Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to discover and characterize components of engagement in creative activity as occupational therapy for elderly people dealing with life-threatening illness, from the perspective of both clients and therapists. Despite a long tradition of use in clinical interventions, key questions remain little addressed concerning how and why people seek these activities and the kinds of benefits that may result.

Method

Qualitative interviews were conducted with 8 clients and 7 therapists participating in creative workshops using crafts at a nursing home in Sweden. Analysis of the interviews was conducted using a constant comparative method.

Findings

Engaging in creative activity served as a medium that enabled creation of connections to wider culture and daily life that counters consequences of terminal illness, such as isolation. Creating connections to life was depicted as the core category, carried out in reference to three subcategories: (1) a generous receptive environment identified as the foundation for engaging in creative activity; (2) unfolding creations—an evolving process; (3) reaching beyond for possible meaning horizons.

Conclusion

The findings suggest that the domain of creative activity can enable the creation of connections to daily life and enlarge the experience of self as an active person, in the face of uncertain life-threatening illness. Ultimately, the features that participants specify can be used to refine and substantiate the use of creative activities in intervention and general healthcare.

Keywords: Creative activity, elderly, life-threatening illness, occupational therapists

Introduction

The use of creative occupations has a long tradition in occupational therapy intervention (1,2). The roots of this tradition have been traced to the arts and crafts movement (3,4). In line with this tradition the term creative activity is used in this paper for craft-oriented activities. In current clinical practice the use of such activities, especially for elderly people, can be seen as workshop activities in nursing homes and day care, for example with ceramics, silk paint, and gardening (5). Despite or perhaps due to its deep historical roots the “value” of creative occupations is largely accepted as “good” to do, but has received little critical examination. Indeed, there is limited empirical research reporting evidence validating the efficacy or mechanisms of these interventions. Unanswered key questions remain including why and more specifically how such occupations may benefit persons dealing with serious illness. Lacking a clearer understanding of the fundamental features by which such tangible and concrete creative activities may be helpful, we are limited in our ability to critically evaluate and justify their use or to extend their benefits more widely.

The potential value of and interest in using creative activities for psychosocial interventions is increasing for several reasons, including growing numbers of elderly people and improved survival rates for a range of serious illness conditions, such as cancer (6). Thus, rising numbers of elderly are facing a period of living with significantly difficult illness coupled with better treatments for previously fatal events (e.g. stroke). When people encounter life-threatening illness, they experience a disruption in their habituated sense of daily life (7). The disruption is often experienced as an inner disarray and outwardly as problems in carrying out basic daily activities, due partly to the physical features of the disease itself but also to social isolation (6,8). To regain a sense of meaningful order the person must rework prior understandings of self and develop new strategies to approach daily life (5,8). Consequently, one important challenge in care of the elderly becomes the client’s ability to handle the consequences and salient everyday life concerns of incurable illness and to develop methods for therapeutic intervention (5). Creative occupations have been identified as a central feature in the framework of human experience, especially with regard to making meaning and individual development (9–12). Creative occupation is an integral part of basic processes of adaptation and health throughout the life span and is linked directly to well-being (13–15). The psychologist May (16) extends this line of reasoning by proposing that creativity operates to change the individual’s understanding of everyday life and enable handling of difficult experiences by carrying symbolic meaning, permitting transcendence over material conditions. He defines creative activity as involving inventiveness and the making of something new by giving life to an idea.

Further, contemporary philosophical discourses argue that humans understand themselves and their participation in a social and material world through aesthetic and narrative forms (17–20). That is, making meaning of human action is linked to creative processes.

Another interesting perspective on creative occupations highlights one element with direct implications for therapeutic use. Simonton (21) and Luborsky (22) suggest that creativity is evoked and more fully engaged when acting to confront and grapple with limits and challenges (23). Creativity emerges as individuals grapple with the challenge to rearrange practices, ideas, and values that redefines connections among materials and people. This line of reasoning is analogous to that of several narrative theorists, who argue that the creation of stories is a communicative act within the boundaries and possibilities of the surrounding intrinsic and extrinsic world (3,18,29).

Luborsky (22,24) argues that intrinsic limit in materials, objects, or bodily and social activity focuses on and brings out creativity; it does not emerge in a vacuum, divorced from the settings and demands of life. In other words, it is through work with materials such as wood or clay that the individual can experience limitations and in turn creativity is stimulated. Arguably, creativity is called for in confronting both normative life-cycle developmental transitions, and non-normative life events involving health and disease experiences.

The body of empirical research on the use of creativity and more specific creative activities in elderly care is relatively limited (22,26). However, some important contributions are relevant in this context. In a study by Luborsky (22) the role of creativity was examined among the elderly in terms of how they construct meaning for their whole lifetime. The findings from analyses of in-depth study of non-directed life-story narratives showed that creation of life narratives could enable personal meanings and well-being, depending on attitude and approach to understanding the life stories. The findings from this study call for creative specificity, that is, the need to attend to the individual’s particular self-defined sense of challenges and the available social and personal resources to meet these. However, it should be noted that the population in this study was not suffering from life-threatening illness.

Other studies examining creative activity in relation to the elderly and disease take a perspective either on a diagnosis or a specific activity, such as going to a museum and engaging in needlecraft or pottery (6,26–28). Results in common of these studies are that engagement in cultural and creative occupations can play an important role by providing patients with relief from problems, increasing self-esteem, and improving health.

