Abstract

Pediatric gliosarcoma (GS) is a rare variant of glioblastoma multiforme. The authors describe the case of an unusual pontine location of GS in a 9-year-old boy who was initially diagnosed with low-grade astrocytoma (LGA) that was successfully controlled for 4 years. Subsequently, his brain tumor transformed into a GS. Prior treatment of his LGA included subtotal tumor resection 3 times, standard radiation therapy, and Gamma Knife procedure twice. His LGA was also treated with a standard chemotherapy regimen of carboplatin and vincristine, and his GS with subtotal resection, high-dose cyclophosphamide, and thiotepa with stem cell rescue and temozolomide. Unfortunately, he developed disseminated disease with multiple lesions and leptomeningeal involvement including a tumor occupying 80% of the pons. Upon presentation at our clinic, he had rapidly progressing disease. He received treatment with antineoplastons (ANP) A10 and AS2-1 for 6 years and 10 months under special exception to our phase II protocol BT-22. During his treatment with ANP his tumor stabilized, then decreased, and, ultimately, did not show any metabolic activity. The patient’s response was evaluated by magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography scans. His pathology diagnosis was confirmed by external neuropathologists, and his response to the treatment was determined by central radiology review. He experienced the following treatment-related, reversible toxicities with ANP: fatigue, xerostomia and urinary frequency (grade 1), diarrhea, incontinence and urine color change (grade 2), and grade 4 hypernatremia. His condition continued to improve after treatment with ANP and, currently, he complains only of residual neurological deficit from his previous surgery. He achieved a complete response, and his overall and progression-free survival is in excess of 13 years. This report indicates that it is possible to obtain long-term survival of a child with a highly aggressive recurrent GS with diffuse pontine involvement with a currently available investigational treatment.

Key Words: antineoplastons A10, AS2-1, gliosarcoma, phase 2 trial, diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma, brainstem glioma

Gliosarcoma (GS) is classified as a variant of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), which consists of both glial and mesenchymal components.1 Up to 40% of both tumor types demonstrate TP53 mutations and CDKN2A and PTEN deletions, but in a GS, contrary to GBM, the abnormalities of EGFR are not frequent. In this respect GS resembles a mesenchymal variety of GBM.1,2 It is estimated that the incidence of GS among pediatric GBM is ∼2%.3 It is a very rare tumor, and, to the best of our knowledge, only 24 cases have been described in English-language professional journals, and none with pontine location.3–5 The literature describes the treatment of newly diagnosed cases of GS, which has resulted in a very poor median overall survival (OS) of <9 months.3 Despite an extensive search in literature, we could not find any case report on pediatric GS that recurred after surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy. Here, we discussed a case of GS with long-term OS and progression-free survival (PFS) after treatment with antineoplastons (ANP), which are synthetic analogs of naturally occurring amino acid derivatives that have an inhibitory effect on neoplastic growth.6,7 ANP A10 injection is a formulation comprising a 4:1 ratio of phenylacetylglutaminate sodium (PG) and phenylacetylisoglutaminate sodium (isoPG). ANP AS2-1 injection is a formulation of 4:1 ratio of phenylacetate sodium (PN) and PG. ANP A10 capsules contain 500 mg of 3-phenylacetylamino-2,6-piperidinedione, which is metabolized in the body to 4:1 ratio of PG, and isoPG and AS2-1 capsules contain 500 mg of 4:1 ratio of PN and PG.6

