Abstract

Introduction

Current surgical and ablative treatment options for prostate cancer have a relatively high incidence of side effects, which may diminish the quality of life. The side effects are a consequence of procedure-related damage of the blood vessels, bowel, urethra or neurovascular bundle. Ablation with irreversible electroporation (IRE) has shown to be effective in destroying tumour cells and harbours the advantage of sparing surrounding tissue and vital structures. The aim of the study is to evaluate the safety and efficacy and to acquire data on patient experience of minimally invasive, transperineally image-guided IRE for the focal ablation of prostate cancer.

Methods and analysis

In this multicentre pilot study, 16 patients with prostate cancer who are scheduled for a radical prostatectomy will undergo an IRE procedure, approximately 30 days prior to the radical prostatectomy. Data as adverse events, side effects, functional outcomes, pain and quality of life will be collected and patients will be controlled at 1 and 2 weeks post-IRE, 1 day preprostatectomy and postprostatectomy. Prior to the IRE procedure and the radical prostatectomy, all patients will undergo a multiparametric MRI and contrast-enhanced ultrasound of the prostate. The efficacy of ablation will be determined by whole mount histopathological examination, which will be correlated with the imaging of the ablation zone.

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol is approved by the ethics committee at the coordinating centre (Academic Medical Center (AMC) Amsterdam) and by the local Institutional Review Board at the participating centres. Data will be presented at international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Conclusions

This pilot study will determine the safety and efficacy of IRE in the prostate. It will show the radiological and histopathological effects of IRE ablations and it will provide data to construct an accurate treatment planning tool for IRE in prostate tissue.

Trial registration number

Clinicaltrials.gov database: NCT01790451.

Keywords: Irreversible electroporation, Focal therapy, Prostate cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The main strength of this study is the histopathological assessment of the ablation zone obtained by the radical prostatectomy (RP) specimen after the procedure. This outcome is of utmost importance in the evaluation of a new interventional device.

The quality of life of the participating patients will intensely be observed by validated questionnaires.

A limitation of this study is that ablations of the posterior peripheral zone directly adjacent to the rectum have to be avoided in order to minimise possible rectal damage.

Second, the maximum period between irreversible electroporation and RP in this trial is 4 weeks. This limits analysis of the histopathology beyond this timeframe.

Introduction

Current prostate cancer treatments can cause major side effects including urinary incontinence, erectile dysfunction and bowel urgency. These side effects occur due to damage of the (1) neurovascular bundles, (2) urethra including distal urethral smooth muscle sphincter, (3) puboprostatic ligaments and (4) rectum wall. To avoid damage to these structures, several ablative modalities have been introduced with the aim of effective cancer control without jeopardising functional outcomes. Preclinical studies with irreversible electroporation (IRE), a novel ablative modality, demonstrated an advantage over other focal therapies by effective ablation of tumour tissue, while sparing surrounding tissue and vital structures such as blood vessels, urethra and nerve bundles.1–3 It has been suggested that the potential of IRE to spare essential structures may help to reduce or even avoid side effects in the focal treatment of prostate cancer. Electroporation is a technique in which electric pulses, travelling between two or more electrodes, increase the permeability of the cellular membranes. This effect can either be reversible or irreversible. Reversible electroporation has been employed in electrochemotherapy to facilitate the uptake of chemotherapeutic agents into cells. The temporary damage to the cellular membrane allows the chemotherapeutic agent to enter the cell followed by recovery of the membrane.4 5 Damage becomes permanent above a certain threshold of electrical pulse length and kV/cm, which causes cell death due to the inability of the cell to maintain homoeostasis. Initially, the manifestation of this irreversible component during electroporation was considered an unwanted treatment side effect.6–8

In recent years, interest in IRE as a tumour ablation modality by inducing irreversible cell damage has risen. IRE has shown to be able to effectively ablate tumour cells in vitro in animal experiments and recently in several human safety and efficacy studies for liver, pancreas, pelvis, kidney and lung tumours.9–11 The two main factors have driven research in IRE as a treatment modality. First, studies in animals and humans have shown that connective tissue structure could be preserved with minor damage to associated blood vessels, neural tissue or other vital structures. Second, IRE lesions show a sharp demarcation between ablated and non-ablated tissue whereas lesions from thermal ablation techniques show a transitional zone containing partially damaged tissue between ablated and healthy tissue, because of partial conduction of heat or cold to the surrounding tissue.

