Abstract

Background

The risks and benefits of metformin use in cirrhotic patients with diabetes are debated. Although data on a protective effect of metformin against liver cancer development have been reported, metformin is frequently discontinued once cirrhosis is diagnosed due to concerns about an increased risk of adverse effects of metformin in patients with liver impairment. This study investigated whether continuation of metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis improves survival of patients with diabetes.

Methods

Diabetic patients diagnosed with cirrhosis between 2000 and 2010 who were on metformin at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis were identified (n=250). Data were retrospectively abstracted from the medical record. Survival of patients who continued versus discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis was compared using the log-rank test. The hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated using Cox Proportional Hazards analysis.

Results

172 patients continued metformin while 78 discontinued metformin. Patients who continued metformin had a significantly longer median survival than those who discontinued metformin (11.8 vs. 5.6 years overall, P < 0.0001; 11.8 vs. 6.0 years for Child A patients, P = 0.006; and 7.7 vs. 3.5 years for Child B/C patients, P = 0.04, respectively). After adjusting for other variables, continuation of metformin remained an independent predictor of better survival with a HR of 0.43 (95%CI: 0.24-0.78, P = 0.005). No patients developed metformin-associated lactic acidosis during follow-up.

Conclusion

Continuation of metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis reduced the risk of death by 57%. Metformin should therefore be continued in diabetic patients with cirrhosis if there is no specific contraindication.

Keywords: Chronic liver disease, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Antidiabetic drug, Lactic acidosis, Metformin-associated lactic acidosis

Introduction

Cirrhosis is responsible for over 29,000 deaths annually in the U.S. and one million deaths annually worldwide, making it the 12th leading cause of mortality both in the U.S. and globally.1, 2 The prevalence of type 2 diabetes in cirrhotic patients has been reported as 37%, five times greater than in those without cirrhosis.3 Cirrhotic patients with diabetes have a greater risk of liver-related complications and death than cirrhotic patients without diabetes.4-9 Similarly, the risk of death from cirrhosis among diabetic patients was greater than in the general population, with a standardized mortality ratio of 2.5, which is even higher than the mortality ratio of 1.3 conferred by cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes.10 Therefore, it is important to improve cirrhosis-related mortality in diabetic patients.

Metformin, a commonly prescribed oral hypoglycemic agent, has a protective effect against cancer development and cancer mortality in type 2 diabetic patients.11-13 Metformin use was associated with a decreased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in diabetic patients with chronic liver disease.14 Metformin was also independently associated with a reduction in HCC incidence and liver-related death in patients with type 2 diabetes and hepatitis C virus (HCV) induced cirrhosis.15 Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease appears to partially mediate an increased risk of liver-related death among patients with diabetes. The presence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increased deaths in diabetic patients, with a hazard ratio of 2.2, with 19% of deaths being liver-related.16 Metformin prevented and reversed steatosis and inflammation in a non-diabetic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 17 and improved liver histology and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels in patients with NASH.18, 19

Due to theoretical concerns about the increased risk of lactic acidosis in diabetic patients with chronic liver disease, many clinicians are reluctant to prescribe metformin for diabetic patients with chronic liver disease and some recommend discontinuation of metformin after the diagnosis of cirrhosis. However, the evidence that metformin induces liver injury is weak.20 The incidence of lactic acidosis in diabetic patients treated with metformin is low, approximately 0.03 to 0.5 cases per 1,000 patient-years, and the incidence of lactic acidosis among diabetic patients who take metformin does not differ from the incidence in diabetic patients not receiving metformin.21-23 In addition, the published reports of lactic acidosis in patients with liver disease are largely restricted to case reports of cirrhotic patients who were actively drinking alcohol.24 Thus, these patients may not represent the general population with cirrhosis and diabetes.

Given the potential beneficial effects of metformin on liver inflammation and carcinogenesis, we hypothesized that continuation of metformin use after the diagnosis of cirrhosis would improve the survival outcome of diabetic patients. The primary aim of our study was to assess the survival difference between diabetic patients who continued taking metformin versus those who discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis. We also investigated other factors determining survival outcomes in cirrhotic patients with diabetes.

Methods

Patients

All diabetic patients diagnosed with cirrhosis between January 1, 2000 and December 31, 2010 who were on metformin at cirrhosis diagnosis were included in this study (n=250). Patients were categorized into 2 groups, i.e. 1) those who continued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis; and 2) those who discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis. Continuation of metformin use was defined as taking metformin for at least 3 months after cirrhosis diagnosis; and discontinuation of metformin use was defined as cessation of metformin within a 3-month period after the diagnosis of cirrhosis. The 3-month period was arbitrarily chosen as a cut-off to allow time for health care providers to decide whether to continue or discontinue metformin. Metformin was typically discontinued within this time frame after cirrhosis diagnosis in our cohort.

