Abstract

Plasma glucose, insulin, and C-peptide responses during an OGTT are informative for both research and clinical practice in type 2 diabetes. The aim of this study was to use such information to determine insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion so as to calculate an oral glucose disposition index (DIOGTT) that is a measure of pancreatic β-cell insulin secretory compensation for changing insulin sensitivity. We conducted an observational study of n = 187 subjects, representing the entire glucose tolerance continuum from normal glucose tolerance to type 2 diabetes. OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity (SI OGTT) was calculated using a novel multiple-regression model derived from insulin sensitivity measured by hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp as the independent variable. We also validated the novel SI OGTT in n = 40 subjects from an independent data set. Plasma C-peptide responses during OGTT were used to determine oral glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSISOGTT), and DIOGTT was calculated as the product of SI OGTT and GSISOGTT. Our novel SI OGTT showed high agreement with clamp-derived insulin sensitivity (typical error = +3.6%; r = 0.69, P < 0.0001) and that insulin sensitivity was lowest in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. GSISOGTT demonstrated a significant inverse relationship with SI OGTT. GSISOGTT was lowest in normal glucose-tolerant subjects and greatest in those with impaired glucose tolerance. DIOGTT was sequentially lower with advancing glucose intolerance. We hereby derive and validate a novel OGTT-derived measurement of insulin sensitivity across the entire glucose tolerance continuum and demonstrate that β-cell compensation for changing insulin sensitivity can be readily calculated from clinical variables collected during OGTT.

Keywords: β-cell function, insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, disposition index, oral glucose tolerance, hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, type 2 diabetes, obesity, insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, insulin sensitivity index

type 2 diabetes is characterized by chronic hyperglycemia that develops when insulin secretion fails to compensate for impaired peripheral tissue insulin sensitivity (SI) (4). Determining insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion is critical for understanding the mechanisms related to the risk of developing type 2 diabetes. Gold standard measurements of insulin sensitivity are obtained from hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp methodology (1); however, this technique is logistically demanding and is typically confined to the research setting. The oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT), which is used clinically to determine glucose tolerance, can be used to derive estimates of insulin sensitivity as a feasible alternative to clamp methodology. The most widely used estimate, the Matsuda index (8), is a function of plasma glucose and insulin during OGTT. The index was correlated with gold standard clamp methodology in 153 subjects with varying glucose tolerance (8) but provides unitless arbitrary values, and therefore, the true agreement with an actual measure of insulin sensitivity cannot be determined. Furthermore, with increasing glucose intolerance the Matsuda index showed poorer correlation with clamp-derived measurements (8), which was likely due to a diminishing relationship between plasma glucose and insulin levels with increasing glucose intolerance. Following this, Stumvoll et al. (15) developed a multiple regression-derived measurement of insulin sensitivity (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) in n = 104 nondiabetic subjects that showed excellent agreement with clamp-derived insulin sensitivity (r = 0.77 and 0.79 in normal and impaired glucose tolerant subjects). This index is very useful, as it provides a quantifiable value of insulin-stimulated glucose disposal; however, it has not been validated in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Because insulin sensitivity is vastly impaired in subjects with type 2 diabetes, it is of great value to research and clinical practice that an OGTT index is also validated in this population.

Pancreatic β-cell secretory function [i.e., glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS)] can be readily determined during an OGTT by measuring insulin secretory responses. Glucose disposal during an OGTT is determined largely by β-cell function and the underlying level of insulin-stimulated glucose metabolism (insulin sensitivity). Because of the inverse relationship between β-cell function and insulin sensitivity, a glucose disposition index, which is a measure of pancreatic β-cell compensation for changing insulin sensitivity, can be determined as the product of GSIS and insulin sensitivity. Originally, this was verified using insulin sensitivity and the acute insulin response to glucose measured during intravenous glucose tolerance testing (5). However, as demonstrated by Meier et al. (9), peripheral blood insulin is a poor marker of prehepatic insulin levels because, although insulin and C-peptide are secreted in equimolar amounts, 40–80% of insulin is extracted by the liver at first pass. As such, peripheral blood C-peptide levels provide a better estimate of prehepatic insulin levels, and so using C-peptide to estimate the insulin secretion component of the disposition index will provide a more accurate physiological assessment.

In this study, we used a large sample (n = 187) that is representative of the entire glucose tolerance continuum to develop a novel OGTT-derived measurement of insulin sensitivity (SI OGTT) and calculated a simple glucose disposition index (DIOGTT; a measurement of β-cell compensation for changing insulin sensitivity). We validated these novel indices using an independent data set of n = 40 subjects that were also representative of the entire glucose tolerance continuum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects.

This study was performed at two locations: the clinical research laboratories at the Centre of Inflammation and Metabolism, Rigshospitalet, Denmark, and the Clinical Research Unit at the Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH. Data were collected between January 2000 and December 2012. Potential participants in the local municipal areas responded to newspaper/radio advertisements and underwent medical screening to determine eligibility for the study. Evidence of prior or current chronic pulmonary, hepatic, renal, gastrointestinal, or hematological disease, weight loss (>2 kg in the last 6 mo), and smoking were the exclusion criteria. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committees at both institutions. After full explanation of the purpose, nature, and risk of all procedures used, subjects provided informed consent prior to participation. Data from some subjects participating in this study has been published previously for other purposes (6, 7, 12, 13). The primary outcomes of the study were derived from a cohort that included n = 187 subjects, for whom subject characteristics are shown in Table 1. As described below, a validation cohort of an additional n = 40 subjects was also studied.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics

| NGT | IGT | T2DM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (M/F) | 92 (69/23) | 43 (24/19) | 52 (26/26) |

