Abstract

Traumatic experiences have been positively associated with both severity of attenuated psychotic symptoms in individuals at high risk (HR) for psychosis and transitions into psychotic disorders. Our aim was to determine what characteristics of the trauma history are more likely to be associated with individuals at HR. The Trauma History Screen (THS) was used to enable emphasis on number and perceived intensity of adverse life events and age at trauma exposure. Sixty help-seeking individuals who met HR criteria were compared to a random sample of 60 healthy volunteers. Both groups were aged 16–35 and resided in the same geographical location. HR participants experienced their first trauma at an earlier age, continued to experience trauma at younger developmental stages, especially during early/mid adolescence and were exposed to a high number of traumas. They were more depressed and anxious, but did not experience more distress in relation to trauma. Both incidences of trauma and age at which trauma occurred were the most likely predictors of becoming HR. This work emphasises the importance of assessing trauma characteristics in HR individuals to enable differentiation between psychotic-like experiences that may reflect dissociative responses to trauma and genuine prodromal psychotic presentations.

Keywords: At-risk-mental-state, High-risk, Psychotic-like, Schizophrenia, Trauma

Highlights

-

•

High risk (HR) individuals experienced more traumas than healthy volunteers (HVs).

-

•

HR individuals did not report more distress associated with trauma than HVs.

-

•

HR individuals suffered first incidents of trauma at earlier ages than HVs.

1. Introduction

Psychosis has been linked with a history of adverse life events (Read et al., 2005, Morgan et al., 2007, Bendall et al., 2008, Bebbington et al., 2011, Fisher et al., 2010, Varese et al., 2012). Traumatic experiences, especially in childhood and early adolescence, appear to be related to psychosis in a dose–response fashion. The number of traumas has been positively associated with severity of attenuated psychotic symptoms in individuals at clinical high risk (HR) for psychosis and, eventually, transitions into frank psychotic disorders (Thompson et al., 2009, Bechdolf et al., 2010)

It is noteworthy that overall transition rates reported in different cohorts of individuals at clinical HR have consistently declined over the last decade (Yung et al., 2007). Subsequently, it has been suggested that HR mental states for psychosis may lack diagnostic specificity and predictive value. Indeed, the presence of psychotic-like symptoms in young people with disorders of anxiety and depression is more prevalent than previously considered (Wigman et al., 2012a, Hui et al., 2013). Furthermore, psychotic-like experiences found in adolescent populations may act not only as markers for psychosis but also for other non-psychotic psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety (Kelleher et al., 2012).

These findings raise the question about whether life stressors should exclusively be investigated as predictors of conversion to psychosis or also as potential contributing factors to HR mental states. In fact, early traumatic life events are common in people at HR (Tikka et al., 2013, Addington et al., 2013) who usually also present with significant morbidity and functional impairment regardless of whether they develop a full-blown psychotic disorder (Zimbron et al., 2012, Hui et al., 2013). Accordingly, addressing trauma in this population might help develop successful therapeutic interventions.

To achieve this ultimate goal it is important to obtain meaningful clinical information that should ideally consider the potential variability in both objective consequences and subjective perceptions after similar traumatic events among different individuals. This element has been neglected in the majority of measures assessing traumatic experiences, which usually survey a broad range of potential stressors and only ask for details of any events endorsed, including those that may not have been significantly distressing (Norris and Hamblen, 2004).

The importance of assessing the degree to which the objective event was subjectively traumatic has been proposed by Spauwen et al. (2006) and Kelleher et al. (2013) with the inference that this may have an impact on risk for psychotic experiences (Kelleher et al., 2013). In concurrence, Wigman et al. (2012b) recommended using social stress as a proxy measure of sensitisation to traumatic experiences to aid understanding of any interactions between trauma and proneness towards psychosis. Furthermore, Addington et al. (2013) emphasised the need to detail both the age at which the trauma occurred and the frequency of trauma over time. Therefore, different combinations of trauma factors, such as perceived severity and frequency of sudden adverse life events, as well as age at trauma exposure, could help better understand different responses among individuals and the likelihood of developing a particular psychiatric manifestation (Carlson et al., 2011).

Another recognised limitation is the absence of matched healthy controls in studies investigating the relationship between trauma and psychotic symptoms (Thompson et al., 2009). This omission may also affect the conclusions to be drawn with regards to trauma prevalence.

By addressing the limitations of previous research, the aim of this study was to determine what characteristics of the trauma history are more likely to be associated with HR mental states in young people referred to mental health services in comparison with a sample of healthy volunteers recruited from the same geographical area. We particularly focused on the number and perceived intensity of adverse life events and age at trauma exposure.

2. Methods

2.1. Setting

CAMEO (http://www.cameo.nhs.uk) is an early intervention in psychosis service which offers management for people aged 14–35 years suffering from first-episode psychosis (FEP) in Cambridgeshire, UK. CAMEO also accepts referrals of people at HR. Referrals are accepted from multiple sources including general practitioners, other mental health services, school and college counsellors, relatives and self-referrals (Cheng et al., 2011).

2.2. Sample

A consecutive cohort of 60 help-seeking individuals, aged 16–35, referred to CAMEO from February 2010 to September 2012 met criteria for HR, according to the Comprehensive Assessment of At Risk Mental States (CAARMS; Yung et al., 2005). Referrals came to our offices via a number of different routes including self-referral, carers and relatives, schools and colleges, but mainly Primary Care. All individuals identified as HR for psychosis living and detected in Cambridgeshire and Peterborough were offered a systematic follow-up in the context of a prospective, naturalistic study called PAATH: Prospective Analysis of At-risk-mental-states and Transitions into PsycHosis. Participants were followed-up for 2 years from the initial referral date. During this period, they were asked to attend subsequent interviews where they completed structured interviews and questionnaires. These questionnaires targeted different domains, such as socio-demographic characteristics, diagnosis, psychiatric morbidity, trauma history, substance use and functioning, among others.

