Summary

Experience-dependent plasticity in the adult brain has clinical potential for functional rehabilitation following central and peripheral nerve injuries. Here, plasticity induced by unilateral infraorbital (IO) nerve resection in four week-old rats was mapped using MRI and synaptic mechanisms were elucidated by slice electrophysiology. Functional MRI demonstrates a cortical potentiation compared to thalamus two weeks after IO nerve resection. Tracing thalamocortical (TC) projections with manganese-enhanced MRI revealed circuit changes in the spared layer 4 (L4) barrel cortex. Brain slice electrophysiology revealed TC input strengthening onto L4 stellate cells due to an increase in postsynaptic strength and the number of functional synapses. This work shows that the TC input is a site for robust plasticity after the end of the previously defined critical period for this input. Thus, TC inputs may represent a major site for adult plasticity in contrast to the consensus that adult plasticity mainly occurs at cortico-cortical connections.

Introduction

Experience is a potent force that shapes brain circuits and function. Elucidating how sensory experience influences cortical sensory representations has been at the forefront of understanding the mechanisms of experience-driven cortical plasticity (Buonomano and Merzenich, 1998; Fox, 2009; Karmarkar and Dan, 2006; Majewska and Sur, 2006; Ramachandran, 2005). Such plasticity is greatest during postnatal development during certain ‘critical periods’, but is also extensively documented in the adult brain including human cortex (Hensch, 2004; Hooks and Chen, 2007; Hummel and Cohen, 2005; Knudsen, 2004). Adult plasticity can be induced in response to deprivation of sensory input, for example due to peripheral nerve injury or amputation (Kaas, 1991; Kaas and Collins, 2003; Wall et al., 2002). The site(s) and mechanism(s) of adult cortical plasticity are not well characterized. The relative contributions of cortical-cortical synaptic changes across the cortical layers or the extent of changes in ascending thalamocortical projections remains unsettled (Cooke and Bear, 2010; Fox et al., 2002; Jones, 2000; Kaas et al., 2008).

Recently, there has been growing interest in using MRI to map plasticity in the adult rodent brain (Dijkhuizen et al., 2001; Pelled et al., 2009; Pelled et al., 2007b; van Meer et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2010). Blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional MRI (BOLD-fMRI) techniques have been extensively used in humans and animals to investigate changes in brain function (Cramer et al., 2011). However, the underlying neurovascular coupling mechanism of BOLD-fMRI limits its functional mapping specificity (Logothetis et al., 2001; Ugurbil et al., 2003). Manganese-enhanced MRI (MEMRI) can provide high-resolution MRI for in vivo tracing of neuronal circuits (Bilgen et al., 2006; Canals et al., 2008; Murayama et al., 2006; Pautler et al., 1998; Van der Linden et al., 2002). Manganese (Mn2+) is calcium analog, which can mimic calcium entry into neurons, allow activity dependent Mn-accumulation to make MRI map of activation (Lin and Koretsky, 1997; Yu et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2008). Furthermore, Mn2+ crosses synapses and may report synaptic strength (Narita et al., 1990). Indeed, a few studies have attributed changes in MEMRI signal to synaptic plasticity (Pelled et al., 2007a; Van der Linden et al., 2009; Van der Linden et al., 2002; van der Zijden et al., 2008; van Meer et al., 2010; Yu et al., 2007). Recently, it has been shown that MEMRI can track neuronal circuits with laminar specificity, opening up the possibility of identifying sites of plasticity with high resolution (Tucciarone et al., 2009).

In the present study we use both BOLD-fMRI and MEMRI combined with subsequent brain slice electrophysiology to identify a location and mechanism of plasticity in a model of peripheral deprivation of sensory input from the whiskers in 4-6 week old rats. The cortical representation of the whiskers is in the barrel cortex, which contains clusters of cells termed ‘barrels’ that are the anatomical correlates of the whisker receptive fields (Woolsey and Van der Loos, 1970). Both the development and adult organization of the barrel cortex is highly sensitive to sensory experience (Daw et al., 2007b; Feldman and Brecht, 2005; Fox, 2002; Van der Loos and Woolsey, 1973). For adult barrel cortex, the prevailing view is that plasticity is due to changes in cortico-cortical connections with little or no contribution from thalamocortical or subcortical mechanisms. Rather, thalamocortical and subcortical plasticity is restricted to well defined ‘critical periods’ early in life.

In the present study, post critical period plasticity of the TC input from the spared whiskers was identified as a prominent mechanism in six week-old rats two weeks after unilateral infraorbital (IO) nerve resection. The TC plasticity was identified using BOLD-fMRI and MEMRI techniques combined with subsequent analysis of the synaptic mechanisms using brain slice electrophysiology. The results provide clear evidence that the TC input to L4 is strengthened even though peripheral nerve resection was performed after the end of TC critical period. Furthermore, this work shows for the first time the ability for MRI to guide patch clamp electrophysiology to identify the laminar specific site(s) of modification underlying plasticity in the brain.

Results

BOLD-fMRI mapping of plasticity

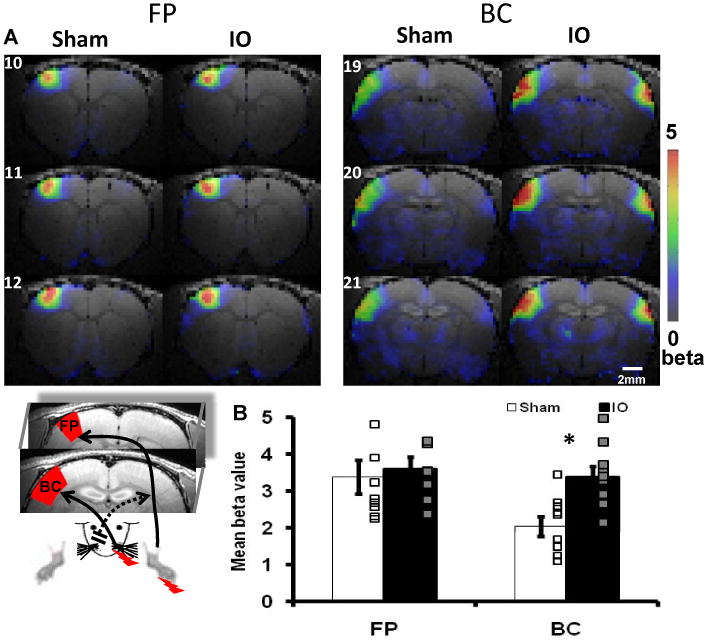

Six week-old rats that had undergone unilateral IO nerve resection (‘IO rats’) or sham surgery (‘sham rats’) at four weeks of age were imaged by MRI. To assess plasticity of circuits activated by the spared input, the BOLD response elicited by electrical stimulation of the intact whisker pad was measured. In addition, the right forepaw was also stimulated simultaneously in the same rats so that the BOLD response in the forepaw S1 (FP) area could be used as an internal control for the plasticity-induced changes in the barrel cortex (Figure 1 inset). To identify specific regions we co-registered the MRI with a brain atlas (Supplemental Figures 1A-C; also see Methods). Along the whisker-barrel pathway, increased BOLD responses in IO rats compared to sham were detected in the contralateral S1 barrel cortex (Figure 1). There was also an increased BOLD response in ipsilateral S1 barrel cortex. In contrast, the BOLD responses elicited by right forepaw stimulation were not different between the two experimental groups. Thus, unilateral IO nerve resection in four week old rats causes a specific increase in the BOLD response to the activation of the spared input in the barrel cortex.

Figure 1.

IO nerve resection causes bilaterally increased BOLD responses in the barrel cortex. (A) The averaged beta maps of three consecutive coronal slices cover forepaw (FP, 10-12) and barrel cortex (BC, 19-21) S1 areas. The stimulation was delivered to the right forepaw and the spared whisker pad (inset, FP and BC ROIs in red contour defined by atlas). (B) Quantitative group analysis showed significantly increase BOLD signal in the contralateral BC of the IO rats (BOLD signal changes were defined as mean beta value (Supplementary note 2); Sham: n=9, IO: n=9; * means p<0.01, bar graph shows mean±SEM).