CASE REPORT

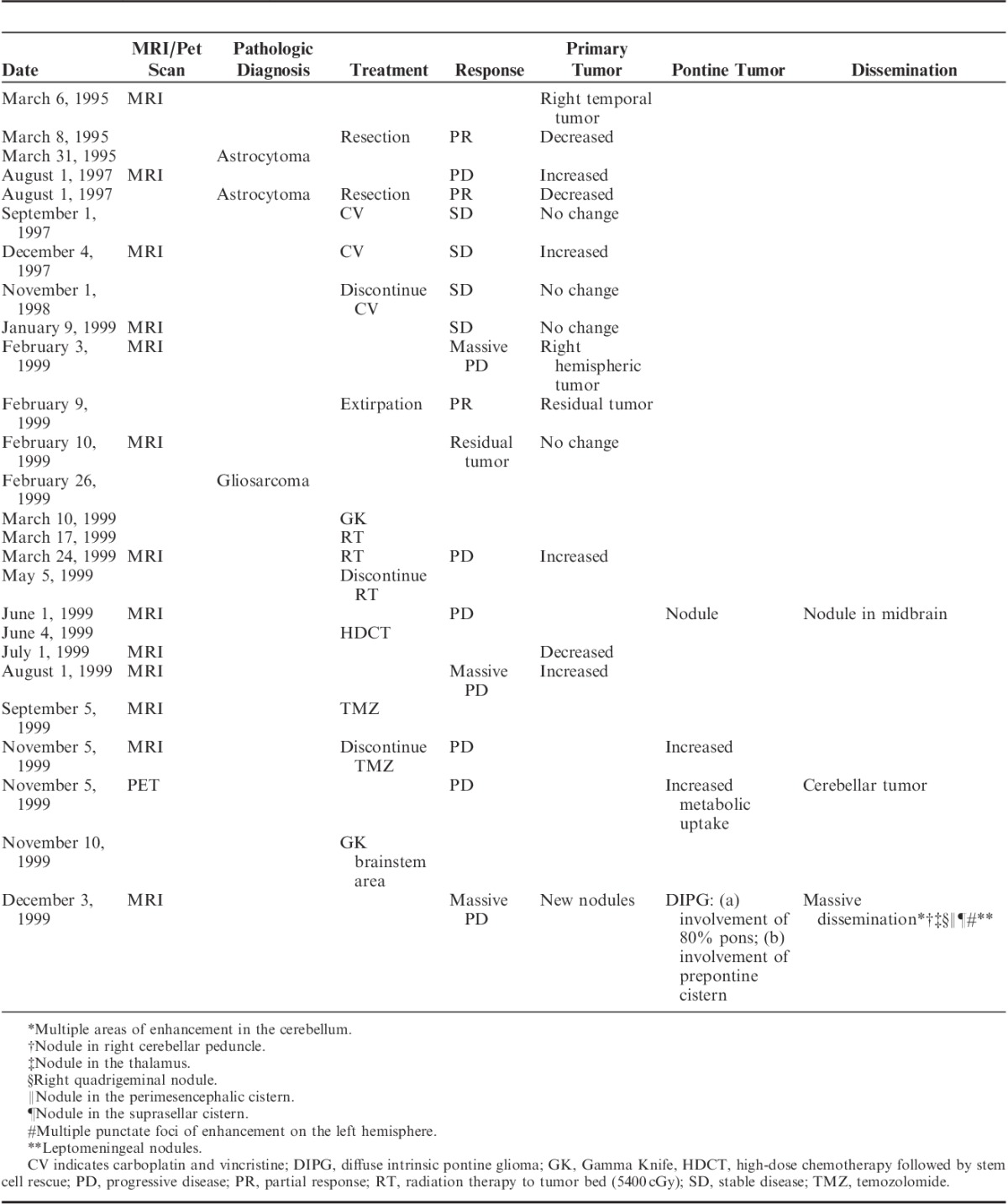

A 9-year-old white boy presented to our clinic in December 1999 with a 5-year history of brain tumor. He was in good health until the end of 1994 when he experienced repeated episodes of vomiting, which required multiple admissions to the local hospital. In March 1995 he suffered a series of grand mal seizures and was subsequently found to have a large right temporal brain tumor. He underwent craniotomy with 80% tumor resection; tumor biopsy resulted in a diagnosis of low-grade astrocytoma (LGA). He did well until 2½ years later when his symptoms and tumor recurred. He underwent a second craniotomy with the same pathologic diagnosis. From September 1997 he was treated for 14 months with a combination chemotherapy regimen of carboplatin and vincristine, which resulted in disease stabilization for 3 months. In February 1999 he developed massive progression, and his tumor tripled in size. He underwent a third craniotomy with 70% resection of the right hemispheric tumor, and partial temporal lobectomy. On this occasion, the initial pathologic diagnosis was high-grade glioma. The tissue was subsequently submitted to a consulting neuropathologist. The final diagnosis was GS. A month later, he underwent the Gamma Knife (GK) procedure, and on March 17, 1999 started radiation therapy (RT) of 5500 cGy to the tumor bed, which was completed on May 5, 1999. In early June 1999 his disease progressed, and 2 new lesions developed in the pons and midbrain for which he received treatment with high-dose cyclophosphamide and thiotepa, followed by stem cell rescue. He achieved reduction of the recurrent tumor, but unfortunately, a month later magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) indicated significant progression. On September 5, 1999, he was started on temozolomide (TMZ), but his disease progressed and he developed disseminated disease including diffuse intrinsic pontine tumor. On November 10, 1999, he underwent a second GK procedure to the brainstem area, which was not successful because of widespread metastatic disease with 8 major areas of involvement. A summary of treatment before admission to the Burzynski Clinic (BC) is provided in Table 1. The patient suffered typical adverse effects from his prior chemotherapy and RT. He developed severe neutropenia and thrombocytopenia and anemia. He had occasional temperature spikes, which may have been indicative of possible septicemia. He was frequently treated with antibiotics and was on pentamidine prophylaxis against Pneumocystis pneumonia. He was very tired, somnolent, and complained of generalized weakness. The child was evaluated at our clinic on December 2, 1999, his pathology diagnosis of initial LGA and GS having been established by external pathologists. At presentation he had a 2-month history of cranial nerve deficits including decreased vision, loss of left peripheral vision, drooling from the left side of the mouth and difficulty swallowing, ataxia, slurred speech, aphasia, left-sided weakness, tiredness, somnolence, fatigue, headaches, easy bruising, nocturnal urinary incontinence, mood swings, and difficulty with coordination. In the 2 weeks before presentation he had developed nausea without vomiting and experienced occasional epileptic seizures.