The diagnosis of cirrhosis was ascertained by histology (n=124) and/or by clinical features, namely portal hypertension, morphologic characteristics consistent with cirrhosis in cross-sectional radiologic images (small sized nodular liver ± caudate lobe hypertrophy, portal hypertension indicated by the presence of collateral vessels, varices, and/or splenomegaly), and/or thrombocytopenia (platelet count <150K). Diabetes was defined by a physician note, self-reported medical history or taking anti-diabetic medication or the American Diabetes Association criteria (fasting blood glucose ≥126, or glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) >6.5% or random glucose of 200 mg/dl with presence of symptoms). Exclusion criteria were as follows: 1) a history of malignancy except for non-melanoma skin cancer at cirrhosis diagnosis; 2) incomplete clinical information; 3) age <18 years; 4) discontinuation of metformin before cirrhosis diagnosis; or 5) initiation of metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis. The study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Clinical Information

Demographics, clinical information, and laboratory results at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis were abstracted from the electronic medical record, including age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), etiology of cirrhosis, liver biochemistries, HbA1c and plasma glucose level, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and Child-Pugh score, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), the last follow up date with vital status, and cause of death. The use of metformin and reasons for stopping metformin were ascertained from the medication list and physician’s notes. Concurrent history of statin use was also abstracted.

Obesity was defined as BMI ≥30 kg/m2. The etiology of cirrhosis was classified as NASH, alcoholic liver disease, hepatitis B virus (HBV) and HCV infection and others, (i.e. primary biliary cirrhosis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hereditary hemochromatosis, Wilson's disease, alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, and cardiac cirrhosis). NASH was considered a cause of cirrhosis if there was a documented history of NASH or radiographic or histologic evidence of fatty infiltration in the absence of a history of significant alcohol use. HBV infection was defined as a positive hepatitis B surface antigen, and HCV infection was defined as a positive HCV RNA. A diagnosis of HBV or HCV infection in the physician's note was accepted as a diagnosis of viral infection. Alcoholic cirrhosis was defined as having a documented history of alcoholic liver disease, alcohol abuse or dependence or having alcohol greater than 140 and 70 g/week in men and women, respectively and without other specific causes of cirrhosis.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients who continued metformin vs. discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis were compared using the Student's t test for continuous variables and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. Survival of patients in both groups was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Survival time was calculated from the date of cirrhosis diagnosis to the date of last follow up or death. Associations between predictor variables and survival were determined by hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) calculated using Cox Proportional Hazards regression. Variables with P < 0.1 in the univariate model were included in the multivariate model. MELD score was included in the multivariate analysis to adjust for the potential confounding effect of liver function. Individual components of the MELD score were not included in the multivariate analysis.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

Of the total of 250 diabetic patients who were on metformin at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis, 142 (56.8%) patients were male with a mean age (± SD) of 61.2 ± 9.8 years; 181 (73.3%) had Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis. The etiologies of cirrhosis were NASH (56.8%), alcoholic liver disease (11.6%), HCV (12.0%), HBV (2.4%), others (5.6%) and unknown (11.6%). Of the 250 diabetic patients on metformin at the time of cirrhosis diagnosis, 172 (68.8%) continued metformin while 78 (31.2%) discontinued metformin. Reasons for discontinuation of metformin included diagnosis of cirrhosis (n=61; 78% of patients who discontinued metformin); uncontrolled plasma glucose (n=5); elevated serum creatinine (n=3); diarrhea (n=2); well controlled plasma glucose level (n=2); switching to insulin therapy (n=2); unstated reasons during hospitalization (n=2); and heart disease (n=1).

Table 1 summarizes patient demographics and baseline characteristics of the continued and discontinued metformin groups. Age, gender, ethnicity, etiology of cirrhosis, BMI, ALT, prothrombin time (PT), international normalized ratio (INR), AFP, and severity of diabetes as determined by HbA1c levels and fasting plasma glucose levels, were not significantly different between the two groups. Not surprisingly, the continued metformin group had significantly better liver function, demonstrated by a higher proportion of Child A cirrhotic patients, and a lower MELD score (P = 0.01 and < 0.001, respectively), thus the potential effect of MELD score on outcome was assessed in subsequent analyses. Given that both MELD score and Child-Pugh classification reflect severity of liver impairment, we selected MELD score in the multivariate analysis as MELD score better correlates with severity of liver impairment than the Child-Pugh classification.

