Abstract

Background and Aims

Stomatal density (SD) generally decreases with rising atmospheric CO2 concentration, Ca. However, SD is also affected by light, air humidity and drought, all under systemic signalling from older leaves. This makes our understanding of how Ca controls SD incomplete. This study tested the hypotheses that SD is affected by the internal CO2 concentration of the leaf, Ci, rather than Ca, and that cotyledons, as the first plant assimilation organs, lack the systemic signal.

Methods

Sunflower (Helianthus annuus), beech (Fagus sylvatica), arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) and garden cress (Lepidium sativum) were grown under contrasting environmental conditions that affected Ci while Ca was kept constant. The SD, pavement cell density (PCD) and stomatal index (SI) responses to Ci in cotyledons and the first leaves of garden cress were compared. 13C abundance (δ13C) in leaf dry matter was used to estimate the effective Ci during leaf development. The SD was estimated from leaf imprints.

Key Results

SD correlated negatively with Ci in leaves of all four species and under three different treatments (irradiance, abscisic acid and osmotic stress). PCD in arabidopsis and garden cress responded similarly, so that SI was largely unaffected. However, SD and PCD of cotyledons were insensitive to Ci, indicating an essential role for systemic signalling.

Conclusions

It is proposed that Ci or a Ci-linked factor plays an important role in modulating SD and PCD during epidermis development and leaf expansion. The absence of a Ci–SD relationship in the cotyledons of garden cress indicates the key role of lower-insertion CO2 assimilation organs in signal perception and its long-distance transport.

Keywords: Stomatal density, stomata development, pavement cells, cotyledons, leaf internal CO2, 13C discrimination, Lepidium sativum, Helianthus annuus, Fagus sylvatica, Arabidopsis thaliana

INTRODUCTION

Stomata are pores, which can vary in aperture, on plant surfaces exposed to the air: they control water and CO2 exchange between plants and the atmosphere. Globally, about 17 % of atmospheric CO2 enters the terrestrial vegetation through stomata and is fixed as gross photosynthesis each year. Water in the earth's atmosphere is replaced more than twice a year by stomata-controlled transpiration (Hetherington and Woodward, 2003). For plants to survive in a changing environment, stomata must be able to respond to environmental stimuli. Their long-term (days to millennia) response manifests itself through variations of stomatal density (SD, number of stomata per unit of leaf area) and/or size, whereas their short-term dynamics derive from changes in the width of the pores' apertures, at a time scale of minutes. The effect of atmospheric CO2 concentration on both SD and stomatal opening has been recognized (Woodward, 1987; Mott, 1988; Woodward and Bazzaz, 1988; Morison, 1998; Hetherington and Woodward, 2003; Franks and Beerling, 2009), used in reconstruction of paleoclimate (Retallack, 2001; Royer, 2001; Royer et al., 2001; Beerling and Royer, 2002; Beerling et al., 2002) and subjected to meta-analysis (Ainsworth and Rogers, 2007). It is well known that stomatal guard cells respond to the internal CO2 concentration (Ci) of the leaf rather than to the external CO2 concentration: pores open when Ci falls and close when it goes up (Mott, 1988; Willmer, 1988; Mott, 2009). It is tempting to speculate that similar sensing of Ci may also act during the final setting of SD in mature leaves: it seems more plausible that the frequency of the supply ‘valves’ is controlled by chloroplast-mediated CO2 demand than by globally modulated availability of CO2 in the free atmosphere. However, to our knowledge, there are no experiments on the relationship of SD to internal CO2.

Recently, our knowledge of how stomatal frequency is controlled at the genetic level (Nadeau and Sack, 2003; Coupe et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2007) and in response to CO2 (Gray et al., 2000; Bergmann, 2006; Casson and Gray, 2008; Hu et al., 2010) has increased considerably, but the nature and location of the putative CO2 sensor remain unresolved. Development of stomata considerably precedes leaf unfolding, and most stomata are already developed before the leaf reaches 10–20 % of its final area, when SD reaches its maximum (Tichá, 1982; Pantin et al., 2012). At that stage of ontogeny, stomata and their cell precursors experience a local atmosphere that is probably more humid and enriched in respired CO2 than ambient air. Sensing of the free atmospheric environment is thus unlikely. In addition to atmospheric CO2, other external signals affect SD, among them irradiance, atmospheric and soil water content, temperature, and phosphorus and nitrogen nutrition (Schoch et al., 1980; Bakker, 1991; Abrams, 1994; Sun et al., 2003; Thomas et al., 2004; Lake and Woodward, 2008; Sekiya and Yano, 2008; Xu and Zhou, 2008; Fraser et al., 2009; Figueroa et al., 2010; Yan et al., 2012). It is useful to distinguish between the different steps of stomatal development that may be affected by the external cues, i.e. whether it is, on the one hand, the division of protodermal or meristemoid cells leading toward guard cell and pavement cell formation, or, on the other, the enlargement of already existing guard cells and pavement cells during leaf growth that is affected. Stimulation of the first group of processes usually leads to a change in the fraction of stomata among all epidermal cells [stomatal index (SI)], whereas the proportional enlargement of stomata and pavement cells during leaf expansion reduces SD and pavement cell density (PCD), and increases the maximal stomatal size and aperture. However, both developmental phases overlap (Asl et al., 2011).

In young leaves that are still metabolically supported by mature leaves, the signal about conditions in the free atmosphere may come from mature leaves (Lake et al., 2001; Miyazawa et al., 2006). A pivotal role in the signal has been attributed to abscisic acid (ABA) (Lake and Woodward, 2008) or the 13C content (δ13C) in assimilates (Sekiya and Yano, 2008). (For the sake of simplicity, we omit the ‘13C’ after δ from here on since carbon is the only element whose stable isotopes are considered here. Also, internal CO2 refers to the CO2 within the organ.) The degree of carbon isotope discrimination is considered a ‘fingerprint’ of the ratio of internal CO2 concentration over ambient CO2, Ci/Ca, which is negatively proportional to intrinsic water-use efficiency (WUE; Farquhar and Richards, 1984). However, what substitutes for the role of a signal derived from older leaves in the first ever phototrophic organ in a plant's life, the cotyledon? The information on Ci/Ca experienced by the maternal generation could be delivered to cotyledons via assimilates stored in the seed. Alternatively, SD in cotyledons could be controlled by the local environment of primordial cotyledons.

Here, we tested (1) whether the density of stomata on fully developed true leaves is sensitive to ambient or internal CO2 concentration. We manipulated Ci by changing various environmental factors affecting photosynthetic rate and/or stomatal aperture (light quantity, ABA and osmotic stress) while keeping ambient CO2 constant during the plant's growth. Four species were used for testing this question. In two species, we also investigated the Ci response of pavement cells and calculated the SI. Data from the literature for 16 plant species cultivated under different growth conditions were analysed to complement these experiments. Further, we wanted to know (2) whether SD in cotyledons is controlled by CO2 in a way similar to that in true leaves. To manipulate Ci, we grew the plants at various Ca in mixed artificial atmospheres of air or helox [a mixture of gases similar to air but with nitrogen substituted by helium; CO2 diffuses 2·3 times faster in helox than in air which can increase Ci (Parkhurst and Mott, 1990)] and at reduced total pressure of ambient atmosphere. Ci was estimated from the carbon isotope composition (δ) of leaf dry mass.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plants and growth conditions

Experiment 1: mature leaves at invariant Ca

The SD of mature true leaves was estimated in three plant species (sunflower, Helianthus annuus; arabidopsis, Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes Columbia and C24; and garden cress, Lepidium sativum) grown in a growth chamber (Fitotron, Sanyo, UK). Leaf samples of beech (Fagus sylvatica) were collected from a 60-year-old tree growing at a meadow–forest ecotone, from deeply shaded and sun-exposed parts of the crown. Sampling was organized in the course of two seasons (May–October 2007 and 2009) in 2- to 3-week intervals within a single tree in order to eliminate any genetic effects in the seasonal course of Ci. Groups of sunflower and garden cress plants were also treated with ABA or polyethylene glycol (PEG) added to the root medium in order to manipulate Ci via stomatal conductance. All plants were exposed to a free atmospheric CO2 concentration of about 390 μmol mol–1. Plants cultivated in growth chambers experienced 60 % relative air humidity, day/night temperatures of 25/20 °C and a 16 h photoperiod. The high-light and low-light treatments were species specific. Sunflower was grown at irradiances [photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD)] of 700 μmol m–2 s–1 (high light) or 70 μmol m–2 s–1 (low light), both with the same spectral composition. After 5 weeks, the plants cultivated at each irradiance were divided into three sub-groups, and ABA [10–5 m, (+)-abscisic acid, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany] or PEG 6000 [5 % (w/w), Sigma-Aldrich, Germany] was added to the hydroponic solution in two sub-groups, leaving the third as the control. The solutions were renewed once a week. After 3 weeks, newly developed mature leaves were collected for carbon isotope analysis and estimation of SD. Arabidopsis plants were grown for 18 d at a PPFD of 200 or 80 μmol m–2 s–1 and the first rosette leaf was measured. Garden cress was grown from seeds in 100 mL pots in garden soil for 14 d at a PPFD of 500 μmol m–2 s–1. From the third day after germination, half of the plants were watered daily with 10 mL of water (controls) while the second half was given 10 mL of 10–4 m ABA solution per day. Beech leaves were collected eight and ten times during the seasons of 2007 and 2009, respectively. The shaded leaves were sampled from a part of the crown exposed to the north and facing the forest; the sun-exposed leaves were collected from the opposite side, facing a meadow. The average PPFD at sampling time (1300–1500 h) was 1301 (±384) and 33 (±19) μmol m–2 s–1 in the sun-exposed and shaded environment, respectively (PAR sensors and data loggers Minikin R, EMS, Brno, Czech Republic).