| Age, yr | 50 ± 2 | 61 ± 1*** | 59 ± 1*** |

| Body weight, kg | 81.7 ± 1.7 | 95.7 ± 2.4*** | 89.6 ± 2.0* |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 26.4 ± 0.5 | 32.8 ± 0.8*** | 31.0 ± 0.7* |

| Whole-body adiposity, % | 28.0 ± 1.2 | 37.8 ± 1.5*** | 37.4 ± 1.3*** |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 131 ± 2 | 137 ± 3 | 139 ± 2* |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 79 ± 1 | 82 ± 2 | 85 ± 1** |

| Fasting plasma total cholesterol, mM | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.1 |

| Fasting plasma triglycerides, mM | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.3 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mM | 5.2 ± 0.1 | 5.7 ± 0.1* | 7.4 ± 0.3***,# |

| 2-hour OGTT plasma glucose, mM | 6.0 ± 0.1 | 9.2 ± 0.1*** | 14.8 ± 0.4***,# |

| Hemoglobin A1c, % | 5.6 ± 0.1 | 5.8 ± 0.1 | 6.5 ± 0.1***,# |

| Hemoglobin A1c, mmol/mol | 37.7 ± 0.9 | 39.7 ± 0.6 | 47.8 ± 0.9***,# |

Data are means ± SE; characteristics of subjects (n =187) representing the glucose tolerance continuum are shown. NGT, normal glucose tolerance; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; M, males; F, females; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used to examine group differences.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.001 vs. NGT;

P < 0.001 vs. IGT.

Pretest control period.

Subjects being treated with antidiabetic drugs (metformin, n = 17; sulfonylureas, n = 6; glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs, n = 3; dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors, n = 2) withheld from their medication for 5 days prior to metabolic testing, during which time dietary intake and physical activity were recorded in an outpatient setting. Subjects also abstained from structured exercise for ≥24 h prior to metabolic testing.

Clinical measurements.

Height and weight were measured using standard techniques. Whole body adiposity was estimated using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar iDXA; GE Healthcare, Madison, WI). On a separate day, following an 8- to 10-h overnight fast, insulin sensitivity was determined using a 2-h 40 mU·m2·min−1 hyperinsulinemic euglycemic (5 mmol/l) clamp (n = 187). Subjects came to the laboratory and had two intravenous lines placed: an anteriograde catheter in an antecubital vein and a retrograde catheter in a dorsal hand vein on the contralateral arm. The hand was warmed with a heating blanket to arterialize venous blood. Baseline blood samples were taken, and a primed (20 μmol·kg−1·fasting glucose−1: 5 mmol/l), continuous 0.2 μmol·kg−1·min−1 infusion of [6,6-2H2]glucose was begun to measure endogenous glucose production. After 2-h, a primed, continuous 40 mU·m2·min−1 infusion of insulin began. The priming dose of insulin was progressive over the first 10 min: 125, 54, 49, 47, 43, and 40 mU·m2·min−1, changing every 2 min. After 5 min, a variable rate of 20% glucose infusion began (starting at an arbitrary value of 22.2 μmol·kg−1·min−1) so as to “clamp” plasma glucose concentrations at 5 mmol/l for the duration of the clamp. The 20% glucose was spiked with [6,6-2H2]glucose to 3% enrichment. The separate infusion of [6,6-2H2]glucose was ceased after 30 min. Alterations to the 20% glucose infusion rate were made every 5 min according to a computational algorithm based on the calculations of DeFronzo et al. (1), which was in line with measured arterialized plasma glucose concentrations. The clamp was stopped after 2 h. Additional plasma samples were collected 10 min apart during the final 30 min of the clamp for the measurement of glucose tracer enrichment and serum insulin. Glucose kinetics were determined using a single-pool, steady-state model of glucose kinetics (Ra = Rd = tracer infusion rate/plasma glucose enrichment) (14). During the final 30 min of the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, the mean rate of glucose disappearance was divided by the mean plasma insulin concentration to determine insulin sensitivity (SI Clamp; μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1). On a separate day, standard 2-h, 75-g OGTTs were also performed (n = 187). Following an 8- to 10-h overnight fast, subjects came to the laboratory and had an anteriograde catheter placed in an antecubital vein. Baseline blood samples were taken, and subjects were instructed to ingest a 75-g bolus of glucose dissolved in 300 ml of water within a 5-min period. Further venous blood samples were collected during the OGTT to measure plasma glucose and serum insulin and C-peptide concentrations.

Insulin sensitivity during OGTT.

Previously published OGTT-derived indices of insulin sensitivity (SI OGTT) were calculated (8, 15). SI OGTT Matsuda (arbitrary units) = 10,000/√(FG × FI × MG × MI), where F = fasting, M = mean (over 120 min), G = glucose (mg/dl), and I = insulin (μU/ml) (8). SI OGTT Stumvoll (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) = 0.226 − 0.0032 × BMI − 0.0000645 × I120 − 0.0037 × G90, where I120 = insulin (pmol/l) at t = 120 min and G90 = glucose (mmol/l) at t = 90 min (15). Furthermore, using hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp-derived measures of insulin sensitivity (SI Clamp; μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) as the independent variable and demographics [age, sex, weight, BMI, %body fat, physical fitness (V̇o2max)], systolic and diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, triglycerides, glycosylated hemoglobin (Hb A1c), and measurements of plasma glucose (mM) and serum insulin (pM) during OGTT as dependent measurements, we used forward stepwise multiple regression to develop a modification to the Stumvoll insulin sensitivity index (SI OGTT) in n = 187 subjects, representing the whole glucose tolerance continuum.

Insulin secretion during OGTT.

Early-phase GSIS was calculated as incremental C-peptide from 0 to 30 min (pM) and the area under the C-peptide curve (AUC; pM/min) from 0 to 30 min. Late-phase GSIS was calculated as AUC C-peptide (pM/min) from 30 to 120 min. These GSIS measurements were additionally quantified per unit of plasma glucose. Full C-peptide data were measured in n = 171 subjects.

