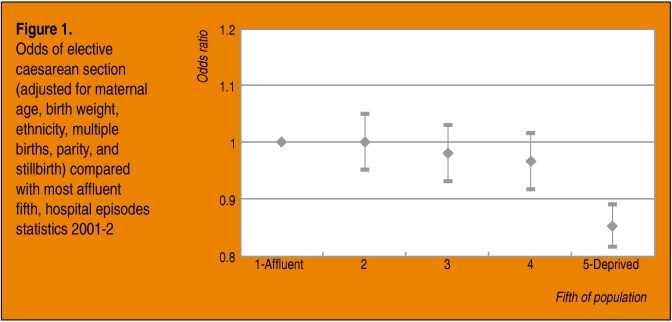

Over the past two decades the rising rate of caesarean section delivery in the United Kingdom and worldwide1 has led to concern that many caesarean sections are unnecessary. “Maternal request” is reported to be the fifth most common reason given for performing a caesarean section.2 Recently published NICE guidelines aim to reduce variations in caesarean rates around the country and guarantee consistent quality of care.3 Some commentators have blamed rising caesarean rates on wealthy women requesting the operation in the belief that it is less painful and avoids problems associated with natural delivery (thus the phrase “too posh to push”)4; others support the notion that the trend is provider led.5 An analysis of NHS hospital data for 2001-2 does not support the “too posh to push” concerns. Women living in the poorest fifth of areas are significantly less likely to have an elective caesarean, but otherwise increasing affluence is not associated with having an elective caesarean section.

The bottom line

• The odds of having an elective caesarean are lowest for women living in the most deprived areas of England, but otherwise there is no tendency towards having an elective caesarean section with increasing affluence

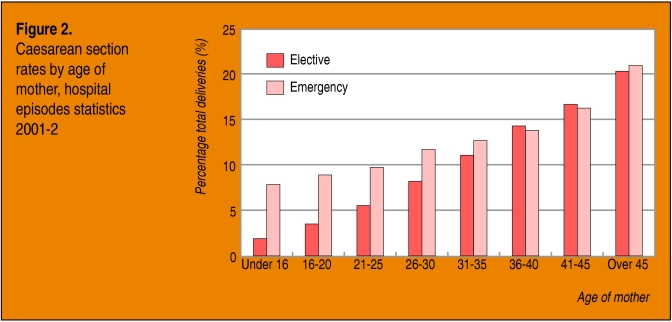

We examined hospital episode statistics data from 2001-2 and determined socioeconomic status on the basis of electoral ward of residence, using the index of multiple deprivation 2000.5 Odds ratios were calculated for each fifth of deprivation for elective caesarean section adjusted for maternal age, birth weight, ethnicity, multiple births, parity, and whether or not the birth was a stillbirth. Maternal age had the strongest independent influence on caesarean section rate. We found that women in the four most affluent fifths had similar odds of an elective caesarean, whereas the odds of having an elective caesarean were significantly lower in women living in the most deprived areas within England. We found no trend by socioeconomic deprivation for emergency caesarean sections.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

Hospital episode statistics recorded only 70% of births in 2001-2,6 but our overall caesarean section rates (20.1%) are broadly comparable with other sources (21.5%).7 Our figures do not include births in private hospitals, although there are only three private maternity hospitals in England, all of which are in London. The relatively small number of deliveries involved is unlikely to be a large source of bias. We do include private births in NHS hospitals. The deprivation score is area based, so it may not apply to all individuals within the area. We used variables available within hospital episode statistics to adjust for key confounders, but we were unable to adjust for factors such as obstetric complications, antenatal care, and previous caesareans and provider factors such as teaching status. Our results suggest that it is not so much a case of “too posh to push” within the NHS; it may be more a case of “too proletarian for a caesarean.”

The basic figures

Hospital episode statistics show 336 324 recorded deliveries out of a total of 541 700 births registered in England for 2001-26

The overall caesarean section rate was 20.1%

The elective caesarean section rate was 8.9%

The odds of an elective caesarean in the most deprived fifth of the population relative to the most affluent are 0.86 (95% confidence interval 0.82 to 0.89)

Supplementary Material

Dr Foster's Case Notes are compiled by Prof Brian Jarman, Dr Paul Aylin and Dr Alex Bottle of the Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College. Dr Foster is an independent research and publishing organisation created to examine measures of clinical performance.

Dr Foster's Case Notes are compiled by Prof Brian Jarman, Dr Paul Aylin and Dr Alex Bottle of the Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College. Dr Foster is an independent research and publishing organisation created to examine measures of clinical performance.

References and full methodological details are available on bmj.com and drfoster.com

References and full methodological details are available on bmj.com and drfoster.com

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.