Table 1. Characteristics of cirrhotic patients with diabetes.

| Variables | Continued metformin n=172 |

Discontinued metformin n=78 |

P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age*, y | 61.7 ± 9.8 | 60.2 ± 9.9 | 0.24 |

| (range) | (38-87) | (36-81) | |

| Male, n (%) | 100 (58.1) | 42 (53.9) | 0.52 |

| Race, n (%) | 0.96 | ||

| White | 150 (87.2) | 69 (88.5) | |

| Non-white | 17 (9.9) | 8 (10.3) | |

| Unknown | 5 (3.0) | 1 (1.3) | |

| BMI, kg/m2† | 34.3 (20.7-63.5) | 34.8 (20.1-72.7) | 0.55 |

| Obesity, n (%) | 112 (65.5) | 54 (69.2) | 0.56 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis, n (%) | 0.80 | ||

| HBV | 6 (3.5) | 0 | |

| HCV | 16 (9.3) | 14 (17.9) | |

| Alcoholic liver disease | 19 (11.0) | 10 (12.8) | |

| NASH | 98 (57.0) | 44 (56.4) | |

| Others | 8 (4.7) | 6 (7.7) | |

| Unknown | 25 (14.5) | 4 (5.1) | |

| MELD score* | 8.9 ± 3.0 | 10.6 ± 4.4 | <0.001 |

| Child-Pugh class§, n (%) | 0.01 | ||

| A | 133 (78.7) | 48 (61.5) | |

| B | 33 (19.5) | 28 (35.9) | |

| C | 3 (1.8) | 2 (2.6) | |

| Laboratory results†, | |||

| AST level, IU/L | 49 (36-73) | 63 (44-82) | 0.02 |

| ALT level, IU/L | 43 (32-71) | 57 (32-84) | 0.08 |

| Total Bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.6-1.4) | 1.1 (0.6-1.8) | 0.04 |

| Albumin, g/dL | 3.9 (3.5-4.2) | 3.6 (3.4-4.1) | 0.01 |

| Platelets, ×109/L | 126 (90-192) | 120 (77-153) | 0.08 |

| INR | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 0.12 |

| PT, second | 10.7 (9.8-11.4) | 10.9 (10.1-12.0) | 0.05 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 0.01 |

| Fasting plasma glucose, mg/dL | 134 (115-164) | 129 (108-190) | 0.41 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.5 (5.7-7.2) | 6.7 (5.7-7.8) | 0.14 |

| AFP, ng/mL | 4.6 (3.0-7.1) | 4.7 (3.3-7.0) | 0.81 |

mean ± SD,

median ± interquartile range;

3 patients had missing information for Child-Pugh class in the continued metformin group.

It has been reported that other medications such as statins may also benefit cirrhotic patients. In an attempt to determine the impact of statins on survival, we compared the concurrent or previous use of statins in the cohort patients. The numbers of patients with a history of statin use who continued vs. discontinued metformin were 29 (16.9%) vs. 9 (11.5%) respectively, P=0.27. Thus, no significant difference was found in the frequency of statin use between the two groups.

Survival of patients who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis

The median survival of patients who continued metformin was significantly greater than that of patients who discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis (11.6 vs. 5.6 years, P < 0.0001) (Figure 1). Five-year and 10-year survival rates of patients who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin were 77.5% vs. 53.1%; and 55.2% vs. 30.7%, respectively. The median (range) time of metformin use in the continued metformin group was 26.8 (3.1-151.1) months. Therefore, most patients who continued metformin received metformin for substantially longer than 3 months, with 121 of the 172 (70.3%) receiving metformin for over 1 year (Supplemental Figure 1). In a sensitivity analysis to confirm that the 3 month cut-off did not overestimate the benefit of continuation of metformin, we compared the survival of the diabetic patients who continued (n=121) vs. discontinued metformin (n=129) 1 year after cirrhosis diagnosis. The median survival of the patients who continued metformin remained significantly greater than that of the patients who discontinued metformin within 1 year after cirrhosis diagnosis (11.8 vs. 6.0 years, P < 0.0001) (Supplemental Figure 2).

Figure 1. Survival of 250 diabetic patients who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis.