Experiment 2: cotyledons and true leaves in air and helox at variable Ca

The SD and PCD on cotyledons and first leaves of garden cress were compared in a set of controlled-atmosphere experiments. We chose garden cress because of its fast growth rate allowing us to reduce costs for compressed gases, mainly helium. The plants were grown for 14 d from seed in an artificial atmosphere in 600 mL glass desiccators, through which a gas flow of 500 mL min–1 was maintained. There were 10–30 plants germinated on wet silica sand or perlite in each desiccator. Each harvest on the seventh and 14th day after seed watering (DAW) reduced the number of plants by ten. Plants were watered in 2- to 3-d intervals with tap water or with half-strength nutrient solution. Desiccators were placed in a growth chamber (Fitotron, Sanyo, UK) and attached to a computer-controlled gas mixing device (Tylan, USA and ProCont, ZAT Easy Control, Czech Republic). Plants were grown at a PPFD of 400 μmol m–2 s–1, with a 16 h photoperiod and day and night air temperatures of 23–25 °C. A mixture of He and O2 at a v/v ratio of 79/21 (helox), or artificial air mixed from N2 and O2 at the same v/v ratio (air), with the addition of CO2 at one of three concentrations (180, 400 and 800 μmol mol–1) was fed into three parallel gas pathways to prepare one line with low humidity (60 ± 5 %; LH) and two separate high humidity (90 ± 5 %; HH) lines (using a two-channel dew point generator; Walz, Germany). The two gas mixtures differing in humidity flowed through two hermetically sealed desiccators with plants, arranged in parallel and having outlets open to the free atmosphere. The third pathway led the humid gas through a reducing valve into the third parallel desiccator with a vacuum pump attached to its outlet. This device allowed us to grow plants in the third desiccator at a total gas pressure reduced to one-half of that in the other two desiccators (hypobaric plants grown at pressure reduced to 450–500 hPa; RP). We included this hypobaric variant since plants grown at reduced total pressure operate at a Ci lower than what would have been expected for the given Ca (Körner et al., 1988). Gas mixtures were prepared from compressed He or N2 (both with a purity of 4·6), oxygen (3·5) and CO2 (20 % of CO2 in N2; all Messer, Czech Republic). The δ of the source CO2 was –28·2 ‰. CO2 and vapour concentrations were measured at the outlets of the desiccators with an IRGA (LiCor 6400; Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE, USA). The fractions of He and O2 in the outlet atmosphere were measured with an He/O2 analyser (Divesoft, Prague, Czech Republic) twice a day. Altogether, 18 treatments were applied: two different inert components of the gas mixture (He or N2), each with three different CO2 concentrations, and each in dry, humid and hypobaric variants (see Table 1). Different Ca, humidity, He instead of N2, and reduced pressure in gas mixtures were used to manipulate Ci, the growth-integrated value of which was estimated by 13C discrimination. Seven- and 14-day-old plants were harvested. For plants grown at 180 μmol mol–1 of ambient CO2, we also included harvest at 21 DAW.

Table 1.

Overview of the design of the four experiments presented

| Experiment no. | Species (ecotype) | Treatment (PPFD μmol m–2 s–1) | Sub-treatment | Ca (μmol mol–1) | Leaf age at harvest (d) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Helianthus annuus | HL (700) [↓] | Control | 390 | 56 |

| +PEG [↓] | |||||

| +ABA [↓] | |||||

| LL (70) [↑] | Control | ||||

| +PEG [↓] | |||||

| +ABA [↓] | |||||

| Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia, C24) | HL (200) [↓] | 390 | 18 | ||

| LL (80) [↑] | |||||

| Lepidium sativum | (500) | Control | 390 | 14 | |

| +ABA [↓] | |||||

| Fagus sylvatica | HL (1301) [↓] | Season, leaf age | 390 | 30–180 (18 harvests) | |

| LL (33) [↑] | |||||

| 2 | Lepidium sativum | Artificial air [↓] | LH [↓] | 180 [↓] | 7, 14, 21 |

| 400 | 7, 14 | ||||

| 800 [↑] | 7, 14 | ||||

| HH [↑] | 180 [↓] | 7, 14, 21 | |||

| 400 | 7, 14 | ||||

| 800 [↑] | 7, 14 | ||||

| RP [↓] | 180 [↓] | 7, 14, 21 | |||

| 400 | 7, 14 | ||||

| 800 [↑] | 7, 14 | ||||

| Helox [↑] | LH [↓] | 180 [↓] | 7, 14, 21 | ||

| 400 | 7, 14 | ||||

| 800 [↑] | 7, 14 | ||||

| HH [↑] | 180 [↓] | 7, 14, 21 | |||

| 400 | 7, 14 | ||||

| 800 [↑] | 7, 14 | ||||

| RP [↓] | 180 [↓] | 7, 14, 21 | |||

| 400 | 7, 14 | ||||

| 800 [↑] | 7, 14 | ||||

| 3 | Lepidium sativum | (100) [↑] | 390 | 21 | |

| (170) [↑] | |||||

| (240) [↑] | |||||

| (310) [↑] | |||||

| (380) control | |||||

| (450) [↓] | |||||

| (520) [↓] | |||||

| (590) [↓] | |||||

| 4 | Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia, C24) | HL (250) [↓] | 400 | 42 | |

| LL (25) [↑] |

HL, high light; LL, low light; HH, high humidity; LH, low humidity; RP, reduced pressure; PPFD, photosynthetic photon flux density during growth.

Expected effect of the treatment and sub-treatment on Ci: increase [↑] or decrease [↓] with respect to the counterpart treatment or control.

Experiment 3: cotyledons and true leaves at different PPFDs and invariant Ca

In the third type of experiment, garden cress was cultivated at eight different PPFDs in glass cuvettes (volume 100 mL) flushed with air pumped from outside of the building (Multi-Cultivator MC 1000, PSI, Brno, Czech Republic). Single plantlets grew in fine perlite in temperature-controlled cuvettes irradiated individually with white light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Plants were grown for 21 d at PPFDs of 100, 170, 240, 310, 380, 450, 520 and 590 μmol (photons) m–2 s–1, with a 16 h photoperiod and day/night air temperatures of 24/19 °C. The experiment was repeated six times.

Experiment 4: rosette leaves of arabidopsis at two different PPFDs and invariant Ca

Arabidopsis thaliana seeds, ecotypes Columbia Col-0 and C24, were incubated in the dark at 4 °C for 3 d. The plantlets were grown in soil in a growth chamber with a 10 h photoperiod, day and night temperatures of 18 and 15 °C, respectively, and air humidity of 50–70 %. Half of the plants were located on the upper shelf, closer to the fluorescence tubes, and exposed to high light (250 μmol m–2 s–1; HL). The other half were kept at the bottom of the same growth chamber and exposed to low light (25 μmol m–2 s–1; LL). Two independent repetitions with two different growth chambers (Sanyo, UK and Snijders Scientific, The Netherlands) were carried out. The carbon isotope composition of CO2 in the chamber atmosphere was spatially homogeneous due to active ventilation (mean over the growth time δ = –11·0 ‰). Stomata were counted on fully expanded leaves of 6-week-old plants which were used for 13C analysis. The designs of all four experiments are summarized in Table 1.

Stomatal density

The SD was estimated by light microscopy (Olympus BX61) on nail varnish imprints obtained directly from leaf surfaces (negatives) of adaxial and abaxial sides of mature leaves (only the abaxial side in beech). Cotyledons and first true leaves of 7-, 14- and 21-day-old garden cress and first rosette leaves of arabidopsis were investigated. Stomata and epidermal cells were counted on three plants per treatment, in each plant on adaxial and abaxial leaf and cotyledon sides. The cells on each side were counted in ten fields of 0·13 mm2 each, randomly distributed across the leaf (apex, middle part and base). The results were expressed as counts of stomata or pavement cells per mm2 of projected leaf area (total of adaxial and abaxial leaf sides), SD and PCD, respectively. The SI was calculated, where SD and PCD data were available, as SI(%) = SD/(SD + PCD) × 100.

