Abstract

Congenital distal renal tubular acidosis (RTA) from mutations of the B1 subunit of V-ATPase is considered an autosomal recessive disease. We analyzed a distal RTA kindred with a truncation mutation of B1 (p.Phe468fsX487) previously shown to have failure of assembly into the V1 domain of V-ATPase. All heterozygous carriers in this kindred have normal plasma HCO3− concentrations and thus evaded the diagnosis of RTA. However, inappropriately high urine pH, hypocitraturia, and hypercalciuria were present either individually or in combination in the heterozygotes at baseline. Two of the heterozygotes studied also had inappropriate urinary acidification with acute ammonium chloride loading and an impaired urine-blood Pco2 gradient during bicarbonaturia, indicating the presence of a H+ gradient and flux defects. In normal human renal papillae, wild-type B1 is located primarily on the plasma membrane, but papilla from one of the heterozygote who had kidney stones but not nephrocalcinosis showed B1 in both the plasma membrane as well as diffuse intracellular staining. Titration of increasing amounts of the mutant B1 subunit did not exhibit negative dominance over the expression, cellular distribution, or H+ pump activity of wild-type B1 in mammalian human embryonic kidney-293 cells and in V-ATPase-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. This is the first demonstration of renal acidification defects and nephrolithiasis in heterozygous carriers of a mutant B1 subunit that cannot be attributable to negative dominance. We propose that heterozygosity may lead to mild real acidification defects due to haploinsufficiency. B1 heterozygosity should be considered in patients with calcium nephrolithiasis and urinary abnormalities such as alkalinuria or hypocitraturia.

Keywords: V-ATPase, haploinsufficiency, kidney stones, distal renal tubular acidosis

renal tubular acidoses (RTAs) are tubulopathies where nonvolatile acid accumulates because of decreased tubular secretion of acid by the proximal or distal nephron, which can result from congenital or acquired causes (19, 31). Distal H+ excretion requires carbonic anhydrase to generate an acid-base pair (H+ and HCO3−) to furnish substrate for acid-base transporters. Luminal translocation of H+ from the cell into the urine is mediated by V-ATPase, and concurrent basolateral exit of HCO3− into the plasma occurs via anion exchanger 1 (AE1) (68). It is not mere coincidence that congenital forms of distal RTA (dRTA) in humans result from inactivating mutations of carbonic anhydrase II enzyme (23, 53, 55), the B1 or a4 subunits of V-ATPase (60, 67), or the AE1 Cl−-base exchanger (6, 7, 11).

These candidate genes were identified using classical genetics on kindreds derived from probands initially identified by clinicians. In general, phenotypic information is limited to clinical diagnosis of RTA based on hypobicarbonatemia without elevation of plasma anion gap or creatinine and concomitant unduly alkaline urine pH. The disorder may be brought to clinical attention by complications such as growth retardation, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis (31). Most clinical data are limited to plasma HCO3− concentration and spot urinary pH with no further phenotypic characterizations.

Congenital dRTA usually follow autosomal recessive inheritance with the exception of some mutations of AE1, which are autosomal dominant. The basis for the recessive nature is usually attributed to adequacy of the normal functioning transporters provided by the single wild-type allele, or haplosufficiency. In the case of AE1-related autosomal dominant dRTA (6, 11, 25, 29, 57, 69), in vitro data have suggested that mutant AE1 may prevent wild-type AE1 from reaching the membrane via heterodimerization or by mistargeting of the mutant to the apical membrane, thereby nullifying apical H+ secretion (13, 49, 50, 64). This dominant model by mutant AE1 remains to be proven in vivo. Other than these AE1 mutations, the accepted paradigm is that one needs two mutant alleles to produce dRTA. However, the foundation of this paradigm is based on the absence of overt clinical diagnoses in heterozygotes.

The clinical diagnosis of dRTA depends on the stringency of the definition and how one sets the threshold for defining renal acid underexcretion. Since metabolic acidosis is not a dichotomous trait, a forme fruste of dRTA can conceivably eclipse detection by conventional clinical tests, and indepth metabolic studies are not usually performed by practitioners. Wrong and coworkers (16, 71) recognized that defective distal renal acidification can be associated with a normal plasma HCO3− concentration and set the precedence for using acute acid loading to uncover renal acidification defects. Interestingly, a considerable fraction of the literature on this type of incomplete dRTA actually stems from patients with kidney stones. While most patients with calcium oxalate stones can maximally acidify their urine, up to 30% of patients with calcium phosphate stones have reduced ability to lower their urine pH (2, 22, 45, 46). Impaired maximal acidification is also more common in recurrent stone formers and those with bilateral disease (2, 12, 15, 30, 43, 44, 54, 61, 63). No one investigated the basis for these subtle acidification anomalies.

Distal apical H+ secretion is mediated by V-ATPase (5, 27), which belongs to a family of ATP-energized H+-translocating ion pumps (18). V-ATPases acidify intracellular organelles, which is essential for receptor-mediated endocytosis, lysosomal hydrolysis, intracellular protein targeting, processing of hormones, and uptake and storage of neurotransmitters. In specialized cells, plasma membrane-situated V-ATPases are instrumental in the regulation of bone resorption, synaptic transmission, endolymph pH regulation, and renal acid excretion. V-ATPases are complex proteins composed of at least 13 different subunits organized into 2 distinct functional domains: a peripheral catalytic sector 650-kDa V1 domain (A3B3C1D1E3F1G3H1) and an intramembranous 260-kDa proteolipid V0 domain [a1d1c″1(c′,c)6] (24). In mammals, B1 is restricted to epithelia of the inner ear, epididymis, and distal renal tubule. Mutations in the B1 subunit gene ATP6V1B1 are responsible for autosomal recessive dRTA with deafness (19, 28, 56, 60). The mechanisms by which some B1 subunit mutations lead to V-ATPase dysfunction were unknown until recently, when the majority of mutant B1 subunits were shown to fail to incorporate into the V1 subunit (20, 73).

We posed the simple but fundamental question of whether heterozygous carriers of mutant B1 have any detectable renal acidification abnormalities. In addition, if they do, is there evidence for negative dominance? We took a family known to harbor an inactivating truncation mutation of B1 (21) and studied the heterozygous members for abnormalities in renal acidification, prompted by the fact that one of the heterozygotes developed severe kidney stones. Despite the fact that none of the heterozygotes carry the clinical diagnosis of RTA, we obtained evidence that the heterozygotes have abnormal baseline steady-state urinary chemistry, and two heterozygotes showed abnormal urinary acidification upon provocation. Because of the previous postulation of negative dominance of the mutant B1 subunit over the wild-type subunit (73), we used in vitro biochemical, mammalian cell expression, and yeast complementation approaches to examine for this possibility. We conclude that the affected heterozygotes in our kindred are in a state of haploinsufficiency where the pump from the normal allele can sustain normal clinical chemistry but the burden of heterozygosity in this family is incomplete dRTA. Individuals with incomplete dRTA or calcareous nephrolithiasis with distinct chemical abnormalities should be considered as potential heterozygous carriers of mutant B1 alleles.