The patients will be assigned into two groups. The first group receives a focal ablation of the prostate (one lobe using 2–3 IRE needles); the second group will have an extended ablation (one or both lobes using >3 IRE needles). This allows us to assess the end points of the study in different template scenarios. The first primary objective is to determine if the IRE ablation procedure is safe as measured by the total number of (1) device related and (2) periprocedural and postprocedural adverse events as measured using the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). The second primary objective is to determine if complete ablation of the specified targeted ablation zone is achieved as measured by histopathology assessment. The first secondary objective is to determine if procedural side effects associated with current treatments for prostate cancer are avoided as measured by the following validated questionnaires: the five-item version of the international index of erectile function (IIEF-5), international prostate symptom score (IPSS) and if required, time of indwelling catheter. The second secondary objective is to determine quality of life (QoL) and comfort measured by expanded prostate cancer index composite (EPIC) and IPSS QoL score (IPSS-QoL), postprocedural pain management and pain scores using the visual analogue scale (VAS) and length of hospital stay.12 The final secondary objective is to determine accuracy of ablation zone detection by multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) and contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS).

Methods and analysis

Trial protocol

Patients with confirmed prostate cancer scheduled for radical prostatectomy (RP) with a life expectancy of at least 10 years will consecutively undergo the IRE procedure approximately 30 days prior to the RP. The time frame is based on animal studies, which report completely dissolved IRE lesions after at least 3 weeks. Furthermore, it is in line with the Department of Health maximum allowed waiting time criteria as well as the standard time between biopsy and RP. Recruitment will take place in two academic hospitals: Academic Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands and Sismanoglio hospital, Athens, Greece. The study is approved by the research ethics committees of both hospitals and registered in the clinicaltrials.gov database (NCT01790451).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients who are scheduled for a RP and meet the inclusion criteria (box 1) will be offered to attend a screening visit. The urologist together with a research nurse will explain the study protocol and the patients’ information brochure will be provided. Patients will be excluded from the study if they meet any of the exclusion criteria listed in box 2. To rule out cardiac disorders, every patient will undergo ECG. If the patient chooses to participate, the informed consent form has to be signed accompanied by one of the research fellows.

Box 1. Inclusion criteria.

Patients with prostate cancer who are indicated to undergo a radical prostatectomy.

Life expectancy >10 years.

Able to visualise prostate gland adequately on transrectal ultrasound imaging.

No prostate calcification greater than 5 mm.

Ability of a participant to stop anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for 7 days prior and 7 days postprocedure.

Box 2. Exclusion criteria.

Bleeding disorders

Active urinary tract infection

History of bladder neck contracture

Inflammatory bowel diseases

Concurrent major debilitating illness

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD)/pacemaker/cardiac history

Prior or concurrent malignancy

Biological therapy for prostate cancer

Chemotherapy for prostate cancer

Hormonal therapy for prostate cancer within 3 months of procedure

Radiotherapy for prostate cancer

Transurethral prostatectomy or urethral stent

Prior major rectal surgery

Baseline characteristics

Physical examination will be performed and validated questionnaires (IPSS, IIEF-5 and EPIC) will be used to report baseline urinary and erectile symptoms as recommended by the International Multidisciplinary Consensus on Trial Design for Focal Therapy.13 Prostate cancer-related pain is measured on the standardised VAS, ranging from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating more severe pain.14 Postoperative pain management will be determined as well.

