Abstract

Introduction

Head and neck cancer is a debilitating and disfiguring disease. Although numerous treatment options exist, an array of debilitating side effects accompany them, causing physiological and social problems. Distraction osteogenesis (DO) can avoid many of the pathologies of current reconstructive strategies; however, due to the deleterious effects of radiation on bone vascularity, DO is generally ineffective. This makes investigating the effects of radiation on neovasculature during DO and creating quantifiable metrics to gauge the success of future therapies vital. The purpose of this study was to develop a novel isogenic rat model of impaired vasculogenesis of the regenerate mandible in order to determine quantifiable metrics of vascular injury and associated damage.

Methods

Male Lewis Rats were divided into two groups: DO only (n=5) AND Radiation Therapy (XRT) + DO (n=7). Afterwards, a distraction device was surgically implanted into the mandible. Finally, they were distracted a total of 5.1mm. Animals were perfused with a radiopaque casting agent concomitant with euthanasia, and subsequently demineralization, microcomputed tomography, and vascular analysis were performed.

Results

Vessel Volume Fraction, Vessel Thickness, Vessel Number, and Degree of Anisotropy were diminished by radiation. Vessel Separation was increased by radiation.

Conclusion

The DO group experienced vigorous vessel formation during distraction and neovascularization with a clear, directional progression, while the XRT/DO group saw weak vessel formation during distraction and neovascularization. Further studies are warranted to more deeply examine the impairments in osteogenic mechanotransductive pathways following radiation in the murine mandible. This isogenic model provides quantifiable metrics for future studies requiring a controlled approach to immunogenicity.

Keywords: head and neck cancer, distraction osteogenesis, tissue engineering, vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, radiation therapy, mechanotransduction, isogenic

Introduction

In 2013, an estimated 53,640 Americans will be affected by head and neck cancer. Comprising 3%-5% of all cancers in the United States, an estimated 11,520 will be fatal. [1] Treatment options for most head and neck cancers vary depending on the stage of the cancer and location of the primary tumor, but can include a combination of chemotherapy, surgery and adjuvant radiation therapy. Radiation is used to treat more than half of all cancer patients. [1] While clearly in wide use, the side effects of this treatment can cause an extensive array of debilitating sequelae for patients, particularly those later in need of reconstructive surgery.

In head and neck cancer treatment specifically, patients who receive radiotherapy may experience decreased mobility of the jaw, swelling, pain, or bony exposure of the mandible or maxilla. [2] Moreover, many patients have bone defects as a result of oncological resection and segmental mandibulectomy [3, 4]. Perhaps the most devastating of all possible side effects of radiotherapy is osteradionecrosis, a condition that includes exposed, devitalized bone through damaged surrounding mucosa. [5] Pathologic fracture, another associated morbidity, can often be difficult to treat, affecting the quality of daily life for patients. Reduced vascularity in the bone accompanies the aformentioned consequences of adjuvant radiation therapy. This devascularization impedes the vigor of bone cells and hampers the likelihood of successful wound healing. [6]

Most clinical treatment practice dictates that bone defects and associated complications of poor bone healing secondary to irradiation are reconstructed utilizing rigid fixation in concert with free tissue transfer. Due to the deleterious consequences of radiation, however, these procedures have high failure rates and can generate additional devastating complications, such as regional or distal donor site morbidity. Distraction osteogenesis (DO) is a reliable treatment approach for reconstruction of craniofacial anomalies, which avoids the issue of donor site morbidity, and furthermore simultaneously generates both bone and soft tissue. In DO, mechanotransduction at the fracture site stimulates a potent osteogenic and vasculogenic response in regenerate bone, creating anisotropically-oriented bone. [7, 8] While distraction osteogenesis exhibits hypervascular characteristics, radiation greatly inhibits this hypervascularity. Radiation interferes with normal endothelial cell function, causes damage to bone marrow, and induces vascular stiffening. [9] Vessel volume and vessel thickness in radiated, uninjured mandibular bone display significant diminution following radiation. [10] These anti-vasculogenic effects complicate wound healing and may, in part, inhibit the formation of targeted bony unions in distraction osteogenesis. In order to utilize distraction osteogenesis as a consistently viable treatment option for craniofacial reconstruction in radiotherapy patients, the detailed effects of radiation on neovasculature must be definitively quantified, specifically in an isogenic model, in order to develop quantifiable metrics to gauge the success of future therapies.

