Abstract

Background

Neuroacanthocytosis (NA) syndromes are a group of rare diseases characterized by the presence of acanthocytes and neuronal multisystem pathology, including chorea-acanthocytosis (ChAc), McLeod syndrome (MLS), Huntington's disease-like 2 (HDL-2), and pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN). China has the largest population in the world, which makes it a good location for investigating rare diseases like NA.

Methods

We searched Medline, ISI Proceedings, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, and Wanfang Data for literature published through December 31, 2013 for all the published Chinese NA case reports and extracted the clinical and laboratory findings.

Results

A total of 42 studies describing 66 cases were found to be eligible for inclusion. Age of symptom onset ranged from 5 to 74 years. The most common findings included hyperkinetic movements (88%), orofacial dyskinesia (80%), dystonia (67%), and dysarthria (68%), as well as caudate atrophy or enlarged lateral ventricles on neuroimaging (64%), and elevated creatine kinase (52%). Most cases were not confirmed by any specific molecular tests. Only two cases were genetically studied and diagnosed as ChAc or MLS.

Discussion

In view of the prevalence of NA syndromes in other countries, the number of patients in China appears to be underestimated. Chinese NA patients may benefit from the establishment of networks that offer specific diagnoses and care for rare diseases.

Keywords: Neuroacanthocytosis, chorea-acanthocytosis, McLeod syndrome, neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation, China

Introduction

Neuroacanthocytosis (NA), an umbrella term for a group of rare diseases characterized by misshapen erythrocytes (acanthocytes) and neuronal multisystem pathology, includes diseases such as autosomal recessive chorea-acanthocytosis (ChAc), X-linked McLeod syndrome (MLS), Huntington's disease-like 2 (HDL-2), and pantothenate kinase-associated neurodegeneration (PKAN).1 NA was first described as Levine-Critchley syndrome on the basis of reports by Levine and Critchley in two families from North America in the 1960s.2,3 Although the clinical manifestations of NA resemble Huntington's disease (HD), there are clear differences in the mode of inheritance and neuropathological changes. In the last decade, molecular and protein methods have rapidly developed for the diagnosis of different NA subtypes.

China has the largest population in the world (1.35 billion), making it a suitable location for investigating rare diseases like NA. The first Chinese NA literature is a translation of the paper by Sakai et al in 1981.4,5 Over the last 30 years, few Chinese NA case reports have been published.6–53 Moreover, communication with foreign scholars was limited because most of the reports were published in Chinese. ChAc has been reported in many different ethnic groups, and the relatively high prevalence in Japan appears to be due to a founder mutation.54 In light of the similar East Asian backgrounds in the two countries, we suspect that in China NA syndromes are underdiagnosed, leading to a significant underestimation of the prevalence.

In the current study, we systematically reviewed Chinese NA epidemiology by searching for published NA cases. We aimed to summarize the features of Chinese NA cases in comparison with other countries and identify potential reasons for underestimation.

Methods

We searched Medline (from January 1, 1949 to December 31, 2013), ISI Proceedings (January 1, 1990 to December 31, 2013), China National Knowledge Infrastructure (http://www.cnki.net, from January 1, 1979 to December 31, 2013) and Wanfang Data (http://www.wanfangdata.com.cn, from January 1, 1984 to December 31, 2013). The search terms in English and their Chinese equivalents included “neuroacanthocytosis,” “chorea-acanthocytosis,” “McLeod syndrome,” “choreoacanthocytosis,” “hereditary acanthocytosis syndrome,” and “Levine-Critchley syndrome.” We also tried to identify cases from cross-references between papers. We only included those case reports where an explicit diagnosis of NA had been made by the original authors. For inclusion, patients had to be of Chinese origin and diagnosed in China. We extracted information on geographical origin, sex, age of onset, and clinical and laboratory findings from each case.