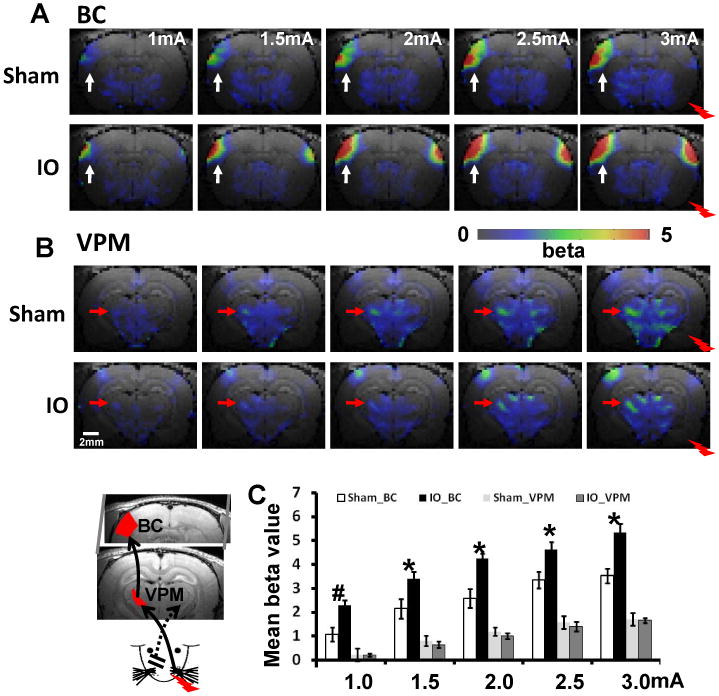

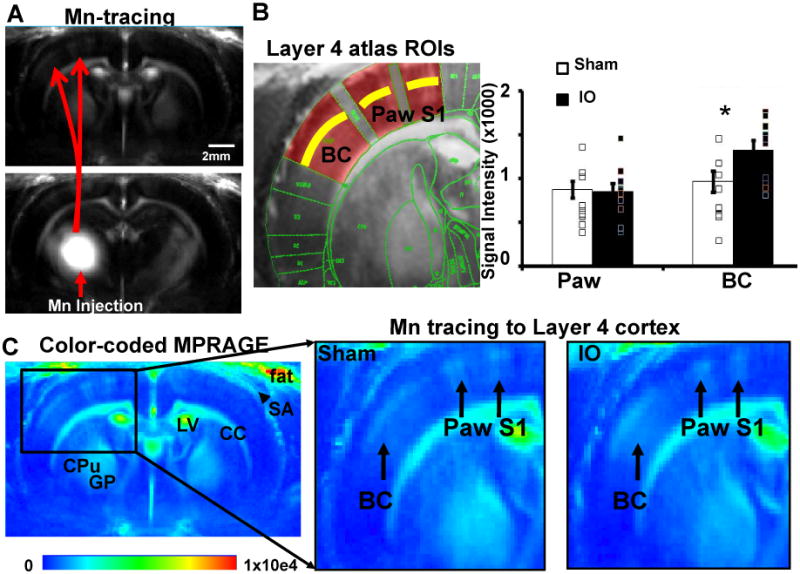

To determine if there was any change in the relation between thalamic and cortical fMRI response, functional changes in the ventral posteriomedial nucleus (VPM) of thalamus, which receives ascending input from the whiskers, were analyzed (Figure 2, inset). Stimulation of the spared input elicited a BOLD response in the contralateral VPM as expected (Supplementary Figure 1D). Five increasing stimulus intensities were used and the responses in VPM between IO and sham rats were compared (see Methods for details). At all intensities the VPM BOLD response was not different between the two groups; however, in the same animals the S1 barrel cortex BOLD responses were larger in IO rats compared to sham (Figure 2, Supplementary Figure 2, Supplementary Table 1: e.g. at 3.0mA, the BOLD signal changes of BC in the IO group is increased 50% compared to sham). When the VPM BOLD response was plotted against the S1 BOLD response to produce an input-output plot, there was an increased slope in IO rats compared to sham, showing a 60% cortical potentiation in response to activation of spared input (Figure 3). To confirm the increased neuronal responses in the barrel cortex as shown by BOLD-fMRI, in vivo electrophysiological recordings were performed to analyze whisker pad stimulation-evoked potentials in both L4 barrel cortex and VPM across a range of stimulation intensities (Supplementary note 1). Consistent with the BOLD-fMRI data, there was no difference in the evoked potentials in VPM between the two groups; however, in the same animals the evoked potentials in L4-barrel cortex were larger in IO rats compared to sham (Supplementary table 2: e.g. at 3.0mA, the evoked potential amplitude in L4-BC in the IO group is increased 36% compared to sham). By measuring the slope of the input-out relationship (L4-BC vs. VPM), we observed a significantly steeper slope in IO rats compared to sham, showing a 49% cortical potentiation in response to stimulation of the spared whisker pad (Supplementary Figure 3). This result demonstrates that the plasticity observed in spared cortex is very likely due to cortical modification and involves TC inputs.

Figure 2.

BOLD responses in BC and VPM increase corresponding to the increased stimulation intensities. The schematic drawing of whisker-barrel TC circuit is shown in the inset at the left-bottom corner. The averaged beta maps of barrel cortex (BC) (A, white arrow) and VPM (B, red arrow) at five stimulation intensities from 1mA to 3mA. (C) The averaged mean beta values of BC and VPM ROIs (defined by brain atlas shown in the inset; Sham: n=8 (3 at 1.0mA); IO: n=10 (4 at 1.0mA); # means p<0.02; * means p<0.01, bar graph shows mean±SEM). The averaged fMRI time courses for each ROI were shown in the Supplementary Fig 2.

Figure 3.

Potentiation of cortical BOLD response in BC versus VPM. (A)The scatter plot of the BOLD response in BC and VPM ROIs of individual animals at different stimulation intensity (Sham, open circle; IO, solid circle) with linear fitting (Sham, dotted line; IO, solid line) (B) The slope of BC/VPM BOLD responses in the IO group compared to the Sham group (Sham: 2.15±0.34 n=8; IO: 3.45±0.85, n=10; * means p<0.001, bar graph shows mean±SEM).

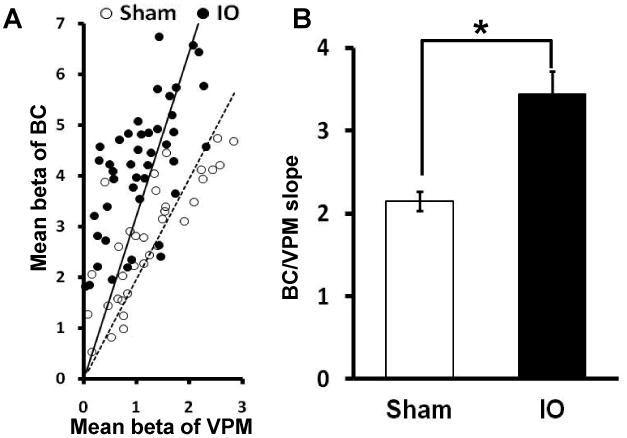

MEMRI identifies the layer 4 barrel cortex as a site of cortical plasticity

BOLD-fMRI identified S1 contralateral barrel cortex as a prominent site of plasticity in the response to spared input activation. To investigate the mechanisms at this site of plasticity, MEMRI were used to determine if the plasticity could be explained by strengthening of the TC input. Numerous studies provide evidence that changes in Mn2+ transport reflects plasticity (Pelled et al., 2007a; Van der Linden et al., 2009; Van der Linden et al., 2002; van der Zijden et al., 2008; van Meer et al., 2010), and laminar resolution tracing with MEMRI has been demonstrated (Tucciarone et al., 2009). Mn2+ was injected into dorsal thalamus encompassing VPM (Supplementary Figure 4) to determine if the spared TC input to barrel cortex is modified by unilateral IO nerve resection. A prominent MEMRI signal was observed in L4 of barrel cortex and the intensity of this signal was greater in IO rats compared to sham (Figure 4). In the same rats, the Mn2+-enhanced signal in L4 of the paw representation was not different between the two groups. In addition, no difference in Mn2+ was detected at the injection sites between VPM and ventral posteriomedial nucleus (VPL) in either group (Supplementary Figure 4). Therefore, the MEMRI data indicate that IO nerve resection may increase TC input strength to L4 specifically in barrel cortex for the spared input.

Figure 4.

MEMRI reveals the strengthening of the TC input to layer 4 barrel cortex (BC). (A) Mn tracing from Mn injection site in the dorsal thalamus (VPM+VPL, detail in supplementary figure 3) to the ipsilateral S1 including barrel cortex and paw S1 area. (B) Left: the atlas overlapped MPRAGE images to define the Layer 4 ROIs in the BC and paw S1 areas. Right: the analysis of MEMRI signal in the L4 of the BC and paw S1 area in IO and Sham groups (Sham: n=10; IO: n=9; * means p<0.03, bar graph shows mean±SEM). (C) Color-coded MPRAGE images from the sham and IO groups. Left: Mn-enhanced L4 lamina were only located at the same side as the Mn injection. Mn independent signal enhancement was shown in several brain regions in both hemispheres, such as, corpus callosum (CC), caudate putamen (CPu), globus pallidus (GP), lateral ventricle (LV) and in the subarachanoid area (SA, arrowhead) and the fat tissue outside the skull. Right: enlarged image to show the Mn-enhanced L4 lamina in both BC and paw S1 areas (black arrows), showing stronger Mn-enhanced signal in the BC L4 of IO rats than that of sham rats.