TABLE 1.

Summary of Prior Treatment

His physical examination confirmed his recent clinical history and was significant for visual deficit in the left eye with the left pupil smaller than the right, both with minimal reaction to light and accommodation. Extraocular movements were grossly intact. There was horizontal nystagmus with lateral gaze. The patient had facial nerve paresis with drooping of the left side of the face together with significant weakness and diminished sensory of the left side of the body. He also had significant adiadochokinesis and difficulty with finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin test on the right side, and was unable to perform those tests on the left. Babinski was upgoing, bilaterally. The Oppenheim sign was negative. The patient had significant ataxia. Deep tendon reflexes were normal on the left side, but diminished on the right. His Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) was 40.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

On December 3, 1999, the patient was admitted for treatment with A10 and AS2-1 intravenous infusions, on the basis of the FDA’s special exception to protocol BT-22. The exception was required as the patient had a KPS of <60 and brainstem involvement. Treatment with TMZ had been discontinued >4 weeks before the first administration of ANP with the most recent GK procedure carried out 3 weeks prior, and limited to the brainstem area. Protocol BT-22 was designed for children with primary malignant brain tumors who developed progressive disease within 8 weeks or less after completion of RT (including GK).

The study is listed by the National Cancer Institute and reviewed by the independent institutional review board, and all of the study subjects read, understood, and signed a written informed consent before enrollment. This study was conducted in accordance with the US code of federal regulations, Title 21, Parts 11, 50, 56, and 312; the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) including all amendments and revisions; the Good Clinical Practices: Consolidated Guideline (E6): International Conference on Harmonization; and the FDA’s Guidance for the Industry. The study was sponsored by the Burzynski Research Institute and conducted by the BC in Houston, TX. The patient did not pay for the investigational agents.

Histopathologic Examination

The initial pathologic examination was performed in the Department of Pathology at leading children’s hospitals in the United States. The first pathologic diagnosis was established on March 9, 1995, and was consistent with astrocytoma; but meningioma and schwannoma were also considered. The tissue was sent to a consulting pathologist, who, on March 31, 1995, confirmed that the histologic features were consistent with astrocytoma. The immunohistochemical staining analyses, performed at an outside laboratory, revealed negative glial fibrillary acidic protein and S-100, but were positive for vimentin in some cells, probably reflecting neoplastic astrocytes.

A second consultation was obtained from a chief pathologist at a leading medical university in the United States, who, on August 10, 1995, determined diagnosis of pilocytic astrocytoma on the basis of the slides from the first hospital, which did not include immunohistochemical stains.