Results

We identified a total of 48 publications with 66 cases reported (37 males and 29 females) (Table 1). All of these patients had been diagnosed with NA, ChAc, or MLS by the reporting physicians. Only one ChAc case was confirmed by a genetic test (VPS13A gene), and no cases were confirmed by Western blot for the protein chorein that is affected in ChAc.55 An elevated proportion of acanthocytes in blood samples was regarded as the most important diagnostic clue by Chinese physicians. However, heterogeneous methods for detecting acanthocytosis were used in the different reports, thus affecting the accuracy of the test. Only one MLS case, from Hong Kong, was reported with a corresponding XK gene mutation.

Table 1. Baseline Information on NA Cases from China.

| Ref. | Place of Diagnosis | Year of Publication | No. Cases | Sex | AOO | Initial Symptoms | Acanthocytes (%) | Reported Diagnosis | Our Diagnostic Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | Anhui | 1984 | 2 | 2M | 19, 27 | Orof. (1), MD/Orof. (1) | 23%, 3% | ChAc | |

| 7 | Anhui | 1987 | 2 | 2M | 26, 32 | DYA (1), MD/Orof. (1) | 10% | ChAc | |

| 8 | Anhui | 2000 | 2 | 2F | 45, 46 | MD (1), PSY (1) | 35%, 17% | ChAc | |

| 9 | Anhui | 2004 | 1 | 1M | 39 | Orof./MD | 4–7% | ChAc | |

| 10 | Beijing | 2005 | 1 | 1F | n.a. | MD | 4% | ChAc | |

| 11–14 | Beijing | 2005, 2012 | 8 | 2M, 6F | 10–35 | Orof. (4), MD (3), PN (1) | >10% | NA | |

| 15 | Beijing | 2007 | 2 | 2M | 27, 37 | MD (1), EPI (1) | 15–25% | ChAc | |

| 16 | Beijing | 2010 | 1 | 1M | 11 | n.a. | 30% | NA | |

| 17, 18 | Beijing | 2013 | 1 | 1M | 42 | MD/Orof. | >40% | NA | NBIA |

| 19 | Beijing | 2013 | 3 | 3M | 16–43 | MD, Orof. (2), BP (1) | >30% | NA | |

| 20 | Chongqing | 2013 | 1 | 1F | 33 | DYA/WI/MD/Orof. | >3% | ChAc | |

| 21 | Gansu | 2009 | 1 | 1M | 20 | MD | n.a. | NA | |

| 22 | Guangdong | 2003 | 1 | 1M | 42 | Orof. | 30% | ChAc | |

| 23 | Helongjiang | 1989 | 1 | 1F | 36 | DYA/Orof. | 15–20% | ChAc | |

| 24 | Helongjiang | 1989 | 2 | 1M, 1F | 9, 11 | Orof. | 56%, 28% | ChAc | NBIA |

| 25 | Helongjiang | 1990 | 1 | 1F | 38 | Orof. | 40–50% | ChAc | |

| 26,27 | Helongjiang | 2003, 2007 | 1 | 1F | 35 | Orof. | 28.5% | ChAc | |

| 28 | He’nan | 2005 | 1 | 1F | 30 | Orof./EPI | 25% | NA | |

| 29 | He’nan | 2011 | 2 | 1M, 1F | 30, 31 | MD (1), Orof. (1) | 35%, 25% | ChAc | |

