Abstract

Objective To compare the effects of low concentration epidural infusions of bupivacaine with parenteral opioid analgesia on rates of caesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery in nulliparous women.

Data sources Medline, Embase, the Cochrane controlled trials register, and handsearching of the International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia.

Study selection Randomised controlled trials comparing low concentration epidural infusions with parenteral opioids.

Data synthesis Seven trials fulfilled the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis. Epidural analgesia does not seem to be associated with an increased risk of caesarean section (odds ratio 1.03, 95% confidence interval 0.71 to 1.48) but may be associated with an increased risk of instrumental vaginal delivery (2.11, 0.95 to 4.65). Epidural analgesia was associated with a longer second stage of labour (weighted mean difference 15.2 minutes, 2.1 to 28.2 minutes). More women randomised to receive epidural analgesia had adequate pain relief, with fewer changing to parenteral opioids than vice versa (odds ratio 0.1, 0.05 to 0.22).

Conclusions Epidural analgesia using low concentration infusions of bupivacaine is unlikely to increase the risk of caesarean section but may increase the risk of instrumental vaginal delivery. Although women receiving epidural analgesia had a longer second stage of labour, they had better pain relief.

Introduction

It was not until the second half of the 20th century that effective analgesia for labour pain was introduced in the form of indwelling epidural catheters, providing continuous effective pain relief. Currently over half of parturient women in the United States and about a fifth in England and Wales receive epidural analgesia.1,2 The dose of anaesthetic can be adjusted for deliveries by forceps or caesarean, thus avoiding general anaesthesia.

Although regional anaesthesia has been associated with a reduction in anaesthesia related maternal mortality, there is continuing controversy over whether epidural analgesia impedes the progress of labour by causing dystocia and increasing operative delivery rates.3-5 Evidence is unclear as previous reviews have included disparate regimens for epidural analgesia and women of mixed parity.6-8

We focused on epidural infusions containing low concentrations of local anaesthetic as these are associated with a lower risk of operative delivery.9 To overcome the confounding effect of parity, we selected nulliparous women, who have a higher risk of dystocia. We assessed all operative deliveries (caesarean section, forceps, vacuum assisted) because limiting analysis to caesarean section would disguise the impact of epidural analgesia on mode of delivery.

Methods

We searched Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane controlled trials register for all relevant clinical reports published before June 2003 using thesaurus and MeSH terms for epidural analgesia, labour, forceps, vacuum assisted delivery, caesarean section, and instrumental delivery. Titles and abstracts of references were reviewed online. The contents of the International Journal of Obstetric Anesthesia were hand searched. Relevant studies were those where abstracts described women treated with epidural analgesia and mode of delivery. We searched the bibliographies of these studies for other reports.

Selection and validity assessment

We identified potentially relevant randomised controlled trials, excluding retrospective studies. Trials were selected for evaluation that specifically addressed whether epidural analgesia affected the risk of instrumental delivery. We then selected trials in which epidural infusions of low concentration local anaesthetic were compared with parenteral opioids and where the epidural infusions were continued during the second stage of labour. Trials using high concentration boluses of anaesthetic instead of infusions were excluded.

Trial validity was assessed using the Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network checklist.10 Criteria included randomisation, allocation concealment, blinding, similarity of groups at the start of the study, equal treatment of groups, measurement of outcomes, losses to follow up, and intention to treat analysis. The authors independently assessed and scored each article. Trials for data abstraction were selected only when all or most of the criteria for validity had been fulfilled, and when those not fulfilled were unlikely to alter the conclusions.

Data abstraction and synthesis and study characteristics

The authors independently abstracted data in duplicate and cross checked for transcription errors and discrepancies. Trials included for meta-analysis used low concentrations of bupivacaine (≤ 0.125%) in continuous epidural infusions during the first two stages of labour in nulliparous women. All the trials had outcomes for caesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery.

Results of the trials were combined using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Program (Biostat, Englewood, NJ, USA). We used odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for categorical outcomes and weighted mean differences for continuous outcomes. Random effects models were used for all analyses, and heterogeneity was assessed. Sensitivity analyses were carried out if there was heterogeneity in the outcome measures.

