Abstract

Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (ICBT) has been tested in many research trials, but to a lesser extent directly compared to face-to-face delivered cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials in which guided ICBT was directly compared to face-to-face CBT. Studies on psychiatric and somatic conditions were included. Systematic searches resulted in 13 studies (total N=1053) that met all criteria and were included in the review. There were three studies on social anxiety disorder, three on panic disorder, two on depressive symptoms, two on body dissatisfaction, one on tinnitus, one on male sexual dysfunction, and one on spider phobia. Face-to-face CBT was either in the individual format (n=6) or in the group format (n=7). We also assessed quality and risk of bias. Results showed a pooled effect size (Hedges' g) at post-treatment of −0.01 (95% CI: −0.13 to 0.12), indicating that guided ICBT and face-to-face treatment produce equivalent overall effects. Study quality did not affect outcomes. While the overall results indicate equivalence, there are still few studies for each psychiatric and somatic condition and many conditions for which guided ICBT has not been compared to face-to-face treatment. Thus, more research is needed to establish equivalence of the two treatment formats.

Keywords: Guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy, face-to-face therapy, anxiety and mood disorders, somatic disorders, meta-analysis

Internet-delivered psychological treatments have a relatively short history, with the first trials being conducted in late 1990s (1). A large number of programs have been developed, and trials have been conducted for a range of psychiatric and somatic conditions, mostly using Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy (ICBT) (2).

Many ICBT programs involve therapist guidance over encrypted e-mail, which to date, with a few exceptions (3), tend to generate larger effects than unguided programs (4). Many interventions are text-based and can be described as online bibliotherapy, even if streamed video clips, audio files and interactive elements are involved. These programs are typically comprised of 6-15 modules, which are text chapters corresponding to sessions in face-to-face therapy, and require little therapist involvement more than guidance and feedback on homework assignments (approximately 10-15 min per client and week). Other programs, such as Interapy (5), require more therapist input, as more text is exchanged between the therapist and the client. Finally, there are real time chat-based Internet treatments in which no therapist time is saved (6).

In terms of content, programs vary as well, but many tend to mirror face-to-face treatments in terms of content and length. Thus, for example, a program for depression can be 10 weeks long, with weekly modules mirroring sessions in manualized cognitive behavior therapy (CBT) (4), and the content may include psychoeducation, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, relapse prevention and home-work assignments (7).

While most studies have been on ICBT (8), there are also studies on other psychotherapeutic orientations, such as psychodynamic psychotherapy (9), and physical exercise (10). Different forms of ICBT have also been used, such as attention bias modification (11), problem solving therapy (12), and acceptance and commitment therapy (13). In addition to short-term effects indicating equivalence compared to therapist administered therapy (14-16), there are also a few long-term follow-up studies showing lasting effects over as much as 5 years post-treatment (17).

In spite of promising results in the controlled trials, an outstanding question is how well-guided ICBT compares against standard manualized face-to-face treatments. This was partly investigated in a meta-analysis by Cuijpers et al (18), who studied the effects of guided self-help on depression and anxiety vs. face-to-face psychotherapies. They included 21 studies with 810 participants and found no differences between the formats (Cohen's d=0.02). However, that meta-analysis mixed bibliotherapy and Internet interventions and focused on anxiety and depression only. Furthermore, new studies have emerged since that publication. Thus, there is a need for a systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on guided ICBT.

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy of guided ICBT compared to face-to-face CBT for psychiatric and somatic disorders. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies directly comparing the two treatment formats in randomized trials. We hypothesized that guided ICBT and face-to-face CBT would produce equivalent treatment effects.

METHODS

This was a systematic review and meta-analysis of original articles investigating the effect of guided ICBT compared to face-to-face treatments. To be included in the review, the original studies had to: a) compare therapist-guided ICBT to face-to-face treatment using a randomized controlled design; b) use interventions that were aimed at treatment of psychiatric or somatic disorders (not, for example, prevention or merely psychoeducation); c) compare treatments that were similar in content in both treatment conditions; d) investigate a form of ICBT where the Internet treatment was the main component and not a secondary complement to other therapies; e) investigate a form of full length face-to-face treatment; f) report outcome data from an adult patient sample; g) report outcomes in terms of assessment of symptoms of the target problem; and h) be written in English. We included only studies in which there was some therapist contact during the trial (7).

