Abstract

Peer assisted learning (PAL) is well documented in the medical education literature. In this paper, the authors explored the role of PAL in a graduate entry medical program with respect to the development of professional identity. The paper draws on several publications of PAL from one medical school, but here uses the theoretical notion of legitimate peripheral participation in a medical school community of practice to shed light on learning through participation. As medical educators, the authors were particularly interested in the development of educational expertise in medical students, and the social constructs that facilitate this academic development.

Keywords: medical school, community of practice, peer assisted learning, development, educational expertise

Introduction

Peer assisted learning (PAL) has been described as, “People from similar social groupings who are not professional teachers helping each other to learn and learning themselves by teaching.”1 PAL is well accepted as an educational method in many medical curricula, where participation and learning involves a process of socialization. During PAL activities, peers are dependent on each other’s relevant experiences and shared resources, and knowledge may be socially rather than individually constructed.2 Within medical schools, PAL provides a framework within which students can practice and improve their medical and teaching skills,3 helping to shape students’ professional values as they move into medical practice. This paper outlines the PAL activities in a medical school, views them through a theoretical lens of the medical school as a community of practice, and then focuses on the impact of PAL on students’ professional identity, with a special interest in their educational expertise.

Theoretical notions of communities of practice

The theoretical notion of communities of practice is frequently cited in the health profession’s education literature.4 Evolving from ethnographic studies of apprenticeships, it has been appropriated from its original context into clinical education.5 Fundamental to communities of practice is the notion that learning occurs through participation in activities important to the community. Newcomers are provided with meaningful and manageable tasks that contribute to the product of the community, that is, through legitimate peripheral participation.6 Participation enables newcomers to familiarize themselves with the language, tasks, processes, and organizing principles of the community, progressively becoming more central with increasing levels of responsibility. During this process, the participant develops an identity as a member of the community.6 Two important concepts influence legitimate peripheral participation. One relates to the “agency” of the individual, that is, the willingness of the individual to participate. The second relates to the “affordances” of the workplace, that is, the invitational quality of the “community.”

PAL in a medical school community of practice

Medical schools are communities of practice with goals different to the clinical settings in which students will eventually work. The authors posit that the PAL activities in this medical school provided students with legitimate peripheral participation by enabling them to take on teaching and assessment roles. Participation in these activities simultaneously developed new “professional” skills (educational expertise) while creating and consolidating medical knowledge and skills. The combination of this learning facilitated the development of students’ emerging identities as junior doctors. This all took place in the relative “safety” of the medical school community of practice.

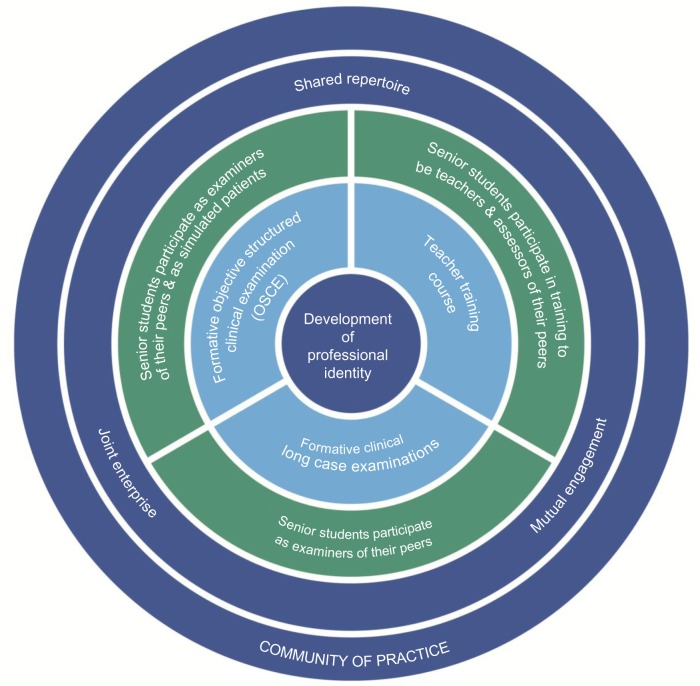

PAL at the Sydney Medical School consists of three activities, as illustrated in Figure 1: teacher training course, formative long case clinical examinations, and formative objective structured clinical examination (OSCE).