Although the research described above identifies a positive influence on health from participation in creative occupations, it also reveals crucial gaps in the research base of our knowledge. These gaps concern knowledge regarding the underlying mechanisms and components that make creative activity work as an intervention. Further, we know little about how and why engagement in creative activity contributes, in this case for the elderly, when confronted with incurable illness. Findings reported in this paper will explore concrete creative activity in the form of craft-oriented activities such as pottery, silk-painting and gardening, rather than creativity in a more decontextualized or general sense. In particular, no studies have explored how elderly people with life-threatening illness describe their own engagement in specific creative activity in the context of occupational therapy intervention. Further, the use of creative activity in therapy can be viewed as a co-construction, which often involves at least two parties, the therapist and the client. Existing research does not address creative activity from such a perspective. Thus, there is a need to explore components of creative activities for elderly persons facing the personal implications of life-threatening illness, from both the client’s and therapist’s perspective.

The aim of this study was to discover and characterize components of engagement in creative activity as occupational therapy for elderly people dealing with life-threatening illness, from the perspective of both clients and therapists.

Material and methods

Setting

The study was carried out at a hospital and nursing home specializing in rehabilitation, palliative, and geriatric care. It adheres to an explicit philosophy to support the use of cultural and creative activities. The hospital and nursing home houses a maximum of 160 residents and provides day-care services to a varying number of outpatients.

The occupational therapy department conducted the creative workshops in three rooms on the ground floor. One room was large and bright with several tables to work at. In this room was a sofa corner, including a piano, for coffee and talk. A table was placed to be seen on entry to the room decorated with a creation intended as inspiration for the clients. Two other rooms were designed for crafts, one for pottery and one for woodwork. In each room creations, such as pottery, made by clients was exhibited. The surrounding garden was used as facility for planting seeds and other gardening activity. During the period of this project approximately 18 clients were registered for workshop activities.

Participants

A purposive sample (n = 15) of 8 clients and 7 therapists was recruited over a period of 6 months. Inclusion criteria for clients included attending the nursing home either as registered “patients” or daycare clients, being older than 60 years of age, and able to respond adequately to interview questions. All the 8 elderly clients who engaged in creative activities during that period and met the inclusion criteria were asked to participate by a therapist working at the nursing home, and all agreed.

Inclusion criteria for therapists included working with elderly clients and using creative activities during intervention. All 8 therapists working at the nursing home were asked to participate by the first author and 7 agreed. One cancelled several times and finally did not participate. All participants were involved in the same creative activities on different occasions. The term “participants” is used in this context to refer to both clients and therapists.

Approval for the study was obtained from the responsible ethical committee.

Interventions

The creative activities that participants engaged in included woodwork, pottery, silk painting, soap making, knitting and gardening. The workshops were offered in groups and on an individual basis. Two men engaged in creative activity individually (alone with a therapist), one man engaged both individually and through in-group activity and one man was in a group. Three women engaged in group-based creative activity and one did woodcarving individually.

The creative workshops were offered one to three times a week depending on need. Usually groups of 6–8 clients participated. The facilities are open for activity all week.

A typical day began when the clients arrive about 9.30 am. They started out with coffee and talk for about 30 minutes. Clients selected an activity of their choice and engaged in that for roughly 1–2 hours. For example when doing pottery, where clients and a therapist gathered around a common table, clients engaged in their own creations or watched and talked with others.

Data collection

Interviews were carried out using semi-structured qualitative interviews (29). A few main questions were developed to provide a shared initial structure for the interviews. To gain a fuller understanding of the participants, further questions were based on thoughts and issues they brought up. The two first authors conducted the interviews in collaboration, one primarily interviewing and the other listening actively and adding clarifying questions. The interview guide was piloted before collection of data. Interview questions addressed: how the individual experiences engagement in current creative activities in occupational therapy and within his/her own life; and the meaning attached to these experiences. Questions for the therapists concerned their experience of using creative activity with the elderly. Each therapist was asked to narrate an event when a client’s use of creative activity played a significant role.

Interviews with the clients took place in their residence (own room) at the nursing home or in the facilities of the occupational therapy department, such as the kitchen area. All therapists were interviewed in the occupational therapy facilities. Each interview lasted 30–45 minutes. All interviews were audio tape-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

The interviews were analysed using a comparative method (30). Initially, material from the clients and from the therapists was analysed separately. Then the material taken together across all clients and therapists was analysed. Analysis was conducted in a series of steps. First, each individual interview was read to gain familiarity with the person and central points were summarized in writing. Then, codes were assigned based on a line-by-line reading to identify main topics, initially using the interviewee’s own words and then moving to codes named by the researcher. By identifying and constantly comparing the relationships and patterns of differences and similarities between the different codes those with similar features were united into categories. For example the participants talked about memories of earlier experiences and plans for their creations, and what we termed “connections to life before and life to come” were recognized.

Initially a core category and six sub-categories were identified. The core category was a topic that occurred consistently in the analysis. Further review led us to reorganize the six sub-categories in different constellations; two were collapsed into one and two were discarded as not being consistently important for the aim of the study. Finally three sub-categories related to the core category were conceptualized with their properties characterizing the main components of experiences with creative activity in intervention. These will be explained in the results section. Developing abstract conceptualization of categories was conducted as a back-and-forth process to constantly fit analytic concepts to the data.