IO nerve resection causes an increase in thalamocortical input strength to layer 4 of spared barrel cortex

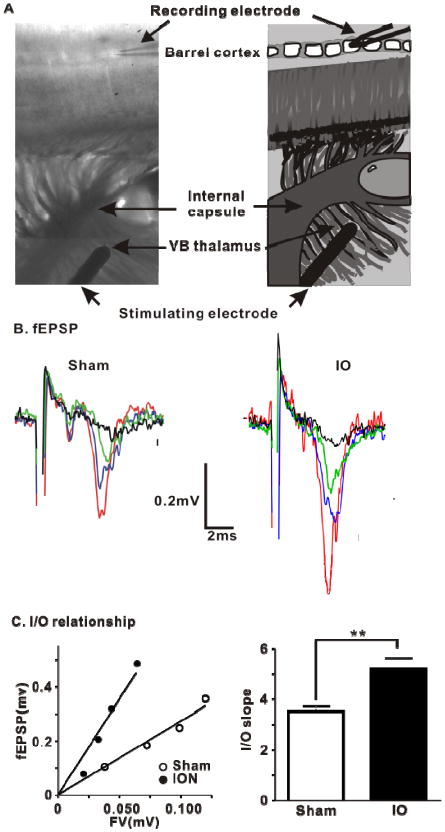

To investigate the underlying mechanism for the increased BOLD-fMRI and MEMRI signals in L4 barrel cortex, thalamocortical brain slices were prepared from six week old rats that had undergone either IO nerve resection or sham surgery at four weeks. The thalamocortical brain slice preparation allows TC input to barrel cortex to be selectively activated by extracellular stimulation in VPM and resulting synaptic responses to be monitored with extracellular or patch-clamp recordings (Agmon and Connors, 1991; Crair and Malenka, 1995; Isaac et al., 1997). Extracellular field potential recordings were made to measure TC fEPSPs evoked by electrical stimulation in VPM. TC inputs are glutamatergic, with the fEPSP mediated by AMPARs (Agmon and O'Dowd, 1992; Crair and Malenka, 1995; Kidd and Isaac, 1999; Lu et al., 2001). Consistent with this and previous work (Agmon and Connors, 1992; Crair and Malenka, 1995), the fEPSP was reversibly blocked by 10 μM NBQX, an AMPAR antagonist, or a Ca2+-free extracellular solution (Supplemental Figure 5). These manipulations did not block the small early downward deflection confirming that this small deflection is a pre-synaptic fiber volley.

The strength of the TC input to layer 4 (contralateral to the intact whisker-pad) in slices prepared from sham or IO rats was compared by measuring the fEPSP: fiber volley (FV) ratio at different stimulus intensities (Figure 5). This input/output (I/O) relationship was significantly steeper in slices from IO rats compared to sham, demonstrating an increase in TC input strength in the spared input side following IO nerve resection. There was a 47 % increase in TC synaptic strength in the IO rats compared to sham. To examine whether intracortical (IC) synapses in L4 barrel cortex are strengthened following IO nerve resection, in a separate set of experiments we measured TC fEPSPs and IC fEPSPs in layer 4 (Supplementary Fig 6). We confirmed the increase in the input/output relationship for TC fEPSPs, but found no increase in the input/output relationship for IC fEPSPs in slices from IO rats. Thus, intracortical synaptic strength in layer 4 is not increased in spared barrel cortex in IO rats, indicating strengthening of TC synapses.

Figure 5.

IO nerve resection causes an increase in TC fEPSPs in spared layer 4 barrel cortex. (A) Thalamocortical brain slice extracellular recording setup and the corresponding diagram. (B) Representative superimposed traces of fEPSPs from TC slices from example experiments at four increasing stimulus intensities. (C) Left panel, scatter plot of the I/O relationship corresponding to the recorded fEPSPs in (B). Sham, y = 2.87x, r2= 0.80, open circles; IO, y=6.59x, r2= 0.82, filled circles. Right panel, Averaged slope of I/O relationship for Sham and IO group (Sham: 3.52 ± 0.20, n=20; ION: 4.96 ± 0.04, n=13; ** means P< 0.01, bar graph shows mean±SEM).

No change in feedforward inhibition or short-term plasticity onto L4 stellate cells following IO nerve resection

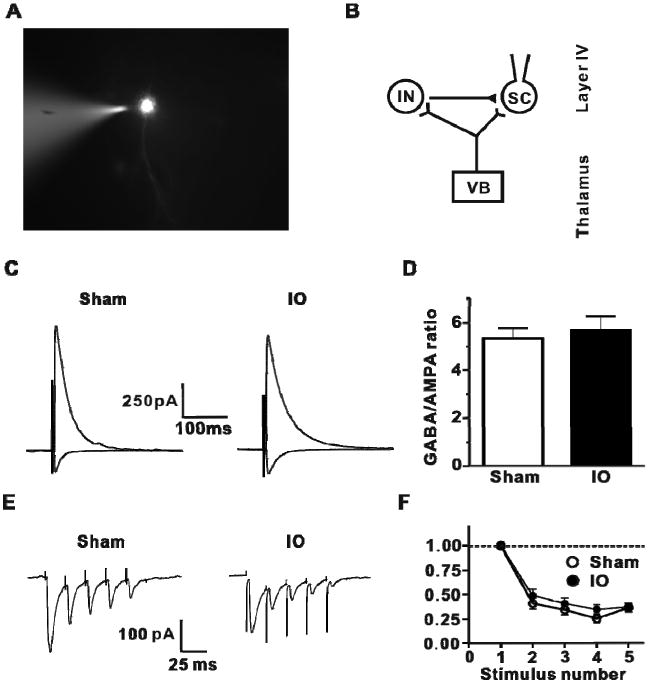

The mechanism(s) underlying the increase in the TC fEPSP in the spared barrel cortex were studied with patch-clamp recordings. GABAergic feedforward inhibition in L4 barrel cortex is strongly engaged by TC afferent activity and serves to regulate co-incidence detection, truncate the EPSP and limit spike output in L4 (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Cruikshank et al., 2007; Daw et al., 2007a; Gabernet et al., 2005; Porter et al., 2001). A change in the engagement of feed forward inhibition could contribute to the change of the TC fEPSP observed in the IO rats. Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings from L4 stellate cells were performed to measure the feed forward inhibition and feed forward excitation onto the same stellate cells using established techniques (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Daw et al., 2007a). The disynaptic feed forward GABAA receptor-mediated IPSC elicited by VPM stimulation was measured at a holding potential of 0 mV (the reversal potential for the EPSC), and in the same cell in response to the same VPM stimulation the monosynaptic AMPA receptor-mediated TC EPSC was recorded at -70 mV (the GABAA receptor reversal potential) (Figure 6B,C). This ratio of the IPSC:EPSC (‘GABA:AMPA ratio’) was unchanged between the IO and sham groups (Figure 6D). Thus, feed forward inhibition as a ratio of feed forward excitation in L4 is unaffected by IO nerve resection indicating that feed forward inhibition scales with the increased feed forward excitatory drive in spared L4 barrel cortex.

Figure 6.

IO nerve resection has no effect on feedforward inhibition or short-term plasticity at TC inputs to layer 4. (A) Patch clamp recording on a L4 stellate cell. (B) The diagram of TC feedforward monosynaptic excitatory and feedforward disynaptic inhibition pathway. (C) Representative traces of TC GABAA receptor-mediated IPSC (average of 5 sweeps; outward current) at 0 mV holding potential and TC EPSC (average of 5 sweeps; inward current) at -70 mV in L4 stellate cells from Sham and IO nerve resection groups. (D) Analysis of GABAA receptor-mediated IPSC amplitude to AMPAR-mediated EPSC ratio for all cells (Sham: 5.34 ± 0.31, n=10, open bars; IO: 5.82 ± 0.46, n=9, filled bars, bar graph shows mean±SEM). (E) Representative traces of train-stimulation evoked EPSCs (50Hz; average of 10 trials) for two groups. (F) Analysis of EPSC amplitude during trains (normalize to first EPSC in train) for both groups (Sham n = 7, IO n = 9)

The change in the TC input to L4 in IO rats could be due to increases in transmitter release probability (Pr), and/or the number of functional synaptic contacts (n) and/or their quantal size (q). To address the first possibility, short-term plasticity of the TC EPSC in L4 stellate cells was measured. As previously reported, TC inputs to L4 barrel cortex are depressing (e.g. (Castro-Alamancos, 2004; Gil et al., 1999; Kidd et al., 2002), and a brief train of VPM stimulation at 50 Hz causes a short-term depression of TC EPSCs (Figure 6E). This short term plasticity was not different between IO and sham groups (Figure 6F), indicating that presynaptic release probability of glutamate at TC inputs is not altered by IO nerve resection.

