Abstract

Background

Over the last 10 years the number of medical students choosing family medicine as a career has steadily declined. Studies have demonstrated that career preference at the time that students begin medical school may be significantly associated with their ultimate career choice. We sought to identify the career preferences students have at entry to medical school and the factors related to family medicine as a first-choice career option.

Methods

A questionnaire was administered to students entering medical school programs at the time of entry at the University of Calgary (programs beginning in 2001 and 2002), University of British Columbia (2001 and 2002) and University of Alberta (2002). Students were asked to indicate their top 3 career choices and to rank the importance of 25 variables with respect to their career choice. Factor analysis was performed on the variables. Reliability of the factor scores was estimated using Cronbach's alpha coefficients; biserial correlations between the factors and career choice were also calculated. A logistic regression was performed using career choice (family v. other) as the criterion variable and the factors plus demographic characteristics as predictor variables.

Results

Of 583 students, 519 (89%) completed the questionnaire. Only 20% of the respondents identified family medicine as their first career option, and about half ranked family medicine in their top 3 choices. Factor analysis produced 5 factors (medical lifestyle, societal orientation, prestige, hospital orientation and varied scope of practice) that explained 52% of the variance in responses. The 5 factors demonstrated acceptable internal consistency and correlated in the expected direction with the choice of family medicine. Logistic regression revealed that students who identified family medicine as their first choice tended to be older, to be concerned about medical lifestyle and to have lived in smaller communities at the time of completing high school; they were also less likely to be hospital oriented. Moreover, students who chose family medicine were much more likely to demonstrate a societal orientation and to desire a varied scope of practice.

Interpretation

Several factors appear to drive students toward family medicine, most notably having a societal orientation and a desire for a varied scope of practice. If the factors that influence medical students to choose family medicine can be identified accurately, then it may be possible to use such a model to change medical school admission policies so that the number of students choosing to enter family medicine can be increased.

In Canada the number of medical students choosing family medicine as a career option is declining. The proportion of students selecting family medicine as a first choice for residency fell from a high of 44% in 1992 to 25% in 2003, the lowest percentage ever.1In 2004, there were 124 unmatched family medicine positions in the Canadian Resident Matching Service's (CaRMS) first iteration.2 After the second iteration, 29 positions remained unfilled.3 These results have left governments, medical workforce experts and all others interested in maintaining or increasing the number of family physicians expressing considerable concern.

The reasons why medical students choose their careers are complex. Factors shown to be associated with choosing family medicine include medical school characteristics,4,5,6,7,8,9 personal interactions,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17 and lifestyle preferences, personal fit and workforce factors, including expected income, prestige, job opportunities, longitudinal care and societal need.16,18,19,20,21,22,23

Others have demonstrated that career preference at the time of entering medical school may be a significant predictor of students' eventual career choice.4,24,25,26 Colwill, for example, suggests that students usually see themselves as either generalists or specialists at the start of medical school.27 Although there is movement during medical school between the desire to practise family medicine and the desire to practise specialty care, many students end up in careers that are closely related to their choice at the beginning of medical school.28 Consequently, defining the factors that influence career choice at the start of medical school is important.

The purpose of this study was twofold: to understand what career preferences medical students have at the beginning of medical school and to determine what factors influence choosing family medicine as a career.

Methods

Students in 5 medical school classes beginning their medical studies participated in the study: University of Calgary classes beginning 2001 and 2002, University of British Columbia classes beginning 2001 and 2002 and the University of Alberta class beginning 2002. International students were excluded from the study.