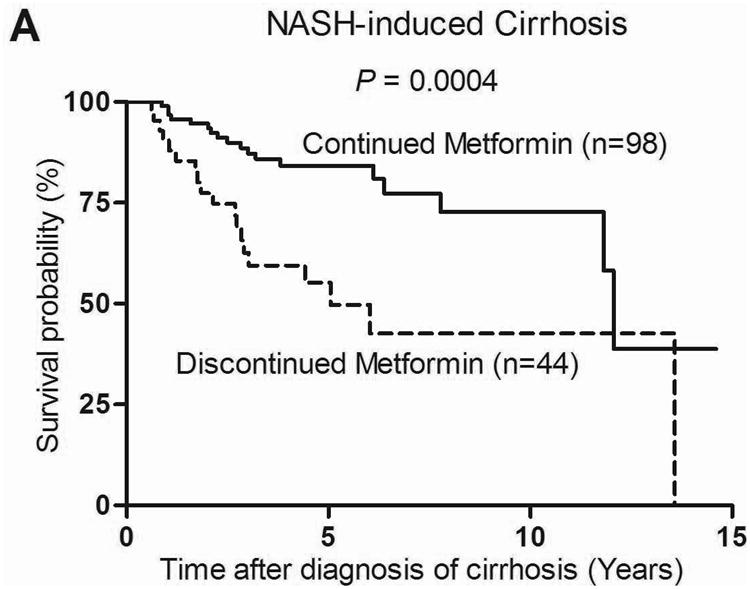

The benefit of continuation of metformin on survival was found regardless of severity of cirrhosis as defined by Child-Pugh classification. Of the 181 Child A cirrhotic patients, those who continued metformin (n=133) had a significantly greater median survival than those who discontinued metformin (n=48) (11.8 vs. 6.0 years, P = 0.006) with a HR of death of 0.47 (95% CI: 0.27-0.82, P = 0.009) (Figure 2a). Similarly, in a pooled analysis, Child B (n=61) and Child C (n=5) cirrhotic patients who continued metformin (n=36) had a significantly greater median survival than those who discontinued metformin (n=30) (7.7 vs. 3.5 years, P = 0.04) with a HR of 0.46 (95% CI: 0.21-0.98, P = 0.04) (Figure 2b).

Figure 2. Survival of Child-Pugh class A (n=181) (A) and Child-Pugh class B/C (n=66) (B) cirrhotic patients with diabetes who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin.

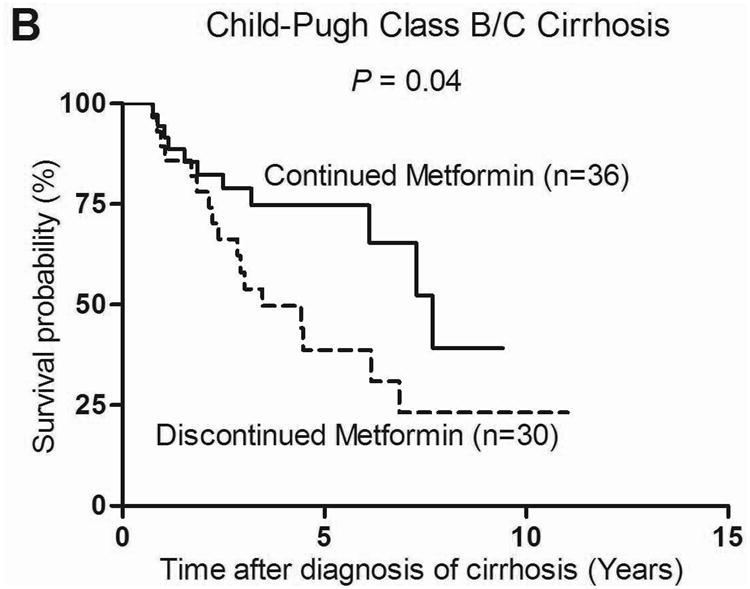

When patients were categorized based on the etiology of cirrhosis, the beneficial effect of metformin on survival was observed only in the NASH-related cirrhosis group. The median survival of patients with NASH-related cirrhosis who continued metformin (n=98) vs. discontinued metformin (n=44) was 12.1 years vs. 5.1 years, P = 0.0004 with a HR of 0.33 (95% CI 0.17-0.63; P < 0.0001) (Figure 3a). Survival of those who continued vs. those who discontinued metformin was not statistically different in the alcohol, HCV and HBV-related cirrhosis group, likely due to the small number of patients in each group 29, 30 and 6 patients respectively. Thus in order to obtain a larger number we combined patients with cirrhosis from alcohol, HCV, HBV, other and unknown etiologies into a non-NASH cirrhosis group (n=108), no significant difference was observed in survival between the continued metformin and discontinued metformin subgroups (Figure 3b).

Figure 3. Survival of 142 patients with NASH related cirrhosis (A) and 108 patients with non-NASH related cirrhosis (B) who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin.

Eighty one patients (43 of 172 (25%) in the continued metformin group and 38 of 78 (49%) in the discontinued group) died during a median (range) follow up time of 5.2 (0.6 – 14.6) years. The median durations of follow up were 4.8 (0.6 – 14.6) and 5.4 (0.6 – 13.6) years in the continued and discontinued groups, respectively. At the last follow-up visit, 129 (75%) and 40 (51%) patients in the continued and discontinued groups were alive, of whom 54 (41.9%) and 15 (37.5%) patients had been followed for at least 5 years, respectively. Of the 81 deceased patients, 39 (48%) patients had information on causes of death available in the medical record (21 and 18 in the continued and discontinued metformin groups, respectively). The causes of death included liver-related deaths (n=32; 82% of those with available cause of death information); pulmonary disease (n=3); and heart disease, renal failure, accident, and leukemia (n=1 for each).