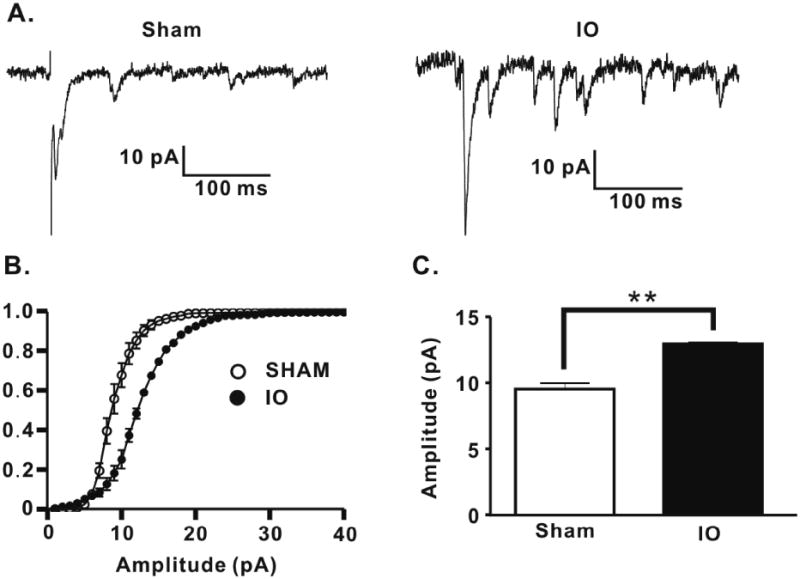

IO nerve resection causes an increase of quantal amplitude and number of functional contacts at the spared TC input to L4 stellate cells

To determine if a postsynaptic modification contributed to the increased TC synaptic strength onto L4 stellate cells in IO rats, the quantal amplitude of AMPAR-mediated TC EPSCs was measured. Substitution of Ca2+ with Sr2+ in the extracellular medium desynchronizes presynaptic transmitter release producing a barrage of evoked miniature EPSCs after afferent stimulation (Goda and Stevens, 1994). This approach has been used to assay changes in quantal amplitude at the TC input to L4 barrel cortex (Bannister et al., 2005; Gil et al., 1999; Lu et al., 2003). Sr-evoked miniature EPSCs in response to VPM stimulation in L4 stellate cells exhibited an increase in amplitude in the IO rats compared to those in the sham group (Figure 7). In contrast to VPM stimulation-evoked miniature synaptic events, there was no difference in the quantal amplitudes of miniature EPSCs or IPSCs in L4 stellate cells, the majority of which result from transmission at intracortical L4-L4 connections ((Lefort et al., 2009); Supplementary Figure 7). Thus, a postsynaptic increase in quantal amplitude contributes to the increased synaptic strength and is specific to the TC input to L4 in IO rats.

Figure 7.

IO nerve resection causes an increase in quantal amplitude at TC inputs to layer 4 stellate cells. (A) Representative traces of Sr-evoked miniature EPSCs for both groups. (B) Averaged cumulative probability plot of Sr-evoked miniature EPSCs for all cells for both groups (Sham: n=7, open circles; IO: n=5, filled circles; Kolmogrov-Smirnov test, P<0.01). (C) Mean amplitude of Sr2+ -evoked miniature EPSCs for both groups (Sham: 9.35 ± 0.46, n=7; IO: 12.70 ± 0.29, n=5; ** p < 0.01, bar graph shows mean±SEM).

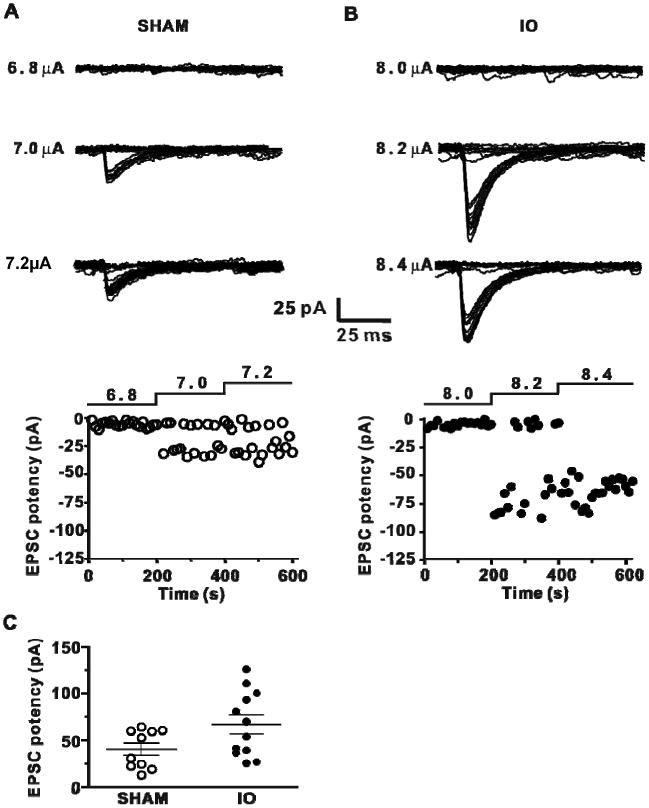

Another possible contribution to the change in TC synaptic strength is an increase in the number of functional synapses onto L4 stellate cells in the IO rats. To address this, a minimal-stimulation protocol was used to measure the postsynaptic response to activation of putative single TC axons e.g. (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Cruikshank et al., 2007; Dobrunz and Stevens, 1997; Gil et al., 1999; Isaac et al., 1997; Raastad et al., 1992; Stevens and Wang, 1995). To elicit putative single TC axon responses, VPM stimulus intensity was reduced until no synaptic responses were observed and then increased in small steps to find an intensity that stably elicited the smallest evoked response (Figure 8A, B). This minimal stimulation protocol revealed that in slices from IO rats the minimally-evoked EPSC amplitude (excluding failures; ‘potency’) was greater compared to that in slices from sham animals (Figure 8C). The potency for single fiber activation is dependent on quantal size and number of functional synaptic connections. There was a 37% increase in quantal size measured using Sr-evoked mEPSCs (Figure 7), whereas the potency increase was approx. 65 %, demonstrating that IO nerve resection additionally causes an increase in the number of functional TC synapses in L4. Taken together, the results show that IO nerve resection causes plasticity of the spared TC input by increasing both quantal amplitude and number of functional synapses.

Figure 8.

IO nerve resection causes an increase in minimal stimulation-evoked EPSCs in L4 stellate cells (A) Top superimposed individual traces (20 traces for each stimulus intensity) of EPSCs evoked by minimal stimulation at different intensities (indicated left) for an experiment from the Sham group. Bottom, amplitude of EPSCs plotted vs time with stimulus intensity indicated. (B) Same as A for IO nerve resection group. (C) Analysis of TC input potency (mean amplitude of successes ±SEM) for IO and Sham groups (Sham: -40.7 ± 6.5 pA, n=10; IO: -67.1 ± 10.0 pA, n=12; P< 0.05).

Discussion

The present study investigates the mechanisms and sites of plasticity induced by loss of whisker sensory input in 6 week-old rats using a combined MRI and slice electrophysiology approach. In contrast to the expectation that plasticity at this age is mediated by modification of cortico-cortical inputs, we found that a prominent plasticity of TC input to L4 underlies the robust increase in spared barrel cortex activation detectable by fMRI. This plasticity was due to a selective increase in quantal amplitude and number of functional synaptic contacts at the TC input to L4 stellate cells while maintaining excitatory/inhibitory balance. This combined MRI and slice electrophysiology approach therefore allows for an analysis of sites and mechanisms of plasticity, which could be broadly applied to many paradigms. The results show that TC inputs can mediate plasticity after the end of the previously defined critical period for this input.