Results

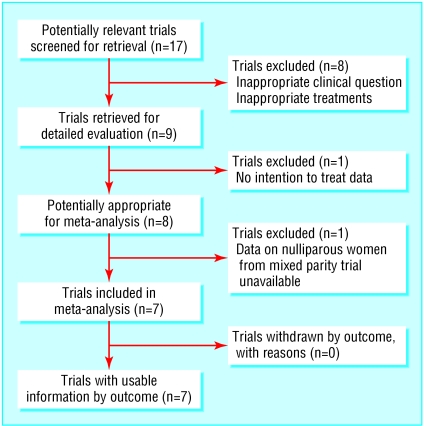

Our search identified 17 potentially relevant randomised controlled trials (fig 1 and table 1). Two trials assessed whether continuing epidural analgesia in the second stage of labour influenced the mode of delivery, and these compared local anaesthetic with saline epidural infusions during the second stage of labour.11,12 One trial compared starting epidural analgesia early in labour with starting it late.13 As these three trials addressed different questions and had no parenteral opioid comparator, we excluded them from the meta-analysis. We also excluded four trials using high concentration bupivacaine boluses (0.375% and 0.5%14-17) and one trial using bupivacaine 0.25% boluses.18

Fig 1.

Flow of randomised controlled trials in meta-analysis

Table 1.

Randomised controlled trials comparing risk of instrumental vaginal delivery associated with epidural analgesia or parenteral opioids

| Trial; country | Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network score* | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Bofill et al, 199723; United States | +, not blinded | Nulliparous women; included in meta-analysis |

| Chestnut et al, 198711; United States | NA | Nulliparous women; excluded, as study compared 0.75% lignocaine with saline epidural infusions during second stage labour |

| Chestnut et al 198712, United States | NA | Nulliparous women; excluded, as study compared 0.125% bupivacaine with saline epidural infusions during second stage labour |

| Chestnut et al, 199413; United States | NA | Nulliparous women; excluded as study compared early with late institution of bupivacaine epidural analgesia |

| Clark et al, 199824; United States | +, not blinded | Nulliparous women; included in meta-analysis |

| Dickinson et al, 200227; Australia | +, not blinded | Nulliparous women; included in meta-analysis, separate data available for women with spontaneous and induced labour |

| Gambling et al, 199821; United States | +, not blinded | Mixed parity women; nulliparous data not available |

| Howell et al, 200118; United Kingdom | NA | Nulliparous women; excluded as study used bupivacaine 0.25% boluses |

| Loughnan et al, 200025; United Kingdom | +, not blinded | Nulliparous women; included in meta-analysis |

| Nikkola et al, 199717; Finland | NA | Nulliparous women; excluded as study used bupivacaine 0.5% boluses, which were stopped in second stage labour |

| Noble et al, 197116; United Kingdom | NA | Mixed parity women; excluded as study used bupivacaine 0.5% boluses |

| Philipsen and Jensen, 198914; Denmark | NA | Mixed parity women; excluded as study used bupivacaine 0.375% boluses |

| Ramin et al, 199519; United States | −, not blinded, no intention to treat data | Mixed parity women; nulliparous data not available |

| Robinson et al, 198015; United Kingdom | NA | Mixed parity women; excluded as study used bupivacaine 0.5% boluses |

| Sharma et al, 199720; United States | +, not blinded | Mixed parity women; data on nulliparous women available only for caesarean section meta-analysis |

| Sharma et al, 200226; United States | +, not blinded | Nulliparous women; included in meta-analysis |

| Thorp et al, 199322; United States | +, not blinded | Nulliparous women; included in meta-analysis |

NA=not assessed.

Positive and minus signs indicate how well study minimised bias.