Oral glucose disposition.

Early- and late-phase DI was calculated as the product of SI OGTT and GSISOGTT, using plasma C-peptide responses to OGTT as the marker of prehepatic insulin levels. To validate this, we tested for an inverse linear relationship between log10(GSISOGTT) and log10(SI OGTT) in n = 157 subjects.

Blood sampling and analysis.

Venous blood was collected into tubes containing NaF for glucose measurement or into plain tubes containing no anticoagulant for insulin and C-peptide measurement (Vacuette; Greiner Bio-One). Plain tubes were allowed to clot for 30 min at room temperature, whereas NaF tubes were kept on ice. Blood was centrifuged at 2,000 g for 15 min at room temperature, and respective serum/plasma was stored at −80°C until analysis. Plasma glucose concentrations were measured using a bedside analyzer (YSI Stat; Yellow Springs Instruments), serum insulin and C-peptide concentrations were determined by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (E-modular; Roche, Switzerland), and plasma total cholesterol and triglycerides were determined by colorimetric assays (P-modular; Roche). To ensure standardization of subject recruitment and sample collection/storage/analysis during the time course of the study, all of the above-described protocols followed those used in the laboratory of coauthor J. P. Kirwan.

Validation data set.

An independent data set collected at the Centre for Inflammation and Metabolism between September 25, 2009, and October 6, 2010 (by coauthor M. Pedersen) was used to validate our newly developed SI OGTT. This included n = 40 subjects (27 male, 13 female), age 55 ± 1 yr, BMI 29.1 ± 0.8 kg/m2. Of these subjects, n = 13 were normal glucose tolerant (NGT), n = 12 were impaired glucose tolerant (IGT), and n = 15 had type 2 diabetes (T2DM), according to their 2-h plasma glucose measured during OGTT. All subjects underwent the same procedures as above. The methods were identical except for a minor difference in the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp methodology, where insulin (Actrapid; Novo Nordisk, Bagsværd, Denmark) was infused intravenously for 240 min at a constant rate of 120 mU·m2·min−1 and plasma glucose measured at 5-min intervals from t = 0 to 60 min and at 10-min intervals from t = 60 to 240 min. Plasma glucose concentrations were clamped at 5.0 ± 0.2 mmol/l by adjusting the infusion rates of 20% (wt/vol) glucose using a computer-controlled infusion pump. In this validation data set, subject recruitment and sample collection and storage were conducted in a manner similar to the model development data set above; however, it is important to note that sample analysis took place in a different laboratory, and glucose analysis was performed on a different platform (ABL; Radiometer).

Statistics.

Bland-Altman analysis was used to determine the agreement between SI OGTT (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) and the gold standard SI Clamp (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1). Typical errors of measurement were then calculated as the standard error of the differences between the SI OGTT and SI Clamp for all subjects. Linear regression was used to examine relationships between variables. One-way ANOVA and Bonferroni post hoc tests were used to assess differences between glucose tolerance groups. These analyses were conducted using Prism version 6 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). To derive a regression equation to calculate SI OGTT, forward stepwise multiple regression was conducted. SI Clamp (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) was used as the independent variable, and several input variables (described above) that we considered to be associated with insulin sensitivity were used as dependent variables. This analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20 (IBM). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Insulin sensitivity.

