Abstract

This article analyzes the sociodemographic network characteristics and antecedent behaviors of 119 lone-actor terrorists. This marks a departure from existing analyses by largely focusing upon behavioral aspects of each offender. This article also examines whether lone-actor terrorists differ based on their ideologies or network connectivity. The analysis leads to seven conclusions. There was no uniform profile identified. In the time leading up to most lone-actor terrorist events, other people generally knew about the offender’s grievance, extremist ideology, views, and/or intent to engage in violence. A wide range of activities and experiences preceded lone actors’ plots or events. Many but not all lone-actor terrorists were socially isolated. Lone-actor terrorists regularly engaged in a detectable and observable range of activities with a wider pressure group, social movement, or terrorist organization. Lone-actor terrorist events were rarely sudden and impulsive. There were distinguishable behavioral differences between subgroups. The implications for policy conclude this article.

Keywords: forensic science, terrorism, terrorist behavior, lone-actor terrorism, lone-wolf terrorism, typology, motivation

This article analyzes the sociodemographic network characteristics and antecedent behaviors of lone-actor terrorists leading up to their planning or conducting a terrorist event. Previous research has examined the strategic qualities of lone-actor terrorists (CTA, 2011), perceptions of the threat posed by lone actors 1, the narratives that promote lone-actor terrorist events 2, lone-actor terrorist attack characteristics and impacts 3, and individual case studies (for example 4–6). This research marks a departure from that domain because it largely focuses upon behavioral aspects of each offender.

This paper also examines differences between subgroups of lone-actor terrorists. In the limited literature that currently exists, offenders tend to be depicted in a binary fashion; subjects either “are” or “are not” a lone-actor terrorist. Lone-actor terrorists are therefore typically treated in a homogeneous manner, an exception being Pantucci’s 7 typology. Anecdotally, however, there are a number of easily distinguishable differences in lone-actor terrorists’ characteristics, behaviors, and connectivity with other groups. Specifically, this article examines whether the characteristics and behaviors of lone-actor terrorists differ based on their ideologies, network connectivity, or level of operational success.

The questions explored in this study are the following:

What, if any, demographic characteristics define lone actors?

What ideologies are associated with lone-actor terrorist events?

To what extent are close friends and family or wider networks of coconspirators typically aware of the lone-actor terrorist’s intent to engage in terrorist-related offenses?

To what extent are coconspirators typically involved in the planning stages of the offender’s intended terrorism-related activities?

How socially isolated do lone-actor terrorist offenders tend to be?

Is there a significant difference between lone offenders and those who commit terrorism-related offenses on behalf of a group?

Are there key life history events that may be relevant in understanding the development of lone actors?

Are there differences between lone-actor terrorists based on their ideology or network connectivity?

Method

Sample

The sample includes 119 individuals who engaged in or planned to engage in lone-actor terrorism within the United States and Europe and were convicted for their actions or died in the commissioning of their offense. For the purposes of this project, terrorism is defined as the use or threat of action where the use or threat is designed to influence the government or to intimidate the public or a section of the public, and/or the use or threat is made for the purpose of advancing a political, religious, or ideological cause. Terrorism can involve violence against a person, damage to property, endangering a person’s life other than that of the person committing the action, creating a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public, or facilitating any of the above actions. In addition to including individuals who actively planned and conducted violent attacks, our sample includes lone actors who engaged in nonviolent behaviors that facilitated or encouraged violent actions carried out by others or behaviors that intended to cause only structural damage. For example, some may prioritize causing infrastructural damage as in the case of isolated dyad Ellis Edward Hurst and Joseph Martin Bailie. Both men held grudges against tax authorities and planned to blow up a United States Internal Revenue Service building in December 1995. They decided to plan the detonation for a Sunday evening to ensure the building would be empty. Despite the 100lb IED failing to detonate due to a faulty fuse, the timing and delivery of the IED itself shows rational strategic thought on behalf of the perpetrators, who sought not to cause human injury but rather engage in an expressive act against a symbolic target. Other examples include Ryan Gibson Anderson and Kevin Gardner, who separately aimed to provide insider knowledge of U.S. and U.K. military capabilities and Army Camp weaknesses to wider terrorist networks.

The sample includes individual terrorists (with and without command and control links) and isolated dyads in our actor database. Individual terrorists operate autonomously and independently of a group (in terms of training, preparation, and target selection, etc.). In some cases, the individual may have radicalized toward violence within a wider group but left and engaged in illicit behaviors outside of a formal command and control structure. Individual terrorists with command and control links on the other hand are trained and equipped by a group—which may also choose their targets—but attempt to carry out their attacks autonomously. Isolated dyads include pairs of individuals who operate independently of a group. They may become radicalized to violence on their own (or one may have radicalized the other), and they conceive, develop, and carry out activities without direct input from a wider network. Although not technically “lone” actors, they are included for a number of reasons. First, a key component of this project focuses upon the network qualities of terrorists who are not members of terrorist groups. Second, an initial review of our cases showed that isolated dyads often formed when one individual recruited the other specifically for the terrorist attack. The formation of a dyad, in some cases, may be a function of the type of terrorist attack planned. Finally, by including these cases, it added to our sample, making the types of inferential statistics used later more applicable.

Prior to data collection, the authors examined the academic literature on lone-actor terrorism and built an actor dictionary, producing a list of names that fit the above criteria. Further names were also sourced through tailored search strings developed and applied to the LexisNexis “All English News” option. More individuals were also identified through the Global Terrorism Database developed by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) and lists of those convicted of terrorism-related offenses in the United Kingdom and the United States. The decision was then made to limit the population to post-1990 events because a large component of our data would be coded from the LexisNexis archive which is generally quite sparse before the 1990s. In total, 119 lone-actor terrorist offenders fit the specified geographical, temporal, and operational criteria.

Data Collection and Analysis

The codebook used in this project was developed based on a review of literature on individuals who commit a wide range of violent and nonviolent crimes, are victimized, and/or engage in high-risk behaviors as well as a review of other existing codebooks used in the construction of terrorism-related databases. The variables included in the codebook spanned sociodemographic information (age, gender, occupation, family characteristics, relationship status, occupation, employment, etc.), antecedent event behaviors (aspects of the individual’s behaviors toward others and within their day-to-day routines), event-specific behaviors (attack methods, who was targeted), and postevent behaviors and experiences (claims of responsibility, arrest/conviction details, etc.).

The authors collected data on demographic and background characteristics and antecedent event behaviors by examining and coding information contained in open-source news reports, sworn affidavits, and when possible, openly available firsthand accounts. The vast majority of our sources came from tailored LexisNexis searches. The authors also analyzed relevant documents across online public record depositories such as documentcloud.org, biographies of five lone actors in our sample (Ted Kaczynski, Timothy McVeigh, David Copeland, Eric Rudolph and Bruce Ivins) and all available scholarly articles.

Each observation was coded by three independent coders. After an observation was coded, the results were reconciled in two stages (coder A with coder B, and then coders AB with C). In cases when three coders could not agree on particular variables, the project’s postdoctoral research fellow resolved differences based on an examination of the original sources that the coders relied upon to make their assessments. Such decisions factored in the comparative reliability and quality of the sources (e.g., reports that cover trial proceedings vs. reports issued in the immediate aftermath of the event) and the sources cited in the report. Due to time constraints, no efforts were made to check the veracity of reporting against primary sources unless they were readily available online.