The histopathologic evaluation of the tumor tissue, obtained on February 10, 1999, revealed features of high-grade glioma. The tissue was sent for evaluation by a neuropathologist at a different medical university, who determined, on February 26, 1999, the final diagnosis of GS, on the basis of identification of mesenchymal and glial components. The tumor had the typical features of frequent mitoses and a high proliferative index. It was highly positive for vimentin and glial fibrillary acidic protein. Reticulin stain was positive, which supported the diagnosis of GS.5 At the request of the parents, the slides were evaluated by a third consulting pathologist who did not perform immunostaining, and was not aware of prior immunohistochemical studies, and established the diagnosis of anaplastic astrocytoma. The neurooncologist in charge of the treatment of this patient, at a major children’s hospital in the United States, accepted the diagnosis of GS. The summary of prior pathologic diagnoses is provided in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Prior Pathologic Diagnoses

Treatment

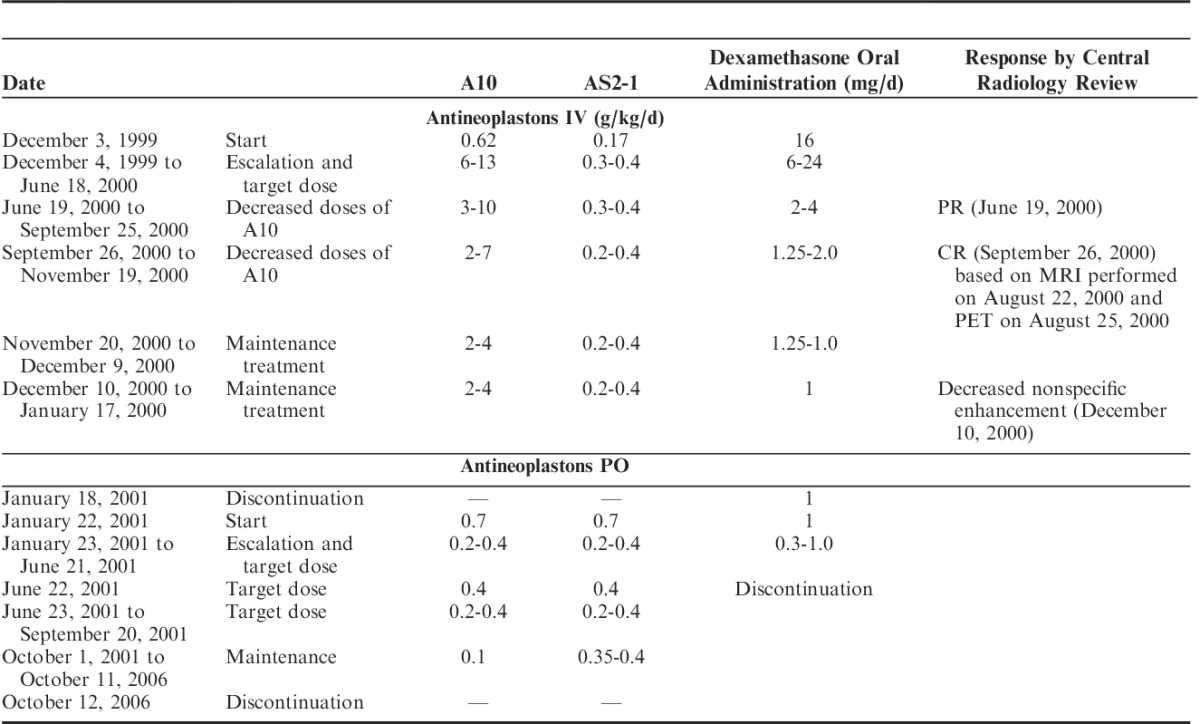

ANP A10 and AS2-1 were delivered by a dual-channel infusion pump and a single-lumen subclavian indwelling catheter (Broviac or Groshung) every 4 hours. On the first day of administration of ANP the starting dosages were A10 0.62 g/kg/d and AS2-1 0.17 g/kg/d. The initial flow rate of the pump was 50 mL/h. Beginning on the second day, the dosages were escalated and maintained at A10 10 to 13 g/kg/d and AS2-1 0.3 to 0.4 g/kg/d. The flow rate of the pump was increased to 75 mL/h on the second day, and to 150 mL/h on the third day, and subsequently maintained at this rate.