Carbon isotope composition

The relative abundances of 13C over 12C (δ) were measured in leaf dry matter and, in expt 2 (garden cress in desiccators), also in seeds with testa removed (δs) and in the source CO2 (δa) used for mixing the artificial atmospheres. δa and δs were –28·19 ‰ and –28·13 ‰, respectively. δa of growth chamber air was also estimated but was not used in the calculation of the treatment-induced changes of Ci (see later). Leaves were oven-dried at 80 °C, ground to a fine powder, packed in tin capsules and oxidized in a stream of pure oxygen by flash combustion at 950 °C in the reactor of an elemental analyser (EA) (NC 2100 Soil, ThermoQuest CE Instruments, Rodano, Italy). After CO2 separation, the 13C/12C ratio (R) was detected via a continuous flow stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) (Delta plus XL, ThermoFinnigan, Bremen, Germany) connected on-line to the EA. The δ expressed in ‰ was calculated as the relative difference of sample and standard R: δ = (Rsample/Rstandard – 1) × 1000. VPDB (IAEA, Vienna, Austria) was used as the standard. Cellulose (IAEA-C3) and graphite (USGS 24) were also included to ascertain the reliability of the results. Standard deviations of δ estimated in laboratory standard were < 0·05 ‰.

Leaf intercellular CO2 concentration, Ci

We used the δ of leaf dry mass to evaluate the intercellular CO2 concentration integrated over the leaf's life time, Ci. The 13C discrimination during photosynthetic CO2 fixation, Δ, is related to Ci as (Farquhar et al., 1989):

| (1) |

where a and b are 13CO2 fractionations due to diffusion in the gas phase [4·4 ‰ in air and 2·0 ‰ in helox; see Farquhar et al. (1982) for derivation of a based on reduced molecular masses] and carboxylation by ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (Rubisco), excluding CO2 dissolution and intracellular diffusion (27 ‰), respectively, and Ca is the ambient CO2 concentration. Contributions of (photo)respiration to Δ were considered to be small and were neglected. Δ is related to 13C abundance in the plant, δp, and in air, δa, as Δ = (δa – δp)/[(δp/1000) + 1] where both δ and Δ are expressed in per mil (‰). The value of the denominator (δp/1000) + 1 does not deviate much from 1 and can be omitted here; therefore Δ ≅ (δa – δp) and rearrangement of eqn (1) for Ci yields:

| (2) |

In calculations of Ci in leaves grown in the free atmosphere and in artificial mixed atmospheres, we used δa –8·0 ‰ and –28·2 ‰, respectively. Since the air in growth chambers can be contaminated with the 13C-depleted air exhaled by people handling the plants, we calculated and plotted differences in Ci between the control and treated plants, rather than Ci itself. The advantage of this procedure is that the differences do not depend on δa provided that the control and treated plants grew in the same mixed atmosphere, such as in our growth chamber experiments:

| (3) |

where the subscripts t and c denote the treatment and control, respectively.

To calculate Ci in semi-autotrophic cotyledons, it was necessary to determine the fraction f of the cotyledons' carbon originating from the heterotrophic source (seed). We grew garden cress in artificial air or in helox with δ significantly different from free air. Our seeds, which were produced in free air conditions at δa close to –8 ‰ and had δs = –28·13 ‰, grew in glass desiccators supplied with artificial air or helox with δa = –28·19 ‰. With an increasing proportion of autotrophy and f decreasing below 1, δp decreased to values more negative than δs, with the sigmoid kinetics approaching a limit in fully autotrophic tissue with f = 0. Typically, 14- to 21-day-old true leaves had not yet changed their δp value [see Supplementary Data Fig. S3]. The sigmoid regressions of the δp time course were converted to the f course, ranging from 1 to 0, and used to determine f of 7- and 14-day-old cotyledons (see Appendix for more details). Ci of cotyledons grown in air or helox was then calculated with eqn (4) (derived in Appendix) as:

| (4) |

Statistical evaluation, meta-analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, s.d.), Pearson correlation and linear regression were calculated using SigmaPlot v. 11.0 (SigmaPlot for Windows, Systat Software, Inc.). Normality was checked using normal probability plots and with Shapiro–Wilk tests. Linear correlations and confidence intervals were analysed using probability thresholds of 5 % and 95 %, respectively. Standard error of the mean of SI (SEMSI) was calculated as the square root of the sum of squares of both partial derivatives of SI, each multiplied by the respective SD and PCD standard errors:

| (5) |

After substituting the derivatives this becomes

| (6) |

where the horizontal lines above SD and PCD denote the mean SD and PCD values. STATISTICA v. 8 (StatSoft Ltd., Tulsa, OK, USA) was used in the meta-analysis. The SD and related δ values were extracted from the available literature. Only those multifactorial studies were included in the meta-analysis where the environmental treatments were applied in a fully factorial design. Also, all studies on monocotyledons (grasses) were excluded from the meta-analysis as their SD can be governed by specific mechanisms.

RESULTS

The Ci response of stomatal density at invariant Ca

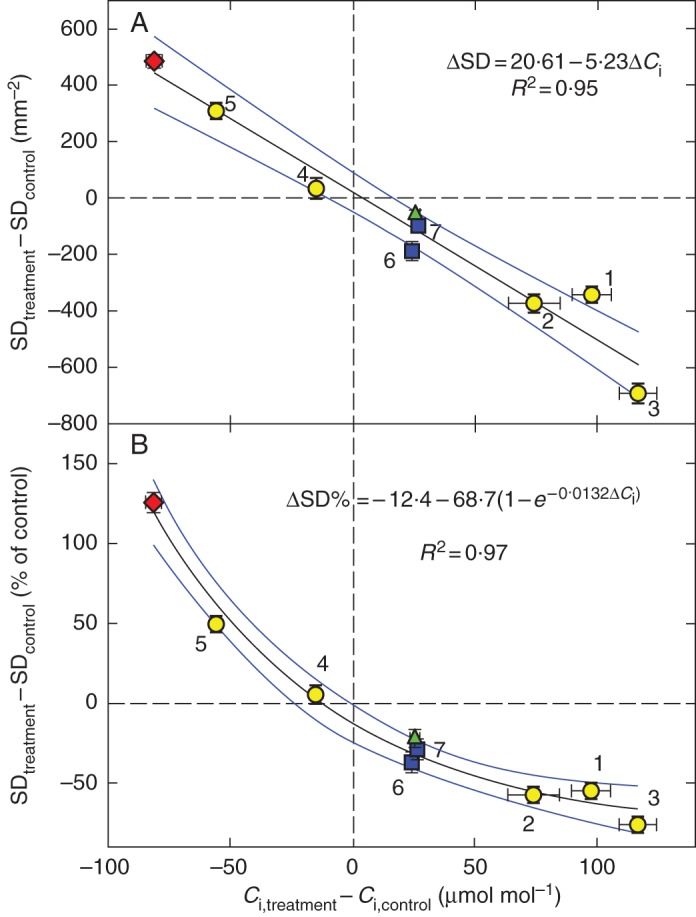

All investigated plant species responded to sub-optimal growth conditions with a change in the internal CO2 concentration of the leaf. Figure 1A shows that reduced irradiance increased Ci in shaded leaves compared with high-light controls in sunflower, beech and arabidopsis, and that there was a concomitant decrease in SD (see the points in the bottom right quadrant). The additional application of ABA or PEG to low-light-grown sunflower slightly modulated the Ci and SD deviations (points 2 and 3). Application of ABA or PEG to high-light-grown sunflower resulted in the opposite changes of Ci and SD to shading (points 4 and 5 in the upper left quadrant). The slope of the ΔSD∼ΔCi regression line is 5·23 (stomata) mm–2 μmol–1 (CO2) mol. It indicates the sensitivity of the apparent SD response to Ci. Since SD cannot reach zero or infinitely high values in a real plant, the Ci sensitivity applies only to the observed range of SD and should not be extrapolated. In order to overcome this limitation, we normalized the deviation of SD from the control (Fig. 1B). The relative decrement in SD with increasing Ci was attenuated exponentially, reaching an asymptote of –81·1 % for Ci approaching a theoretical limit 106 (pure CO2) and setting the limit of phenotypic plasticity in lowering SD to about 20 % of the original value.

Fig. 1.

Effects of shading and water stress treatments on internal CO2 concentration of the leaf, Ci, as inferred from the δ13C in leaf biomass, and on stomatal density SD. (A) Circles indicate increased (1, 2, 3) and decreased (4, 5) Ci, and concomitant changes in SD, under low light in sunflower grown in nutrient solution (1), with ABA (2) or PEG (3) added, and under high light in sunflower fed with ABA (4) or PEG (5). Values are differences between treatments and control, i.e. plants grown under high light in plain nutrient solution; nci = nSD = 6–8. The triangle shows the effect of shading on beech leaves (single tree, sampled during the 2007 and 2009 seasons, nci = 18, nSD = 20). Squares depict the shading effect in Arabidopsis thaliana rosette leaves grown for 18 d at irradiances of 200 or 80 μmol m–2 s–1, respectively (ecotypes Columbia and C24, nci = 6, nSD = 18). Diamonds indicate the ABA effect in cress plants (nci = 5, nSD = 48). All plants experienced an atmospheric CO2 concentration close to 390 μmol mol–1. (B) The changes in SD from (A) expressed as a percentage of control. The points sharing the same Ci co-ordinate in (A) and (B) represent identical treatments. Standard errors of the mean (bars), regression lines and 95 % confidence intervals are shown.

