Abstract

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is overexpressed in human prostate cancer and uPAR has been found to be associated with metastatic disease and poor prognosis. AE105 is a small linear peptide with high binding affinity to uPAR. We synthesized an N-terminal NOTA-conjugated version (NOTA-AE105) for development of the first 18F-labeled uPAR positron-emission-tomography PET ligand using the Al18F radiolabeling method. In this study, the potential of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 to specifically target uPAR-positive prostate tumors was investigated.

Methods

NOTA-conjugated AE105 was synthesized and radiolabeled with 18F-AlF according to a recently published optimized protocol. The labeled product was purified by reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography RP-HPLC. The tumor targeting properties were evaluated in mice with subcutaneously inoculated PC-3 xenografts using small animal PET and ex vivo biodistribution studies. uPAR-binding specificity was studied by coinjection of an excess of a uPAR antagonist peptide AE105 analogue (AE152).

Results

NOTA-AE105 was labeled with 18F-AlF in high radiochemical purity (> 92%) and yield (92.7%) and resulted in a specific activity of greater than 20 GBq/μmol. A high and specific tumor uptake was found. At 1 h post injection, the uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 in PC-3 tumors was 4.22 ± 0.13%ID/g. uPAR-binding specificity was demonstrated by a reduced uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 after coinjection of a blocking dose of uPAR antagonist at all three time points investigated. Good tumor-to-background ratio was observed with small animal PET and confirmed in the biodistribution analysis. Ex vivo uPAR expression analysis on extracted tumors confirmed human uPAR expression that correlated close with tumor uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105.

Conclusion

The first 18F-labeled uPAR PET ligand, 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105, has successfully been prepared and effectively visualized noninvasively uPAR positive prostate cancer. The favorable in vivo kinetics and easy production method facilitate its future clinical translation for identification of prostate cancer patients with an invasive phenotype and poor prognosis.

Keywords: uPAR, PET 18F, Prostate cancer

1. Introduction

Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) is overexpressed in a variety of human cancers [1], including prostate cancer (PCa), where uPAR expression in tumor biopsies and shed forms of uPAR in plasma have been found to be associated with advance disease and poor prognosis [2–8]. Moreover, in patients with localized PCa, high preoperative plasma uPAR levels have been shown to correlate with early progression [9]. Consistent with uPARs important role in cancer pathogenesis, through extracellular matrix degradation facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis, uPAR is considered an attractive target for both therapy [10,11] and imaging [12] and the ability to non-invasively quantify uPAR density in vivo is therefore crucial.

We have previously described the development, radiolabeling and in vivo evaluation of a small peptide radiolabeled with 64Cu [13] and 68Ga [14] for positron-emission-tomography PET imaging of uPAR in various human xenograft cancer models. We demonstrated the ability of these tracers to specifically differentiate between tumors with high and low uPAR expression and furthermore established a clear correlation between tumor uptake of the uPAR PET probe and the expression of uPAR15. However, 18F (t1/2 = 109.7 min; β+, 99%) is considered the ideal short-lived PET isotope for labeling of small molecules and peptides due to the high positron abundance, optimal half-life, wide availability, and short positron range.

Recently, an elegant one step radiolabeling approach was developed for radiofluorination of both small peptides and proteins based on complex binding of (Al18F)2+ using 1,4,7-triazacyclononane (NOTA) chelator [15–18]. In this method, the traditional critical azeotropic drying step for 18F-fluoride is not necessary, and the labeling can be performed in water. A number of recently published studies have illustrated the potential of this new 18F-labeling method, where successful labeling of ligands for PET imaging of angiogenesis [19,20], Bombesin [21], EGFR [22] and hypoxia [23] have been demonstrated.