Imaging studies

Multiparametric MRI

mpMRI (1.5 T including diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic postcontrast MRI) will be performed pre-IRE and post-IRE, but pre-RP using an integrated pelvic phased array endorectal coil to localise the tumour and to be able to evaluate the extent of the ablation zone. The diagnostic accuracy for detecting small low-grade malignant lesions in the prostate is strongly dependent on MRI protocol, MRI quality and user experience.15 16 There are many studies in which MRI is compared with RP specimens.17–21 However, limitations in validating the MRI findings with the ‘gold standard’ whole mount histopathology arose from free hand slicing (deformation) and non-uniform distortion on fixation of the specimens. The orientation of the cutting planes in the prostatectomy specimen can be different from the scanning planes of mpMRI, and it is therefore challenging to assess the true accuracy of MRI. However, Turkbey et al provided a solution for this issue in 2010 by processing the histopathological specimens exactly according to the MRI by using a customised three-dimensional (3D) mold to slice up the RP specimen from 45 patients. The positive predictive value of 3 T mpMRI for the detection of prostate cancer increased to 98%, 98% and 100% in the overall prostate, peripheral zone and central gland, respectively.22

Contrast-enhanced ultrasound

The patients who participate in the AMC Amsterdam will undergo a CEUS pre-IRE and pre-RP to determine the completeness of the ablation zone detection by this imaging technique. CEUS involves the use of microbubble contrast agents and specialised imaging techniques to show sensitive blood flow and tissue perfusion information. CEUS is safe with no requirement for ionising radiation and no risk for nephrotoxicity and can be easily performed. Ultrasound contrast agents consist of a solution of gas-filled shell-stabilised microbubbles with a diameter in the order of micrometres. These bubbles stay inside the blood pool and travel through all blood vessels, including the microvasculature.23

Two studies have been performed with CEUS in IRE ablated lesions. In one study, CEUS was performed in patients with unresectable malignant hepatic tumours. In the second study, CEUS was performed following IRE in chemotherapy-refractory liver metastases in patients who were no candidates for surgery or radiofrequency ablation. The CEUS data showed a clearly confined devascularised lesion, corresponding to the ablated area.24 25

Clinical pathway

Patients will be admitted 1 day before the scheduled IRE procedure. The transperineal ultrasound-guided insertion of the IRE needles and the electroporation will be performed under general anaesthesia and muscle relaxants. Full paralysis during electroporation is needed to prevent patient motion due to the high-voltage pulses. The specified target area is ablated. All patients will be given a Foley catheter before the procedure as well as prophylactic antibiotics. The day following the procedure, the Foley catheter will be removed and the patient will leave the hospital after successful voiding. If this voiding is unsuccessful, the Foley catheter will be reinserted for one more week and removed at the outpatient clinic.

Adverse events and QoL assessment

The device related, periprocedural and postprocedural adverse events will be measured using the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE). CTCAE is a descriptive terminology that can be utilised for reporting adverse events. CTCAE is widely accepted throughout the oncology community as the standard classification and severity grading scale for adverse events in cancer therapy clinical trials and other oncology settings.

A grading scale is provided for each adverse event term.26 QoL will be assessed by a validated comprehensive instrument (EPIC) designed to evaluate patient functioning and symptoms after prostate cancer treatment. The IPSS urinary QoL score (0–5) will be used for with low scores demonstrating good QoL.

Follow-up

Patients will be dismissed 1 day after the procedure, once prostate-specific antigen (PSA) measurement, adverse event reporting and VAS scoring have been completed and when the clinical condition allows it. At 1 and 4 weeks post-IRE, the patients are physically examined. Uroflowmetry is obtained and the patient is asked to fill out each questionnaire again. Two weeks post-IRE, a consultation is scheduled over the telephone. At one, two and 4 weeks post-IRE all symptoms and adverse events will be recorded. Biostatisticians of the CROES will complete all data analysis. In case of clear harm to the participants, defined as severe adverse events (grade 3; CTCAE V.4.0) or futility of the study, the trial will be terminated in consultation with independent interdepartmental monitors and the data safety monitoring board. An overview of participants’ timeline is added in online supplementary appendix 1.