From June 19, 2000, the dosages of A10 were decreased to between 3 and 8 g/kg/d and AS2-1 to between 0.3 and 0.4 g/kg/d. From November 20, 2000, there was further decrease in the dosages of A10 to 2 to 4 g/kg/d and AS2-1 to 0.2 to 0.4 g/kg/d. The treatment with intravenous infusions was discontinued on January 18, 2001. On January 22, 2001, the patient began treatment with ANP A10 and AS2-1 0.5 g capsules. His initial dosage was 0.07 g/kg/d for both formulations and was gradually increased to 0.2 to 0.4 g/kg/d. On October 1, 2001, the dosage of A10 was decreased to 0.1 g/kg/d and AS2-1 to 0.35 to 0.4 g/kg/d. The treatment was discontinued on October 12, 2006 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Treatment and Response Data

The rationale for using 2 formulations of ANP was based on prior clinical trials.6 The escalation of the dosage of ANP was required on the basis of the results of prior studies to determine whether the patient was able to tolerate large-volume infusions of intravenous fluids associated with higher dosage of ANP.6 As a safety precaution, it was recommended that the escalation of the dosages continue to the phase II and phase III trial programs. The initial 3 weeks of therapy were administered by the BC staff on an outpatient basis in Houston, TX. The treatment did not require hospitalization. The patient and his parents were trained by the clinic staff to self administer ANP during this time. Starting on week 4, ANP was administered at home, with 24-hour support available by means of phone and e-mail. Treatment and monitoring of the patient’s conditions, through self-administration therapy, continued under the supervision of the patient’s local physician.

Before the start of treatment, a gadolinium-enhanced MRI measured all contrast-enhancing lesions. The products of the 2 greatest perpendicular diameters of all lesions were calculated and totaled, providing a baseline evaluation. As was common practice in this and other clinical trials carried out at this time the tumor measurements were based on contrast-enhanced lesions, but the overall tumor size was also measured including T2 and FLAIR images.8,9 Positron emission tomography (PET) scans were performed to differentiate between tumor progression, pseudoprogression, and treatment necrosis.10 The baseline provided the reference for determining response outcomes to the treatment. Blood and urine tests, complete blood count (with differential), platelet count, reticulocyte count, and standard serum chemistry, anticonvulsant serum levels, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time were evaluated before start to establish the normal baseline. The initial pretreatment measurements included KPS, vital signs, clinical disease status, demographics, medical history and current medications, physical examination with neurological emphasis, and chest x-ray. Toxicity is evaluated according to the Common Terminology of Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE v3.0). During the patient’s transition to home-based therapy administration, clinic staff made daily telephone contact for the first 2 months to ensure protocol compliance, to resolve any issues with therapy administration, and to continue assessing toxicity. Weekly contact was made starting from the third month, on the basis of which continuation of patient treatment with ANP was determined on a weekly basis depending on the trial protocol, patient health status, and the response to treatment.

Medications that were considered necessary for the patient’s welfare and that did not interfere with the evaluation of treatment were given at the discretion of the investigator.

During his lengthy course of treatment, the patient continued to take dexamethasone, which he had been prescribed before coming to the clinic. His initial dose of dexamethasone was 16 mg orally daily, which was increased to 24 mg daily in the second week of treatment. The gradual tapering of the dosage of dexamethasone back to 16 mg daily began a month later. There was further gradual reduction in dose resulting in 6 mg daily 6 weeks later, and 4 mg daily for the next 6 weeks. Over the remainder of the year this gradual reduction in dose continued with 0.5 mg daily being administered in May 2011. Dexamethasone was finally discontinued on June 22, 2001. Summary of treatment with ANP and dexamethasone is provided in Table 3.

For seizure control the patient was taking phenytoin, divalproex sodium, lamotrigine, and levetiracetam. The immunosuppression that developed after prior treatments and that resulted in occasional infections required various antibiotics during this time: ciprofloxacin, cephalexin, amoxicillin, clindamycin ophthalmic solution, dapsone, and acyclovir. He was also taking ranitidine, baclofen, acetaminophen, loperamide, polyethylene glycol, levothyroxine, calcium and potassium supplements, sodium bicarbonate, folic acid, and vitamin D.