The aims of the present study were therefore to synthesize a NOTA-conjugated peptide, to use the Al18F labeling method for development of the first 18F-labeled PET ligand for uPAR PET imaging, and to perform a biological evaluation of the resulting PET probe in human PCa xenograft tumors. To achieve this, we synthesized our previously published high-affinity uPAR binding peptide denoted AE105 and conjugated with NOTA in the N-terminal. 18F-labeling was done according to a recently optimized protocol26. The final product (18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105) was finally evaluated in vivo using both small animal PET imaging in human PCa (PC-3) bearing animals and after collection of organs for biodistribution study.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemical reagents

All chemicals obtained commercially were of analytical grade and used without further purification. No-carrier-added 18F-fluoride was obtained from an in-house PETtrace cyclotron (GE Healthcare). Reverse-phase extraction C18 Sep-Pak cartridges were obtained from Waters (Milford, MA, USA) and were pretreated with ethanol and water before use. The syringe filter and polyethersulfone membranes (pore size 0.22 μm, diameter 13 mm) were obtained from Nalge Nunc International (Rochester, NY, USA). The reverse phase high performance liquid chromatography RP-HPLC using a Vydac protein and peptide column (218TP510; 5 μm, 250 × 10 mm) was performed as previously described [19].

Small animal PET scans were performed on a microPET R4 rodent model scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc., Knoxville, TN, USA). The scanner has a computer-controlled bed and 10.8-cm transaxial and 8-cm axial fields of view (FOVs). It has no septa and operates exclusively in the three-dimensional (3-D) list mode. Animals were placed near the center of the FOV of the scanner.

2.2. Peptide synthesis, conjugation and radiolabeling

NOTA-conjugated AE105 (NOTA-Asp-Cha-Phe-(D)Ser-(D)Arg-Tyr-Leu-Trp-Ser-COOH) was purchased from ABX GmbH. The purity was characterized using HPLC analysis and the mass was confirmed using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) (Se Suppl. Fig. 1A). The radiolabeling of NOTA-AE105 with 18F-AlF is shown in Fig. 1 and was done according to a recently published protocol with minor modifications [24].

Fig. 1.

(A) In vitro competitive inhibition of the uPA:uPAR binding for AE105, AE152, NOTA-AE105 and 19 F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 using surface Plasmon resonance. (B) Radiolabeling method for 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105.

In brief, a QMA Sep-Pak Light cartridge (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was fixed with approximately 3 GBq of 18F-fluoride and then washed with 2.5 mL of metal free water. Na18F was then eluted from the cartridge with 1 mL saline, from which 100 μL of fraction was taken. Then amounts of 50 μL 0.1 M Na-Acetate buffer (pH = 4), 3 μL 0.1 M AlCl3 and 100 μL of Na18F in 0.9% saline (300 MBq) were first reacted in a 1 mL centrifuge tube (sealed) at 100 °C for 15 min. The reaction mixture was cooled. Ethanol (50μL) and 30 nmol NOTA-AE105 in 3 μL DMSO were added and the reaction mixture were heated to 95 °C for 5 min. The crude mixture was purified with a semi-preparative HPLC. The fractions containing 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 were collected and combined in a sterile vial. The product was diluted in phosphatebuffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4) so any organic solvents were below 5% (v/v) and used for in vivo studies.

2.3. In vitro affinity

To test whether chelation with NOTA or labeling with Al-F had any influence on binding affinity of AE105 the IC50 values of the synthetic peptides for inhibition of the uPA · uPAR interaction were measured by surface plasmon resonance using a Biacore using a Biacore T100 operated at 20 °C and a flow rate of 50 μl/min with running buffer (i.e., 10 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM EDTA, and 0.1 % (v/v) surfactant P-20 at pH 7.4). In brief, purified recombinant human prouPA was immobilized on a CM5 sensor chip by amine coupling. A low concentration of purified uPAR (10 nM) was preincubated with serial threefold dilutions of the peptides and their chelated and labelled versions covering 0.1 nM to 300 μM.

2.4. Cell line and animal model

Human prostate cancer cell line PC-3 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and culture media DMEM was obtained from Invitrogen Co. (Carlsbad, CA, USA). The cell line was cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 1% (v/v) penicillin/ Streptomycin at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Animal procedures were performed according to a protocol approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Xenografts of human PC-3 prostate cancer cells were established by injection of 200 μL cells (1 × 108 cells/mL) suspended in 100 μL Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA), subcutaneously in the right flank of male nude mice obtained from Charles River Laboratory (Wilmington, MA. USA), Tumors were allowed to grow to a size of 0.6–1 cm (3–4 weeks).