The histological examination of the prostate specimen from both participating centres will be performed at the department of pathology in the AMC, Amsterdam. It has been hypothesised that the IRE ablation zone can be defined by using the 2D ultrasound images in combination with the planning software on the IRE device. Histological examination will include macroscopic inspection—overall appearance, size and weight. Serial whole mount sections of 3–5 mm, perpendicular to the urethra, are followed by a cut surface of each slice and inspected macroscopically and documented by photography. Whole mount slices from apex to base will be embedded in paraffin; 4 µm thick sections will be cut and examined with H&E staining. The boundaries of the ablation zone will be determined by light microscopy and marked on the slides, using the ultrasound imaging as a template. The volume of tissue alteration will be determined by adding the areas, as calculated using planimetrical analysis in AMIRA software (FEI Visualization Sciences Group). The outcome of the histopathological examination will be communicated to the patient at 1 or 2 weeks in follow-up.

The mpMRIs will be evaluated by an uroradiologist. The ablation zones will be precisely demarcated and 3D reconstructed using AMIRA software. Subsequently, histopathology imaging has to be assessed to determine the accurateness of ablation zone detection by mpMRI and CEUS and in order to design a valid preplanning model for IRE in prostate cancer.

Sample size and data analysis plan

The sample size of 16 patients is based on comparable studies with similar study design. Beerlage et al27 performed a phase II study with high-intensity focused ultrasound with a sample size of 20 followed by a published case series of 14 patients. The other studies using radiofrequency (n=14), transurethral ultrasound therapy (n=8) and cryotherapy (n=7) reported similar patient numbers.28–30

Brausi et al was among the first presenting results of an IRE pilot safety study in 11 patients with low-risk prostate cancer. No major complications occurred during the procedure. The hospital stay was 1 day for all patients. Follow-up was done at 14, 30, 90 and 180 days and 19 months with physical examination, PSA, IPSS and IIEF. The mean IPSS reduced from 9.5 to 7.7, 7, 6.1, 4.28 and 4, respectively, and the mean IIEF went from 16.2 to 13.2, 10.5, 10.5, 11 and 17.3. During follow-up, one patient presented with an acute urinary retention and three had transient urge incontinence. Mean PSA was 3.5, 2.9, 3.3 and 3.12 ng/mL after 30, 90, 180 days and 19 months, respectively. Prostate biopsies of the ablated area were performed after 1 month with a mean of 25 (range 15–41) biopsies. Pathological report was negative in 8 of the 11 patients (73%) and showed coagulative necrosis, granulomatosis, fibrosis and haemosiderosis. Three patients had a persistent adenocarcinoma. Therefore, one patient underwent RP and two were retreated with IRE.31

Patients will be assigned with a research code on consecutive order as they enter the study. During the study, no information that can be related to the patient is shown on study material.

Outcomes

The primary outcome is safety as measured by the composite of procedural device and postprocedural adverse events, measured with CTCAE, EPIC-score, IPSS or required catheterisation time and IIEF and efficacy of ablation determined by histological examination postprostatectomy. Secondary outcomes will be patients’ procedure satisfaction measured by patient satisfaction questions (included in EPIC score), postprocedural pain management and VAS pain score, time to ambulation, length of hospital stay.

Device and procedure

The AngioDynamics Inc HVP-01 Electroporation System (also registered as the NanoKnife IRE System, figure 1) consists of three components: a Low Energy Direct Current generator, needle electrodes and Accusync ECG trigger (Accusync, Milford, Connecticut, USA).

Figure 1.