METHODS

Patient experiments.

Subjects were recruited from University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center clinics with approval by the Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave informed consent. Normal subjects comprised staff and students on campus. A systemic multichannel analysis was used for serum analytes (Beckman CX9ALX, Beckman, Fullerton, CA). Serum pH and Pco2 were measured using a Radiometer ABL 5 (Radiometer America, Westlake, OH). Urine creatinine was measured via the picric acid method, sulfate was assessed by ion chromatography, ammonium was assessed by the glutamate dehydrogenase method, and citrate was assessed enzymatically (Boehringer-Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN).

The ammonium chloride load test was conducted as previously described (33). Fasted subjects had urine collected hourly from 0700 to 1200 hours under mineral oil. At 0800 hours, 50-meq ammonium chloride gelatin capsules were administered orally in two to four divided doses over 30 min. Water (250 ml) was given at 0700, 0800, 0900, 1000, and 1100 hours. Arterialized venous blood was obtained for chemistry and pH and blood gases at 0700, 1000, and 1200 hours. Urine was collected for 4–6 h depending on the response to the acid load. To perform urine minus blood Pco2, which yields a surrogate for H+ flux in the presence of bicarbonaturia (17, 62), two forearm intravenous catheters were inserted: one for NaHCO3 infusion and the other for blood sampling. Sodium bicarbonate (250 meq) in 750 ml was infused, and urine was collected every 30 min until the urine pH was >7.0, and the urine was then collected every 15 min for three times and analyzed for Pco2, pH, total volume, and creatinine. Venous blood was drawn before the infusion and at the time of each of the last three urine collections for Pco2 and pH.

For immunohistochemistry of the human kidney, intraoperative medullary biopsy samples (approved by the Institution Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center) were immersion fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (4°C for 4 h). After being washied with PBS (4°C overnight), tissues were frozen in OCT, and 4-μm sections were cut and washed with PBS (for 15 min) followed by 0.1% Triton X-100 incubation (10 min). Sections were incubated with a blocking solution (PBS, 3% BSA, and 10% goat serum for 60 min) and then rabbit polyclonal anti-B1 antibody (1:100; 4°C overnight) (47). After being washed with PBS, sections were incubated with Alexa fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and then with 1:80 rhodamine phalloidin (Invitrogen). After additional PBS washes, sections were mounted and then visualized with a Zeiss LSM510 microscope.

Mammalian cell expression experiments.

PCR-generated cDNA fragments were inserted in frame into COOH-terminal single hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged PMH (Roche) or NH2-terminal FLAG-tagged p3xFLAG-CMV-10 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) vectors for mammalian expression. Synonomous mutations in B1 were created by a QuikChange Multi Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Agilent Technologies). All constructs were verified by sequencing. Human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells [American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)] were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) in high-glucose (450 mg/dl) DMEM (GIBCO-BRL) supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS, penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Transfections were performed with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and cells were used 48 h later. The design of the small interfering (si)RNAs is shown in Fig. 3A, and siRNAs were custom synthesized by Invitrogen and added to cells at a final concentration of 200 pM.

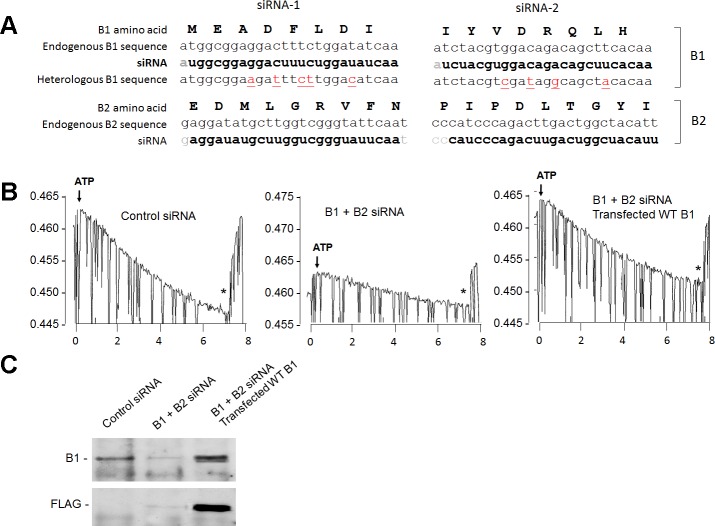

Fig. 3.

Mammalian cell expression system. Endogenous B1 and B2 were knocked down in human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells, and V-ATPase function was measured in isolated endosomes. A: design of the small interfering (si)RNAs targeting B1 and B2 and protection of the heterologously transfected B1. B: original tracings of the acridine orange assay. HEK-293 cells were transfected with control siRNA (left), combined B1 + B2 siRNA (middle), or B1 + B2 siRNA along with FLAG-tagged WT human B1 with synonomous mutations as shown in A (right). Tracings show ATP-induced endosomal acidification followed by the collapse of the pH gradient by H+ ionophore 1799 (*). C: experimental conditions were similar to those in B. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with anti-B1 or anti-FLAG antibody.

Immunoblots and immunoprecipitation were performed as previously described for these cells (20). The primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-B1 antibody, rabbit polyclonal (Xie Lab) and mouse monoclonal (SC-55544, Santa Cruz Biotechnology); anti-FLAG antibody, rabbit polyclonal antibody (F7425, Sigma) and mouse monoclonal (F3165, Sigma); and anti-HA antibody, rabbit polyclonal (SAB4300603, Sigma) and mouse monoclonal (H3663, Sigma). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse and donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were used at 1:20,000 to 1:10,000 dilutions, and signals were detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ).

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lyzed in buffer [containing 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8), 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 100 μg/ml PMSF, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, and 2 μg/ml pepstatin A], and lysates were cleared by centrifugation (14,000 g for 30 min). Precipitating antibodies (1:200 dilution) followed by prewashed protein G-agarose (50% slurry) were added (4 h at 4°C). After being washed with lysis buffer (3 times), proteins were eluted from the beads with 2.5× loading buffer [2.5 mM Tris·Cl (pH 6.8), 2.5% SDS, 2.5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 25% glycerol], heated (95°C for 2 min), resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, and probed with the stated primary antibodies.

For immunocytochemistry, HEK-293 cells were fixed 48 h after transfection with 4% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and blocked by 3% BSA and 10% goat serum for 1 h. Specimens were incubated with anti-FLAG mouse monoclonal antibody. Fluorescence images were acquired through a Zeiss ×100 objective lens using a Zeiss LSM-510 laser scanning confocal microscope.