We calculated effect sizes based on the primary outcome measure at post-treatment in each study. If no primary outcome measure was specified in the original study, a validated measure assessing target symptoms of the clinical problem was used, following the procedures by Thomson and Page (19).

To identify studies, systematic searches in PubMed (Medline database) were conducted using various search terms related to psychiatric and somatic disorders, such as “depression”, “panic disorder”, “social phobia”, “social anxiety disorder”, “generalized anxiety disorder”, “obsessive-compulsive disorder”, “post-traumatic stress disorder”, “specific phobia”, “hypochondriasis”, “bulimia”, “tinnitus”, “erectile dysfunction”, “chronic pain”, or “fatigue”. These search terms relating to the clinical problem were combined with “Internet” or “computer”, or “computerized”, and the search filter “randomized controlled trial” was used.

In addition to the above, reference lists in the included studies were checked for potential additional studies. We did not search for unpublished studies. There were no restrictions regarding publication date. Searches were last updated in July 2013. We also consulted other databases (Scopus, Google Scholar and PsychInfo), and reference lists of recent studies and reviews on Internet interventions.

Two researchers read the abstracts independently and, in case of disagreement on inclusion, they discussed it amongst themselves or asked a third researcher for advice.

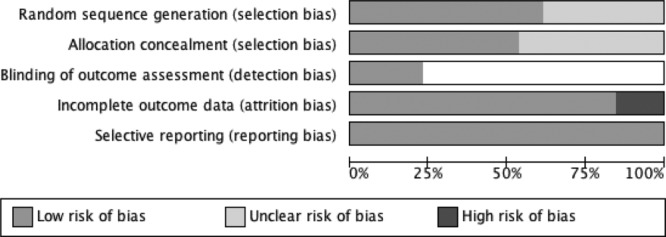

Each included study was assessed for quality using the criteria proposed by the Cochrane collaboration (20). Five dimensions were assessed: risk of selection bias due to the method for generating the randomization sequence; risk of selection bias in terms of allocation concealment, i.e., due to foreknowledge of the forthcoming allocations; detection bias in terms of blinding of outcome assessors; attrition bias due to incomplete outcome data; and reporting bias due to selective reporting of results. The criterion for performance bias relating to masking of participants was not used, as that form of masking is not possible in the types of treatments investigated in this review. On each dimension, the status of the studies was rated using the response options “low risk”, “high risk” or “unclear”. The alternative “unclear” was used when there was no data to assess the quality criterion in the original study. In studies using self-report, the criterion of blinding of outcome assessors was judged to be not applicable.

Data were analysed using Review Manager (RevMan) version 5.1.0 (20). In the main meta-analyses, we assessed the effect of guided ICBT compared to face-to-face treatment using the standardized mean difference at post-treatment (Hedges' g) as outcome, meaning that the difference between treatments was divided by the pooled standard deviation. If both intention-to-treat and per-protocol data were presented, the former estimate was used in the meta-analysis. Estimates of treatment effects were conducted both using all included studies and separately for each clinical disorder (e.g., depression). Potential differences in dropout rates between guided ICBT and face-to-face treatment were analysed using meta-analytic logistic regression.

All pooled analyses were carried out within a random effects model framework, assuming variation in true effects in the included studies and accounting for the hypothesized distribution of effects (21,22). Studies were assessed for heterogeneity using χ2 and I2 tests, where an estimate above 40% on the latter test suggests presence of heterogeneity (21). In addition, forest plots were inspected to assess variation in effects across studies. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess whether study quality was related to outcome, by comparing studies judged as having a low risk of bias on all five quality criteria dimensions with the other studies (i.e., those assessed as “unclear” or “high risk” on at least one quality criterion). Publication bias was investigated using funnel plots.