RESULTS

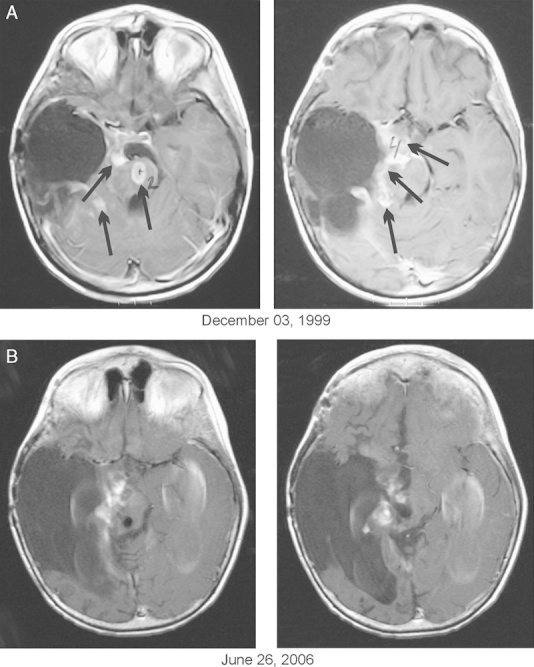

The patient’s progress was evaluated by MRI and PET. His baseline MRI on December 3, 1999 revealed multiple contrast-enhancing nodules located in the pons, cerebellum, both hemispheres, and leptomeninges. A pontine lesion occupied 82% of pons on T2-weighted axial image and enhancing portion measured 1.0×1.6 cm. The right quadrigeminal lesion measured 2.2×5.2 cm and the largest cerebellar nodule 1.0×2.0 cm. Baseline PET scan on November 5, 1999 revealed a hypermetabolic area encasing the right cerebellar hemisphere. The disease progression at baseline was confirmed by independent external radiologists not associated with BC. The impact of RT and chemotherapy was seriously considered in relation to disease progression and possible pseudoprogression. The initial GK procedure to the residual tumor was performed 9 months before baseline, and RT to the tumor bed was completed 7 months before commencing the treatment. In the intervening period, there was clear evidence of massive disease progression as shown by 4 MRIs and 1 PET scan. At least 8 major areas of tumor involvement developed, including the pons and leptomeninges, and almost all of them were outside of the RT fields. Additional GK procedure was delivered to the brainstem area approximately 1 month before commencing the treatment, but since then there had been further progression both in the pons and in the other areas.

High-dose chemotherapy and stem cell rescue resulted in initial decrease of the primary tumor size, but it was followed by massive progression shortly thereafter, as indicated by the MRI of August 19, 1999. TMZ failed to produce a response, which was documented by 2 consecutive MRIs, and TMZ was then discontinued by the treating neurooncologist. The patient presented with widely disseminated disease, and most of the lesions were outside the field of his prior RT, and occurred after chemotherapy.

MRIs were repeated periodically approximately every 8 weeks during the first 2 years of treatment, quarterly during the third to fifth years, and then annually. The multiple lesions visible on MRI were difficult to measure because of their irregular shape and infiltrative nature. PET scans were also performed to follow-up metabolic activity of the lesions. The scans were routinely evaluated by external radiologists, but on 3 occasions they were admitted for central radiology review (CRR). A partial response (PR) was determined by the CRR on June 19, 2000, and a complete response (CR) was confirmed on September 26, 2000 on the basis of an MRI scan performed on August 22, 2000 and a PET scan on August 25, 2000. It was the opinion of the CRR that the areas of enhancement in the primary tumor bed and in the prepontine area were not metabolically active, and were attributed to prior treatment (RT and GK). By MRI criteria there had been a decrease of contrast-enhancing lesions by >53% after 1 year and 4 months of treatment, and >70% by June 26, 2006. A PET scan carried out in April 2000 and repeated scans in August 2000, January 2001, and July 2006 did not show any hypermetabolic lesions, indicating a CR (Fig. 1). The BT-22 protocol permits determination of CR even though the patient has continued with a reduced physiological replacement dosage of corticosteroids, which is consistent with current standards of evaluation and response.9 Taking this under consideration and the opinion of the CRR, a CR was determined on August 25, 2000 (the date of the negative PET scan) despite the fact that dexamethasone was discontinued on July 22, 2001.

FIGURE 1.

A, Baseline magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). B, Follow-up MRI indicating partial response. Axial T-1 contrast-enhanced images. A complete response was confirmed by positron emission tomography scans. Arrows indicate contrast enhanced nodules.

During the course of ANP treatment the patient demonstrated a marked improvement in his condition. When evaluated on October 6, 2000, although he continued to have visual deficit in the left eye there was no nystagmus. There was persistent involvement of the eighth and fifth cranial nerves, but the rest of the cranial nerves were grossly intact. The patient continued to have left hemiparesis with significant adiadochokinesis and difficulty with finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin test on the right. He remained unable to perform those tests on the left. Deep tendon reflexes were hyperactive on the left and decreased on the right 2/5. Babinski sign was positive on the left and negative on the right. His KPS at this time was 50. He had continuous improvement in the following years. By January 2008 his KPS had increased to 80. At the time of this report (May 2013), the patient is in good health. He became a scout earlier this year, and he is currently taking 1 college course. His OS and PFS survival is >13 years.

