Significance

Translation of hepatitis C virus (HCV) RNA is facilitated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that binds small (40S) ribosomal subunits via ribosomal protein and 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) interactions. Using an rRNA expression system developed in this laboratory, we demonstrate that IRES activity requires a 3-nt Watson–Crick base-pairing interaction between the IRES and 18S rRNA of 40S ribosomal subunits. The specific intermolecular interaction appears to be unique to the HCV IRES and is a potential therapeutic target in Hepatitis C disease. In addition, by expressing compatible mutated HCV IRES-18S rRNA pairs, we were able to program translation of specific mRNAs by recombinant but not wild-type 40S subunits. This example suggests practical applications of rRNA engineering in mammalian cells.

Keywords: hepatitis C virus, 18S rRNA, IRES, base pairing, translation

Abstract

Degeneracy in eukaryotic translation initiation is evident in the initiation strategies of various viruses. Hepatitis C virus (HCV) provides an exceptional example—translation of the HCV RNA is facilitated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that can autonomously bind a 40S ribosomal subunit and accurately position it at the initiation codon. This binding involves both ribosomal protein and 18S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) interactions. In this study, we evaluate the functional significance of the rRNA interaction and show that HCV IRES activity requires a 3-nt Watson–Crick base-pairing interaction between the apical loop of subdomain IIId in the IRES and helix 26 in 18S rRNA. Mutations of these nucleotides in either RNA dramatically disrupted IRES activity. The activities of the mutated HCV IRESs could be restored by compensatory mutations in the 18S rRNA. The effects of the 18S rRNA mutations appeared to be specific inasmuch as ribosomes containing these mutations did not support translation mediated by the wild-type HCV IRES, but did not block translation mediated by the cap structure or other viral IRESs. The present study provides, to our knowledge, the first functional demonstration of mRNA–rRNA base pairing in mammalian cells. By contrast with other rRNA-binding sites in mRNAs that can enhance translation as independent elements, e.g., the Shine–Dalgarno sequence in prokaryotes, the rRNA-binding site in the HCV IRES functions as an essential component of a more complex interaction.

HCV is a single-stranded RNA virus that is a major cause of severe liver disease. The RNA genome contains a large ORF and expresses a single polypeptide that is processed into smaller proteins, which are necessary for replication and assembly of viral particles. The RNA genome is uncapped, and translation does not require the eukaryotic initiation factor 4F (eIF4F) complex (1), which mediates cap-dependent translation. Instead, translation is facilitated by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) located in the 5′ nontranslated region (2, 3). Inasmuch as the production of all HCV proteins requires the HCV IRES, the HCV IRES is a therapeutic target (4).

IRESs encompass a variety of initiation mechanisms and have been extensively studied in viruses, which often exploit the translation capabilities of the host for their own use (5–7). In many cases, the IRES mechanism complements the infection strategy of the virus. In the case of the HCV IRES and other IRESs of this type, the IRES can effectively recruit the host translation machinery by directly binding to 40S ribosomal subunits (1, 8–12). The HCV–ribosome interaction has been shown to require an interaction with ribosomal protein S25 (13) and can also involve the eIF3 complex, which increases the stability of the interaction (14). In the presence of ternary complex, which contains the initiator Met-tRNA, a preinitiation complex can assemble at the start site.

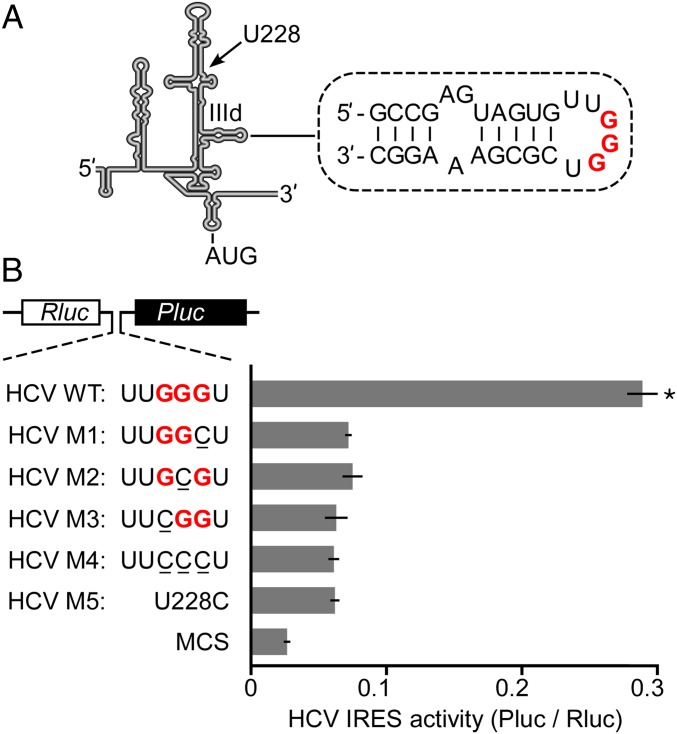

Various studies have investigated the binding of the HCV IRES to 40S subunits and identified interactions with several ribosomal proteins by cross-linking (1, 15–17). Interaction via 18S rRNA was first highlighted in a cryo-EM study of the IRES complexed with 80S ribosomes where the apical loop of subdomain IIId of the IRES (Fig. 1A) was found to make contact with the apical loop of helix 26 in 18S rRNA (18) (Fig. S1A).