One trial with women of mixed parity did not provide intention to treat data.19 The remaining eight trials fulfilled the criteria for inclusion in the meta-analysis.20-27 Two of these were trials with women of mixed parity.20,21 After contacting the authors, we were able to obtain data on overall caesarean section rate for only one of these trials.20

All seven included trials had adequate allocation concealment. Treatment groups were similar at the start of the trials and seemed to have been treated equally. Intention to treat analyses were performed, and there were no losses to follow up. In none of the trials were the patients or investigators blinded.

These seven trials used low concentration bupivacaine infusions (0.125% or 0.0625%) but varied in the addition of opioids (table 2). They included women only with full term uncomplicated pregnancies with cephalic presentation. One trial included patients in both spontaneous and induced labour, with separate data for those in spontaneous labour.27

Table 2.

Details of included trials of women receiving epidural infusions of low concentration local anaesthetic or parenteral opioids

|

Protocol

|

Criteria for operative intervention

|

Analgesia protocol

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial | Labour | Oxytocin | Epidural | Parenteral opioids | Crossover rate | |

| Bofill et al, 199723 | Spontaneous labour; active management of labour; early amniotomy and hourly pelvic examinations | 6 mU/min, increased by 6 mU every 30 minutes up to maximum 42 mU/min if cervical dilation <1 cm/h | Decision for caesarean section made after consulting perinatologist blinded to treatment allocation; elective forceps delivery allowed | Induction: epidural 3 ml 1.5% lignocaine with 1:200 000 adrenaline and 3-5 ml 0.25% bupivacaine with or without 50-100 μg fentanyl; maintenance: infusion 0.125% bupivacaine and 1.5 μg/ml fentanyl to maintain T10 level | Intravenous 1 or 2 mg butorphanol as required | 0/49 in epidural group; 12/51 in opioid group |

| Clark et al, 199824 | Spontaneous labour; intrauterine pressure catheter and fetal scalp electrode placed at amniotomy | 6 mU/min, increased by 6 mU every 15 minutes until seven contractions in 15 minutes or until cervix dilation >1 cm/h | Criteria for caesarean section defined; elective forceps delivery allowed | Induction: epidural 3 ml 1% lignocaine and adrenaline, then 9 ml 0.25% bupivacaine with 50 μg fentanyl; maintenance: infusion 0.125% bupivacaine and 1 μg/ml fentanyl at 12 ml/h to achieve T10 block | Intravenous pethidine 50-75 mg as required every 90 minutes | 5/156 in epidural group; 84/162 in opioid group |

| Dickinson et al, 200227 | Spontaneous and induced labour; electronic fetal heart and intrauterine pressure transducers not routinely used; dystocia defined as failure of progress of cervical dilation in 2-4 hours | 2 mU/min if cervix dilation <1 cm/h, increased by 2 mU/min at 30 minute intervals to maximum 36 mU/min | Not specified | Induction: combined spinal 25 μg fentanyl and bupivacaine 2 mg with epidural 0.125% bupivacaine 6 ml; or epidural 0.125% bupivacaine 10 ml and fentanyl 5 μg/ml; maintenance: patient controlled epidural analgesia 0.1% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg/ml, 4 ml bolus, 15 minute lockout | Intramuscular pethidine 1.5 mg/kg | 137/493 epidural group; 306/499 opioid group |

| Loughnan et al, 200025 | Spontaneous and induced labour; active management; written protocol; pelvic examinations every two hours; all women given nitrous oxide for pain relief | 4 mU/min, increased every 15 minutes up to maximum of 40 mU/min if cervix dilation <1 cm/h | Not specified | Induction: epidural 0.125% bupivacaine 10-15 ml; maintenance infusion: 0.125% bupivacaine at 10-15 ml/h | Intramuscular pethidine 100 mg every two hours up to 300 mg | 44/304 in epidural group; 175/310 in opioid group |