A number of treatment stratagems are currently being popularized in the long bone and elsewhere which make an isogenic model highly desirable [11, 12]. An isogenic model allows for the easy harvest and free transfer of cells and tissues between animals, allowing bone grafts and cell-based therapies to be assayed without the fear of immunogenic issues. While this is also true for a xenograft/athymic model as well, those animals have a much higher risk of operative infection [13], as well as altered inflammatory cytokine production and expression [14-16], which can play a central role in osteogenesis [17]. Although this is possible with autologous tissues in outbred strains, harvest volumes and yields can make this an impractical option. As such, isogenic models allow for relative immune-competency while simultaneously allowing for implantation of non-autologous tissues.

Here we investigate the effects of radiation on neovasculature during distraction osteogenesis in the isogenic murine mandible. It is known that radiotherapy can play a significant role in impairing the healing mechanisms in regenerate bone. [18, 12, 19, 20] Therefore, the purpose of this study was to specifically develop a novel isogenic rat model of impaired vasculogenesis of the regenerate mandible in order to determine quantifiable metrics of vascular injury and associated damage. Once the specific level and extent of injury is ascertained, cell based therapies can be utilized to remediate and assuage the damage, restore the ability to heal bone, and permit the utilization of Distraction Osteogenesis in this challenging patient population. We also investigated the effects on the degree of anisotropy of the neovasculature due to radiation, thereby providing critical information about the effect of radiation on the vascular mechanical response central to bone regeneration in distraction osteogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Lewis Rats, 400 g, were obtained through the University of Michigan's Unit Laboratory Animal Medicine (ULAM) department in compliance with their subdivision of the University of Michigan's University Committee on Use and Care of Animals (UCUCA). Rats were weighed and provided water bottles and regular chow ad libitum upon arrival to the laboratory. They were acclimated for 7 days before radiation. Animals were randomly assigned to 2 groups. (1) DO (distraction osteogenesis only, n=5), (2) XRT/DO (radiation therapy + distraction osteogenesis, n=7).

Radiation

Rat hemi-mandibles were irradiated using a Philips RT250 orthovoltage unit (250 kV, 15 mA) (Kimtron Medical), fractionating the dose at 3.72 Gy/min over 5 days, for a 35 Gray total, in the Irradiation Core at the University of Michigan Cancer Center. X-Rays were utilized since they taper off quickly, affecting only the one side of the mandible, thus obviating the need for any intraoral shield. They provided the same physiologic effect on bone and soft tissue as gamma radiation does. Rats were anesthetized using isoflurane/oxygen (2% and 1 L/min), and then placed right side down, so only the left hemi-mandible was irradiated. A lead shield with a rectangular window protected the pharynx, brain, and the remainder of the animal. Dosimetry was carried out using an ionization chamber connected to an electrometer system, which is directly traceable to a National Institute of Standards and Technology calibration. This radiation protocol has been performed for several years in the department of Radiation Oncology under ULAM/UCUCA-approved protocols. The rats were maintained on regular chow and water and observed for 2 weeks before surgery. The diet was changed to moist chow 48 h preoperatively along with Hill's high-calorie diet.

Perioperative preparation

Gentamycin, (30 mg/kg subcutaneously (SQ), as given prophylactically pre-op and once post-op. Rats were given Buprenorphine (0.15 mg/kg SQ) along with 15 cc/kg SQ lactated ringer's solution (LR), and then anesthetized using isoflurane/oxygen throughout the surgical procedure. Animals were placed supine on a warming blanket with a protective ocular lubricant and monitored with a pulse oximeter connected to an oxygen saturation monitor.

Surgical procedure

The surgical procedure was previously described and published [19]. After standard prepping and draping with the animal on its dorsum and the neck extended, a 2-cm midline incision was placed ventrally from the anterior submentum to the neck crease. Skin flaps were elevated and secured laterally, and then the anterior-lateral mandible was exposed avoiding the mental nerve. A horizontal through-and-through defect was drilled (1/32) to pass a 1.5″ #0–80 stainless steel threaded rod across with both ends brought externally through the skin, creating the anterior portion of the modified external fixator. Then, a 1-cm incision in the mid-portion of the masseter muscle, directly over the inferior border of the mandible exposed the angle of the mandible, which was dissected laterally and superiorly toward the sigmoid notch and coronoid process. A small defect was drilled 2 mm anterior-superior to the mandibular angle, bilaterally, to secure a #0–80 threaded pin secured with a titanium washer and nut, and then brought externally through the skin for the posterior fixator placement. The completed fixator was secured, and then a vertical osteotomy was created using a10-mm micro-reciprocating blade (Stryker) 2 mm anterior to the posterior washer on the left hemi-mandible, extending from the inferior margin of the mandible superiorly to the sigmoid notch along the anterior aspect of the coronoid process. The external fixator device was adjusted to insure reduction and hemostasis of the osteotomy edges. The wounds were irrigated, hemostasis verified, and then the incision was closed with staples.

