regulatory-associated protein of mTOR, phosphorylated at serines 722 and 792) 56, a constituent subunit of mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin), to suppress mTORC1 activity 55, 56. Moreover, metformin directly interacts with mTORC1 to inhibit its effects downstream, the ribosomal protein S6, S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) and the translation initiation factor 4E binding protein 1 (4E-BP1), and again this induces cell cycle arrest and inhibits DNA synthesis 57.

6. Regulation of oxidative stress

Metformin arrests hyperinsulinemia-induced free radicals (superoxide anion radical, hydroxyl radicals) and reactive oxygen species (ROS, hydrogen peroxide), which are integral to oxidative stress (imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants) and play an active mechanistic role in most cancers, and cell death is associated with generation of ROS 50, 58-61. AMPK in conjunction with the transcription factor FOXO3 lessens the fatty acid-induced generation of intracellular ROS by up-regulating the expression of the antioxidant thioredoxin 62-64, and the reduction in NADPH oxidase activity 65. In contrast, reactive oxygen species, such as hydrogen peroxide, significantly activates the AMPKα sub-unit to inhibit mTORC1 signaling and induce apoptosis 66.

7. Evidence from animal models and clinical trials

Taken together, this implies that metformin may lower cancer risk owing to its inherent properties of improving an altered metabolic picture, which is reflected by a fall in plasma glucose and insulin concentrations 32. Evidence from a panel of cancer cell lines 43, 67, 68, animal models 43, 68, 69 and epidemiological studies 70-73 suggests that metformin not only improves the life style and well-being, but lowers the rates of mortality in CRC 74 and PC 75. Multi-ethnic epidemiological studies have revealed disparity between ethnic groups of patients with PC risk due to diabetes and/or different medication (metformin) 6, 73, 75. However, in one of the latter meta-analysis studies on PC, the authors added a caveat that additional long-term investigations on the use of metformin for PC must be forthcoming for concrete confirmation of the available data 75. Appropriately, triggered by these promising anti-tumorigenic benefits of metformin, epidemiologists have initiated clinical trials centered on a variety of tumors, including colorectal (5 ongoing clinical trials) and prostate (3 ongoing clinical trials) cancers with diabetes, and these can be located at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ website.

Continuing from above, recent evidence has commenced a debate on whether AMPK is a suppressor of cancer or an oncogenic member of signaling cascade 76, 77. This is perhaps an issue of the extent of AMPK activation, where at low activity it may not be a potent anti-cancer agent, but sustained high activation may be critical for inhibition on growth and survival of tumors. In the same context, it is not clear from the literature if any dose response curves for metformin as a chemotherapeutic agent have been performed on AMPK activity. Consideration must be given to the subject of genetic polymorphism of organic cation transporters (OCT1 and OCT2), which may affect the population-based individual variability and hence clinical efficacy of metformin 78. Therefore, this necessitates further studies to ensure and to consolidate that the thesis on metformin-activated AMPK is water-tight as an inhibitor of proliferative growth in cancers.

To conclude, recent advances in pinpointing the molecular control points that orchestrate the myriad of transduction pathways is pivotal to personalized therapy for cancer and other treatments, and the metformin research has rightly focused on AMPK, the master metabolic sensor. On a cautionary note, tumors are heterogeneous by character, and as Mother Nature has its own surprises, therefore it may be prudent to target more than one molecule as this approach may be more efficacious. Overall though, the preceding statements confirm that metformin is as a mono-therapeutic agent with multi-fold targets (Table 1 and 2).

Table 1.

From Bench to Bedside: the use of metformin from cultured cells to clinical trials.

| Cell lines | Animal Studies | Clinical Trials | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a). Xiang X, Saha AK, Wen R, Ruderman NB, Luo Z, 2004. AMP-activated protein kinase activators can inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells by multiple mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 321:161-167. | a). Buzzai M, Jones RG, Amaravadi RK, Lum JJ, DeBerardinis RJ, Zhao F, Viollet B & Thompson CB 2007 Systemic treatment with the antidiabetic drug metformin selectively impairs p53-deficient tumor cell growth. Cancer Research 67 6745-6752. | i). Search identifier at clinicaltrial.gov/ Metformin/colorectal cancer/diabetes | ||