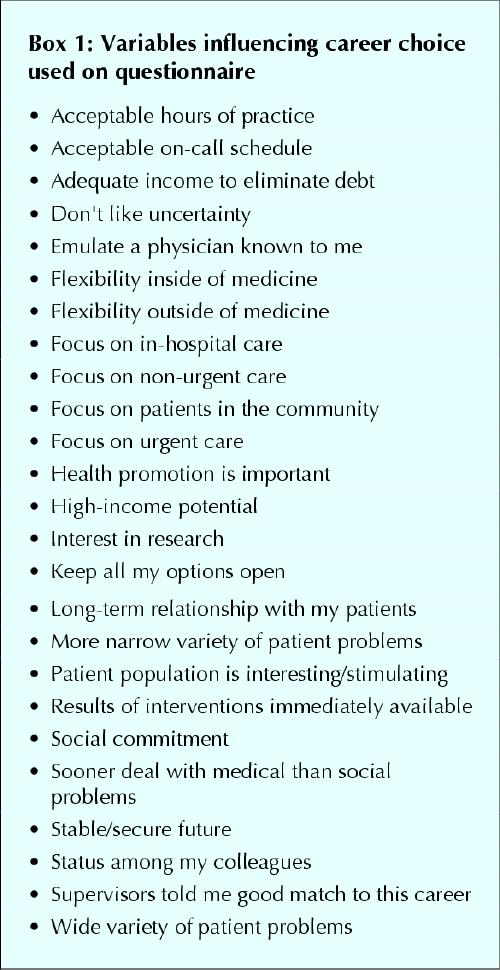

A 6-page questionnaire was administered within the first 2 weeks of the start of medical school. Using a yes or no response, students were first asked to consider 8 career options, including emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, surgery and other. They were then asked to rank their first 3 career choices as of that day. They then indicated the degree to which 25 variables (Box 1) influenced their first-ranked choice. Responses to the influences were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (no influence) to 5 (major influence). The variables presented were chosen based on a literature review and discussions with medical students, residents and educational leaders, and then subjected to a validation process, which included giving the questionnaire to medical students, residents, physicians and experts to check for item appropriateness and comprehensiveness (face and content validity). Variables listed in the questionnaire were modified based on this review. An initial version of the questionnaire was tested with the medical school class beginning at the University of Calgary in 2000.

Box 1.

Factor analysis was used to determine whether the 25 variables could be grouped together to create a smaller number of underlying factors. The research team predetermined that variables should correlate with a factor at 0.6 or higher to provide evidence of a strong relationship between the variables and each new factor. Variables that clustered into factors that explained more variance (eigenvalue > 1) than that of a single variable were retained. Cronbach's alpha coefficients were calculated to estimate the internal consistency of each factor, and biserial correlations were calculated between career choice (family medicine v. specialty medicine) and the factors. The difference in mean age between students choosing family medicine and those choosing a specialty was examined using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the relation between male and female students and career choice was analyzed using χ2. Finally, a stepwise logistic regression was performed using career choice (family medicine v. specialty medicine) as the criterion variable and the factors plus demographic characteristics (age, sex, population of community where the student completed high school) as predictor variables. All variables were treated as continuous data with the exception of sex and population of community where high school was completed, which were considered categorical. Variables were entered into the model if the associated significance was p < 0.05 and removed if the associated significance was p > 0.1.

Results

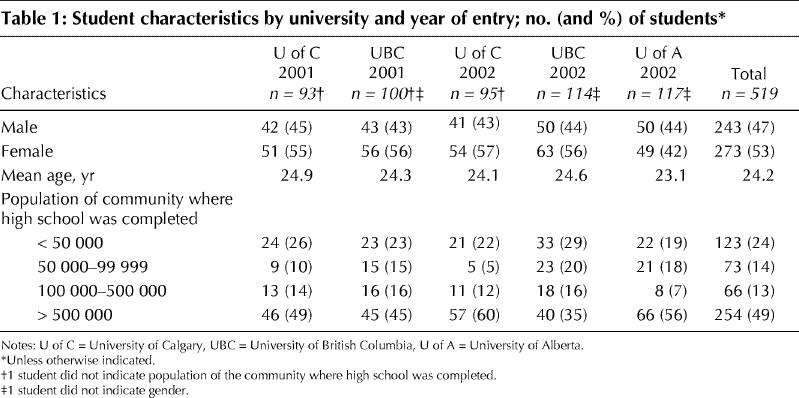

Of 583 questionnaires, 519 were completed, producing a response rate of 89%. Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of each class. Slightly more than half (273, 53%) of the respondents were female. The average age of the respondents was 24.2 years (standard deviation [SD] 3.5). In all, 254 respondents stated that the population of the community in which they completed high school was greater than 500 000 (49%, n = 516 as 3 did not respond to this question), 66 (13%) were from communities with populations between 100 000 and 500 000, 73 (14%) were from communities with populations between 50 000 and 99 999 and 123 (24%) were from communities with populations of less than 50 000. In the subsequent analysis, population of the community where high school was completed was coded 1–4, where 1 indicated populations greater than 500 000 and 4 indicated populations less than 50 000.