| 30 | He’nan | 2012 | 1 | 1M | 43 | MD | 11%–15% | ChAc | |

| 31 | Hong Kong | 2013 | 1 | 1M | 47 | GD/MD | 16% | MLS* | |

| 32 | Hubei | 2007 | 1 | 1F | 28 | Orof. | 6–8% | NA | |

| 33 | Hubei | 2013 | 1 | 1M | 37 | n.a. | n.a. | NA | |

| 34 | Hu’nan | 2013 | 1 | 1F | 24 | n.a. | n.a. | ChAc* | |

| 35 | Jiangsu | 2012 | 1 | 1F | 20 | MD/Orof. | 7.8% | ChAc | |

| 36 | Liaoning | 1989 | 1 | 1M | 28 | Orof. | 84% | ChAc | |

| 37 | Neimenggu | 2005 | 1 | 1M | 32 | EPI | 10% | ChAc | |

| 38 | Neimenggu | 2007 | 1 | 1M | 34 | MD | 10% | ChAc | |

| 39 | Neimenggu | 2012 | 1 | 1M | 38 | Orof. | 5% | ChAc | |

| 40 | Qinghai | 2006 | 1 | 1F | 24 | MD | 18% | NA | |

| 41 | Shandong | 2001 | 3 | 3F | 20–21 | MD | 12% | NA | |

| 42 | Shandong | 2013 | 1 | 1M | 32 | MD/Orof. | 10% | ChAc | |

| 43 | Shandong | 2013 | 3 | 2M, 1F | 26–50 | MD/Orof. (1), PSY (2) | >30% | ChAc | |

| 44 | Shanghai | 2008 | 1 | 1F | 33 | MD/Orof. | 7–8% | ChAc | |

| 45 | Shanghai | 2008 | 1 | 1M | 5 | DYT | >30% | NA | NBIA |

| 46 | Shanghai | 2010 | 1 | 1F | 55 | WI | >20% | NA | |

| 47 | Shanghai | 2012 | 3 | 2M, 1F | 31–74 | MD (1), GD (2) | 10–28% | NA | |

| 48 | Shanghai | 2013 | 1 | 1M | 46 | WI, DYA | 44.9% | NA | |

| 49, 50 | Shanxi | 2004 | 3 | 2M, 1F | 26–30 | EPI (2), Orof. (1) | 12–30% | ChAc | |

| 51 | Sichuan | 2012 | 2 | 2M | 17, 18 | Orof. (2) | 6%, 6% | ChAc | |

| 52 | Sichuan | 1988 | 1 | 1M | 25 | Orof. | 4% | ChAc | |

| 53 | Taiwan | 2006 | 1 | 1F | 31 | MD | 49% | NA |

Abbreviations: *, Gene Confirmed; AOO, Age of Onset; BP, Blepharospasm; ChAc, Chorea-Acanthocytosis; DYA, Dysarthria; DYT, Dystonia; EPI, Epilepsy; F, Female; GD, Gait Disturbance; M, Male; MD, Movement Disorders (Chorea or Hyperkinetic Movements); MLS, McLeod Syndrome; n.a., Not Available; NA, Neuroacanthocytosis; NBIA, Neurodegeneration with Brain Iron Accumulation (Type I/Type II); No., Number; Orof., Orofacial Dyskinesia; PN, Parkinsonism; PSY, Psychiatric Symptoms; Ref., Reference; WI, Walking Instability.