| b). Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Colosetti P, Auberger P, Tanti JF, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Bost F, (2008). The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene 27(25):3576-3586. Proliferation of DU145, PC-3, LNCaP cancer cells; xenografts of LNCaP, reduction of cyclin D1 protein level | b). Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Colosetti P, Auberger P, Tanti JF, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Bost F, (2008). The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene 27(25):3576-3586. | Status | Study | Clinical trials. gov identifier |

| c). Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Giuliano S, et al. Targeting cancer cell metabolism: the combination of metformin and 2-deoxyglucose induces p53-dependent apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Research 2010;70:2465-75. | c). Huang X, Wullschleger S, Shpiro N, McGuire VA, Sakamoto K, Woods YL, McBurnie W, Fleming S, Alessi DR. Important role of the LKB1-AMPK pathway in suppressing tumorigenesis in PTEN-deficient mice. Biochem J. 2008 Jun 1;412(2):211-21. | Recruiting | Exercise and Metformin in Colorectal and breast cancer Survivors | NCT01340300 |

| d). Zakikhani, M., Dowling, R.J., Sonenberg, N., Pollak, M.N., (2008). The effects of adiponectin and metformin on prostate and colon neoplasia involve activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 1: 369-375. Metformin-mediated AMPK activation decrease cell growth and protein synthesis | d). Tomimoto A, Endo H, Sugiyama M, Fujisawa T, Hosono K, Takahashi H, Nakajima N, Nagashima Y, Wada K, Nakagama H et al. 2008 Metformin suppresses intestinal polyp growth in ApcMin/C mice. Cancer Science 99 2136-2141. | Recruiting | Impact of pretreatment with Metformin on colorectal cancer Stem cells (CCSC) and related Pharmacodynamics markers | NCT01440127 |

| e). Algire C, Amrein L, Zakikhani M, Panasci L, Pollak M. Metformin blocks the stimulative effect of a high-energy diet on colon carcinoma growth in vivo and is associated with reduced expression of fatty acid synthase. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010 Jun 1;17(2):351-60. | Recruiting | An open-labeled pilot study of biomarker response following short-term exposure to metformin | NCT01816659 | |

| f). Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, Sugiyama M, Uchiyama T, Suzuki K, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Fujita K, Yoneda M, Inamori M, Tomatsu A, Chihara T, Shimpo K, Nakagama H, Nakajima A, 2010. Metformin suppresses azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Carcinog. 49:662-671. | Not yet recruiting | The chemopreventive effect of Metformin in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis: double blinded randomized controlled study | NCT01725490 | |

| ii). Search identifier at clinicaltrial.gov/ Metformin/prostate cancer/diabetes | ||||

| Status | Study | Clinical trials. gov identifier | ||

| Recruiting | Metformin-Docetaxel Association Colorectal and breast cancer Survivors | NCT01796028 | ||

| Active not recruiting | Metformin in castration - resistant Metformin on colorectal cancer Stem cells (CCSC) and related Pharmacodynamics markers | NCT01215032 | ||

| Recruiting | Castration compared to castration Plus metformin as first line treatment For patients with advanced prostate cancer | NCT01620593 | ||

Table 2.

Epidemiological Investigations.

| a) Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR & Morris AD 2005 Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. BMJ 330 1304-1305. |

| b) Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A, 2005. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 97:1679-1687. |

| c) Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P & Johnson JA 2006 Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care 29 254-258. |

| d) Kasper JS, Giovannucci E. A meta-analysis of diabetes mellitus and the risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:2056-62. |

| e) Kasper JS, Liu Y, Giovannucci E. Diabetes mellitus and risk of prostate cancer in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer. 2009 Mar 15;124(6):1398-403. |

| f) Libby G, Donnelly LA, Donnan PT, Alessi DR, Morris AD, Evans JM. New users of metformin are at low risk of incident cancer: a cohort study among people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32:1620-5. |

| g) Wright, J.L., Stanford, J.L., 2009. Metformin use and prostate cancer in Caucasian men: results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control 20: 1617-1622. |

| h) Decensi A, Puntoni M, Goodwin P, Cazzaniga M, Gennari A, Bonanni B, Gandini S. Metformin and cancer risk in diabetic patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010 Nov;3(11):1451-61. |

| i). Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, Sugiyama M, Sakai E, Uchiyama T, Suzuki K, Iida H, Sakamoto Y, Yoneda K, Koide T, Tokoro C, Abe Y, Inamori M, Nakagama H, Nakajima A. Metformin suppresses colorectal aberrant crypt foci in a short-term clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2010 Sep;3(9):1077-83. |