Sensory deprivation leads to thalamocortical strengthening in IO rats

IO nerve resection was the sensory manipulation used to induce experience-dependent plasticity in barrel cortex. The IO nerve carries all sensory information from the whiskers, but does not contain motor afferents; therefore, this manipulation results in a complete loss of whisker-dependent sensory input with no loss of motor innervation to the whiskers. The increase in cortical BOLD-fMRI responses after two weeks of IO nerve resection in response to electrical stimulation of the spared whisker pad is likely due to increased cortical neuronal activity. Although there are a few examples in which BOLD-fMRI has not been associated with corresponding changes in neuronal activity (Maier et al., 2008; Sirotin and Das, 2009), a proportional increase of BOLD and neuronal signals has been observed in functional mapping studies across a variety of species including rodent, monkey, and human (Heeger et al., 2000; Logothetis et al., 2001; Ogawa et al., 2000; Rees et al., 2000) including for somatosensory cortex(Goloshevsky et al., 2008; Hyder et al., 2002). Indeed, in the present study in vivo electrophysiology directly demonstrates a potentiation of cortical responses in IO rats (Supplementary Fig 3, Supplementary Table 1, 2), which is consistent with a recent study, showing that two-week denervation of the rat forepaw led to a BOLD-fMRI increase in the spared forepaw S1 that was related to the increases in local field potential (Pelled et al., 2009).

Plasticity at multiple sites could potentially cause the altered BOLD-fMRI response in the barrel cortex of IO rats. The finding of increased activation in the barrel cortex versus changes in VPM activation points strongly to cortical site(s) of plasticity. The MEMRI data further indicate that L4 barrel cortex is a major site of plasticity and the slice electrophysiology shows that the TC input to L4, but not cortico-cortical synapses, are potentiated in spared cortex. In the present work we also found ipsilateral activation of barrel cortex in response to stimulation of the spared input. This is consistent with the previous study showing ipsilateral BOLD-fMRI responses in the deprived forepaw S1 cortex (Pelled et al., 2009). A detailed analysis of the mechanisms for this ipsilateral response will be the subject of a future study.

Numerous reports provide evidence for modification of intracortical synapses for L4 barrel plasticity in adolescent and adult rodents with no contribution from plasticity at TC inputs in a variety of different manipulations (Armstrong-James et al., 1994; Diamond et al., 1993; Diamond et al., 1994; Fox, 1992; Fox et al., 2002; Rema et al., 2006; Wallace and Fox, 1999). This is consistent with the critical period for TC plasticity being restricted to the first postnatal week (Brecht, 2007; Diamond et al., 1994; Fox, 1992; Fox et al., 2002). This TC critical period corresponds to a time when silent synapses are present and long-term synaptic plasticity can be induced at TC inputs to L4 (Crair and Malenka, 1995; Daw et al., 2007b; Feldman et al., 1998; Isaac et al., 1997; Kidd and Isaac, 1999). Nevertheless, in contrast to the observations on the slice preparation studies, there is growing evidence to show the potential contribution of changes of TC inputs to adult brain plasticity detected in vivo (Cooke and Bear, 2010; Hogsden and Dringenberg, 2009; Lee and Ebner, 1992). In the present study the MEMRI and slice electrophysiology data demonstrate that changes in TC inputs to L4 make a major contribution to experience dependent plasticity in the mature brain past the end of the TC critical period. There is evidence from a recent study showing altered TC axonal innervation to L4 barrels of adolescent and adult rats following chronic whisker manipulations (Wimmer et al. 2010). Other studies show that the dendritic arborization pattern and the density of excitatory/inhibitory synapses in L4 barrels are sensitive to whisker experience in adult animals (Knott et al., 2002; Tailby et al., 2005). Such anatomical changes are consistent with our MEMRI tracing data. Indeed, the MEMRI signal may reflect a contribution from Mn2+ accumulated in dendritic arbors of L4 neurons because the trans-synaptic transport becomes more efficient due to synaptic strengthening.

Mechanisms of experience-dependent plasticity in adult barrel cortex

Our data show that strengthening of the TC input to L4 stellate cells in spared barrel cortex is a prominent mechanism for plasticity in the mature brain after peripheral nerve injury. TC inputs strongly engage feed forward inhibitory interneurons in L4 barrel cortex (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Cruikshank et al., 2007; Daw et al., 2007a; Gabernet et al., 2005; Porter et al., 2001; Sun et al., 2006), and notably the ratio of feedforward inhibition and excitation in L4 was unaffected in IO rats. This demonstrates that inhibition was similarly potentiated with the increased excitation in these animals. This parallel enhancement of feed forward inhibition could be due to an increase in TC input strength onto feed forward interneurons, and/or an increase in their excitability and/or an increase in their connectivity to stellate cells. In other studies, it has been shown that during development the excitability of feed forward interneurons, the strength of TC inputs onto feed forward interneurons and the strength of inhibitory synaptic transmission onto stellate cells in L4 barrel cortex can all be regulated by whisker-driven activity (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Jiao et al., 2006; Sun et al., 2009). Furthermore, the most prominent effect of whisker activity on synaptic anatomy is an increase in GABAergic synapses (Knott et al., 2002). Thus multiple mechanisms could contribute to the scaling of inhibition with excitation in L4 barrel cortex.

The spared TC input exhibits increased quantal amplitude and an increased number of functional synapses. This is suggestive of an LTP mechanism underlying the strengthening of the spared input. There is considerable evidence that long-term synaptic plasticity mechanisms underlie experience-dependent plasticity in primary sensory cortical areas (Feldman, 2009; Malenka and Bear, 2004). However, previous studies have demonstrated that both LTP and LTD at TC inputs in L4 barrel cortex declines during the first postnatal week and is absent by the second postnatal week (Crair and Malenka, 1995; Daw et al., 2007b; Feldman et al., 1998; Isaac et al., 1997). Thus, our results suggest that the two week loss of sensory input to the contralateral barrel cortex in 4-6 week old rats re-activates LTP-like plasticity at TC inputs in spared barrel cortex.

It is not clear whether the increased TC input underlies the full BOLD-fMRI increase detected in the cortex of IO rats. Although our findings on a lack of change in the IC fEPSP and in spontaneous EPSCs and IPSCs suggest no local change in intracortical synaptic strength in L4, it is probable that other mechanisms outside L4 could act in addition to TC input strengthening to contribute to the increased BOLD signal observed. In addition, IO nerve resection may modify subcortical and long range cortical connections to mediate an increase in excitability of the L4 network in response to stimulation of input to spared cortex. Such mechanisms would not be readily detectible in slice preparations, and would be a topic for future studies.

In conclusion, our data demonstrate that TC inputs to L4 can be a site of plasticity after the end of the critical period. Moreover, the use of the combined MRI and electrophysiology approach provides a powerful method for whole-brain mapping of plasticity mechanisms that would be readily applicable to a number of lesion, behavioral and pharmacological paradigms.

Experimental Procedures

Infraorbital denervation

All animal work was performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Care and Use Committee and the Animal Health and Care Resection of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD, USA). 4-week old Sprague-Dawley rats were anesthetized with isoflurane. The infraorbital denervation procedure was descriped previously (Dietrich et al., 1985). Briefly, the infraorbital branch of the trigeminal nerve was first exposed as it emerges from the infraorbital foramen in a broad band of fibers fanning out in all directions to the skin of the snout and to the vibrissal roots. The infraorbital fiber bundles were stretched from the infraorbital foramen and then tightly ligated just distal to the infraorbital foramen to prevent regeneration. Up to 2-3 mm distal to the ligature was cauterized towards the vibrissal roots. For those undergoing a sham procedure, incisions were made and the nerve exposed, but nerve bundle ligation and cauterization was not performed. Rats were allowed to recover for 14-18 days before MRI imaging and electrophysiological recordings. The proximal stump of the cauterized nerve was examined following MRI and no signs of regrowth towards the whisker pad and snout area from the infraorbital foramen were observed. There were a total 58 IO and 52 sham rats. Among all of these rats, 28 IO and 27 sham rats were used for MRI imaging, and 30 IO and 25 sham rats were used for electrophysiological recordings.

Animal preparation for functional MRI

MRI was performed as previously described (Yu et al., 2010). Rats were initially anesthetized with isoflurane. Each rat was orally intubated and placed on a mechanical ventilator. Plastic catheters were inserted into the right femoral artery and vein to allow monitoring of arterial blood gases and administration of drugs. After surgery, all rats were given i.v. bolus of α-chloralose (80mg/kg) and isoflurane was discontinued. Anesthesia was maintained with a constant infusion of α-chloralose (26.5mg/kg/h) in combination with pancuronium bromide (4 mg/kg/h) to reduce motion artifacts. A heated water pad maintained rectal temperature at ∼37.5°C. Each rat was secured in a head holder with a bite bar to prevent head motion. End-tidal CO2, rectal temperature, tidal pressure of ventilation, heart rate, and arterial blood pressure were continuously monitored during the experiment. Arterial blood gas levels were checked periodically and corrections were made by adjusting respiratory volume or administering sodium bicarbonate to maintain normal levels.

