Abstract

Background

Live donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) remains underutilized, partly due to the challenges many patients face in asking someone to donate. Actual and perceived kidney transplantation (KT) knowledge are potentially modifiable factors that may influence this process. Therefore, we sought to explore the relationships between these constructs and the pursuit of LDKT.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of transplant candidates at our center to assess actual KT knowledge (5 point assessment) and perceived KT knowledge (5 point Likert scale, collapsed empirically to 4 points); we also asked candidates if they had previously asked someone to donate. Associations between participant characteristics and having asked someone to donate were quantified using modified Poisson regression.

Results

Of 307 participants, 45.4% were female, 56.4% were non-white race, and 44.6% had previously asked someone to donate. In an adjusted model that included both actual and perceived knowledge, each unit increase in perceived knowledge was associated with 1.21-fold (95% CI: 1.03–1.43, p=0.02) higher likelihood of having asked someone to donate, whereas there was no statistically significant association with actual knowledge (RR=1.08 per unit increase, 95%CI: 0.99–1.18, p=0.10). A conditional forest analysis confirmed the importance of perceived but not actual knowledge in predicting the outcome.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that perceived KT knowledge is more important to a patient's pursuit of LDKT than actual knowledge. Educational interventions that seek to increase patient KT knowledge should also focus on increasing confidence about this knowledge.

Keywords: end-stage renal disease, kidney donation, kidney transplantation

INTRODUCTION

Nearly one quarter of the U.S. general population reports willingness to be a live organ donor (1), yet only about 6,000 live donor kidney transplant (LDKT) procedures are performed in the U.S. each year (2). We have hypothesized that the discrepancy between potential and actual LDKT is partly due to the challenges patients face in asking someone to donate, such as reluctance to discuss their illness with potential donors (3–5).

While many factors, including gender, race, and education level (6, 7), are likely associated with a patient’s decision to discuss their illness with others and to ask someone to consider donation, knowledge about kidney transplantation (KT) is a potentially modifiable factor that may influence this process. Many transplant candidates lack knowledge about topics related to KT, such as the benefits of LDKT versus deceased donor kidney transplantation (DDKT), the risks of donating, and how to discuss donation with a potential live donor (5, 8).

However, the relationship between this lack of knowledge and the actual pursuit of LDKT remains unclear. Some studies suggest that patients who have greater KT knowledge are more likely to pursue LDKT (9), that transplant candidates who do pursue LDKT tend to report that they are more informed about the topic (8, 10), and that racial disparities in pursuit of LDKT may be partially explained by differences in knowledge (9). Other studies, however, do not suggest a significant relationship between knowledge and propensity to discuss or pursue LDKT (6, 7, 11). Importantly, all of these studies were limited to the examination of objective measures of knowledge. However, perceived or subjective knowledge is separate from actual or objective knowledge, and its distinct impact on behavior has been highlighted in other areas, including the study of consumer behaviors and voluntary human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing (12, 13). We hypothesized that perceived knowledge might independently impact the pursuit of LDKT through, perhaps, its influence on patient self-efficacy and that the role of perceived knowledge might be stronger than that of actual knowledge.

To better understand the process of pursuing LDKT, the goals of our study were 1) to measure patients’ actual knowledge about KT, 2) to measure patients’ perceived knowledge about KT, 3) to explore the roles of actual and perceived knowledge in having asked someone to donate, and 4) to determine the relative importance of actual and perceived knowledge in having asked someone to donate.

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Of the 307 participants, 45.4% were female, 56.4% were non-white race, 40.1% were currently working, 45.2% had high school or less as their highest level of education, and 67.5% were married or in a relationship. At the time of the survey, 76.5% of participants were on dialysis, and 86.3% were on the DDKT waitlist (Table 2).

Table 2.