Power calculations were conducted as suggested by Borenstein et al (22) and showed that, in order to have a power of 80% to detect a small effect size (d=0.3), given an alpha-level of 0.05, 14 studies with an average of 25 participants in each treatment arm were needed.

RESULTS

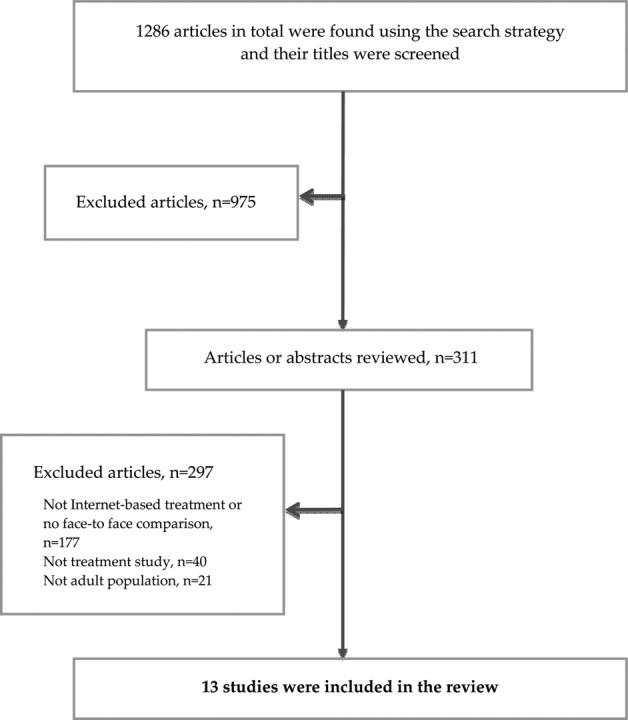

Of 1,286 screened studies, 13 (total N=1053) met all review criteria and were included in the analysis. Figure 1 displays the study inclusion process. All the 13 studies investigated guided ICBT against some form of CBT (individual format, n=6 and group format, n=7). In terms of conditions studied, three targeted social anxiety disorder (23–25), three panic disorder (26–28), two depressive symptoms (29,30), two body dissatisfaction (31,32), one tinnitus (33), one male sexual dysfunction (34), and one spider phobia (35). The total number of participants was 551 in guided ICBT and 502 in the face-to-face condition.

Figure 1.

Study inclusion process

The studies were conducted by eight independent research groups and carried out in Australia, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, or the U.S.. The smallest study had 30 participants and the largest 201. Seven studies recruited participants solely through self-referral, while the remainder included participants from clinical samples or using a mix of self-referral and clinical recruitment. All studies were published between 2005 and 2013. The characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies

| Study | Disorder | N INT | N FTF | Outcome evaluation | Mean (SD) INT pre | Mean (SD) INT post | Mean (SD) FTF pre | Mean (SD) FTF post | Quality* | Dropout rate | ITT | Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hedman et al (25) | Social anxiety disorder | 62 | 64 | LSAS | 68.4 (21.0) | 39.4 (19.9) | 71.9 (22.9) | 48.5 (25.0) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 12% | Yes | Mixed |

| Andrews et al (23) | Social anxiety disorder | 23 | 14 | SIAS | 54.5 (12.4) | 44.0 (15.9) | 57.8 (43.9) | 43.9 (18.7) | Unclear/high risk on at least one criterion | 32% | Yes | Clinical |

| Botella et al (24) | Social anxiety disorder | 62 | 36 | FPSQ | 53.3 (14.3) | 39.7 (15.5) | 50.5 (11.9) | 39.3 (13.0) | Unclear/high risk on at least one criterion | 55% | Yes | Mixed |

| Carlbring et al (27) | Panic disorder | 25 | 24 | BSQ | 48.7 (11.7) | 31.8 (11.6) | 52.6 (10.8) | 31.3 (9.1) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 12% | Yes | Self-referred |