Comparison of the Ci response in cotyledons and true leaves of garden cress

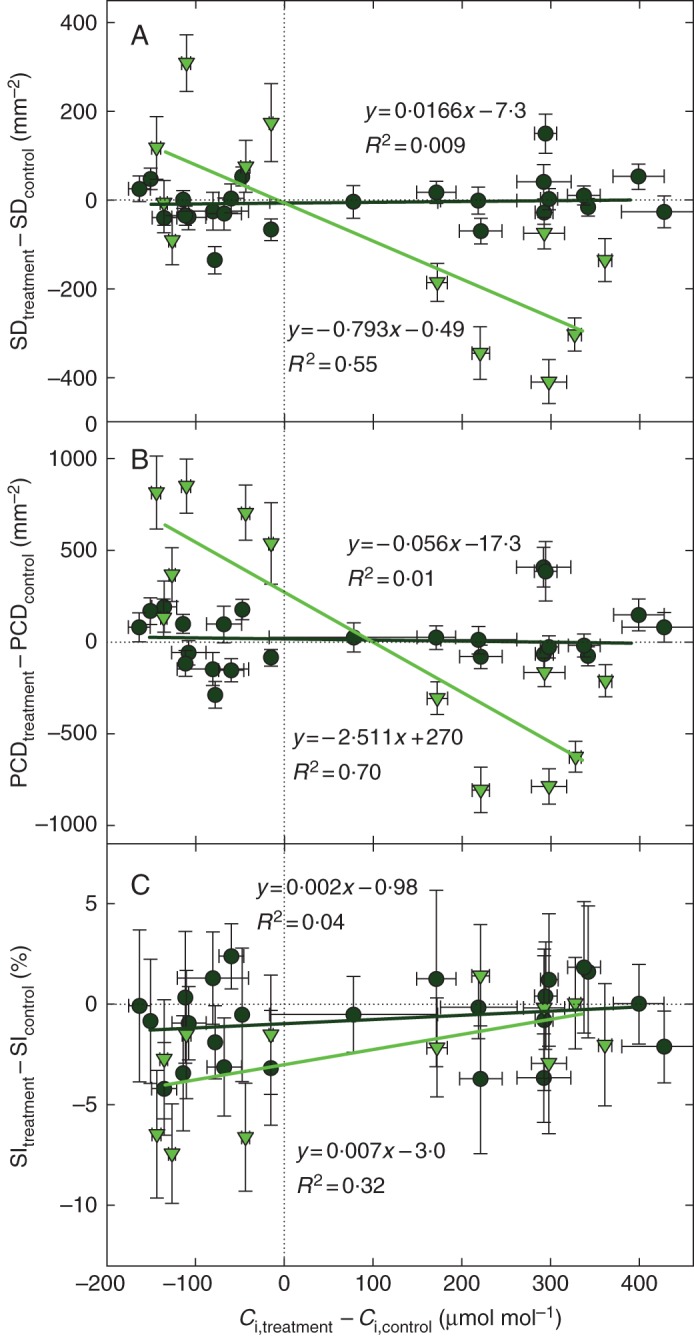

The results shown above were obtained at stable Ca. In controlled-atmosphere experiments with garden cress, we used ambient (400 μmol mol–1 as a control), sub-ambient (180 μmol mol–1) or super-ambient (800 μmol mol–1) CO2 concentrations to grow cress plants for 14 d (or 21 d for sub-ambient CO2) in air or in helox atmosphere, each with two different gas humidities and also under reduced total pressure. Variations in Ci were induced primarily by changing Ca, using helox instead of air [CO2 diffuses 2·3 times faster in helox than in air; see Parkhurst and Mott (1990)] and by reduction of total pressure, and only marginally by reduced air humidity. The time courses of developmental changes in δ and SD in all 18 experimental treatments are shown in Supplementary Data Figs. S1 and S2. The values in the bottom right quadrant of Fig. 2A and B (green triangles) show that the true leaves of super-ambient CO2 plants had fewer stomata and pavement cells than the control plants. Conversely, in sub-ambient CO2 plants, the SD and PCD increased (upper left quadrants of the plots). This effect was common for plants grown in air and helox, for plants grown at reduced atmospheric pressure (RP) and for both humidities (HH and LH). Therefore, for the regression analyses we analysed the six treatments (HH, LH and RP, each in helox and air) together and compared the Ci response of true leaves (in 14-day-old plants) and cotyledons (at 7 and 14 DAW). In contrast to the true leaves, cotyledons did not alter the SD and PCD in response to Ci. The slopes of the regression lines approached zero in cotyledons, while in the first leaves they significantly deviated from zero (Fig. 2; Table 2). The pavement cells in true leaves changed their density at 3·2 times the rate of stomata (see the ratio of slopes of the respective regression lines in Fig. 2A, B), which translates to an average reduction of 3·2 pavement cells for each stoma less in response to increasing Ci.

Fig. 2.

Changes in internal CO2 concentration (Ci) of the leaf in Lepidium sativum plants grown under sub-ambient or super-ambient CO2 concentrations, as related to changes in stomatal density (SD; A), pavement cell density (PCD; B) and stomatal index (SI; C). The negative values of the Ci difference show by how much Ci was lowered when Ca was reduced from 400 to 180 μmol mol–1; the positive values indicate the increase of Ci in plants grown at 800 compared with controls kept at 400 μmol mol–1. Stomatal and pavement cell density in the first leaves (light green triangles and light green regression line) was much more sensitive to CO2 concentration than in cotyledons (dark green circles and dark green regression line). Each point represents a difference between the Ca treatment (180 or 800) and Ca control (400) for one of three sub-treatments (two air humidities and hypobaric plants), each grown either in air or in helox gas mixture. Data for 14-day-old leaves and 7- and 14-day-old cotyledons are shown. The SD and Ci values used in calculation of the differences were means from three independent measurements (three plants per treatment). The Ci values were calculated from δ13C in plant dry matter (see Appendix). Bars show the standard error of the mean, for SI calculated from the primary SD and PCD data [see eqn (6) in ‘Statistical evaluation, meta-analysis’].

Table 2.

Comparison of density (number per unit area of leaf) and relative abundance of epidermal cells in cotyledons and the first leaves of garden cress and response of epidermal cell density to variations in the internal CO2 concentration of the leaf (Ci)

| Age (DAW) | Cotyledons |

First leaves |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD (mm–2) | PCD (mm–2) | SI (%) | SD (mm–2) | PCD (mm–2) | SI (%) | |

| 7 | 439 (25) | 1308 (70) | 25·2 (1·4) | |||

| 14 | 186 (11) | 535 (30) | 25·8 (2·4) | 535 (84) | 1304 (223) | 29·4 (2·0) |

| Slope of Ci response (mol μmol–1 mm–2 or % mol μmol–1 where marked *), (R2) | 0·017 (0·009) | –0·056 (0·011) | 0·0019* 0·0407) | –0·793 (0·549) | –2·511 (0·703) | 0·0069* (0·317) |

Density of stomata (SD) and pavement cells (PCD) per mm2 of projected leaf area (sum of adaxial and abaxial values) and stomatal index (SI) in cotyledons 7 and 14 d after seed watering (DAW) and in the first leaves 14 DAW are given.

Means and standard error of the means (in parentheses) are shown of sets obtained by pooling data from plants grown in three growth CO2 concentrations (180, 400 and 800 μmol mol–1), two air humidities (60 and 90 %), two different inert host gases (N2 and He) or reduced atmospheric pressure (n = 18, each n is a mean of three measurements on individual plants). Standard errors of SI means were calculated as means over all 18 treatments each obtained by the formula shown in the Materials and Methods.