Overall patient characteristics

| Patient characteristics | % (n=307) |

|---|---|

| Female | 45.4 |

| Non-white race | 56.4 |

| Married/in a relationship | 67.5 |

| Children (any) | 69.4 |

| Working | 40.1 |

| Household annual income | |

| <$20,000 | 22.9 |

| $20,000–49,999 | 23.3 |

| $50,000–74,999 | 20.5 |

| ≥$75,000 | 33.3 |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 45.2 |

| Post-secondary education | 54.9 |

| Time on dialysis | |

| None | 23.5 |

| <1 year | 14.0 |

| 1–3 years | 23.8 |

| >3 years | 38.8 |

| Time on a waitlist | |

| Not listed | 13.7 |

| <1 year | 26.7 |

| 1–3 years | 37.7 |

| >3 years | 22.0 |

| Social Support Score, median [IQR] | 42.0 (35.0,47.0) |

| Usually go to the doctor with someone | 55.4 |

| Registered as an organ donor | 44.2 |

| Know someone who has donated an organ | 38.0 |

| Know potential organ donors | 51.3 |

| Previously received live kidney donor offer | 70.6 |

| Comfortable using computers, email, and the internet | 74.8 |

Knowledge about Kidney Transplantation

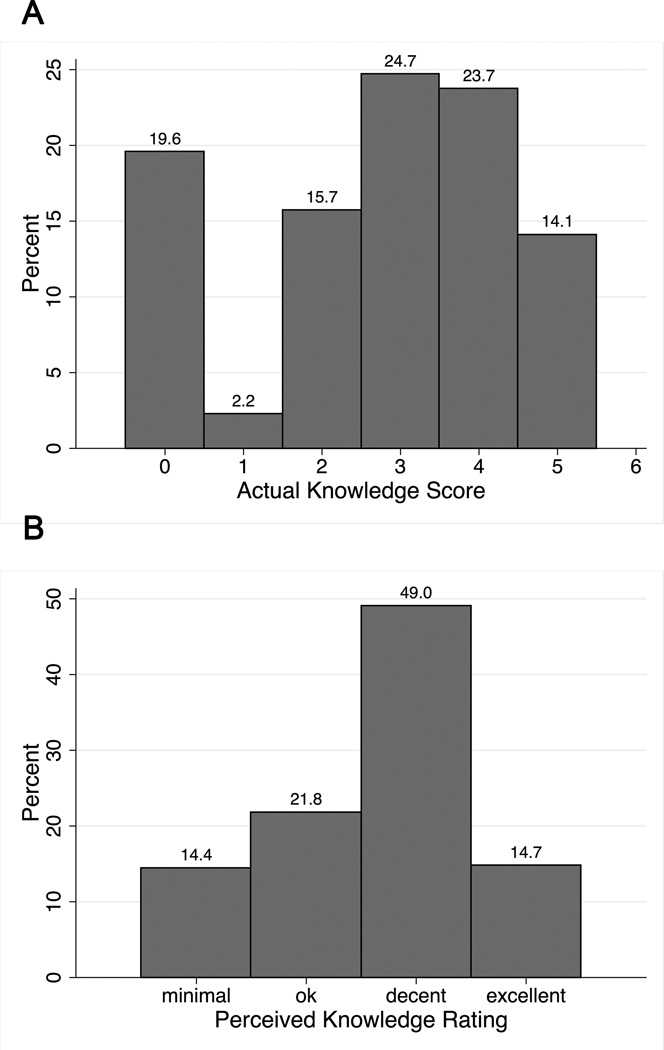

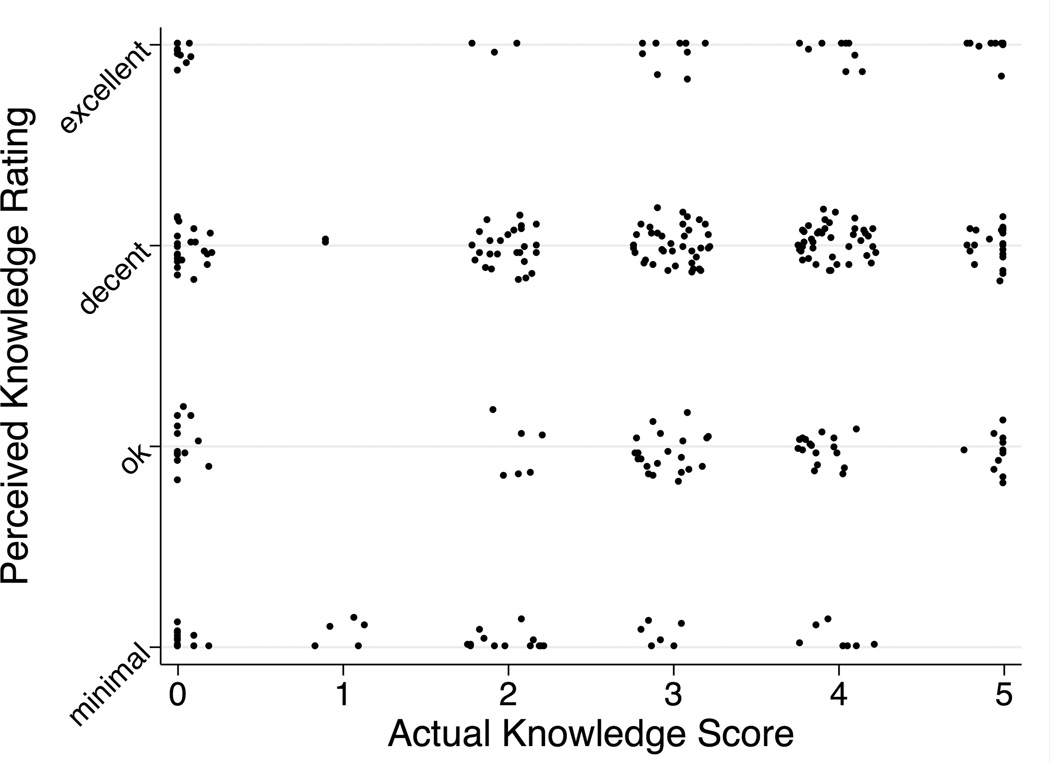

Actual knowledge appeared somewhat bimodal in distribution, whereas perceived knowledge had a pseudonormal distribution (Figure 1). Actual knowledge score and perceived knowledge rating were moderately correlated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.19 and Spearman’s correlation coefficient=0.18) (Figure 2); each one unit increase in actual knowledge score was associated with 0.35 (95% CI: 0.15 to 0.55, p=0.001) unit increase in perceived knowledge.

Figure 1.

Distributions of (A) actual knowledge score and (B) perceived knowledge rating

Panel A: The y-axis represents the percent of participants with each actual knowledge score. Panel B: The y-axis represents the percent of participants with each perceived knowledge rating.

Figure 2.

Relationship between actual knowledge score and perceived knowledge rating

A scatterplot of actual knowledge score and perceived knowledge rating shows moderate correlation between the two (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.19 and Spearman correlation coefficient=0.18).

Association of Knowledge with Having Asked Someone to Donate