Fig. 1.

Recombinant 18S rRNA supports HCV IRES-dependent translation. (A) Schematic representation of the secondary structure of the HCV IRES (modified from ref. 26 with permission from Oxford University Press). The location and sequence of domain IIId (nucleotides 266–268) is indicated; the position of U228 at the junction connecting subdomains a–c is shown by the arrow. The sequence of subdomain IIId is shown, and the three nucleotides that bind to 18S rRNA helix 26 are indicated in red bold type. (B) Reporter assays of N2a cells coexpressing recombinant mouse 18S rRNA (wild-type) and a dicistronic reporter construct. The reporter constructs contain the wild-type HCV IRES (HCV WT) or mutations in domain IIId of the IRES (HCV M1–M4), as indicated. The 5′-3′ convention for writing nucleotide sequences is used throughout the figures where sequences are not explicitly labeled. The negative control contains an MCS. A control mutation, U228C (HCV M5), is located at another site in the HCV IRES (see A). The results are reported as IRES activity by normalizing Pluc activity with Rluc activity. Error bars show SD from three independent experiments. An asterisk indicates significance between HCV WT and each of the other constructs (P value < 0.01 in two-sample t tests).

More recently, Hashem et al. (12) observed this interaction at higher resolution and suggested that it is probably mediated by base pairing between nucleotides 266GGG268 of subdomain IIId (HCV subtype 1b numbering) and 1118CCC1120 of helix 26 in 18S rRNA (mouse numbering). This IRES-rRNA interaction is supported by studies showing that mutations in the HCV IRES at nucleotides 266GGG268, which are predicted to disrupt base pairing to 18S rRNA, drastically reduced the binding affinity of the IRES to 40S subunits (8, 19). These mutations also disrupted IRES activity, both in vitro and in cells (19–23). In addition, when complexed with 40S subunits, the IIId loop of the HCV IRES was protected from cleavage by RNase T1 (8, 24) or from modification by kethoxal (25). Moreover, the HCV IRES protects the region 1115AUUCCC1120 of helix 26 in 18S rRNA from hydroxyl radical cleavage and 1118CCC1120 from dimethyl sulfate modification (26).

Although a strong indication for the intermolecular interaction between HCV IRES and 18S rRNA has been provided by various studies (see above), they are largely limited to cell-free experiments. Other studies that used equivalent or the same methodologies, however, failed to observe the interactions; e.g., see refs. 16, 27, and 28. This discrepancy may be due in part to different conditions or materials used in the experiments. Verifying a putative base-pairing interaction requires demonstrating that activity is disrupted by mutations that disrupt base-pairing potential, and is restored by compensatory mutations in the other RNA that restore pairing potential. It is only with evidence of this type that the functional relevance of a putative base-pairing interaction can be determined. However, until recently, it has not been possible to directly test the predicted pairing interaction as it has not been possible to analyze mutated 18S rRNAs in mammalian cells. Here, we test the predicted base-pairing interaction using a synthetic 18S rRNA expression system that we have developed in mouse cells (29). This system recapitulates the functionality of the native 18S rRNA, including the ability to support translation of exogenous genes.

Results and Discussion

Cells Expressing Synthetic 18S rRNA Support HCV IRES Activity.

We previously demonstrated that recombinant 18S rRNA expressed from a plasmid in mouse N2a cells was correctly processed and incorporated into fully functional ribosomal subunits capable of mediating global protein synthesis as well as translation driven by poliovirus and encephalomyocarditis virus IRESs (29). As an initial step toward a functional analysis of the hypothesized base-pairing interaction between HCV IRES and 18S rRNA, we examined whether our synthetic 18S rRNA expression system supports HCV IRES-dependent translation. Cells were transfected with a plasmid that expresses mouse 18S rRNA with a G963A mutation (mouse numbering) that confers resistance to pactamycin (Fig. S1A) (29). After 48 h, cells were subsequently transfected with a series of dicistronic reporter constructs, each encoding Renilla luciferase (Rluc) and Photinus luciferase (Pluc) from the first and second cistron, respectively (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B). These reporter constructs contained various intercistronic sequences, including a control multiple cloning site (MCS), which does not contain a known IRES, the wild-type HCV IRES, and mutated variants of this IRES. Pluc activity was normalized by the activity from the first cistron (Rluc) to report IRES-dependent translation activity as a ratio (Pluc/Rluc). Overnight incubations in the presence of pactamycin inhibited the activity of endogenous ribosomes, and the activity of recombinant pactamycin-sensitive ribosomes to less than ∼3% of the activity of ribosomes containing recombinant pactamycin-resistant 18S rRNAs (Fig. S1C). The activity of endogenous ribosomes was determined by comparing raw Renilla luciferase values from cells coexpressing dicistronic reporter constructs and pactamycin-sensitive or pactamycin-resistant recombinant 18S rRNAs, in the presence of pactamycin.