| Sharma et al, 199720 | Mixed parity; spontaneous labour; written protocol; cervical examinations every two hours; continuous internal monitoring for high risk cases; intrauterine pressure monitoring before starting oxytocin | 6 mU/min if cervix dilation <1 cm/h, increased by 6 mU/min every 40 minutes up to 42 mU/min | Criteria defined for inadequate progress, low forceps if inadequate voluntary pushing or fetal heart rate abnormalities | Induction: epidural 0.25% bupivacaine in 3 ml increments until T10 block; maintenance: infusion 0.125% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg/ml at 8-10 ml/h | Intravenous bolus pethidine 50mg and promethazine 25 mg, then patient controlled pethidine 10 mg every 10 minutes in first hour, then 15 mg every 10 minutes, additional 25 mg boluses on request | 8/358 epidural group; 5/357 opioid group |

| Sharma et al, 200226 | Spontaneous labour; written protocol; cervical examinations every two hours; continuous internal monitoring for high risk cases; intrauterine pressure monitoring before starting oxytocin | 6 mU/min if cervix dilation <1 cm/h, increased by 6 mU/min every 40 minutes up to 42 mU/min | Criteria defined for inadequate progress, low forceps if inadequate voluntary pushing or fetal heart rate abnormalities | Induction: epidural 3 ml 1.5% lignocaine and 0.25% bupivacaine in 3 ml increments until T10 block; maintenance: infusion 0.0625% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2 μg/ml at 6 ml/h, and patient controlled epidural analgesia 5 ml bolus, 15 minute lockout | Intravenous bolus pethidine 50 mg and promethazine 25 mg, then patient controlled pethidine 15 mg every 10 minutes up to maximum 100 mg in two hours | 0/226 epidural group; 14/233 opioid group |

| Thorp et al, 199322 | Spontaneous labour; electronic fetal monitoring in all patients; fetal distress diagnosed from abnormal tracing or scalp pH; internal uterine pressure monitoring undertaken | 1 mU/min, increased by 1 mU/min every 30-45 minutes | Criteria defined, caesarean for fetal distress if abnormal scalp pH or ominous heart rate tracing, caesarean for dystocia if arrest of cervical dilation in 1st stage of labour or arrest of descent in 2nd stage | Induction: epidural 0.25% bupivacaine bolus; maintenance: infusion 0.125% bupivacaine to maintain T10 block | Intravenous pethidine 75 mg and promethazine 25 mg every 90 minutes as required | 0/48 in epidural group; 1/45 in opioid group |

Quantitative data analysis

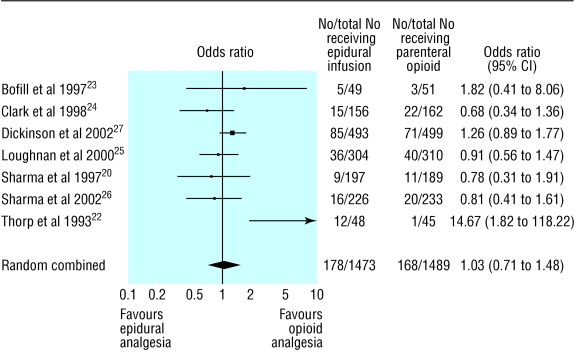

Caesarean section

Data were analysed for 2962 nulliparous women (table 3).20,22-27 We found no statistically significant difference in the rates of caesarean section between women receiving epidural analgesia and those receiving parenteral opioids (odds ratio 1.03, 95% confidence interval 0.71 to 1.48; fig 2). One trial showed a greatly increased risk of caesarean section with epidural analgesia.22 This small trial caused heterogeneity in the meta-analysis; when we excluded it from sensitivity analysis, the risk was slightly changed (1.01, 0.80 to 1.28) and there was no heterogeneity. Separate analyses of caesarean section rates for dystocia and for fetal distress also showed no significant differences (1.00, 0.64 to 1.58 and 1.15, 0.79 to 1.67, respectively). Analysis including only women in spontaneous labour also showed no significant difference (1.08, 0.65 to 1.82).

Table 3.