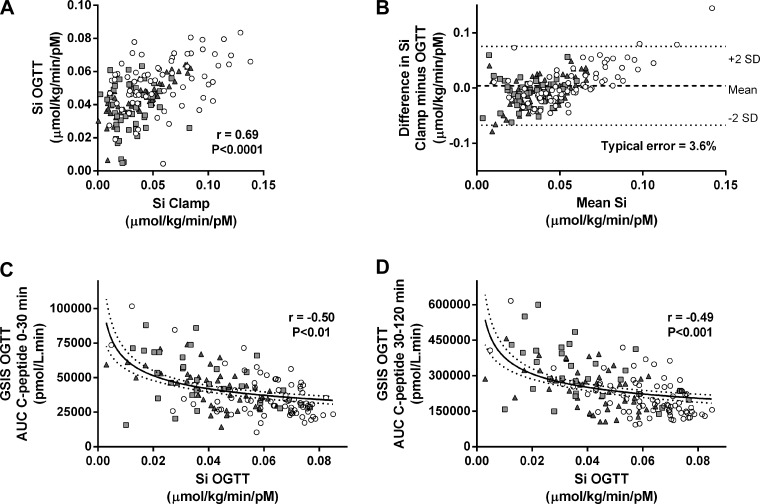

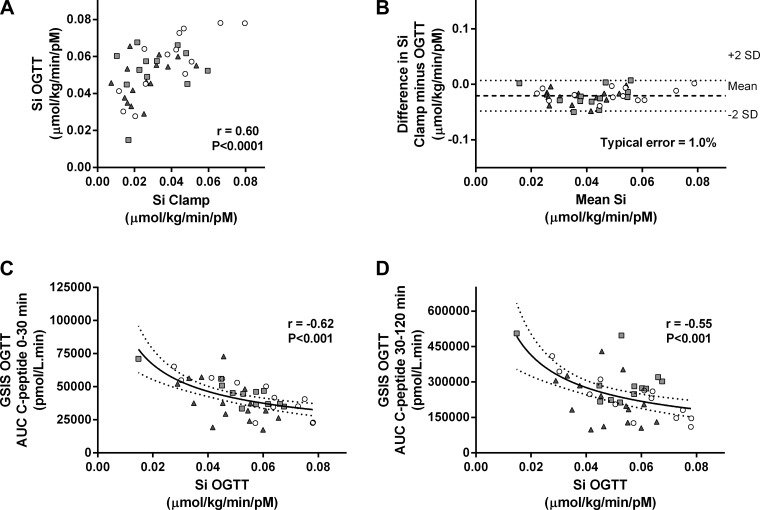

Multiple regression analyses revealed that only BMI, plasma glucose measured at 120 min during OGTT (G120; mM), and insulin measured 30 (I30; pM) and 90 min (I90) into OGTT were significant predictors of clamp-derived insulin sensitivity. As a result, we used SI OGTT (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) = 0.138 − (0.00231 × BMI) − (0.00118 × G120) − (0.0000135 × I30) − (0.00000678 × I90) to calculate insulin sensitivity and validated this novel measurement against the hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (Fig. 1A). Standard errors of the coefficients were as follows: constant (±0.0122, P < 0.0001), BMI (±3.61 × 10−4, P < 0.0001), G120 (±3.66 × 10−4, P < 0.01), I30 (±5.46 × 10−6, P < 0.01), and I90 (±3.56 × 10−6, P < 0.05); the typical error of measurement for the new index was 3.4% (range 18.1 to −6.3%; Fig. 1B). Typical error cannot be calculated for the SI OGTT Matsuda because it has arbitrary units, and therefore, agreement with SI Clamp cannot be determined. Table 2 shows correlation coefficients for the comparison of OGTT-derived indices of insulin sensitivity with gold standard euglycemic clamp-derived measurements of insulin sensitivity. The new SI OGTT index significantly correlated with gold standard SI Clamp in all subgroups across the glucose tolerance continuum. We also validated our new SI OGTT index against insulin sensitivity measured during a clamp using data collected in an independent study. SI OGTT and SI Clamp were significantly correlated (Fig. 2A) in this validation data set, and the values from these two methods showed good agreement (Fig. 2B). Following development and validation of the model, we compared SI OGTT between groups. Table 3 and Fig. 3A indicate that insulin sensitivity was significantly lower in impaired glucose-tolerant and type 2 diabetic subjects compared with normal glucose-tolerant subjects but was not different between the impaired glucose-tolerant and type 2 diabetic groups.

Fig. 1.

Development of novel oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT)-derived estimates of insulin sensitivity (SI) and β-cell compensatory function. SI Clamp (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) was measured during 2-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamps in subjects representative of a heterogeneous population with respect to age, BMI, adiposity, and glucose tolerance status [○, normal glucose tolerant (NGT); gray squares, impaired glucose tolerant (IGT); gray triangles, type 2 diabetic (T2DM)]. Insulin sensitivity was also estimated during OGTT (SI OGTT, μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) in the same subjects by multiple regression. A: SI Clamp and SI OGTT were significantly correlated (n = 187). B: Bland-Altman analysis of the mean difference between SI Clamp and SI OGTT measurements (dashed line) ± 2 standard deviations (dotted lines) indicated good agreement between the measurements (n = 187; typical error = +3.6%). Early- [area under the C-peptide curve (AUC) 0–30 min] and late-phase (AUC C-peptide 30–120 min) glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) were measured during OGTT. To determine whether GSISOGTT was inversely related to SI OGTT, nonlinear (log-log) regression was performed (n = 157). C and D: significant inverse correlations (solid line) were found between SI OGTT and early-phase GSISOGTT [r = −0.50, P = 0.009; log(GSISOGTT) = −0.295 × log(SI OGTT) + 4.21; C] and between SI OGTT and late-phase GSISOGTT [r = −0.49, P = 0.002; log(GSISOGTT) = −0.294 × log(SI OGTT) + 4.99; D]. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 2.

Comparison of OGTT-derived insulin sensitivity with clamp-derived measurements

| SI Clamp Vs.: | NGT | IGT | T2DM | All Subjects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model development data set | ||||

| SI OGTT Matsuda | 0.59*** | 0.45** | 0.38* | 0.46*** |

| SI OGTT Stumvoll | 0.83*** | 0.48** | 0.38** | 0.58*** |

| SI OGTT Solomon | 0.79*** | 0.54** | 0.46*** | 0.69*** |

| Independent validation data set | ||||

| SI OGTT Matsuda | 0.66*** | 0.41** | 0.41** | 0.46*** |

| SI OGTT Stumvoll | 0.75*** | 0.51** | 0.45** | 0.54*** |

| SI OGTT Solomon | 0.81*** | 0.55** | 0.49** | 0.61*** |

Data indicate Pearson's product-moment correlation coefficients (r values) for comparisons between variables. SI, insulin sensitivity. Comparisons were made between SI measured during the gold standard hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (SI Clamp) and SI estimated during OGTT (SI OGTT). Comparison data are shown for both the model development data set and the independent validation data set. Statistical significance of the relationships is represented by

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.001.

Fig. 2.

Validation of OGTT-derived estimates of insulin sensitivity and β-cell compensatory function. In a data set that was collected independently by coauthor M. Pedersen, SI Clamp (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) was measured during 4-h hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp in n = 40 subjects representative of the entire glucose tolerance continuum (○, NGT; gray squares, IGT; gray triangles, T2DM). Insulin sensitivity was also calculated using our novel SI OGTT (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1). A: SI Clamp and SI OGTT were significantly correlated (n = 40). B: Bland-Altman analysis of the mean difference between SI Clamp and SI OGTT measurements (dashed line) ± 2 standard deviations (dotted lines) indicated good agreement between the measurements (n = 40; typical error = −1.0%). To determine whether GSISOGTT was inversely related to SI OGTT, nonlinear (log-log) regression was performed (n = 40). C and D: significant inverse correlations (solid line) were found between SI OGTT and early-phase GSISOGTT [r = −0.62, P < 0.001; log(GSISOGTT) = −0.525 × log(SI OGTT) + 3.93; C] and between SI OGTT and late-phase GSISOGTT [r = −0.55, P < 0.001; log(GSISOGTT) = −0.583 × log(SI OGTT) + 4.63; D]. Dashed lines indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Table 3.