| j) Landman GW, Kleefstra N, van Hateren KJ, Groenier KH, Gans RO, Bilo HJ. Metformin associated with lower cancer mortality in type 2 diabetes: ZODIAC-16. Diabetes Care. 2010 Feb;33(2):322-6. |

| k). Azoulay L, Dell'Aniello S, Gagnon B, Pollak M, Suissa S. Metformin and the incidence of prostate cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011 Feb;20(2): 337-44. - this study indicates that metformin does not reduce the risk of prostate cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes. |

| l). Lee MS, Hsu CC, Wahlqvist ML, et al. Type 2 diabetes increases and metformin reduces total, colorectal, liver and pancreatic cancer incidences in Taiwanese: a representative population prospective cohort study of 800,000 individuals. BMC Cancer 2011;11:20 |

| m) Monami M, Colombi C, Balzi D, et al. Metformin and cancer occurrence in insulin-treated type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2011;34:129-131 |

| n) Zhang ZJ, Zheng ZJ, Kan H, Song Y, Cui W, Zhao G, Kip KE. Reduced risk of colorectal cancer with metformin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2011 Oct;34(10):2323-8. |

| o) Deng L, Gui Z, Zhao L, Wang J, Shen L, 2012. Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 57: 1576-1585. |

| p) Garrett CR, Hassabo HM, Bhadkamkar NA, Wen S, Baladandayuthapani V, Kee BK, Eng C, Hassan MM. Survival advantage observed with the use of metformin in patients with type II diabetes and colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2012 Apr 10;106(8):1374-8. |

| q) Higurashi T, Takahashi H, Endo H, Hosono K, Yamada E, Ohkubo H, Sakai E, Uchiyama T, Hata Y, Fujisawa N, Uchiyama S, Ezuka A, Nagase H, Kessoku T, Matsuhashi N, Yamanaka S, Inayama Y, Morita S, Nakajima A. Metformin efficacy and safety for colorectal polyps: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2012 Mar 26; 12: 118. |

| r) Lee JH, Jeon SM, Hong SP, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH. Metformin use is associated with a decreased incidence of colorectal adenomas in diabetic patients with previous colorectal cancer. Dig Liver Dis. 2012 Dec;44(12):1042-7. |

| s) Lee, J.H., Kim II, T., Jeon, S.M., Hong, S.P., Cheon, J.H., Kim, W.H., 2012. The effects of metformin on the survival of colorectal cancer patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Cancer 131: 752-759. |

| t) Noto H, Goto A, Tsujimoto T, Noda M (2012). Cancer risk in diabetic patients treated with metformin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 7: e33411. |

| u) Ruiter R, Visser LE, van Herk-Sukel MP, Coebergh JW, Haak HR, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Straus SM, Herings RM, Stricker BH, 2012. Lower risk of cancer in patients on metformin in comparison with those on sulfonylurea derivatives: Results from a large population-based follow-up study. Diabetes Care 35: 119-124. |

| v) Soranna D, Scotti L, Zambon A, Bosetti C, Grassi G, Catapano A, La Vecchia C, Mancia G, Corrao G. Cancer risk associated with use of metformin and sulfonylurea in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Oncologist. 2012;17(6):813-22. |

| w). Chung HH, Moon JS, Yoon JS, Lee HW, Won KC. The Relationship between Metformin and Cancer in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Metab J. 2013 Apr;37(2): 125-31. |

8. Perspectives

Although an arsenal of therapeutic drugs is available for the management of different categories of cancer with type 2 diabetes mellitus, metformin remains the most widely used medication for T2DM. Recently, AMPK has received considerable attention regarding its central role as a metabolic homeostasis sustaining rheo-transducer as well as an inter-link between signaling routes between diabetes and cancer. Further preclinical and clinical investigations are ongoing to evaluate the therapeutic benefits of metformin on AMPK activation as an anti-diabetic, anti-proliferative, hypoinsulinemic, apoptotic and hence anti-carcinogenic agent. Indeed, results with metformin demonstrate that AMPK is an ideal target for activation in both CRC and PC, and moreover metformin has other beneficial pleotropic targets in addition to metabolic control. In this context, and considering the afore-mentioned paragraphs, its effects on aberrant homeostasis in T2DM, CRC and PC are truly remarkable. Hence, it potentially holds substantial promise as a positive dual modifier of deranged metabolic homeostasis and as an anti-neoplastic agent.