To establish trustworthiness and limit biases, analysis of the interviews was first conducted independently by the first author. This was then examined by the second author, a senior researcher, and by peer review by fellow doctorate students. Reviews included reflections on the order and structure of categories, for example questions concerning the identified process, which enabled further clarification of the results. The findings described in the following are those agreed on by the researchers and reviewers.

Results

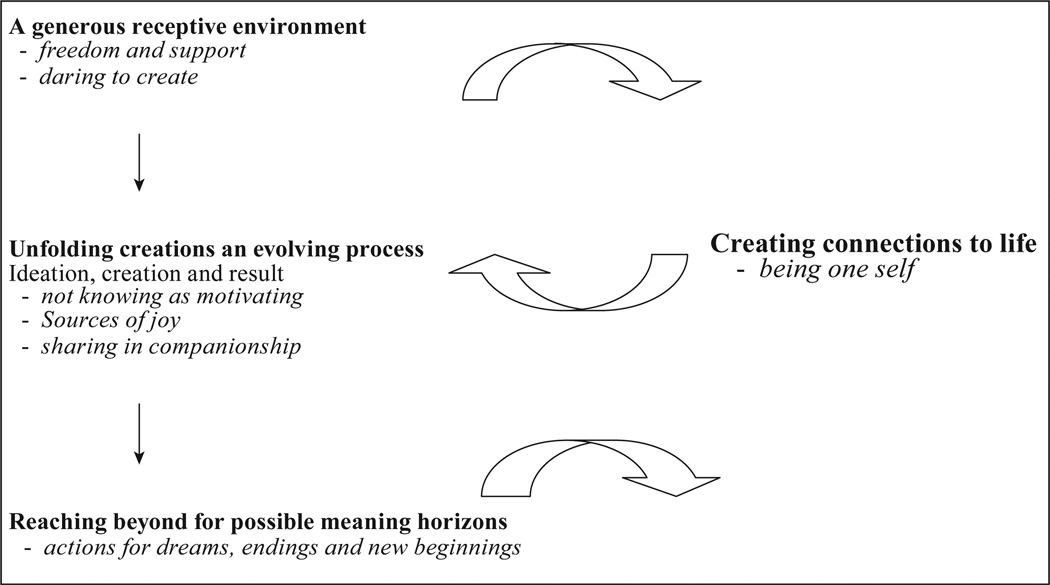

Analysis indicated that participants perceived the creative activity in terms of a multi-faceted core category of “creating connections to life”. This characterized connections concerning highly salient topics for the individual and daily life outside the nursing home. Three sub-categories were identified with separate characteristic features of engaging in creative activity. First, a “generous receptive environment”, highlighting the sociocultural setting as a necessary context for pursuing engagement in creative activity. Second, “Unfolding creations—an evolving process” encompasses the actual making, during which ideas in an ongoing process evolved into products. Third, “Reaching beyond for possible meaning horizons” captures aspects of meaning beyond the current conditions of the body and engagement in creative activity.

Figure 1 graphically illustrates the features and their relative disposition to one another. The arrows illustrate the ongoing creation of connections to life outside the nursing home as a reciprocal process.

Figure 1.

A tentative illustration of the features of creative activity.

Results of the analyses are presented below; we first describe the three sub-categories and then return to reconsider the overall core category of “Creating connections to life”.

A generous receptive environment

A generous receptive environment was identified as a basic requisite for fostering engagement in creative activity. This environment was characterized as one that provides (a) freedom and support as the prime reason for being able (b) to contemplate and dare to engage in creative activity.

Freedom and support

The notion of a generous environment embraced simultaneous coexisting contrasts that defined a dialectic movement. For example, here we find the simultaneous presence of the active experiences of freedom in contrast to getting support and even a slightly “pushy” encouragement. This notion stands in contrast to one dimensional notions. Thus, the analytic unit of experience for participants must be seen to embrace the pairing and not one or other feature alone. Such culturally constructed categories cannot be reduced to smaller units without fundamentally changing or misrepresenting their meanings. One contribution of this study is to clarify dimensions for valid analytic units needed to advance our understandings of how and why creative activity is sought by participants and may produce positive effects. We next present the different aspects of freedom and support perceived by participants as central to creative activity.

Freedom as individual choice in contrast to routine care

For clients in a geriatric care facility there are limitations in personal space, as others decide daily routines and thereby restrict their degree of choice and influence. As Peter, aged 64 with incurable cancer, explained regarding the difference between the creative activities and other activities at the nursing home. “There is an enormous difference, actually, the creative activity is something I create myself, in the other activities it is others that have control over me, both movements and everything, and the time, even!” Thus, creating an object was valued as an opportunity to gain a sense of personal control and experience freedom made salient here given the institutional context.

Freedom as no demands

From the therapist’s perspective the notion of a generous environment was associated with an environment free of demands, where the clients could do as they liked. Here we see another aspect of the generous environment composed of awareness of socially situated simultaneous twin contrasts, namely freedom vs. limits imposed by health or institutional constraints. Several therapists spoke of creating a “demand free” arena as a conscious strategy for inviting the clients to pursue creative activity. As one of them said, “I believe it is important that you really give the patients the possibility to think for themselves and at their own pace and experience that it is okay not to do anything”. Engaging in crafts in such a demand-free environment allowed clients to find their own personal pace and an acceptance of individual rhythms.