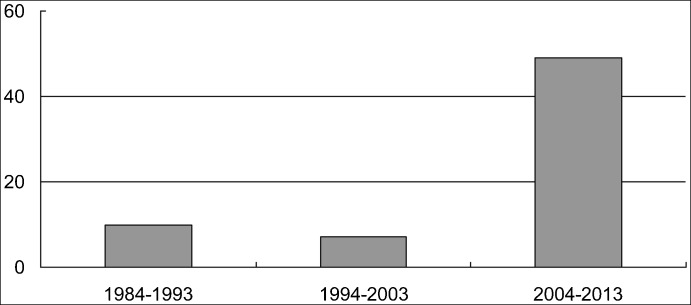

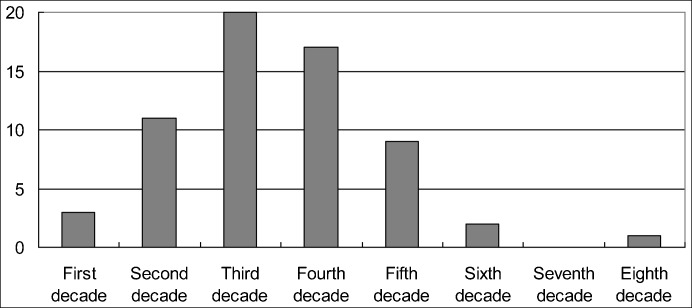

In the most recent decade (2004 to 2013) the number of reported cases increased dramatically, being about five times the number documented from 1984 to 1993, and seven times the number documented between 1994 and 2003 (Figure 1). No video recordings were published with the publications reviewed in this study. With respect to the geographic distribution, all cases originated from 19 Chinese provinces, with 16 cases reported in Beijing, 7 cases from Anhui, and 7 cases from Shangdong as the top 3 provinces. The ages of onset ranged from 5 to 74 years and were concentrated in the third and fourth decades (n = 37, 56%) (Figure 2). Common initial symptoms were orofacial dyskinesia (n = 27, 41%) and hyperkinetic limb or trunk movements (n = 27, 41%). Dysarthria, epilepsy, gait disturbance, parkinsonism, and psychiatric symptoms were also reported as the initial symptoms. Diagnoses were mainly made based on the presence of a hyperkinetic movement disorder, elevated acanthocytes in the blood, the pattern of inheritance (recessive), and the exclusion of other possible diseases, such as HD.

Figure 1. The Number of Chinese NA Cases Reported in the Last Three Decades.

In the most recent decade (2004 to 2013) the number of reported cases increased dramatically, being about five times the number documented from 1984 to 1993, and seven times the number

Figure 2. The Distribution of Ages of Onset in Chinese NA Cases.

Among the 63 cases with clearly documented ages of onset, most were concentrated in the third and fourth decades (ages 21 to 40).

Figure 3 summarizes the clinical and laboratory findings reported in Chinese NA cases. The most frequent findings were hyperkinetic movements (n = 58, 88%). Orofacial dyskinesia was reported in 53 patients (80%). In addition, dystonia (n = 44, 67%) and dysarthria (n = 45, 68%) were also common. 10 patients (15%) suffered from epilepsy, and 22 patients (33%) exhibited psychiatric symptoms.

Figure 3. Clinical and Laboratory Findings in Chinese NA Patients (n = 66).

Abbreviations: CK, Creatine Kinase Elevation; IMG, Caudate Atrophy or Enlarged Lateral Ventricles on Neuroimaging; LEE, Liver Enzyme Elevation; MD, Movement Disorders (Chorea or Hyperkinetic Movements); NA, Neuroacanthocytosis; Orof., Orofacial Dyskinesia; PSY, Psychiatric Symptoms.

With respect to clinical investigations, caudate atrophy or enlarged lateral ventricles on neuroimaging (n = 42, 64%) and elevated CK (n = 34, 52%) were the most frequently reported.

Discussion

Hyperkinetic movements and orofacial dyskinesia were the most common symptoms in this series of Chinese NA cases, reported in 88% and 80% of patients, respectively. This is consistent with the literature in that orofacial dyskinesia appears to be a relatively specific NA symptom, characterized by tongue protrusion and feeding dystonia. Chorea was typical in the early stages and tended to progress to parkinsonism. Parkinsonism has occasionally been reported to be the initial symptom.56,57

We found lower proportions of patients with epilepsy (15%) and psychiatric symptoms (33%) than reported in the literature (50% and 66%, respectively).58,59

In our study, 52% of Chinese NA cases had elevated CK levels, while only 11% of cases exhibited liver enzyme elevation, suggesting that CK is probably a more useful biomarker for NA than acanthocytes or liver enzymes, as is consistent with the literature. However, values within normal ranges are likely to have been omitted in many publications, thus, we could not accurately calculate the proportion of patients with normal CK or liver enzyme levels.58

The number of cases reported for 1994–2003 is relatively low in comparison to the numbers for 1984–1993 and 2004–2013. It is possible that some cases were not reported because they were not recognized or were not thought to be of interest after awareness was originally raised regarding the syndrome. It is important to determine whether these low rates of reported cases are due to publication bias and incomplete documentation, or whether these discrepancies are due to ethnic differences.

The clinical diagnosis of NA in China is mainly based on clinical manifestations and an elevated proportion of acanthocytes in the blood, as well as the exclusion of other possible diseases. Previously this was the standard diagnostic evaluation worldwide (e.g., a Chinese patient diagnosed with ChAc in Singapore in the 1980s).60 Recently, however, there have been clear NA cases without acanthocyte elevation.61

The other forms of NA, such as HDL-2 and PKAN, have not yet been reported in China. However, as some of the NA cases reported had an early age of onset (Table 1), it is likely that PKAN was the correct diagnosis.