2.5. MicroPET imaging

Three min static PET scans were acquired 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 h post injection (p.i.) of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 via tail-vein injection of 2–3 MBq (n = 4). Similar, the blocking study was performed by injection of the PET probe together with 100 μg of AE152 (uPAR antagonist) through the tail vein (n = 4) and PET scans were performed at the same time points. During each three minutes PET scan, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (5% induction and 2% maintenance in 100% O2). Images were reconstructed using a twodimensional ordered subsets expectation maximization (OSEM-2D) algorithm. No background correction was performed.

All results were analyzed using Inveon software (Siemens Medical Solutions) and PET data was expressed as percentage of the injected radioactive dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g) based on manual regionof-interests (ROIs) drawing on PET images and the use of a calibration constant. An assumption of a tissue density of 1 g/ml was used. No attenuation correction was performed.

2.6. Biodistribution studies

After the last PET scan, all PC-3 bearing mice were euthanized. Blood, tumor and major organs were collected (wet-weight) and the radioactivity was measured using a γ-counter from Perkin Elmer, MA, USA (N = 4 mice/group). The radioactivity uptake in the tumor and normal tissues was expressed as a % ID/g.

2.7. uPAR ELISA

uPAR ELISA on dissected PC-3 tumors was done as described previously in detail [13]. All results were performed as duplicate measurements.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean) and means were compared using Student t-test. Correlation statistics was done using linear regression analysis. A P-value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Inhibitory effect of the peptides on the uPAR:uPA interaction

The inhibitory effects (IC50) on the uPAR:uPA interaction of AE105, NOTA-AE105 and 19 F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 were in this study found to be 14.1, 24.5 and 21.0 nM respectively (Fig. 1A). These results are in line with our previously published data [13,14], and confirm the ability to make modifications in the N-terminal of AE105 with only limited reduction in the ability to antagonize the interaction between uPAR and uPa [12,25,26].

3.2. Radiochemistry

The 18F-labeling of NOTA-AE105 was synthesized based on a recently published procedure with some modifications (Fig. 1B). During our labeling optimization, we found that 33% ethanol (v/v) was optimal using 30 nmol NOTA-AE105. We first formed the 18F-AlF complex in buffer at 100 °C for 15 min. Secondly the NOTA-conjugated peptide was added and incubated together with ethanol at 95 °C for 5 min. By adding ethanol we were able to increase the overall yield to above 92.7%, with a radiochemical purity above 92% in the final product (Fig. 2C), whereas the yield without ethanol was only 30.4%, with otherwise same conditions. No further increase in the overall yield was observed using longer incubation time and/or different ethanol concentrations or using less than 30 nmol conjugated peptide. Two isomers were observed for 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105.