In cells expressing the wild-type recombinant 18S rRNA, the activity of the wild-type HCV IRES is more than tenfold higher than that of the negative control MCS sequence (Fig. 1B). G-to-C point mutations in the HCV IRES at 266GGG268 of the IIId apical loop, which are hypothesized to disrupt base pairing with helix 26 in 18S rRNA, reduced expression by 3.9- to 4.6-fold (Fig. 1B). The effects of these mutations are consistent with those observed in rabbit reticulocyte lysate (19, 20) and are most likely due to a severe reduction in the ability of the IRES to bind to 40S ribosomal subunits (8). Notably, in the present study, the effects of these mutations were similar to that obtained for a control mutant, U228C at junction IIIabc (Fig. 1). This mutation has been reported to decrease IRES-dependent translation to the same degree as mutations at 266GGG268 (20), but without disrupting the formation of a 48S preinitiation complex (30). In our study, translation from defective HCV IRES mutants remained higher than the MCS control. We expect that these residual activities are most likely explained by cryptic promoter activity in the HCV IRES sequence (31), and/or by other interactions between the IRES and 40S subunits that are capable of supporting low levels of expression. To assess the contribution of cryptic promoter activity in our system, we tested a promoterless construct (Fig. S2). For this construct, Rluc activity was reduced to ∼0.05%; however, Pluc was still expressed at ∼3.8% of the wild-type IRES, indicating that a low level of Pluc activity was at least partially due to cryptic promoter activity in our system.

Mutations in 18S rRNA Specifically Affect HCV IRES Activity.

Recently, Malygin et al. reported that 1115AUUCCC1120 in 18S rRNA was highly accessible to hydroxyl radicals, particularly 1117UCCC1120 (26). This region of 18S rRNA was not accessible when bound to an in vitro transcribed HCV IRES RNA. These nucleotides are located in the apical loop of helix 26. Nucleotides 266GGG268 of the HCV IRES can potentially base pair to this site in the 18S rRNA via two possible interactions:

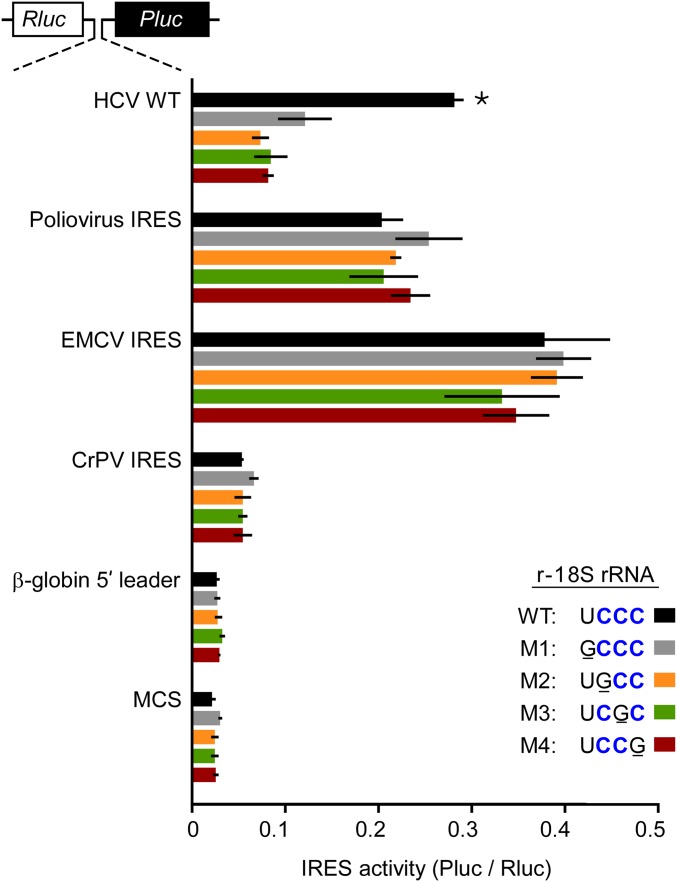

To assess the importance of these four nucleotides in 18S rRNA to HCV IRES activity, we individually mutated each nucleotide between 1117UCCC1120 of 18S rRNA to G. We observed that each point mutation reduced IRES activity by 2.4- to 3.9-fold (Fig. 2). In contrast, the same 18S rRNA mutations did not significantly affect the activities of IRESs from poliovirus, encephalomyocarditis virus, or cricket paralysis virus. Background expression from control constructs containing the MCS or the β-globin 5′ leader, which is cap-dependent and does not contain an IRES, were unaffected by the 18S rRNA mutations. Moreover, 5′-cap-dependent translation appeared to be unaffected by these mutations as raw Rluc activities, which were derived from the first cistron of the dicistronic transcripts, were not altered significantly (P values ≥ 0.45; Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

Mutation of HCV-binding site in 18S rRNA disrupts HCV IRES activity. N2a cells were cotransfected with an 18S rRNA construct and a dicistronic reporter construct as indicated. The 18S rRNA constructs varied in the 4-nt apical loop sequence of helix 26. Constructs included wild-type (r-18S WT) and mutated (r-18S M1–M4) sequences. The dicistronic constructs varied in the intercistronic sequence; these sequences included the wild-type HCV IRES (HCV WT), as well as IRESs from poliovirus, encephalomyocarditis virus, and cricket paralysis virus. In addition, MCS and β-globin 5′ leader sequences were used as negative controls that do not contain known IRES elements. The data are represented as IRES activities (Pluc/Rluc ratios). Error bars show SD (n = 3). An asterisk indicates a P value <0.01 in two-sample t tests for HCV WT with r-18S WT against the HCV WT expressed with the other r-18S constructs. One-way ANOVA was used to analyze results obtained from the same reporter construct.

It should be noted that the r-18S M1 mutation in 18S rRNA (1117GCCC1120; the mutated nucleotide is indicated in bold and underlined) reduced IRES activity to a level similar to that of the other point mutations. However, it is possible that this mutation may have stabilized rather than disrupted an interaction with the HCV IRES by enabling an extended base-pairing interaction with 266GGGU269, and preventing subsequent steps in the initiation process. Alternatively, the r-18S M1 mutation may have disrupted the appropriate positioning of the neighboring sequence for base pairing with the HCV IRES element. In any case, it is evident that nucleotide 1117U of 18S rRNA plays a specific role in HCV IRES-dependent translation.

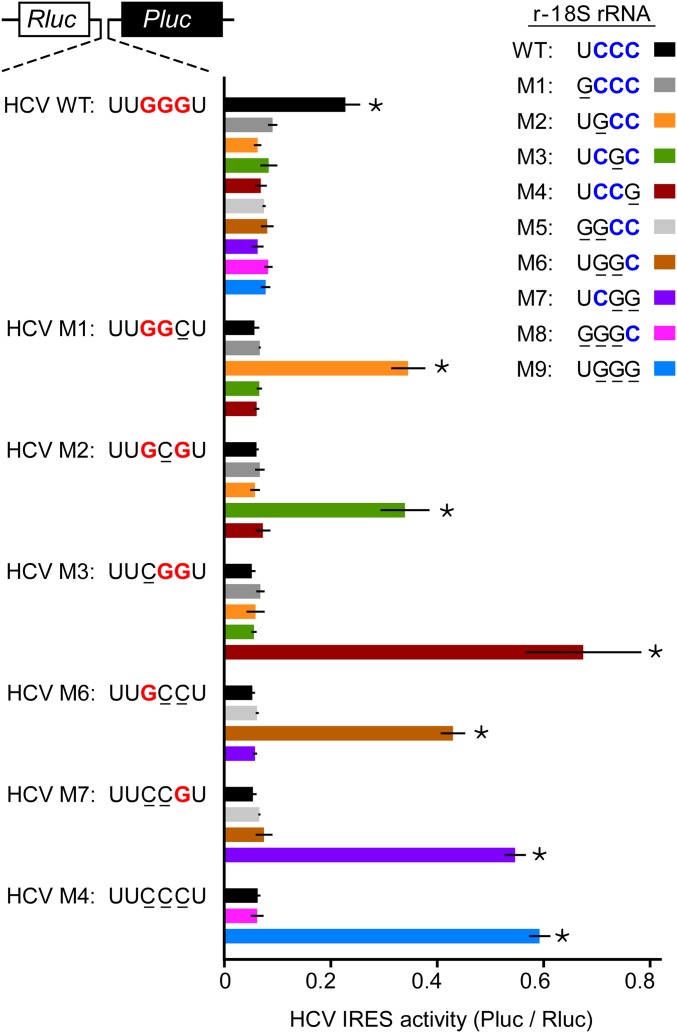

Activity of the HCV IRES Requires Base Pairing to 18S rRNA.