Microsomal vesicles were isolated from HEK-293 cells (two 10-cm dishes) as previously described (32). The cell pellet was resuspended in ice-cold hypotonic lysis buffer [10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 1 mM EDTA, 5 μM diisopropyl fluorophosphate, 10 μg/ml pepstatin A, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 mg/ml benzamidine] and then homogenized by 10 strokes in a tight fitting Dounce followed by 15 strokes after the addition of an equal volume of sucrose buffer (500 mM sucrose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2). The lysate was centrifuged (600 g for 15 min), the secondary supernatant was centrifuged again (100,000 g for 45 min), and the pellet was resuspended in buffer (250 mM sucrose and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.2) at 2–6 mg/ml protein. Vesicular H+ pumping was assessed by measurements of acridine orange absorbance quenching in a SLM-Amino DW2-C dual wavelength spectrophotometer (change in absorbance at 492–540 nm) (14, 72). Vesicles (300 μg) were diluted into 1.6 ml assay buffer [200 mM NaCl, 30 mM Na-tricine (pH 7.5), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA, and 6 μM acridine orange]. Reactions were initiated by the addition of ATP (final concentration: 1.3 mM) and valinomycin (final concentration: 1 μM) and were terminated by the addition of 1.6 μM of H+ ionophore 1799.

Yeast transformation and growth selection.

COOH-terminally HA-tagged expression constructs in p426TEF or p425TEF vectors (35) were transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain YBR127C (genotype MATa/MATalpha his3Δ1/his3Δ1 leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0 lys2Δ0/+ met15Δ0/+ ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0 ΔVMA2/ΔVMA2, ATCC) and grown at 30°C in YEPD medium (10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l peptone, 20 g/l d-glucose, and 100 mg/l adenine hemisulfate) or synthetic minimal uracil and leucine (SD -UL) dropout medium (-uracil and leucine DO supplement, 6.7 g/l nitrogen base, 20 g/l d-glucose, 100 mg/l adenine hemisulfate, and 50 mM MES, pH 5.5). All yeast media contained 200 μg/ml geneticin. Transformation was performed as previously described by Gietz et al. (52). Single colonies were isolated on pH 5.5 SD -UL plates, and the growth of transformants was assessed on YEPD plates buffered to pH 5.5 with 50 mM MES or pH 7.5 with 50 mM MOPS.

For immunoblot analysis, 10 optical density units of yeast were washed once with 1 mM EDTA-H2O and lysed in 2 M NaOH (10 min, 4°C). Proteins were isolated by trichloroacetic acid/acetone precipitation, resuspended in SDS sample buffer [25 mM Tris·Cl (pH 6.8), 9 M urea, 1 mM EDTA, 1% (wt/vol) SDS, 0.7 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% (vol/vol) glycerol], separated by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by immunoblot analysis as described above.

RESULTS

Pedigree, clinical phenotype, and 24-h urine chemistry.

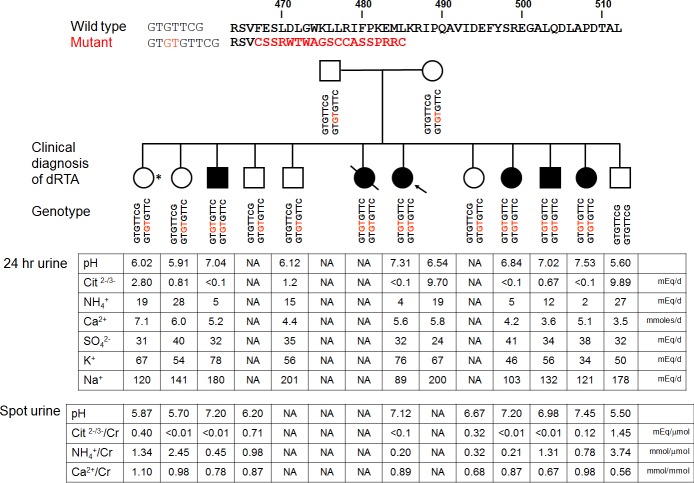

Figure 1 shows the pedigree previously partially described (3, 21). The family members have advanced in age since the original publication (3), but the clinical diagnoses have not changed, with six family members carrying the diagnosis of dRTA. One heterozygote carrier presented with urolithiasis with a heavy stone load, which required surgical intervention (asterisk in Fig. 1). Interestingly, she also had unduly alkaline urine and unexplained hypocitraturia, which cannot be explained by unusual acid intake (urinary SO4 excretion: 31 meq/day) or alkali intake (urinary K+ excretion: 67 meq/day, estimated net gastrointestinal alkali absorption: 27 meq/day) (65). The combination of high urine pH and hypocitraturia suggest defective urinary acidification. This prompted us to screen the rest of the family. Stone risk profiles from 24-h or spot urines are shown in Fig. 1. Although none of the heterozygotes carriers were previously recognized by their physicians as having dRTA, all of them showed some degree of urinary abnormalities, such as hypocitraturia and hypercalciuria, that cannot be attributable to secondary causes. Some of them also have urine pHs that are slightly alkaline, but since these were obtained on outpatient random diets, one cannot definitely conclude on abnormality. We could not identify asymptomatic stones in the rest of the family members because the subjects declined imaging experiments.

Fig. 1.

Top: genotype and phenotype of the pedigree. A GC insertion leads to loss of a phenylalanine and a frame shift, resulting and premature termination (p.Phe468fsX487). The arrow indicates the proband. *The patient without frank renal tubular acidosis (RTA) who presented with kidney stones. dRTA, distal RTA. Bottom: 24-hour and spot urine values. NA, not available.

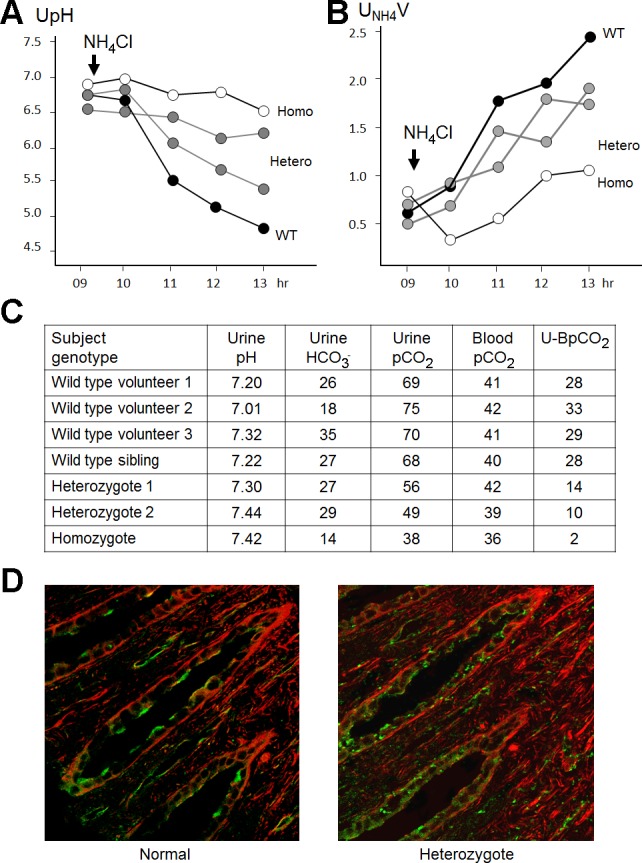

H+ gradient and H+ flux measurements in heterozygotes.