Low Energy Direct Current Electroporation System (NanoKnife IRE System, AngioDynamics).

The trigger was used to supply the pulses at a cardiac autosynchronous rate to decrease the risk of cardiac arrhythmias. The procedure will be performed under general anaesthetic and full paralysis using rocuronium (dose 1 mg/kg) as well as a saddle block. The patients are placed in the extended lithotomy position and sterile draped and a transurethral catheter (16 Ch) is inserted (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Patient placed in extended lithotomy position with transperineally inserted electrodes using brachytherapy grid under ultrasound guidance.

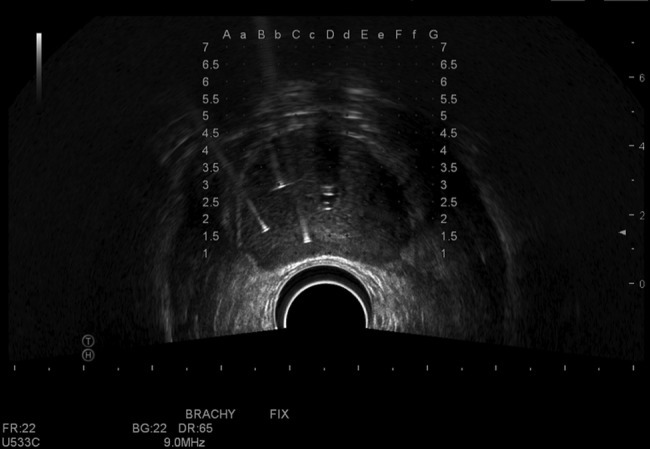

The surgeon will assign the patients to two parallel groups. One group will have a focal ablation of the prostate; the other group will receive an extended ablation. In this way, we are able to assess the side effects of electroporation with different treatment scenarios. In grouping the patients, the tumour position will be taken into account monitored by preceding biopsies, MRI and CEUS. Therefore, mainly the tumour will be treated but also a part of surrounding healthy prostate tissue. The effects and the safety of the technique on both the tissues will be observed. To define the treatment area, a biplane transrectal ultrasound system (Amsterdam Hi Vision Preirus, Hitachi Medical Systems, The Netherlands, equipped with an endocavity probe, type EUP-U533, C8.0–4.0, L10.0-5.0; Athens 2102 Falcon and 2202Pro Focus, BK Medical, Denmark, equipped with an endocavity probe models 8658 and 8848) will be used to visualise the prostate in sagittal and axial direction. The volume and shape of the prostate will be determined. These data will be entered into the planning software system. The specified area will be chosen for ablation. Two up to six 19-gauge unipolar electrode needles will be inserted transperineally using a brachytherapy grid under continuous ultrasound guidance (figures 3 and 4).

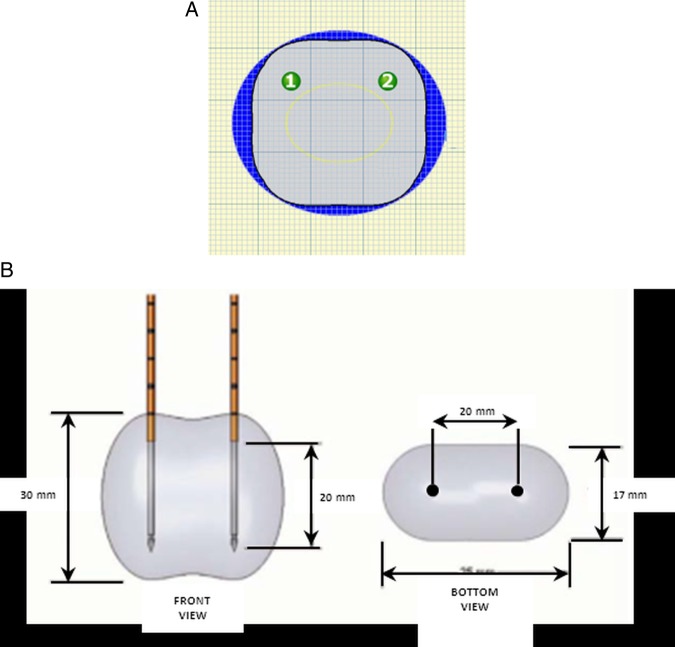

Figure 3.