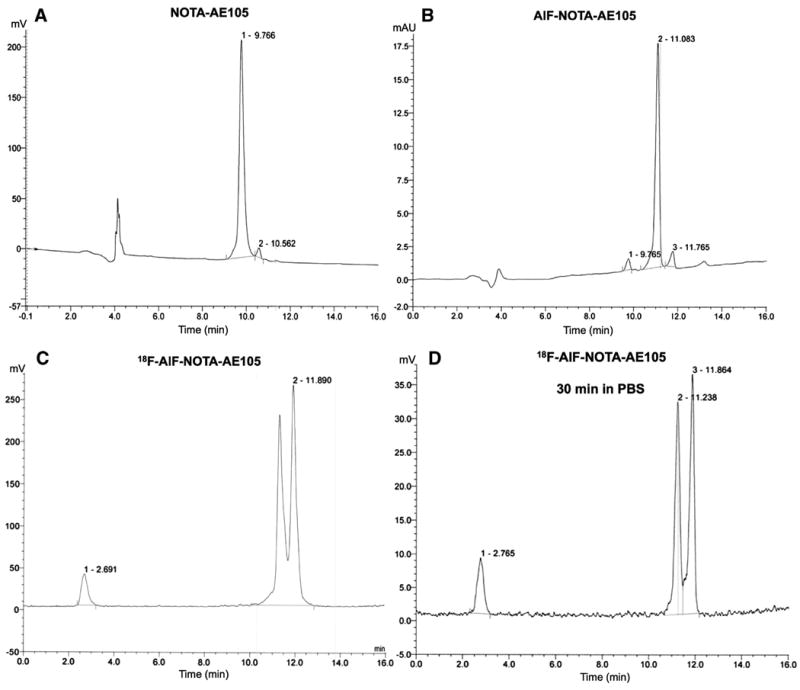

Fig. 2.

Representative HPLC UV chromatograms ofNOTA-AE105 (A), cold standard AlF-NOTA-AE105 (B) and radio chromatograms for the final product 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 (C) and after 30 min in PBS (D).

In order to ensure the formation of the right product, a cold standard of the final product was synthesized (AlF-NOTA-AE105). The HPLC analysis of the precursor (NOTA-AE105, Fig. 2A) confirmed the purity of the NOTA-conjugated precursor (>97%) and MALDITOF-MS confirmed the mass (1511.7 Da) (See suppl. figure 1). The cold standard (AlF-NOTA-AE105, Fig. 2B), with the right mass confirmed by MALDI-TOF-MS (1573.6 Da) (See suppl. figure 1B), corresponded well in regards to retention time with the ‘hot’ product (Fig. 2C), thus confirming the formation of 18F-AlF-NOTAAE105 (Fig. 2C). For the cold standard, only one product was formed, whereas two radioactive peaks were observed for the radioactive product. This is properly caused by difference in the reaction conditions, were the cold standard is formed using equal amount of peptide and AlF whereas during the formation of the radioactive product the amount of peptide is much larger than the amount of 18F-AlF. No degradation of the final product was found after 30 min in PBS (Fig. 2D). The radioactive peaks were collected and diluted in PBS and used for in vivo studies. The specific activity in the final product was above 20 GBq/μmol.

3.3. In vivo PET imaging

18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 was injected i.v. in four mice bearing PC-3 tumors and PET scans were performed 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 h p.i. Tumor lesions were easily identified from the reconstructed PET images (Fig. 3A), and ROI analysis revealed a high tumor uptake, with 5.90 ± 0.35 %ID/g after 0.5 h, declining to 4.22 ± 0.13 %ID/g and 2.54 ± 0.24 %ID/g after 1.0 and 2.0 h, respectively (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

(A) Representative PET images after 0.5 h, 1.0 h and 2.0 h p.i. of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 (top) and 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 with a blocking dose of AE152 (100 μg). White arrows indicate tumor. (B) Quantitative ROI analysis with tumor uptake values (%ID/g). A significant higher tumor uptake was found in normal group than those of the blocking group at all three time points. Results are shown as %ID/g ± SEM (n = 4 mice/group). ** P < 0.01, *** P > 0.001 vs. blocking group at same time point.

In order to ensure that the found tumor uptake indeed reflected specific uPAR mediated uptake, four new PC-3 tumor bearing mice were then injected with a mixed solution containing 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 and 100 μg of the high-affinity uPAR binding peptide denoted AE152, in order to see if the tumor uptake could be inhibited. A significant lower amount of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 tumor uptake was found at all three time points investigate (Fig. 3B) and tumor lesions were not as easily identified in the PET images (Fig. 3A). At 1.0 h p.i. a tumor uptake of 1.86 ± 0.14 %ID/g was found in the blocking group compared with 4.22 ± 0.13 %ID/g found in the group of mice receiving only 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 (P b 0.001, 2.3 fold reduction).