The patient had the following adverse events: grade 1 fatigue, xerostomia and urinary urgency, grade 2 diarrhea, incontinence and urine color change, and grade 4 hypernatremia. The toxicities were easily reversible, and there was no chronic toxicity.

The preexisting toxicities gradually improved and did not reoccur during the treatment. Toxicities possibly related to treatment were xerostomia, urinary urgency, and incontinence, with the last 2 possibly related to the intravenous administration of ANP A10, which has increased osmolality. They were controlled by oral hydration and occasional reduction of the flow rate of the pump. The fatigue occurred after the parents misprogrammed the pump, which delivered a higher dose of ANP AS2-1 (not exceeding the daily maximum), and this resolved spontaneously the next day. On 2 occasions the color of the urine became light green, but such change did not last longer than a day and was asymptomatic. The patient had several episodes of grade 2 diarrhea when he was taking ANP A10 and AS2-1 capsules, which were controlled by changes to the diet and medications that did not require prescriptions. Grade 4 hypernatremia required hospitalization for 2 days and administration of intravenous fluids, but it resolved without complications.

DISCUSSION

In this report we describe an interesting and very rare case of pediatric recurrent GS involving the pons. The patient was initially diagnosed with LGA, which was successfully controlled for 4 years. Subsequently, his brain tumor transformed into a highly malignant GS, which took a very aggressive course. The patient received multiple treatments as previously described.

It is important to note that the patient’s pathology diagnosis of GS was subject to review by 3 different independent pathologists. For various reasons described in the text, the treating neurooncologist accepted, as the final diagnosis, the opinion of the first consulting neuropathologist (Table 2) as these included IHC studies. The diagnosis of GS and the extremely aggressive course of the disease was established by an experienced neuropathologist and confirmed by IHC.

During his treatment with ANP, the patient’s tumor stabilized then decreased and ultimately did not show any metabolic activity. Notably, the patient’s response was evaluated by periodic MRI and PET scans, which were evaluated by an outside radiologist with responses confirmed by the CRR. It was postulated that the patient has remained in CR since August 25, 2000.

Regarding the adverse drug events reported and their management, before admission to BC, the patient suffered immunosuppression and recurrent infections. For this reason he had been treated with numerous antibiotics and supplements before admission to BC. For a long time he was taking dexamethasone to reduce peritumoral edema and antacids to counteract side effects of corticosteroid adverse events. The adverse events observed before ANP treatment gradually improved during ANP administration, and were no longer present even though the patient continued ANP therapy. For this reason, it was felt that they were not related to ANP. His neurological deficit was also preexistent. During the course of ANP treatment a number of grade 1 and grade 2, reversible toxicities have been reported, which resolved without sequelae. He had only a single incident of grade 4, reversible toxicity from ANP consistent with hypernatremia, and did not exhibit any chronic toxicity. His condition gradually improved and currently he complains only of residual neurological deficit from his operations. Although it might be postulated that the GK procedures contributed to his response, we would argue that this is very unlikely, as he had developed multiple tumors and his tumors, which were not treated by GK, were already radio-resistant.

Newly diagnosed pediatric GS typically occurs in cerebral hemispheres and is treated with total surgical resection, standard RT, followed by chemotherapy.3,4 Survival after total surgical resection without RT and chemotherapy is usually <6 months, but OS after RT and chemotherapy can extend to slightly over 2 years,3,4 making this case study’s report of OS and PFS of >13 years of significant clinical interest. The benefit of TMZ has not yet been established.11 There are no reports of successful treatment modalities for pediatric recurrent and disseminated GS.

To our knowledge, pontine location of pediatric GS has not been previously described in the English-language medical literature. Such location combines the aggressiveness of GS with the grim prognosis of recurrent diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma. There are no effective treatments available for this condition, and median PFS is typically between 2 and 6 months.12–17 It is hoped that the planned genomic study will provide data that will link genetic abnormalities to the remarkable response in this case. The complete report on the BT-22 study and the report on the series of GS patients treated with ANP in phase II trials is currently in preparation. The details of the preclinical and clinical studies and the mechanism of action of ANPs are available in the literature.6,18–20

The patient reported in this case study is currently able to live a normal life and is studying in college. His OS and PFS are in excess of 13 years. This report suggests, therefore, that it is possible to obtain long-term OS and PFS in a child suffering from highly aggressive recurrent GS. The results of phase II studies of ANP in primary malignant brain tumors and GS patients treated in all of our phase II trials, which are in preparation, will provide more data on the significance of this response.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the additional physicians involved in the care of the patient: Robert A. Weaver, MD and Eva Kubove, MD, and employees of the clinic involved in the preparation of the manuscript: Mohammad Khan, MD, Darlene Hodge, Carolyn Powers, and Adam Golunski. Editorial assistance was provided by Malcolm Kendrick, MD.