At the time of the survey, 44.6% of participants had previously asked someone to donate. In models that included both actual and perceived knowledge (and also adjusted for sex, race, education, time on dialysis, time on a waitlist, whether a participant was registered as an organ donor, and whether the participant knew someone who had donated an organ), each unit increase in perceived knowledge was associated with 1.21-fold (95% CI: 1.03–1.43, p=0.02) higher likelihood of having asked someone to donate. Therefore, a participant who rated their KT knowledge as excellent would be 1.77–fold (i.e. 1.21^3) more likely to have asked someone to donate than someone who had rated their KT knowledge as minimal or unsure. In contrast, there was no statistically significant association between actual knowledge and having asked someone to donate (RR=1.08 per unit increase, 95%CI: 0.99–1.18, p=0.10) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations between knowledge and having asked someone to donate

| RR of asking someone to donate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Parsimonious | |

| Actual Knowledge | 1.09 (1.00–1.18) | 1.08 (0.99–1.18)b | 1.06 (0.98–1.15)d |

| Perceived Knowledge | 1.23 (1.07–1.42) | 1.21 (1.03–1.43)c | 1.22 (1.04–1.42)e |

RR=relative risk

Adjusted for sex, race, education, time on dialysis, time on a waitlist, registered as an organ donor, know someone who has donated an organ

Also adjusted for perceived knowledge rating. The interpretation of the RR is for each one unit increase in actual knowledge score.

Also adjusted for actual knowledge score. The interpretation of the RR is for each one unit increase in perceived knowledge rating.

Adjusted for perceived knowledge, race, registered as an organ donor, know someone who has donated an organ. The interpretation of the RR is for each one unit increase in actual knowledge score.

Adjusted for actual knowledge score, race, registered as an organ donor, know someone who has donated an organ. The interpretation of the RR is for each one unit increase in perceived knowledge rating.

Relative Importance of Actual and Perceived Knowledge

In the conditional forest (CF) analysis, only 5 factors contributed predictive power to the model: the most important variable was perceived knowledge, followed by knowing someone who had donated an organ, being registered as an organ donor, being waitlisted, and education level. In other words, when considering all variables collected in our study, perceived knowledge was most associated with having asked someone to donate and was at least 1.63 times more important than the second most important variable (knowing someone who had donated an organ). In contrast, actual knowledge did not contribute any predictive power whatsoever, confirming the findings of our regression model.