Table 1

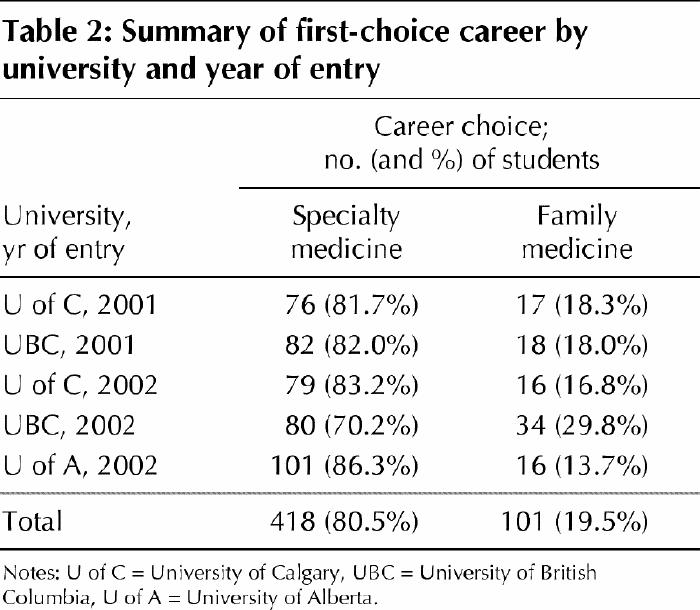

Table 2 displays first-choice career responses (family medicine v. specialty medicine) by university and year of entry. Overall, 19.5% reported family medicine as their first choice. The class entering the University of British Columbia in 2002 had the highest percentage (30%) and the class entering University of Alberta in 2002 had the lowest (13.7%). The average age of those who chose family medicine was significantly greater than the average age of those who chose specialty medicine (26.0 years [SD 5.1] v. 23.7 years [SD 2.9]; p < 0.05). Career choice broken down by sex illustrates that women chose family medicine first more often than men (23% v. 16%, p < 0.05).

Table 2

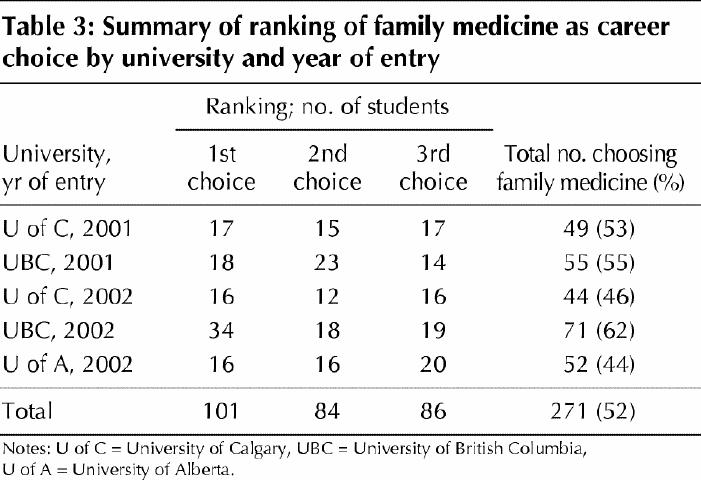

Table 3 displays the numbers of students, according to university and year of entry, who chose family medicine as a first, second or third career option. The percentage of students who ranked family medicine in 1 of the top 3 positions ranged from 44%, in the University of Alberta class entering in 2002, to 62% in the University of British Columbia class entering in 2002. Of all respondents, 53% ranked family medicine in 1 of the top 3 positions.

Table 3

The factor analysis on first-choice career responses produced 5 factors that used 17 of the 25 variables; 8 variables failed to correlate with any of the factors. Each factor was named by the authors according to how the variables grouped together. The 5 factors were labelled as Factor 1: medical lifestyle (acceptable on-call schedule, acceptable hours of practice, medical flexibility, nonmedical flexibility and keeping options open); Factor 2: societal orientation (focus on patients in the community, long-term relationship with patients, social commitment and promoting health); Factor 3: prestige (adequate income to eliminate debt, high-income potential and status among colleagues); Factor 4: hospital orientation (focus on in-hospital care, focus on urgent care and immediately available results of interventions); and Factor 5: varied scope of practice (wide variety of patient problems and more narrow variety of patients' problems; this last item was ranked in reverse). These 5 factors collectively explained 52% of the variance in the responses.