Electrical stimulation of the whisker pad and forepaw was described in our previous study (Yu et al., 2010). For the forepaw stimulation, two needle electrodes were inserted between digits 1, 2 and 3, 4. Electrical stimulation of the whisker pad was used (Berwick et al., 2004). For whisker pad stimulation, an electrode pad with five pins (one cathode in the center of a 5×5 mm square with four anodes at each corner) was designed. To reduce the cross-subject variation, the center pin was positioned at the third whisker of the caudal side of Row C for each rat. An isolated stimulator (WPI, FL) supplied 330 μs pulses repeated at 3Hz to the whisker pad and forepaw simultaneously upon demand at varying amount. The electrical current was set from 1.0 to 3.0mA with 0.5mA increments to the whisker pad. It is noteworthy that electrical stimulation at 2.5-3.0mA led to the subcortical BOLD-fMRI responses in the ipsilateral thalamic area and habenular nuclei, which could be related to pain processing at the high stimulation intensities (Hikosaka, 2010).

Mn-tracing preparation

A detailed procedure was described previously (Tucciarone et al., 2009). For thalamic injections, rats received 250nl of 50 mM MnCl2 solution (0.9% saline) into the left hemisphere (Bregma -3.0, lateral − 3.0, and ventral 5.7 mm), contralateral to the intact whisker pad of IO rats. The stereotactic coordinates were determined according to the Paxinos and Watson atlas (6th edition. Animals were anesthetized by isoflurane. A small bur hole was drilled after exposing the skull. A homemade glass injection needle was placed at the proper coordinates in the stereotactic frame. Injections were performed slowly over 5–6 min using a microinjector (Narishige, Tokyo) and the needle was slowly removed after being kept into the injection site for 10 min. MRI was performed right after stereotactic injections to make sure MnCl2 delivered to the proper site and at 4 to 6 h post injection to analyze Mn in the cortical lamina (Tucciarone et al., 2009). For MRI scans, rats were anaesthetized with 1–2% isoflurane using a nose cone and rectal temperature was maintained at 37 ± 1 °C by a heated water bath. After surgery and in between scans, the rats were allowed to recover and were free to roam within their cages. No abnormalities were observed after injection in all rats.

MRI image acquisition

All images were acquired with an 11.7 T/31 cm horizontal bore magnet (Magnex, Abingdon, UK), interfaced to an AVANCE III console (Bruker, Germany) and equipped with a 12 cm gradient set, capable of providing 100 G/cm with a rise time of 150μs (Resonance Research, MA). A custom-built 9 cm diameter quadrature transmitter coil was attached to the gradient. A 1 cm diameter surface receive coil with transmitting/receiving decoupling device were used during imaging acquisition. The fMRI imaging setup included shimming, adjustments to echo spacing and symmetry, and B0 compensation. A 3D gradient-echo, EPI sequence with a 64 × 64 ×32 matrix was run with the following parameters: effective echo time (TE) 16ms, repetition time (TR) 1.5s (effective TR 46.875ms), bandwidth 170kHz, flip angle 12°, FOV 1.92 × 1.92 × 0.96 cm. A two block design stimulation paradigm was applied in this study. For the simultaneous forepaw and whisker pad stimulation experiment, the paradigm consisted of 320 dummy scans to reach steady state; followed by 20 scans pre-stimulation, 20 scans during electrical stimulation, and 20 scans post-stimulation, which was repeated 3 times (140 scans were acquired overall). 6-8 multiple trials were acquired for each rat. For whisker-pad stimulation at different intensities (1.0-3.0mA), the paradigm consisted of 320 dummy scans to reach steady state, followed by 20 scans pre-stimulation, 10 scans during electrical stimulation, and 20 scans post-stimulation, which was repeated 3 times (110 scans were acquired overall). 3-5 multiple trials were repeated in a random order at different stimulation intensities with a total of 15-20 trials acquired for each rat. For the Mn-tracing study, a Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo (MP-RAGE) sequence (Mugler and Brookeman, 1990) was used. Sixteen coronal slices with FOV = 1.92 × 1.44 cm, matrix 192× 144, thickness = 0.5 mm (TR = 4000 ms, Echo TR/TE = 15/5 ms, TI = 1000 ms, number of segments = 4, Averages = 10) were used to cover the area of interest at 100 μm in-plane resolution with total imaging time 40 min. To measure intensity in the thalamus across animals, a T1-map was acquired using a Rapid Acquisition with Refocused Echoes (RARE) sequence with a similar image orientation to the MP-RAGE sequence (TE=9.6ms, Multi-TR=0.5s, 1s, 1.9s, 3.2s and 10s, Rare factor=2). For the purpose of cross-subject registration, T1-weigted anatomical images were also acquired in the same orientation as that of the 3D EPI and MPRAGE images with the following parameters: TR=500ms, TE=4ms, flip angle 45°, in-plane resolution 100 μm.

Electrophysiology

Thalamocortical (TC) slices (450 μM) were prepared from adult Sprague-Dawley Rats (6 -7 weeks) with some modifications of the method described previously (Agmon and Connors, 1991; Isaac et al., 1997) Briefly, after rats were anesthetized with isoflurane, the brain was rapidly cooled via transcardiac perfusion with ice-cold sucrose- artificial cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The brain was removed and placed in ice-cold sucrose-artificial CSF. Paracoronal slices were prepared at an angle of 50° relative to the midline on a ramp at an angle of 10°. Then, slices were incubated in artificial CSF at 35°C for 30 min to recover. Slices were then incubated in artificial CSF at room temperature (23°C -25°C) for 1-4 hours before being placed in the recording chamber for experiments. The standard artificial CSF contained (mM) 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.3 MgSO4, 1.0 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaH2CO3, 11 glucose, 1 Na pyruvate, 0.4 Na ascobate saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. Sucrose-artificial CSF contained (mM) 198 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 1 NaH2PO4, 26.2 NaHCO3, 11 glucose, 1 Na pyruvate, 0.4 Na ascorbate saturated with 95% O2/5% CO2. All experiments were conducted at 27°C – 29°C.

For electrophysiological experiments, electrodes with 3-6 MΩ pipette resistance were used and stimuli were applied to the VPM using a concentric bipolar electrode (FHC, Bowdoin, ME). The somatosensory cortex was identified by the presence of barrels under low power magnification and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics and by the ability to evoke short and constant latency fEPSPs by VPM stimulation (Agmon and Connors, 1991). Whole-cell voltage-clamp recordings were made from spiny stellate neurons in layer IV of the somatosensory cortex using infrared illumination and differential interference contrast (DIC) optics. The whole-cell recording solution was as follows (mM): 135 Cs methanesulfonate, 8 NaCl, 10 Hepes, 0.5 EGTA, 4 Mg-ATP, 0.3 Na-GTP and 5 QX-315 Cl (pH 7.25 with CsOH, 285 mOsm). Cells were held at -70 mV during recordings unless otherwise indicated. Recordings were made using a multiclamp 700B (Molecular devices, Sunnyvale, CA) digitized at 10 KHz and filtered at 2 KHz. Input resistance and series resistance were monitored continuously during recordings, as previously described (Isaac et al., 1995). EPSCs were accepted as monosynaptic if they exhibited a short and constant latency that did not change with increasing stimulus intensity. TC EPSC and EPSPs were evoked at a frequency of 0.1 Hz using a bipolar stimulating electrode placed in the VPM.

To examine disynaptic feedforward inhibition onto stellate cells, we measured IPSC:EPSC (‘GABA:AMPA’) ratio. The intensity of the stimulus (typically 10–40 V) was adjusted to produce an EPSC of 150 - 200 pA in amplitude in the stellate cell. The peak amplitude of the GABAA receptor–mediated IPSC was measured at 0 mV and the peak amplitude of the AMPA receptor–mediated EPSC was measured at −70 mV as previously reported (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Daw et al., 2007a). For experiments on short-term plasticity, the responses to a brief train stimulus (50 Hz) were obtained by averaging 10 trials. For estimation of peak amplitude of each EPSC during a train stimulus, postsynaptic summation was removed, as previously described (Kidd et al., 2002).

To measure evoked miniature EPSCs, stable whole-cell voltage clamp recordings were performed with artificial CSF in which 4 mM Sr2+ was substituted for 4 mM Ca2+. Quantal events were detected and collected within a 200 ms window beginning 100 ms after VPM stimulation using a sliding template algorithm. Miniature EPSCs/IPSCs were also measured (detail experimental procedure in Supplementary note-1). For the minimal-stimulation protocol, thalamic stimulation intensity was adjusted until the lowest intensity that elicited a mixture of responses and failures was detected. Failure rate was calculated as number of failures/total number of trials. Potency was calculated as the mean EPSC peak amplitude excluding failures (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Isaac et al., 1997; Stevens and Wang, 1995). The criteria for single-axon stimulation were (1) all or none synaptic events, (2) little or no change in the mean amplitude of the EPSC evoked by small increases in stimulus intensity, as previously reported (Chittajallu and Isaac, 2010; Gil et al., 1999). Data was collected for 20 trials at 0.1 Hz.