In our sample, all individuals fulfilled criteria for the attenuated psychotic symptoms group. Seven individuals (11.7%) also qualified for the vulnerability traits group (individuals with a family history of psychosis in first degree relative OR schizotypal personality disorder PLUS a 30% drop in GAF score from premorbid level, sustained for a month, occurred within the past 12 months OR GAF score of 50% or less for the past 12 months). Intake exclusion criteria included: i) acute intoxication or withdrawal associated with drug or alcohol abuse or any delirium, ii) confirmed intellectual disability (Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – tested IQ <70), or iii) prior total treatment with antipsychotics for more than 1 week.

During the same period (February 2010–September 2012), a random sample of 60 healthy volunteers (HVs) was recruited by post, using the Postal Address File (PAF®) provided by Royal Mail, UK. To ensure that each HR and HV resided in the same geographical location, 50 corresponding postcodes, matching the first 4/5 characters and digits of each recruited HR participant (e.g. PE13 5; CB5 3), were randomly selected using Microsoft SQL Server, a relational database management system, in conjunction with the PAF database. Each of these 50 addresses was sent a recruitment flyer containing a brief outline of the study, inclusion criteria and contact details. If this failed to generate recruits, a consecutive sample of postcodes would be selected. This process was repeated until a match was recruited. An average of 100 flyers was sent to each postcode to recruit the 60 HV participants. HVs interested in the study could only participate if they were aged 16–35, resided in the same geographical area as HR participants (Cambridgeshire), and did not have previous contact with mental health services.

2.3. Ethical approval

Ethical approval was granted by the Cambridgeshire East Research Ethics Committee.

2.4. Measures

All participants were assessed with sociodemographic (age, gender, ethnicity and occupational status), trauma and clinical measures at the time of their referral to CAMEO. The assessments were carried out by senior research clinicians trained in each of the measurement tools.

HR participants were interviewed by senior trained psychiatrists working in CAMEO, using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI), Version 6.0.0 (Sheehan et al., 1998), a brief structured diagnostic interview for DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1987) for psychotic symptoms was also employed to capture the severity of positive symptoms (seven items), negative symptoms (seven items) and general psychopathology (16 items) in a 7-point scale, with higher scores indicating greater severity of illness.

To address the limitations of previous trauma measurement tools, the Trauma History Screen (THS; Carlson et al., 2011) was selected for this study. The THS was developed as a brief, easy to complete self-report measure of exposure to both high magnitude stressor events that could be traumatic (HMS) and events associated with significant and persisting posttraumatic distress (PPD). It assesses exposure to severe stressors which the authors define as sudden events that have been found to cause extreme distress in most of those exposed (HMS) and events associated with significant subjective distress that lasts more than a month (PPD) events. The authors propose that the theoretical rational for including the specific stressor categories was that suddenness, lack of controllability, and a strong negative valence are all necessary, although not sufficient, characteristics for an event to cause traumatic stress (Carlson and Dalenberg, 2000).

The THS was developed to provide information about exposure to stressor events and about the severity and duration of emotional responses to stressful events. The reliability and validity of the THS have been demonstrated in clinical and non-clinical samples of homeless veterans, hospital trauma patients and their families, university students and adults and young adults from a community sample (Carlson et al., 2011). The reliability in these samples was good to excellent with median kappa coefficients of agreement for items ranging from 0.61 to 0.77. Construct validity was also supported by findings of strong convergent validity with a longer measure of trauma exposure and by correlations of THS scores between r=0.73 and 0.77 with PTSD symptoms.

This brief measure with a simple format and an easy reading level includes a gate question after the initial trauma checklist which is designed to only record details concerning events that were significantly distressing. The THS assesses trauma load, frequency and the distress caused by the traumatic events. It is a 13-item self-report measure that examines 11 events and one general event, including military trauma, sexual assault and natural disasters. For each event, respondents are asked to indicate whether the event occurred (‘yes’ or ‘no’) and the number of times something like this happened. For each event endorsed as emotionally troubling additional dimensions are assessed, including age when it happened, a description of what happened, whether there was actual or a threat of death or injury, feelings of helplessness and feelings of dissociation, a 4-point scale for duration of distress (‘not at all’ to ‘a month or more’) and a 5-point scale for distress level (‘not at all’ to ‘very much’).

The Beck Depression Inventory, Version II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; Beck and Steer, 1993) were used to assess depressive and anxiety symptoms respectively. BDI-II and BAI are widely used self-report instruments to assess depressive and anxiety symptom severity in the past 2 weeks. Each of them consists of 21 items rated on a 4-point scale from absent (0), mild (1), moderate (2) to severe (3). Composite scores (range 0–63 points) were generated by summing up individual items. Scores obtained from both measures were then used to analyse possible correlations with age at trauma exposure, number and intensity of traumatic events and associated distress.

2.5. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software (R Core Team, 2013). For demographic comparisons between HR individuals and healthy volunteers Fisher׳s exact test was used. Overall number of traumas and age trauma occurred were compared using negative binomial regression. Poisson regression was used to compare individual traumas in both groups. t-Test was used for intensity of trauma comparisons. We calculated Pearson correlations to evaluate possible associations between age at which trauma occurred, number and intensity of traumas, BDI-II and BAI. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the importance of age at trauma exposure, intensity and number of traumas with regards to the presence of HR mental states. We also presented graphical comparisons of both groups using box plots.