Acknowledgments

This publication was made possible by grant # NPRP 5-409-3-112 from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of Qatar Foundation). The Statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

This grant was awarded to Drs. Assaad A. Eid and Ali H. Eid

References

- 1.Nelson WG, Yegnasubramanian S, Agoston AT, Bastian PJ, Lee BH, Nakayama M, De Marzo AM. Abnormal DNA methylation, epigenetics, and prostate cancer. Front Biosci. 2007;12:4254–66. doi: 10.2741/2385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lambert MP, Herceg Z. Epigenetics and cancer, 2nd IARC meeting, Lyon, France, 6 and 7 December 2007. Mol Oncol. 2008;2(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.03.005. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crea F, Nobili S, Paolicchi E, Perrone G, Napoli C, Landini I, Danesi R, Mini E. Epigenetics and chemoresistance in colorectal cancer: an opportunity for treatment tailoring and novel therapeutic strategies. Drug Resist Updat. 2011;14(6):280–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.08.001. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Larsson SC, Orsini N, Wolk A. Diabetes mellitus and risk of colorectal cancer: a meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(22):1679–87. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji375. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasper JS, Liu Y, Giovannucci E. Diabetes mellitus and risk of prostate cancer in the health professionals follow-up study. Int J Cancer. 2009;124(6):1398–403. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24044. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waters KM, Henderson BE, Stram DO, Wan P, Kolonel LN, Haiman CA. Association of diabetes with prostate cancer risk in the multiethnic cohort. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169(8):937–45. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp003. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deng L, Gui Z, Zhao L, Wang J, Shen L. Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of colorectal cancer: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57(6):1576–85. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2055-1. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim YI. Diet, lifestyle, and colorectal cancer: is hyperinsulinemia the missing link? Nutr Rev. 1998;56(9):275–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1998.tb01765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inzucchi SE. Oral antihyperglycemic therapy for type 2 diabetes: scientific review. Jama. 2002;287(3):360–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esposito K, Chiodini P, Colao A, Lenzi A, Giugliano D. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(11):2402–11. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0336. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aleksandrova K, Nimptsch K, Pischon T. Influence of Obesity and Related Metabolic Alterations on Colorectal Cancer Risk. Curr Nutr Rep. 2013;2(1):1–9. doi: 10.1007/s13668-012-0036-9. doi: 10.1007/s13668-012-0036-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anisimov VN, Berstein LM, Egormin PA, Piskunova TS, Popovich IG, Zabezhinski MA, Kovalenko IG, Poroshina TE, Semenchenko AV, Provinciali M. et al. Effect of metformin on life span and on the development of spontaneous mammary tumors in HER-2/neu transgenic mice. Exp Gerontol. 2005;40(8-9):685–93. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.007. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Witters LA. The blooming of the French lilac. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(8):1105–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI14178. doi: 10.1172/JCI14178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saenz A, Fernandez-Esteban I, Mataix A, Ausejo M, Roque M, Moher D. Metformin monotherapy for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005(3):CD002966. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002966.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Caballero AE, Delgado A, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Herrera AN, Castillo JL, Cabrera T, Gomez-Perez FJ, Rull JA. The differential effects of metformin on markers of endothelial activation and inflammation in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance: a placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(8):3943–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0019. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim SA, Choi HC. Metformin inhibits inflammatory response via AMPK-PTEN pathway in vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;425(4):866–72. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.165. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham GG, Punt J, Arora M, Day RO, Doogue MP, Duong JK, Furlong TJ, Greenfield JR, Greenup LC, Kirkpatrick CM. et al. Clinical pharmacokinetics of metformin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2011;50(2):81–98. doi: 10.2165/11534750-000000000-00000. doi: 10.2165/11534750-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou M, Xia L, Wang J. Metformin transport by a newly cloned proton-stimulated organic cation transporter (plasma membrane monoamine transporter) expressed in human intestine. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35(10):1956–62. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015495. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shu Y, Sheardown SA, Brown C, Owen RP, Zhang S, Castro RA, Ianculescu AG, Yue L, Lo JC, Burchard EG. et al. Effect of genetic variation in the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) on metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(5):1422–31. doi: 10.1172/JCI30558. doi: 10.1172/JCI30558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stocker SL, Morrissey KM, Yee SW, Castro RA, Xu L, Dahlin A, Ramirez AH, Roden DM, Wilke RA, McCarty CA. et al. The effect of novel promoter variants in MATE1 and MATE2 on the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of metformin. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93(2):186–94. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.210. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen L, Takizawa M, Chen E, Schlessinger A, Segenthelar J, Choi JH, Sali A, Kubo M, Nakamura S, Iwamoto Y. et al. Genetic polymorphisms in organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) in Chinese and Japanese populations exhibit altered function. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;335(1):42–50. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170159. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.170159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer zu Schwabedissen HE, Verstuyft C, Kroemer HK, Becquemont L, Kim RB. Human multidrug and toxin extrusion 1 (MATE1/SLC47A1) transporter: functional characterization, interaction with OCT2 (SLC22A2), and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2010;298(4):F997–F1005. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00431.2009. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00431.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ashokkumar N, Pari L, Rao Ch A. Effect of N-benzoyl-D-phenylalanine and metformin on insulin receptors in neonatal streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: studies on insulin binding to erythrocytes. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2006;112(3):174–81. doi: 10.1080/13813450600935339. doi: 10.1080/13813450600935339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bailey CJ, Turner RC. Metformin. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(9):574–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340906. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harborne LR, Sattar N, Norman JE, Fleming R. Metformin and weight loss in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome: comparison of doses. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4593–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2283. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-2283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rojas LB, Gomes MB. Metformin: an old but still the best treatment for type 2 diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2013;5(1):6.. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-6. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Mir MY, Nogueira V, Fontaine E, Averet N, Rigoulet M, Leverve X. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an indirect effect targeted on the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(1):223–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owen MR, Doran E, Halestrap AP. Evidence that metformin exerts its anti-diabetic effects through inhibition of complex 1 of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. Biochem J. 2000. 348 Pt 3:607-14. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Viollet B, Guigas B, Sanz Garcia N, Leclerc J, Foretz M, Andreelli F. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of metformin: an overview. Clin Sci (Lond) 2012;122(6):253–70. doi: 10.1042/CS20110386. doi: 10.1042/CS20110386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou G, Myers R, Li Y, Chen Y, Shen X, Fenyk-Melody J, Wu M, Ventre J, Doebber T, Fujii N. et al. Role of AMP-activated protein kinase in mechanism of metformin action. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(8):1167–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. doi: 10.1172/JCI13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ouyang J, Parakhia RA, Ochs RS. Metformin activates AMP kinase through inhibition of AMP deaminase. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(1):1–11. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.121806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ruiter R, Visser LE, van Herk-Sukel MP, Coebergh JW, Haak HR, Geelhoed-Duijvestijn PH, Straus SM, Herings RM, Stricker BH. Lower risk of cancer in patients on metformin in comparison with those on sulfonylurea derivatives: results from a large population-based follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):119–24. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0857. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hardie DG, Alessi DR. LKB1 and AMPK and the cancer-metabolism link - ten years after. BMC Biol. 2013;11:36.. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-36. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-11-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Algire C, Amrein L, Zakikhani M, Panasci L, Pollak M. Metformin blocks the stimulative effect of a high-energy diet on colon carcinoma growth in vivo and is associated with reduced expression of fatty acid synthase. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2010;17(2):351–60. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0252. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldstein JL, DeBose-Boyd RA, Brown MS. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 2006;124(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke PR, Hardie DG. Regulation of HMG-CoA reductase: identification of the site phosphorylated by the AMP-activated protein kinase in vitro and in intact rat liver. Embo J. 1990;9(8):2439–46. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07420.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endo A, Kuroda M, Tanzawa K. Competitive inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase by ML-236A and ML-236B fungal metabolites, having hypocholesterolemic activity. FEBS Lett. 1976;72(2):323–6. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(76)80996-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Istvan ES. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. Am Heart J. 2002;144(6 Suppl):S27–32. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.130300. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2002.130300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Istvan ES, Deisenhofer J. Structural mechanism for statin inhibition of HMG-CoA reductase. Science. 