Outcomes of trials of women receiving epidural infusions of low concentration local anaesthetic or parenteral opioids

| Outcome | References of trials | No (total No) in epidural group | No (total No) in opioid group | Odds ratio (95% CI) | % rate difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caesarean section: | |||||

| Overall | 20; 22-27 | 178/1473 | 168/1489 | 1.03 (0.71 to 1.48) | 1.18 (−2.66 to 5.01) |

| Excluding Thorp 1993 | 20; 23-27 | 166/1425 | 167/1444 | 1.01 (0.80 to 1.28) | −0.29 (−2.49 to 1.90) |

| Dystocia | 22-27 | 102/1276 | 99/1300 | 1.00 (0.64 to 1.58) | 0.42 (−2.91 to 3.74) |

| Fetal distress | 22-27 | 64/1276 | 55/1300 | 1.15 (0.79 to 1.67) | 0.59 (−0.79 to 1.97) |

| Patients in spontaneous labour | 22-24; 26; 27 | 87/942 | 82/954 | 1.08 (0.65 to 1.82) | 1.65 (−2.99 to 6.29) |

| Instrumental vaginal delivery: | |||||

| Overall | 22-27 | 355/1276 | 289/1300 | 1.63 (1.12 to 2.37) | 6.19 (2.46 to 9.91) |

| Excluding elective forceps | 22; 25-27 | 292/1071 | 241/1087 | 1.56 (0.99 to 2.46) | 6.16 (3.00 to 9.33) |

| Excluding elective forceps and induced labour | 22; 26; 27 | 132/540 | 92/552 | 2.11 (0.95 to 4.65) | 8.14 (4.25 to 12.03) |

| Total operative delivery: | |||||

| Caesarean section, forceps, and vacuum assisted deliveries | 22-27 | 524/1276 | 446/1300 | 1.63 (1.09 to 2.42) | 9.70 (2.40 to 17.00) |

| Excluding elective forceps | 22; 25-27 | 441/1071 | 373/1087 | 1.55 (1.03 to 2.32) | 8.57 (1.48 to 15.65) |

| Mean duration of second stage (minutes) | 22-24; 26 | 64.5 | 49.3 | 15.2* (2.1 to 28.2) | — |

| Non-compliance with treatment allocation | 22-27 | 221/1276 | 607/1300 | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.33) | −23.73 (−41.40 to −6.03) |

| Cross over to other treatment | 22-27 | 186/1276 | 592/1300 | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.22) | −25.83 (−46.65 to −5.01) |

| Oxytocin: | |||||

| Required after analgesia | 22; 26 | 121/274 | 87/278 | 1.75 (1.23 to 2.48) | 13.19 (5.22 to 21.16) |

| Use overall | 22-24; 26; 27 | 467/783 | 424/799 | 1.35 (0.88 to 2.07) | 6.72 (−2.72 to 16.17) |

| Neonate details: | |||||

| Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes | 22; 24; 26; 27 | 13/923 | 17/939 | 0.72 (0.26 to 2.04) | −0.55 (−2.21 to 1.12) |

| Umbilical artery pH <7.2 | 22; 24; 26 | 23/423 | 31/418 | 0.72 (0.40 to 1.27) | −2.45 (−5.51 to 0.61) |

| Required naloxone | 23; 26 | 0/275 | 14/284 | 0.10 (0.01 to 0.89) | −4.38 (−7.77 to −0.99) |

Mantel-Haenszel random effects models used in all analyses.

Weighted mean difference.

Fig 2.

Rates of caesarean section in trials of nulliparous women receiving epidural analgesia or parenteral opioids