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic profile

Sociodemographic information was collected, comprising age, gender, ethnicity and occupational status. Table 1 shows a comparison between HR and HV individuals. There was a difference in age between the two groups; HVs were significantly older than the HR participants (t=−3.97, d.f.=86, p≤0.001). The HR group had a slightly higher proportion of males and the HV group had a slightly higher proportion of females. Both groups were predominantly white with a similar proportion of Mixed, Asian and Black participants. Both groups contained the same number of students (41.7%), but significantly more HV participants were employed (p=0.001).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic comparison between HR and HV participants.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | HR (n=60) | HV (n=60) | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at study entry, years (median, min, max, S.D.) | 19.89 (16.41, 30.21, 2.38) | 22.60 (16.18, 35.57, 5.68) | <0.001⁎ |

| Gender (n, %) | |||

| Male | 31 (51.7%) | 26 (43.3%) | 0.465~ |

| Female | 29 (48.3%) | 34 (56.7%) | 0.465~ |

| Ethnicity (n, %)† | |||

| White | 56 (93.3%) | 55 (91.7%) | 1.000~ |

| Mixed | 2 (3.3%) | 2 (3.3%) | 1.000~ |

| Asian | 1 (1.7%) | 2 (3.3%) | 1.000~ |

| Black | 1(1.7%) | 1(1.7%) | 1.000~ |

| Occupational status (n, %) (7)‡ | |||

| Unemployed | 20 (33.3%) | 8 (13.3%) | 0.004~ |

| Employed | 8 (13.3%) | 27 (45.0%) | 0.001~ |

| Students | 25 (41.7) | 25 (41.7) | 0.575~ |

‘P-values’ ⁎=t-test ~=Fisher׳s exact.

† ‘White ethnicity’ refers to subjects who are White British, White Irish, or other White backgrounds.

‘Mixed ethnicity’ refers to those who are White and Black Caribbean, mixed White and Black African, mixed White and Asian, or any other mixed backgrounds.

‘Asian ethnicity’refers to those who are Indian or Chinese.

‘Black ethnicity’ refers to subject from any Black backgrounds.

‡ Occupational status is broadly categorised into three groups.

‘Unemployed’ includes subjects who do not have a job, either they are looking for work, not looking for work (e.g., housewife), or not being able to work due to medical reasons.

‘Employed’refers to people who have full/part-time employment, or employed but currently unable to work.

‘Students’ refers to full/part-time students, including those who are also working some hours.

3.2. Psychiatric diagnoses and PANSS scores

We obtained MINI DSM-IV diagnoses for 55 of the 60 HR individuals. Thirty eight (69.1%) had more than one DSM-IV psychiatric diagnosis, mainly within the affective and anxiety diagnostic spectra. Primary diagnoses for this group were ranked as follows: major depressive episode, current or recurrent (n=26; 47.3%)>social phobia (n=7; 12.7%)=generalised anxiety disorder (n=7; 12.7%)>obsessive compulsive disorder (n=5; 9.1%)>bipolar disorder, type II (n=2; 3.6%)>panic disorder (n=1; 1.8%)=posttraumatic stress disorder (n=1; 1.8%). Six HR individuals (10.9%) did not fulfill sufficient criteria for a DSM-IV Axis I diagnosis.

The mean PANSS scores for the HR group comprised positive symptoms (13.1, S.D.=3.2), negative symptoms (12.4, S.D.=5.0) and general psychopathology (32.7, S.D.=7.0). These scores indicated a ‘mildly ill’ group with regards to psychotic symptoms (Leucht et al., 2005). Psychotic symptoms for the HV group were subclinical. The study protocol did not routinely administer a MINI for HV. However, if information elicited with the battery of questionnaires indicated any concerns about mental state, the protocol was to administer a MINI for verification. This was not the case for any of the HV.

3.3. Trauma history

3.3.1. Number of traumatic events

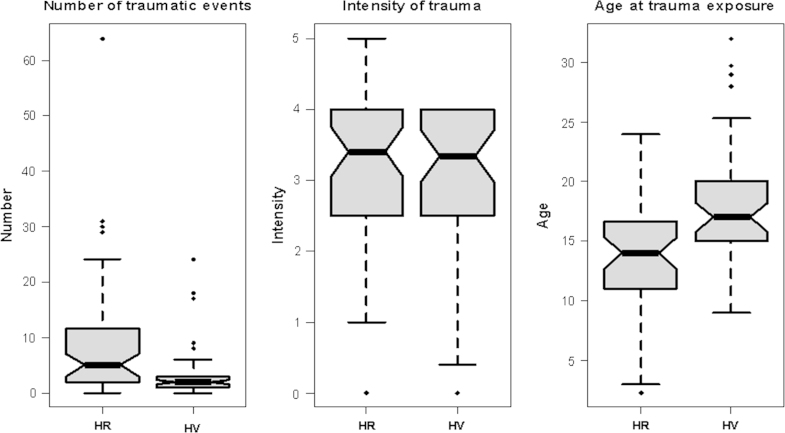

The THS assesses lifetime exposure to 14 potentially traumatic events. Table 2 shows how many HR and HV participants had experienced an event described on the screen and compares the total number of times each trauma occurred for HR and HV participants. Seventy-five per cent of HR participants reported experiencing at least one trauma in their lifetime, compared to 68% of the HV group. Neither group had experienced a traumatic event during military service. With the exception of a disaster (hurricane, flood, earthquake, tornado, fire) and sudden death of close family or friend, more HR participants had experienced the different types of trauma than HV participants. This finding was replicated in the total number of times each trauma occurred. The mean number of all traumatic events was calculated for HR (8.6, S.D.=11.4) and HV (3.2, S.D.=4.8) participants (see Fig. 1). Based on a negative binomial model, this difference was statistically significant (p≤0.001). There was one outlier scoring 69 traumatic events. However, analysis omitting this value revealed no significant differences in the results.

Table 2.