Postoperative care

The animals were caged under the heat lamp and monitored with additional hydration via SQ LR, 15 cc/kg and observed for 1 h. Two doses of gentamycin were given Q12 h following surgery. Buprenorphine was continued (0.15–0.5 mg/kg) with 10 cc D5LR SQ Q12 h through post-op day (POD) #4 and as needed thereafter, along with moist chow, a high-calorie Hill's a/d diet and water ad libitum. Bactrim was given daily to prevent infection. Pin sites were cleaned with Novalsan BID, teeth clipped weekly, and staples removed by POD #14. All use and care was in compliance with UCUCA as well as the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals per our protocol #PRO00001267.

Distraction protocol

The distraction screw was half-turned corresponding to a 0.3 mm separation of the osteotomy fronts, beginning the pm of POD #4 and continued through the pm of POD #12. We performed a total of 17 half-turns, each on a Q12-h interval, for a total of 5.1 mm osteotomy distraction. Following DO, rats underwent 28 days of consolidation and were sacrificed on POD #40.

Tissue harvest

Animals were sacrificed on postoperative day 40 via an isoflurane overdose followed by thoracotomy. Mandibles were dissected out immediately following perfusion and euthanasia.

Perfusion Protocol

The perfusion protocol for this murine mandible model has been published previously. [21] Briefly, all rats were anesthetized before performing a thoracotomy and left cardioventricular catheterization. Perfusion with heparinized normal saline followed by pressure fixation with normal buffered formalin solution ensured euthanasia. After fixation, the vasculature was injected with Microfil (MV-122; Flow Tech, Carver, Mass). Mandibles were harvested and demineralized using Cal-Ex II (Fisher Scientifics, Fairlawn, NJ), a formic acid solution. Perfusion was verified by coloration of the dissected mandible and by subsequent micro-CT maximal intensity projection (MIP). Leeching of mineral was confirmed with serial radiographs to ensure adequate demineralization before scanning.

Imaging

Specimens were scanned at 18-Km voxel size with micro-CT. We previously used this voxel size and found it optimal to adequately resolve small, murine mandibular vessel networks. The region of interest (ROI) was defined as a distance measuring 5.1 mm after the third molar of the left hemi-mandible. At an 18-Km resolution, this is equivalent to 283 slices. Analysis of the ROI was then performed with MicroView 2.2 software (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI). Contours were defined, highlighting the ROIs using the spline function. Analysis of vascularity in this region is accomplished by setting a global grayscale threshold of 1000 HU to differentiate vessels from surrounding tissue, as previously described. [21] Using this information, MicroView allocates only the number of voxels above this threshold and uses stereologic algorithms to assign relative densities to the voxels based on the contrast content within the vessels. The MicroView's analysis of the ROI reported 5 metrics, all of which controlled for total size of the ROI: vessel volume fraction (VVF), vessel number (VN), vessel thickness (VT), vessel separation (VS), and degree of anisotropy (DA). VVF depicts the fraction of bone occupied by the volume of vessels within the ROI tissue. It is calculated based on the voxel size and the number of segmented voxels in the 3-D image after application of the binarization threshold. VN is a reflection of the actual number of vessels per millimeter within the ROI. To calculate VN, a segmented volume is skeletonized, leaving just the voxels above our binarization threshold at the midaxes of the vascular structures. The VN is defined as the inverse of the mean spacing between the midaxes of the structures in the segmented volume. VT is measured by calculating an average of the local voxel thicknesses within the vessel. Local voxel thickness is defined as the diameter of the largest sphere that both contains the point regardless of position within the sphere and is completely within the structure of interest. This distinguishes the blood vessel from the background space surrounding the object. [22] It is worth noting that VT, in this case, defines the intraluminal diameter of the vessel and not the thickness of the vessel wall. In addition, for qualitative comparison, 3-D visualization of vascular anatomy was accomplished using Maximal Intensity Projections (MIPs). This enables instant volume rendering of a volumetric data set, yielding a flattened 2-D representation of the scanned specimen. VS measures the distance between adjacent vessels in the ROI. It is calculated using the MicroView's stereology function. DA is a measure of the orientation of the trabecular architecture. It depicts the directionality of growth of new blood vessels. DA is calculated using the mean intercept length (MIL) method, which measures the intersections of a test grid with the trabecular structure and calculates the fabric ellipsoid, a 3-D ellipse. MicroView uses an algorithm to determine the length of the axes of the ellipsoid and their corresponding directions. DA is defined as the ratio of the length of the maximum and minimum axes.