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional survey of 307 KT candidates that uniquely explored objective (actual) and subjective (perceived) knowledge separately, higher perception of knowledge about KT was most strongly associated with having asked someone to donate. After adjusting for a number of demographic, socioeconomic, and medical factors, each unit increase in perceived knowledge was associated with 1.21-fold (95% CI: 1.03–1.43, p=0.02) higher likelihood of having asked someone to donate, whereas there was no statistically significant association with actual knowledge (RR=1.08 per unit increase, 95%CI: 0.99–1.18, p=0.10). Furthermore, a CF analysis confirmed the importance of perceived but not actual knowledge in predicting the outcome.

Our study provides additional information about the relationship between actual KT knowledge and the pursuit of live donation, a relationship that has remained elusive given conflicting findings in previous studies. In particular, we observed an association between actual knowledge and having asked someone to donate in an unadjusted model, but this association was attenuated after adjusting for confounders, including perceived knowledge. Our study also expands on previous studies of actual KT knowledge and the pursuit of LDKT by adding a subjective knowledge component (8, 10).

Our findings of the independent importance of perceived knowledge in pursuing LDKT are novel to the field of kidney transplantation, but consistent with the influence of perceived knowledge on behavior in other areas. For example, perceived knowledge about acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and HIV transmission has been shown to be more strongly associated with increased voluntary HIV testing than actual knowledge about AIDS (13). Similarly, in market environments, perceived knowledge has been shown to have a greater impact on some consumer behaviors than actual knowledge (12). Mechanistically, our findings are consistent with recent suggestions by Reese et al. (2009) that a person’s belief that he or she is capable of accomplishing a goal is associated with pursuit of LDKT (11). Knowledge perception might increase pursuit of LDKT by promoting patient self-efficacy (13). Therefore, self-efficacy may mediate the relationship between perception of knowledge and asking someone to donate.

Furthermore, our findings might inform future educational interventions aimed at promoting LDKT. Several studies have demonstrated that educational interventions result in increased LDKT and reduced racial disparities in LDKT rates (8, 14–19), presumably by increasing knowledge about transplantation. Still, the exact mechanism for this is unknown, and our results suggest that the mechanism may be through increasing patient perception of knowledge rather than actual knowledge. While most of this prior research assessed knowledge objectively and found an association between increased knowledge and pursuit of LDKT (8), this effect may be driven, at least in part, by increases in perceived knowledge. Although we found very little correlation between actual and perceived knowledge, the relationship between perceived knowledge and actual knowledge may be different for patients who do and do not participate in an intervention, as the act of participating may increase both perceived and actual knowledge simultaneously. This has not yet been studied and is a future area of research.

The main strength of our study is the novel measurement of both objective and subjective measures of KT knowledge. Limitations include a cross-sectional design, which does not allow causal inference, and a single-center population, which may not be generalizable to candidates at all transplant centers.

In conclusion, perceived, not actual, knowledge about KT was independently associated with whether or not a transplant candidate had previously asked someone to donate. Our results may have important implications for future interventions aimed at promoting LDKT, as increasing patient confidence about their KT knowledge may help empower them to pursue LDKT. The relationship between perceived KT knowledge and pursuit of LDKT, as well as potential mediators of the relationship, should be further explored.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Population and Survey Administration

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 307 persons with end-stage renal disease who were either on the Johns Hopkins Hospital (JHH) DDKT waitlist as of June 2011 (retrospectively contacted) or subsequently referred for transplantation (June through October 2011) (prospectively recruited). To participate, transplant candidates needed to be at least 18 years of age and English-speaking. The survey was administered in person during the transplant evaluation (20.2%) or to patients already on the JHH waitlist via postal mail (68.7%), e-mail (8.8%), or telephone (2.3%). The outcome of having asked someone to donate a kidney was not sensitive to survey modality or cohort (p=0.3). All participants provided informed consent, and all study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board.

Participant Characteristics Ascertainment

Patient characteristics at enrollment were ascertained by self-report, including basic demographics (sex, race, marital status, and number of children), socioeconomic status (education level, employment, and household annual income), and dialysis-related characteristics (time on dialysis and time on a waitlist). Social support was measured using The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (20) and augmented by asking participants if they usually attended doctors’ appointments alone or with someone else. Familiarity with organ donation was determined by asking participants if they were registered as an organ donor, knew someone who had donated an organ, knew anyone who could potentially donate a kidney to them (7), and/or had been offered a kidney previously by a live donor (7). Ability to use technology to gain KT knowledge and to communicate with others regarding organ donation was determined by asking participants if they were comfortable using computers, email, and the internet. Finally, the outcome was assessed by asking participants if they had ever asked someone to be a live kidney donor.