“Demanding” support, a contrast in the environment of no demands

The environment of the workshops was intended by therapists to represent a “no demand” setting and yet in another regard the environment was highly socially, personally, and energy demanding with its ongoing activity and interaction. Analyses indicated a complex understanding of the notion of support incorporating several interrelated aspects. Kate, for example, described her experience of support: “I called and said I did not have the energy to come, so she said can’t you just come for a little while, you don’t have to do anything, just sit and talk. And slowly I realized that it was good. Even if I was here just for a little while, it felt great and meant a lot”. Here, even though the therapist appear mildly demanding she encourages the client to make explicit personal limits, and further validates those self-defined limits as acceptable, “welcome” in the group setting.

Therapists engaged with clients in their projects and in return stimulated the client’s own engagement. Thus support involved mutual engagement and to some degree implicitly demanded interdependence among participants. Clients talked about how there were no expectations, how they felt free to be and do as they liked, simultaneously with being supported and “pushed” to come. For example Peter, who earlier expressed his appreciation of freedom and no demands, told us “I find it so difficult to do anything, unbelievably difficult, I need someone to push me”. This reflection voiced the idea that demanding support was a valued need.

This complexity of balancing freedom and demands seemed key to the receptive generosity of the environment, growing out of mutual engagement by clients and therapist and allowing individuality.

Daring to create

Daring to create was an important feature embraced by the generous environment for becoming involved with creating, because engaging in creative activity involved both courage and risk-taking. For the clients daring to create was imbued with stepping over a strong personal threshold or barrier. This involved, they explained, juggling two needs, realizing they had inner barriers to overcome to engage in the creative activities, and also recognizing that they possessed a drive in wanting to create. Notably, for these clients with serious or terminal health conditions to assume a “daring” stance required confrontation of multiple thresholds (current and lifelong) given their life and institutional setting, which emphasizes “care”, protection, and personal fragility. In daring, the clients talked about the risk of failure that the creation would not turn out as they hoped. They accentuated elements of not believing that they could do it. Kate expressed her experience of daring and getting started with creative activity as she said, “I felt foreign. … I could never paint, it was difficult in school because I thought that everyone else was creative, but I could never do anything … ‘it will probably turn out crazy, but it doesn’t’, those are the kind of thoughts you have in the beginning, that this will not succeed”. This shows how daring involved getting in touch with difficulties concerning insecurity and expectations. This is daring indeed. It requires positive activation of personal resources and enabling social support to address more lifelong individual self-images and predilections in the face of serious health problems late in life.

Therapists, too, said daring was required as their thresholds for when to initiate activity were challenged. For example, to engage the clients, therapists actively tried to give them time by waiting for them until they were ready to engage. To do as little as possible in a professional position seemed provocative to the therapist—despite the fact that they used “waiting” as an active strategy fostering a generous environment. In the words of one therapist, “it is very much about having patience, daring to wait, we are often so busy that we go ahead of the patients and start off things because …we want to perform as well, I suppose”. “In my perspective as a therapist, I think it is about daring to wait in order to do right.” Clearly, anxiety over failing was also an issue for the therapists as they strove to perform professional roles. It further highlights how basic aspects of the taken-for-granted world are bracketed and called into question, including implicit notions of time and duration, as well as professional roles and practices.

While striving to engage the clients, therapists were aware of the challenge this represented to the clients. One therapist captured this when she said, “for the patients, it is about daring to take the step, the step over the threshold, daring to try again and daring to fail. It is very much about daring to take life back.” Hence, daring was referred not only to the threshold of creative activity, but most importantly to “taking life back” by engaging actively and thereby taking the risk of committing to envisioning a current life and a possible future.

These results highlight how the generous environment can be viewed as a co-construction through mutual investment from therapist and client. The generous environment provided a positive space that also embraced difficult experiences of ambivalence in the process of engaging in creative activity leading to salient existential questions that motivate and structure the constructive aspects of creative engagements. This means that the environment served as a facilitator for wrestling with the difficulties and wishes that clients deal with in pursuing engagement and connection to life, while living with fatal disease.

Unfolding creations—an evolving process

Engaging in creative activity was recognized as an unfolding of creations in an evolving process occurring in two levels: (a) the production of a material creation and (b) a process of individual development. The term “unfolding” conveys immersion in the process and step-wise exploration towards a not fully known endpoint, in contrast to constructing a predefined object and following already established or known “blueprint” instructions. The creative process concerned with the concrete creation is captured by three ongoing modes, starting with ideation, when getting the idea for what to create; then making, giving shape in crafting the creation; and finally, the evolving result. For the individual, the unfolding creative process was identified as motivated by a feature of not knowing how creations would turn out, even when starting out from predefined instructions. This part of the process also showed a personal aspect as the creative process gave each person ways to unfold and share something of themselves.

Not knowing as motivating

Through involvement in creative activities clients entered into a process of creating something that was not present before coming to the workshop. It involved following something as it grew and not knowing how the creation would turn out. As Tom said, “Often the first idea you have ends up changing quite a lot, the end product does not turn out as one thought from the beginning”. This quote illuminates how not knowing how the creation will unfold is a feature pervading the process of creating and indicates an acceptance of this uncertainty.

Another feature of not knowing was identified through remarks such as the following: “You feel locked in some way. Just as you let go and experience that there does not have to be a result from the beginning, it can develop as you create in the process and that gives peace in the body.” Here, objectifying and giving licence to “uncertainty” in the evolution of creative projects can possibly mirror, in contra-distinction, the implications of a client’s uncertain medical condition.