Endorsement rates for each traumatic event and total number of times each trauma occurred for HR and HV participants.

| Event | Endorsement rates for each traumatic event |

Total N of times each trauma occurred |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (%) | HV (%) | HR | HV | p-Value~ | |

| A really bad car, boat, train, or airplane accident | 5 (8.3%) | 6 (10.0%) | 14 | 6 | 0.039 |

| A really bad accident at work or home | 10 (16.7%) | 5 (8.3%) | 21 | 8 | 0.007 |

| A hurricane, flood, earthquake, tornado, or fire | 2 (3.3%) | 7 (11.7%) | 2 | 14 | 0.018 |

| Hit or kicked hard enough to injure – as a child | 17 (28.3%) | 7 (11.7%) | 95 | 47 | <0.001 |

| Hit or kicked hard enough to injure – as an adult | 14 (23.3%) | 8 (13.3%) | 83 | 18 | <0.001 |

| Forced or made to have sexual contact – as a child | 5 (8.3%) | 3 (5.0%) | 14 | 4 | 0.013 |

| Forced or made to have sexual contact – as an adult | 5 (8.3%) | 1 (1.7%) | 11 | 2 | 0.015 |

| Attack with a gun, knife, or weapon | 14 (23.3%) | 6 (10.0%) | 24 | 7 | 0.001 |

| During military service – seeing something horrible or being badly scared | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sudden death of close family or friend | 23 (38.3%) | 31 (51.7%) | 47 | 53 | 0.833 |

| Seeing someone die suddenly or get badly hurt or killed | 17 (28.3%) | 10 (16.7%) | 32 | 10 | <0.001 |

| Some other sudden event that made you feel very scared, helpless, or horrified | 23 (38.3%) | 12 (20.0%) | 58 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Sudden move or loss of home and possessions | 7 (11.7%) | 3 (5.0%) | 13 | 3 | 0.011 |

| Suddenly abandoned by spouse, partner, parent, or family | 16 (26.7%) | 5 (8.3%) | 24 | 6 | <0.001 |

=Fisher׳s exact.

Fig. 1.

Box plots to show the distribution of traumatic events, intensity of trauma and age at trauma exposure for HR and HV participants.

When each type of traumatic event was considered separately, being hit or kicked hard enough to injure, both as a child and an adult, showed the largest differences between HR and HV participants. Further analysis using Poisson regression revealed that physical abuse both as a child (p≤0.001) and an adult (p≤0.001), witnessing death or injury (p≤0.001), events that induced feelings of fear, helplessness or horror (p≤0.001) and abandonment (p≤0.001) where significantly more frequent for HR participants than HV participants (see Table 2).

The THS (Carlson et al., 2011) then asks ‘Did any of these things really bother you emotionally? NO YES’. The subsequent analyses were conducted only on those events acknowledged as YES. For HR participants, this was 39% of the total number of all traumatic events reported and for HV participants, it was 32.2%.

3.3.2. Intensity of traumatic events

Up to 70% of traumatic events were reported as distressing. To assess the intensity of traumatic events, the mean perceived level of distress for each emotionally troubling event was calculated (How much did it bother you emotionally? not at all/a little/somewhat/much/very much). Fig. 1 shows that experiences of distress were very similar between the groups (HR=3.1, S.D.=1.14; HV=3.0, S.D.=1.3). Results of a two sample t-test revealed that there was no significant difference between groups in terms of trauma intensity (t=0.4175, d.f.=84, p=0.6774).

3.3.3. Age traumatic events occurred

Fig. 1 shows that the mean age of exposure to all traumas for HR participants was 13.6 (S.D.=4.3, median=14) and 17.8 (S.D.=5.1, median=17) for HV participants. In instances where individuals had more than one exposure to trauma, the mean age was calculated initially. Results of a two sample t-test revealed that HR participants were exposed to trauma at a significantly younger age than HV participants (t=−3.974, d.f.=84, p-value<0.001). Further analyses confirmed that the mean age HR participants experienced their first trauma was 9.8 (S.D.=5.5, median=9), while for HV participants it was 16.5 (S.D.=6.0, median=16). To determine any prevalent developmental stage that trauma occurred, the number of traumatic events was stratified by age and group. Analyses revealed that, for both groups, the most traumas occurred between the ages of 9–16 and 17–24, with HR volunteers experiencing more trauma than HV participants during both these stages. HR participants experienced significantly more traumas between the ages of 0 and 8 (p≤0.001). Conversely, HV participants experienced more traumas between the ages of 25 and 35. However, due to the lack of variance within the HR group, significance could not be tested.

3.3.4. Relationship between number of traumas, trauma intensity, age at trauma exposure, depression and anxiety

Cronbach׳s alphas for the 21 BDI and 21 BAI items were 0.96 and 0.95 respectively, indicating high reliability for both measures.

HR participants had a higher total BDI-II score (i.e., more depressed) than HVs (29.9, S.D.=12.8 vs. 6.7, S.D.=6.5, p≤0.001). Similarly, total BAI scores revealed that HR individuals had more anxiety symptoms (28.9, S.D.=11.9 vs. 8.5 S.D.=8.0, p≤0.001). Furthermore, 61.7% of HR participants suffered moderate or severe depression and 85.4% suffered moderate or severe anxiety.

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for the relationships between among trauma incidence, trauma intensity, depression, anxiety and age (Table 3). Results showed that both BDI and BAI sum scores were significantly correlated with the number of traumatic events and age of trauma. The higher the number of traumatic events, the higher the BDI and BAI scores. Conversely, the lower the age that traumatic events occurred, the higher the BDI and BAI scores. Trauma intensity was not correlated with BDI or BAI scores.

Table 3.

Pearson correlation coefficients for the relationships between number of traumas, trauma intensity, age at trauma exposure, depression and anxiety for the whole sample.

| BAI | BDI | Number of traumas | Age at trauma exposure | Trauma intensity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAI | 1 | ||||

| BDI | 0.700⁎⁎ | 1 | |||

| Number of traumas | 0.470⁎⁎ | 0.230⁎ | 1 | ||

| Age at trauma exposure | −0.380⁎⁎ | −0.350⁎⁎ | −0.170 | 1 | |

| Trauma intensity | 0.200 | 0.160 | 0.160 | 0.050 | 1 |

BDI-II=Beck Depression Inventory, Version II, BAI=Beck Anxiety Inventory.

p≤0.05.

p≤0.001.