Correlations between family medicine as first career choice and the 5 factors were calculated as r = 0.16 for medical lifestyle, r = 0.43 for societal orientation, r = –0.13 for prestige, r = –0.31 for hospital orientation and r = 0.43 for varied scope of practice. A correlation near 0.5 (values from 1 to –1) indicates a moderate positive relation and a correlation of –0.5 indicates a moderate inverse relation.

Cronbach's alpha coefficients, estimating internal consistency of each factor, were calculated as α = 0.82 for medical lifestyle, α = 0.73 for societal orientation, α = 0.77 for prestige and α = 0.68 for hospital orientation. An alpha coefficient of 0.8 (out of 1) is considered the “gold standard” and indicative of high reliability. These coefficients are in the range that suggest moderate to high reliability. Because only 2 variables loaded on Factor 5 (varied scope of practice), a Pearson correlation (r = 0.54) was calculated and revealed a moderately strong relationship. For Factor 5, the item “more narrow variety of patient problems” was scored in reverse for the factor analysis, thereby producing a factor that reflected a varied scope of practice.

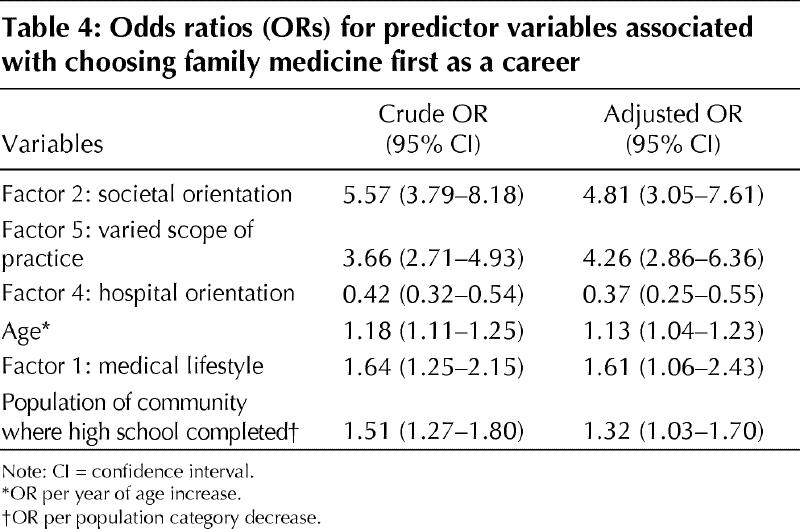

Stepwise logistic regression revealed that, in the following order, societal orientation (Factor 2), varied scope of practice (Factor 5), hospital orientation (Factor 4), age, medical lifestyle (Factor 1) and population of community where the student completed high school were predictive of career choice. Results of the logistic regression revealed that Factor 3 and sex were not included in the model and consequently not related to ranking family medicine as a first choice. Table 4 illustrates the odds ratios for each of the predictor variables. A significant association with the choice of family medicine for each variable in the model was observed. However, Factors 2 and 5 clearly had the strongest association with family medicine as first choice.

Table 4

Interpretation

Only 20% of new medical students participating in the study considered family medicine as their first career choice. There already exists a serious disconnect between the number of available training positions in family medicine and the number of students willing to pursue such a career. This study suggests that this problem is persisting. Factor analysis produced 5 factors that demonstrated acceptable internal consistency and described the important influences in shaping career preferences. The correlations between the 5 factors and family medicine as first career choice were in the expected directions and provide evidence for construct validity of the questionnaire. Sex differences also ran in the expected direction. The logistic regression analysis examined the association between several predictor variables and family medicine as a first-choice career. Students who identified family medicine as their first choice were more likely to be older, to be concerned about medical lifestyle and to have completed high school in smaller communities, and they were less likely to be hospital oriented. Most importantly, however, students who chose family medicine first were much more likely to demonstrate a societal orientation and to desire a varied scope of practice. In total, 101 students ranked family medicine first. However, an additional 170 (33%) ranked family medicine as either second or third choice — that is, at least half of the students in this study were considering family medicine as a possibility, although a majority of this group, at the time of entry, viewed family medicine as a back-up career. Alternatively, close to 50% of the students did not have family medicine among their first 3 choices.