The element of not knowing created an element of suspense, as Lisa said about firing clay creations in the kiln “The colours are important, it is exciting how they turn out. It is always exciting every time something is taken out of the oven”. Here the excitement of not knowing is stimulating engagement.

Sources of joy

The creative process from ideation to making and to the final result stimulated joy.

In ideation, joy was evoked through reflective play with ideas. As Pete said, “I play with ideas very much … I engage in it.… I was walking in the forest at home, I am not sure where the idea came from, I must have walked by something or seen something.” This shows how being innovative occupies the mind, not only whilst in the therapeutic setting but also in the intervening time.

The process of unfolding a creation involved becoming deeply engaged and forgetting time, giving temporary respite from worries and concern about the illness. As Lisa said, “You forget your illness very much … you become happy.” So, the creative activity accentuated a change of focus and contributed to experiences of profound joy.

In making creations, joy emerged through sensory meeting with the material. This was emphasized by the participants as they spoke of purely doing, to make something in a practical manner, and experiencing a creation growing from the work with their hands and body made them feel happy. As Neil said, “Yes, happy, you become happy when you use your body as it is supposed to be used”. This draws attention to a bodily dimension and possible underlying problems of facing the fact that the disease interferes with or limits the ability to use the body as it is normally supposed to be used.

Also the creations that unfolded became valuable sources of joy in the form of a final product. The clients spoke with pride of having produced something purposeful and worthwhile. As Lisa remarked, “I made a bowl, which my husband took home. It was not so bad. I glazed it and fired it and then we put glass in the bottom and fired it one more time and it turned out to be very beautiful”. Here the result achieved was a source of pride and satisfaction.

Therapists emphasized how they actively tried to enable clients to experience feelings of “I can” success, meaning that they can be active and capable of creating something despite their current situation. When creations did not turn out as hoped clients and therapists found others ways to make use of them, for example by making chutney out of tomatoes that did not ripen.

Joy was experienced at giving creations away as presents and making others happy. As Kate shared how she had created a game for her grandchild, “ What was great fun was that I made this wooden game for my oldest granddaughter and she found it so much fun and was really happy that Christmas … it took a little while before she mastered the game, it is not as much fun today, but she says ‘when I don’t have anything to do I take it out and play by myself”. This shows the value of being able to continue participation in cultural traditions of giving gifts and receiving recognition and appreciation. As a therapist pointed out, giving the creations away is also a way for the clients to give something back, back to those from whom they receive concern and care.

Sharing in companionship

Unfolding creations included a strong social component. When engaging in creative activity alongside others a natural meeting place was formed. The social relations were framed in a process of actual doing. There was a reason to be there apart from just sitting and talking. The process of unfolding provided experiences that in themselves gave material for conversation with others, particularly not only related to health problems. A therapist explained, “it becomes a very good conversation .. . when you do something together you also talk about other things more than you might do when you train for specific functions”. This indicates that being together while creating something can ease conversation and the sharing of more in-depth personal issues.

While engaged in the creative process and ongoing conversations the participants unfolded and shared their individual life stories with each other. Through the activities clients could express themselves in a more concrete way. For example Lena explained, “you consider colours . .. I chose to use the rust-brown and red .. . my best time was when we lived in Africa, much of it comes back”. Choosing these colours of Africa reminded her of the best years of her life and memories from that experience became embedded in the creation. Furthermore, the creation provided an occasion to share some of that experience. As illustrated, unfolding of creations can provide a vehicle for sharing and the building of companionship as the participants followed each other’s challenges of engaging in creative activity and in handling their individual course of life with illness.

Reaching beyond for possible meaning horizons

Engaging in creative activity had implications reaching beyond the tangible act of making creations. It included reaching for possible future and alternative meaning horizons. This category was characterized as “actions for dreams, endings and new beginnings”, including actions on a concrete level and actions as symbolic representations.

Actions for dreams, possible endings, and new beginnings

Engaging in creative activity involved planning. For an idea or a vision of something to be accomplished a plan had to be made. Thus, creations had the potential to reach beyond the activity in a very immediate way by being incorporated into a plan. The creations were given further life, directly pointing ahead according to the plan. As one of the therapists said, quoting a client, “pottery … imagine if I could make a bowl, that would surprise my wife, yes I will do it” and the therapist commented, “She wouldn’t believe her eyes, was my interpretation”. Here plans provided something to look forward to. Rita gave us a telling example, “I am working on a stool, I am going to use it when I come home…. I shall try all I can to get well this winter, because the goal is to go to the cabin in the summer.” Here, plans are important in motivating and implying hope for a possible future.

Reaching beyond for possible meaning horizons indicates a feature of symbolic representations embodied in the creations. Thus the creations could be seen to carry symbolic meaning, if perceived as actions or representations of dreams, as possible endings, or as new beginnings. For example, clients created objects representing how life could have been or might become. This was illustrated by a therapist’s story of one her clients. “She painted a lot, sat and did sketches. She had one of these dolls where you see the proportions … arms and legs, and then she dressed her up. Sometimes she was a girl dancing ballet, I guess she did that herself in her youth. Then she was careful to give her eyebrows because she herself had no eyebrows now, so much of what she did not have or could not do any more she created in her paintings.” This example may illustrate both dreams of what once was, and also the client’s dreams for the present or a possible future.