3.3.5. Number of traumas, trauma intensity and age at trauma exposure as predictors of HR

A logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine the impact of traumatic events, age at traumatic event or event intensity on the likelihood of being HR. In light of the significant differences between the groups in age at study entry, and because age might be related to number of events or age of trauma, age at study entry was entered as a covariate in the model. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Summary of logistic regression analysis for variables predicting HR.

| Parameter | Regression coefficient | Standard error | Wald p-value | Odds ratio | 95% CI of odds ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.147 | 0.063 | 0.019 | 0.863 | (0.764, 0.976) |

| Number of traumas | 0.104 | 0.045 | 0.019 | 1.11 | (1.017, 1.211) |

| Age at trauma exposure | −0.135 | 0.067 | 0.042 | 0.873 | (0.766, 0.995) |

| Trauma intensity | −0.04 | 0.206 | 0.848 | 0.961 | (0.643, 1.438) |

In support of our previous findings, intensity was not a statistically significant predictor of being HR. However, both age at traumatic event and number of traumatic events were statistically significant predictors. Every traumatic event (while all other variables in the model were held constant) represented an odds ratio of 1.11. Each year (while other variables in the model were held constant) represented a reduced likelihood that a participant will be HR by 0.873.

3.3.6. Transitions from high risk (HR) to first episode psychosis (FEP)

After more than 1 year of follow-up for each individual at HR in our sample, only six (10%) made a transition into FEP. None of the HR individuals from this cohort received antipsychotics during the follow-up period.

4. Discussion

The aim of this study was to determine whether number of traumatic events, perceived intensity of traumatic events or age at trauma exposure is more likely to be associated with HR mental states. To achieve this, the prevalence of past traumatic experiences and the constituent characteristics of those experiences were compared between samples of individuals at HR of developing psychosis and HVs.

The finding that HR participants had both a higher incidence of trauma and reported repeated exposure to trauma than HVs supports the possibility of an association between trauma and psychotic-like symptoms. Several studies have reported that repeated exposure/increasing frequency is linked to stronger associations with sub-clinical psychotic symptoms (de Loore et al., 2007, Arseneault et al., 2011) and transitions to psychosis (Read et al., 2005, Thompson et al., 2009, Bechdolf et al., 2010). Another alternative explanation for these findings could be the role of the HR׳s individual behaviour in the occurrence of traumatic events. Kendler et al. (1999) reported the association between stressful life events and onset of depression can be explained by individuals selecting themselves into high risk situations. In concurrence, Stein et al. (2002) proposed that individual differences in personality influence environmental choices. These genetic factors can increase an individual׳s risk of exposure to some forms of trauma. Therefore, it is possible that the HR individuals in this study were more likely to self-select a high risk environment.

Traumatic events involving physical abuse with intention to harm accounted for the largest proportion of reported trauma for both groups and showed the largest differences between HV and HR participants. This supports previous conjecture that an element of threat, or a perception of threat, rather than the nature of the trauma (e.g., physical, sexual or emotional) could be more important in understanding any links between psychotic symptoms and trauma (Arseneault et al., 2011).

It is possible that this large difference can be explained by the conjecture that HR individuals are prone to paranoid thinking. Conversely, it has been suggested that beliefs about threat to the self can emerge as a response to interpersonal stress and trauma. Pre-existing negative beliefs about the self can combine with threatening appraisals of others resulting in anxiety. Feelings of threat and paranoia ensue leading to an increased likelihood of persecutory delusions (Freeman et al., 2002). Furthermore, anxiety has been shown to be predictive of the occurrence of paranoid thoughts (Freeman et al., 2008) and of the persistence of persecutory delusions (Startup et al., 2007). Indeed, Freeman and Fowler (2009) proposed that trauma influences persecutory thinking non-specifically via the creation of anxiety. This association between negative beliefs about self and others, anxiety and paranoia is supported by the high levels of anxiety in this study׳s HR group.

Associations between trauma and psychotic symptoms have also been found for emotional and physical trauma (Read et al., 2005), with more severe trauma (e.g. sexual) displaying the strongest associations (Read et al., 2005, Bechdolf et al., 2010, Thompson et al., 2014).

Conversely, in the present study, events involving sexual abuse were comparatively low for both groups: 16.6% in HR and 6.6% in HV. Two recent studies reported much higher rates of 27% and 28% in samples at clinical high risk for psychosis (Thompson et al., 2009, Bechdolf et al., 2010). This was particularly notable considering the age range of the participants in the present study was 10 years greater than these two studies. Indeed, Bechdolf et al. (2010) found that history of sexual trauma predicted conversion to psychotic disorder. Even longitudinal data from individuals at HR suggested a relationship between experience of sexual abuse and the medium-to-long term development of a psychotic disorder (Thompson et al., 2014). It could be argued that lack of sexual abuse in the present study may be an ameliorating factor against transition.

Results showed that although HR participants experienced significantly more traumatic events than HVs, they did not report any more distress in relation to these events. Despite 60–70% of all individuals reporting distress in response to traumatic events, it is of note that, for both groups, 30–40% of traumatic experiences were not judged to be emotionally distressing. This was corroborated by the presence of only a single case of PTSD in the whole sample. An explanation of this finding is that because HR individuals are exposed to more recurrent traumatic events, they have become more desensitised to the impact and therefore, the threshold for distress associated with the events is reduced. This may go some way to explaining their greater risk of exposure. Another consideration is the possibility that the perceived intensity of trauma is a future predictor of psychopathology other than psychosis. This highlights the relevance of understanding the emotional impact of trauma on the subjective perceptions of the individual which can extend our understanding of why particular events cause traumatic stress in particular individuals.

First incidents of trauma and total number of traumas occurred at earlier ages for HR participants and HR participants experienced significantly more traumas during the developmental period between the ages 0 and 8 years. To date, there has been no conclusive research identifying the most vulnerable developmental period for the risk-increasing effects of trauma (Wigman et al., 2012b) and previous studies have found that the cumulative effect of trauma during early to late childhood, rather than the timing, confers the highest risk for developing psychotic symptoms (Arseneault et al., 2011).