It is important to emphasize some limitations inherent in the sources used in this study. First, the sample only includes information on individuals who planned or conducted incidents reported in the media. It is possible incidents were missed that either (i) led to convictions but did not register any national media interest but may have been reported in local level sources not covered in the LexisNexis archives or (ii) were intercepted or disrupted by security forces without a conviction being made. Second, as the level of detail reported varied significantly across incidents, data collection was limited to what could reasonably be collected for each case. For example, Pennsylvania state police seized raw explosives and homemade IEDs in a 34-year-old man’s home in Milesburg, PA in December 2011. This received no national coverage. Finally, it is often difficult to distinguish between missing data and variables that should be coded as a “no”. Given the nature of newspaper reporting, it is unrealistic to expect each biographically oriented story to contain lengthy passages that list each variable or behavior the offender did not conduct (e.g., the offender was not a substance abuser, a former convict, recently exposed to new media, etc.). For the descriptive analysis that follows, where possible, the authors report or distinguish between missing data and “no” answers, but it should be kept in mind that the likely result is that “no” answers are substantially undercounted in the analysis. In the comparisons among lone actors based on their ideologies or network connectivity, each variable is treated in the analysis dichotomously (e.g., the response is either a “yes,” or not enough information to suggest a yes). Unless otherwise stated, each of the below reported figures are of the whole sample (119 individuals).

Despite these limitations, open-source accounts can provide rich data. This has been demonstrated in other studies focusing upon the sociodemographic characteristics, operational behaviors and developmental pathways of members of formal terrorist organizations. While this study has a wider remit and includes nonincident-related behaviors, given the particularly low base rate of lone-actor terrorism, the volume of reporting tends to be much higher compared to campaigns of violence where trials and convictions are a weekly occurrence. For example, educational data are accountable for 65% of our lone-actor sample. This is compared to <10% of Gill and Horgan’s 8 sample of Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) militants, for whom level of education could generally only be inferred from the individual’s occupational status.

Results

Overall Characteristics and Behaviors

Gender

Our lone-actor terrorist sample is heavily male-oriented. In total, 96.6% are male and there are only four instances of females engaging in such behaviors. The figure of 3.4% being female closely resembles studies that focus upon membership profiles of terrorist organizations/networks. For example, women accounted for 4.9% of a sample of 1240 members of the PIRA 9, 2.7% of a sample of 222 dissident Irish Republicans 8, and 6.4% of Reinares’ 10 sample of ETA members from 1970 to 1995. There is an ongoing debate about the nature of female recruitment and the roles women typically engage in within terrorist groups 11. Much of this debate concerns the relative degree to which women typically conduct behaviors that are supportive of and facilitate violence as opposed to actually committing front line violent activities. In terms of our female subset, there is also such a distinction. Two of the females in our sample committed violent acts. Roshonara Choudhry stabbed a Labour Party MP, Stephen Timms, in May 2010 in revenge for supporting the Iraq War and the subsequent deaths of innocent people within Iraq. Rachelle “Shelley” Shannon shot Dr. George Tiller (who was later assassinated by lone actor Scott Roeder) outside his abortion clinic in Kansas in 1993. Shannon was also found guilty on 30 counts of being connected to several arson attacks against a total of nine abortion clinics. The other two females engaged in facilitative behaviors. For example, Shella Roma was convicted in March 2009 of disseminating terrorist publications. She produced two versions of a leaflet entitled, The Call, which encouraged individuals to commit terrorist acts against Western forces. The intention was to distribute these leaflets both from her home and outside of particular mosques near her home in Oldham, England. Houria Chahed Chentouf was also convicted in 2009 in the United Kingdom for possessing documents likely to be useful for potential terrorists. She was stopped at Liverpool’s John Lennon airport with USB stick containing more than 7000 files including instructions on how to set up training camps and manufacture IEDs as well as a list of potentially suitable targets. Investigators also later found hand-written documents that suggested Chentouf was considering moving from facilitative to violent actions. The documents apparently considered whether she and her children should become suicide bombers 12.

Age of First Terrorist Activity

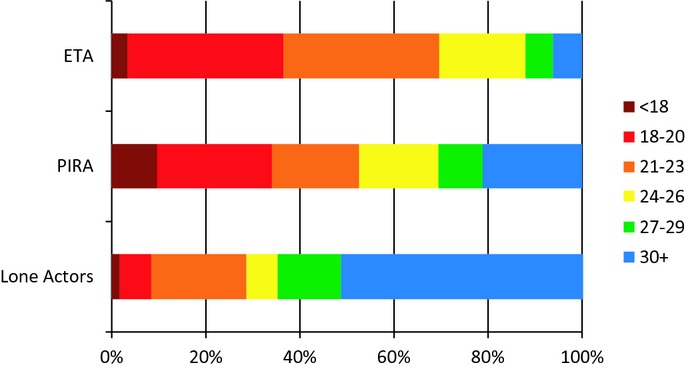

Figure 1 below examines the age at which offenders committed their first terrorism-related activity that led to a subsequent arrest and conviction unless the offender died in the course of the terrorist event itself. Offender’s age ranged from 15 to 69, with a mean of 33, a mode of 22, and a standard deviation of 12. This average age is much older than studies that have focused upon Colombian militants—average age of 20 13, the PIRA—average age of 25 14, and finally al-Qaeda-related terrorists—average age of 26 15. In fact, it is the second oldest sample of terrorists that the authors are aware of, behind a sample of contemporary dissident Irish republicans—average age of 35 8. Many in the dissident sample had previously been members of PIRA, however, suggesting that their average age of first terrorist involvement would be younger.

Figure 1.

Age when committing first terrorism-related offense that resulted in conviction.

Figure 1 compares the lone-actor data set with data on PIRA and the Basque separatist group Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) in terms of the relative distribution of age groups. These groups were chosen because they are the sole studies with comparable and available data. The percentage of those over 30 years of age in our sample of lone actors is substantially larger than in the two other samples for which comparative figures are available. It is almost two and a half times larger than in the PIRA sample and more than eight times larger than in the ETA sample. The proportion of those under the age of 20 is also approximately four times smaller than in the ETA and PIRA samples. As depicted in Fig. 1, those between 21 and 23 years of age and those over 30 encompass more than 70% of the lone actors in the sample, suggesting that the onset of lone-actor engagement in terrorism has a different temporal trajectory than that of engaging in terrorism within formal groups.

Relationship Status and Family Characteristics

Of the 106 individuals for whom relationship status data were available, 50% were single individuals who had never married. A few (6.6%) were in relationships but had not yet married. Almost a quarter (24.5%) were married, and a further 18.9% had either separated from their spouse (3.8%) or were divorced (15.1%). The percentage of married individuals in this sample is lower than that associated with al-Qaeda-related terrorists (73%) 14, PIRA (41.6%) 13, and contemporary dissident republicans (50%) 8, but higher than that associated with ETA (11.6%) 10 and Pakistani militants (14%) 16. Given the relatively older age of this sample, the marriage rates are low. When we consider the oft-cited finding that criminal offending decreases as individuals age due to biographical constraints such as marriage, it is also not surprising to find such a comparatively older sample to have a high proportion of unattached individuals.