Predictors of survival of cirrhotic patients with diabetes

Continuation of metformin use was significantly associated with better survival in cirrhotic patients with diabetes. In univariate analysis, continuation of metformin (HR: 0.43; 95% CI: 0.28-0.66; P = 0.0001) and high serum albumin level (HR: 0.53; 95% CI: 0.36-0.77; P = 0.001) were significantly associated with better survival. By contrast, every 10 years increase in age (HR: 1.59; 95% CI: 1.25-2.02; P = 0.0001), male sex (HR: 1.77; 95% CI: 1.11-2.82; P = 0.02), increased MELD score (HR: 1.08; 95% CI: 1.02-1.13; P = 0.007), log bilirubin (HR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.07-1.82; P = 0.015), serum creatinine (HR: 2.7; 95% CI: 1.51-4.87; P = 0.0009), and every 10 ng/ml increase in serum AFP (HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.09-1.17; P < 0.0001) were significantly associated with worse survival. Etiology of cirrhosis was also associated with survival; compared to the reference group with HBV-induced cirrhosis, patients with HCV, NASH or other causes of cirrhosis had HRs in the 1.3-1.5 range, while those with cirrhosis due to alcoholic liver disease had a HR of 3.8, however, none of these associations was statistically significant. Ethnicity, ALT, platelet count, INR, PT, and fasting plasma glucose were not associated with survival (Table 2).

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards analysis of variables associated with death of cirrhotic patients with diabetes.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||

| HR (95% CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Age, per 10 years | 1.59 (1.25-2.02) | 0.0001 | 1.29 (0.91-1.81) | 0.15 |

| Male | 1.77 (1.11-2.82) | 0.02 | 1.51 (0.78-2.92) | 0.22 |

| Race | ||||

| Non-white | 1.00 (reference) | |||

| White | 2.33 (0.85-6.40) | 0.10 | ||

| BMI | 0.25 (0.04-1.54) | 0.14 | ||

| Obesity | 1.35 (0.85-2.10) | 0.20 | ||

| Etiology of cirrhosis | 0.01 | 0.03 | ||

| HBV | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | ||

| HCV | 1.37 (0.17-10.77) | 0.39 (0.04-3.52) | ||

| Alcoholic liver disease | 3.86 (0.51-29.25) | 2.29 (0.29-18.27) | ||

| NASH | 1.32 (0.18-9.69) | 0.97 (0.13-7.53) | ||

| Others | 1.42 (0.16-12.77) | 0.71 (0.07-7.57) | ||

| MELD score | 1.08 (1.02-1.13) | 0.0067 | 1.01 (0.93-1.09) | 0.82 |

| Laboratory results | ||||

| AST level | 1.0 (0.996-1.004) | 0.97 | ||

| ALT level | 0.998 (0.994-1.002) | 0.41 | ||

| Loge Bilirubin | 1.39 (1.07-1.82) | 0.015 | ||

| Albumin | 0.53 (0.36-0.77) | 0.001 | 0.53 (0.28-1.01) | 0.06 |

| Platelets | 1.001 (0.998-1.004) | 0.56 | ||

| INR | 1.27 (0.54-2.98) | 0.59 | ||

| Creatinine | 2.70 (1.51-4.87) | 0.0009 | ||

| Fasting plasma glucose, | 0.998 (0.994-1.003) | 0.47 | ||

| AFP, per 10 ng/mL† | 1.13 (1.09-1.17) | <0.0001 | 1.13 (1.07-1.18) | <0.0001 |

| Continuing metformin after cirrhosis diagnosis | 0.43 (0.28-0.66) | 0.0001 | 0.43 (0.24-0.78) | 0.005 |

MELD was included in this model rather than bilirubin, INR and creatinine.

AFP of >200 ng/mL was coded as 200 ng/mL.

The benefit of metformin use on survival outcome remained significant after adjusting for other variables, i.e. age, gender, albumin, MELD score, AFP level and etiology of cirrhosis (Table 2). Continuation of metformin use was independently associated with a 57% decrease in the risk of death with a HR of 0.43 (95% CI: 0.24-0.78, P = 0.005). By contrast, every 10 ng/mL increase in AFP value was associated with a 13% increased risk for mortality (HR: 1.13; 95% CI: 1.07-1.18; P < 0.0001) (Table 2). Given that the information on AFP value was missing in 52 of 250 (20.8%) patients, we also performed another multivariate analysis excluding the AFP value and the primary finding of an association between the continuation of metformin use and survival remained unchanged (HR: 0.38, 95% CI: 0.23-0.64, P = 0.0002) (Supplemental Table 1).