Other maternal outcomes

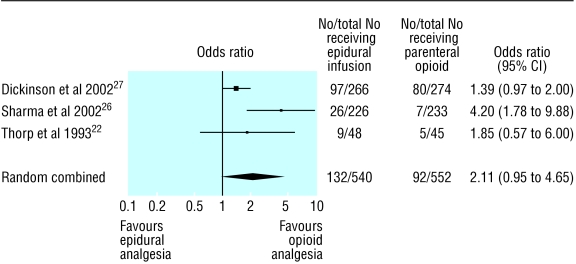

We found a statistically significant increase in rates of instrumental vaginal delivery with epidural analgesia (1.63, 1.12 to 2.37). However, two trials included elective forceps delivery and forceps deliveries for training purposes,23,24 and two other trials included women who had their labour induced.25,27 When we excluded data for women who had labour induced and those who had elective forceps delivery, the risk was higher but not significant (2.11, 0.96 to 4.65; fig 3). Total operative delivery was higher with epidural analgesia (1.63, 1.09 to 2.42). This risk was slightly reduced when we excluded the two trials with elective forceps deliveries and forceps deliveries for training purposes (1.55, 1.03 to 2.32). Epidural analgesia was associated with a longer second stage of labour (weighted mean difference 15.2 minutes, 2.1 to 28.2 minutes). Non-compliance with allocated analgesia was much less with epidural analgesia (0.19, 0.11 to 0.33). Fewer women changed from the epidural group to the opioid group than vice versa (0.10, 0.05 to 0.22).

Fig 3.

Rates of instrumental vaginal delivery and odds ratios in trials of nulliparous women receiving epidural analgesia or parenteral opioids; trials were excluded when elective forceps were permitted or where labour was induced

Neonatal outcomes

Fewer neonates in the epidural groups had Apgar scores of less than 7 at five minutes and umbilical artery pHs of less than 7.2, but these differences were not statistically significant (0.72, 0.26 to 2.04 and 0.72, 0.40 to 1.27, respectively). Although only two trials provided data on requirement of nalaxone by neonates, it was lower in neonates whose mothers had had epidural analgesia (0.1, 0.01 to 0.89).

Discussion

Nulliparous women who receive epidural analgesia during labour do not seem to be at an increased risk of delivery by caesarean section; the wide confidence intervals introduce some uncertainty. Epidural analgesia may be associated with a higher risk of instrumental vaginal delivery. Although epidural analgesia was associated with a longer second stage of labour, neonates seemed unharmed. We found no worsening of Apgar scores or umbilical acid-base status in neonates whose mothers had received epidural analgesia, despite the increased risk of instrumental vaginal delivery. These neonates were also less likely to need naloxone than neonates whose mothers received opioid analgesia.

One limitation of these trials is the disparity in the quality of pain relief between epidural analgesia and parenteral opioids, which would have made blinding of clinicians difficult. Bias may have been present owing to a lower threshold for performing instrumental vaginal delivery in the presence of epidural analgesia. Two trials did not have strict indications for instrumental vaginal delivery. These permitted elective forceps delivery or assisted vaginal delivery for training purposes and had to be excluded from analysis of risk of instrumental vaginal delivery.23,24 Even then there was a clinically important increase in risk. Differences in protocols for management of labour could have contributed to the differences in rates of instrumental vaginal delivery.

Another limitation was the large number of women who changed to epidural analgesia despite being randomised to parenteral opioids. Our intention to treat approach would likely render any estimation of the effects of epidural analgesia more conservative, but it was necessary to prevent selection bias. Comparing a policy of offering epidural analgesia with one of offering parenteral opioids reflects real life. In contrast, analysing data from participants who are compliant with allocation would bias the epidural group to have mainly patients with more severe pain and presumably more complicated labour, whereas the opposite would be the case for the opioid group.

As the definitions of stages of labour varied between trials, we were unable to determine if epidural analgesia prolonged the first stage, and the actual duration can only be estimated.

Unlike previous reviews, we focused on nulliparous women because the indications for, and risks of, caesarean section differ with parity. The major indication in nulliparous women is dystocia, whereas in multiparous women it is previous caesarean section.27 Our analysis does not support an association between epidural analgesia and an increased risk of caesarean delivery for dystocia. But the analysis does support an association with an increased risk of instrumental vaginal delivery, which can cause maternal dissatisfaction and trauma and fetal trauma and can have a substantial impact on workload and safety.