Just more than a quarter (27.7%) had children, 34.5% were reported not to have children, and in 37.8% of cases, data on children were unreported. This figure is comparatively much lower than Gill and Horgan’s 14 study of PIRA militants in which 41.4% had children, especially when we take into consideration that the lone-actor sample is a much older cohort of individuals.

Of the 65 observations on which parental relationship status was available, 47.7% were married, while the remainder were divorced (30.8%), separated (7.7%), widowed (7.7%), or never married (3.1%).

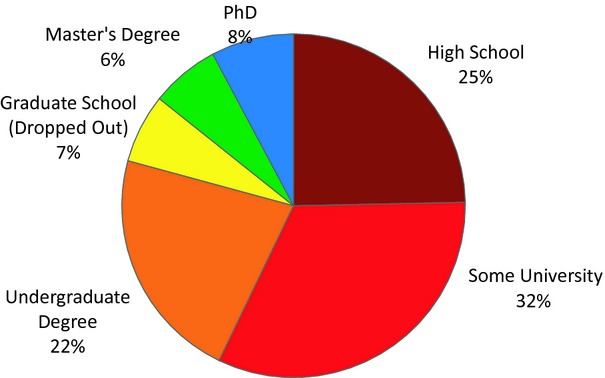

Education

This section outlines the distribution of educational achievement among members of the sample for which data were available (77 individuals). In total, approximately a quarter’s (24.7%) highest educational achievement was either attending or completing high school or secondary education. A further 32.5% either attended a community college, trade school, or university undergraduate education without graduating. An additional 22.1% completed some form of community college, trade school, or university education and graduated. Another 20.8% participated in graduate school and either failed to graduate (6.5%), graduated with a master’s degree (6.5%), or graduated with a doctoral degree (7.8%). In sum, there is a generally even distribution across the spectrum of educational achievement (depicted in Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Highest educational achievement.

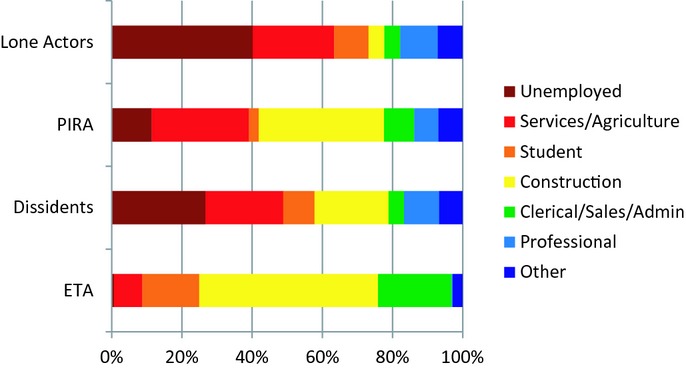

Employment

Despite the generally high educational achievement among our cohort, this was not immediately apparent when viewing the types of employment they were in at the time of their terrorism-related activity. Employment data were available for 112 of the sample. Of these individuals, 40.2% were unemployed and a further 9.8% were still students. The other half of the sample were employed but mainly concentrated within the service industry (23.2%). Much smaller percentages were in professional occupations (10.7%), construction (4.5%), clerical/administrative/sales positions (4.5%), and agriculture (1.8%). These figures are largely different from the studies cited earlier on PIRA and ETA as well as Horgan and Morrison’s 17 study of dissident republicans particularly in terms of those unemployed and those in the construction industry (see Fig. 3). In both the PIRA and ETA samples, the construction industry was the largest employer. PIRA and ETA were comprised of comparatively fewer unemployed individuals compared to the lone-actor terrorist data set.

Figure 3.

Comparative occupational category breakdown.

Military Experience

A quarter (26%) had military experience. Of this subset, 76.7% had since left the army, the vast majority of whom for normal reasons. Some, however, had been ejected from the army for various offenses (such as racist behavior in the case of Sean Gillespie), and others had been suspended and faced court-martial (such as Naser Jason Abdo on child pornography charges). Of those who had military experience, 23.3% had actual combat experience.

Criminal and Other Illicit Activities

Significantly, 41.2% of the sample had previous criminal convictions, and this figure is far higher than what is anecdotally suggested regarding members of formal terrorist organizations, who prefer recruits with clean records as they are unlikely to raise red flags among the security community. Offenses included threats to life, first-degree robbery, criminal damage, custodial and second-degree assault, firearms offenses including possession, obstructing law enforcement officers, drunk driving, grand larceny, vehicle theft, blackmail, lewd and disorderly conduct, drug possession, counterfeiting, criminal use of explosives, vandalism, attempted murder, child neglect, restraining order violations, theft, income tax issues, child pornography possession, graffiti, and somewhat strangely “possession of a carcass of a protected barn owl”. Of this subset, 63.3% served time in jail. During jail time, at least 32.3% of this subset adopted the ideology and radicalized (as reported in open-source news articles) for the event they later conducted or planned. Of the full sample, 37.8% had previously engaged in violent behaviors. More than a fifth (22.7%) had a history of substance abuse. At least 27.3% had no previous convictions or history of imprisonment.

Mental Health

Just less than a third (31.9%) had a history of mental illness or personality disorder. In the vast majority of these cases, the diagnosis had been made before the individual engaged in terrorism-related activities. Naveed Afzal Haq, for example, had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Of this cohort, many were prescribed medicine, others were committed into residential programs and psychiatric institutions, others were hospitalized, and some engaged with counseling services. Some lone actors were only diagnosed upon their arrest and subsequent trial (for example, Ted Kaczynski was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia).

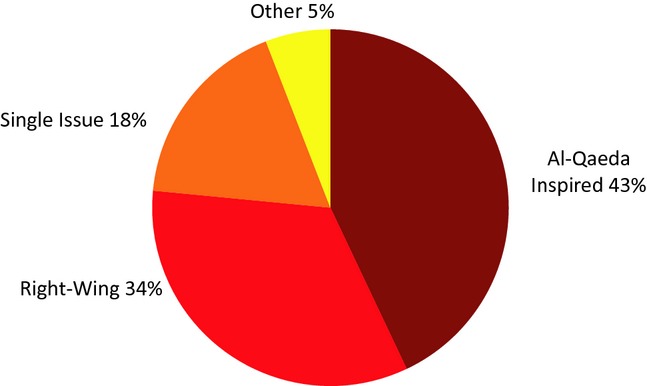

Ideological Justifications

As Fig. 4 illustrates, the lone-actor terrorists in our sample had a range of ideologies. Religiously inspired lone actors constitute the largest set of actors at 43%. This is perhaps not a surprising finding given how loosely connected al-Qaeda’s transnational network has become over time and al-Qaeda’s growing emphasis upon lone-actor attacks (for example, al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula’s Inspire magazine has been a consistent advocate of this strategy). Those inspired by right-wing ideologies constitute the second largest group representing a third of the total sample. The third largest grouping is a clustering of individuals driven by single-issue causes such as antiabortion or environmental campaigning. The balance between these groups has changed over time. Only 7.8% of religiously oriented lone actors engaged in their terrorist actions before 2001, whereas the corresponding figures for right-wing extremists is 32.5% and single-issue offenders is 47.6%.