SI and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

| NGT | IGT | T2DM | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SI | |||

| SI Clamp, μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1 | 0.0717 ± 0.0076 | 0.0292 ± 0.0019*** | 0.0238 ± 0.0071*** |

| SI OGTT Matsuda (AU) | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 2.8 ± 0.3*** | 2.4 ± 0.2*** |

| SI OGTT Stumvoll, μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1 | 0.0956 ± 0.0035 | 0.0284 ± 0.0084*** | 0.0274 ± 0.0066*** |

| SI OGTT Solomon, μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1 | 0.0617 ± 0.0017 | 0.0391 ± 0.0027*** | 0.0378 ± 0.0020*** |

| Early-phase GSISOGTT 0–30 min | |||

| ΔC-peptide, pM | 1,193 ± 66 | 1,474 ± 131 | 867 ± 65**## |

| AUC C-peptide, pM/min | 35,879 ± 1,682 | 49,462 ± 3,371*** | 42,562 ± 1,932 |

| ΔC-peptide/glucose, pM/mM | 503 ± 54 | 530 ± 91 | 157 ± 45***# |

| AUC C-peptide/glucose, pM/mM) | 184 ± 8 | 223 ± 17* | 153 ± 9## |

| Late-phase GSISOGTT 30–120 min | |||

| AUC C-peptide, pM/min | 211,762 ± 9.225 | 313,497 ± 20,750*** | 243,946 ± 12,687# |

| AUC C-peptide/glucose, pM/mM | 320 ± 11 | 348 ± 26 | 201 ± 14***,## |

| Hepatic insulin extraction | |||

| Early-phase ΔC-peptide/Δinsulin (AU) | 4.38 ± 0.23 | 3.44 ± 0.25 | 4.45 ± 0.26 |

| Early-phase AUC C-peptide/Δinsulin (AU) | 6.45 ± 0.28 | 5.47 ± 0.39 | 8.27 ± 0.59**,## |

| Late-phase AUC C-peptide/Δinsulin (AU) | 6.96 ± 0.29 | 5.18 ± 0.39** | 7.19 ± 0.46# |

Data are means ± SE and indicate insulin sensitivity measured during hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp (SI Clamp) and oral glucose tolerance test (SI OGTT), and early- and late-phase oral glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSISOGTT) measured in subjects representing the entire glucose tolerance continuum. AU, arbitrary units; AUC, area under the curve. Δ = incremental value between 0 and 30 min. One-way ANOVA with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons was used to examine group differences.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01, and

P < 0.001 vs. NGT;

P < 0.01 and

P < 0.001 vs. IGT.

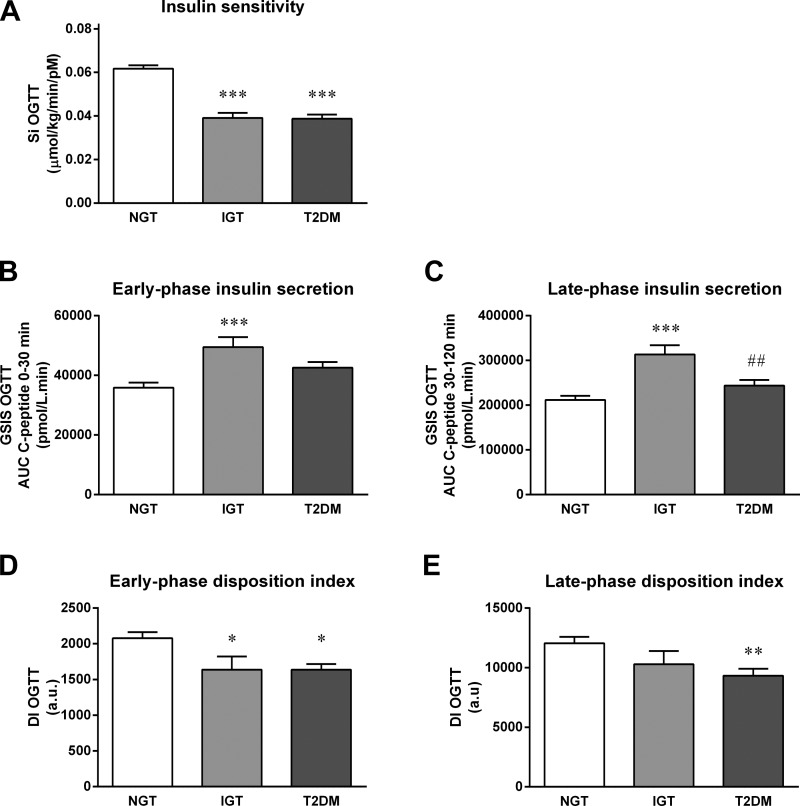

Fig. 3.

OGTT-derived measurements of insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, and disposition index. A: subjects representative of a heterogeneous population with respect to age, BMI, adiposity, and glucose tolerance status underwent a 2-h, 75-g OGTT. An OGTT-derived measurement of Si was calculated as SI OGTT (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) = 0.138 − (0.00231 × BMI) − (0.00118 × G120) − (0.0000135 × I30) − (0.00000678 × I90), where BMI = body mass index (kg/m2), G120 = plasma glucose (mmol/l) measured at 120 min during OGTT, and I30 and I90 = serum insulin (pmol/l) measured at 30 and 90 min during OGTT (n = 187). B and C: C-peptide responses during OGTT were used to determine early- (B) and late-phase glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (C) (GSISOGTT; n = 171). D and E: the product of SI OGTT and GSISOGTT was used to determine early- (D) and late-phase DI (E) (DIOGTT; n = 157) were determined. One-way ANOVA was used to test between-group differences Bonferonni-adjusted for multiple comparisons (*P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.0001 vs. NGT; ##P < 0.01 vs. IGT). Bars represent groups means ± SE. AU, arbitrary units.