Mutations in the HCV IRES (Fig. 1) and 18S rRNA (Fig. 2) support the notion that the GGG sequence in domain IIId of the HCV IRES base pairs to four nucleotides in the loop of helix 26 of 18S rRNA. To directly test this postulated base-pairing interaction, we determined whether mutations in the HCV IRES that disrupt both complementarity and IRES activity could be rescued by compensatory mutations in the 18S rRNA. The results showed that mononucleotide, dinucleotide, and trinucleotide mutations in the HCV IRES disrupted its activity (Fig. 3). Compensatory mutations in the apical loop of helix 26 in 18S rRNA were able to rescue IRES activity. For example, the HCV IRES with mutation M1 (264UUGGCU269) remained highly active only in cells transfected with plasmid p18S-M2, which contains a mutation in the 18S rRNA that restores complementarity to the mutated IRES: 1117UGCC1120. Importantly, the activity of the wild-type HCV IRES was severely impaired in cells expressing ribosomes containing any of the mutated 18S rRNAs. Similarly, for the HCV IRES mutations, translation efficiencies of the noncomplementary pairs were significantly decreased by 3.8- to 11.2-fold in comparison with the complementary pairs.

Fig. 3.

Various complementary matches between 18S rRNA and HCV RNA support IRES activity. N2a cells were cotransfected with an 18S rRNA construct and a dicistronic reporter construct as indicated. The sequences of the 18S rRNAs at nucleotides 1117–1120 in the WT and mutated (r-18S M1−M9) constructs are shown. The dicistronic constructs contain HCV WT or a mutation in the apical loop of domain IIId as shown (HCV M1–M4; M6, M7). The data are represented as IRES activity (Pluc/Rluc ratios). Error bars show SD (n ≥ 3). An asterisk indicates a P value <0.01 in two-sample t tests that were performed with the matched HCV–r-18S pairs against the nonmatched pairs within the same reporter construct.

Northern blot analysis across all samples showed that the recombinant 18S rRNAs were expressed at similar levels and could not account for the different translation efficiencies observed with the various IRES−18S rRNA pairs (Fig. S4A). In addition, analyses of recombinant 18S rRNAs expressed from both p18S−1117GGGC1120 (M8) and p18S−1117UGGG1120 (M9), which are incapable and capable of rescuing activity of HCV IIId M4 (266CCC268), respectively, exhibited similar distribution profiles of polysomal fractions (Fig. S4B). These distributions indicate that ribosomes containing the mutated rRNAs were functional. Indeed, Rluc activities translated from the first cistron of the dicistronic reporter constructs did not differ significantly among cells expressing the 18S rRNA mutants (Fig. S4C). These results argue against possible experimental artifacts arising from differences in either expression levels or activities of particular 18S rRNA variants.

Even with the possibility of an extended base-pairing interaction mentioned above as a potential limitation associated with the r-18S rRNA M1 mutation (1117GCCC1120), it seems unlikely that G1117 of 18S rRNA base pairs to C268 of the HCV IRES, as none of the 18S rRNAs that contain the U1117G mutation (r-18S M1; r-18S M5, and r-18S M8) were able to functionally restore any of the HCV IIId mutations (Fig. 3). One possibility is that U1117 may be important for correctly presenting the neighboring sequence for base pairing with the IRES. Consistent with this idea, a U1117C mutation, which may also be able to base pair with 268G of the wild-type IRES, resulted in reduced activity (Fig. S5). In contrast, the positional requirements for base pairing in the apical loop of subdomain IIId of the HCV IRES appear to be more flexible. It has been previously reported that a mutation in the HCV IRES (U265G/G268U), which converted the loop sequence of IIId from 264UUGGGU269 to 264UGGGUU269, retained ∼40% of the wild-type IRES activity in a cell-based assay (21). In another study, G-to-C mutations in this same region were found to induce a conformational change in the IRES (20). The fact that our studies show that these same mutations can be functionally rescued by compensatory mutations in 18S rRNA further suggests plasticity in the IRES.

Individual C-to-U point mutations in the 18S rRNA (nt 1,118–1,120) theoretically retain the potential to base pair with the HCV IRES 266GGG268. However, when we tested 18S rRNAs containing these mutations, we observed a severe reduction of HCV IRES activity (Fig. S5). This reduction in activity was equivalent to the levels seen with the C-to-G mutations (Figs. 2 and 3: r-18S M2–M9). These results may suggest that the HCV IRES requires a certain minimal threshold of base-pairing free energy for a functional interaction and/or that three consecutive G/C bases in helix 26 are specifically required for the 18S rRNA to base pair with the HCV IRES. It may be significant that some studies have reported that the HCV IRES can function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (32, 33). The yeast 18S rRNA contains a UUU sequence in the apical loop of helix 26, which may suggest that subdomain IIId of the IRES can base pair to 18S rRNA via G−U pairing. A plausible explanation for the observed differences between the results in mammalian cells and yeast may be temperature. Yeast are cultured at a lower temperature, which may increase the stability of the G−U base pairs.