| Bergström et al (26) | Panic disorder | 53 | 60 | PDSS | 14.1 (4.3) | 6.3 (4.7) | 14.2 (4.0) | 6.3 (5.6) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 18% | Yes | Mixed |

| Kiropoulous et al (28) | Panic disorder | 46 | 40 | PDSS | 14.9 (4.4) | 9.9 (5.9) | 14.8 (4.0) | 9.2 (5.7) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 0% | Yes | Self-referred |

| Spek et al (29) | Depressive symptoms in elderly | 102 | 99 | BDI | 19.2 (7.2) | 12.0 (8.1) | 17.9 (10.0) | 11.4 (9.4) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 39% | Yes | Self-referred |

| Wagner et al (30) | Depressive symptoms | 32 | 30 | BDI | 23.0 (6.1) | 12.4 (10.0) | 23.4 (7.6) | 12.3 (8.8) | Unclear/high risk on at least one criterion | 15% | Yes | Self-referred |

| Gollings & Paxton (31) | Body dissatisfaction | 21 | 19 | BSQ | 129.1 (27.3) | 98.4 (35.6) | 140.8 (37.2) | 109.6 (47.7) | Unclear/high risk on at least one criterion | 17.5% | Yes | Self-referred |

| Paxton et al (32) | Body dissatisfaction, disordered eating | 42 | 37 | BSQ | 134.3 (22.5) | 116.8 (35.9) | 143.3 (28.9) | 105.8 (34.0) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 26% | Yes | Self-referred |

| Kaldo et al (33) | Tinnitus | 26 | 25 | TRQ | 26.4 (15.6) | 18.0 (16.2) | 30.0 (18.0) | 18.6 (17.0) | Low risk of bias on all criteria | 14% | Yes | Mixed |

| Schover et al (34) | Male sexual dysfunction | 41 | 40 | IIEF | 27.4 (17.3) | 31.3 (20.4) | 26.4 (18.2) | 34.4 (22.2) | Unclear/high risk on at least one criterion | 20% | Yes | Mixed |

| Andersson et al (35) | Specific phobia (spider) | 15 | 15 | BAT | 6.2 (2.6) | 10.5 (1.5) | 7.3 (1.6) | 11.1 (1.2) | Unclear/high risk on at least one criterion | 10% | No | Self-referred |

aFive dimensions of quality were assessed (see text); in this table, the criterion of blinding of outcome assessment is disregarded in the studies assessing outcome only through self-report INT – guided Internet-based treatment, FTF – face-to-face treatment, ITT – intention-to-treat analysis, LSAS – Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale, SIAS – Social Interaction Anxiety Scale, FPSQ – Fear of Public Speaking Questionnaire, BSQ – Body Sensation Questionnaire, PDSS – Panic Disorder Severity Scale, BDI – Beck Depression Inventory, TRQ – Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire, IIEF – International Index of Erectile Function, BAT – Behavioural Approach Test

When blinding of outcome assessment was included, only three studies were judged as having low risk of bias on all five quality dimensions (25,26,28). When that criterion was disregarded in the studies assessing outcome only through self-report, 7 of 13 studies were judged as having low risk of bias on all quality dimensions. Figure 2 displays the averaged risk of bias in the included studies.

Figure 2.

Estimated risk of bias across all included studies

In terms of dropout, meta-analytic logistic regression showed no significant difference between the two treatment formats (OR=0.79; 95% CI: 0.57-1.09), indicating that dropout did not systematically favour one treatment over the other. Tests of heterogeneity did not demonstrate significant differences in effects across treatments (χ2=9.91; I2=0%; p=0.62).