Figure 4.

Lone-actor ideological orientation.

Historically, there have been very few lone-actor incidents involving left-wing or nationalist inspired individuals. For four of our cohort, it was extremely difficult to categorize the individual’s ideological orientation and motivation. This is either because the individual’s ideology was self-made (as in the case of Ted Kaczynski) or economically oriented (as in the case of Dwight Watson and arguably Bruce Ivins).

Awareness of Intentions

In most cases, other individuals knew something concerning some aspect of the offender’s grievance, intent, beliefs, or extremist ideology prior to the event or planned event. In 58.8% of cases, the offender produced letters or public statements prior to the event outlining his/her beliefs (but not necessarily his/her violent intent). This figure aggregates both virtual and printed statements in newspapers and leaflets, etc. In 82.4% of the cases, other people were aware of the individual’s grievance that spurred the terrorist plot, and in 79%, other individuals were aware of the individual’s commitment to a specific extremist ideology. In 63.9% of the cases, family and friends were aware of the individual’s intent to engage in terrorism-related activities because the offender verbally told them. This is comparatively lower figure than the 81% found in a study of school shooters 18. In 65.5% of cases, the offenders expressed a desire to hurt others. This desire was communicated through either verbal or written statements. These findings suggest therefore that friends and family can play important roles in efforts that seek to prevent terrorist plots. Of those who were married or in a relationship, 24.2% of the offenders’ spouses or partners were members of a wider network associated with the ideology that inspired the lone-actor terrorist. Finally, in 22.7% of the cases, the individual provided a specific preterrorist event warning.

There is also much evidence to suggest that others were aware of the individual’s disposition, but not necessarily their intent. In 53.8% of the cases, the offender was characterized by close friends/family as an angry individual. Of this subsample (64 individuals), there is a suggestion that the offender’s anger was noticeably increasing in 62.5% of the cases.

Pre-Event Behaviors

This section provides an overview of our findings concerned with the behaviors the individual engaged in prior to the terrorist event or planned event. A fifth (20.2%) of the total sample converted to a religion before engaging or planning to engage in an event. Not all of those who converted were necessarily religiously motivated offenders, however. Some, such as Leo Felton, were motivated by right-wing ideologies. Others, such as James Kopp, were single-issue offenders. Of the al-Qaeda-inspired offenders, religious converts account for 37.3%. The religiosity of 29.4% of the al-Qaeda-inspired lone-actor terrorists noticeably increased in the buildup to their terrorist event or planned event.

Half (50.4%) changed address within the 5 years prior to their terrorist event planning or execution. Significantly, of those who did change address, 45% did so within 6 months of their eventual terrorist attack or arrest. A further 20% changed address between seven and twelve months prior to the terrorist event or preemptive arrest. Altogether, this means that just less than a third of our total sample (32.8%) changed address in the year before their terrorist plot either occurred or was prevented.

As noted earlier, 40.2% were unemployed at the time of their arrest or terrorist event. Many were chronically unemployed and consistently struggled to hold any form of employment for a significant amount of time. Of the unemployed subset, however, approximately a quarter (26.6%) had lost their jobs within 6 months and a further 15.5% between seven and twelve months before the event. On a related note, 25.2% experienced financial problems. Of this subsample (30 individuals), 56.6% experienced financial problems within a year of their terrorist attack or plot.

Many (32.8%) of the offenders were characterized as being under an elevated level of stress due to a number of reasons. Of this subsample, 74.3% of the cases of elevated stress occurred within a year of the terrorist attack or plot. Very few had recently (e.g., within 5 years) experienced a death in their family (6.7%) that may have served as a catalyst for the intended violence that followed. Very few dropped out of school or left university (10.1%) before their terrorist event or planned event. Approximately one in five of those lone actors in gainful employment demonstrated worsening work performance in the buildup to their terrorist event or plot. Very few (6.7%) were interrupted in working on a proximate goal in the year before their terrorist event or planned event. Some (12.6%) noticeably increased their physical activities and outdoor excursions in the buildup to their terrorist event. At least 15.1% subjectively experienced being the target of an act of prejudice or unfairness. On a related note, 19.3% subjectively experienced being disrespected by others, while 14.3% experienced being the victim of verbal or physical assault. At least 25.2% of the full sample was characterized as suffering from long-term sources of stress.

Social Isolation

More than a quarter (26.9%) adopted their radical ideology when living away from home in another town, city or country. At least 37% lived alone at the time of their event planning and/or execution, a further 26.1% lived with others, and no data were available for the remaining cases. This is perhaps a surprisingly low figure considering that the vast majority of plots and preparations were carried out within the lone offender’s home. More than half (52.9%) were characterized as socially isolated by sources within the coded open-source accounts.

On occasion, lone-actor terrorists experienced problems with personal relationships. In these cases, social isolation was not a long-standing occurrence but instead was derived from more recent interpersonal conflict. For example, 31.1% experienced problems in close personal relationships (e.g., family, romantic relationships). Of this subsample (37 individuals), 32.4% experienced these difficulties within the 6 months prior to their terrorist attacks or plots. At least 10.9% of the full sample experienced being ignored or treated poorly by someone important to them in the buildup to their terrorist event or planned event. Additionally, 8.4% experienced someone important demonstrating that they did not care about the individual in the buildup to their offense.

Behaviors Within a Wider Network

One in six (16.8%) sought legitimization from religious, political, social, or civic leaders prior to the event they planned. Perhaps the most famous case of this behavior is the case of Nidal Malik Hassan, who sent Anwar al-Awlaki at least 18 emails between December 2008 and June 2009 asking various questions concerning the legitimacy of killing innocents and when engaging in jihad is appropriate. A similar figure (14.3%) had previously engaged in fundraising or financial donations to a wider network of individuals associated with either licit pressure groups or illicit groups who espoused violent intentions.

Importantly, 33.6% of the sample had recently joined a wider group, organization, or movement that engaged in contentious politics. Many of these groups engaged in legal activities but shared similar ideologies to those the lone actor used to justify planning or conducting his/her terrorist activity. A similar number (31.9%) had also become recently exposed to new social movement or terrorism-related media.

Links to a Wider Network

Approximately a third of the sample (36.1%) had family members or close associates known to have been involved in political violence or criminality. Just less than half (47.9%) interacted face-to-face with members of a wider network of political activists, and 35.3% did so virtually. In 68.1% of the cases, there is evidence to suggest that the individual read or consumed literature or propaganda from a wider movement. There is evidence to suggest in 20 of the cases (16.8%) that there may have been wider command and control links specifically associated with the violent event that was planned or carried out.

One in ten of the sample had been either rejected or ejected from a wider network or group that engaged in legal contentious politics. Perhaps the most famous example is that of Timothy McVeigh, who had been ejected from various right-wing affiliated organizations such as the National Rifle Association.