Insulin secretion.

Table 3 and Fig. 3, B and C, show that both early- and late-phase GSISOGTT were higher in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance compared with normal glucose-tolerant subjects (P < 0.001). In type 2 diabetic subjects, GSISOGTT was not different compared with NGT subjects; however, late-phase GSISOGTT was lower in type 2 diabetic subjects compared with subjects with impaired glucose tolerance (P < 0.01).

Oral disposition index.

Table 4 shows the regression analysis slope (β) and confidence interval for the various comparisons between log10(GSISOGTT) and log10(SI OGTT) in the whole cohort as well as for the separate groups. One-way ANOVA comparing the β-values between groups indicates a progressive lowering of the relationship slope with advancing glucose intolerance (β = −0.34 ± 0.01, −0.26 ± 0.06, and −0.20 ± 0.02 in NGT, IGT, and T2DM, respectively; NGT vs. T2DM, P = 0.0001). Early- and late-phase GSIS as estimated by AUC C-peptide 0–30 and AUC C-peptide 30–120 min, respectively, demonstrated significant inverse relationships with SI OGTT, with the greatest r values compared with the other measures of GSIS during OGTT, and are shown in Fig. 1, C (r = −0.50, P = 0.009) and D (r = −0.49, P = 0.002). Nonlinear (log-log) regression determined that log10(early-phase GSISOGTT) = β × log10(SI OGTT) + 4.21, where β = −0.295 (95% confidence interval = −0.367 to −0.222) and log10(late-phase GSISOGTT) = β × log10(SI OGTT) + 4.99, where β = −0.294 (95% confidence interval = −0.369 to −0.218). To further validate these measurements, we also demonstrated a significant inverse relationship between SI OGTT and (early- and late-phase) GSISOGTT in an independent data set (Fig. 2, C and D). Early-phase DIOGTT was significantly lower in both IGT and T2DM subjects compared with NGT subjects (P < 0.05; Fig. 3D), whereas late-phase DIOGTT was only significantly different in T2DM subjects compared with NGT subjects (P < 0.01; Fig. 3E).

Table 4.

OGTT-derived disposition index

| Log10(SI OGTT Solomon) Vs.: | β | 95% CI | Constant | 95% CI | r Value | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | ||||||

| Log10(early-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| ΔC-pep0-30 | −0.18 | −0.31 to −0.04 | 2.83 | 2.64–3.02 | −0.19 | < 0.0001 |

| AUC C-pep0-30 | −0.29 | −0.37 to −0.22 | 4.21 | 4.10–4.32 | −0.50 | 0.009 |

| ΔC-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.20 | (−0.47 to 0.08) | 2.36 | 1.97–2.74 | −0.10 | < 0.0001 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.23 | −0.32 to −0.14 | 1.95 | 1.82–2.08 | −0.35 | 0.0009 |

| Log10(late-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| AUC C-pep30-120 | −0.29 | −0.37 to −0.22 | 4.99 | 4.88–5.10 | −0.49 | 0.002 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc30-120 | −0.18 | −0.29 to −0.08 | 2.22 | 2.07–2.36 | −0.25 | 0.10 |

| NGT subjects | ||||||

| Log10(early-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| ΔC-pep0-30 | −0.34 | −0.49 to −0.20 | 2.66 | 2.45–2.86 | −0.36 | 0.07 |

| AUC C-pep0-30 | −0.38 | −0.48 to −0.27 | 4.08 | 3.93–4.23 | −0.54 | 0.002 |

| ΔC-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.32 | −0.65 to 0.00 | 2.30 | 1.86–2.75 | −0.19 | < 0.0001 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.33 | −0.43 to −0.22 | 1.86 | 1.72–2.00 | −0.49 | 0.03 |

| Log10(late-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| AUC C-pep30-120 | −0.38 | −0.48 to −0.28 | 4.86 | 4.72–4.99 | −0.57 | 0.0005 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc30-120 | −0.31 | −0.40 to −0.21 | 2.12 | 2.00–2.25 | −0.52 | 0.37 |

| IGT subjects | ||||||

| Log10(early-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| ΔC-pep0-30 | −0.17 | −0.54 to 0.20 | 2.91 | 2.34–3.48 | −0.19 | 0.62 |

| AUC C-pep0-30 | −0.19 | −0.46 to 0.07 | 4.41 | 4.01–4.82 | −0.28 | 0.07 |

| ΔC-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.33 | −1.14 to 0.07 | 1.91 | 0.77–3.05 | −0.28 | 0.14 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.19 | −0.50 to 0.11 | 2.07 | 1.60–2.53 | −0.25 | 0.31 |

| Log10(late-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| AUC C-pep30-120 | −0.24 | −0.39 to 0.12 | 5.15 | 4.76–5.54 | −0.36 | 0.08 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc30-120 | −0.24 | −0.54 to 0.07 | 2.19 | 1.72–2.66 | −0.30 | 0.45 |

| T2DM subjects | ||||||

| Log10(early-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| ΔC-pep0-30 | −0.10 | −0.35 to 0.15 | 2.80 | 2.43–3.17 | −0.12 | 0.03 |

| AUC C-pep0-30 | −0.22 | −0.33 to −0.10 | 4.33 | 4.20–4.45 | −0.47 | 0.15 |

| ΔC-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.22 | −0.47 to 0.03 | 1.98 | 1.60–2.36 | −0.24 | 0.01 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc0-30 | −0.19 | −0.33 to −0.05 | 5.12 | 4.91–5.34 | −0.35 | 0.15 |

| Log10(late-phase GSISOGTT) | ||||||

| AUC C-pep30-120 | −0.24 | −0.39 to −0.09 | 1.85 | 1.61–2.08 | −0.40 | 0.03 |

| AUC C-pep/Gluc30-120 | −0.23 | −0.40 to −0.06 | 1.96 | 1.70–2.23 | −0.35 | 0.02 |

Data summary of the log10-log10 linear regression for comparisons between our novel OGTT-derived measurement of SI (SI OGTT) and early- (0–30 min) and late-phase (30–120 min) oral GSIS (GSISOGTT). CI, confidence interval; C-pep, serum C-peptide. In the linear model, log10(GSISOGTT) = β × log10(SI OGTT) + c, the slope of the relationship between SI OGTT and GSISOGTT is represented by β, and the y-intercept is represented by the constant c. Data are shown for the whole data set and for the individual groups of NGT, IGT, and T2DM glucose tolerance.