We limited our analysis to trials that used infusions of bupivacaine with concentrations of 0.125% or less, to reflect current practice. In a randomised controlled trial, low concentrations have been shown to reduce the rate of instrumental delivery.9

Epidural analgesia may increase the risk of instrumental delivery by several mechanisms. Reduction of serum oxytocin levels can result in a weakening of uterine activity.28,29 This may be due in part to intravenous fluid infusions being given before epidural analgesia, reducing oxytocin secretion.30 The increased use of oxytocin after starting epidural analgesia may indicate attempts at speeding up labour. Maternal efforts at expulsion can also be impaired, causing fetal malposition during descent.31 Previously, the association of neonatal morbidity and mortality with longer labour (second stage longer than two hours) had justified expediting delivery, leading to increased rates of instrumental delivery.32

Delaying maternal pushing until the fetus's head is visible or until one hour after reaching full cervical dilation may reduce the incidence of instrumental delivery and its attendant morbidity.32 Although patients receiving epidural analgesia had a longer second stage labour, this was not associated with poorer neonatal outcome in our analysis. With increasing use of continuous electronic fetal monitoring, a longer but more comfortable labour may cause little harm to the neonate.

It is doubtful whether epidural analgesia with low concentration bupivacaine increases the risk of caesarean section or harms neonates. Fears about an increased risk of caesarean section should not be used to discourage epidural analgesia in nulliparous women if requested.

What is already known on this topic

Epidural analgesia during labour is effective but has been associated with increased rates of instrumental delivery

Studies have included women of mixed parity and high concentrations of epidural anaesthetic

What this study adds

Epidural infusions with low concentration local anaesthetics are unlikely to increase the risk of caesarean section in nulliparous women

Although epidural analgesia is associated with an increased risk of instrumental vaginal delivery, operator bias cannot be excluded

Epidural analgesia is associated with a longer second stage labour and increased oxytocin requirement, but the importance of these is unclear as maternal analgesia and neonatal outcome may be better with epidural analgesia

We thank Christopher R Palmer (University of Cambridge) for guiding us and Shiv Sharma (University of Texas Southwestern Medical Centre) for helping with the data.

Contributors: EL conceptualised the review. EL and AS independently searched for, collated, assessed, and analysed the data, and cowrote the paper. EL will act as guarantor for the paper.

Funding: None.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Not required.

References

- 1.Hawkins JL, Gibbs CP, Orleans M, Martin-Salvaj G, Beaty B. Obstetric anesthesia work force survey, 1981 versus 1992. Anesthesiology 1997;87: 135-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Findley I, Chamberlain G. ABC of labour care. Relief of pain. BMJ 1999;318: 927-30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hawkins JL, Koonin LM, Palmer SK, Gibbs CP. Anesthesia-related deaths during obstetric delivery in the United States, 1979-1990. Anesthesiology 1997;86: 277-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chestnut DH. Anesthesia and maternal mortality. Anesthesiology 1997;86: 273-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts CL, Algert CS, Douglas I, Tracy SK, Peat B. Trends in labour and birth interventions among low-risk women in New South Wales. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;42: 176-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halpern SH, Leighton BL, Ohlsson A, Barrett JF, Rice A. Effect of epidural vs parenteral opioid analgesia on the progress of labor: a meta-analysis. JAMA 1998;280: 2105-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Klebanoff MA, DerSimonian R. Epidural analgesia in association with duration of labor and mode of delivery: a quantitative review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1999;180: 970-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Howell CJ. Epidural versus non-epidural analgesia for pain relief in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000; CD000331. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Comparative Obstetric Mobile Epidural Trial (COMET) Study Group UK. Effect of low-dose mobile versus traditional epidural techniques on mode of delivery: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2001;358: 19-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Methodology checklist 2: randomised controlled trials. www.sign.ac.uk/guidelines/fulltext/50/checklist2.html (accessed 7 Mar 2004).