Some but not all family members consented to participate in more detailed metabolic experiments. To test whether the collecting duct can generate and sustain a high H+ gradient, we loaded the subjects with ammonium chloride to induce maximal H+ pumping. This maneuver has been shown to maximally lower urine pH in normal individuals (16, 51, 71). The two heterozygotes lowered their urine pH and increased ammonium excretion, but their urine pHs were not as low as the normal sibling (Fig. 2, A and B). The urinary ammonium excretion was numerically lower than but probably not that different from the wild type. The small numbers did not permit meaningful statistical analysis. The response in the homozygous patient was basically flat.

Fig. 2.

NH4Cl and HCO3− loading tests as well as immunohistochemistry of B1. Four members of the family consented to acidification experiments. Homo, homozygous mutant; Hetero, heterozygous carriers; WT, wild type. A: urine pH (UpH) changes with NH4Cl load. B: urinary NH4 excretion rate (UNH4V) with NH4Cl load. C: urine and blood values from the NaHCO3 loading test. U-BPco2, urine minus blood Pco2. D: staining for B1 in the renal medulla. One heterozygous family member required surgery for nephrolithiasis and had an intraoperative biopsy. B1 was stained with an antibody that reacts with both WT and mutant B1 (green). β-Actin counterstain is shown in red. One normal subject is shown, but independent staining of three normal individuals showed similar results.

Acidic urine implies adequate pump and epithelial integrity to generate and maintain pH gradients. Since secretion of a small amount of H+ into the urine across a tight epithelium can theoretically maintain a high H+ gradient, this does not guarantee adequate flux of H+ to excrete the acid load. To examine that, we use the urine minus blood Pco2 test to estimate H+ flux (62). Under high luminal HCO3− concentration, the generation of luminal CO2 can only result from titration of luminal HCO3− from high rates of apical H+ secretion. Of the heterozygous subjects tested, none of them mounted a normal Pco2 gradient (Fig. 2C).

The combination of abnormal steady-state baseline 24-h urine parameters and abnormal H+ gradient and H+ flux upon challenge beget the conclusion that these heterozygous individuals do not have normal urinary acidification and actually fit the criteria for incomplete dRTA.

Calcareous kidney stone and B1 expression in situ in a heterozygote.

This investigation was initiated by one family member who presented with calcareous stones of significant load that eventually required surgical intervention. Somewhat unexpected was that the stone composition was not the calcium phosphate typically expected of dRTA patients. Instead, the subject had 80% calcium oxalate and 20% calcium phosphate stones. There was no evidence of nephrocalcinosis by a preoperative noncontrast computerized tomography scan (not shown), intraoperative inspection, and tissue histology. An intraoperative biopsy of the papillary tip in this patient revealed an abnormal cellular pattern of the B1 subunit. While the distribution of B1 in an unrelated normal individual showed mostly apical staining, the affected heterozygote showed a mixture of both apical and rather prominent diffuse intracellular staining (Fig. 2D). Our anti-B1 antibody does not recognize truncated B1; thus the signal likely represents wild-type B1 in V1 domains that did not assemble into V0V1. The rest of the family members had no documented history of stones, but they did not consent to imaging experiments in the absence of a clinical diagnosis.

Examination for negative dominance in mammalian cells.

The metabolic phenotypes indicated that the only truly normal individual in this family was the homozygous wild-type male member. In this kindred, most heterozygotes seemed to exhibit some abnormal (albeit mild) renal acidification. This can be due to either a dominant negative effect of mutant truncated B1 or haploinsufficiency of wild-type B1.

We previously characterized the p.Phe468fsX487 truncation mutation as one that prevents proper assembly of B1 into V1, and the defect is not due to the loss of the PDZ binding motif at the COOH terminus (21). HEK-293 cells express both B1 and B2 subunits (RT-PCR; data not shown), which do not furnish a clean system to study transfected proteins. We knocked down the endogenous B subunits with siRNAs and engineered synonomous nucleotide mutations in transfected human B1 to protect it from the siRNA (Fig. 3A). siRNA reduced endogenous V-ATPase activity to ∼25–30% of normal without affecting the expression of transfected FLAG-tagged B1 (Fig. 3B). This knockdown is necessary to examine the function of heterologously expressed B1 as the endogenous B activity is strong and precludes functional readout of the transfected B1 (Fig. 4A).

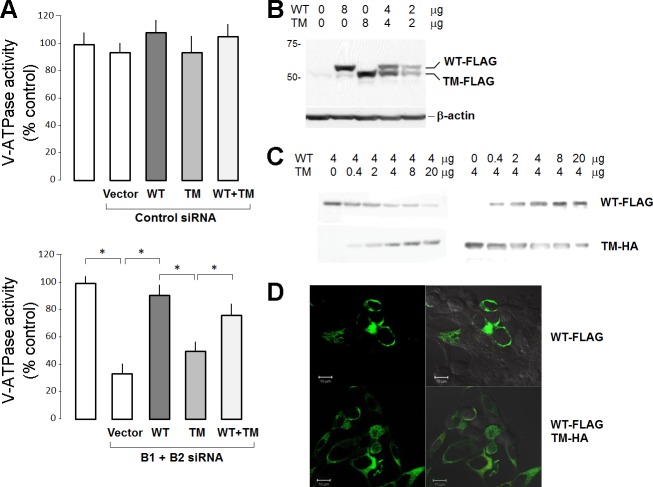

Fig. 4.

Heterologous expression of WT and truncation mutant (TM) B1 in HEK-293 cells. A: V-ATPase function in endosomes was measured as ATP-induced acidification and expressed as a percentage of untransfected control cells. Top, WT and TM B1 were transfected into HEK-293 cells with scrambled control siRNA. Bottom, WT and TM B1 were transfected into HEK-293 cells where endogenous B1 and B2 were knocked down with siRNA. Each bar represents mean ± SE from three independent transfections with triplicate plates per transfection. Statistically significant differences were assessed by ANOVA. *P < 0.05. B: immunoblot of transfected FLAG epitope-tagged WT and TM B1 in conditions identical to those in A, bottom. C: titration of transfected WT (FLAG tagged) and TM B1 [hemagglutinin (HA) tagged] where the amount of cDNA of one was kept constant and the other varied. D: HEK-293 cells were transfected with 4 μg FLAG-tagged WT B1 (top) or 4 μg FLAG-tagged WT B1 with 8 μg HA-tagged TM B1 (bottom) and stained with anti-FLAG antibody. Left, fluorescent images only; right, results superimposed on DIC images.

The transfected wild-type B1 conferred robust V-ATPase activity, whereas mutant B1 was inactive (Fig. 4A). Cotransfection of mutant B1 appeared to reduce the H+ pump activity of wild-type B1 (Fig. 4A). At face value, this appears to support a dominant negative effect of the mutant over wild-type B1. However, one needs to exercise caution in this finding. The reduction of wild-type activity can be explained by the fact that cotransfection of mutant B1 decreases the expression of wild-type B1 (Fig. 4, B–D). When normalized for the wild-type B1 antigen, the V-ATPase activity of cotransfected cells was actually normal.