DISCUSSION

By using subject demographic variables and plasma biochemical data associated with glucose tolerance, multiple regression revealed that BMI and plasma glucose and insulin concentrations measured during OGTT best explained the variance in clamp-derived insulin sensitivity. This slight modification of the Stumvoll index provided a quantifiable measurement of insulin sensitivity (SI OGTT = μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) and had high agreement (typical measurement error = +3.6%) with gold standard clamp-derived measurements (SI Clamp; μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) across the whole range of the glucose tolerance continuum. We extended the former work from Stumvoll et al. (15) by developing the SI OGTT index in nondiabetic subjects and in those with type 2 diabetes and by validating our index in an independent data set, finding a slight improvement in the accuracy of the index compared with clamp-derived insulin sensitivity.

To assess prehepatic glucose-stimulated insulin responses, we measured plasma C-peptide concentrations during an OGTT, rather than plasma insulin, so that our assessment would not be confounded by hepatic insulin extraction, which is altered across the glucose tolerance continuum, as shown in Table 3 (9). To determine whether appropriate pancreatic β-cell compensation occurs in response to changes in insulin sensitivity, it is prudent to examine insulin secretion in relation to insulin sensitivity. A hyperbolic relationship between the acute (early-phase) insulin response to intravenous glucose (GSIS) and insulin sensitivity was demonstrated by Kahn et al. in 1993 (5), such that log10(GSIS) = β × log10(SI) + constant, where β = −1 and its confidence interval excluded zero. Therefore, Log10(Si) vs. log10(GSIS) is described by an inverse linear relationship. To calculate β-cell compensation for changing insulin sensitivity, the product of GSIS and SI, which is widely known as the disposition index (DI), provides an indication of whole body glucose disposition. Traditionally, DI was derived from a minimal model assessment of the intravenous glucose tolerance test, using Si and the acute plasma insulin response to glucose as a measure of GSIS. However, as explained above, peripheral blood insulin is not a good marker of prehepatic insulin levels. Furthermore, nutrients (e.g., glucose) administered via intestinal routes provide a more physiological insulin secretory stimulus and increase the “real-world” application of our assessments of insulin secretion. In this study, we confirmed the existence of an inverse log-log relationship between (early- and late-phase) GSISOGTT and SI OGTT; however, it is important to note that β was not equal to −1, and therefore, the relationship is not truly hyperbolic. It is also important to note our finding that the slope (β) of the relationship between GSISOGTT and SI OGTT gradually decreases across the glucose tolerance continuum, which suggests that compensatory insulin secretory function is reduced with advancing hyperglycemia.

Deviation from a true hyperbolic curve is likely explained by the fact that we have used C-peptide as our marker of prehepatic insulin secretion, and therefore, our measurement is not confounded by hepatic insulin extraction. However, replacing C-peptide with insulin concentrations in our analyses did not force β = −1 (data not shown). Thus, this deviation may be due to the difference in the route of glucose delivery in our OGTT setting compared with the original intravenous tests used by Kahn et al. (5). This in itself is an area that warrants attention because the role of numerous nonglucose insulin secretagogues (fatty acids, amino acids, incretin hormones, neural factors, etc.) in β-cell compensation for changing insulin sensitivity has never been defined. Some previous studies in which DI was calculated as GSIS × SI have simply assumed that an inverse relationship exists between the chosen measurements of GSIS and SI (2, 3). Other studies that have made thorough comparisons between GSIS and different OGTT-derived indices of SI (11) and validated them against intravenous methods (10) have not examined C-peptide-derived GSIS. Thus, the outcomes of those studies may not truly reflect β-cell compensation for insulin sensitivity due to the confounding effect of hepatic insulin extraction. Finally, it is also important to select variables that do not give rise to autocorrelation, as investigated by Retnakaran et al. (11). For example, correcting the homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) of β-cell function for the HOMA of insulin resistance is inappropriate because both variables are similar functions of glucose and insulin (G × I vs. I ÷ G), and therefore, correlation is highly likely. Future studies should take care to confirm that appropriate GSIS and Si variables are measured and that the two are inversely related before estimates of DI are calculated. Furthermore, because of the separate information related to the pathophysiology of diabetes that is gained from quantifying both early- and late-phase insulin secretory responses to glucose, we highlight the importance of measuring both early- and late-phase GSIS and DI in future studies.

One of the limitations of this study is that insulin sensitivity was not measured directly during OGTT. Although this is achievable using complex modeling and isotopic tracer methodology, such approaches are not feasible in the majority of physiological studies. It should also be noted that our Bland-Altman analysis indicates that at high values the SI OGTT index has a tendency to underestimate insulin sensitivity, and in the low range it has a tendency to overestimate this variable (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, the variability in the difference between SI Clamp and SI OGTT was inversely associated with age (r = −0.58, P < 0.0001), fasting glucose (r = −0.20, P < 0.05), and 2-h OGTT glucose (r = −0.36, P < 0.001) such that the difference between predicted (SI OGTT) and measured (SI Clamp) insulin sensitivity was smallest in older subjects with higher hyperglycemia. It is also important to note that one of the reasons that our new SI OGTT index outperforms other indices is because those previously derived indices were not derived using our subject population. That said, it is of importance that our index provides a quantifiable measurement (μmol·kg−1·min−1·pM−1) of insulin sensitivity that can be compared directly with insulin-mediated glucose disposal rates measured during clamps, and we validated this finding in a separate cohort of n = 40 subjects. It should be considered, however, that the subjects included in our diabetic cohort had rather well-controlled glycemia with relatively early-stage disease. Future work is required to validate this new index in poorly controlled diabetics with advanced disease. Nonetheless, the strength of this study is that we have validated an insulin sensitivity index and derived a DI, which was measured during an OGTT in a large sample size representing the entire glucose tolerance continuum over a wide range of age and BMI in adults.