Results

Maximal Intensity Projections

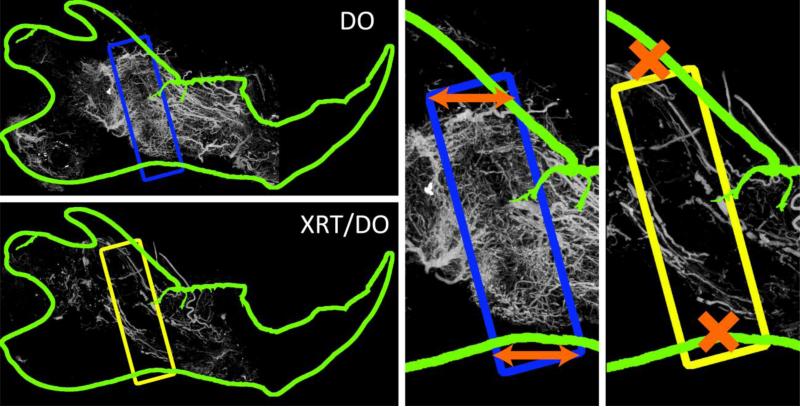

Examination of the maximal intensity projections (MIPs) in Figure 1 provides a clear distinction between neovasculature in the DO group and the XRT/DO group. The DO group clearly displayed dense, vigorous vessel formation in the distraction gap. This neoangiogenesis contrasted with the larger, thicker, and sparser vessels outside the region of interest. The neovasculature also exhibited a large degree of anisotropy across the axis of distraction and within the region of interest. In stark contrast to the DO group, the neovasculature of the XRT/DO group was weak and scarce. The new vessels also lacked any clear anisotropic response, implying damage to the mechanotransductive pathways that contribute to directionality of neovasculature.

Figure 1.

Maximal Intensity Projections (MIPs), with regions of interest (ROI) highlighted within the rectangle. TOP LEFT: DO mandible with ROI highlighted in blue. Note the smaller, denser, more robust neovasculature within the ROI as compared to the larger caliber vasculature outside the ROI. BOTTOM LEFT: XRT/DO mandible with ROI highlighted in yellow. Note the general diminishment of vascularity due to radiation therapy, particularly within the regenerate region. CENTER: DO ROI enlarged. Note the general horizontal orientation of the neovasculature, mirroring that of the axis of distraction, as indicated by the orange arrows.RIGHT: XRT/DO ROI enlarged. While the vascularity within the ROI was diminished, the vasculature that was present had a more isotropic orientation than the DO group.