To further confirm this point, we kept the amount of wild-type B1 constant and gradually increased the truncated mutant and searched for the presence of interference. When transfected mutant B1 expression was increased, the transfected wild-type B1 expression appeared to be decreased (Fig. 4C). However, a similar effect was seen in the converse experiment, where increasing wild-type B1 expression decreased mutant B1 expression (Fig. 4C). When both B1 subunits are driven to extremely high levels by strong promoters in these transient expression experiments, the two subunits may be competing for the same limited translational machinery. We fathom that this is in fact the more likely explanation than a dominant negative effect of the mutant on translation of wild-type B1.

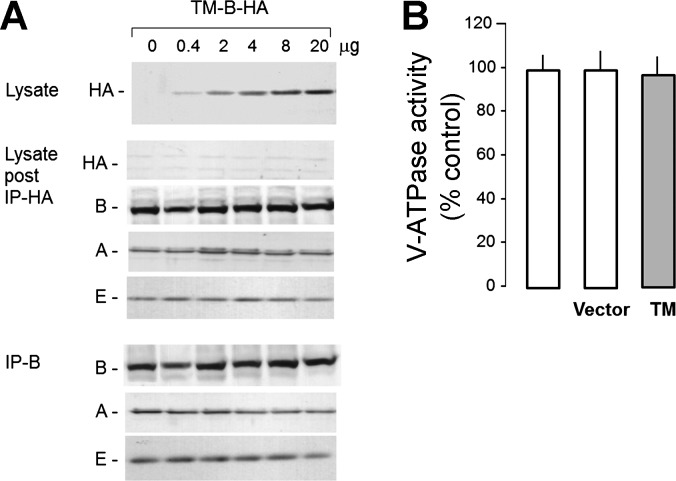

To further test this hypothesis, we examined whether transfection of exogenous mutant B1 affects the expression of native B1 and its ability to assemble. As shown in Fig. 5, exogenous mutant B1 did not affect the level of native B1 expression, assembly, or function. This speaks strongly against a dominant negative effect of mutant B1 on native wild-type B1.

Fig. 5.

Effect of TM B1 on native B1 in HEK-293 cells. TM B1 was transfected into HEK-293 cells, and its effects on native B1 expression and assembly with other subunits were studied. After cell lysis, transfected heterologous TM B1 was removed by immunodepletion with anti-HA antibody beads, and native B1 was immunoprecipitated with anti-B1. The immunocomplex was resolved by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted for the antigens stated. A, top: immunoblot of transfected TM B in cell lysates with anti-HA. Middle, immunoblot of lysates after capture of TM B by immunoprecipitation (IP) for TM B HA, native B, A, and E subunits that are part of V1. Bottom, immunoblot of the native B immunocomplex by anti-B. The complex was immunoblotted for B, A, and E subunits, which are parts of V1. B: endosomal V-ATPase activity in untransfected, vector-transfected, and TM B-transfected HEK-293 cells.

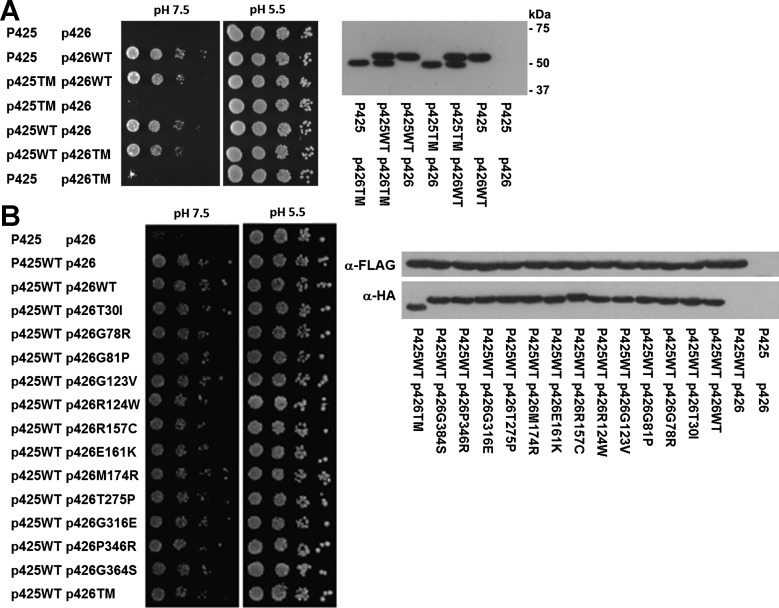

Examination for evidence of negative dominance in yeast.

To thoroughly refute the dominant negative hypothesis, we used a second system to test for dominance. Yeast provides an ideal system for studying transporters in general because of the ease in obtaining definitive genetic null cells and the ability to use growth as a functional screen; thus, this host has been used extensively for studying V-ATPase subunits (26, 48). Therefore, an independent test of negative dominance by the mutant B1 subunit is H+ pumping function in yeast, which is critical to confer the ability to grow in pH 7.5. As previously shown, human B1 complements the yeast homolog well in a growth assay (21). In null yeast, the presence of mutant B1 did not affect the expression level of B1 or the ability of wild-type B1 to support growth in pH 7.5 (Fig. 6A). This provides additional evidence showing that the truncated mutant protein exerts no significant effects on wild-type B1. We further examined whether there was any evidence of negative dominance in 12 other known human mutations to complete an exhaustive search using the yeast model. None of these mutants affected the ability of wild-type B1 to complement pump function in null yeast, and none of these mutations affected the level of B1 expression (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Expression of WT and TM B1 in yeast. Expression plasmids p425TEF and p426TEF are described in methods. P425 and p426 denote plasmid only. WT and various human B1 mutations are shown. A, left: the yeast growth assay is permissive at pH 5.5 and restrictive at pH 7.5. A total of 5 × 104 yeast cells were plated with serial 10-fold dilutions from left to right, and growth was assessed after 4 days. Right, expression of WT and TM COOH-terminally HA-tagged human B1 constructs in yeast. Equal amounts of yeast lysates of 10 optical density units were loaded. Immunoblot analysis was performed with a monoclonal anti-HA antibody. B: 12 other documented naturally occurring human B1 mutations were tested in a similar fashion in null yeast as described above. Left, yeast growth assay. Right, immunoblot.

DISCUSSION

Inactivating mutations of the V1 subunit B1 and the V0 subunit a4 are associated with congenital autosomal recessive dRTA with sensorineural hearing loss (28, 56, 58, 60, 67). The mechanism of dysregulated acidification from B1 mutations was unclear until recently, when disrupted V-ATPase assembly in vitro was described as one mechanism for seven known ATP6V1B1 missense mutations (20, 73). The finding of abnormal acidification in the heterozygous carriers in this kindred was unexpected but unequivocal. The question is why these subjects should be abnormal given that they have one normal copy of B1 and, as far as we know, B1 expression is biallelic.