3.4. Biodistribution

After the last PET scan, each group of mice were euthanized and selected organs and tissues were collected to investigate the biodistribution profile at 2.5 h p.i. (Fig. 4). A significant higher tumor uptake in the group of mice receiving 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 was found compared with blocking group (1.02 ± 0.37 %ID/g vs. 0.30 ± 0.06 %ID/g, P < 0.05), thus confirming the specificity of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 for human uPAR found in the PET study. Highest activity was found in the kidneys for both groups of mice, confirming the kidneys to be the primarily route of excretion. Beside kidneys, the bone, well known to accumulate fluoride, also had a moderate uptake of 3.54 ± 0.32 %ID/g and 2.34 ± 0.33 %ID/g for normal and blocking group, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Biodistribution results for 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 (normal) and 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 + blocking dose of AE152 (blocking) in nude mice bearing PC-3 tumors at 2.5 h p.i. Results are shown as %ID/g ± SEM (n = 4mice/group). * P < 0.05 vs. blocking group.

3.5. uPAR expression

Both the PC-3 cells used for tumor inoculation and all PC-3 tumors at the end of the study (n = 8) were finally analyzed for confirming expression of human uPAR (Fig. 5). An expression in the cells of 6.53 ± 1.6 ng/mg protein was found (Fig. 5A), whereas the expression level in the dissected tumors was 302 ± 129 pg/mg tumor tissue (Fig. 5B). A significant correlation between tumor uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 and uPAR expression was found (P < 0.05, r2 = 0.86 (Fig. 5C)).

Fig. 5.

uPAR expgression level found using ELISA in PC-3 cells (A) and in dissected PC-3 tumors (B). (C) A significant correlation between uPAR expression and tumor uptake was found in the four mice injected with 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 (P < 0.05, r2 = 0.86, n = 4 tumors).

4. Discussion

Our study as the first, describes synthesis and applicability of an 18F-labeled ligand for uPAR PET. We characterized the ligand in a human prostate cancer xenograft mouse model. Based on the obtained results, similar tumor uptake, specificity and tumor-tobackground contrast were found compared to our previously published studies using 64Cu- and 68Ga-based ligands for PET [13,14]. Based on the superior physical characteristics of 18F and the high tumor-to-background contrast found already after 1 h p.i., our new 18F-based ligand must be considered the so far most promising uPAR PET candidate for translation into clinical use in order to non-invasively characterize invasive potential of e.g. prostate cancer.

18F-labeling of peptides using the AlF-approach has previously been described to be performed at 100 °C for 15 min, at pH = 4 [15–18]. We had to modify this protocol, since degradation of the NOTA-conjugated peptide was observed using these conditions. We therefore first produced the 18F-AlF complex using the above mentioned conditions and next added our NOTA-conjugated peptide and lowered the temperature to 95 °C, and within 5 min obtained a labeling yield of 92.7% and with no degradation of the peptide. Two isomers of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 were produced. Same observations have been reported by others for 18F-AlF-NOTA-Octreotide [16] and all NOTA-conjugated IMP peptide analogues described [17]. The ratios of the two peaks were nearly constant for each labeling and both radioactive peaks were collected and used for further in vivo studies. This approach was recently also described by others [24]. The same group has also recently developed a new binding ligand NODA-MPAEM [27], suitable for AlF-based labeling of proteins at room temperature in a two-step procedure, thus eliminating the limitations currently present due to the high temperatures needed for efficient labeling.

Besides optimizing the temperature and time, we found that the addition of ethanol, to a final concentration of 33% (v/v), resulted in a significant higher labeling yield, compared with radiolabeling without ethanol (30.4% vs. 92.7%), using the same amount of NOTA-conjugated peptide. Same observations have recently been described by others [24]. Here the effect of lowering the ionic strength was investigated using both acetonitrile, ethanol, dimethylforamide and tetrahydrofuran at different concentrations. A labeling yield of 97% was reported using ethanol at a concentration of 80% (v/v). However, they used between 76–383 nmol NOTA-conjugated peptide, whereas we in this study only used 30 nmol. The amount needed for optimal labeling yield therefore seems to be dependent on the peptide and on the amount of peptide used for labeling.