Reaching an understanding that the creative activities could provide material representations of possible future and alternative-meaning horizons beyond concrete creations and the client’s current situation was central in this category. Also, reaching beyond the boundaries of this life was mentioned. One of the therapists told us of a woman with terminal cancer, who first was hesitant to try out any of the creative activities offered and then returned and said she wanted to mould soaps. She then made two soaps in the morning and returned the same afternoon to finish them as presents for her daughter that evening. Next she wanted to make another soap and experimented by putting a coloured scrap picture of an angel into the soap. That was the last time she visited the workshop before she died. As seen in this story the creation could symbolize the coming death and be a way to symbolically communicate regarding horizons beyond. Another way of reaching beyond was the common desire to create things that could “live on” such as plants or things for grandchildren. In some aspect creations could be seen as a legacy, as one therapist said: “Maybe it is not just to express oneself but also to still exist in a symbolic way” so the creations live on in the possible future.

Creating connections to life

The most prominent feature in the findings was identified as “creating connections to life”. It stands out as the core category in the results because variations of this appear as a recurring theme throughout the results and the three sub-categories.

In the first sub-category of a generous environment, connections to life are seen as the generous environment enables clients to actively re-engage in life, while facing the fact that life is actually moving towards its end. In the second sub-category of unfolding creations from playing with ideas and crafting the creation to a final result, connections to life are made as both clients and therapists use life outside the nursing home, in the community, to find purpose for the creative work. Also, there are connections on a more personal level as the unfolding of creations becomes a medium for sharing and giving.

In the third sub-category of reaching beyond for possible horizons, the connections to life are made as plans connecting to people and events outside the nursing home and as symbolic representations for the individual client’s life.

Through making creations, clients created connections to life by not just being a client in the healthcare system but rather a whole person with a whole life.

Being oneself

By creating connections between usual life outside the nursing home and what one is doing at the nursing home, everyday experiences in multiple contexts were drawn together. In doing so, the clients found ways of being themselves and reclaiming their full adult personhood. Being able to be and bring oneself into the world of the nursing home, and the healthcare system, by choosing colours, and expressing personal opinions and predilections, becomes a way of staying or becoming connected to life. Most of all it provides the client with opportunities not only to be a client but also to be oneself, the person that was there before and still exists. As Pete told us,“I was active all my life so it was very difficult when I got sick. I can barely saw wood, then I become so tired in my shoulder … my life changed … totally. This is very positive because this is … a lifeline for me to come here . .. meet a few people and engage in activity.” The client is sharing his loss of being an active full adult person as he has been all his life and relating how he is partially regaining it by connecting or reconnecting to it through participating in the creative activity workshops.

Engaging in creative activity appeared to enable the creation of connections with regard to a larger sense of being oneself. This is further illustrated in a story told by a therapist about a client who refused to have an interview with a doctor in the nursing home. “ We had a client who did not want to meet the doctor and something came up so he came down and there they sat. It was a woman who absolutely refused to deal with the doctor and then she talked a lot with him. The others were working and it was so obvious that he also thought this was so good. It became a more free and relaxed conversation in this setting.” Here the environment at the workshop gave a very different context for the interview, in which the patient could be a whole person rather than a patient in relation to the doctor.

The meaning of creating connections to life is seen as functioning on many levels, to be in contact with one’s roles, sense of identity, and earlier experiences, but also to stay connected in life and to know you are alive and living, despite serious illness. As one therapist said “They are still in shock many of the clients I work with, but to offer a little reality and something of ‘life outside’ … wake a little hope that it works to return after or with disease”. In this way engaging in creative activity at the workshop grew into being about life rather than a component of nursing home treatment.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to discover and characterize components of engagement in creative activity as occupational therapy for elderly people dealing with life-threatening illness, from the perspective of both clients and therapists.

One interesting contribution of this study was identification of the construct of “creating connections to life”, which was recognized as being made throughout the process of engaging in creative activity. This finding should be interpreted with some attention to the possibility that this could indicate the clients were disconnected before engaging in creative activity or that there was a need to reconnect or stay connected.

The clients in this study were all faced by life-threatening illness, which might distance them from their earlier roles, occupations, and social networks. Yet, participation in the creative workshop at the nursing home was not primarily about illness. The results showed that it provided opportunity for the creation of connections in several ways. By drawing up and refashioning memories and experiences from the client’s life both therapists and participants in the workshop re-established and supported the clients as individuals rather than in their roles as clients. This relates to the shaping of self as proposed by Bateson (31). Thus, as creations are connected to the client’s life they provide an opportunity to express and strengthen the sense of self and thereby reduce what Michael Bury (7,32) characterized as a root cause of distress in illness, the biographical disruption.

Furthermore, the engagement in creative activities enabled clients to make connections between past experiences and their present situation and possible future. Ricoeur (20) uses the notion of emplotment for the quality of narrative that links different experiences and events with each other into meaningful units, and thereby gives explanations and meaning to lived experiences. In line with such reasoning, the present results can be understood as a way to create narrative meaning in a non-verbal idiom of creative acts. The story emerges in observable sets of habit structures, which are expressive of current health and life transitions people are living (33). Thus, the crafts need to be understood in terms of how each individual creation represents a story embedded with meanings that the individual person invests in constructing his/her creation. This interpretation is supported in the finding of sharing, whereby the clients shared individual stories in “doing” creations rather than in spoken language. Maybe creations even give a more authentic reflection of the individual person and access to the meaning of human action than do verbal narratives, which are reflected stories of experiences.