Three electrodes transperineally inserted through a brachytherapy grid.

Figure 4.

Transrectal ultrasound image with three inserted electrodes in right prostate lobe.

For an extended ablation with >4 electrodes, 2 electrodes will be repositioned followed by a second IRE course including the 4 electrodes in place. The locations will be verified using sagittal and axial ultrasound images of the prostate. Minimal distances between the needles and between the needles and essential structures (urethra, bladder neck, capsule and rectum) will be measured by ultrasound. The data will be transferred to the build-in planning software of the NanoKnife IRE device (figure 5).

Figure 5.

Planning software with localisation of two needles (green numbered circles).

The ablation procedure uses 90 pulses of 90 μs duration each with an electric field of 1500 V/cm between an electrode pair. Electric pulses are delivered between each of the electrode pairs. The actual treatment time will be approximately 5–10 min whereas the whole procedure is scheduled for 60 min.

Ethics and dissemination

Data will be presented at international conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals. The study is conducted and funded by the Clinical Research Office of the Endourological Society (CROES). The CROES is an official organ within the Endourological Society responsible for organising, structuring and favouring a global network on endourological research. This research received no other specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Benefits and harms

There are no benefits for the patients that participate in this study. Patients need to be informed about the risks of surgery and the procedure. Because the IRE technology is relatively new, there may be potential risks and side effects that are unknown at this time. A clinical risk analysis has been prepared which describes the hazards associated with the use of the device and the associated clinical risks associated with the procedure (eg, general anaesthesia) along with the mitigations available to reduce this hazard. Potential risks associated with the use of IRE include, but are not limited to the list in online supplementary appendix 2.

Other accepted focal treatments for prostate cancer, such as percutaneous prostate cryoablation, have limitations such as variable damage at the lesion margins, injury to adjacent structures such as the rectum, urethra and neurovascular bundle, and long procedure times. These characteristics have limited the widespread acceptance of this modality despite certain demonstrated advantages over the more traditional treatments of radiation and RP. Research has been shown to have significant advantages in ablating hepatic tissue, such as rapid lesion creation, rapid lesion resolution, sparing of structures such as vessels and bile ducts, and uniform destruction throughout the IRE lesion.11 It is theorised that these advantages will also apply to use in the prostate.

Data and Safety Monitoring Board

The Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) will act in an independent, expert and advisory capacity to monitor participant safety, and evaluate the efficacy and the overall conduct of the study. The responsibilities of the DSMB are to monitor safety data on a regular basis and, if required, on ad hoc basis to guide recommendation for continuation of the study or early termination because of clear harm. Furthermore to monitor efficacy data on a regular basis to guide recommendations for continuation of the study or early termination because of clear harm or futility, and to evaluate the overall conduct of the trial, including (1) monitoring of compliance with the protocol by participants and investigators; (2) monitoring of recruitment figures and losses to follow-up; (3) monitoring planned sample size assumptions; (4) reports on data quality; (5) reports on completeness of data and (6) monitoring of continuing appropriateness of patient information. The charter is included in online supplementary appendix 3.

Compensation for injury

The investigator has a liability insurance that is in accordance with article 7, subsection 6 of the WMO. This insurance is in accordance with the legal requirements in the Netherlands (Article 7 WMO and the Measure regarding Compulsory Insurance for Clinical Research in Humans of 23 June 2003). This insurance provides cover for damage to research participants through injury or death caused by the study (€450 000 for death or injury for each participant who participates in the research; €3 500 000 for death or injury for all paticipants who participate in the research; €5 000 000 for the total damage incurred by the organisation for all damage disclosed by scientific research for the investigator in the meaning of said Act in each year of insurance coverage).