In terms of the planning of the terrorist event itself, there is also much evidence that others were aware of the offender’s specific intent of engaging in terrorism-related activities. In approximately a third of the cases (34.5%), the lone actor had tried to recruit others or form a group prior to the event. In 57.7% of cases, other individuals possessed specific information about the lone actor’s research, planning, and/or preparation prior to the event itself. In nearly a quarter of all cases (23.5%), other individuals were involved in procuring weaponry or technology that was used (or planned to be used) in the terrorist event but did not themselves plan to participate in the violent actions. In 16 cases, other individuals helped the lone actor assemble an explosive device.

More than half of the lone actors (52.9%) characterized their actions as associated with a wider group or movement or claimed to be part of a wider group or movement while a much smaller figure (5.9%) framed their actions as driven by personal grievances. For many, this meant characterizing their actions as being associated with an established group such as al-Qaeda. Others, however, claimed their attacks on behalf of a group whose actual existence is highly questionable. For example, Ted Kaczynski’s letter to the New York Times claimed his group, called FC, was responsible for the bombing attacks. Similarly, no evidence has emerged within the open-source literature that the contemporary manifestation of the Knights Templar referenced by Anders Breivik actually exists.

Finally, at times, there appears to be a direct form of knowledge diffusion between lone actors within our sample. Evidence suggests that approximately a quarter (26.9%) read or consumed literature or propaganda concerning other lone-actor terrorists. Additionally, evidence also suggests that 15.1% consumed or read literature or propaganda produced by other lone-actor terrorists.

Attack and Plot Related Behaviors

Training for the plots typically occurred through a number of ways. Approximately a fifth of the sample (21%) received some form of hands-on training, while 46.2% learned through virtual sources. In approximately half the cases (50.4%), investigators found evidence of bomb-making manuals within the offender’s home or property. The fact that much strategic and tactical planning goes into lone-actor terrorist events is demonstrated by the finding that 29.4% of offenders engaged in dry runs of their intended activities (also as not all of the sample intended to engage in violence, this finding would likely be even higher if nonviolent offenders were excluded). Of those who did make dry runs or preparatory trips (35 individuals), 57.1% did so within a year of the eventual attack. Very few (4.2%) used drugs or alcohol in the commissioning of a terrorist attack.

In terms of plotting, 41.2% of the offenders specifically targeted, or intended to target, people, 11.8% targeted property, and a further 32.8% plotted against a combination of both target types. When we break down plots by the nature of the attack location, it is evident that the most commonly sought-after target were civilians (27.7%), followed by government-related targets (23.5%), businesses (17.6%), religious targets (e.g., mosques), (8.4%) and military targets (6.7%). Compared to statistics provided by Global Terrorism Database developed by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, lone-actor terrorists appear to plan or perpetrate attacks against military targets on a far less consistent basis compared to terrorist groups. This may be a function of capability. Most (58%) lone-actor terrorist plots are conceived to take place in public locations. In 24.4% of cases, the offender has had a previous history with the location of the attack (e.g., was previously employed there). Just less than a half (47.1%) of lone actors possessed a stockpile of weapons for the commissioning of the offense.

Just over half of the observations (51.2%) successfully executed their terrorist attack. Of this sample (n = 61), the majority of offenders (61.2%) used their personal vehicle to travel to the attack location, while others took public transport (16.1%), walked (9.6%), or rented a car (12.9%).

In 21% of the cases, the individual expressed remorse/regret following their event and subsequent arrest. Of these cases (25 individuals), 44% later changed their beliefs/ideological orientation. At least 16.6% expressed no remorse for their actions, and data were unavailable for the rest of the cases.

Comparing Subgroups of Lone-Actor Terrorists

The descriptive analysis of our data above illustrates that there is no reliable profile of a lone-actor terrorist. In this section, the authors examine specific subgroups of lone-actor terrorists to explore whether the individual characteristics and behaviors of lone-actor terrorists differ across these distinctions.

Comparing Lone-Actor Terrorists by Ideology

Terrorist groups are commonly distinguished across motivational and ideological domains 19–21. The three most prevalent ideologies held by members of our lone-actor terrorist data set were right-wing, single-issue (animal rights, antiabortion, environmentalism), and al-Qaeda-related ideologies. In Table 1, the major differences in individual characteristics and antecedent event behaviors associated with lone actors who held these ideologies are outlined. To identify differences between ideological groups, 2 × 2 chi-squared analyses (or Fisher’s exact tests where appropriate) were run for each ideological domain against each antecedent and behavioral variable (e.g., right wing vs. single issue/al-Qaeda). A one-way ANOVA comparison of means test was used for the average age variable.

Table 1.

Comparing lone actors across ideological domains.

| Right Wing (n = 40) | Single Issue (n = 21) | Al-Qaeda Related (n = 52) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Town size <20,000 | 37.5%*** | 28.6% | 9.6%*** |

| University experience | 15%*** | 52.4% | 50%** |

| Worked in construction | 12.5%*** | 0% | 0%** |

| Worked as a professional | 2.5%* | 14.3% | 11.5% |

| Student at time of event | 2.5%* | 4.8% | 17.3%** |

| Unemployed | 50%* | 38.1% | 30.8% |

| Verbal statements to friends/family about intent or beliefs | 52.5%** | 71.4% | 71.2% |

| Religious convert | 2.5%*** | 19% | 36.5%*** |

| Sought legitimization | 7.5%** | 9.5% | 28.8%*** |

| Lived away from home when ideology adopted | 15%** | 19% | 38.5%*** |

| Others helped procure weaponry | 10%*** | 33.3% | 32.7%* |

| Engaged in dry runs | 17.5%** | 47.6%** | 30.8% |

| Recently joined a wider group/movement | 47.5%** | 38.1% | 23.1%** |

| Evidence of command and control links | 5%** | 4.8% | 30.8%*** |

| Based in the United States | 52.5% | 71.4%*** | 28.8%*** |

| In a relationship | 20% | 52.4%*** | 21.2% |

| Previous criminal conviction | 50% | 61.9%** | 26.9%*** |

| Previously imprisoned | 27.5% | 47.6%** | 19.2%* |

| Provided a pre-event warning | 17.5% | 38.1%* | 21.2% |

| Spouse/partner part of a wider movement | 5% | 19%** | 3.8% |

| Learned through virtual sources | 37.5% | 19%*** | 65.4%*** |

| History of mental illness | 30% | 52.4%** | 25% |

| Others aware of individual’s planning | 52.5% | 38.1%** | 69.2%** |

| Children | 15%** | 42.9%* | 28.8% |

| University degree | 5% | 4.8% | 17.3%** |

| Average age | 36.3 years | 36.8 years | 26.7 years*** |

| Successful execution of terrorist attack | 57.5% | 66.7% | 40.4%** |

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

As the results suggest, there are distinctions among lone-actor terrorists with specific types of ideologies. The average age of al-Qaeda-related lone actors was 10 years younger than that of either the right-wing or single-issue cohorts. Members of this subgroup (compared to a combination of right-wing and single-issue lone actors) were also significantly more likely to be students or have a university degree and/or some experience of university. They were significantly less likely to have previous criminal convictions or experience of imprisonment at the time of their terrorist event. Given the ideological beliefs of this subgroup, it is also not surprising that they were significantly more likely to seek legitimization from religious, political, social, or civic leaders prior to their terrorist event or plot and significantly more likely to be religious converts. They were also significantly more likely to learn through virtual sources and to be living away from home during the phase when they adopted their extremist ideology. There was also a significantly higher indication of command and control links with this subgroup (mainly through others helping them procuring weaponry or through others knowing about the specific attack plan). Historically, al-Qaeda-related lone-actor terrorists have been significantly less likely to be U.S.-based compared to those espousing right-wing or single-issue ideologies. They have also been significantly less likely to join a wider pressure group or social movement in the buildup to their terrorist event and significantly less likely to successfully execute their terrorist attack.