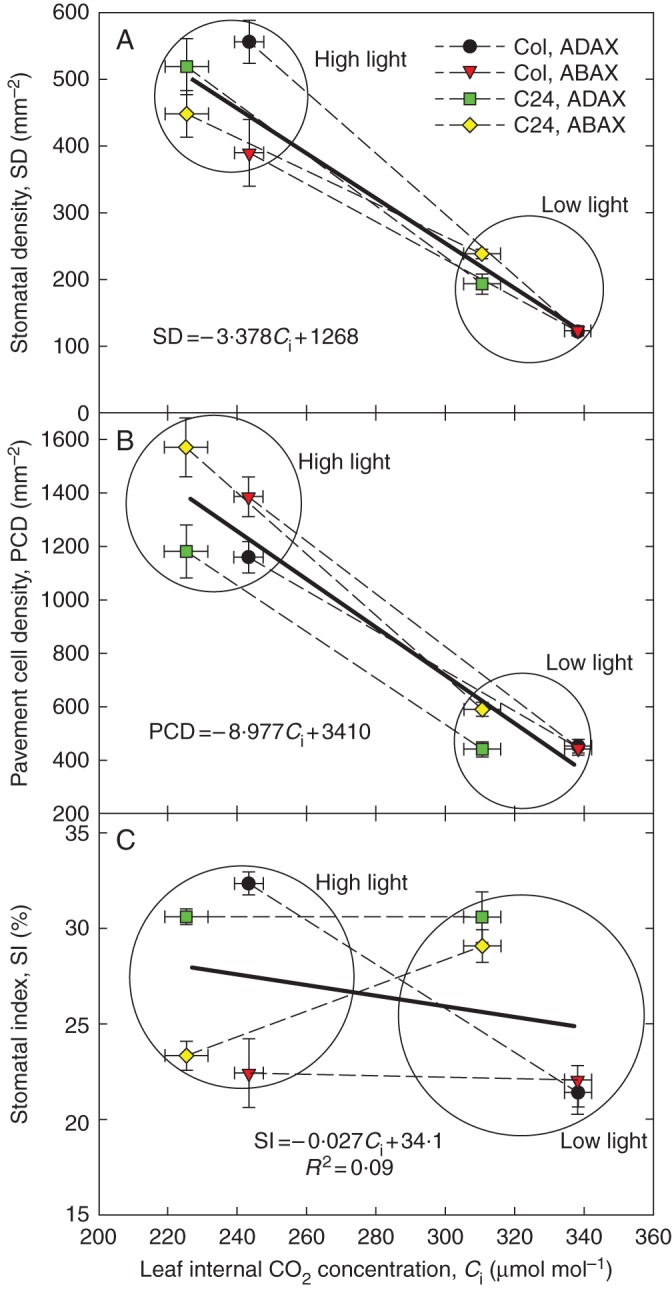

The fraction of stomata among all epidermal cells (the SI) was almost invariant over the whole investigated range of Ci in cotyledons and did not change during their development (SI ± SEM = 25·2 ± 1·4 % and 25·8 ± 2·4 % in 7- and 14-day-old plants, respectively). In true leaves, SI was higher than in cotyledons (29·4 ± 2·0 %) and changed only marginally with Ci (slope = 0·0069 % mol μmol–1, R2 = 0·32; see Table 2). However, standard errors of SI means determined from SD and PCD data were high and the SI changes with Ci non-significant (Fig. 2C). We obtained qualitatively similar Ci responses of SD and PCD in the experiment with arabidopsis true leaves grown at two different irradiances and equal Ca (expt 4, Fig. 3A, B). The SD and PCD increased with Ci reduction in strongly irradiated leaves. The response was similar for both leaf sides and both ecotypes. The SI did not respond to Ci in any systematic way and showed a slightly negative average slope (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Response to internal CO2 (Ci) of stomatal density (SD; A), pavement cell density (PCD; B) and stomatal index (SI; C) of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves grown at two irradiances. Two wild ecotypes, Columbia (Col) and C24, were grown under low light (25 μmol m–2 s–1) or high light (250 μmol m–2 s–1) conditions in growth chambers. Mean values of SD, PCD and SI (symbols) for the adaxial and abaxial sides of mature first rosette leaves are shown as well as the standard error of the mean (bars, nCi = 6 and nSD,PCD,SI = 16) and regression lines (thick solid line and equation) for information about leaf-averaged sensitivity (slope) of the relationship. The circles group the low and high light data.

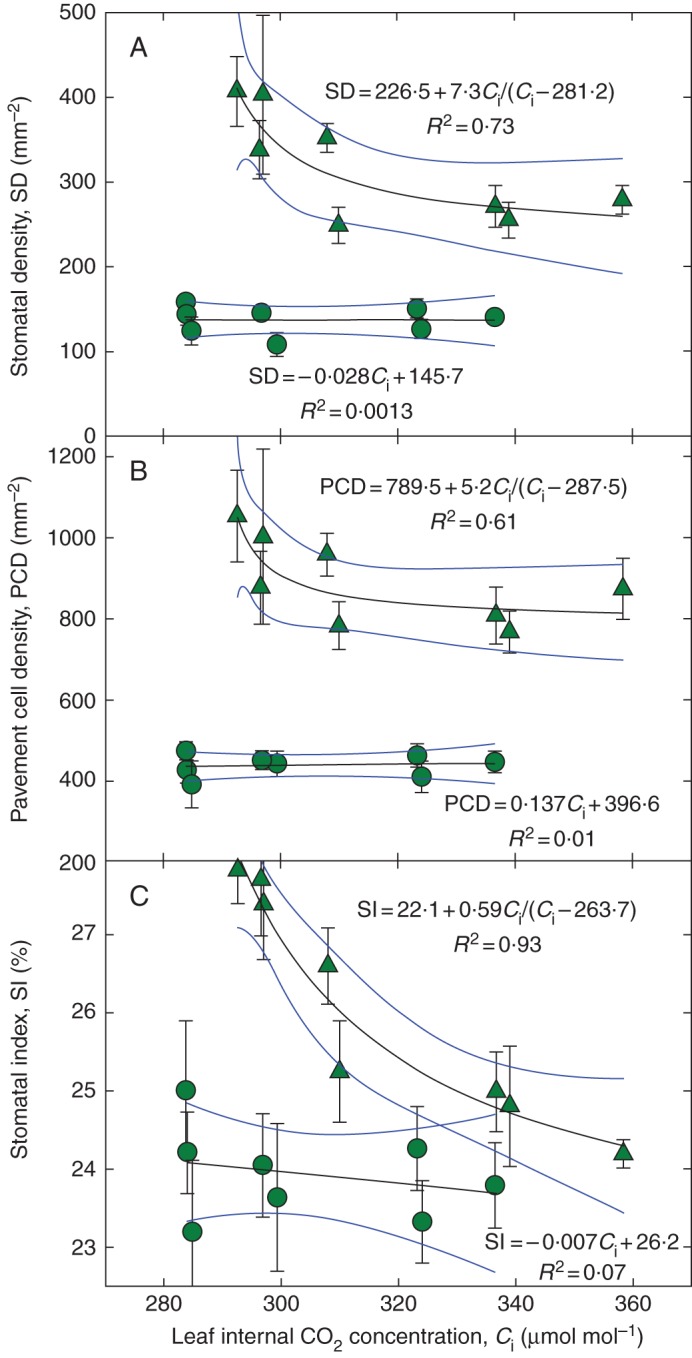

In order to verify the cotyledons' insensitivity to Ci in a way unbiased by estimation of the seed carbon fractions (see Appendix), we grew garden cress for a longer period (3 weeks) simultaneously under eight irradiances and equal Ca. The results confirmed that cotyledons are less sensitive to Ci than the first true leaves or are insensitive (Fig. 4A, B). The SD and PCD on the true leaves increased progressively at reduced Ci. The SI in cotyledons did not respond to Ci. However, in contrast to the previous experiment, SI significantly (P < 0·001) decreased with increasing Ci in true leaves (Fig. 4C). The same data as in Fig. 4 but plotted in the form of differences from the ‘control’ irradiance (310 μmol m–2 s–1) and shown separately for abaxial and adaxial leaf sides are presented in Supplementary Data Fig. S4. CO2 response of SI was steeper for the abaxial (lower) than the adaxial (upper) leaf side.

Fig. 4.

Response of stomatal density (SD; A), pavement cell density (PCD; B) and stomatal index (SI; C) of Lepidium sativum leaves and cotyledons to the internal CO2 (Ci) of leaves grown at various irradiances. The light green triangles and light green regression lines represent the first leaves; the dark green circles and dark green regression lines show the cotyledons' response. The plants were grown for 21 d under 7–8 photosynthetic photon flux densities (PPFDs), ranging from 100 to 590 μmol m–2 s–1, in 100 mL glass cuvettes ventilated with ambient air. The points represent averages from six independent runs of the experiment. Mean values and the standard error of the mean are indicated. Linear or hyperbolic fits with 95 % confidence intervals are shown.

DISCUSSION

In this study we demonstrate for the first time that the internal CO2 concentration of the leaf, Ci, correlates strongly with the development of stomatal and pavement cells expressed in terms of their densities. We applied several independent environmental factors to manipulate Ci. Therefore, the experimental results suggest, although they do not prove, that Ci or a Ci-related cue integrates the effects of those environmental parameters and conveys their signal into the machinery controlling SD. Our tests with cotyledons, the first assimilatory organs in a plant's life, support the previous evidence that adult leaves are essential in generating the signal (Lake et al., 2001, 2002 Miyazawa et al., 2006). The results show that photosynthesis- and stomata-controlled Ci correlates with the number of stomatal and epidermal cells per unit of leaf surface: both insufficient stomatal conductance gs and/or an enhanced photosynthetic rate reduce Ci, linking these processes directly or indirectly to the development of a new, acclimated leaf having more smaller stomata and pavement cells per mm2 of the leaf surface. Conversely, elevated Ci, caused for example by shading or elevated ambient CO2, correlates with fewer stomata and pavement cells per mm2 of the leaf surface and, consequently, larger epidermal cells develop (for examples of negative relationships between size and density of stomata, see Franks and Beerling, 2009; Franks et al., 2012). As this mechanism also operates at invariant Ca, our experiments suggest that the internal rather than ambient CO2 relates to the changes in SD and putatively exerts its feedback control over both the photosynthetic rate and stomatal conductance by modulating the SD and stomatal size, in analogy to the controls on stomatal aperture that were recognized long ago (Mott, 1988; Morison, 1998).