Stereologic Metrics

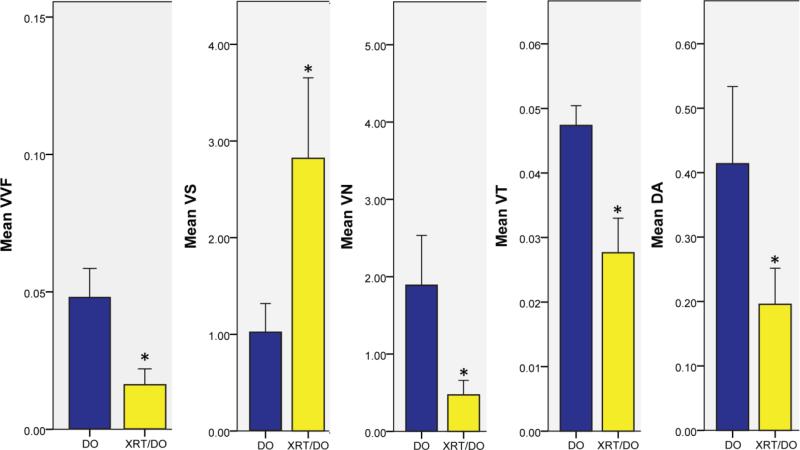

The drastically sparse vessel formation observed in the XRT/DO group in Figure 1 was quantitatively analyzed and compared via a series of stereologic metrics, as displayed in Figure 2. Neovasculature in the XRT/DO group exhibited vessel separation (VS), defined as the mean interaxial distance between two vessels, almost triple that of the neovasculature in the DO group (DO: 1.023 ± 0.30, XRT/DO: 2.820 ± 0.833, p = 0.003). Neovasculature in the XRT/DO group also had a smaller vessel number (VN), defined as the mean number of vessels that intersect an arbitrary 1mm line, than that of the DO group, demonstrating that the XRT/DO group had significantly diminished vessel formation (DO: 1.893 ± 0.641, XRT/DO: 0.471 ± 0.188, p = 0.022). Vessel volume fraction (VVF), defined as the fraction of the ROI comprised of vasculature, was also significantly lower in the XRT/DO group, suggesting a negative effect on perfusion of the surrounding tissue (DO: 0.048 ± 0.011, XRT/DO: 0.016 ± 0.006, p = 0.004). The XRT/DO group displayed a smaller vessel thickness (VT), defined as mean intraluminal diameter of each blood vessel (DO: 0.047 ± 0.003, XRT/DO: 0.027 ± 0.005, p = 0.023).

Figure 2.

Stereologic metrics for vessel volume fraction, (VVF - cc/cc), vessel separation, (VS - mm), vessel number, (VN – mm-1), vessel thickness, (VT - mm), and degree of anisotropy, (DA – 1- (length of shortest axis/length of longest axis)). * indicates p < 0.05. BLUE: DO group. YELLOW: XRT/DO group.

Another metric that was examined and quantified was the degree of anisotropy (DA). Defined as the quantification of the extent of directionality and orientation of the blood vessels, the degree of anisotropy in the XRT/DO group was significantly lower than the vasculature of the DO group (DO: 0.413 ± 0.120, XRT/DO: 0.196 ± 0.056, p = 0.004). The more randomized formation of blood vessels in the XRT/DO group suggests impairment of mechanotransductive response pathways innate to DO, as well as the associated mechano-response inherent in vessel formation in the regenerate, as a result of radiation.

Discussion

Distraction osteogenesis continues to be a reliable method for reconstruction of craniofacial anomalies, especially in pediatric populations. For head and neck cancer patients, however, distraction osteogenesis following radiotherapy does not yield consistently successful results. [10] In order to deepen the understanding of radiation damage to the hypervascular environment of distraction osteogenesis, further quantifiable metrics were warranted. Specifically, our experiments established metrics examining the vessel volume fraction, vessel number and thickness, and vessel separation, as well as metrics regarding the degree of anisotropy of neovasculature. By examining these metrics in an isogenic model, novel cell-based treatment regimens can be specifically designed to remediate these deficiencies, and precisely appraise the degree of their efficacy, thus potentially enabling the development of superior reconstructive regimens for head and neck cancer victims.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of radiation on the degree of vascular associated anisotropy in distraction osteogenesis, and moreover, the first to examine vascular stereologic metrics in an isogenic model of irradiated distraction osteogenesis. Such an isogenic model provides quantifiable metrics for future studies requiring a controlled approach to immunogenicity. Emerging literature has suggested that cell replacement therapies, such as mesenchymal stem cells implantation [23], can aid in bony healing in suboptimal conditions, such as in an irradiated field [12]. Isogenic model systems provide a number of advantages which make them attractive for assaying such therapies. They allow for the free transfer of cells and tissues between animals, allowing for specific animals to be designated for sacrifice or operation, lowering the infection risk and increasing experimental power, without the fear of rejection of tissues. While this is possible in athymic models as well, many have altered inflammatory cytokine expression profiles, such as fibroblast growth factor 2, transforming growth factor β, tumor necrosis factor α, and interferon γ, [24, 25] all of which are known to have significant effects on bone healing or osteogenesis [25, 24]. As such, an isogenic animal model offers an ideal compromise between immunocompetency, experimental ease, and fidelity of bone response.

Previous studies have shown that distraction osteogenesis is an intensely angiogenic event [26-28] whereby fracture strain upregulates VEGF and mobilizes epithelial progenitor cells (EPCs) from bone marrow to the distraction site, where they then actively participate in neovascularization [26]. Our study demonstrated that this response is well-preserved in an isogenic rat mandible. Figure 1 demonstrates the clear proliferation of vascularity in the distracted region as compared to the surrounding mandibular vasculature.