Compared to both single-issue and al-Qaeda-inspired offenders, right-wing lone-actor terrorists were significantly less likely to have experienced any form of university education, work as a professional, be a student, be a religious convert, or be living away from home when they adopted their radical ideology or have children. They were more likely to be employed in construction at the time of their terrorist event, to be based in a town with a population smaller than 20,000, and to have joined a wider pressure group or social movement before their terrorist action. In terms of specific event planning activities, they were significantly more likely to solely obtain the weapons and technology needed for the event but also significantly less likely to engage in dry runs, display evidence of command and control links, make verbal statements to friends and family about their intent or beliefs, or seek legitimization for their intended action from epistemic authority figures.

Compared to both al-Qaeda and right-wing offenders, single-issue lone-actor terrorists were significantly more likely to be in a relationship (and to have a spouse involved in a wider movement of activist politics), have children, be based in the United States, have previous criminal convictions and have previously been imprisoned. More than half had a history of mental illness. They were also significantly more likely to engage in dry runs and provide pre-event warnings and far less likely to learn through virtual sources. Single-issue lone-actor terrorists were also significantly less likely to have others aware of their research, planning, or intent to engage in a terrorist attack.

There was very little to differentiate among these subgroups of lone-actor terrorists in terms of making verbal statements to a wider audience outside of their immediate friends and family or other people knowing about the individual’s grievance or extremist ideology prior to the event. There were also no differences in their histories of substance abuse, military engagement, and experiences of hands-on training; engagement with literature and propaganda (of a wider movement and of other lone actors); face-to-face interactions with members of a wider network; or possession of close associates involved in criminal activities.

Comparing Lone-Actor Terrorists by Network Connectivity

While comparing and contrasting lone-actor terrorists across ideological domains has revealed some interesting results, perhaps a more important comparison for the practitioner community is one that examines lone-actor terrorists based on how operationally connected they are to a broader network of activists. Depending upon the level of connectivity, different investigative strategies or disruption efforts may be necessary. Table 2 illustrates the statistically significant differences between individual terrorists without command and control links, and individual terrorists with command and control links and isolated dyads.

Table 2.

Comparing lone actors by network connectivity.

| Individuals Without Command and Control Links (n = 87) (%) | Individuals With Command and Control Links (n = 21) (%) | Isolated Dyads (n = 11) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Based in the United States | 55.2*** | 4.8*** | 36.4 |

| Previous military experience | 31*** | 4.8** | 9.1 |

| Previous criminal conviction | 47.1** | 19** | 36.4 |

| Held a PhD | 2.3 | 0 | 18.2** |

| Lived alone | 40.2 | 38.1 | 9.1** |

| Lived away from home when ideology adopted | 23 | 42.9* | 27.3 |

| Received training | 20.7 | 33.3 | 0* |

| Learnt through virtual sources | 40.2*** | 66.7* | 72.7* |

| History of mental illness | 35.6** | 19 | 9.1 |

| Socially isolated | 57.5* | 33.3* | 45.5 |

| Recently joined a wider group/movement | 27.6** | 47.6 | 45.5 |

| Noticeable increase in religiosity | 23*** | 61.9*** | 27.3 |

| Family/close associates involved in political violence/crime | 27.6*** | 57.1** | 63.6** |

| Interacted face-to-face with wider network | 39.1*** | 61.9 | 90.3*** |

| Interacted virtually with wider network | 28.7*** | 57.1** | 63.6* |

| Others helped procure weaponry | 17.2*** | 38.1* | 45.5* |

| Others helped build IED | 6.9*** | 33.3*** | 27.3 |

| Others aware of individual’s planning | 42.5*** | 100*** | 100*** |

| Attempted to recruit others | 27.6** | 33.3 | 81.8*** |

| Consumed propaganda from a wider movement | 65.5* | 85.7* | 72.7 |

| Al-Qaeda related | 33.3*** | 76.2*** | 63.6 |

| Single issue | 23** | 4.8* | 0 |

| Right wing | 39.1** | 9.5** | 36.4 |

| Successfully executed an attack | 57.5** | 33.3* | 27.3 |

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Compared to isolated dyads and those with command and control links, the results suggest that individuals without command and control links were more likely to have military experience, previous criminal convictions, be based in the United States, hold either single-issue or right-wing ideologies, be characterized as socially isolated, and have a history of mental illness. They were significantly less likely to learn through virtual sources, increase their religiosity before their event, recently join a wider pressure group or social movement, attempt to recruit others, or have family or close associates involved in political violence or crime. Unsurprisingly, compared to both those with command and control links and isolated dyads, those without command and control links were also significantly less likely to interact either face-to face or virtually with members of a wider network or have others aware of their planning, help build their IEDs, or help procure weaponry. They were also significantly less likely to be al-Qaeda inspired. They were also significantly more likely to successfully execute their terrorist attack.

Apart from network-related behaviors, there is little to differentiate between those with command and control links with those belonging to the other two subgroups. They were significantly more likely to have had others notice an increase in their religiosity and be inspired by al-Qaeda. They were significantly less likely to be influenced by right-wing or single-issue ideologies, be characterized as socially isolated, have previous criminal convictions, military experience, or be based in the United States. They were also significantly less likely to successfully execute their terrorist attack.

For isolated dyads, it is also largely the case that little separates them from the other two subgroups other than network-related behaviors. Compared to the other two subgroups, isolated dyads were significantly more likely to attempt to recruit others and hold a PhD. Isolated dyads were significantly less likely to receive hands-on training or live alone.

Comparing Successful and Foiled Lone-Actor Terrorists

This section outlines the significant differences between those lone-actor terrorists who successfully executed an attack and those who did not. To calculate whether differences were significant, chi-squared tests were used for each variable (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparing successful lone actors to intercepted lone actors.

| Did the Individual Successfully Commit an Attack? | Yes (n = 61) (%) | No (n = 58) (%) |

|---|---|---|

| University experience | 54.1*** | 24.1 |

| Socially isolated | 70.5*** | 34.5 |

| History of mental illness | 39.3* | 24.1 |

| Previously rejected from wider group | 16.4** | 3.4 |

| Other’s aware of research/planning or preparation for event | 36.1 | 79.3*** |

| Attempted to recruit others | 24.6 | 44.8** |

| Learnt through virtual sources | 29.5 | 63.8*** |

| Bomb-making Manuals in home | 31.1 | 70.7*** |

| Recently exposed to new media | 19.7 | 41.4*** |

| Interacted virtually with wider network | 24.6 | 46.6** |

| Read or consumed literature/propaganda from a wider movement | 52.5 | 84.5*** |

| Read or consumed literature/propaganda about other lone actors | 11.5 | 43.1*** |

| Read or consumed literature/propaganda of other lone Actors | 8.2 | 22.4** |

*p < 0.1; **p < 0.05; ***p < 0.01.