Discussion

We conducted a clinic/hospital-based cohort study to determine the outcomes and safety of metformin in diabetic patients with cirrhosis. Continuation of metformin use after cirrhosis diagnosis was associated with significantly improved survival in diabetic patients, regardless of severity of liver impairment. Our data suggest that metformin is safe in diabetic patients with cirrhosis because no patients developed lactic acidosis while receiving metformin in our cohort.

In this study, metformin use was significantly associated with a 57% reduction in risk of all-cause mortality in diabetic patients with all stages of cirrhosis. Our finding suggested that metformin may prevent liver-related mortality as most patients (82%) died from liver-related diseases. The mechanism by which metformin reduces mortality in cirrhotic patients is currently unknown. Given that metformin use had a protective effect against death only in the subgroup of NASH-related cirrhotic patients; it is biologically plausible that metformin may slow progression of liver fibrosis by attenuating steatohepatitis. This hypothesis is supported by evidence from recent studies.17-19 Metformin has been demonstrated to reverse steatosis and inflammation in a mouse model with NASH; reduce hepatocellular injury and improve ALT levels in NASH patients; and significantly decrease hepatic fat, necroinflammation and fibrosis in non-diabetic NASH patients.17-19

We did not find a significant survival benefit in subgroups of patients with cirrhosis induced by HCV, HBV, or alcohol, possibly because of the small numbers of patients, or the entire group of patients with non-NASH-induced cirrhosis. Additional studies in larger cohorts are needed to determine whether metformin confers a survival benefit for diabetic patients with cirrhosis from causes other than NASH.

Baseline liver function, as indicated by MELD score and Child-Pugh classification, is known to be a strong predictor of survival in cirrhotic patients. In our study, MELD score was not associated with survival of cirrhotic patients, likely because most patients had low MELD scores. We found that a significantly higher proportion of patients continuing metformin had Child-Pugh class A cirrhosis and a lower mean MELD score than those who discontinued metformin. To determine whether baseline liver function confounds the association of metformin continuation and survival, we adjusted for the MELD score in the multivariate analysis. Metformin continuation remained a significant predictor of better survival after adjusting for the MELD score. In addition, we also categorized patients based on Child-Pugh classification and determined the effect of metformin on survival of patients with Child-Pugh class A versus Child-Pugh class B/C cirrhosis separately. There was a significant benefit of metformin continuation in both the Child-Pugh class A and Child-Pugh class B/C cirrhosis groups. This suggests that metformin can be continued in diabetic patients with compensated or decompensated cirrhosis if there is no specific contraindication.

Although the main reason for discontinuation of metformin in our cohort was the concern about an increased risk of developing lactic acidosis, no patient developed lactic acidosis or serious complications from metformin use. In fact, the incidence of lactic acidosis in diabetic patients on metformin is extremely low.21-23 Specifically, most patients who developed metformin-induced lactic acidosis had risk factors for lactic acidosis, particularly, marked renal impairment.25 Preexisting renal insufficiency and cardiac disease (e.g. heart failure) have been commonly reported as risk factors for metformin-induced lactic acidosis whereas liver impairment was rarely identified as a risk factor for lactic acidosis.25-27 Indeed, despite the widespread use of metformin, very few cases with preexisting liver impairment have been reported to develop lactic acidosis; two with cirrhosis,28 one actively drinking alcoholic cirrhotic24 and one with liver failure.25 Thus far, no studies have specifically determined the incidence of lactic acidosis in a cohort of cirrhotic patients on metformin. Interestingly, none of the Child B (n=33, 19.5%) and Child C (n=3, 1.8%) patients in our cohort experienced a life-threatening complication due to the use of metformin. Thus, our data, albeit with a small number of decompensated cirrhotic patients, suggested the safety of metformin use in cirrhotic patients without a specific contraindication.

Controlling blood sugar in diabetic patients with cirrhosis can be more challenging due to fluctuations in blood sugar levels, hypoglycemia is a particular concern of physicians when prescribing oral hypoglycemic agents. Some physicians therefore prefer insulin to avoid hypoglycemia in diabetic patients with cirrhosis. However, metformin does not cause hypoglycemia and can be used in combination with insulin without increasing the risk of hypoglycemia.