Lines of evidence for the involvement of a Ci-related factor in stomatal density signalling

We present several pieces of indirect evidence indicating the involvement of Ci or a Ci-linked stimulus in adjustment of SD. First, coefficients of determination indicating the apparent role of Ci in driving SD were fairly high (R2 = 0·95 in our experiments with four different species and several environmental factors; 0·55 and 0·70 for stomata and pavement cells, respectively, in garden cress treated with sub- and super-ambient Ca and a number of environmental factors; 0·73 and 0·61 in garden cress grown at eight different PPFD (see Figs 1, 2 and 4). Secondly, when shifting the axes in such a way that the values of SD and Ci in controls are set to zero as was done in Figs 1 and 2, the points representing the different treatments fall near to each other on a line through the origin. This near [0,0] intercept, shown in Figs 1A, 2A and 5A, suggests to us a dominant role for the Ci-related factor and only relatively minor effects of other factors.

In our estimates, sun-exposed beech leaves showed a 13·7 % increase in SD per 1 ‰ of 13C enrichment, when compared with shaded leaves. Sunflower plants grown under high-light or low-light conditions yielded values of 13·2 (control), 16·3 (PEG-stressed) and 18·9 (ABA-fed) % (SD) ‰–1 (δ). A 1 ‰ difference in δ is equivalent to a change in Ci of about 17 and 15 μmol mol–1 in air and helox, respectively. Similar values of SD sensitivity to Ci (derived from δ) have been observed (though not analysed) by other authors for a wide spectrum of plants and growth conditions [e.g. leaves of Vigna sinensis (Sekiya and Yano, 2008); fossil cuticles of the Cretaceous conifer Frenelopsis (Aucour et al., 2008); and the complex environmental factors acting along altitudinal gradients (Körner et al., 1988)]. Another line of evidence linking Ci with frequency of stomata was obtained by analysing published data from experiments where SD and 13C discrimination in leaf dry matter (δ) were measured concomitantly. We searched for data on δ and SD from controlled, mostly mono-factorial experiments with dicotyledonous plants. Results from 17 studies summarized in Supplementary Data Table S1 show that the values of SD sensitivity to Ci range between +10 and +20 % (SD) ‰–1 (δ). In terms of Ci and at the present ambient CO2 concentration, SD typically increases by 1 % when Ci drops by 1 μmol mol–1, and vice versa. The differences in δ between treated and control plants, converted to differences in Ci and plotted against the respective differences in SD (Fig. 5), show a similar pattern to those presented in Fig. 1.

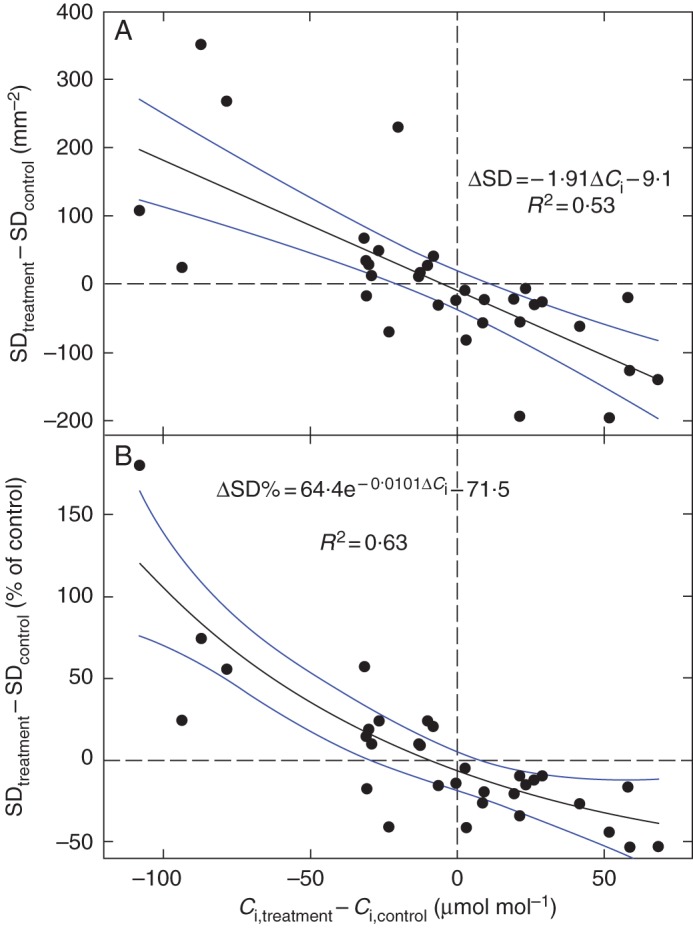

Fig. 5.

The effect of various environmental factors on concomitant changes in the internal CO2 concentration (Ci) and stomatal density (SD) of leaves. The Ci values were calculated from carbon isotope discrimination data extracted together with SD values from 17 publications presenting factorial experiments. The differences between treatment and control plants in SD values (A) and in SD normalized to SD of control (B) are shown together with the best fits and 95 % confidence intervals. The compiled data are shown in Supplementary Data Table S1, and come from the following studies: Bradford et al. (1983), Van de Water et al. (1994), Beerling (1997), Sun et al. (2003), Gitz et al. (2005), Takahashi and Mikami (2006), Aucour et al. (2008), He et al. (2008), Sekiya and Yano (2008), Lake et al. (2009), Yan et al. (2009), Craven et al. (2010), Gorsuch et al. (2010), He et al. (2012), Sun et al. (2012), Yan et al. (2012) and Rogiers and Clarke (2013).

SD response to factors other than Ci

Signalling in stomatal differentiation requires membrane-bound receptors, regulatory peptide ligands, a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase module and transcription factors with the respective genes expressed mostly in the epidermis, but also in the mesophyll (Casson and Gray, 2008; Shimada et al., 2011; Pillitteri and Torii, 2012). Co-ordinated and light-dependent development of stomata and chloroplasts is also mediated by brassinosteroids and other phytohormones (Wang et al., 2012). The complex signalling pathway leads to division of protodermal cells, with an increasing proportion of stomata among all epidermal cells (SI), and a rising number of stomata per unit of leaf area (SD) in the early phase of epidermal development. Later on in the phase of intensive leaf area enlargement, presumably all epidermal cells extend in size proportionally, keeping SI stable and reducing SD (Asl et al., 2011). Therefore, the final density and size of stomata on mature leaves is the result of interactions between genomic and environmental factors controlling the entry of cells into the stomatal lineage and their expansion. The idea that such a complex signalling pathway would respond exclusively to only one environmentally modulated factor such as Ci has to be treated with caution. Indeed, a direct response of stomatal development to the red light-activated form of phytochrome B and to blue light signals has recently been observed in arabidopsis (Boccalandro et al., 2009; Casson et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2009). These wavelength-specific light effects on SD often do not conform to the negative SD∼Ci relationship shown here. Thus, it seems that there could be two pathways in the light control of stomatal development: a photomorphogenesis-linked wavelength-specific mechanism and the Ci-mediated, probably CO2 assimilation-based, control. Due to their specific response to Ci, both pathways probably converge downstream of the putative Ci signalling point. Obviously, the SI sensitivity to Ci, shown in Fig. 4C for true leaves of garden cress, contradicts this scheme. The reasons are not clear and remain to be revealed. Perhaps true leaves of plantlets grown at low irradiances were not fully developed and had a higher proportion of pavement cells and lower SI than at high irradiance. Alternatively, another unknown factor apart from those controlled here affected the proportion of stomata especially on the abaxial leaf side (Supplementary Data Fig. S4C).

Is CO2 the underlying factor?

In this study, we show that SD correlates with Ci in true leaves. It does not necessarily mean that there is casual relationship between abundance or activity of CO2 molecules in the leaf interior and stomatal development. One aspect which must be considered is that the Ci values were inferred from discrimination against 13CO2, which takes place in the photosynthetically active leaf in light and is recorded in the leaf bulk dry mass (Farquhar et al., 1989). In addition, Ci estimated from13C is not a simple time average but the photosynthesis-weighted value of Ci averaged over the photoperiod (Farquhar, 1989). Thus, supposing that the Ci-related link to SD exists, we can expect that the putative factor modulating stomatal density and/or size is either photosynthesis-weighted Ci (CiP) or some CiP-linked intermediate averaged over the photoperiod. However, the daylight specificity of Ci as a signal in stomatal size and density remains to be confirmed. Data on the diurnal course of Ci during leaf development and SD in the developed leaf are rare. Recently, Rogiers and Clarke (2013) showed that elevated root-zone temperature increased mid-day and reduced nocturnal Ci (determined via gas exchange) in grapevine. Leaves that emerged during root-zone warming had a lower SD. These results support our finding that higher Ci leads to reduced frequency of stomata and that the daytime, not nocturnal, Ci is the controlling factor. Photorespiration is another powerful internal source of CO2 in light-exposed leaves which could also be used for testing the Ci effect on SD. Ramonell et al. (2001) showed that downregulation of the photorespiratory source of CO2 by the O2 content in ambient atmosphere being reduced to 2·5 %, and presumably a reduced Ci, increased both SD and starch content in newly developed leaves of arabidopsis. This indicates that CO2 or a CO2-derived cue rather than non-structural assimilates could affect SD and stomatal size.