Interestingly, those who successfully committed an attack were significantly less likely to engage in a number of network-related behaviors including having other’s aware of their attack planning, attempting to recruit others, learning through virtual sources, possessing bomb-making manuals, being recently exposed to new media, interacting virtually with members of a wider network, and consuming/reading propaganda related to either a wider group or other lone-actor terrorists. Successful lone-actor terrorists, however, were significantly more likely to have university experience, be characterized as being socially isolated, have a history of mental illness, or have previously been rejected from a wider group or movement.

Discussion and Conclusion

This article focused on 119 lone-actor terrorists and the behaviors that underpinned the development and/or execution their plots. In total, seven key findings were identified. This section summarizes these findings and highlights their implications from a preventative and investigative perspective before concluding with a discussion of potential avenues for future research.

Findings and Implications

Finding 1: There was no uniform profile of lone-actor terrorists.

Although heavily male-oriented, there were no uniform variables that characterized all or even a majority of lone-actor terrorists. The sample ranged in age from 15 to 69. Half were single, 24% were married, and 22% were separated or divorced. Twenty-seven percent had children. Educational achievement varied substantially with approximately a quarter either having attended or finishing high school, approximately a third of the sample having attended, but not graduating from some form of university, 22% completing an undergraduate degree, and 21% having attended or finishing some form of graduate school. In total, 8% held a PhD, while 40% of the sample was unemployed at the time of their terrorist attacks or arrests, 50% held jobs (11% professional positions), and 10% were students. Twenty-six percent had served in the military. Finally, forty-one percent had previous criminal convictions, 31% had a history of mental health problems, and 22% had a history of substance abuse.

Thus, no clear profile emerged from the data. Even if such a profile were evident, however, an over-reliance on the use of such a profile would be unwarranted because many more people who do not engage in lone-actor terrorism would share these characteristics, while others might not but would still engage in lone-actor terrorism.

Finding 2: In the time leading up to most lone-actor terrorist events, evidence suggests that other people generally knew about the offender’s grievance, extremist ideology, views and/or intent to engage in violence.

For a large majority (83%) of offenders, others were aware of the grievances that later spurred their terrorist plots or actions. In a similar number of cases (79%), others were aware of the individual’s commitment to a specific extremist ideology. In 64% of cases, family and friends were aware of the individual’s intent to engage in a terrorism-related activity because the offender verbally told them. In 58% of cases, other individuals possessed specific information about the lone actor’s research, planning, and/or preparation prior to the event itself. Finally, in a majority (59%) of cases, the offender produced letters or made public statements prior to the event to outline his/her beliefs (but not his/her violent intentions). These statements include both letters sent to newspapers, self-printed/disseminated leaflets, and statements in virtual forums.

These findings suggest that friends, family, and coworkers can play important roles in efforts that seek to prevent or disrupt lone-actor terrorist plots. In many cases, those aware of the individual’s intent to engage in violence did not report this information to the relevant authorities. It is important therefore to provide information to the wider public on the behavioral indicators of radicalization to violence as well as appropriate outlets for this information to be reported and subsequently investigated. In any event, this finding may have significant implications for the development of operational investigations.

Indeed, most of the variables related to others having knowledge of the lone actor’s views and intent were far more common across lone actors than any sociodemographic characteristics. This suggests that lone-actor terrorists should largely be characterized by what they do rather than who they are.

Finding 3: A wide range of activities and experiences preceded lone actors’ plots or events.

Although the authors found it is more important to focus on what lone-actor terrorists do than who they are, it is still important to recognize that no single set of behaviors underpins lone-actor terrorism. Half of the sample changed address at least five years prior to their terrorist event planning or execution. Of the 40% who were unemployed, 27% had lost their jobs within six months, and a further 16% between seven and twelve months before the event. On a related note, 25% experienced financial problems. Thirty-three percent of the offenders were characterized as being under an elevated level of stress due to a number of reasons. Of this subsample, 74% experienced elevated stress within a year of the terrorist plot or event. Approximately one in five of those lone actors in gainful employment demonstrated worsening work performance in the buildup to their terrorist plot or event. Fifteen percent subjectively experienced being the target of an act of prejudice or unfairness, 19% subjectively experienced being disrespected by others, and 14% experienced being the victim of verbal or physical assault. A fifth of the sample converted to a religion before engaging or planning to engage in an event. Thirteen percent noticeably increased their physical activities and outdoor excursions.

Thus, behaviorally, the lone-actor terrorist sample was also diverse. The behaviors related to the individual’s radicalization and trajectory into terrorism were not overly similar from case to case. Similarly, the rhythm and tempo of each developmental trajectory also differed.

Finding 4: Many but not all lone-actor terrorists were socially isolated.

More than a quarter of the sample (27%) adopted their radical ideology when living away from home in another town, city, or country. Thirty-seven percent lived alone at the time of their event planning and/or execution, and 53% were characterized as socially isolated by sources within the coded open-source accounts.

Some lone-actor terrorists experienced problems with personal relationships. In these cases, social isolation tended not to be a long-standing occurrence but instead was derived from more recent interpersonal conflict. For example, 31% experienced problems in close personal relationships (e.g., family, romantic relationships). Of this subsample, 33% experienced these difficulties within the 6 months prior to planning or conducting their terrorist event. Eleven percent of the full sample experienced being ignored or treated poorly by someone important to them in the buildup to their terrorist plot or event. Additionally, 8% experienced someone important to them demonstrating that they did not care about the individual in the buildup to their offense.

A popular perception exists that lone-actor terrorists are isolated from the rest of society while their grievances grow and plots develop. This is perhaps best illustrated by the example of Ted Kaczynski, the so-called “Unabomber.” Collectively, however, lone-actor terrorists are more likely to be socially embedded within wider networks than be socially isolated. While those who are socially isolated are a minority, they do represent a specific threat to investigations that rely upon intercepting communications or receiving warnings from friends and family. Efforts aimed at combating socially isolated lone actors may additionally need to consider issues pertaining to the supply chain of weapons, bombing materials, and the operational manuals that are available online.

Finding 5: Lone-actor terrorists regularly engaged in a detectable and observable range of activities with a wider pressure group, social movement, or terrorist organization.

Approximately a third of the sample had recently joined a wider group, organization, or movement that engaged in contentious politics. Just less than a half (48%) interacted face-to-face with members of a wider network of political activists, and 35% did so virtually. In 68% of the cases, there is evidence to suggest that the individual read or consumed literature or propaganda associated with a wider movement. Fourteen percent previously engaged in fundraising or financial donations to a wider network of individuals associated with either licit pressure groups or illicit groups who espoused violent intentions. One in six (17%) sought legitimization from religious, political, social, or civic leaders prior to the event they planned.

There is evidence to suggest that in 17% of the cases there may have been wider command and control links specifically associated with the violent event that was planned or carried out. In approximately a third of the cases (35%), the lone actor had tried to recruit others or form a group prior to the event. In 24% of cases, other individuals were involved in procuring weaponry or technology that was used (or planned to be used) in the terrorist event but did not themselves plan to participate in the violent actions. In 13% of cases, other individuals helped the lone actor assemble an explosive device.