The tumor uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 was similar compared with our previously published 64Cu-based ligands [13]. The tumor uptake 1 h p.i. was 4.79 ± 0.7%ID/g, 3.48 ± 0.8%ID/g and 4.75 ± 0.9%ID/g for 64Cu-DOTA-AE105, 64Cu-CB-TE2A-AE105, 64Cu-CB-TE2A-PA-AE105 compared to 4.22 ± 0.1%ID/g for 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105. However, all 64Cu-based ligands were investigated using the human glioblastoma cell line U87MG, whereas in this study, the prostate cancer cell line PC-3 was used. Considering that our data show that the level of uPAR in the two tumor types is not similar, with PC-3 having around 300 pg uPAR/mg tumor tissue (Fig. 5B) and U87MG having approximately 1,700 pg/mg tumor tissue (unpublished), the tumor uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 seems to be relatively higher per pg uPAR, However, a direct comparison between the two independent studies is difficult, considering the different cancer cell line used. We have previously shown a significant correlation between uPAR expression and tumor uptake across three tumor types [13], which is confirmed in the present study using PC-3 xenografts (Fig. 5C), further validating the ability of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 to quantify uPAR expression using PET imaging. The uPAR specific binding of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 in the present study was confirmed by a 2.3-fold reduction in tumor uptake of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 1 h p.i. when co-administration of a uPAR antagonist (AE152) was performed for blocking study.

The biodistribution study of 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 confirmed the kidneys to be the primary route of excretion and the organ with highest level of activity (Fig. 4). Same excretion profiles have been found for 68Ga-DOTA/NODAGA-AE105 [14], 177Lu-DOTA-AE105 [28]. Besides the kidneys and tumor, the bone also had a relatively high accumulation of activity. Bone uptake following injection of 18F-based ligands is a well-described phenomenon and used clinically in NaF bone scans [29]. We found a bone uptake of 3.54 %ID/g 2.5 h p.i., which is similar to the bone uptake following 18F-FDG injection in mice, where 2.49 %ID/g have been reported 1.5 h p.i. [15], suggesting this level of defluorination of the probe is acceptable for clinical imaging. The reason for the reduced uptake in most organs in the blocking experiment, we believe is cause by an altered kinetic of our PET ligand due to injection of excess amount of cold peptide (AE152). However, our results surprisingly indicate a partly receptor-mediated uptake in non-tumor organs also exist. Similar phenomena have been reported in numerous studies for integrin-binding RGD-based peptides in human xenograft mouse models [19]. Future studies will have to show whether this phenomenon also plays a role in other species and in a clinical setting.

The development of the first 18F-based ligand for uPAR PET provides of number of advantages compared to our previously published 64Cu-based uPAR PET ligands. Considering the optimal tumor-to-background contrast as early as 1 h p.i. as found in this study and in previously studies using 64Cu, the relatively shorter halflife of 18F (T1/2 = 1.83 h) compared with 64Cu (T1/2 = 12.7 h) seems to be optimal, considering the much lower radiation burden to future patients using 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105. Moreover, the production of 18F is well established in a number of institutions worldwide, whereas the production of 64Cu still is limited to relatively few places.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we have synthesized and characterized the first 18F-labeled ligand for uPAR PET imaging using a human PCa xenograft mouse model. The new PET ligand is based on 18F-AlF and a NOTA-conjugated uPAR binding peptide. High and specific tumor uptake was found. We conclude that 18F-AlF-NOTA-AE105 seems to be a highly promising ligand for uPAR PET imaging of the invasive phenotype with high potential of clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by The Danish National Research Foundation (Centre for Proteases and Cancer), Danish Medical Research Council, the Strategi Research Council, the Danish National Advanced Technology Foundation, the Novo Nordisk Foundation, the Lundbeck Foundation, the A.P. Moeller Foundation, the Arvid Nilsson Foundation, the Svend Andersen Foundation, DOD-PCRP-NIA PC094646, and In vivo Cellular Molecular Imaging Center (ICMIC) grant P50 CA114747.

Footnotes

Disclosure: No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Supplementary materials related to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2013.03.001.

Contributor Information

Zhen Cheng, Email: zcheng@stanford.edu.

Andreas Kjaer, Email: akjaer@sund.ku.dk.