A key finding of the current study was that both incidences of trauma and age at which trauma occurred were the most likely predictors of becoming HR, not the degree of distress reported as result of the trauma. Certainly, previous studies have consistently found strong associations with early childhood trauma and psychotic symptoms (Freeman and Fowler, 2009, Arseneault et al., 2011) and it has been suggested that this is because young children may lack the coping strategies needed to deal with the consequences of experiencing trauma (Arseneault et al., 2011). In this study the higher instances of trauma occurred between 9 and 24 years rather than 0 and 8 years. Also, the median age for first trauma was 9 and for all traumas 14. In light of previous findings, it is possible to interpret this lack of earlier trauma as another ameliorating factor against transition to full psychosis, although a longitudinal design would be necessary to substantiate this. Similarly, previous research revealed a high prevalence of trauma in patient cohorts with established psychotic disorder (Read et al., 2005) and in those at risk of developing psychosis (Thompson et al., 2014). Also, associations have been reported between numbers of traumatic events and clinically high risk samples in recent studies, reporting a 97% and 69.6% prevalence rate of at least one trauma (Thompson et al., 2009, Bechdolf et al., 2010), although incidence of successive trauma was not delineated in either of these studies. Nevertheless, it has been shown that the accumulation of trauma increases the risk to develop subclinical psychotic experiences in a dose–response fashion (de Loore et al., 2007). This seems to suggest that, in this study, regardless of the subjectively perceived distress as result of the trauma, both higher incidents of trauma and younger ages at trauma exposure increased the likelihood of being at HR. Higher ages for trauma exposure and lack of sexual abuse could be ameliorating factors for the HR individuals in this study.

Previous research has found the majority of help-seeking individuals at HR initially present with anxiety disorder or major depression (Velthorst et al., 2009, Addington et al., 2011, Wigman et al., 2012a, Hui et al., 2013) and the association of trauma and paranoia can be explained by levels of anxiety (Freeman and Fowler, 2009). The high levels of anxiety and depression found in our HR group replicate these findings. Combined with the very low transition rates to date, our low initial conversion rate adds credence to the argument that there is a lack of diagnostic specificity and predictive value in the HR model. Therefore, it is possible to speculate that a HR mental state is not a specific marker for psychosis. Supplement this with the prevalent co-presence of anxiety and depression in this group, it is feasible to consider that trauma may play a role in this manifestation of symptoms. Indeed, other authors (Spauwen et al., 2006) have also speculated that exposure to trauma may be a hidden factor explaining a substantial part of the morbidity associated with sub-clinical psychosis. This is especially pertinent in light of recent research that suggests the incidence of psychotic experiences decreases significantly when exposure to trauma ceases (Kelleher et al., 2013).

The low transition rates could be explained by the short follow up in this study. The risk for transition is highest in the first 2 years, but transitions can occur up to at least 10 years after presentation (Nelson et al., 2013). Alternatively, it is possible to consider the lack of transitions as an indicator that trauma is not a predictor of psychosis. Therefore, if traumatic experiences are considered as a non-specific marker of psychopathology, their consideration and assessment become paramount. As Carlson et al. (2013) emphasised, traumatic events may not directly cause symptoms, but may precipitate mental disorder in individuals who are vulnerable because of previous, existing or later biological, psychological or social factors. Conversely, a recent study looking at childhood adversity, including diverse events such as separation and abuse, concluded that the combination of childhood abuse and exposure to further stressors establishes an enduring susceptibility to psychosis (Morgan et al., 2014). This accentuates the importance of a detailed consideration of potentially traumatic life events during clinical assessment. The presence of these events combined with the subjective interpretation could be related to the experience of psychotic or psychotic-like phenomena.

There is debate around the events that are included in the measurement of trauma. McNally (2009) has expressed concern that including non-catastrophic events in trauma scales creates an excessively broad definition of a traumatic event, resulting in increased numbers of PTSD diagnoses based on exposure to relatively minor stressors. Shalev and Ursano (2003) contended that if traumatic stressors are only distinguished by perceived threat of injury or death, the essential nature of human traumatisation is lost. They argued that treat is not a necessary condition for being traumatised and elements such as separation, relocation, loss, isolation and uncertainty can be traumatising. Other authors agree, positing that the defining features of traumatic events are negative valence, lack of controllability and suddenness (Carlson and Dalenberg, 2000). Therefore, the authors of the THS maintain that also assessing events involving severe emotional loss or pain such as ‘sudden move or loss of home’ and ‘possessions and sudden abandonment by family or loved ones’ is valid. These events have been associated with posttraumatic symptoms as strongly as Criterion A stressors (Carlson et al., 2013, Van Hooff et al., 2009). Such experiences are common for refugees, survivors of natural disasters and war, and for children in low socioeconomic status families (Carlson et al., 2011). We felt that inclusion of these items in the present study was justified as HR cohorts can have comparable experiences.

Notwithstanding the strengths of this study, the results must be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, the healthy volunteers were statistically significantly older than the high risk participants and this might be interrelated with number of events or age of trauma. However, HR participants still had higher amounts of trauma at younger ages. It is possible that were the groups of a similar age, the differences would only have been greater between the two groups. To adjust for this, age at study entry was entered as a covariate in the logistic regression model. Second, our findings are based on self-report. It is possible that the HR mental state may lead to inaccuracy in the recall and reporting of traumatic experiences. Trauma was measured by the respondent׳s subjective information and not corroborated by independent information; therefore it was not possible to ascertain if trauma was under or overestimated. However, research has shown that even individuals with psychotic disorders can be as accurate in recalling traumatic experiences as a population sample (Kelleher et al., 2013). Conversely, confidential self-report produces twice the number of childhood traumas reported compared with a psychiatric interview (Dill et al., 1991). This indicates that including a combination of methods would yield the most accurate record of trauma. Third, only a crude, one-item measure of distress was used in this study. Future research should include a valid measure to elucidate any relationships between distress, trauma, anxiety and psychotic experiences/symptoms. Fourth, although the THS (Carlson et al., 2011) does examine trauma involving physical abuse as a child and events that induce feelings of fear, helplessness and horror there is no specific question concerning bullying. It is possible that a large proportion of traumatic experiences were missed due to this omission; particularly as research has found an elevated risk for psychosis among bullied children (Arseneault et al., 2011, Addington et al., 2013). Fifth, the study is cross-sectional; without further longitudinal data it is not possible to fully ascertain particular trauma characteristics as predictors of conversion to psychosis or as a contributing factor to HR mental states. Finally, there was no clear definition between the measurement of actual trauma and stressful life events. This may account for the high prevalence of reported trauma in our sample. However, an objective of the THS is to provide substantial information about exposure to potentially traumatic stressors and responses to stressors. Furthermore, we considered it important to include all events that individuals identified as traumatic, as the accumulation of these events may have an impact on the development of psychotic-like experiences as proposed by Morgan et al. (2014). Life stressors as well as true trauma are important considerations in developing psychopathology, irrespective of the character of the psychotic phenomenon.