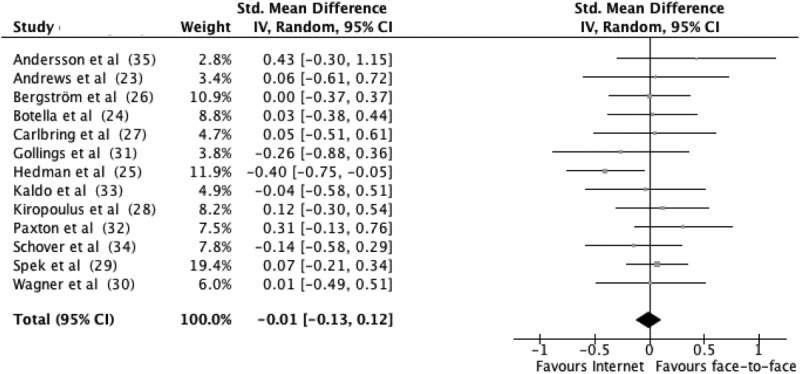

A forest plot presenting effect sizes (g) of each study as well as the pooled between-group effect size of all studies is presented in Figure 3. An effect size estimate below 0 favours guided ICBT, while an effect size above 0 represents larger effects for face-to-face CBT. The pooled between-group effect size (g) at post-treatment across all 13 studies was −0.01 (95% CI: −0.13 to 0.12), showing that guided ICBT and face-to-face treatment produced equivalent overall effects.

Figure 3.

Forest plot displaying effect sizes of studies comparing guided Internet-based treatment with face-to-face treatment

In the three studies targeting social anxiety disorder (23–25), the pooled between-group effect size (g) was −0.16 (95% CI: −0.47 to 0.16), in favour of guided ICBT but indicating equivalent effects. In the three studies targeting panic disorder (26-28), the effect size was 0.05 (95% CI: −0.20 to 0.30), in line with the notion of equivalent effects. In the two studies targeting depressive symptoms (29,30), the effect size was 0.05 (95% CI: −0.19 to 0.30), showing equivalent effects for this condition as well.

In the two studies targeting body dissatisfaction (31,32), the effect size was 0.07 (95% CI: −0.49 to 0.62), again showing largely equivalent effects. In the only study targeting tinnitus (36), the effect size was −0.04 (95% CI: −0.58 to 0.51), suggesting no difference between the formats for this condition as well. In the only study targeting male sexual dysfunction (34), using a clinical sample of patients that had been treated for prostate cancer, the effect size was −0.14 (95% CI: −0.58 to 0.29), which is a small effect again in slight favour of ICBT. In the only study targeting spider phobia (35), the effect size was 0.43 (95% CI: −0.30 to 1.15), in favour of face-to-face treatment, but given the small size of the study not significant.

In order to estimate whether there was an association of study quality and treatment effects, subgroup analyses were conducted. In the three studies judged to have low risk of bias on all five quality criteria, the pooled effect size (g) was −0.11 (95% CI: −0.42 to 0.21), while it was 0.05 (95% CI: −0.10 to 0.19) for the other ten studies, suggesting that study quality did not affect outcomes significantly.

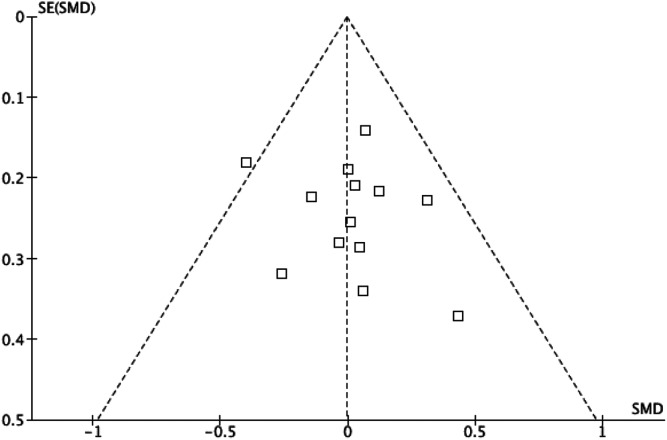

Figure 4 presents a funnel plot relating effect sizes on the primary outcome of the studies to the standard errors of the estimates. Effect sizes were evenly distributed around the averaged effect. Of specific interest, the lower right section of the funnel plot is not devoid of studies, suggesting that there is no major bias of the pooled effect estimate due to unpublished small studies with results favouring face-to-face treatment.