Imaging Processing and Statistical Analysis

MRI data analysis was performed using Analysis of Functional NeuroImages software (AFNI) (NIH, Bethesda) and C++. Similar to the previously reported imaging processing procedure (Yu et al., 2010), a detailed description is included in the supplementary note-2. The beta value of each voxel was derived from a linear regression analysis to estimate the amplitude of BOLD response(Cox, 1996), which is briefly described in the following equation:

(Yi are the measurements, Xi are the known regressors or predictor variables, βi are the unknown parameters to be estimated for each voxel, εi are random errors). The beta value (0-5) estimates the amplitude of the BOLD response in the beta maps as shown in the color bar (Figure 1, 2). To provide a brain-atlas-based region of interest in the cortex and thalamus of the rat brain, MRI images were registered to the brain atlas using C++ and Matlab programming (Supplementary note-3). A diagram of the image processing is shown in Supplementary Figure 1.

Statistics and graphical representation

All summary data were presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were carried out using two-tailed, unpaired T test or the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test as appropriate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NINDS. We thank Dr. Afonso Silva for his supports to provide the in vivo recording environment and the help from Mr. Colin Gerber and Ms. Marian Wahba. We thank Ms. Kathryn Sharer, Ms. Nadia Bouraoud, and Ms. Lisa Zhang for their technical supports.