Footnotes

The clinical trial was sponsored by the Burzynski Research Institute Inc.

S.R.B. is chairman of the Board of Directors and President of BRI Inc. G.S.B. is a member of the Board of Directors of BRI Inc.T.J.J. is the Vice President of Clinical Trials at BRI Inc. All authors are employed by Burzynski Clinic.

REFERENCES

- 1.Reis RM, Konu-Lebleblicioglu D, Lopes JM, et al. Genetic profile of gliosarcomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:425–432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sturm D, Witt H, Hovestadt V, et al. Hotspot mutations in H3F3A and IDH1 define distinct epigenetic and biological subgroups of glioblastoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:425–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karremann M, Rausche U, Fleischhack G, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of pediatric gliosarcomas. J Neurooncol. 2010;97:257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Salvati M, Lenzi J, Brogna C, et al. Childhood’s gliosarcomas: pathological and therapeutical considerations on three cases and critical review of the literature. Childs Nerv Syst. 2006;22:1301–1306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neelima R, Abraham M, Kapilamoorthy TR, et al. Pediatric gliosarcoma of thalamus. Neurol India. 2012;60:674–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burzynski SR. The present state of antineoplaston research (1). Integr Cancer Ther. 2004;3:47–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burzynski SR. Treatment for astrocytic tumors. Pediatr Drugs. 2006;8:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wen PY, Macdonald DR, Reardon DA, et al. Updated response assessment criteria for high-grade gliomas: response assessment in Neuro-oncology Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1963–1972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weller M, Cloughesy T, Perry JR, et al. Standards of care for treatment of recurrent glioblastoma—are we there yet? Neuro-oncol. 2013;15:4–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verma N, Cowperthwaite MC, Burnett MG, et al. Differentiating tumor recurrence from treatment necrosis: a review of neuro-oncologic imaging strategies. Neuro-oncol. 2013;15:515–534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Han SJ, Yang I, Tihan T, et al. Primary gliosarcoma: key clinical and pathologic distinctions from glioblastoma with implications as a unique oncologic entity. J Neurooncol. 2010;96:313–320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lashford LS, Thiesse P, Jouvet A, et al. Temozolomide in malignant gliomas of childhood: a United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group and French Society for Pediatric Oncology Intergroup study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4684–4691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreyer ZE, Kadota RP, Stewart CF, et al. Phase 2 study of idarubicin in pediatric brain tumors: Pediatric Oncology Group study POG 9237. Neuro-oncol. 2003;5:261–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren K, Jakacki R, Widemann B, et al. Phase II trial of intravenous lobradimil and carboplatin in childhood brain tumors: a report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;58:343–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fouladi M, Nicholson HS, Zhou T, et al. A phase II study of the farnesyl transferase inhibitor, tipifarnib, in children with recurrent or progressive high-grade glioma, medulloblastoma/primitive neuroectodermal tumor, or brainstem glioma: a Children’s Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2007;110:2535–2541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gururangan S, Chi SN, Young Poussaint T, et al. Lack of efficacy of bevacizumab plus irinotecan in children with recurrent malignant glioma and diffuse brainstem glioma: a Pediatric Brain Tumor Consortium study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3069–3075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minturn JE, Janss AJ, Fisher PG, et al. A phase II study of metronomic oral topotecan for recurrent childhood brain tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;56:39–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burzynski SR.Yang AV. Targeted therapy for brain tumors. Brain Cancer: Therapy and Surgical Interventions (Horizons in Cancer Research). 2006.New York: Nova Science Publishers Inc.;77–111 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burzynski SR, Janicki TJ, Weaver RA, et al. Targeted therapy with antineoplastons A10 and AS2-1 of high-grade, recurrent, and progressive brainstem glioma. Integr Cancer Ther. 2006;5:40–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burzynski SR. Recent clinical trials in diffuse intrinsic brainstem glioma. Cancer Ther. 2007;5:379–390 [Google Scholar]