Discussion

This will be the largest study cohort on IRE pre-RP. Previously, Neal et al described two human IRE cases performed without serious adverse events followed by uncomplicated radical prostatectomies. The histology shows tissue necrosis plus a variable extent of reactive stromal fibrosis, inflammatory infiltrates and regenerative changes in epithelial lining of prostatic ducts.32 So far, several focal therapies have been proposed and investigated for prostate cancer. In the past, the first phase I/II assessments of new focal ablation modalities have often been skipped and these methods were immediately used in clinical practice. The primary goals of this project are to determine the safety and efficacy of IRE. The interest in QoL is increasingly important, and it is therefore of paramount importance to assess this aspect in addition to adverse events, pain and side effects. Furthermore, it is essential to select validated and recommended questionnaires, to be able to compare the focal therapy trial outcomes.13 An additional aspect of this study is the short-term evaluation of ‘salvage RP’, which is important, because some patients will fail focal therapy and will need secondary radical resection of the prostate.

This study protocol has some limitations. First, ablations of the posterior peripheral zone directly adjacent to the rectum have to be avoided in order to minimise possible rectal damage. Hydrodissection of the Denonvilliers’ space may be an option to be able to ablate closer to the capsule of this zone in case of later projects evaluating the role of IRE as focal treatment.

Second, the maximum period between IRE and RP in this trial is 4 weeks. This limits analysis of the histopathology beyond this timeframe. It is clear that postponing the RP for evolving IRE effects is ethically not feasible. We will not use a customised mpMRI-based 3D-printed prostatectomy mold as described by Turkbey et al.22 Consequently, MRI slices and histopathology slides will not precisely match which will impede the exact comparison, resulting in a reduction of the correlation.

Conclusion

This trial will investigate the safety and efficacy of IRE in prostate cancer. Safety will be evaluated by reporting adverse events; side effects and QoL using validated questionnaires. Histopathology and radiological imaging will assess efficacy. The outcomes of this study will be used to develop a multicentre single-blind randomised clinical trial (NCT01835977).