Figure 1.

Peer assisted learning program at Sydney Medical School – Central as a community of practice.

Teacher training course

The “Teaching on the Run” course is delivered as a six-module program over 18 hours. It provides theoretical background, practical examples, and active participation for medical students in a range of activities, including skills teaching, assessment, and training in the delivery of effective feedback in the clinical context.7

Formative long case clinical examinations

The long case examination requires students to undertake an unobserved physical examination and history taking of a patient for 1 hour; then, students are assessed for 20 minutes by two academic examiners on their presentation. In this formative version, students are required to act as an assessor of their peers, alongside an academic examiner. These examinations are designed to inform the students of their strengths and weaknesses in preparation for summative examinations.8

Formative objective structured clinical examination

The OSCEs require students to be examined at five stations, each assessing communication, examination, or procedural skills. In the formative OSCE, senior students assess junior students while other students act as simulated patients, that is, role playing as patients.9,10

Discussion

The impact of PAL on the school community

Participation in PAL consisted of voluntary and compulsory student activities. However, the focus on alignment of PAL with assessment made participation very attractive. Students had a common interest in studying medicine and were actively taking part in a model of learning at several levels and with academic staff. This collaborative, dynamic interplay helped to develop a social learning network. The teacher training course provided a foundation for the PAL activities, with students claiming that the academic facilitators were “fostering a changing culture.”7 Voluntary participation in the teacher training course almost doubled over 3 years (32%–57%) and similarly in the formative OSCEs (25%–41%). Although participation in the formative long case examinations was compulsory, students valued highly the opportunity to engage with academic staff as colleagues.

As PAL participation increased, a supportive and professional culture evolved within the student community. Students were not only taking part to reinforce their own medical knowledge, but saw participation as a way to “support other students” and provide feedback and “tips” based on what they had learnt from their “own exams,” and develop their own teaching and assessment skills, an element of educational expertise.9 The student body’s joint enterprise, mutual engagement, and shared repertoire11 in the PAL activities enriched the social capital of the clinical school. The program was awarded the University Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Support of the Student Experience.12

Identity-based curriculum

Medical students have many different roles within and across their clinical school, their medical faculty, university, and beyond, and so a focus on professional identity formation is relevant in contemporary medical curricula.13 PAL emphasizes the professional expectations of the students as medical graduates. Teaching, assessment, and communication skills are increasingly recognized internationally by universities and medical councils as requisite graduate competences.14 PAL has enabled these expectations to be met by providing students with opportunities to learn, understand, and develop these skills. Senior students undertake meaningful educational tasks that they must train and prepare for, mirroring the roles they will assume as junior medical staff.9 By participating in PAL, students recognize the importance of these skills within medicine and associate these attributes with their identity as medical students and future medical practitioners, helping to foster a life-long culture of teaching.14

Development of professional relationships

Although most medical programs are now vertically integrated with early clinical exposure, limited faculty availability for teaching is well recognized as a problem within medical education.15,16 The PAL activities facilitated senior students’ interaction with senior academics. Students had role models close at hand, and felt privileged to be in such a position. Academic staff treated the students as colleagues,17 reinforcing students’ identity as valuable members of the school community.

Inclusive activities

Medical education can be viewed as a process of socialization, which helps to redefine the task of medical educators.18 The social context of the PAL activities induced communal engagement, shaping the culture of the learning environment.17 The interactions of junior and senior students, sharing their expertise within a contextual clinical framework, prompted collaborative student engagement. Although junior students are on the boundaries of the school’s community of practice, they are important participants. The first years of medical school can be socially isolating for students, but PAL activities facilitate junior and senior student exchange in a formal, professional context. At the same time, the PAL process helps to establish the professional identity of senior students who are expected to have enough medical knowledge and professionalism skills to act as assessors and formulate peer feedback. Although not given the scope to practice their own teaching and assessment skills, junior students develop an appreciation of their own future role and responsibilities as senior members of the student community.