In the above reasoning we argued that creative activities were not primarily about the disease. However, the connections to life were made in the presence of the disease and thus had a far more salient existential meaning reaching beyond the present life situation. Most of the clients at the workshop had life-threatening diseases such as cancer. The creative activities were used as a way to communicate and also to address the future concretely. Such an understanding enriches notions of creative activities to enable links to the individual’s everyday life before, now, and in a possible future. For example, the things created often carried meanings that could be interpreted as communicating issues around death and possible new beginnings. The story of the woman who made soap containing an angel is an example of this. In addition, this directs attention to our understanding of the clients’ notion of “creating connections to life”. When the clients may be connecting into a possible future they may also simultaneously be disconnecting from the life that was. That is, using their hands to shape materials in the creative projects includes processes of disintegrating, breaking, and catabolism (reshaping clay, moulding soap, etc.), which may lead to another kind of freedom that is vital to reorganizing and letting go.

The importance of reworking connections when dealing with life-threatening illness and enabling strategies for such work has not yet received adequate attention. However, it has been argued that patients confronted with impending death want to be seen as whole persons, not fragmented or known by a disease entity (33,34). In the light of such an argument, the creation of connections to one’s usual life by engaging in creative activity can be a possible strategy for patients to use to overcome fragmentation. Further, creating connections can be a strategy for dealing with experiencing loss in trying to gain/ reach transcendence. In this context, transcendence implies re-evaluation and an acceptance of self by taking action (8,23).

A prominent result was identification of the generous environment as a prerequisite for engagement in creative occupation. Both therapists and clients highlighted that creative activity was not easy. Rather there was a risk in striving to engage in creative activities. May (16) addresses the courage needed for humans to create as it is about something new and involves entering new territory. He accentuates a paradox given that an immanent need and desire nurture creative activity. This paradox could be seen to be reflected in the findings of this study, as the creative activities were a side of positive experiences also seen as requiring courage involving difficult emotions. Consequently a generous environment that embraces the existence of contrasts was needed in order to foster participation. This finding has clinical implications suggesting that involvement of professional therapists might be a necessity in order to make participation in such occupations possible for individuals with serious disease.

Clients can accomplish a lot of things within these creative projects. They can confront or deny their illness, take a time-out, or do all these things at the same time. There is no simple formula, statistic, or blunt reduction to measure “coping” or “loneliness” in these activities. People (therapists and their clients) create a loose and open psychological space—a space locally engendered as a “supportive environment” and a welcoming attitude within which possibilities exist for playfully reviewing life, making connections to one’s culture, society, and communities, not just “making peace” with others, making new friends, or artistic expression. This corresponds to the work of Winnicott (35), who proposes a potential space as the grounds for creative and playful occupations. However, Winnicott does not address how to gain entrance to the potential space. The findings in this study add knowledge for the understanding of components necessary for establishing a space or therapeutic environment in which creative work and acts of defining and reconstructing meaningful connections to cultural traditions and life in the community can take place.

A primary benefit of engaging in creative activity was identified as experience of joy. According to May (16) the experience of joy is related to feelings of increased awareness and realization of one’s resources. Similar ideas are suggested by Csikszentmihalyi and Parham who point to attributes such as ease, happiness, and experiences of pleasure in the here and now as being health promoting (10,36). Therefore the empirical findings of joy in our study can indicate creative activity as a vehicle for the experience associated with increased competence and health. This is consistent with studies on health and well-being in older adults that found a high correlation with hobbies, use of leisure time, and spiritual pursuits contributing to a more meaningful and fulfilling life (7,10,37).

However, engagement in the creative activities was not exclusively positive. It also involved facing difficult existential issues. Therefore we argue that creative activity as intervention is perhaps the closest to activity that represents “normal” life for clients within the healthcare system.

Methodological considerations

An objection that might be raised against this study is that the participants all had chosen to engage in creative activity. Thus the population could be considered to be biased, as people who did not choose to engage in such activity were not approached. However, the focus of the study was intended to be on engagement in creative activity and thus the chosen population seemed appropriate. Yet it raises a need for further research also involving clients who choose not to participate in creative activities, to reach a deeper understanding of creativity for people facing the last stages of life.

Since this is an exploratory study of 15 participants from the same setting, the results can not be generalized directly to other groups in similar settings. Primarily the results are indicative of how and why engaging in creative activity can be of importance. We interviewed the participants only once and this raises a need to strengthen our findings by further research, examining if and how the impact of engaging in creative activity might be different or consistent over a longer period, as it is over time that dealing with disease takes place.

Conclusion

Returning to the aim posed at the beginning of this paper, the results of our study demonstrate foundations for connecting, disconnecting, and rearranging connections to life by confronting and working through psychosocial developmental issues, particularly at the end of life, and also grief and mourning within the context of encountering fundamental life disruptions from life-threatening illnesses. Clearly, engaging in creative activity holds the potential for clients to confront and rebuild attachments to core cultural ideals and values as well as social relationships, not just with physically present people, but also remembered and idealized social others including their own past identities and self-images that are brought forward again to engage contemporary challenges.

A merit of this study is its presentation of combined perspectives from therapists and clients, which draw attention to clinical implications. This combination highlights not only the collaborative foundation for establishing a generous environment, but also the dynamics between participants necessary for the creation of connections to everyday life. Indeed these findings are only in their infancy and more research is needed to explore and build a solid foundation of theoretical knowledge for the use of creative activities in therapeutic practice.

Table I.