References

- 1.Rasch MG, Lund IK, Almasi CE, Hoyer-Hansen G. Intact and cleaved uPAR forms: diagnostic and prognostic value in cancer. Front Biosci. 2008;13:6752–62. doi: 10.2741/3186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyake H, Hara I, Yamanaka K, Gohji K, Arakawa S, Kamidono S. Elevation of serum levels of urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor is associated with disease progression and prognosis in patients with prostate cancer. Prostate. 1999 May;39(2):123–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990501)39:2<123::aid-pros7>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyake H, Hara I, Yamanaka K, Arakawa S, Kamidono S. Elevation of urokinasetype plasminogen activator and its receptor densities as new predictors of disease progression and prognosis in men with prostate cancer. Int J Oncol. 1999 Mar;14(3):535–41. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.3.535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piironen T, Haese A, Huland H, Steuber T, Christensen IJ, Brunner N, et al. Enhanced discrimination of benign from malignant prostatic disease by selective measurements of cleaved forms of urokinase receptor in serum. Clin Chem. 2006 May;52(5):838–44. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.064253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steuber T, Vickers A, Haese A, Kattan MW, Eastham JA, Scardino PT, et al. Free PSA isoforms and intact and cleaved forms of urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in serum improve selection of patients for prostate cancer biopsy. Int J Cancer. 2007 Apr;120(7):1499–504. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta A, Lotan Y, Ashfaq R, Roehrborn CG, Raj GV, Aragaki CC, et al. Predictive value of the differential expression of the urokinase plasminogen activation axis in radical prostatectomy patients. Eur Urol. 2009 May;55(5):1124–33. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2008.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nogueira L, Corradi R, Eastham JA. Other biomarkers for detecting prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2010 Jan;105(2):166–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.09088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shariat SF, Semjonow A, Lilja H, Savage C, Vickers AJ, Bjartell A. Tumor markers in prostate cancer I: blood-based markers. Acta Oncol. 2011 Jun;50:61–75. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2010.542174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shariat SF, Roehrborn CG, McConnell JD, Park S, Alam N, Wheeler TM, et al. Association of the circulating levels of the urokinase system of plasminogen activation with the presence of prostate cancer and invasion, progression, and metastasis. J Clin Oncol. 2007 Feb;25(4):349–55. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.6853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabbani SA, Ateeq B, Arakelian A, Valentino ML, Shaw DE, Dauffenbach LM, et al. An anti-urokinase plasminogen activator receptor antibody (ATN-658) blocks prostate cancer invasion, migration, growth, and experimental skeletal metastasis in vitro and in vivo. Neoplasia. 2010 Oct;12(10):778–88. doi: 10.1593/neo.10296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulukuri SM, Gondi CS, Lakka SS, Jutla A, Estes N, Gujrati M, et al. RNA interferencedirected knockdown of urokinase plasminogen activator and urokinase plasmin-ogen activator receptor inhibits prostate cancer cell invasion, survival, and tumorigenicity in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005 Oct;280(43):36529–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503111200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Kriegbaum MC, Persson M, Haldager L, Alpízar-Alpízar W, Jacobsen B, Gårdsvoll H, et al. Rational targeting of the urokinase receptor (uPAR): development of antagonists and non-invasive imaging probes. Curr Drug Targets. 2011 Nov;12(12):1711–28. doi: 10.2174/138945011797635812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Persson M, Madsen J, Ostergaard S, Jensen MM, Jorgensen JT, Juhl K, et al. Quantitative PET of human urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor with 64Cu-DOTA-AE105: implications for visualizing cancer invasion. J Nucl Med. 2012 Jan;53(1):138–45. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.083386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Persson M, Madsen J, Ostergaard S, Ploug M, Kjær A. (68)Ga-labeling and in vivo evaluation of a uPAR binding DOTA- and NODAGA-conjugated peptide for PET imaging of invasive cancers. Nucl Med Biol. 2012 May;39(4):560–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, D'Souza CA, Rossi EA, Laverman P, et al. A novel method of 18 F radiolabeling for PET. J Nucl Med. 2009 Jun;50(6):991–8. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.060418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laverman P, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Eek A, Joosten L, Oyen WJ, et al. A novel facile method of labeling octreotide with (18)F-fluorine. J Nucl Med. 2010 Mar;51(3):454–61. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.066902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride WJ, D'Souza CA, Sharkey RM, Karacay H, Rossi EA, Chang CH, et al. Improved 18 F labeling of peptides with a fluoride-aluminum-chelate complex. Bioconjug Chem. 2010 Jul;21(7):1331–40. doi: 10.1021/bc100137x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D'Souza CA, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Todaro LJ, Goldenberg DM. High-yielding aqueous 18 F-labeling of peptides via Al18F chelation. Bioconjug Chem. 2011 Sep;22(9):1793–803. doi: 10.1021/bc200175c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu S, Liu H, Jiang H, Xu Y, Zhang H, Cheng Z. One-step radiosynthesis of (1)(8)F-AlF-NOTA-RGD(2) for tumor angiogenesis PET imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2011 Sep;38(9):1732–41. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-1847-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gao H, Lang L, Guo N, Cao F, Quan Q, Hu S, et al. PET imaging of angiogenesis after myocardial infarction/reperfusion using a one-step labeled integrin-targeted tracer 18 F-AlF-NOTA-PRGD2. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2012 Apr;39(4):683–92. doi: 10.1007/s00259-011-2052-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dijkgraaf I, Franssen GM, McBride WJ, D'Souza CA, Laverman P, Smith CJ, et al. PET of tumors expressing gastrin-releasing peptide receptor with an 18 F-labeled bombesin analog. J Nucl Med. 2012 Jun;53(6):947–52. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heskamp S, Laverman P, Rosik D, Boschetti F, van der Graaf WT, Oyen WJ, et al. Imaging of human epidermal growth factor receptor type 2 expression with 18 F-labeled affibody molecule ZHER2:2395 in a mouse model for ovarian cancer. J Nucl Med. 2012 Jan;53(1):146–53. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.093047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoigebazar L, Jeong JM, Lee JY, Shetty D, Yang BY, Lee YS, et al. Syntheses of 2-nitroimidazole derivatives conjugated with 1,4,7-triazacyclononane-N, N′-diacetic acid labeled with F-18 using an aluminum complex method for hypoxia imaging. J Med Chem. 2012 Apr;55(7):3155–62. doi: 10.1021/jm201611a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laverman P, D'Souza CA, Eek A, McBride WJ, Sharkey RM, Oyen WJ, et al. Optimized labeling of NOTA-conjugated octreotide with F-18. Tumour Biol. 2012 Apr;33(2):427–34. doi: 10.1007/s13277-011-0250-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ploug M, Ostergaard S, Gårdsvoll H, Kovalski K, Holst-Hansen C, Holm A, et al. Peptide-derived antagonists of the urokinase receptor. affinity maturation by combinatorial chemistry, identification of functional epitopes, and inhibitory effect on cancer cell intravasation. Biochemistry. 2001 Oct;40(40):12157–68. doi: 10.1021/bi010662g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ploug M. Structure-function relationships in the interaction between the urokinase-type plasminogen activator and its receptor. Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9(19):1499–528. doi: 10.2174/1381612033454630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McBride WJ, D'Souza CA, Sharkey RM, Goldenberg DM. The radiolabeling of proteins by the [18 F]AlF method. Appl Radiat Isot. 2012 Jan;70(1):200–4. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson M, Rasmussen P, Madsen J, Ploug M, Kjaer A. New peptide receptor radionuclide therapy of invasive cancer cells: in vivo studies using (177)Lu-DOTAAE105 targeting uPAR in human colorectal cancer xenografts. Nucl Med Biol. 2012 Oct;39(7):962–9. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurdziel KA, Shih JH, Apolo AB, Lindenberg L, Mena E, McKinney YY, et al. The kinetics and reproducibility of 18 F-sodium fluoride for oncology using current PET camera technology. J Nucl Med. 2012 Aug;53(8):1175–84. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.100883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.