The current stoichiometric model of V1 (A3B3C1D1E3F1G3H1) confers a 0.875 (1–0.53) probability of incorporating at least one abnormal B1 subunit. A heterogeneous wild-type/mutant B1 can conceivably affect ATP hydrolysis by A3B3 and impair pump function. However, we cannot find evidence showing that the truncated B1 is capable at all of incorporation into V1. However, mutant B1 can theoretically affect the synthetic pathway of wild-type B1 if both alleles are translated together. Based on the observation that overexpressed mutant B1 subunits can lower Na+-independent cell pH recovery after acid load in a rat IMCD cell line, Yang and coworkers (73) proposed a dominant negative mechanism of transfected mutant B1 subunits over native wild-type B1 subunits. However, in the background of native B1, the effect of the transfected protein is not easy to assay and certainly difficult to interpret. We reduced endogenous B1 to levels where we could see the activity of the transfected protein, and the initial results hinted at the possibility of negative dominance (Fig. 4A). However, any reduction in wild-type B1 activity was in fact seen only in the situation where both transfected proteins were driven to very high levels. Mutant B1 did not exert any dominant effect over wild-type B1 expression, assembly, or function (Figs. 5 and 6). To complete our search, we studied 12 naturally occurring human B1 mutations in null yeast and failed to find any dominant negative action for any of them. Although this was a single sample, the heterozygous carrier exhibited an abnormal pattern of staining of B1 in the renal medulla, which we interpret as unassembled mutant B1. The higher than expected intracellular staining likely represents the failure of mutant B1 to incorporate into V1, as we have observed in cell culture (20). At the moment, the data in concert support the de facto conclusion that the clinical burden of heterozygosity in this family is likely due to haploinsufficiency.

We are cognizant of the fact that not all families with dRTA are linked to either ATP6V1B1 or ATP6V0A4 (56), suggesting possible additional loci and mechanisms for congenital dRTA. We cannot rule out the possibility that our clinical and metabolic findings can be related to other putative loci that modify urinary acidification. Nephrolithiasis or nephrocalcinosis are common in subjects with dRTA (4, 8, 9, 66) due to the combination of alkaline urine and hypocitraturia and, to some extent, hypercalciuria (8, 37, 39, 40), although abnormalities in stone inhibitors, such as glycosaminoglycans and nephrocalcin, have also been proposed (36). These urinary abnormalities promote all calcium stones but, in particular, calcium phosphate stones, which is compatible with human population data that show increased prevalence of renal acidification defect in calcium phosphate stone formers (22, 45, 46).

Although there is universal agreement that calcium stones are common in dRTA, the consensus is that dRTA is a rare cause of kidney stones. However, decades of patient data have provided unequivocal evidence for impaired renal acidification in the general stone-forming population without frank Mendelian dRTA. In 7 studies (12, 38, 41, 42, 59, 61, 70) amounting to >1,000 stone formers, abnormalities in urinary acidification have been found in an average of 17% (range: 6–26%) of all-comers. Whereas the first stone suffer may have a <10% chance of abnormal renal acidification (43), in recurrent stone formers, the frequency has been estimated from 7% to 100% in 7 studies totaling >200 patients (1, 2, 10, 34, 44, 54, 63). Abnormalities in acidification are also more common in bilateral stones, ranging in prevalence from 36% to 64% in a total of 228 patients (15, 44).

The clinical data suggest prevalent defective renal acidification even in the general stone-forming population and is staggeringly high in specific subgroups. In a small number of patients with the triple feature of bilateral recurrent calcium phosphate stones, Konnak and coworkers (30) found that all of them had defective renal acidification. Although these individuals may have acquired incomplete dRTA, they can also be heterozygous carriers of candidate genes. However, no genotypic data were presented in any of these studies mentioned above. In fact, based on the supposition, albeit unverified, that heterozygous carriers of the dRTA candidate genes are completely normal individuals, genetic causes for subtle defects in acidification in stone formers were likely never examined. If heterozygous careers of mutant candidate genes of dRTA harbor subclinical defects that elude routine clinical chemistry and confer a propensity for disease rather causing disease, then one will not succeed in recognizing inheritance patterns at all. There is a need for database of sequence variance in candidate genes for dRTA in the general stone-forming population.