2001;292(5519):1160–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1059344. doi: 10.1126/science.1059344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Notarnicola M, Messa C, Pricci M, Guerra V, Altomare DF, Montemurro S, Caruso MG. Up-regulation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase activity in left-sided human colon cancer. Anticancer Res. 2004;24(6):3837–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hardie DG, Pan DA. Regulation of fatty acid synthesis and oxidation by the AMP-activated protein kinase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(Pt 6):1064–70. doi: 10.1042/bst0301064. doi: 10.1042/ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brusselmans K, De Schrijver E, Verhoeven G, Swinnen JV. RNA interference-mediated silencing of the acetyl-CoA-carboxylase-alpha gene induces growth inhibition and apoptosis of prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65(15):6719–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0571. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ben Sahra I, Laurent K, Loubat A, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Colosetti P, Auberger P, Tanti JF, Le Marchand-Brustel Y, Bost F. The antidiabetic drug metformin exerts an antitumoral effect in vitro and in vivo through a decrease of cyclin D1 level. Oncogene. 2008;27(25):3576–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211024. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1211024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhuang Y, Miskimins WK. Cell cycle arrest in Metformin treated breast cancer cells involves activation of AMPK, downregulation of cyclin D1, and requires p27Kip1 or p21Cip1. J Mol Signal. 2008;3:18.. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-3-18. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyashita T, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human bax gene. Cell. 1995;80(2):293–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang J, Shao SH, Xu ZX, Hennessy B, Ding Z, Larrea M, Kondo S, Dumont DJ, Gutterman JU, Walker CL. et al. The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27(kip1) phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(2):218–24. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Egan DF, Shackelford DB, Mihaylova MM, Gelino S, Kohnz RA, Mair W, Vasquez DS, Joshi A, Gwinn DM, Taylor R. et al. Phosphorylation of ULK1 (hATG1) by AMP-activated protein kinase connects energy sensing to mitophagy. Science. 2011;331(6016):456–61. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. doi: 10.1126/science.1196371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim J, Kundu M, Viollet B, Guan KL. AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13(2):132–41. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Batandier C, Guigas B, Detaille D, El-Mir MY, Fontaine E, Rigoulet M, Leverve XM. The ROS production induced by a reverse-electron flux at respiratory-chain complex 1 is hampered by metformin. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2006;38(1):33–42. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9003-8. doi: 10.1007/s10863-006-9003-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sena CM, Matafome P, Louro T, Nunes E, Fernandes R, Seica RM. Metformin restores endothelial function in aorta of diabetic rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(2):424–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01230.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01230.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kita Y, Takamura T, Misu H, Ota T, Kurita S, Takeshita Y, Uno M, Matsuzawa-Nagata N, Kato K, Ando H. et al. Metformin prevents and reverses inflammation in a non-diabetic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e43056.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peyton KJ, Liu XM, Yu Y, Yates B, Durante W. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits the proliferation of human endothelial cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;342(3):827–34. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.194712. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.194712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Igata M, Motoshima H, Tsuruzoe K, Kojima K, Matsumura T, Kondo T, Taguchi T, Nakamaru K, Yano M, Kukidome D. et al. Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase suppresses vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation through the inhibition of cell cycle progression. Circ Res. 2005;97(8):837–44. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000185823.73556.06. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000185823.73556.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Soraya H, Esfahanian N, Shakiba Y, Ghazi-Khansari M, Nikbin B, Hafezzadeh H, Maleki Dizaji N, Garjani A. Anti-angiogenic Effects of Metformin, an AMPK Activator, on Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells and on Granulation Tissue in Rat. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2012;15(6):1202–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shaw RJ. LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase control of mTOR signalling and growth. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;196(1):65–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01972.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30(2):214–26. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kalender A, Selvaraj A, Kim SY, Gulati P, Brule S, Viollet B, Kemp BE, Bardeesy N, Dennis P, Schlager JJ. et al. Metformin, independent of AMPK, inhibits mTORC1 in a rag GTPase-dependent manner. Cell Metab. 2010;11(5):390–401. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Goetz ME, Luch A. Reactive species: a cell damaging rout assisting to chemical carcinogens. Cancer Lett. 2008;266(1):73–83. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.035. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.02.