Figure 4.

Funnel plot to assess for publication bias by relating effect sizes of the studies to standard errors. SE – standard error, SMD – standardized mean difference (Cohen's d)

DISCUSSION

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to collect and analyse studies in which guided ICBT had been directly compared with face-to-face CBT. Altogether, the findings are clear in that the overall effect for the main outcomes was close to zero, indicating that the two treatment formats are equally effective in social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, depressive symptoms, body dissatisfaction, tinnitus, male sexual dysfunction, and spider phobia, when analysed as an aggregated cohort.

Thus, the present meta-analytic review mirrors the findings by Cuijpers et al (18), who found no differences between guided self-help and face-to-face therapies. Interestingly, there is only a minor overlap between that meta-analysis and the present one. We included the studies by Spek et al (29) and Botella et al (24), as they involved therapist contact in association with inclusion (but not during treatment). We did not include a study (included in Cuijpers et al's meta-analysis) that was judged to compare two forms of ICBT rather than ICBT vs. face-to-face treatment (37).

While there were relatively few studies on each condition, the overall number of studies and number of participants gave us power to detect differences of importance between the formats. There was a low risk of bias, including publication bias, but many individual studies were much underpowered to detect differences, and for each of the included conditions there were few studies and sometimes only one.

The results of this meta-analysis are thought-provoking both from a theoretical and practical point of view. In terms of theories about change in psychotherapeutic interventions, the results suggest that the role of a face-to-face therapist may not be as crucial as suggested in the literature (38) to generate large treatment effects. Even if factors such as therapeutic alliance are established in guided ICBT (39), they are rarely important for outcome. Indeed, understanding what makes ICBT work is a challenge for future research, as only a few studies to date have investigated mediators of outcome (e.g., 40,41).

From a practical point of view, the findings call for research on treatment preferences and effectiveness in real life settings, as most studies in this review involved self-referred participants recruited via advertisements. There are studies on treatment acceptability of ICBT showing that patient tend to appreciate the ICBT format (42–44), but also one study reporting the opposite (45). When it comes to effectiveness, there are now at least four controlled trials and eight open studies showing that ICBT works in regular clinical settings (46). However, controlled trials such as the ones reviewed in this meta-analysis all require that participants consent to being randomized to either ICBT or face-to-face treatment, a requirement that limits the generalizability of the results.

The present meta-analysis has several strengths, such as a consistent outcome across studies regarding efficacy of guided ICBT compared to face-to-face CBT, the relatively high quality of the trials included, little heterogeneity and no indication of publication bias. However, there are also limitations. First, the included studies differed substantially in terms of treatment content, not so much within studies as between ICBT programs. We endorsed a broad definition of CBT, but it would of course have been preferable to have many studies on the same program, as is the case in reviews of cognitive therapy for depression (47). Second, we compared against different formats of face-to-face therapy and it could be argued that group CBT is a suboptimal comparison (48), at least when it comes to patient preferences. Third, we analysed the primary outcome measures in the trials and did not include secondary outcomes. Indeed, the heterogeneity of clinical conditions included can be viewed as a problem on its own, but we cannot at this stage and with very few studies for each condition conclude that guided ICBT and face-to-face therapy are equally effective on all outcomes. For example, there are very few studies on knowledge acquisition following CBT and even fewer on ICBT (49), and this can be something that differs between the therapy formats (in particular in the long run). In addition, patient characteristics have not been taken into account. This is potentially important, since there are studies suggesting that different predictors of outcome (e.g., agoraphobic avoidance) are relevant when comparing face-to-face versus Internet treatment. Fourth, we only included studies on adult samples. However, a study by Spence et al (50) on adolescents is clearly in line with our findings, suggesting equivalence. Finally, we did not analyse long-term effects of the treatments. This is a possible area for future research, as the type of trials included here has the advantage that randomization can be maintained for long time periods.