Studies have also shown that radiation can negatively impact the proliferation of vascularity following distraction osteogenesis in other models [10,29] Our results clearly display impairments in vasculogenesis, thus further validating previous outbred rat experiments. The XRT/DO group demonstrated a smaller vessel volume fraction when compared to the DO group, as well as an increased vessel separation. Increased vessel separation translates into a decrease in vascular density. [20] Taken together, these two stereologic metrics may suggest inadequate blood supply to surrounding tissues. Insufficient blood supply hampers the growth of viable bony regenerate in the distraction gap. By quantifying the decrease in vessel volume fraction and the increase in vessel separation in the XRT/DO group, further studies can focus on remediating these specific effects to determine their palliative effects on bone healing.

The stereologic metric for vessel thickness demonstrated a decrease in the XRT/DO vasculature. This decrease in vessel thickness, when compared to the DO group, represented a shrinking of the vessel lumen. Radiation may cause the new vessels to form thick walls and cause the lumen to be significantly smaller than neovasculature formed in the absence of radiation. We posit that the reduced size of the lumen in the regenerated vasculature is associated with a decrease in perfusion. This decrease in perfusion causes regional hypoxia in the surrounding tissues, and inhibits sufficient oxygen supply hindering successful bony healing. Collectively, the stereologic metrics unmistakably describe the negative consequences of radiation on the neovasculature of regenerate bone. The metrics display the possibility of weak, unfavorable regenerate formation hindering the possibility of proper healing.

The degree of anisotropy was also quantified. The distraction process, through a mechanotransductive response to physical stsrain, is known to produce directionally-oriented bone via the integrin-mediated, extracellular signal-related kinase (ERK) 1/2 dependent pathway [30], the cellular-Src dependent mechanotransduction pathway [31], and the bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) pathway[32]. These pathways have a high level of cross-talk with one another and with many other signaling pathways [33]. This bone anisotropy is reflected in the vascularity of the regenerate region in long bones [8]. In Figure 1, a clear directionality is evident in the vasculature of the DO group. The rat mandibles underwent distraction along their transverse plane. The regenerate vasculature mirrors this orientation, as demonstrated by the orange arrow in Figure 1. Thus, distraction osteogenesis provokes a strong anisotropic response, linking the mechanical strain to vascular growth and implying elements of an associated mechanotransductive pathway. We have demonstrated, however, that the XRT/DO group lacks the anisotropic response observed in the DO group. The vasculature reveals a more randomized formation, with no clear depiction of directional movement across the axis of distraction, implying damage or compromise of the mechanotransductive pathways responsible for the DO effect. There is evidence that suggests radiation affects the ERK 1/2 pathway (in neuroblastoma cells), which may in part explain the randomized vessel formation [34]. Radiation also causes a down-regulation of the BMP-2/BMP receptor complex, therefore reducing the activity of the BMP-2 pathway [35]. The Smad pathway is also affected by radiation through a reduction in phosphorylation of Smad proteins [36]. Sakurai et al. showed that yet another pathway, the Runx2 pathway, is also affected by radiation.[37] Following exposure to radiation, Runx2 mRNA levels decreased.[35] Interferences with the proper function and communication of these specific pathways may well contribute to the diminished vessel formation in the XRT/DO group. Future studies are necessary to elucidate the exact mechanism by which radiation impairs the anisotropic DO effect, such that targeted therapies can be developed to improve these outcomes.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effect of radiation on the degree of vascular associated anisotropy in distraction osteogenesis, and moreover, the first to examine vascular stereologic metrics in an isogenic model of irradiated distraction osteogenesis. The DO group displayed vigorous vessel formation during distraction, while the XRT/DO group displayed overwhelmingly weak, sparse vessel formation. The DO group displayed neovascularization with a clear, directional progression across an axis of distraction which was absent in the XRT/DO group neovasculature. Further studies are warranted to more deeply examine the impairments in osteogenic mechanotransductive pathways following radiation in the murine mandible. This isogenic model provides quantifiable metrics for future studies requiring a controlled approach to immunogenicity such as studies involving cell-based therapies. The hope is that such therapies can more directly remediate the negative impacts of radiation and make distraction osteogenesis a consistently successful reconstructive option for head and neck cancer patients who have received radiotherapy.

Highlights.

Determined quantitative metrics of isogenic murine mandibular vascular regenerate.

Radiation impairs microvascular metrics of endogenous bony tissue regeneration.

Radiation disrupts the vascular mechanotransduction in distraction ostoegenesis.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Funding was provided by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 CA 12587-01 to Steven R Buchman, M.D. and NIH-T32 GM 008616 to C. L Marcelo.