Finally, to further address potential issues associated with IRES analyses using DNA reporter plasmids, such as cryptic promoter (31) and/or splicing activities, cells were transfected with in vitro capped reporter RNA constructs. RNA transfections were performed using the wild-type and M9 recombinant 18S rRNAs. The results of RNA transfection experiments mirrored those of the reporter plasmid transfections (Fig. S6). The results showed that the HCV IRES is active with the wild-type 18S rRNA but is inactive when the binding site in 18S rRNA is mutated from CCC to GGG. Activity of the mutated HCV IRES (M4), which has its binding site mutated from GGG to CCC, is inactive with the wild-type 18S rRNA. However, this mutated IRES is highly active with the M9 mutated 18S rRNA, which restores the complementary match. These results further confirm that base pairing of the HCV IRES to 18S rRNA is essential for HCV IRES activity. However, we found that the differences in IRES activities between complementary and noncomplementary pairs were even more evident in the RNA transfection experiments (11.8- to 120.3-fold difference) than in the DNA transfections (3.8- to 11.2-fold; Fig. 3). This result appears to be due to the higher level of background expression in the DNA transfection experiments.

For both DNA and RNA transfections, IRES-dependent translation efficiencies from the noncognate matched pairs were higher than from the wild-type HCV IRES−18S rRNA pair (Fig. 3 and Fig. S6). These results may suggest that the lower efficiency of the wild-type HCV IRES may be constrained by the 18S rRNA sequence.

The results of this study indicate that a 3-nt Watson–Crick base-pairing interaction between the HCV IRES and 18S rRNA is required for IRES-dependent translation initiation. This rather short, but crucial, contact is likely to be important for stabilizing the IRES−40S interaction. We have previously discussed mRNA–rRNA base pairing as a universal mechanism that can facilitate or selectively regulate translation, which is not restricted to bacteria (34–36). Using a yeast genetic system, we and others have previously demonstrated that this mechanism can facilitate translation initiation, reinitiation, and shunting (37–39). As with the HCV IRES, all of these mechanisms involve interactions with helix 26 in the 18S rRNA. Indeed, for calicivirus, reinitiation was shown to involve the same apical loop as the HCV IRES (39). The present study suggests that the apical loops of HCV IRES subdomain IIId and helix 26 in the 18S rRNA are potential therapeutic targets. Targeting the apical loop of helix 26 may also affect the translation of cellular mRNAs that interact with this region. However, to date, it is not known if any cellular mRNAs interact with this segment of 18S rRNA during translation initiation or elongation. This presumed population of mRNAs can be identified and characterized using the mutated recombinant 18S rRNAs developed in this study. To this end, it will be important to determine the scope of functional interactions mediated by the apical loop of helix 26 to assess whether potential treatments, e.g., using oligonucleotide masking approaches, will have the specificity required for treating hepatitis C.

Materials and Methods

DNA Constructs.

Constructs expressing mouse 18S rRNA (p18S series in this study) were based on p18S.1 (29). These constructs have a G-to-A point mutation at nt 963 (mouse numbering) that confers pactamycin resistance, and an insertion of a neutral hybridization tag for Northern blot analysis at the terminal loop of helix 44 (Fig. S1A). A dicistronic reporter construct encodes humanized Renilla luciferase (Rluc; Promega) and Photinus luciferase (Pluc; modified firefly luciferase, luc2, Promega) genes. All reporter plasmids have a common backbone sequence from pGL4.13 (Promega). The reporter constructs that contain the HCV IRES (Fig. S1B) or its mutational variants were generated by PCR. Intercistronic sequence cassettes that contain other viral IRESs and control sequences were cloned from reporter plasmids previously described in ref. 40. Transcription is driven by the CMV enhancer/promoter (PCR-cloned from pCI-neo; Promega), which is absent in the promoterless constructs.

RNA Reporter Constructs.

For RNA transfections, in vitro transcripts were generated from plasmids containing a T7 promoter in the place of the CMV enhancer/promoter of the corresponding plasmids. A 70-nt stretch of poly(A) was introduced 167 nucleotides downstream of the Pluc termination codon, which is the same position as that for mRNAs expressed in cells from the CMV constructs. The poly(A) extends immediately upstream of a BamHI restriction site, which was used to linearize the plasmids before in vitro transcription reactions. Capped in vitro transcripts were generated by using mMessage mMachine (Ambion), and subsequently quantified by UV absorption at 260 nm. The mRNA quality was monitored by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

Analysis of Reporter Gene Activity.