ICBT has only been around for a short time and is still developing rapidly (51). A recent change is the use of mobile smart phones in treatment, and it is likely that smart phone applications and ICBT will blend in with face-to-face treatment in the near future. Finally, while we performed this review in the form of a study-level meta-analysis, there is an emerging trend to instead conduct patient-level meta-analyses with primary data (52).

In conclusion, guided ICBT has the promise to be an effective, and potentially cost-effective, alternative and complement to face-to-face therapy. More studies are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn, but the findings to date, including this meta-analysis, clearly show that guided ICBT is a treatment for the future.

Acknowledgments

G. Andersson acknowledges Linköping University, the Swedish Science Foundation and Forte for financial support.

References

- 1.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Ljótsson B, et al. Guided Internet-based CBT for common mental disorders. J Contemp Psychother. 2013;43:223–33. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hedman E, Ljótsson B, Lindefors N. Cognitive behavior therapy via the Internet: a systematic review of applications, clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2012;12:745–64. doi: 10.1586/erp.12.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Titov N, Dear BF, Johnston L, et al. Improving adherence and clinical outcomes in self-guided internet treatment for anxiety and depression: randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Berger T, et al. What makes Internet therapy work? Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38(S1):55–60. doi: 10.1080/16506070902916400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lange A, Rietdijk D, Hudcovicova M, et al. Interapy: a controlled randomized trial of the standardized treatment of posttraumatic stress through the Internet. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:901–9. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessler D, Lewis G, Kaur S, et al. Therapist-delivered internet psychotherapy for depression in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:628–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson R, Andersson G. Internet-based psychological treatments for depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2012;12:861–70. doi: 10.1586/ern.12.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersson G. Using the internet to provide cognitive behaviour therapy. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:175–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johansson R, Ekbladh S, Hebert A, et al. Psychodynamic guided self-help for adult depression through the Internet: a randomised controlled trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e38021. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ström M, Uckelstam C-J, Andersson G, et al. Internet-delivered therapist-guided physical activity for mild to moderate depression: a randomized controlled trial. PeerJ. 2013;1:e178. doi: 10.7717/peerj.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlbring P, Apelstrand M, Sehlin H, et al. Internet-delivered attention training in individuals with social anxiety disorder – a double blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Twisk J, et al. Internet-based treatment for adults with depressive symptoms: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2008;10:e44. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buhrman M, Skoglund A, Husell J, et al. Guided Internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain patients: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2013;51:307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Andersson G, Cuijpers P. Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: a meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:196–205. doi: 10.1080/16506070903318960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Andrews G, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, et al. Computer therapy for the anxiety and depressive disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cuijpers P, van Straten A-M, Andersson G. Internet-administered cognitive behavior therapy for health problems: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2008;31:169–77. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9144-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hedman E, Furmark T, Carlbring P, et al. Five-year follow-up of internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for social anxiety disorder. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13:e39. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuijpers P, Donker T, van Straten A, et al. Is guided self-help as effective as face-to-face psychotherapy for depression and anxiety disorders? A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Psychol Med. 2010;40:1943–57. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710000772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomson AB, Page LA. Psychotherapies for hypochondriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;((4)):CD006520. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006520.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011.