Data on patients and therapists

| Patients |

Therapists |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age | Diagnosis | Profession | Social | Activity | Gender | Age | Worked at place of research site |

|

| 1. | Male | 70 | Meningioma & stroke |

Exhibitor | Wife & son | Woodwork | Female | 44 | 1.5 years |

| 2. | Male | 63 | Cancer, myeloma | Fireman | Divorced, daughter | Ceramics, woodwork etc | Female | 44 | 2 years |

| 3. | Female | 72 | Cancer, breast | Chemist | Husband & son | Ceramics, gardening & silk paint |

Female | 40 | 2 years |

| 4. | Female | 62 | Cancer, breast | Community worker & housewife |

Husband son & daughter | Textile | Female | 42 | 6.5 years |

| 5. | Male | 60 | Stroke/hepatitis | Florist–decorator | Single Early retirement | Ceramics | Female | 30 | 6.5 years |

| 6. | Female | 67 | Cancer | Teacher of physiology |

Single | Silk paint, soap, paper, plant colour and knitting |

Female | 31 | 1 year |

| 7. | Female | Cancer | Printer | Single | Woodwork & gardening | Female | 51 | 10 | |

| 8. | Male | 89 | Cancer | Policeman | Wife & two sons | Ceramics | |||

Acknowledgements

Stockholm County Councils Research Programme “Arts in Hospital and Care as Culture”, the Association for Cancer and Traffic Victims in Sweden, the Karolinska Institute and the Occupational Therapy association in Denmark supported this study.

References

- 1.Thompson M, Blair S. Creative arts in occupational therapy: Ancient history or contemporary practice? Occup Ther Int. 1998;5:49–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kielhofner G. Conceptual foundations of occupational therapy. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mishler EG. Storylines: Craftartists’ narratives of identity. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osgood NJ. Suicide in later life. New York: Macmillan; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sviden G, Borell L. Experience of being occupied—some elderly people’s positive experiences of occupations at community-based activity centers. Scand J Occup Ther. 1998;5:133–139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bygren LO, Konlaan BB, Johansson SE. Attendance at cultural event, reading books or periodicals and making music or singing in a choir as determinants for survival. Br Med J. 1996;313:1577–1580. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7072.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zemke R, Clark F. Occupational science: The evolving discipline. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker G. Disrupted lives: How people create meaning in a chaotic world. Berkley: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christiansen C. Defining lives—occupation as identity: An essay on competence, coherence and the creation of meaning: Eleanor Slagle Lecture. Am J Occup Ther. 1999;53:547–559. doi: 10.5014/ajot.53.6.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Csikszentmihalyi M. Activity and happiness: Towards a science of occupation. Jour Occup Sci: Aust. 1993;1:38–42. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruner J. Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olofsson KB. I Lekens Värld (In the world of [lay) Sweden: Berlings Arlöv; 1994. in Swedish. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leontjev AN. Virksomhed—Bevidsthed—Personlighed (Enterprise—consciousness—personality) Copenhagen: Sput-nik/proges; 1983. in Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly M. Play as exploratory learning. Beverly Hills: Sage; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer A. The philosophy of occupational therapy. Am J Occup Ther 1922. 1977;31:639–642. Reprinted. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.May R. Modet att skapa (The courage to create) Stockholm: Natur och kultur; 1994. in Swedish. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohler B. Life story and the study of resilience and response to adversity. J Narrative and Life History. 1991;1:169–200. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattingly C. Healing dramas and clinical plots: The narrative structure of experience. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Polkinghorne DE. Narrative knowing and the human sciences. Albany: State University of New York Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricour P. Time and narrative. II. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Simonton D. Creativity in the later years. The Gerontologist. 1990;30:326–31. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luborsky M. Creative challenges and the construction of meaningful life narratives. In: Adams-Price CE, editor. Creativity and successful aging: Theoretical and empirical approaches. New York: Springer; 1998. pp. 311–337. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotre J. Outliving the self: Generativity and the interpretation of lives. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luborsky M. The retirement process: Making the person and culture malleable. Med Anthropol Q. 1995;8:411–429. doi: 10.1525/maq.1994.8.4.02a00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simonton D. The swan song phenomenon—last work effects for 172 classical composers. Psychology and Aging. 1998;4:42–47. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.4.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konlaan BB. Cultural experience and health: The coherence of health and leisure time activities, Dissertation. Umea: Solfjadern Offset AB; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds F. Coping with chronic illness and disability through creative needlecraft. Br J Occup Ther. 1997:60. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Persson D. Flow and play in an activity group—a case study of creative occupations with chronic pain patients. Scand J Occup Ther. 1996;3:33–42. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kvale S. Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bateson G. Ånd og Natur (Spirit and nature) Copenhagen: Rosinante/Munksgaard; 1991. in Danish. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 1982;4:167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baily S. The arts in spiritual care. Semin Oncol Nurs. 1997;13:242–247. doi: 10.1016/s0749-2081(97)80018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luborsky M. The cultural adversity of physical disability: Erosion of full adult personhood. J Aging Studies. 1994;8:239–253. doi: 10.1016/0890-4065(94)90002-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winnecott DW. Playing and reality. London: Tavistock Publications; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parham D. Perspectives on play. In: Zemke R, Clark F, editors. Occupational science: The evolving discipline. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1996. pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iwarsson S, Isacsson Å, Persson D, Scherstén B. Occupation and survival: A 25-year follow-up study of an aging Swedish population. Am J Occup Ther. 1998;52:65–70. doi: 10.5014/ajot.52.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]