Systemic vs. local signalling

Whole plants (or whole branches in the case of beech) were subject to fairly homogeneous environmental conditions in our experiments. Therefore, it is not possible to judge whether the CO2-derived signal was produced directly in the developing leaf or in a mature, lower insertion leaf and transmitted as a systemic signal (Lake et al., 2001, 2002; Coupe et al., 2006, and others). Our experiments in which we compared cotyledons and the first leaves of garden cress support this concept of systemic signalling. Despite the stomatal emergence extending through the period of advanced autotrophy, SD on mature cotyledons remained largely insensitive to Ci, Ca and light (Figs 2 and 4; Supplementary Data Fig. S4). Thus we suggest that, without a pre-existing carbon assimilation organ, the information on availability of CO2 or a CO2-related factor is not generated, cannot be conveyed to the developing cotyledons and cannot modulate the genetic programme of development of the stomata and epidermis. Nevertheless, cotyledons are probably competent in production of the systemic signal and transport to the true leaves at 7–9 DAW when they appear.

Conclusions

The SD and PCD of mature leaves co-vary with 13C discrimination caused by altering various environmental factors while keeping ambient CO2 stable. This translates into an inverse association between SD, PCD and the daytime-integrated internal CO2 concentration of the leaf. There is only a small (if any) change in the relative proportion of stomata to other epidermal cells (SI), with one exception, in a large number of experimental comparisons. Therefore, the results demonstrate overwhelmingly that the reduction in Ci hinders the expansion of leaf area, increases SD and reduces the size of stomata. In contrast, elevated Ci stimulates the expansion, increases the size of stomata and reduces SD. We suggest that the apparent Ci-dependent modulation of SD and PCD could translate the mesophyll demand for CO2 into a pattern of more numerous and smaller stomata on newly developed leaves. The putative Ci-sensing mechanism could integrate several environmental factors and relies on a signal transported from older, photosynthetically competent organs, including cotyledons in the case of the first true leaves. In contrast, the absence of older photosynthetic organs probably prevented the adjustment of the SD of cotyledons in response to Ci and environmental perturbations.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Ladislav Marek for carrying out the carbon isotope analyses, Petra Fialová and Marcela Cuhrová for technical assistance, Thomas Buckley, Ji-Ye Rhee and Gerhard Kerstiens for their valuable comments, Gerhard Kerstiens (Lancaster) also for language revisions, and Willi A. Brand and Graham D. Farquhar for their advice on CO2 fractionation due to diffusion in helium. The work is dedicated to Professor Lubomír Nátr, who recently passed away. The work was supported by the Grant Agency of the Czech Republic [project nos P501-12-1261, 14-12262S] and the Grant Agency of the University of South Bohemia [grant no. 143/2013/P]. Financial support by the DFG to L.S. is gratefully acknowledged.

APPENDIX

δ 13C-based determination of the internal CO2 concentration in mixotrophic tissues of leaves

Stomata develop at an early stage of leaf or cotyledon ontogeny. In L. sativum, it was possible to observe the first differentiated stomata on folded cotyledons as early as 48 h after seed soaking (data not shown). Cotyledons are almost entirely heterotrophic and built from seed carbon at that stage of development, which prevents the determination of internal CO2 concentration in the cotyledon from 13C abundance in its dry mass. A fraction f of the carbon forming the cotyledon is supplied from seed storage and keeps (with presumably minimum change) its 13C abundance (δs). The rest of the cotyledon's carbon, 1 – f, is assimilated by photosynthetic CO2 fixation and obeys the isotopic fractionation caused mainly by CO2 diffusion and Rubisco (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase) carboxylation, resulting in 13C depletion of newly formed triose phosphates expressed as δt. Only the latter part provides isotopic information on actual growth conditions and can be used for the calculation of Ci in developing cotyledons, provided f is available.The two-source carbon mixing model can be used to express the isotopic composition of the germinating plantlets δp:

| (A1) |

13C depletion of the newly formed triose phosphates against ambient air, Δt, depends on the ratio of the internal CO2 of the cotyledons and the external CO2 concentrations, Ci/Ca (Farquhar et al., 1989), as:

| (A2) |

where a and b denote fractionation factors due to diffusion in gas phase and carboxylation by Rubisco. Substitution for δt from eqn (A2) into eqn (A1) yields:

| (A3) |

under the condition that the seeds and atmosphere have the same δ values, δs ≅ δa, which is not unusual when compressed CO2 of fossil origin is used as a source for CO2 in the mixed atmosphere where the seeds germinate. In our case δa and δs were –28·19 and –28·13 ‰, respectively.

To calculate Ci from this equation, we have to know the fraction of seed carbon f. We derived this value using the time course of isotopic composition δp during the plantlets' early development from germination (f = 1 at DAW = 0) to the fully autotrophic stage (f = 0 at DAW = 14 in our conditions). The typical time course of δp had a sigmoid shape, approaching the most negative values between 14 and 21 DAW (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). The δp asymptote, δpl, estimated from sigmoid regression of the δp kinetics for true leaves, indicated the fully autotrophic stage. We re-scaled the δs – δpl values into the 1–0 range of f and calculated the fraction f in cotyledons of any particular age. The δp and f kinetics were specific for various Ca, indicating faster development at higher Ca concentrations (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). The kinetics also varied between plants grown in helox or air, with slightly higher slopes and faster development in helox. With f available, it was possible to calculate Ci in cotyledons and young true leaves as

| (A4) |

LITERATURE CITED

- Abrams MD. Genotypic and phenotypic variation as stress adaptations in temperate tree species – a review of several case-studies. Tree Physiology. 1994;14:833–842. doi: 10.1093/treephys/14.7-8-9.833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA, Rogers A. The response of photosynthesis and stomatal conductance to rising CO2: mechanisms and environmental interactions. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2007;30:258–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2007.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asl LK, Dhondt S, Boudolf V, et al. Model-based analysis of arabidopsis leaf epidermal cells reveals distinct division and expansion patterns for pavement and guard cells. Plant Physiology. 2011;156:2172–2183. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.181180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aucour AM, Gomez B, Sheppard SMF, Thevenard F. Delta C-13 and stomatal number variability in the Cretaceous conifer Frenelopsis. Palaeogeography Palaeoclimatology Palaeoecology. 2008;257:462–473. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker JC. Effects of humidity on stomatal density and its relation to leaf conductance. Scientia Horticulturae. 1991;48:205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ. Carbon isotope discrimination and stomatal responses of mature Pinus sylvestris L trees exposed in situ for three years to elevated CO2 and temperature. Acta Oecologica-International Journal of Ecology. 1997;18:697–712. [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Lomax BH, Royer DL, Upchurch GR, Kump LR. An atmospheric pCO(2) reconstruction across the Cretaceous–Tertiary boundary from leaf megafossils. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2002;99:7836–7840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122573099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerling DJ, Royer DL. Reading a CO2 signal from fossil stomata. New Phytologist. 2002;153:387–397. doi: 10.1046/j.0028-646X.2001.00335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann D. Stomatal development: from neighborly to global communication. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2006;9:478–483. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccalandro HE, Rugnone ML, Moreno JE, et al. Phytochrome B enhances photosynthesis at the expense of water-use efficiency in arabidopsis. Plant Physiology. 2009;150:1083–1092. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.135509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford KJ, Sharkey TD, Farquhar GD. Gas-exchange, stomatal behavior, and delta-C-13 values of the flacca tomato mutant in relation to abscisic acid. Plant Physiology. 1983;72:245–250. doi: 10.1104/pp.72.1.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson S, Gray JE. Influence of environmental factors on stomatal development. New Phytologist. 2008;178:9–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casson SA, Franklin KA, Gray JE, Grierson CS, Whitelam GC, Hetherington AM. Phytochrome B and PIF4 regulate stomatal development in response to light quantity. Current Biology. 2009;19:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coupe SA, Palmer BG, Lake JA, et al. Systemic signalling of environmental cues in Arabidopsis leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:329–341. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erj033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven D, Gulamhussein S, Berlyn GP. Physiological and anatomical responses of Acacia koa (Gray) seedlings to varying light and drought conditions. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2010;69:205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD. Models of integrated photosynthesis of cells and leaves. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 1989;323:357–367. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Richards RA. Isotopic composition of plant carbon correlates with water-use efficiency of wheat genotypes. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 1984;11:539–552. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Oleary MH, Berry JA. On the relationship between carbon isotope discrimination and the intercellular carbon dioxide concentration in leaves. Australian Journal of Plant Physiology. 1982;9:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Ehleringer JR, Hubick KT. Carbon isotope discrimination and photosynthesis. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1989;40:503–537. [Google Scholar]