- 21.Crowther M, Lim W, Crowther MA. Systematic review and meta-analysis methodology. Blood. 2010;116:3140–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-280883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, et al. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andrews G, Davies M, Titov N. Effectiveness randomized controlled trial of face to face versus Internet cognitive behaviour therapy for social phobia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:337–40. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.538840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Botella C, Gallego MJ, Garcia-Palacios A, et al. An Internet-based self-help treatment for fear of public speaking: a controlled trial. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:407–21. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2009.0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedman E, Andersson G, Ljótsson B, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy vs. cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18001. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bergström J, Andersson G, Ljótsson B, et al. Internet-versus group-administered cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder in a psychiatric setting: a randomised trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:54. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-10-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carlbring P, Nilsson-Ihrfelt E, Waara J, et al. Treatment of panic disorder: live therapy vs. self-help via Internet. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:1321–33. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kiropoulos LA, Klein B, Austin DW, et al. Is internet-based CBT for panic disorder and agoraphobia as effective as face-to-face CBT? J Anxiety Disord. 2008;22:1273–84. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spek V, Nyklicek I, Smits N, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for subthreshold depression in people over 50 years old: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1797–806. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wagner B, Horn AB, Maercker A. Internet-based versus face-to-face cognitive-behavioral intervention for depression: a randomized controlled non-inferiority trial. J Affect Disord. 2014;152-154:113–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gollings EK, Paxton SJ. Comparison of internet and face-to-face delivery of a group body image and disordered eating intervention for women: a pilot study. Eat Disord. 2006;14:1–15. doi: 10.1080/10640260500403790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paxton SJ, McLean SA, Gollings EK, et al. Comparison of face-to-face and internet interventions for body image and eating problems in adult women: an RCT. Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40:692–704. doi: 10.1002/eat.20446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaldo V, Levin S, Widarsson J, et al. Internet versus group cognitive-behavioral treatment of distress associated with tinnitus. A randomised controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2008;39:348–59. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schover LR, Canada AL, Yuan Y, et al. A randomized trial of internet-based versus traditional sexual counseling for couples after localized prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2012;118:500–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Andersson G, Waara J, Jonsson U, et al. Internet-based self-help vs. one-session exposure in the treatment of spider phobia: a randomized controlled trial. Cogn Behav Ther. 2009;38:114–20. doi: 10.1080/16506070902931326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaldo V, Levin S, Widarsson J, et al. Internet versus group cognitive-behavioral treatment of distress associated with tinnitus: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Ther. 2008;39:348–59. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tillfors M, Carlbring P, Furmark T, et al. Treating university students with social phobia and public speaking fears: Internet delivered self-help with or without live group exposure sessions. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:708–17. doi: 10.1002/da.20416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wampold BE. The great psychotherapy debate. Models, methods, and findings. Mahaw: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersson G, Paxling B, Wiwe M, et al. Therapeutic alliance in guided Internet-delivered cognitive behavioral treatment of depression, generalized anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:544–50. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hedman E, Andersson E, Andersson G, et al. Mediators in Internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for severe health anxiety. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77752. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hesser H, Zetterqvist Westin V, Andersson G. Acceptance as mediator in Internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive behavior therapy for tinnitus. J Behav Med. 2014;37:756–67. doi: 10.1007/s10865-013-9525-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wootton BM, Titov N, Dear BF, et al. The acceptability of Internet-based treatment and characteristics of an adult sample with obsessive compulsive disorder: an Internet survey. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20548. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spence J, Titov N, Solley K, et al. Characteristics and treatment preferences of people with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder: an internet survey. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21864. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gun SY, Titov N, Andrews G. Acceptability of Internet treatment of anxiety and depression. Australas Psychiatry. 2011;19:259–64. doi: 10.3109/10398562.2011.562295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohr DC, Siddique J, Ho J, et al. Interest in behavioral and psychological treatments delivered face-to-face, by telephone, and by internet. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:89–98. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9203-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersson G, Hedman E. Effectiveness of guided Internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy in regular clinical settings. Verhaltenstherapie. 2013;23:140–8. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, et al. A meta-analysis of cognitive behavior therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison to other treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:376–85. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison N. Group cognitive therapy: treatment of choice or suboptimal option? Behav Cogn Psychother. 2001;29:311–32. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Andersson G, Carlbring P, Furmark T, et al. Therapist experience and knowledge acquisition in Internet-delivered CBT for social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. PloS One. 2012;7:e37411. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Spence SH, Donovan CL, March S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of online versus clinic-based CBT for adolescent anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:629–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Andersson G, Titov N. Advantages and limitations of Internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:4–11. doi: 10.1002/wps.20083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bower P, Kontopantelis E, Sutton AP, et al. Influence of initial severity of depression on effectiveness of low intensity interventions: meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ. 2013;346:f540. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]