Knowledge about Kidney Transplantation

Actual knowledge was quantified as the sum of the correct answers to 5 multiple-choice and true/false questions adapted from a previously validated KT knowledge survey (Table 1) (7). Sensitivity analyses in which the number of correct responses was collapsed into categories were performed, but because we found no appreciable change in model estimates or inferences, actual knowledge score was modeled using the 5 point sum. Perceived knowledge was measured by asking participants to rate their current KT knowledge on a 5-point scale (unsure, minimal, ok, decent, excellent). Participants who rated their perceived KT knowledge as “unsure” were similar to those who rated their perceived KT knowledge as “minimal” in terms of both patient characteristics and outcomes; as such, these two categories were collapsed into one “minimal” category for statistical analysis. The degree of correlation between actual and perceived knowledge was quantified using Pearson’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients; the relationship between actual and perceived knowledge was modeled using linear regression.

Table 1.

Items used to assess actual knowledge about kidney transplantationa

| Items | Response Choices |

|---|---|

| On average, patients who receive a kidney transplant: | - live longer than patients who remain on dialysisb |

| - live as long as patients on dialysis | |

| - live less long than patients on dialysis | |

| On average, a transplanted kidney from a living donor will: | - last longer than a kidney from a donor who has diedb |

| - last the same amount of time as a kidney from a donor who has died | |

| - last less time than a kidney from a donor who has died | |

| After the surgery for kidney donation, a living kidney donor | - will be likely to return home about 2–3 days after surgeryb |

| -will be likely to return home 5–7 days after surgery | |

| - will be likely to return home 2 weeks after surgery | |

| - will be likely to return home 3 weeks after surgery | |

| An acceptable living kidney donor must have the same blood type as the recipient | True Falseb |

| A person over sixty cannot be a living kidney donor | True Falseb |

Adapted from Reese et al. (2008) (7)

Correct response

Association of Knowledge with Having Asked Someone to Donate

Associations between participant characteristics, including actual and perceived KT knowledge, and having asked someone to donate were explored in univariate and multivariable models using modified Poisson regression to estimate relative risk, as previously described (21, 22). Two models examining the relationship of actual and perceived knowledge with having asked someone to donate (one combining statistical significance and a priori biological rationale and one strictly seeking optimal parsimony by empirically minimizing the Akaike Information Criterion) were fit to ensure that inferences were not sensitive to covariate selection.

Relative Importance of Actual and Perceived Knowledge

To determine the relative contributions of the factors in the model, we conducted a CF analysis. A CF analysis determines the importance of various factors in predicting the outcome by using a partial dependence plot that shows how the outcome changes when the factor changes (23). In other words, if the factor is not important, then changing the values of the factor will not reduce the prediction accuracy. The CF approach is similar to that used in a random forest approach to determine variable importance; however, CF is based on unbiased conditional inference trees (24, 25). Therefore, the results are less likely to be biased, even with correlated predictors. This was particularly relevant in our effort to determine the relative importance of perceived and actual KT knowledge in predicting if a patient had ever asked someone to be a live donor.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA 12.1/SE (College Station, Texas) and R 2.14 (26).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We sincerely thank the study participants and the staff at the Johns Hopkins University Comprehensive Transplant Center. This study was supported by R21AG034523. Megan Salter was supported by T32AG000247 from the National Institute on Aging. A preliminary report of this study was presented in June 2012 at the American Transplant Congress in Boston, Massachusetts.

ABBREVIATIONS

- AIDS

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- CF

Conditional forest

- DDKT

Deceased donor kidney transplantation

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- JHH

Johns Hopkins Hospital

- KT

Kidney transplantation

- LDKT

Live donor kidney transplantation

- RR

Relative risk

Footnotes

Natasha Gupta: participated in research design, performance of the research, data analysis, and writing of the paper; no conflict of interest. Megan L. Salter: participated in research design, performance of the research, data analysis, and writing of the paper; supported by T32AG000247 from the National Institute on Aging; no conflict of interest. Jacqueline M. Garonzik-Wang: participated in research design and writing of the paper; no conflict of interest. Peter P. Reese: participated in research design; no conflict of interest. Corey E. Wickliffe: participated in writing of the paper; no conflict of interest. Nabil N. Dagher: participated in performance of the research; no conflict of interest. Niraj M. Desai: participated in performance of the research; no conflict of interest. Dorry L. Segev: participated in research design, data analysis, and writing of the paper; supported by R21AG034523; no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.National Kidney Foundation. [cited 2013 June 10, 2013];Survey Shows Public Says "Yes" to Strangers. 2000 Available from: http://www.kidney.org/news/newsroom/newsitemArchive.cfm?id=83.