Much of the concern regarding lone-actor terrorism stems from the particular challenges of detecting and intercepting lone-actor terrorist events before they occur. Although they vary significantly in their effectiveness, there is a common perception that lone-actor plots are virtually undetectable. The traditional image of a lone-actor terrorist is that of an individual who creates his/her own ideology and plans and executes attacks with no help from others. Our findings suggest, however, that many lone-actor terrorists regularly interact with wider pressure groups and movements either face-to-face or virtually. This suggests that traditional counterterrorism measures (such as counterintelligence, HUMINT, interception of communications, surveillance of persons etc.) may have applicability to the early detection of certain lone-actor terrorists at specific moments in their pathway toward violence.

Finding 6: Lone-actor terrorist events were rarely sudden and impulsive.

Training for the plot typically occurred in a number of ways. Approximately a fifth of the sample (21%) received some form of hands-on training, while 46% learned through virtual sources. In half the cases, investigators found evidence of bomb-making manuals within the offender’s home or on his or her property. The fact that much strategic and tactical planning goes into lone-actor terrorist events is demonstrated by the finding that 29% of offenders engaged in dry runs of their intended activities.

Typically, lone-actor terrorist events emerge from a gradual chain of behaviors. This chain includes the steps of adopting an extremist ideology, thinking about engaging in violence, acquiring the necessary materials and/or training, and finally committing the offense. These behaviors may be observable prior to the commission of events. Although the development of a lone-actor terrorist event is rarely impulsive, at times there is very little time between the offender choosing to use violence and committing an attack.

Finding 7: Despite the diversity of lone-actor terrorists, there were distinguishable differences between subgroups.

While no uniform profile exists across our sample, there were significant differences when we compared subgroups. For example, compared to right-wing offenders and single-issue offenders, those inspired by al-Qaeda were younger and more likely to be students and to have sought legitimization from epistemic authority figures. They were also more likely to learn through virtual sources and display some form of command and control links. Right-wing offenders were more likely to be unemployed and less likely to have any university experience, make verbal statements to friends and family about their intent or beliefs, and engage in dry runs or obtain help in procuring weaponry. Single-issue offenders were more likely to be in a relationship, have criminal convictions, have a history of mental illness, provide specific pre-event warnings, and engage in dry runs. They were less likely to learn through virtual sources or have others aware of their planning.

This suggests the importance of not treating all lone-actor terrorists homogeneously and may have implications both for prevention and disruption as well as subsequent investigation.

Future Directions

While the data, analysis, and findings throughout this article are novel and important, it has only scratched the surface of what is a deeply complex and unfolding contemporary phenomenon. Together the results suggest the importance of focusing upon an analysis of behavior rather than attempting to identify and subsequently interpret what are realistically only semi-stable (at best) sociodemographic characteristics. What we lack, however, is an adequate control group to fully realize the significance of some of the descriptive findings. While the subgroup comparisons consistently found significant differences, it would be worthwhile to open the observations and data collection protocols to those individuals involved in fully or semi-autonomous groups. Through such an endeavor, a comparative approach would illustrate whether the descriptive findings related to antecedent behaviors and experiences are inherent to lone-actor terrorists or whether they are part of a wider trajectory in terrorism as a whole. An understanding of these dynamics would provide a wider evidence base to inform counterterrorism policies and practices. On a much more aspirational scale, there is also little evidence of the prevalence of these variables among the wider public and thus how much they truly distinguish lone-actor terrorists from law-abiding citizens.

Other methodologies will also provide other further insight. At the time of writing, there remain no publicly available interviews undertaken by researchers with lone-actor terrorists with the specific purpose of understanding how individuals decide to undertake violence as an individual, absent of formal terrorist group membership. Little is also known about the individual sociopsychological and practical constraints that need to be overcome to successfully execute a lone-actor terrorist attack. Finally, the finding that many of our sample had performed acts of criminality prior to their terrorist plotting suggests that it may be worthy to analyze these individuals from a criminal careers perspective. Such a perspective would provide insight into how individuals desist from one illegal activity and ultimately transition toward other illegal (but politically or socially driven) activities.

References

- Chermak SM, Freilich JD, Simone J. Surveying American state police agencies about lone wolves, far-right criminality, and far-right and Islamic Jihadist criminal collaboration. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2010;33:1019–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan J. Leaderless resistance. Terrorism Polit Violence. 1997;9(3):80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Spaaij R. The enigma of lone wolf terrorism: an assessment. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2010;33:854–70. [Google Scholar]

- Waits C, Shors D. Unabomber: the secret life of Ted Kaczynski. Helena, MT: Helena Independent Record; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Michel L, Herbeck D. American terrorist: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma city bombing. New York, NY: Harper; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Willman D. The mirage man: Bruce Ivins, the anthrax attacks, and the America’s rush to war. New York, NY: Bantam; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Pantucci R. 2011. A typology of lone wolves: preliminary analysis of lone Islamist terrorists. Report for the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, http://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/1302002992ICSRPaper_ATypologyofLoneWolves_Pantucci.pdf.

- Horgan J, Gill P. Who becomes a dissident? Patterns in the mobilisation and recruitment of violent dissident Republicans. In: Taylor M, Currie M, editors. Dissident Irish republicanism. London, U.K: Continuum Press; 2011. pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom M, Gill P, Horgan J. Tiocfaidh ar mna: women in the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Behav Sci Terrorism Polit Aggr. 2012;4(1):60–76. [Google Scholar]

- Reinares F. Who are the terrorists? Analyzing changes in sociological profile among members of ETA. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2004;27:465–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom M. Bombshell: women and terrorism. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Simcox R, Stuart H, Ahmed H. Islamist terrorism: the British connections. London, U.K: Center for Social Cohesion; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Florez-Morris M. Joining guerrilla groups in Colombia: individual motivations and processes for entering a violent organization. Stud Conflict Terrorism. 2007;30(7):615–34. [Google Scholar]

- Gill P, Horgan J. Who were the Volunteers? The shifting sociological and operational profile of 1240 Provisional Irish Republican Army members. Terrorism Polit Violence. 2013;25(3):435–56. [Google Scholar]

- Sageman M. Understanding terror networks. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fair C. Who are Pakistan’s militants and their families? Terrorism Polit Violence. 2008;20(1):49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Horgan J, Morrison JF. Here to stay? The rising threat of violent dissident Republicanism in Northern Ireland. Terrorism Polit Violence. 2008;23:642–69. [Google Scholar]

- Vossekuil B, Fein RA, Reddy M, Borum R, Modzeleski W. The final report and findings of the safe school initiative: implications for the prevention of school attacks in the United States. Washington, DC: United States Secret Service and United States Department of Education; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Merari A. A classification of terrorist groups. Terrorism. 1978;1(3–4):331–46. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz R. Conceptualizing political terrorism: a typology. J Int Aff. 1978;31(1):7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Asal V, Rethemeyer K. The nature of the beast: the organizational and network characteristics of organizational lethality. J Polit. 2008;70:437–49. [Google Scholar]