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: WvdB, DMdB and BGM conceived the trial concept and designed the protocol. IMV, AAK, PJZ, MPLP, DPV, CDSH, MRWE, HW and TMdR helped develop the trial design and protocol. JJMCHdlR is the principal investigator and takes overall responsibility for all aspects of trial design, the protocol and trial conduct. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: JJMCHdlR is paid consultant to AngioDynamics.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committe of Academic Medical Center Amsterdam and Athens Medical University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Onik G, Mikus P, Rubinsky B. Irreversible electroporation: implications for prostate ablation. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2007;6:295–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li W, Fan Q, Ji Z, et al. The effects of irreversible electroporation (IRE) on nerves. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e18831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsivian M, Polascik TJ. Bilateral focal ablation of prostate tissue using low-energy direct current (LEDC): a preclinical canine study. BJU Int 2013;112:526–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davalos RV, Mir LM, Rubinsky B. Tissue ablation with irreversible electroporation. Ann Biomed Eng 2005;33:223–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thomson KR, Cheung W, Ellis SJ, et al. Investigation of the safety of irreversible electroporation in humans. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:611–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubinsky B. Irreversible electroporation in medicine. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2007;6:255–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang DC, Reese TS. Changes in membrane structure induced by electroporation as revealed by rapid-freezing electron microscopy. Biophys J 1990;58:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maor E, Ivorra A, Leor J, et al. The effect of irreversible electroporation on blood vessels. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2007;6:307–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ball C, Thomson KR, Kavnoudias H. Irreversible electroporation: a new challenge in “out of operating theater” anesthesia. Anesth Analg 2010;110:1305–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garner AL, Cheng G, Cheng N, et al. Ultrashort electric pulse induced changes in cellular dielectric properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007;362:139–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scheffer HJ, Nielsen K, de Jong MC, et al. Irreversible electroporation for nonthermal tumor ablation in the clinical setting: a systematic review of safety and efficacy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2014;25:997–1011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wei J, Dunn R, Litwin M, et al. Development and validation of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology 2000;56:899–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Bos W, Muller BG, Ahmed H, et al. Focal therapy in prostate cancer: international multidisciplinary consensus on trial design. Eur Urol 2014;65:1078–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huskisson EC. Measurement of pain. Lancet 1974;2:1127–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mullerad M, Hricak H, Wang L, et al. Prostate cancer: detection of extracapsular extension by genitourinary and general body radiologists at MR imaging. Radiology 2004;232:140–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barentsz JO, Richenberg J, Clements R, et al. ESUR prostate MR guidelines 2012. Eur Radiol 2012;22:746–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miao H, Fukatsu H, Ishigak T. Prostate cancer detection with 3-T MRI: comparison of diffusion-weighted and T2-weighted imaging. Eur J Radiol 2007;61:297–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Hricak H, Shukla-Dave A, et al. Clinical stage T1c prostate cancer: evaluation with endorectal MR imaging and MR spectroscopic imaging. Radiology 2009;253:425–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turkbey B, Pinto PA, Mani H, et al. Prostate cancer: value of multiparametric MR imaging at 3T for detection—histopathologic correlation. Radiology 2010;255:89–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riches SF, Payne GS, Morgan VA, et al. MRI in the detection of prostate cancer: combined apparent diffusion coefficient, metabolite ratio, and vascular parameters. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:1583–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitajima K, Kaji Y, Fukabori Y, et al. Prostate cancer detection with 3T MRI: comparison of diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in combination with T2-weighted imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010;31:625–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turkbey B, Mani H, Shah V, et al. Multiparametric 3T prostate magnetic resonance imaging to detect cancer: histopathological correlation using prostatectomy specimens processed in customized magnetic resonance imaging based molds. J Urol 2011;186:1818–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smeenge M, Mischi M, Laguna Pes MP, et al. Novel contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging in prostate cancer. World J Uro l2011;29:581–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasivisvanathan V, Thapar A, Oskrochi Y, et al. Irreversible electroporation for focal ablation at the porta hepatis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2012;35:1531–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wiggermann P, Zeman F, Niessen C, et al. Percutaneous irreversible electroporation (IRE) of hepatic malignant tumours: contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) findings. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2012;52:417–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.The National Cancer Institute issued the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4.0 on 29 May 2009. http://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5×11.pdf

- 27.Beerlage HP, van Leenders GJLH, Oosterhof GON, et al. High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound (HIFU) followed after one to two weeks by radical retropubic prostatectomy: Results of a prospective study. Prostate 1999;39:41–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zlotta AR, Djavan B, Matos C, et al. Percutaneous transperineal radiofrequency ablation of prostate tumour: safety, feasibility and pathological effects on human prostate cancer. Br J Urol 1998;81:265–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chopra R, Colquhoun A, Burtnyk M, et al. MR imaging-controlled transurethral ultrasound therapy for conformal treatment of prostate tissue: initial feasibility in humans. Radiology 2012;265:303–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pisters LL, Dinney CP, Pettaway CA, et al. A feasibility study of cryotherapy followed by radical prostatectomy for locally advanced prostate cancer. J Urol 1999;161:509–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brausi MA, Giliberto GL, Simonini GL, et al. Irreversible electroporation (IRE), a novel technique for focal ablation of prostate cancer (PCa): results of a interim pilot safety study in low risk patients with Pca. Presented at EAU. Vienna, March 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neal RE, Milar JL, Kavnoudias H, et al. In vivo characterization and numerical simulation of prostate properties for non-thermal irreversible electroporation ablation. Prostate 2014;74:458–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.