References

- Agmon A, Connors BW. Thalamocortical responses of mouse somatosensory (barrel) cortex in vitro. Neuroscience. 1991;41:365–379. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(91)90333-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agmon A, Connors BW. Correlation between intrinsic firing patterns and thalamocortical synaptic responses of neurons in mouse barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 1992;12:319–329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-01-00319.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agmon A, O'Dowd DK. NMDA receptor-mediated currents are prominent in the thalamocortical synaptic response before maturation of inhibition. J Neurophysiol. 1992;68:345–349. doi: 10.1152/jn.1992.68.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong-James M, Diamond ME, Ebner FF. An innocuous bias in whisker use in adult rats modifies receptive fields of barrel cortex neurons. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6978–6991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06978.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister NJ, Benke TA, Mellor J, Scott H, Gurdal E, Crabtree JW, Isaac JT. Developmental changes in AMPA and kainate receptor-mediated quantal transmission at thalamocortical synapses in the barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5259–5271. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0827-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick J, Redgrave P, Jones M, Hewson-Stoate N, Martindale J, Johnston D, Mayhew JE. Integration of neural responses originating from different regions of the cortical somatosensory map. Brain Res. 2004;1030:284–293. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgen M, Peng W, Al-Hafez B, Dancause N, He YY, Cheney PD. Electrical stimulation of cortex improves corticospinal tract tracing in rat spinal cord using manganese-enhanced MRI. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;156:17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brecht M. Barrel cortex and whisker-mediated behaviors. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2007;17:408–416. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2007.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buonomano DV, Merzenich MM. Cortical plasticity: from synapses to maps. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1998;21:149–186. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.21.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals S, Beyerlein M, Keller AL, Murayama Y, Logothetis NK. Magnetic resonance imaging of cortical connectivity in vivo. Neuroimage. 2008;40:458–472. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Alamancos MA. Dynamics of sensory thalamocortical synaptic networks during information processing states. Prog Neurobiol. 2004;74:213–247. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittajallu R, Isaac JT. Emergence of cortical inhibition by coordinated sensory-driven plasticity at distinct synaptic loci. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1240–1248. doi: 10.1038/nn.2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke SF, Bear MF. Visual experience induces long-term potentiation in the primary visual cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:16304–16313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4333-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox RW. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 1996;29:162–173. doi: 10.1006/cbmr.1996.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crair MC, Malenka RC. A critical period for long-term potentiation at thalamocortical synapses. Nature. 1995;375:325–328. doi: 10.1038/375325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer SC, Sur M, Dobkin BH, O'Brien C, Sanger TD, Trojanowski JQ, Rumsey JM, Hicks R, Cameron J, Chen D, et al. Harnessing neuroplasticity for clinical applications. Brain. 2011;134:1591–1609. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruikshank SJ, Lewis TJ, Connors BW. Synaptic basis for intense thalamocortical activation of feedforward inhibitory cells in neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:462–468. doi: 10.1038/nn1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Ashby MC, Isaac JT. Coordinated developmental recruitment of latent fast spiking interneurons in layer IV barrel cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2007a;10:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nn1866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daw MI, Scott HL, Isaac JT. Developmental synaptic plasticity at the thalamocortical input to barrel cortex: mechanisms and roles. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007b;34:493–502. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond ME, Armstrong-James M, Ebner FF. Experience-dependent plasticity in adult rat barrel cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2082–2086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond ME, Huang W, Ebner FF. Laminar comparison of somatosensory cortical plasticity. Science. 1994;265:1885–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.8091215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietrich WD, Ginsberg MD, Busto R, Smith DW. Metabolic alterations in rat somatosensory cortex following unilateral vibrissal removal. J Neurosci. 1985;5:874–880. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-04-00874.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dijkhuizen RM, Ren JM, Mandeville JB, Wu ON, Ozdag FM, Moskowitz MA, Rosen BR, Finklestein SP. Functional magnetic resonance imaging of reorganization in rat brain after stroke. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:12766–12771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231235598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrunz LE, Stevens CF. Heterogeneity of release probability, facilitation, and depletion at central synapses. Neuron. 1997;18:995–1008. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80338-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE. Synaptic mechanisms for plasticity in neocortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:33–55. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE, Brecht M. Map plasticity in somatosensory cortex. Science. 2005;310:810–815. doi: 10.1126/science.1115807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman DE, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC, Isaac JT. Long-term depression at thalamocortical synapses in developing rat somatosensory cortex. Neuron. 1998;21:347–357. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80544-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. A critical period for experience-dependent synaptic plasticity in rat barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 1992;12:1826–1838. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-05-01826.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. Anatomical pathways and molecular mechanisms for plasticity in the barrel cortex. Neuroscience. 2002;111:799–814. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00027-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. Experience-dependent plasticity mechanisms for neural rehabilitation in somatosensory cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2009;364:369–381. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2008.0252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K, Wallace H, Glazewski S. Is there a thalamic component to experience-dependent cortical plasticity? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2002;357:1709–1715. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabernet L, Jadhav SP, Feldman DE, Carandini M, Scanziani M. Somatosensory integration controlled by dynamic thalamocortical feed-forward inhibition. Neuron. 2005;48:315–327. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Connors BW, Amitai Y. Efficacy of thalamocortical and intracortical synaptic connections: quanta, innervation, and reliability. Neuron. 1999;23:385–397. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80788-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goda Y, Stevens CF. Two components of transmitter release at a central synapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12942–12946. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goloshevsky AG, Silva AC, Dodd SJ, Koretsky AP. BOLD fMRI and somatosensory evoked potentials are well correlated over a broad range of frequency content of somatosensory stimulation of the rat forepaw. Brain Res. 2008;1195:67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heeger DJ, Huk AC, Geisler WS, Albrecht DG. Spikes versus BOLD: what does neuroimaging tell us about neuronal activity? Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:631–633. doi: 10.1038/76572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. Critical period regulation. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2004;27:549–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.27.070203.144327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hikosaka O. The habenula: from stress evasion to value-based decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:503–513. doi: 10.1038/nrn2866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogsden JL, Dringenberg HC. Decline of long-term potentiation (LTP) in the rat auditory cortex in vivo during postnatal life: involvement of NR2B subunits. Brain Res. 2009;1283:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooks BM, Chen C. Critical periods in the visual system: changing views for a model of experience-dependent plasticity. Neuron. 2007;56:312–326. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel FC, Cohen LG. Drivers of brain plasticity. Curr Opin Neurol. 2005;18:667–674. doi: 10.1097/01.wco.0000189876.37475.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyder F, Rothman DL, Shulman RG. Total neuroenergetics support localized brain activity: implications for the interpretation of fMRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10771–10776. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132272299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Crair MC, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Silent synapses during development of thalamocortical inputs. Neuron. 1997;18:269–280. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80267-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac JT, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Evidence for silent synapses: implications for the expression of LTP. Neuron. 1995;15:427–434. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao Y, Zhang C, Yanagawa Y, Sun QQ. Major effects of sensory experiences on the neocortical inhibitory circuits. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8691–8701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2478-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EG. Cortical and subcortical contributions to activity-dependent plasticity in primate somatosensory cortex. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2000;23:1–37. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.23.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH. Plasticity of sensory and motor maps in adult mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1991;14:137–167. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.14.030191.001033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Collins CE. Anatomic and functional reorganization of somatosensory cortex in mature primates after peripheral nerve and spinal cord injury. Adv Neurol. 2003;93:87–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaas JH, Qi HX, Burish MJ, Gharbawie OA, Onifer SM, Massey JM. Cortical and subcortical plasticity in the brains of humans, primates, and rats after damage to sensory afferents in the dorsal columns of the spinal cord. Exp Neurol. 2008;209:407–416. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmarkar UR, Dan Y. Experience-dependent plasticity in adult visual cortex. Neuron. 2006;52:577–585. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd FL, Coumis U, Collingridge GL, Crabtree JW, Isaac JT. A presynaptic kainate receptor is involved in regulating the dynamic properties of thalamocortical synapses during development. Neuron. 2002;34:635–646. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00699-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd FL, Isaac JT. Developmental and activity-dependent regulation of kainate receptors at thalamocortical synapses. Nature. 1999;400:569–573. doi: 10.1038/23040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knott GW, Quairiaux C, Genoud C, Welker E. Formation of dendritic spines with GABAergic synapses induced by whisker stimulation in adult mice. Neuron. 2002;34:265–273. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI. Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:1412–1425. doi: 10.1162/0898929042304796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SM, Ebner FF. Induction of high frequency activity in the somatosensory thalamus of rats in vivo results in long-term potentiation of responses in SI cortex. Exp Brain Res. 1992;90:253–261. doi: 10.1007/BF00227236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefort S, Tomm C, Floyd Sarria JC, Petersen CC. The excitatory neuronal network of the C2 barrel column in mouse primary somatosensory cortex. Neuron. 2009;61:301–316. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YJ, Koretsky AP. Manganese ion enhances T1-weighted MRI during brain activation: an approach to direct imaging of brain function. Magn Reson Med. 1997;38:378–388. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910380305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T, Oeltermann A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature. 2001;412:150–157. doi: 10.1038/35084005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HC, Gonzalez E, Crair MC. Barrel cortex critical period plasticity is independent of changes in NMDA receptor subunit composition. Neuron. 2001;32:619–634. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00501-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu HC, She WC, Plas DT, Neumann PE, Janz R, Crair MC. Adenylyl cyclase I regulates AMPA receptor trafficking during mouse cortical 'barrel' map development. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:939–947. doi: 10.1038/nn1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A, Wilke M, Aura C, Zhu C, Ye FQ, Leopold DA. Divergence of fMRI and neural signals in V1 during perceptual suppression in the awake monkey. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1193–1200. doi: 10.1038/nn.2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majewska AK, Sur M. Plasticity and specificity of cortical processing networks. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC, Bear MF. LTP and LTD: an embarrassment of riches. Neuron. 2004;44:5–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugler JP, 3rd, Brookeman JR. Three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient-echo imaging (3D MP RAGE) Magn Reson Med. 1990;15:152–157. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910150117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murayama Y, Weber B, Saleem KS, Augath M, Logothetis NK. Tracing neural circuits in vivo with Mn-enhanced MRI. Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;24:349–358. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2005.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Lee TM, Stepnoski R, Chen W, Zhu XH, Ugurbil K. An approach to probe some neural systems interaction by functional MRI at neural time scale down to milliseconds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:11026–11031. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.11026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pautler RG, Silva AC, Koretsky AP. In vivo neuronal tract tracing using manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1998;40:740–748. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelled G, Bergman H, Ben-Hur T, Goelman G. Manganese-enhanced MRI in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007a;26:863–870. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelled G, Bergstrom DA, Tierney PL, Conroy RS, Chuang KH, Yu D, Leopold DA, Walters JR, Koretsky AP. Ipsilateral cortical fMRI responses after peripheral nerve damage in rats reflect increased interneuron activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14114–14119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903153106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelled G, Chuang KH, Dodd SJ, Koretsky AP. Functional MRI detection of bilateral cortical reorganization in the rodent brain following peripheral nerve deafferentation. Neuroimage. 2007b;37:262–273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, Johnson CK, Agmon A. Diverse types of interneurons generate thalamus-evoked feedforward inhibition in the mouse barrel cortex. J Neurosci. 2001;21:2699–2710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-08-02699.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raastad M, Storm JF, Andersen P. Putative Single Quantum and Single Fibre Excitatory Postsynaptic Currents Show Similar Amplitude Range and Variability in Rat Hippocampal Slices. Eur J Neurosci. 1992;4:113–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1992.tb00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran VS. Plasticity and functional recovery in neurology. Clin Med. 2005;5:368–373. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.5-4-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees G, Friston K, Koch C. A direct quantitative relationship between the functional properties of human and macaque V5. Nature Neuroscience. 2000;3:716–723. doi: 10.1038/76673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rema V, Armstrong-James M, Jenkinson N, Ebner FF. Short exposure to an enriched environment accelerates plasticity in the barrel cortex of adult rats. Neuroscience. 2006;140:659–672. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sirotin YB, Das A. Anticipatory haemodynamic signals in sensory cortex not predicted by local neuronal activity. Nature. 2009;457:475–479. doi: 10.1038/nature07664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens CF, Wang Y. Facilitation and depression at single central synapses. Neuron. 1995;14:795–802. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90223-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QQ, Huguenard JR, Prince DA. Barrel cortex microcircuits: thalamocortical feedforward inhibition in spiny stellate cells is mediated by a small number of fast-spiking interneurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1219–1230. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4727-04.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun QQ, Zhang Z, Jiao Y, Zhang C, Szabo G, Erdelyi F. Differential metabotropic glutamate receptor expression and modulation in two neocortical inhibitory networks. J Neurophysiol. 2009;101:2679–2692. doi: 10.1152/jn.90566.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailby C, Wright LL, Metha AB, Calford MB. Activity-dependent maintenance and growth of dendrites in adult cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:4631–4636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402747102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucciarone J, Chuang KH, Dodd SJ, Silva A, Pelled G, Koretsky AP. Layer specific tracing of corticocortical and thalamocortical connectivity in the rodent using manganese enhanced MRI. Neuroimage. 2009;44:923–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugurbil K, Toth L, Kim DS. How accurate is magnetic resonance imaging of brain function? Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:108–114. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(02)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden A, Van Meir V, Boumans T, Poirier C, Balthazart J. MRI in small brains displaying extensive plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:257–266. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Linden A, Verhoye M, Van Meir V, Tindemans I, Eens M, Absil P, Balthazart J. In vivo manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging reveals connections and functional properties of the songbird vocal control system. Neuroscience. 2002;112:467–474. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Loos H, Woolsey TA. Somatosensory cortex: structural alterations following early injury to sense organs. Science. 1973;179:395–398. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4071.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Zijden JP, Bouts MJ, Wu O, Roeling TA, Bleys RL, van der Toorn A, Dijkhuizen RM. Manganese-enhanced MRI of brain plasticity in relation to functional recovery after experimental stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:832–840. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Meer MP, van der Marel K, Otte WM, Berkelbach van der Sprenkel JW, Dijkhuizen RM. Correspondence between altered functional and structural connectivity in the contralesional sensorimotor cortex after unilateral stroke in rats: a combined resting-state functional MRI and manganese-enhanced MRI study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010;30:1707–1711. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall JT, Xu J, Wang X. Human brain plasticity: an emerging view of the multiple substrates and mechanisms that cause cortical changes and related sensory dysfunctions after injuries of sensory inputs from the body. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2002;39:181–215. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00192-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace H, Fox K. The effect of vibrissa deprivation pattern on the form of plasticity induced in rat barrel cortex. Somatosens Mot Res. 1999;16:122–138. doi: 10.1080/08990229970564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolsey TA, Van der Loos H. The structural organization of layer IV in the somatosensory region (SI) of mouse cerebral cortex. The description of a cortical field composed of discrete cytoarchitectonic units. Brain Res. 1970;17:205–242. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(70)90079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Sanes DH, Aristizabal O, Wadghiri YZ, Turnbull DH. Large-scale reorganization of the tonotopic map in mouse auditory midbrain revealed by MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12193–12198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700960104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Wadghiri YZ, Sanes DH, Turnbull DH. In vivo auditory brain mapping in mice with Mn-enhanced MRI. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:961–968. doi: 10.1038/nn1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Wang S, Chen DY, Dodd S, Goloshevsky A, Koretsky AP. 3D mapping of somatotopic reorganization with small animal functional MRI. Neuroimage. 2010;49:1667–1676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Zou J, Babb JS, Johnson G, Sanes DH, Turnbull DH. Statistical mapping of sound-evoked activity in the mouse auditory midbrain using Mn-enhanced MRI. Neuroimage. 2008;39:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.