GRANTS

The authors are supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-DK-081523, R01-AI-041612, R01-HL-72034, the O'Brien Kidney Research Center (NIH Grant P30-DK-079328), the Simmons Family Foundation, and the Charles Pak and Donald Seldin Endowment for Metabolic Research. D. G. Fuster was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (31003A_135503 and NCCR Kidney.CH) and by a Medical Research Position Award of the Foundation Prof. Dr. Max Cloëtta.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. conception and design of research; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., C.G., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. performed experiments; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., C.G., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. analyzed data; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. interpreted results of experiments; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. prepared figures; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. drafted manuscript; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. edited and revised manuscript; J.Z., D.G.F., M.A.C., H.Q., X.-S.X., and O.W.M. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr. Margaret Pearle (Department of Urology) for obtaining the kidney biopsy and the Mineral Metabolism Clinical Laboratory staff at the Pak Center at University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center for processing of the patient samples.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arampatzis S, Ropke-Rieben B, Lippuner K, Hess B. Prevalence and densitometric characteristics of incomplete distal renal tubular acidosis in men with recurrent calcium nephrolithiasis. Urol Res 40: 53–59, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Backman U, Danielson BG, Johansson G, Ljunghall S, Wikstrom B. Incidence and clinical importance of renal tubular defects in recurrent renal stone formers. Nephron 25: 96–101, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bajaj G, Quan A. Renal tubular acidosis and deafness: report of a large family. Am J Kidney Dis 27: 880–882, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner RJ, Spring DB, Sebastian A, McSherry EM, Genant HK, Palubinskas AJ, Morris RC, Jr. Incidence of radiographically evident bone disease, nephrocalcinosis, and nephrolithiasis in various types of renal tubular acidosis. N Engl J Med 307: 217–221, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown D, Paunescu TG, Breton S, Marshansky V. Regulation of the V-ATPase in kidney epithelial cells: dual role in acid-base homeostasis and vesicle trafficking. J Exp Biol 212: 1762–1772, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruce LJ, Cope DL, Jones GK, Schofield AE, Burley M, Povey S, Unwin RJ, Wrong O, Tanner MJ. Familial distal renal tubular acidosis is associated with mutations in the red cell anion exchanger (Band 3, AE1) gene. J Clin Invest 100: 1693–1707, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruce LJ, Wrong O, Toye AM, Young MT, Ogle G, Ismail Z, Sinha AK, McMaster P, Hwaihwanje I, Nash GB, Hart S, Lavu E, Palmer R, Othman A, Unwin RJ, Tanner MJ. Band 3 mutations, renal tubular acidosis and South-East Asian ovalocytosis in Malaysia and Papua New Guinea: loss of up to 95% band 3 transport in red cells. Biochem J 350: 41–51, 2000 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckalew VM, Jr. Nephrolithiasis in renal tubular acidosis. J Urol 141: 731–737, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckalew VM, Jr., McCurdy DK, Ludwig GD, Chaykin LB, Elkinton JR. Incomplete renal tubular acidosis. Physiologic studies in three patients with a defect in lowering urine pH. Am J Med 45: 32–42, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chafe L, Gault MH. First morning urine pH in the diagnosis of renal tubular acidosis with nephrolithiasis. Clin Nephrol 41: 159–162, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheidde L, Vieira TC, Lima PR, Saad ST, Heilberg IP. A novel mutation in the anion exchanger 1 gene is associated with familial distal renal tubular acidosis and nephrocalcinosis. Pediatrics 112: 1361–1367, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cintron-Nadal E, Lespier LE, Roman-Miranda A, Martinez-Maldonado M. Renal acidifying ability in subjects with recurrent stone formation. J Urol 118: 704–706, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordat E, Kittanakom S, Yenchitsomanus PT, Li J, Du K, Lukacs GL, Reithmeier RA. Dominant and recessive distal renal tubular acidosis mutations of kidney anion exchanger 1 induce distinct trafficking defects in MDCK cells. Traffic 7: 117–128, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crider BP, Xie XS, Stone DK. Bafilomycin inhibits proton flow through the H+ channel of vacuolar proton pumps. J Biol Chem 269: 17379–17381, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D'Angelo A, Pagano F, Ossi E, Lupo A, Valvo E, Messa P, Tessitore N, Maschio G. Renal tubular defects in recurring bilateral nephrolithiasis. Clin Nephrol 6: 352–360, 1976 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dedmon RE, Wrong O. The excretion of organic anion in renal tubular acidosis with particular reference to citrate. Clin Sci 22: 19–32, 1962 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DuBose TD, Jr., Caflisch CR. Validation of the difference in urine and blood carbon dioxide tension during bicarbonate loading as an index of distal nephron acidification in experimental models of distal renal tubular acidosis. J Clin Invest 75: 1116–1123, 1985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forgac M. Vacuolar ATPases: rotary proton pumps in physiology and pathophysiology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 917–929, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fry AC, Karet FE. Inherited renal acidoses. Physiology (Bethesda) 22: 202–211, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuster DG, Zhang J, Xie XS, Moe OW. A novel truncation mutation of the V-ATPase B1 subunit and analysis of how point mutants of B1 cause pump dysfunction. Kidney Int 73: 1151–1158, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fuster DG, Zhang J, Xie XS, Moe OW. The vacuolar-ATPase B1 subunit in distal tubular acidosis: novel mutations and mechanisms for dysfunction. Kidney Int 73: 1151–1158, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gault MH, Chafe LL, Morgan JM, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD, Walsh EA, Prabhakaran VM, Dow D, Colpitts A. Comparison of patients with idiopathic calcium phosphate and calcium oxalate stones. Medicine (Baltimore) 70: 345–359, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu PY, Roth DE, Skaggs LA, Venta PJ, Tashian RE, Guibaud P, Sly WS. A splice junction mutation in intron 2 of the carbonic anhydrase II gene of osteopetrosis patients from Arabic countries. Hum Mutat 1: 288–292, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inoue T, Wang Y, Jefferies K, Qi J, Hinton A, Forgac M. Structure and regulation of the V-ATPases. J Bioenerg Biomembr 37: 393–398, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarolim P, Shayakul C, Prabakaran D, Jiang L, Stuart-Tilley A, Rubin HL, Simova S, Zavadil J, Herrin JT, Brouillette J, Somers MJ, Seemanova E, Brugnara C, Guay-Woodford LM, Alper SL. Autosomal dominant distal renal tubular acidosis is associated in three families with heterozygosity for the R589H mutation in the AE1 (band 3) Cl−/HCO3− exchanger. J Biol Chem 273: 6380–6388, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kane PM, Parra KJ. Assembly and regulation of the yeast vacuolar H+-ATPase. J Exp Biol 203: 81–87, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karet FE. Physiological and metabolic implications of V-ATPase isoforms in the kidney. J Bioenerg Biomembr 37: 425–429, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karet FE, Finberg KE, Nelson RD, Nayir A, Mocan H, Sanjad SA, Rodriguez-Soriano J, Santos F, Cremers CW, Di Pietro A, Hoffbrand BI, Winiarski J, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Dusunsel R, Goodyer P, Hulton SA, Wu DK, Skvorak AB, Morton CC, Cunningham MJ, Jha V, Lifton RP. Mutations in the gene encoding B1 subunit of H+-ATPase cause renal tubular acidosis with sensorineural deafness. Nat Genet 21: 84–90, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karet FE, Gainza FJ, Gyory AZ, Unwin RJ, Wrong O, Tanner MJ, Nayir A, Alpay H, Santos F, Hulton SA, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Cunningham MJ, di Pietro A, Walker WG, Lifton RP. Mutations in the chloride-bicarbonate exchanger gene AE1 cause autosomal dominant but not autosomal recessive distal renal tubular acidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 6337–6342, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Konnak JW, Kogan BA, Lau K. Renal calculi associated with incomplete distal renal tubular acidosis. J Urol 128: 900–902, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laing CM, Unwin RJ. Renal tubular acidosis. J Nephrol 19, Suppl 9: S46–S52, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ma J, Tasch JE, Tao T, Zhao J, Xie J, Drumm ML, Davis PB. Phosphorylation-dependent block of cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator chloride channel by exogenous R domain protein. J Biol Chem 271: 7351–7356, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maalouf NM, Cameron MA, Moe OW, Adams-Huet B, Sakhaee K. Low urine pH: a novel feature of the metabolic syndrome. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 883–888, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Megevand M, Favre H. Distal renal tubular dysfunction: a common feature in calcium stone formers. Eur J Clin Invest 14: 456–461, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mumberg D, Muller R, Funk M. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene 156: 119–122, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakagawa Y, Carvalho M, Malasit P, Nimmannit S, Sritippaywan S, Vasuvattakul S, Chutipongtanate S, Chaowagul V, Nilwarangkur S. Kidney stone inhibitors in patients with renal stones and endemic renal tubular acidosis in northeast Thailand. Urol Res 32: 112–116, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nordin BE, Smith DA. Citric acid excretion in renal stone disease and in renal tubular acidosis. Br J Urol 35: 438–444, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nutahara K, Higashihara E, Ishiii Y, Niijima T. Renal hypercalciuria and acidification defect in kidney stone patients. J Urol 141: 813–818, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osther PJ. Effect of acute acid loading on acid-base and calcium metabolism. Scand J Urol Nephrol 40: 35–44, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Osther PJ, Bollerslev J, Hansen AB, Engel K, Kildeberg P. Pathophysiology of incomplete renal tubular acidosis in recurrent renal stone formers: evidence of disturbed calcium, bone and citrate metabolism. Urol Res 21: 169–173, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osther PJ, Hansen AB, Rohl HF. Distal renal tubular acidosis in recurrent renal stone formers. Dan Med Bull 36: 492–493, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Osther PJ, Hansen AB, Rohl HF. Renal acidification defects in medullary sponge kidney. Br J Urol 61: 392–394, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Osther PJ, Hansen AB, Rohl HF. Renal acidification defects in patients with their first renal stone episode. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 110: 275–278, 1988 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osther PJ, Hansen AB, Rohl HF. Screening renal stone formers for distal renal tubular acidosis. Br J Urol 63: 581–583, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pak CY, Poindexter JR, Adams-Huet B, Pearle MS. Predictive value of kidney stone composition in the detection of metabolic abnormalities. Am J Med 115: 26–32, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pak CY, Poindexter JR, Peterson RD, Heller HJ. Biochemical and physicochemical presentations of patients with brushite stones. J Urol 171: 1046–1049, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng SB. Nucleotide labeling and reconstitution of the recombinant 58-kDa subunit of the vacuolar proton-translocating ATPase. J Biol Chem 270: 16926–16931, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Petschnigg J, Moe OW, Stagljar I. Using yeast as a model to study membrane proteins. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20: 425–432, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Quilty JA, Cordat E, Reithmeier RA. Impaired trafficking of human kidney anion exchanger (kAE1) caused by hetero-oligomer formation with a truncated mutant associated with distal renal tubular acidosis. Biochem J 368: 895–903, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Quilty JA, Li J, Reithmeier RA. Impaired trafficking of distal renal tubular acidosis mutants of the human kidney anion exchanger kAE1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F810–F820, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sakhaee K, Adams-Huet B, Moe OW, Pak CY. Pathophysiologic basis for normouricosuric uric acid nephrolithiasis. Kidney Int 62: 971–979, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schiestl RH, Gietz RD. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet 16: 339–346, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shah GN, Bonapace G, Hu PY, Strisciuglio P, Sly WS. Carbonic anhydrase II deficiency syndrome (osteopetrosis with renal tubular acidosis and brain calcification): novel mutations in CA2 identified by direct sequencing expand the opportunity for genotype-phenotype correlation. Hum Mutat 24: 272, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh PP, Pendse AK, Ahmed A, Ramavataram DV, Rajpurohit SK. A study of recurrent stone formers with special reference to renal tubular acidosis. Urol Res 23: 201–203, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sly WS, Hewett-Emmett D, Whyte MP, Yu YS, Tashian RE. Carbonic anhydrase II deficiency identified as the primary defect in the autosomal recessive syndrome of osteopetrosis with renal tubular acidosis and cerebral calcification. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 80: 2752–2756, 1983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith AN, Skaug J, Choate KA, Nayir A, Bakkaloglu A, Ozen S, Hulton SA, Sanjad SA, Al-Sabban EA, Lifton RP, Scherer SW, Karet FE. Mutations in ATP6N1B, encoding a new kidney vacuolar proton pump 116-kD subunit, cause recessive distal renal tubular acidosis with preserved hearing. Nat Genet 26: 71–75, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sritippayawan S, Kirdpon S, Vasuvattakul S, Wasanawatana S, Susaengrat W, Waiyawuth W, Nimmannit S, Malasit P, Yenchitsomanus PT. A de novo R589C mutation of anion exchanger 1 causing distal renal tubular acidosis. Pediatr Nephrol 18: 644–648, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stehberger PA, Schulz N, Finberg KE, Karet FE, Giebisch G, Lifton RP, Geibel JP, Wagner CA. Localization and regulation of the ATP6V0A4 (a4) vacuolar H+-ATPase subunit defective in an inherited form of distal renal tubular acidosis. J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3027–3038, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stitchantrakul W, Kochakarn W, Ruangraksa C, Domrongkitchaiporn S. Urinary risk factors for recurrent calcium stone formation in Thai stone formers. J Med Assoc Thai 90: 688–698, 2007 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stover EH, Borthwick KJ, Bavalia C, Eady N, Fritz DM, Rungroj N, Giersch AB, Morton CC, Axon PR, Akil I, Al-Sabban EA, Baguley DM, Bianca S, Bakkaloglu A, Bircan Z, Chauveau D, Clermont MJ, Guala A, Hulton SA, Kroes H, Li Volti G, Mir S, Mocan H, Nayir A, Ozen S, Rodriguez Soriano J, Sanjad SA, Tasic V, Taylor CM, Topaloglu R, Smith AN, Karet FE. Novel ATP6V1B1 and ATP6V0A4 mutations in autosomal recessive distal renal tubular acidosis with new evidence for hearing loss. J Med Genet 39: 796–803, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Szendroi Z, Simon K, Kiss L. Renal tubular acidosis: its types and role in renal calculosis. Int Urol Nephrol 14: 247–257, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tam SC, Goldstein MB, Stinebaugh BJ, Chen CB, Gougoux A, Halperin ML. Studies on the regulation of hydrogen ion secretion in the collecting duct in vivo: evaluation of factors that influence the urine minus blood Pco2 difference. Kidney Int 20: 636–642, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tessitore N, Ortalda V, Fabris A, D'Angelo A, Rugiu C, Oldrizzi L, Lupo A, Valvo E, Gammaro L, Loschiavo C.et al. Renal acidification defects in patients with recurrent calcium nephrolithiasis. Nephron 41: 325–332, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Toye AM, Banting G, Tanner MJ. Regions of human kidney anion exchanger 1 (kAE1) required for basolateral targeting of kAE1 in polarised kidney cells: mis-targeting explains dominant renal tubular acidosis (dRTA). J Cell Sci 117: 1399–1410, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Uribarri J, Douyon H, Oh MS. A re-evaluation of the urinary parameters of acid production and excretion in patients with chronic renal acidosis. Kidney Int 47: 624–627, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van den Berg CJ, Harrington TM, Bunch TW, Pierides AM. Treatment of renal lithiasis associated with renal tubular acidosis. Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc 20: 473–476, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vargas-Poussou R, Houillier P, Le Pottier N, Strompf L, Loirat C, Baudouin V, Macher MA, Dechaux M, Ulinski T, Nobili F, Eckart P, Novo R, Cailliez M, Salomon R, Nivet H, Cochat P, Tack I, Fargeot A, Bouissou F, Kesler GR, Lorotte S, Godefroid N, Layet V, Morin G, Jeunemaitre X, Blanchard A. Genetic investigation of autosomal recessive distal renal tubular acidosis: evidence for early sensorineural hearing loss associated with mutations in the ATP6V0A4 gene. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1437–1443, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wagner CA, Devuyst O, Bourgeois S, Mohebbi N. Regulated acid-base transport in the collecting duct. Pflügers Arch 458: 137–156, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weber S, Soergel M, Jeck N, Konrad M. Atypical distal renal tubular acidosis confirmed by mutation analysis. Pediatr Nephrol 15: 201–204, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wikstrom B, Backman U, Danielson BG, Fellstrom B, Johansson G, Ljunghall S, Wide L. Phosphate metabolism in renal stone formers. (II): Relation to renal tubular functions and calcium metabolism. Scand J Urol Nephrol Suppl 61: 1–26, 1981 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wrong O, Davies HE. The excretion of acid in renal disease. Q J Med 28: 259–313, 1959 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xie XS, Stone DK, Racker E. Proton pump of clathrin-coated vesicles. Methods Enzymol 157: 634–646, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yang Q, Li G, Singh SK, Alexander EA, Schwartz JH. Vacuolar H+-ATPase B1 subunit mutations that cause inherited distal renal tubular acidosis affect proton pump assembly and trafficking in inner medullary collecting duct cells. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1858–1866, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]