Our work adds to the literature concerning the understanding of trauma in HR mental states. It emphasises the clinical importance of thoroughly assessing trauma characteristics in individuals at clinical HR in order to enable differentiation between psychotic-like experiences that may reflect dissociative responses to trauma and genuine prodromal psychotic presentations. Subsequently, this will help understand the links between traumatic events, psychotic-like symptoms and other non-psychotic psychiatric disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR; programme grant RP-PG-0606-1335 ‘Understanding Causes and Developing Effective Interventions for Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses’ awarded to P.B.J.). The work forms part of the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research & Care for Cambridgeshire & Peterborough (CLAHRC-CP). The NIHR had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors have not transmitted any conflicts of interest based on business relationships of their own or of immediate family members.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the PAATh Study team (Gillian Shelley, Chris McAlinden, Carolyn Crane and Gerhard Smith) and all members of CAMEO services for their help and support with this study.

References

- Addington J., Stowkowy J., Cadenhead K.S., Cornblatt B.A., McGlashan T.H., Perkins D.O., Seidman L.J., Tsuang M.T., Walker E.F., Woods S.W., Cannon T.D. Early traumatic experiences in those at clinical high risk for psychosis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2013;7(3):300–305. doi: 10.1111/eip.12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addington J., Cornblatt B.A., Candenhead K.S., Cannon T.D., McGlashan T., Perkins D.O., Seidman L., Tsuang M.T., Walker E.F., Woods S., Heinssen R. At clinical high risk for psychosis: outcome for nonconverters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:800–805. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneault L., Cannon M., Fisher H.L., Polanczyk G., Moffitt T.E., Caspi A. Childhood trauma and children׳s emerging psychotic symptoms: a genetically sensitive longitudinal cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:65–72. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebbington P., Jonas S., Kuipers E., King M., Cooper C., Brugha T., Meltzer H., McManus S., Jenkins R. Childhood sexual abuse and psychosis: data from a cross-sectional national psychiatric survey in England. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;199:29–37. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechdolf A., Stompson A., Nelson B., Cotton S., Simmons M.B., Amminger G.P., Leicester S., Francey S.M., McNab C., Krstev H., Sidis A., McGorry P.D., Yung A.R. Experience of trauma and conversion to psychosis in an ultra-high-risk (prodromal) group. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2010;121:377–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2010.01542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A., Ball R., Ranieri W. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and -II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67(3):588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A.T., Steer R.A. Harcourt Brace and Company; San Antonio: 1993. Beck Anxiety Inventory Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Bendall S., Jackson H.J., Hulbert C.A., McGorry P.D. Childhood trauma and psychotic disorders: a systematic, critical review of the evidence. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008;34:568–579. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.B., Smith S.R., Palmieri P.A., Dalenberg C., Ruzek J.I., Kimerling R., Burling T.A., Spain D.A. Development and validation of a brief self-report measure of trauma exposure: the Trauma History Screen. Psychological Assessment. 2011;23(2):463–477. doi: 10.1037/a0022294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.B., Dalenberg C. A conceptual framework for the impact of traumatic experiences. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. 2000;1:4–28. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson E.B., Smith S.R., Dalenberg C.J. Can sudden, severe emotional loss be a traumatic stressor? Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2013;14(5):519–528. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2013.773475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F., Kirkbride J.B., Lennox B.R., Perez J., Masson K., Lawrence K., Hill K., Feeley L., Painter M., Murray G.K., Gallagher O., Bullmore E.T., Jones P.B. Administrative incidence of psychosis assessed in an early intervention service in England: first epidemiological evidence from a diverse, rural and urban setting. Psychological Medicine. 2011;41(5):949–958. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Loore E., Drukker M., Gunther N., Feron F., Deboutte D., Sabbe B., Mengelers R., van Os J., Myin-Germey I. Childhood negative experiences and subclinical psychosis in adolescents: a longitudinal general population study. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2007;1:201–207. [Google Scholar]