Interestingly, AFP was an independent risk factor for death of cirrhotic patients with diabetes. Given that a rising AFP value is used as a predictor of HCC development, we investigated if metformin decreased the risk of HCC development in our cohort. We did not find a significant association between continuation of metformin and reduced HCC risk (data not shown). This result was inconsistent with the study by Chen et al. which reported that metformin reduced risk of HCC development by 7% per year.13 This inconsistency may result from the limited number of patients who developed HCC in our cohort (n=10 (5.8%) in continued and 5 (6.4%) in discontinued groups), as this cohort study was powered to address the difference in survival instead of HCC incidence in the cirrhosis patients. The information on lack of apparent HCC risk reduction was provided as an underpowered secondary analysis.

The major strength of our study lies in the large cohort of cirrhotic patients with diabetes who have various causes of cirrhosis and a wide range of degrees of severity of liver impairment. To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort of unselected cirrhotic patients with diabetes in which the effect of metformin use has been investigated. We also provided data on the safety of metformin use in cirrhotic patients. This study has therefore contributed significantly to filling the knowledge gap in the debate on whether metformin can be safely prescribed to cirrhotic patients. Importantly, our study revealed the novel observation of an association between metformin use and improved survival in a cohort of cirrhotic patients with diabetes.

Our study had a number of limitations. We were not able to take into consideration the effect of dose or duration of metformin treatment on survival. Due to the retrospective study design, detailed information on use of anti-diabetic agents was not always available. Thus, we were not able to determine the minimum effective dose of metformin that resulted in improved survival of patients with cirrhosis. Metformin is the major anti-diabetic agent with a biologically plausible mechanism for improving liver function. Other medications may also benefit cirrhotic patients, however, the sample size of the study was not large enough to sustain the multivariate model that would be needed to investigate the effect of metformin and at the same time provide valid estimates of the concomitant effects of other medications. We were not able to confirm a benefit of metformin use on reducing HCC incidence due to the limited number of patients who developed HCC in our cohort. Moreover, although we adjusted for MELD score to account for the influence of more severe comorbidities in the decision to discontinue metformin, MELD score may not completely account for the effects of all possible comorbidities.

A number of research questions should be further investigated. It is worth examining the impact of metformin on survival of patients with non-NASH cirrhosis in a larger cohort. Whether initiating metformin following diagnosis of cirrhosis would improve survival of diabetic patients needs to be answered. It will also be interesting to further investigate whether metformin has an anti-fibrotic effect by slowing down progression or reversing the degree of liver fibrosis. Given that the prevalence of impaired glucose tolerance in cirrhotic patients is as high as 50-60%, it will be of interest to investigate whether metformin also improves the outcomes of cirrhotic patients with impaired glucose tolerance.

In conclusion, we report the novel observation of an association between continuation of metformin use after cirrhosis diagnosis and improved survival of diabetic patients. Our findings strongly suggest that continuation of metformin improves the survival of NASH-related cirrhotic patients with diabetes. Validation of these results in a larger cohort would support continuation of metformin use in NASH-related cirrhosis.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. The duration of metformin use after the date of cirrhosis diagnosis in the continued metformin group (n=172)

Supplemental Figure 2. Survival of 250 diabetic patients who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin within 1 year after cirrhosis diagnosis

Supplemental Table: Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards analysis of variables associated with survival of cirrhotic patients with diabetes. This model excluded AFP because 52 patients had missing AFP values

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Jennifer L. Rud for secretarial assistance.

Financial disclosure: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants CA128633 and CA165076 (to LRR); the Mayo Clinic Center for Cell Signaling in Gastroenterology (NIDDK P30DK084567); the Mayo Clinic Cancer Center (CA15083), and the Mayo Clinic Center for Translational Science Activities (NIH/NCRR CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR000135). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- AFP

alpha-fetoprotein

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- BMI

body mass index

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin

- HR

hazard ratio

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- INR

international normalized ratio

- MELD

model for end-stage liver disease

- NASH

nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- PT

prothrombin time

Footnotes

Disclosures: There is none of Conflict of Interest to declare.