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Piwkowska A, Rogacka D, Jankowski M, Dominiczak MH, Stepinski JK, Angielski S. Metformin induces suppression of NAD(P)H oxidase activity in podocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393(2):268–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.119. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.01.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Block K, Gorin Y. Aiding and abetting roles of NOX oxidases in cellular transformation. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(9):627–37. doi: 10.1038/nrc3339. doi: 10.1038/nrc3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee EK, Jeong JU, Chang JW, Yang WS, Kim SB, Park SK, Park JS, Lee SK. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase inhibits albumin-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis through inhibition of reactive oxygen species. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2012;121(1-2):e38–48. doi: 10.1159/000342802. doi: 10.1159/000342802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Greer EL, Oskoui PR, Banko MR, Maniar JM, Gygi MP, Gygi SP, Brunet A. The energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase directly regulates the mammalian FOXO3 transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(41):30107–19. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705325200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li XN, Song J, Zhang L, LeMaire SA, Hou X, Zhang C, Coselli JS, Chen L, Wang XL, Zhang Y. et al. Activation of the AMPK-FOXO3 pathway reduces fatty acid-induced increase in intracellular reactive oxygen species by upregulating thioredoxin. Diabetes. 2009;58(10):2246–57. doi: 10.2337/db08-1512. doi: 10.2337/db08-1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hou X, Song J, Li XN, Zhang L, Wang X, Chen L, Shen YH. Metformin reduces intracellular reactive oxygen species levels by upregulating expression of the antioxidant thioredoxin via the AMPK-FOXO3 pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;396(2):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.017. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song P, Zou MH. Regulation of NAD(P)H oxidases by AMPK in cardiovascular systems. Free Radic Biol Med. 2012;52(9):1607–19. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.025. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen L, Xu B, Liu L, Luo Y, Yin J, Zhou H, Chen W, Shen T, Han X, Huang S. Hydrogen peroxide inhibits mTOR signaling by activation of AMPKalpha leading to apoptosis of neuronal cells. Lab Invest. 2010;90(5):762–73. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.36. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Xiang X, Saha AK, Wen R, Ruderman NB, Luo Z. AMP-activated protein kinase activators can inhibit the growth of prostate cancer cells by multiple mechanisms. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;321(1):161–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zakikhani M, Dowling RJ, Sonenberg N, Pollak MN. The effects of adiponectin and metformin on prostate and colon neoplasia involve activation of AMP-activated protein kinase. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2008;1(5):369–75. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0081. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, Sugiyama M, Sakai E, Uchiyama T, Suzuki K, Iida H, Sakamoto Y, Yoneda K. et al. Metformin suppresses colorectal aberrant crypt foci in a short-term clinical trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2010;3(9):1077–83. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0186. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Evans JM, Donnelly LA, Emslie-Smith AM, Alessi DR, Morris AD. Metformin and reduced risk of cancer in diabetic patients. Bmj. 2005;330(7503):1304–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38415.708634.F7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bowker SL, Majumdar SR, Veugelers P, Johnson JA. Increased cancer-related mortality for patients with type 2 diabetes who use sulfonylureas or insulin. Diabetes Care. 2006;29(2):254–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.02.06.dc05-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hosono K, Endo H, Takahashi H, Sugiyama M, Uchiyama T, Suzuki K, Nozaki Y, Yoneda K, Fujita K, Yoneda M. et al. Metformin suppresses azoxymethane-induced colorectal aberrant crypt foci by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. Mol Carcinog. 2010;49(7):662–71. doi: 10.1002/mc.20637. doi: 10.1002/mc.20637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wright JL, Stanford JL. Metformin use and prostate cancer in Caucasian men: results from a population-based case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20(9):1617–22. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9407-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee JH, Kim TI, Jeon SM, Hong SP, Cheon JH, Kim WH. The effects of metformin on the survival of colorectal cancer patients with diabetes mellitus. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(3):752–9. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26421. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Noto H, Goto A, Tsujimoto T, Noda M. Cancer risk in diabetic patients treated with metformin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33411.. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jeon SM, Chandel NS, Hay N. AMPK regulates NADPH homeostasis to promote tumour cell survival during energy stress. Nature. 2012;485(7400):661–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11066. doi: 10.1038/nature11066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Liang J, Mills GB. AMPK: a contextual oncogene or tumor suppressor? Cancer Res. 2013;73(10):2929–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3876. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Takane H, Shikata E, Otsubo K, Higuchi S, Ieiri I. Polymorphism in human organic cation transporters and metformin action. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(4):415–22. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.4.415. doi: 10.2217/14622416.9.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]