Mouse Neuro 2a (N2a) cells were seeded in 24-well plates at 2.5 × 104 cells per well and transfected the next day using 0.4 µg p18S plasmid with 1.2 µL of PolyJet transfection reagent (SignaGen) per well. At 48 h posttransfection, media were exchanged with those containing pactamycin (500 ng/mL; Sigma), and incubated for ∼30 min at 37 °C before a subsequent transfection. Cells were transfected with reporter constructs (0.2 µg reporter plasmid with 0.6 µL PolyJet or 1 µg in vitro transcribed capped RNA with 3 µL PolyJet), and cultured overnight. Finally, cells were lysed with 250 µL per well of Passive Lysis Buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured with Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay reagent (Promega) using an EG&G Berthold luminometer. Translation efficiency was expressed as a ratio, Pluc/Rluc. For statistical analysis, two-sample t test (one-sided) or one-way ANOVA was used to determine P values; P values < 0.01 are indicated in the figures where applicable. Averages and SDs were calculated within each set of experiments from at least three biological replicates with independent transfections.

Analysis of rRNA Expression and Synthetic Ribosomes.

Preparation of total RNA from transfected cells was performed essentially as described previously (41). Expression levels of the recombinant 18S rRNAs were determined by Northern analysis as described previously (29) with the exception of using a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide probe (5′-GATATTCGGCAAGCAGGC-3′) that detected the hybridization tag sequence in helix 44 (Fig. S1A) or a probe (5′-CCAGGGCCGTGGGCCGAC-3′) that detected endogenous 18S rRNAs. Hybridization signals were visualized using PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Polysome analysis of cells expressing p18S as well as the subsequent primer extension analysis of the fractionated samples were performed as described previously (29), except that cells were seeded at 1.75 × 106 per 10-cm dish the day before and 6 µg of an appropriate p18S plasmid was used for transfection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Stephen A. Chappell and John Dresios for critical discussions and reading of the manuscript. The authors also thank Luke Burman for technical assistance. Funding was provided by Promosome SFP 1539.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1413472111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pestova TV, Shatsky IN, Fletcher SP, Jackson RJ, Hellen CUT. A prokaryotic-like mode of cytoplasmic eukaryotic ribosome binding to the initiation codon during internal translation initiation of hepatitis C and classical swine fever virus RNAs. Genes Dev. 1998;12(1):67–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsukiyama-Kohara K, Iizuka N, Kohara M, Nomoto A. Internal ribosome entry site within hepatitis C virus RNA. J Virol. 1992;66(3):1476–1483. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1476-1483.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang C, Sarnow P, Siddiqui A. Translation of human hepatitis C virus RNA in cultured cells is mediated by an internal ribosome-binding mechanism. J Virol. 1993;67(6):3338–3344. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.6.3338-3344.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piñeiro D, Martinez-Salas E. RNA structural elements of hepatitis C virus controlling viral RNA translation and the implications for viral pathogenesis. Viruses. 2012;4(10):2233–2250. doi: 10.3390/v4102233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doudna JA, Sarnow P. Translation initiation by viral internal ribosome entry sites. In: Matthews MB, Sonenberg N, Hershey JW, editors. Translation Control in Biology and Medicine. 2nd Ed. John Inglis; New York: 2009. pp. 129–153. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kieft JS. Viral IRES RNA structures and ribosome interactions. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33(6):274–283. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohr I, Sonenberg N. Host translation at the nexus of infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(4):470–483. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kieft JS, Zhou K, Jubin R, Doudna JA. Mechanism of ribosome recruitment by hepatitis C IRES RNA. RNA. 2001;7(2):194–206. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201001790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lytle JR, Wu L, Robertson HD. Domains on the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site for 40s subunit binding. RNA. 2002;8(8):1045–1055. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202029965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spahn CM, et al. Hepatitis C virus IRES RNA-induced changes in the conformation of the 40s ribosomal subunit. Science. 2001;291(5510):1959–1962. doi: 10.1126/science.1058409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filbin ME, Vollmar BS, Shi D, Gonen T, Kieft JS. HCV IRES manipulates the ribosome to promote the switch from translation initiation to elongation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(2):150–158. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hashem Y, et al. Hepatitis-C-virus-like internal ribosome entry sites displace eIF3 to gain access to the 40S subunit. Nature. 2013;503(7477):539–543. doi: 10.1038/nature12658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landry DM, Hertz MI, Thompson SR. RPS25 is essential for translation initiation by the Dicistroviridae and hepatitis C viral IRESs. Genes Dev. 2009;23(23):2753–2764. doi: 10.1101/gad.1832209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fraser CS, Doudna JA. Structural and mechanistic insights into hepatitis C viral translation initiation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(1):29–38. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fukushi S, et al. Ribosomal protein S5 interacts with the internal ribosomal entry site of hepatitis C virus. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(24):20824–20826. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otto GA, Lukavsky PJ, Lancaster AM, Sarnow P, Puglisi JD. Ribosomal proteins mediate the hepatitis C virus IRES-HeLa 40S interaction. RNA. 2002;8(7):913–923. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202022057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Babaylova E, et al. Positioning of subdomain IIId and apical loop of domain II of the hepatitis C IRES on the human 40S ribosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(4):1141–1151. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boehringer D, Thermann R, Ostareck-Lederer A, Lewis JD, Stark H. Structure of the hepatitis C virus IRES bound to the human 80S ribosome: Remodeling of the HCV IRES. Structure. 2005;13(11):1695–1706. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolupaeva VG, Pestova TV, Hellen CU. Ribosomal binding to the internal ribosomal entry site of classical swine fever virus. RNA. 2000;6(12):1791–1807. doi: 10.1017/s1355838200000662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kieft JS, et al. The hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site adopts an ion-dependent tertiary fold. J Mol Biol. 1999;292(3):513–529. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jubin R, et al. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site (IRES) stem loop IIId contains a phylogenetically conserved GGG triplet essential for translation and IRES folding. J Virol. 2000;74(22):10430–10437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10430-10437.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otto GA, Puglisi JD. The pathway of HCV IRES-mediated translation initiation. Cell. 2004;119(3):369–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barría MI, et al. Analysis of natural variants of the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site reveals that primary sequence plays a key role in cap-independent translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(3):957–971. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolupaeva VG, Pestova TV, Hellen CU. An enzymatic footprinting analysis of the interaction of 40S ribosomal subunits with the internal ribosomal entry site of hepatitis C virus. J Virol. 2000;74(14):6242–6250. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6242-6250.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lukavsky PJ, Otto GA, Lancaster AM, Sarnow P, Puglisi JD. Structures of two RNA domains essential for hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site function. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7(12):1105–1110. doi: 10.1038/81951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malygin AA, Kossinova OA, Shatsky IN, Karpova GG. HCV IRES interacts with the 18S rRNA to activate the 40S ribosome for subsequent steps of translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(18):8706–8714. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shenvi CL, Dong KC, Friedman EM, Hanson JA, Cate JH. Accessibility of 18S rRNA in human 40S subunits and 80S ribosomes at physiological magnesium ion concentrations—Implications for the study of ribosome dynamics. RNA. 2005;11(12):1898–1908. doi: 10.1261/rna.2192805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto H, et al. Structure of the mammalian 80S initiation complex with initiation factor 5B on HCV-IRES RNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2014;21(8):721–727. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burman LG, Mauro VP. Analysis of rRNA processing and translation in mammalian cells using a synthetic 18S rRNA expression system. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(16):8085–8098. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ji H, Fraser CS, Yu Y, Leary J, Doudna JA. Coordinated assembly of human translation initiation complexes by the hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(49):16990–16995. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407402101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dumas E, et al. A promoter activity is present in the DNA sequence corresponding to the hepatitis C virus 5′ UTR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(4):1275–1281. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosenfeld AB, Racaniello VR. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site-dependent translation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is independent of polypyrimidine tract-binding protein, poly(rC)-binding protein 2, and La protein. J Virol. 2005;79(16):10126–10137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.16.10126-10137.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Masek T, et al. Hepatitis C virus internal ribosome entry site initiates protein synthesis at the authentic initiation codon in yeast. J Gen Virol. 2007;88(Pt 7):1992–2002. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.82782-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mauro VP, Edelman GM. rRNA-like sequences occur in diverse primary transcripts: Implications for the control of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(2):422–427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauro VP, Edelman GM. The ribosome filter hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(19):12031–12036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192442499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mauro VP, Edelman GM. The ribosome filter redux. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(18):2246–2251. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.18.4739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dresios J, Chappell SA, Zhou W, Mauro VP. An mRNA-rRNA base-pairing mechanism for translation initiation in eukaryotes. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13(1):30–34. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chappell SA, Dresios J, Edelman GM, Mauro VP. Ribosomal shunting mediated by a translational enhancer element that base pairs to 18S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(25):9488–9493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603597103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luttermann C, Meyers G. The importance of inter- and intramolecular base pairing for translation reinitiation on a eukaryotic bicistronic mRNA. Genes Dev. 2009;23(3):331–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.507609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chappell SA, Edelman GM, Mauro VP. A 9-nt segment of a cellular mRNA can function as an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) and when present in linked multiple copies greatly enhances IRES activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(4):1536–1541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuda D, Mauro VP. Determinants of initiation codon selection during translation in mammalian cells. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(11):e15057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.