Such low interest in family medicine is noteworthy because others have reported that a student's initial career preference is an important predictor of whether the student ultimately chooses a career in family medicine and that students tend not to switch into family medicine if it was not being considered at the outset of medical school.27,28 Should the percentage of students interested in family medicine as a first career option prove to reflect family medicine career preferences at graduation and across Canada, serious implications exist for the sustainability of our present health care model, which is based on access to a primary care physician. One solution to altering the decrease in the number of students choosing family medicine might be to change the admission policies of medical schools — that is, medical students might have to be selected, in part, because they want to be family physicians. The implications of such a large shift in policy would be significant. We also found evidence that at least half of the students at entry to medical school had family medicine on their “radar screens.” If the percentages of students who subsequently enter family medicine remain unchanged from the time of entry, the reasons why family medicine was discarded as a career possibility should be determined. Compared with a recent study that attempted to devise a similar model,29 the variance explained by the factors identified in this study is superior (52% v. 43%).

There are limitations to this study. Although the number of students who selected family medicine as their first choice mirrors recent CaRMs results, we do not know the ultimate career choices of this cohort. Dramatic shifts in career preferences could occur during medical school that would diminish the importance of assessing students at the beginning of school. Only 3 medical schools participated in this study and the results, therefore, might not describe what is occurring across Canada. Although our questionnaire went through a detailed development process, there may be other important influences that were not included on the form. Furthermore, there may be factors predictive of family medicine as a career choice (e.g., community involvement and volunteer work) that were not considered in this study. The high percentage of University of British Columbia students entering medical school in 2002 who chose family medicine first — 30% — is perplexing. There were no changes to the admission criteria between 2001 and 2002, and no demographic features help to explain why this class was so different from the other 4 groups (analysis not shown).

Following the classes through to graduation as an extension of this study is necessary. If, over time, it can be demonstrated that this model predicts ultimate career choices with reasonable accuracy, then the model may be used to help shape medical school admission policies to better match the needs of society to the aspirations of students who are to become physicians.

Conclusion

The proportion of new medical students showing a preference for family medicine is low. This study provided groundwork in identifying 4 factors and 2 demographic characteristics that predict family medicine as the career choice of some incoming medical students. Evidence of model reliability and validity was observed. Although this model shows promise in identifying factors that influence career choice, following the cohort to determine their actual career choice is necessary. Nevertheless, this initial work may prove to have an impact in eventually shaping the admission policies of Canadian medical schools.

β See related article page 1915

Acknowledgments

The research was supported by internal grants from the Department of Family Medicine at both the University of Calgary and the University of British Columbia. We acknowledge and wish to thank Dr. Peter Norton and Dr. Bob Woodard. We are indebted to Dr. Neil Drummond, who critically reviewed the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript and reviewed and approved the final revision. Dr. Wright was the principal author. Dr. Wright and Dr. Scott developed the questionnarie and study design, and both collected data. Dr. Brenneis critically reviewed the questionnaire, contributed to design and collected data. Dr. Woloschuk coordinated analysis of the data and contributed to study design.

Competing interests: None declared.

Correspondence to: Dr. Bruce Wright, c/o Admission Office, Faculty of Medicine, 3330 Hospital Drive, Calgary AB T2N 4N1; fax 403 210-8148; wrightb@ucalgary.ca

References

- 1.Banner S. Canadian Residency Matching Service (CaRMS): PGY-1 2003 Match Report. Available: www.carms.ca/stats/pgy-1_2003/page10_table9.htm (accessed 2004 May 19).

- 2.Banner S. Canadian Residency Matching Service (CaRMS): www.carms.ca/stats/stats2004.htm#results (accessed 2004 May 19).

- 3.Banner S. Canadian Residency Matching Service (CaRMS): www.carms.ca/stats/stats2004.htm#vacant2 (accessed 2004 May 19).