Proficiency and responsibilities of students

In PAL, order, engagement, and commitment from participants are achieved through careful planning and preparation.19 Student assessors were required to attend training sessions and prepare for the activities. Students became familiar with the resources, assessment methods, marking domains, marking criteria, and feedback techniques. By allowing students to assess their peers in the formative OSCEs and long cases, their responsibilities were aligned with their abilities, and competence was developed.19 Students become active participants in the development of their own professional identity.

Conclusion

This paper reflected on PAL practices within a medical school, exploring students’ academic development through social constructs. The PAL program acts as a dynamic tool in shaping the school’s community of practice, positively impacting its culture, and adding to its social capital. Participation in PAL helps students to establish their professional identity and recognize their significant roles and responsibilities as medical students and their future roles as medical practitioners with teaching, assessment, and life-long learning responsibilities.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Topping KJ. The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: a typology and review of the literature. Higher Education. 1996;32(3):321–345. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Swanwick T. Informal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to “culturism”. Med Educ. 2005;39(8):859–865. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardach NS, Vedanthan R, Haber RJ. “Teaching to teach”: enhancing fourth year medical students’ teaching skills. Med Educ. 2003;37(11):1031–1032. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li LC, Grimshaw J, Nielsen C, Judd M, Coyte PC, Graham ID. Use of communities of practice in business and health care sectors: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2009;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morris C. Replacing “the firm”: re-imagining clinical placements as time spent in communities of practice. In: Cook V, Daly C, Newman M, editors. Work Based Learning in Clinical Settings – Insights from Socio-Cultural Perspectives. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical; 2012. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lave J, Wenger E. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burgess A, Black K, Chapman R, Clark T, Roberts C, Mellis C. Clinical teaching skills for students: our future educators. Clin Teach. 2012;9(5):312–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-498X.2012.00554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgess A, Roberts C, Black K, Mellis C. Senior medical student perceived ability and experience in giving feedback in formative long case examinations. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:79. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burgess A, Clark T, Chapman R, Mellis C. Senior medical students as peer examiners in an OSCE. Med Teach. 2013;35(1):58–62. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.731101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burgess A, Clark T, Chapman R, Mellis C. Medical student experience as simulated patients in the OSCE. Clin Teach. 2013;10:246–250. doi: 10.1111/tct.12016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wenger E. Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning, and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.2013 vice-chancellor award winners [webpage on the Internet] Sydney: The University of Sydney; 2013. [Accessed March 6, 2014]. [cited July 5, 2013]. Available from: http://www.itl.usyd.edu.au/awards/2013_awardwinners.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu TC, Wilson NC, Singh PP, Lemanu DP, Hawken SJ, Hill AG. Medical students-as-teachers: a systematic review of peer-assisted teaching during medical school. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2011;2:157–172. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S14383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooke M, Irby DM, O’Brien BC. Educating Physicians: A Call for Reform of Medical School and Residency. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahlstrom J, Dorai-Raj A, McGill D, Owen C, Tymms K, Watson DA. What motivates senior clinicians to teach medical students? BMC Med Educ. 2005;5:27. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-5-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehta NB, Hull AL, Young JB, Stoller JK. Just imagine: new paradigms for medical education. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1418–1423. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a36a07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schumacher DJ, Englander R, Carraccio C. Developing the master learner: applying learning theory to the learner, the teacher, and the learning environment. Acad Med. 2013;88(11):1635–1645. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a6e8f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dornan T, Bundy C. What can experience add to early medical education? Consensus survey. BMJ. 2014;329(7470):834. doi: 10.1136/bmj.329.7470.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraser SW, Greenhalgh T. Coping with complexity: educating for capability. BMJ. 2001;323(7316):799–803. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7316.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]