- 2.Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. [Accessed June 10, 2013];National Kidney Dataset: Transplants by Donor Type, January 1, 1988-May 31, 2013. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/latestData/rptData.asp. In. 05/31/2013.

- 3.Barnieh L, McLaughlin K, Manns BJ, Klarenbach S, Yilmaz S, Taub K, et al. Evaluation of an education intervention to increase the pursuit of living kidney donation: a randomized controlled trial. Prog Transplant. 2011;21(1):36–42. doi: 10.1177/152692481102100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kranenburg LW, Richards M, Zuidema WC, Weimar W, Hilhorst MT, JN IJ, et al. Avoiding the issue: patients' (non)communication with potential living kidney donors. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;74(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waterman AD, Stanley SL, Covelli T, Hazel E, Hong BA, Brennan DC. Living donation decision making: recipients' concerns and educational needs. Prog Transplant. 2006;16(1):17–23. doi: 10.1177/152692480601600105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. Patients' willingness to talk to others about living kidney donation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18(1):25–31. doi: 10.1177/152692480801800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reese PP, Shea JA, Berns JS, Simon MK, Joffe MM, Bloom RD, et al. Recruitment of live donors by candidates for kidney transplantation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(4):1152–1159. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03660807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodrigue JR, Cornell DL, Lin JK, Kaplan B, Howard RJ. Increasing live donor kidney transplantation: a randomized controlled trial of a home-based educational intervention. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(2):394–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;8(6):995–1002. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08880812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kranenburg LW, Zuidema WC, Weimar W, Hilhorst MT, Ijzermans JN, Passchier J, et al. Psychological barriers for living kidney donation: how to inform the potential donors? Transplantation. 2007;84(8):965–971. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000284981.83557.dc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reese PP, Shea JA, Bloom RD, Berns JS, Grossman R, Joffe M, et al. Predictors of having a potential live donor: a prospective cohort study of kidney transplant candidates. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(12):2792–2799. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn LR, Goldsmith RE. A Short, Reliable Measure of Subjective Knowledge. Journal of Business Research. 1999;46(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips KA. Subjective knowledge of AIDS and use of HIV testing. Am J Public Health. 1993;83(10):1460–1462. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.10.1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ephraim PL, Powe NR, Rabb H, Ameling J, Auguste P, Lewis-Boyer L, et al. The providing resources to enhance African American patients' readiness to make decisions about kidney disease (PREPARED) study: protocol of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Nephrol. 2012;13:135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-13-135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Waterman AD, Rodrigue JR, Purnell TS, Ladin K, Boulware LE. Addressing racial and ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30(1):90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garonzik-Wang JM, Berger JC, Ros RL, Kucirka LM, Deshpande NA, Boyarsky BJ, et al. Live donor champion: finding live kidney donors by separating the advocate from the patient. Transplantation. 2012;93(11):1147–1150. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31824e75a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DePasquale N, Ephraim PL, Ameling J, Lewis-Boyer L, Crews DC, Greer RC, et al. Selecting renal replacement therapies: what do African American and non-African American patients and their families think others should know? A mixed methods study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheu J, Ephraim PL, Powe NR, Rabb H, Senga M, Evans KE, et al. African American and non- African American patients' and families' decision making about renal replacement therapies. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(7):997–1006. doi: 10.1177/1049732312443427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Melancon JK, McGuire R, Bonhage B, et al. Protocol of a randomized controlled trial of culturally sensitive interventions to improve African Americans' and non-African Americans' early, shared, and informed consideration of live kidney transplantation: the Talking About Live Kidney Donation (TALK) Study. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-12-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Behrens T, Taeger D, Wellmann J, Keil U. Different methods to calculate effect estimates in cross-sectional studies. A comparison between prevalence odds ratio and prevalence ratio. Methods Inf Med. 2004;43(5):505–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strobl C, Boulesteix AL, Kneib T, Augustin T, Zeileis A. Conditional variable importance for random forests. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:307. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strobl C, Boulesteix AL, Zeileis A, Hothorn T. Bias in random forest variable importance measures: illustrations, sources and a solution. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strobl C, Zeileis A. Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Computational Statistics. Portugal: 2008. Danger: High Power! - Exploring the Statistical Properties of a Test for Random Forest Variable Importance. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Computing RFfS, editor. R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. Austria: Vienna; 2013. [Google Scholar]