- 4.Senf JH, Campos-Outcalt D, Watkins AJ, Bastacky S, Killian C. A systematic analysis of how medical school characteristics relate to graduates' choices of primary care specialties. Acad Med 1997;72:524-33. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Whitcomb ME, Cullen TJ, Hart LG, Lishner DM, Rosenblatt RA. Comparing the characteristics of schools that produce high percentages and low percentages of primary care physicians. Acad Med 1992;67:587-91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Allen SS, Sherman MB, Bland CJ, Fiola JA. Effect of early exposure to family medicine on students' attitudes toward the specialty. J Med Educ 1987;62:911-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Campos-Outcalt D, Senf JH. Characteristics of medical schools related to the choice of family medicine as a specialty. Acad Med 1989;64:610-5. [PubMed]

- 8.Duerson MC, Crandall LA, Dwyer JW. Impact of a required family medicine clerkship on medical students' attitudes about primary care. Acad Med 1989; 64:546-8. [PubMed]

- 9.Meurer LN. Influence of medical school curriculum on primary care specialty choice: analysis and synthesis of the literature. Acad Med 1995;70:388-97. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Basco WT, Buchbinder SB, Duggan AK, Wilson MH. Associations between primary care-oriented practices in medical school admission and the practice intentions of matriculants. Acad Med 1998;73:1207-10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Katz LA, Sarnacki RE, Schimpfhauser F. The role of negative factors in changes in career selection by medical students. J Med Educ 1984;59:285-90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Paiva RE, Vu NV, Verhulst SJ. The effect of clinical experiences in medical school on specialty choice decisions. J Med Educ 1982;57:666-74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Steiner E, Stoken JM. Overcoming barriers to generalism in medicine: the residents' perspective. Acad Med 1995;70[Suppl]:94. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, Clark-Chiarelli N, Zotov N, Martin N, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18(3):159-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Geertsma RH, Romano J. Relationship between expected indebtedness and career choice of medical students. J Med Educ 1986;61:555-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Mutha S, Takayama JI, O'Neil EH. Insights into medical students' career choices based on third- and fourth-year students' focus-group discussions. Acad Med 1997;72:635-40. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Tardiff K, Cella D, Seiferth C, Perry S. Selection and change of specialties by medical school graduates. J Med Educ 1986;61:790-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Bland CJ, Meurer LN, Maldonado G. Determinants of primary care specialty choice: a non-statistical meta-analysis of the literature. Acad Med 1995;70:620-41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Ellsbury KE, Burack JH, Irby DM, Stritter FT, Ambrozy D, Carline JD, et al. The shift to primary care: emerging influences on specialty choice. Acad Med 1996;71[Suppl]:8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Fincher RM, Lewis LA, Rogers LQ. Classification model that predicts medical students' choices of primary care or non-primary care specialties. Acad Med 1992;67:324-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Kassebaum DG, Szenas PL, Schuchert MK. Determinants of the generalist career intentions of 1995 graduating medical students. Acad Med 1996;71:198-209. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Kassler WJ, Wartman SA, Silliman RA. Why medical students choose primary care careers. Acad Med 1991;66:41-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Rosenthal MP, Diamond JJ, Rabinowitz HK, Bauer LC, Jones RL, Kearl GW, et al. Influence of income, hours worked, and loan repayment on medical students' decision to pursue a primary care career. JAMA 1994;271:914-7. [PubMed]

- 24.Carline JD, Greer T. Comparing physicians' specialty interests upon entering medical school with their eventual practice specialties. Acad Med 1991;66:44-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Zeldow PB, Preston RC, Daugherty SR. The decision to enter a medical specialty: timing and stability. Med Educ 1992;26:327-32. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Pathman DE. Medical education and physicians' career choices: are we taking credit beyond our due? Acad Med 1996;71:963-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Colwill JM. Where have all the primary care applicants gone? N Engl J Med 1992; 326:387-93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Rabinowitz HK. The role of the medical school admission process in the production of generalist physicians. Acad Med 1999;74[Suppl]:44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Murdoch MM, Kressin N, Fortier L, Giuffre PA, Oswald L. Evaluating the psychometric properties of a scale to measure medical students' career-related values. Acad Med 2001;76:157-65. [DOI] [PubMed]