- 11.Chestnut DH, Bates JN, Choi WW. Continuous infusion epidural analgesia with lidocaine: efficacy and influence during the second stage of labor. Obstet Gynecol 1987;69: 323-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chestnut DH, Vandewalker GE, Owen CL, Bates JN, Choi WW. The influence of continuous epidural bupivacaine analgesia on the second stage of labor and method of delivery in nulliparous women. Anesthesiology 1987;66: 774-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chestnut DH, McGrath JM, Vincent RD Jr, Penning DH, Choi WW, Bates JN, et al. Does early administration of epidural analgesia affect obstetric outcome in nulliparous women who are in spontaneous labor? Anesthesiology 1994;80: 1201-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philipsen T, Jensen NH. Epidural block or parenteral pethidine as analgesic in labour; a randomized study concerning progress in labour and instrumental deliveries. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1989;30: 27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinson JO, Rosen M, Evans JM, Revill SI, David H, Rees GA. Maternal opinion about analgesia for labour. A controlled trial between epidural block and intramuscular pethidine combined with inhalation. Anaesthesia 1980;35: 1173-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noble AD, Craft IL, Bootes JA, Edwards PA, Thomas DJ, Mills KL. Continuous lumbar epidural analgesia using bupivacaine: a study of the fetus and newborn child. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1971;78: 559-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nikkola EM, Ekblad UU, Kero PO, Alihanka JJ, Salonen MA. Intravenous fentanyl PCA during labour. Can J Anaesth 1997;44: 1248-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howell CJ, Kidd C, Roberts W, Upton P, Lucking L, Jones PW, et al. A randomised controlled trial of epidural compared with non-epidural analgesia in labour. Br J Obstetric Gynaecol 2001;108: 27-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramin SM, Gambling DR, Lucas MJ, Sharma SK, Sidawi JE, Leveno KJ. Randomized trial of epidural versus intravenous analgesia during labor. Obstet Gynecol 1995;86: 783-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma SK, Sidawi JE, Ramin SM, Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Cunningham FG. Cesarean delivery: a randomized trial of epidural versus patient-controlled meperidine analgesia during labor. Anesthesiology 1997;87: 487-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gambling DR, Sharma SK, Ramin SM, Lucas MJ, Leveno KJ, Wiley J, et al. A randomized study of combined spinal-epidural analgesia versus intravenous meperidine during labor: impact on cesarean delivery rate. Anesthesiology 1998;89: 1336-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thorp JA, Hu DH, Albin RM, McNitt J, Meyer BA, Cohen GR, et al. The effect of intrapartum epidural analgesia on nulliparous labor: a randomized, controlled, prospective trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169: 851-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bofill JA, Vincent RD, Ross EL, Martin RW, Norman PF, Werhan CF, et al. Nulliparous active labor, epidural analgesia, and cesarean delivery for dystocia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1997;177: 1465-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark A, Carr D, Loyd G, Cook V, Spinnato J. The influence of epidural analgesia on cesarean delivery rates: a randomized, prospective clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;179: 1527-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loughnan BA, Carli F, Romney M, Dore CJ, Gordon H. Randomized controlled comparison of epidural bupivacaine versus pethidine for analgesia in labour. Br J Anaesth 2000;84: 715-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma SK, Alexander JM, Messick G, Bloom SL, McIntire DD, Wiley J, et al. Cesarean delivery: a randomized trial of epidural analgesia versus intravenous meperidine analgesia during labor in nulliparous women. Anesthesiology 2002;96: 546-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickinson JE, Paech MJ, McDonald SJ, Evans SF. The impact of intrapartum analgesia on labour and delivery outcomes in nulliparous women. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 2002;42: 59-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goodfellow CF, Hull MG, Swaab DF, Dogterom J, Buijs RM. Oxytocin deficiency at delivery with epidural analgesia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1983;90: 214-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bates RG, Helm CW, Duncan A, Edmonds DK. Uterine activity in the second stage of labour and the effect of epidural analgesia. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985;92: 1246-50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheek TG, Samuels P, Miller F, Tobin M, Gutsche BB. Normal saline i.v. fluid load decreases uterine activity in active labour. Br J Anaesth 1996;77: 632-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newton ER, Schroeder BC, Knape KG, Bennett BL. Epidural analgesia and uterine function. Obstet Gynecol 1995;85: 749-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller AC. The effects of epidural analgesia on uterine activity and labor. Int J Obstet Anesth 1997:6: 2-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]