- Figueroa JA, Cabrera HM, Queirolo C, Hinojosa LF. Variability of water relations and photosynthesis in Eucryphia cordifolia Cav. (Cunoniaceae) over the range of its latitudinal and altitudinal distribution in Chile. Tree Physiology. 2010;30:574–585. doi: 10.1093/treephys/tpq016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Beerling DJ. Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2009;106:10343–10347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904209106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks PJ, Leitch IJ, Ruszala EM, Hetherington AM, Beerling DJ. Physiological framework for adaptation of stomata to CO2 from glacial to future concentrations. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2012;367:537–546. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser LH, Greenall A, Carlyle C, Turkington R, Friedman CR. Adaptive phenotypic plasticity of Pseudoroegneria spicata: response of stomatal density, leaf area and biomass to changes in water supply and increased temperature. Annals of Botany. 2009;103:769–775. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcn252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitz DC, Liu-Gitz L, Britz SJ, Sullivan JH. Ultraviolet-B effects on stomatal density, water-use efficiency, and stable carbon isotope discrimination in four glasshouse-grown soybean (Glyicine max) cultivars. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2005;53:343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch PA, Pandey S, Atkin OK. Temporal heterogeneity of cold acclimation phenotypes in Arabidopsis leaves. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2010;33:244–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray JE, Holroyd GH, van der Lee FM, et al. The HIC signalling pathway links CO2 perception to stomatal development. Nature. 2000;408:713–716. doi: 10.1038/35047071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He CX, Li JY, Zhou P, Guo M, Zheng QS. Changes of leaf morphological, anatomical structure and carbon isotope ratio with the height of the Wangtian tree (Parashorea chinensis) in Xishuangbanna, China. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2008;50:168–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2007.00620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Liu G, Yang H. Water use efficiency by alfalfa: mechanisms involving anti-oxidation and osmotic adjustment under drought. Russian Journal of Plant Physiology. 2012;59:348–355. [Google Scholar]

- Hetherington AM, Woodward FI. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature. 2003;424:901–908. doi: 10.1038/nature01843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HH, Boisson-Dernier A, Israelsson-Nordstrom M, et al. Carbonic anhydrases are upstream regulators of CO2-controlled stomatal movements in guard cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12:87–93. doi: 10.1038/ncb2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang C-Y, Lian H-L, Wang F-F, Huang J-R, Yang H-Q. Cryptochromes, phytochromes, and COP1 regulate light-controlled stomatal development in arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2009;21:2624–2641. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.069765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Körner C, Farquhar GD, Roksandic Z. A global survey of carbon isotope discrimination in plants from high-altitude. Oecologia. 1988;74:623–632. doi: 10.1007/BF00380063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Woodward FI. Response of stomatal numbers to CO2 and humidity: control by transpiration rate and abscisic acid. New Phytologist. 2008;179:397–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Quick WP, Beerling DJ, Woodward FI. Plant development. Signals from mature to new leaves. Nature. 2001;411:154–154. doi: 10.1038/35075660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Woodward FI, Quick WP. Long-distance CO2 signalling in plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2002;53:183–193. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/53.367.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lake JA, Field KJ, Davey MP, Beerling DJ, Lomax BH. Metabolomic and physiological responses reveal multi-phasic acclimation of Arabidopsis thaliana to chronic UV radiation. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:1377–1389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa SI, Livingston NJ, Turpin DH. Stomatal development in new leaves is related to the stomatal conductance of mature leaves in poplar. Populus trichocarpa × P. deltoides). Journal of Experimental Botany. 2006;57:373–380. doi: 10.1093/jxb/eri278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morison JIL. Stomatal response to increased CO2 concentration. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1998;49:443–452. [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA. Do stomata respond to CO2 concentrations other than intercellular? Plant Physiology. 1988;86:200–203. doi: 10.1104/pp.86.1.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mott KA. Opinion: stomatal responses to light and CO2 depend on the mesophyll. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2009;32:1479–1486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadeau JA, Sack FD. Stomatal development: cross talk puts mouths in place. Trends in Plant Science. 2003;8:294–299. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00102-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantin F, Simonneau T, Muller B. Coming of leaf age: control of growth by hydraulics and metabolics during leaf ontogeny. New Phytologist. 2012;196:349–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst DF, Mott KA. Intercellular diffusion limits to CO2 uptake in leaves. Plant Physiology. 1990;94:1024–1032. doi: 10.1104/pp.94.3.1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillitteri LJ, Torii KU. Mechanisms of stomatal development. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 2012;63:591–614. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramonell KM, Kuang A, Porterfield DM, et al. Influence of atmospheric oxygen on leaf structure and starch deposition in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant, Cell and Environment. 2001;24:419–428. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retallack GJ. A 300-million-year record of atmospheric carbon dioxide from fossil plant cuticles. Nature. 2001;411:287–290. doi: 10.1038/35077041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogiers SY, Clarke SJ. Nocturnal and daytime stomatal conductance respond to root-zone temperature in ‘Shiraz’ grapevines. Annals of Botany. 2013;111:433–444. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcs298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL. Stomatal density and stomatal index as indicators of paleoatmospheric CO2 concentration. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology. 2001;114:1–28. doi: 10.1016/s0034-6667(00)00074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer DL, Wing SL, Beerling DJ, et al. Paleobotanical evidence for near present-day levels of atmospheric CO2 during part of the tertiary. Science. 2001;292:2310–2313. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5525.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoch PG, Zinsou C, Sibi M. Dependence of the stomatal index on environmental factors during stomatal differentiation in leaves of Vigna sinensis L. 1. Effect of light intensity. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1980;31:1211–1216. [Google Scholar]

- Sekiya N, Yano K. Stomatal density of cowpea correlates with carbon isotope discrimination in different phosphorus, water and CO2 environments. New Phytologist. 2008;179:799–807. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Sugano SS, Hara-Nishimura I. Positive and negative peptide signals control stomatal density. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2011;68:2081–2088. doi: 10.1007/s00018-011-0685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BN, Dilcher DL, Beerling DJ, Zhang CJ, Yan DF, Kowalski E. Variation in Ginkgo biloba L. leaf characters across a climatic gradient in China. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 2003;100:7141–7146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1232419100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun BN, Ding ST, Wu JY, Dong C, Xe SP, Lin ZC. Carbon isotope and stomata! Data of Late Pliocene Betulaceae leaves from SW China: implications for palaeoatmospheric CO2-levels. Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences. 2012;21:237–250. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Mikami Y. Effects of canopy cover and seasonal reduction in rainfall on leaf phenology and leaf traits of the fern Oleandra pistillaris in a tropical montane forest, Indonesia. Journal of Tropical Ecology. 2006;22:599–604. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas PW, Woodward FI, Quick WP. Systemic irradiance signalling in tobacco. New Phytologist. 2004;161:193–198. [Google Scholar]

- Tichá I. Photosynthetic characteristics during ontogenesis of leaves. 7. Stomata density and sizes. Photosynthetica. 1982;16:375–471. [Google Scholar]

- Van de water PK, Leavitt SW, Betancourt JL. Trends in stomatal density and C-13/C-12 ratios of Pinus flexilis needles during last glacial–interglacial cycle. Science. 1994;264:239–243. doi: 10.1126/science.264.5156.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Chen X, Xiang CB. Stomatal density and bio-water saving. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology. 2007;49:1435–1444. [Google Scholar]

- Wang ZY, Bai MY, Oh E, Zhu JY. Brassinosteroid signaling network and regulation of photomorphogenesis. Annual Review of Genetics. 2012;46:701–724. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willmer CM. Stomatal sensing of the environment. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society. 1988;34:205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI. Stomatal numbers are sensitive to increases in CO2 from preindustrial levels. Nature. 1987;327:617–618. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward FI, Bazzaz FA. The responses of stomatal density to CO2 partial pressure. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1988;39:1771–1781. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Z, Zhou G. Responses of leaf stomatal density to water status and its relationship with photosynthesis in a grass. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2008;59:3317–3325. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan DF, Sun BN, Xie SP, Li XC, Wen WW. Response to paleoatmospheric CO2 concentration of Solenites vimineus (Phillips) Harris (Ginkgophyta) from the Middle Jurassic of the Yaojie Basin, Gansu Province, China. Science in China Series D - Earth Sciences. 2009;52:2029–2039. [Google Scholar]

- Yan F, Sun YQ, Song FB, Liu FL. Differential responses of stomatal morphology to partial root-zone drying and deficit irrigation in potato leaves under varied nitrogen rates. Scientia Horticulturae. 2012;145:76–83. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.