- Dill D.L., Chu J.A., Grob M.C., Eisen S.V. The reliability of abuse history reports: a comparison of two inquiry formats. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1991;32:166–169. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(91)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher H.L., Jones P.B., Fearon P., Craig T.K., Dazzan P., Morgan K., Hutchinson G., Doody G.A., McGuffin P., Leff J., Murray R.M., Morgan C. The varying impact of type, timing and frequency of exposure to childhood adversity on its association with adult psychotic disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2010;40:1967–1978. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Fowler D. Routes to psychotic symptoms: trauma, anxiety and psychosis like experiences. Psychiatry Research. 2009;169(2):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Pugh K., Antley A., Slater M., Bebbington P., Gittins M., Dunn G., Kuipers E., Fowler D., Garety P. A virtual reality study of paranoid thinking in the general population. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;192:258–263. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.044677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman D., Garety P., Kuipers E., Fowler D., Bebbington P. A cognitive model of persecutory delusions. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2002;41:331–347. doi: 10.1348/014466502760387461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui C., Morcillo C., Russo D.A., Stochl J., Shelley G.F., Painter M., Jones P.B., Perez J. Psychiatric morbidity and disability in young people at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2013;48(1–3):175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kay S.R., Fiszbein A., Opler L.A. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I., Keeley H., Corcoran P., Ramsay H., Wasserman C., Carli V., Sarchiapone M., Hoven C., Wasserman D., Cannon M. Childhood trauma and psychosis in a prospective cohort study: cause, effect, and directionality. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170:734–741. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12091169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelleher I., Keeley H., Corcoran P., Lynch F., Fitzpatrick C., Devlin N., Molloy C., Roddy S., Clarke M.C., Harley M., Arseneault L., Wasserman C., Carli V., Sarchiapone M., Hoven C., Wasserman D., Cannon M. Clinicopathological significance of psychotic experiences in non-psychotic young people: evidence from four population-based studies. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;1:26–32. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.101543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler K.S., Karkowski L.M., Prescott C.A. Causal relationship between stressful life events and the onset of major depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:837–841. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leucht S., Kane J.M., Kissling W., Hamann J., Etschel E., Engel R.R. What does the PANSS mean? Schizophrenia Research. 2005;79(2–3):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally R.J. Can we fix PTSD in DSM-V? Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:597–600. doi: 10.1002/da.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C., Kirkbride J., Leff J., Craig T., Hutchinson G., McKenzie K., Morgan K., Dazzan P., Doody G.A., Jones P., Murray R., Fearon P. Parental separation, loss and psychosis in different ethnic groups: a case-control study. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:495–503. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan C., Reininghaus U., Reichenberg A., Frissa S., SELCoH study team. Hotopf M., Hatch S.L. Adversity, cannabis use and psychotic experiences: evidence of cumulative and synergistic effects. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;204:346–353. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson B., Yuen H., Wood S.J., Lin A., Spiliotacopoulos D., Bruxner A., Broussard C., Simmons M., Foley D.L., Brewerm W.J., Francey S.M., Amminger G.P., Thompson A., McGorry P.D., Yung A.R. Long-term follow-up of a group at ultra high risk (“prodromal”) for psychosis: the PACE 400 study. Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry. 2013;70(8):793–802. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris F.H., Hamblen J.L. In: Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD. Wilson J., Keane T.M., editors. The Guilford Press; New York: 2004. Standardized self-report measures of civilian trauma and PTSD; pp. 63–102. [Google Scholar]

- Read J., van Os J., Morrison A.P., Ross C.A. Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2005;112:330–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. (URL) [Google Scholar]

- Shalev A.Y., Ursano R.J. In: Reconstructing Early Intervention After Trauma. Orner R., Schnyder U., editors. Oxford University Press; Oxford, England: 2003. Mapping the multidimensional picture of acute responses to traumatic stress; pp. 228–235. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan D.V., Lecrubier Y., Sheehan K.H., Amorim P., Janavs J., Weiler E., Hergueta T., Baker R., Dunbar G.C. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1998;59(20):22–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spauwen J., Krabbendam L., Lieb R., Wittchen H.U., van Os J. Impact of psychological trauma on the development of psychotic symptoms: relationship with psychosis proneness. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;188:527–533. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.011346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Startup H., Freeman D., Garety P.A. Persecutory delusions and catastrophic worry in psychosis: developing the understanding of delusion distress and persistence. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007;45:523–537. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein M.B., Lang K.L., Taylor S., Vernon P.A., Livesley W.J. Genetic and environmental influences on trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a twin study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1675–1681. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson A.D., Nelson B., Yuen H.P., Lin A., Amminger G.P., McGorry P.D., Wood S.J., Yung A.R. Sexual trauma increases the risk of developing psychosis in an ultra high-risk “prodromal” population. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2014;40(3):697–706. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbt032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.L., Kelly M., Kimhy D., Harkavy-Friedman J.M., Khan S., Messinger J.W., Schobel S., Goetz R., Malaspina D., Corcoran C. Childhood trauma and prodromal symptoms among individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;108:176–181. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikka M., Luutonen S., Ilonen T., Tuominen L., Kotimäki M., Hankala J., Salokangas R.K.R. Childhood trauma and premorbid adjustment among individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis and normal contral subjects. Early Intervention in Psychiatry. 2013;7:51–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7893.2012.00391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Hooff M., McFarlane A.C., Baur J., Abraham M., Barnes D.J. The stressor Criterion-A1 and PTSD: a matter of opinion? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:77–86. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varese F., Smeets F., Drukker M., Lieverse R., Lataster T., Viechtbauer W., Read J., van Os J., Bentall R.P. Childhood adversities increase the risk of psychosis: a meta-analysis of patient-control, prospective- and cross-sectional cohort studies. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38:661–671. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velthorst E., Nieman D.H., Becker H.E., van de Fliert R., Dingemans P.M., Klaassen R., de Haan L., van Amelsvoort T., Linszen D.H. Baseline differences in clinical symptomatology between ultra high risk subjects with and without a transition to psychosis. Schizophrenia Research. 2009;109:60–65. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigman J.T.W., van Nierop M., Vollebergh W.A., Lieb R., Beesdo-Baum K., Wittchen H.U., van Os J. Evidence that psychotic symptoms are prevalent in disorders of anxiety and depression, impacting on illness onset, risk, and severity—implications for diagnosis and ultra-high risk research. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2012;38(2):247–257. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigman J.T.W., van Winkel R., Ormel J., Verhulst F.C., van Os J., Vollebergh W.A.M. Early trauma and familial risk in the development of the extended psychosis phenotype in adolescence. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;126(4):266–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2012.01857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung A.R., Yuen H.P., Berger G., Francey S., Hung T.C., Nelson B., Phillips L., McGorry P. Declining transition rate in ultra high risk (prodromal) services: dilution or reduction of risk? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2007;33(3):673–681. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yung A.R., Yuen H.P., McGorry P.D., Phillips L.J., Kelly D., Dell’Olio M., Francey S.M., Cosgrave E.M., Killackey E., Stanford C., Godfrey K., Buckby J. Mapping the onset of psychosis: the Comprehensive Assessment of At-Risk Mental States. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;39(11–12):964–971. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2005.01714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimbron J., Ruiz de Azua S., Khandaker G.M., Gandamaneni P.K., Crane C.M., González-Pinto A., Stochl J., Jones P.B., Pérez J. Clinical and sociodemographic comparison of people at high-risk for psychosis and with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2012;127(3):210–216. doi: 10.1111/acps.12000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]