References

- 1.Minino AM, Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2008. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2011;59:1–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wlazlo N, Beijers HJ, Schoon EJ, Sauerwein HP, Stehouwer CD, Bravenboer B. High prevalence of diabetes mellitus in patients with liver cirrhosis. Diabetic Medicine. 2010;27:1308–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wlazlo N, van Greevenbroek M, Curvers J, Schoon EJ, Friederich P, Twisk J, et al. Diabetes mellitus at the time of diagnosis of cirrhosis is associated with higher incidence of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, but not with increased mortality. Clinical science. 2013;125:341–8. doi: 10.1042/CS20120596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El-Serag HB, Tran T, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of chronic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:460–8. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.10.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El-Serag HB, Everhart JE. Diabetes increases the risk of acute hepatic failure. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1822–8. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Butt Z, Jadoon NA, Salaria ON, Mushtaq K, Riaz IB, Shahzad A, et al. Diabetes Mellitus and Decompensated Cirrhosis: Risk of Hepatic Encephalopathy in Different Age Groups. Journal of diabetes. 2013;5:449–55. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldt BJ, Chen W, Heathcote EJ, Wedemeyer H, Reichen J, Hofmann WP, et al. Increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2008;47:1856–62. doi: 10.1002/hep.22251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quintana JO, Garcia-Compean D, Gonzalez JA, Perez JZ, Gonzalez FJ, Espinosa LE, et al. The impact of diabetes mellitus in mortality of patients with compensated liver cirrhosis-a prospective study. Annals of hepatology. 2011;10:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Marco R, Locatelli F, Zoppini G, Verlato G, Bonora E, Muggeo M. Cause-specific mortality in type 2 diabetes. The Verona Diabetes Study Diabetes care. 1999;22:756–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.5.756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bo S, Benso A, Durazzo M, Ghigo E. Does use of metformin protect against cancer in Type 2 diabetes mellitus? Journal of endocrinological investigation. 2012;35:231–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03345423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaiteerakij R, Yang JD, Harmsen WS, Slettedahl SW, Mettler TA, Fredericksen ZS, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: association between metformin use and reduced cancer risk. Hepatology. 2013;57:648–55. doi: 10.1002/hep.26092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen HP, Shieh JJ, Chang CC, Chen TT, Lin JT, Wu MS, et al. Metformin decreases hepatocellular carcinoma risk in a dose-dependent manner: population-based and in vitro studies. Gut. 2013;62:606–15. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donadon V, Balbi M, Mas MD, Casarin P, Zanette G. Metformin and reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in diabetic patients with chronic liver disease. Liver International. 2010;30:750–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2010.02223.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nkontchou G, Cosson E, Aout M, Mahmoudi A, Bourcier V, Charif I, et al. Impact of metformin on the prognosis of cirrhosis induced by viral hepatitis C in diabetic patients. Journal of clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2011;96:2601–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams LA, Harmsen S, Sauver JL, St, Charatcharoenwitthaya P, Enders FB, Therneau T, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease increases risk of death among patients with diabetes: a community-based cohort study. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;105:1567–73. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kita Y, Takamura T, Misu H, Ota T, Kurita S, Takeshita Y, et al. Metformin prevents and reverses inflammation in a non-diabetic mouse model of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. PloS one. 2012;7:e43056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bugianesi E, Gentilcore E, Manini R, Natale S, Vanni E, Villanova N, et al. A randomized controlled trial of metformin versus vitamin E or prescriptive diet in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2005;100:1082–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garinis GA, Fruci B, Mazza A, De Siena M, Abenavoli S, Gulletta E, et al. Metformin versus dietary treatment in nonalcoholic hepatic steatosis: a randomized study. International journal of obesity. 2010;34:1255–64. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brackett CC. Clarifying metformin's role and risks in liver dysfunction. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. 2010;50:407–10. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2010.08090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown JB, Pedula K, Barzilay J, Herson MK, Latare P. Lactic acidosis rates in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes care. 1998;21:1659–63. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.10.1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2010:CD002967. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002967.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan NN, Brain HP, Feher MD. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: a rare or very rare clinical entity? Diabetic Medicine. 1999;16:273–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.1999.00006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards CM, Barton MA, Snook J, David M, Mak VH, Chowdhury TA. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis in a patient with liver disease. QJM. 2003;96:315–6. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Renda F, Mura P, Finco G, Ferrazin F, Pani L, Landoni G. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis requiring hospitalization. A national 10 year survey and a systematic literature review. European review for medical and pharmacological sciences. 2013;17(Suppl 1):45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misbin RI, Green L, Stadel BV, Gueriguian JL, Gubbi A, Fleming GA. Lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes treated with metformin. New England Journal of Medicine. 1998;338:265–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199801223380415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamber N, Davis WA, Bruce DG, Davis TM. Metformin and lactic acidosis in an Australian community setting: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Medical Journal of Australia. 2008;188:446–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01713.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seidowsky A, Nseir S, Houdret N, Fourrier F. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis: a rognostic and therapeutic study. Critical care medicine. 2009;37:2191–6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181a02490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. The duration of metformin use after the date of cirrhosis diagnosis in the continued metformin group (n=172)

Supplemental Figure 2. Survival of 250 diabetic patients who continued metformin vs. those who discontinued metformin within 1 year after cirrhosis diagnosis

Supplemental Table: Multivariate Cox Proportional Hazards analysis of variables associated with survival of cirrhotic patients with diabetes. This model excluded AFP because 52 patients had missing AFP values