Abbreviations

- DA

Degree of anisotropy

- DO

Distraction osteogenesis

- HIF

Hypoxia inducible factors

- MIL

Mean intercept length

- MIP

Maximal Intensity Projection

- POD

Post-operative day

- ROI

Region of interest

- VN

Vessel number

- VS

Vessel separation

- VT

Vessel thickness

- VVF

Vessel volume fraction

- XRT

X-Ray Radiation Therapy

- XRT/DO

Radiation and distraction osteogenesis

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society . Cancer Facts & Figures. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2. [April 28, 2013];Osteoradionecrosis. www.oralcancerfoundation.org, from http://www.oralcancerfoundation.org/treatment/osteoradionecrosis.html.

- 3.Meazzini MC, Mazzoleni F, Bozzetti A, Brusati R. Comparison of mandibular vertical growth in hemifacial microsomia patients treated with early distraction or not treated: Follow up till the completion of growth. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial Surgery. 2012;40(2):105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang Z, Niu F, Tang X, Yu B, Liu J, Gui L. Staged reconstruction for adult complete Treacher Collins syndrome. J Craniofacial Surg. 2009;50(5):1433–8. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181af21f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marx RE,DDS. Osteoradionecrosis: a new concept of its pathophysiology. Oral Maxillofacial Surgery. 1983:283–288. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(83)90294-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Würzler KK, MD, DMD, DeWeese TL, MD, Sebald W, PhD, Reddi AH., PhD Radiation-induced impairment of bone healing can be overcome by recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 1998;9(2):132–137. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199803000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tong L, Buchman SR, Ignelzi MA, Rhee S, Goldstein SA. Focal Adhesion Kinase Expression during Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis: Evidence for Mechanotransduction. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2003;111(1):211–222. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000033180.01581.9A. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.PRS.0000033180.01581.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Richards M, Goulet JA, Schaffler MB, Goldstein SA. Temporal and Spatial Characterization of Regenerate Bone in the Lengthened Rabbit Tibia. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1999;14(11):1978–1986. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1978. http://dx.doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.11.1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Soucy KG, Attarzadeh DO, Ramachandran R, Soucy PA, Romer LH, Shoukas AA, Berkowitz DE. Single exposure to radiation produces early anti-angiogenic effects in mouse aorta. Original Paper. doi: 10.1007/s00411-010-0287-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inyang AF, Schwarz DA, Jamali AM, Buchman SR. Quantitative histomorphometric assessment of regenerate cellularity and bone quality in mandibular distraction osteogenesis after radiation therapy. Journal of Craniofacial Surgery. 2010;21:1438–1442. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ec693f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Levi B, Nelson ER, Brown K, et al. Differences in Osteogenic Differentiation of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells from Murine, Canine, and Human Sources In Vitro and In Vivo. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;128(2):373–386. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31821e6e49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande S, et al. Stem Cell Therapy Remediates Reconstruction of the Craniofacial Skeleton after Radiation Therapy. Stem Cells and Development. 2013;22(11):1625–1632. doi: 10.1089/scd.2012.0472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rolstad B. The athymic nude rat: an animal experimental model to reveal novel aspects of innate immune responses? Immunological Reviews. 2001;184(1):136–144. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2001.1840113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grabbe S, Gallo RL, Lindgren A, Granstein RD. Deficient antigen presentation by Langerhans cells from athymic (nu/nu) mice. Restoration with thymic transplantation or administration of cytokines. J Immunol. 1993;151(7):3430–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao UR, Vickery AC, Kwa BH, Nayar JK. Regulatory cytokines in the lymphatic pathology of athymic mice infected with Brugia malayi. International Journal for Parasitology. 1996;26(5):561–565. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(96)00036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shibahara T, Kokuho T, Eto M, et al. Pathological and Immunological Findings of Athymic Nude and Congenic Wild Type BALB/c Mice Experimentally Infected with Neospora caninum. Veterinary Pathology. 1999;36(4):321–7. doi: 10.1354/vp.36-4-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenfield EM, Bi Y, Miyauchi A. Regulation of osteoclast activity. Life Sciences. 1999;65(11):1087–1102. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(99)00156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang SY, Deshpande SS, Donneys A, Rodriguez JJ, Nelson NS, Felice PA, Buchman SR. Parathyroid hormone reverses radiation induced hypovascularity in a murine model of distraction osteogenesis. Bone. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2013.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farberg AS, et al. Deferoxamine reverses radiation induced hypovascularity during bone regeneration and repair in the murine mandible. Bone. 2012;50:1184–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tchanque-Fossou CN. Amifostine Remediates the Degenerative Effects of Radiation on the Mineralization Capacity of the Murine Mandible. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2012;129(4):646e–655e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182454352. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182454352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jing X, Farberg A, Monson L, et al. Radiomorphometric quantitative analysis of vasculature in rat mandible utilizing microcomputed tomography. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4S):26Y27. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duvall CL, Taylor WR, Weiss D, et al. Quantitative microcomputed tomography analysis of collateral vessel development after ischemic injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H302YH310. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00928.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Livingston Arinzeh T, Peter SJ, Archambault MP, et al. Allogeneic Mesenchymal Stem Cells Regenerate Bone in a Critical-Sized Canine Segmental Defect. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 2003;85:1927–1935. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200310000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Vlasselaer P, Borremans B, van Gorp U, Dasch JR, De Waal-Malefyt R. Interleukin 10 inhibits transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) synthesis required for osteogenic commitment of mouse bone marrow cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;124(4):569–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Wang L, Kikuiri1 T, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell–based tissue regeneration is governed by recipient T lymphocytes via IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha. Nature Medicine. 2011;17(12):1594–1602. doi: 10.1038/nm.2542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee DY, Cho T-J, Kim JA, Lee HR, Yoo WJ, Chung CY, Choi IH. Mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells in fracture healing and distraction osteogenesis. Bone. 2008;42:932–941. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Donneys A, Tchanque-Fossuo C, Farberg A, Deshpande S, Buchman S. Bone Regeneration In Distraction Osteogenesis Demonstrates Significantly Increased Vascularity In Comparison To Fracture Repair In The Murine Mandible [Abstract]. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;127:27. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e318241db26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000396725.25520.2a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rowe NM, Mehrara BJ, Luchs JS, Dudziak ME, Steinbrech DS, Illei PB, Longaker MT. Angiogenesis During Mandibular Distraction Osteogenesis. Annals of Plastic Surgery. 1999;42(5):470–475. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199905000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tsuchiya H, Uehara K, Sakurakichi K, Watanabe K, Matsubara H, Tomita K. Distraction osteogenesis after irradiation in a rabbit model. Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2005;10:627–633. doi: 10.1007/s00776-005-0945-1. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00776-005-0945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rhee ST, El-Bassiony L, Buchman SR. Extracellular Signal-Related Kinase and Bone Morphogenetic Protein Expression during Distraction Osteogenesis of the Mandible: In Vivo Evidence of a Mechanotransduction Mechanism for Differentiation and Osteogenesis by Mesenchymal Precursor Cells. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2006;117(7):2243–2249. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000224298.93486.1b. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.prs.0000224298.93486.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang C, Ogawa R. Mechanotransduction in bone repair and regeneration. The FASEB Journal. 2010;24(10):3625–3632. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-157370. http://dx.doi.org/10.1096/fj.10-157370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Al-Aql ZS, Alagl AS, Graves DT, Gerstenfeld LC, Einhorn TA. Molecular Mechanisms Controlling Bone Formation during Fracture Healing and Distraction Osteogenesis. Journal of Dental Research. 2008;87(2):107–118. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700215. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/154405910808700215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franceschi RT, Xiao G. Regulation of the osteoblast-specific transcription factor, Runx2: Responsiveness to multiple signal transduction pathways. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2003;88(3):446–454. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10369. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcb.10369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buttiglione M, Roca L, Montemurno E, Vitiello F, Capozzi V, Cibelli G. Radiofrequency radiation (900 MHz) induces Egr-1 gene expression and affects cell-cycle control in human neuroblastoma cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;213(3):759–767. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21146. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jcp.21146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pohl F, Hassel S, Nohe A, Flentje M, Knaus P, Sebald W, Koelbl O. Radiation-Induced Suppression of the Bmp2 Signal Transduction Pathway in the Pluripotent Mesenchymal Cell Line C2C12: An In Vitro Model for Prevention of Heterotopic Ossification by Radiotherapy. Radiation Research. 2003 2003 Mar;159(3):345–350. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0345:risotb]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song B, Estrada KD, Lyons KM. Smad signaling in skeletal development and regeneration. Cytokine and Growth Factor Reviews. 2009;20(5-6):379–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sakurai T, Sawada Y, Yoshimoto M, Kawai M, Miyakoshi J. Radiation-induced Reduction of Osteoblast Differentiation in C2C12 cells. Journal of Radiation Research. 2007;48(6):515–521. doi: 10.1269/jrr.07012. http://dx.doi.org/10.1269/jrr.07012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]