The most important clinical variable measured during an OGTT is the plasma glucose concentration because it directly reflects the degree of glucose tolerance and indicates the risk of developing hyperglycemia-related comorbidities. Hyperglycemia associated with type 2 diabetes develops when insulin secretion no longer compensates for poor insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues, indicating a state of β-cell dysfunction. In the research setting where the causes of hyperglycemia are of interest, determining accurate assessments of insulin sensitivity and β-cell function during an OGTT is essential so that mechanistic questions can be answered. In obesity-related disease, the degree of glucose tolerance is determined by the level of β-cell compensation in relation to changing insulin sensitivity. In conclusion, this work indicates that the OGTT can provide a simple measure of that phenomenon in people across the entire glucose tolerance continuum.

GRANTS

This work was funded by a Paul Langerhans Program Grant from the European Foundation for the Study of Diabetes/Amylin (T. P. J. Solomon). Additional support came from the Danish Center for Strategic Research in Type 2 Diabetes (B. K. Pedersen; Danish Council for Strategic Research, Grant Nos. 09-067009 and 09-075724) and National Institute on Aging Grant RO1-AG-12834 (J. P. Kirwan). S. K. Malin was supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases T32 grant (DK-007319). The Centre of Inflammation and Metabolism is supported by a grant from the Danish National Research Foundation (DNRF55). The Centre for Physical Activity Research is supported by a grant from Trygfonden.

DISCLOSURES

The authors have nothing to declare.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.P.S., J.M.H., B.K.P., and J.P.K. conception and design of research; T.P.S., S.K.M., K.K., S.H.K., J.M.H., M.J.L., M.P., and J.P.K. performed experiments; T.P.S., K.K., S.H.K., J.M.H., M.J.L., and M.P. analyzed data; T.P.S., S.K.M., K.K., J.M.H., M.P., B.K.P., and J.P.K. interpreted results of experiments; T.P.S. prepared figures; T.P.S. drafted manuscript; T.P.S., S.K.M., K.K., S.H.K., J.M.H., M.J.L., M.P., B.K.P., and J.P.K. edited and revised manuscript; T.P.S., S.K.M., K.K., S.H.K., J.M.H., M.J.L., M.P., B.K.P., and J.P.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Julianne Filion (Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH) for clinical nursing support and Lisbeth Andreasen (Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark) for assistance with biochemical assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab Gastrointest Physiol 237: E214–E223, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gastaldelli A, Ferrannini E, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Beta-cell dysfunction and glucose intolerance: results from the San Antonio metabolism (SAM) study. Diabetologia 47: 31–39, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gastaldelli A, Ferrannini E, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, Mari A, DeFronzo RA. Thiazolidinediones improve β-cell function in type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E871–E883, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jallut D, Golay A, Munger R, Frascarolo P, Schutz Y, Jequier E, Felber JP. Impaired glucose tolerance and diabetes in obesity: a 6-year follow-up study of glucose metabolism. Metabolism 39: 1068–1075, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kahn SE, Prigeon RL, McCulloch DK, Boyko EJ, Bergman RN, Schwartz MW, Neifing JL, Ward WK, Beard JC, Palmer JP. Quantification of the relationship between insulin sensitivity and beta-cell function in human subjects. Evidence for a hyperbolic function. Diabetes 42: 1663–1672, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirwan JP, Solomon TP, Wojta DM, Staten MA, Holloszy JO. Effects of 7 days of exercise training on insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E151–E156, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knudsen SH, Hansen LS, Pedersen M, Dejgaard T, Hansen J, Hall GV, Thomsen C, Solomon TP, Pedersen BK, Krogh-Madsen R. Changes in insulin sensitivity precede changes in body composition during 14 days of step reduction combined with overfeeding in healthy young men. J Appl Physiol 113: 7–15, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22: 1462–1470, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meier JJ, Veldhuis JD, Butler PC. Pulsatile insulin secretion dictates systemic insulin delivery by regulating hepatic insulin extraction in humans. Diabetes 54: 1649–1656, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Retnakaran R, Qi Y, Goran MI, Hamilton JK. Evaluation of proposed oral disposition index measures in relation to the actual disposition index. Diabet Med 26: 1198–1203, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Retnakaran R, Shen S, Hanley AJ, Vuksan V, Hamilton JK, Zinman B. Hyperbolic relationship between insulin secretion and sensitivity on oral glucose tolerance test. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16: 1901–1907, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Solomon TP, Haus JM, Kelly KR, Rocco M, Kashyap SR, Kirwan JP. Improved pancreatic beta-cell function in type 2 diabetic patients after lifestyle-induced weight loss is related to glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide. Diabetes Care 33: 1561–1566, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solomon TP, Sistrun SN, Krishnan RK, Del Aguila LF, Marchetti CM, O'Carroll SM, O'Leary VB, Kirwan JP. Exercise and diet enhance fat oxidation and reduce insulin resistance in older obese adults. J Appl Physiol 104: 1313–1319, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steele R. Influences of glucose loading and of injected insulin on hepatic glucose output. Ann NY Acad Sci 82: 420–430, 1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Jarvinen H, Van HT, Renn W, Gerich J. Use of the oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care 23: 295–301, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]