With regard to MLS, only one Chinese case has been identified, indicating that it is probably underdiagnosed. Without specific molecular testing, an accurate diagnosis for presumed NA cases is impossible. As an alternative to DNA analyses, chorein detection by Western blot is an inexpensive method for diagnosing ChAc, and Kell antigen phenotyping can be performed to diagnose MLS.55,62

In view of the prevalence of NA syndromes in countries such as the United Kingdom and Germany (approximately 3 in 10 million), the number of NA patients in China should be at least 400 and appears to be underestimated. In addition to raising awareness among Chinese neurologists, the absence of specific molecular tests is the main diagnostic flaw that needs to be addressed. A Chinese network of NA collaboration may improve the diagnosis and treatment for patients affected by this group of incapacitating hyperkinetic movements.

Footnotes

Funding: None.

Financial Disclosures: None.

Conflict of Interests: The authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Walker RH, Jung HH, Danek A. Neuroacanthocytosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2011;100:141–151. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-52014-2.00007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine IM, Estes JW, Looney JM. Hereditary neurological disease with acanthocytosis. A new syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1968;19:403–409. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1968.00480040069007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Critchley EM, Clark DB, Wikler A. An adult form of acanthocytosis. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1967;92:132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou XF. Choreoacanthocytosis. Clues to clinical diagnosis (in Chinese) J Chin PLA Postgrad Med Sch. 1981;S2:5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sakai T, Mawatari S, Iwashita H, Goto I, Kuroiwa Y. Choreoacanthocytosis. Clues to clinical diagnosis. Arch Neurol. 1981;38:335–338. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1981.00510060037003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang RM, Bao YZ, Chen WD. Two cases of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) New Chinese Medicine. 1984;15:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang RM, Chen WD, Lou ZP. A family of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Nerv Mental Dis. 1987;5:311–312. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun HT. Two cases of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2000;33:134. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang RM, Yu XE, Li K, Hou HX. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis and review (in Chinese) Chin Clin Neurosci. 2004;12:290–293. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bo L, Li YM, Liu FH. Care for one case of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Prac Nurs. 2005;21:54–55. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou XQ, Gua HZ, Shi XS, et al. Clinical, laboratory and neuroimaging characteristics of neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2012;45:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou LX, Guan HZ, Ni J, Wan XH, Chen L, Cui LY. Progressive involuntary movements in mouth tongue and limbs (in Chinese) Chin J Contemp Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;11:117–120. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu CY, Gao J, Yang YC, Cui LY, Wan XH, Ge CW. Chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Contemp Neurol Neurosurg. 2005;5:175–178. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei YP, Wan XH, Gao J, et al. Clinical and neuropathological study of three neuroacanthocytosis cases (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2005;38:712–713. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou H, Zhang XH, Sun YL. Report of two chorea-acanthocytosis cases (in Chinese) Chin J Neuroimmun Neurol. 2007;14:297–299. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu YH, Wang HJ, Dong S. Perioperative nursing of a patient with neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Nurs. 2010;45:413–415. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao XP, Tang LY, Chen F, Wei YZ, Yin WM, Zhang WW. One case report of neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Beijing Med J. 2013;35:407–408. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu HW. Experience of clinical nursing for one case of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Modern Journal of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine. 2013;22:668–669. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu EH, Xue XF, Wang XL, Xuang XQ, Jia JP. Clinical investigation of neuroacanthocytosis with the report of three cases (in Chinese) Chin J Intern Med. 2013;52:760–762. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xie SJ, Hu J, Chen KN, Shi SG. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) J Third Mil Med Univ. 2013;35:2045–2050. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang X. One case of neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin Gen Pract. 2009;12:2062. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang WX, Li JR, Yang SL, Zhang XZ, An YH, Chen HZ. Case report of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2003;36:331. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zheng BR, Han H, Qi ZZ, Wang DS. A case report of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Harbin Medical University Bulletin. 1989;23:126–127. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang JB, Gong LM, Dai JC, Han H. Two case-reports of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Harbin Medical University Bulletin. 1989;23:285. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang AY, Liang YQ. One case report of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Medic J Indust Enterpr. 1990;1:48. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qu SB, Liu LR, Sheng L, Li GL. One case of Chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Med Genet. 2003;20:176. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu SB, Liu LR, Sheng L, Li GL. Chorea-acanthocytosis presenting with elevated prolactin. Case report. IMJM. 2007;6:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang ZM, Cao YY. One case of neuroacanthocytosis, misdiagnosed as obsessive compulsive disorder (in Chinese) Chin J Psychiatry. 2005;38:26. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang AL, Zhao XY. Chorea-acanthocytosis: a clinical report of two cases (in Chinese) Chin J Neuromed. 2011;10:73–75. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma CM, Han YZ, Wang HL. One case report of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Prac Nerv Dis. 2012;15:96. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Man BL, Yuen YP, Yip SF, Ng SH. The first case report of McLeod syndrome in a Chinese patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2013-200205. pii:bcr2013200205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhao H, Mao SP. One case report of neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Stroke Nerv Dis. 2007;14:318–319. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Long X, Xiong N, Zhu Q, et al. The combination of SPECT-CT and functional MR imaging in the diagnosis of neuroacanthocytosis (abstract) Mov Disord. 2013;28(Suppl 1):715. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Z, Wang JL, Tang BS, et al. Using next-generation sequencing as a genetic diagnostic tool in rare autosomal recessive neurologic Mendelian disorders. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:2442.e11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao H, Wang C, Niu FN. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis and review (in Chinese) Chin J Diffic and Compl Cas. 2012;11:63–64. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dong GF, Bao LP, Jin N, Gong ZL, Lei ZL. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Prac Int Med. 1989;9:310. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo YC, Zhao B. Epilepsy-onset in chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Brain Neurol Dis J. 2005;13:449. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sa ru la B, Yuan J, Zhu RX. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Inner Mongolia Med J. 2007;39:1010. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jia RP, Zhao XY, Xu N, Bai XH, Zhang LJ. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis syndrome and literature review (in Chinese) Clinical Focus. 2012;27:1913–1914. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng GX. One case of neuroacanthocytosis and review (in Chinese) Chin J Diffic and Compl Cas. 2006;5:220. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu SP, Li DN, Wang SZ, et al. Familial neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2001;34:16–18. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luan HH, Liu YM, Zhang JY, Chen L, Li JH, Zhang XG. Clinical features of chorea-acanthocytosis complicated with chronic active hepatitis (report of one case) (in Chinese) J Clin Neurol. 2013;26:372–374. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shan PY, Meng YY, Yu XL, Liu SP, Li DN. Cognitive disorders and neuropsychiatric behaviors in chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Neurol. 2013;46:769–772. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen W, Wang WA, Liu ZG. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis and review (in Chinese) Chin J Prac Int Med. 2008;28:890–891. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang YP, Zhou Y. Case discussion of generalized dystonia in children (in Chinese) Chin Clin Neurosci. 2008;16:562–564. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang YP. Case discussion of late-onset cerebellar ataxia (in Chinese) Chin Clin Neurosci. 2010;18:223–224. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang QY, Wang YG, Jiang YP, et al. Ataxia-neuroacanthocytosis (3 cases report) (in Chinese) Chin Clin Neurosci. 2012;20:18–23. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ling L. Cerebellar ataxia in a case of neuroacanthocytosis (in Chinese) Journal of Sichuan of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2013;31:82–83. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cui AQ, Li YB, Liu XX, Chen YP, Li DR, Xu JL. Three cases in a family of hereditary chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Med Genet. 2004;5:421. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cui AQ, Li YB, Liu SP, Chen YP, Li DR, Xu JL. Hereditary chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Journal of Shanxi Medical University. 2005;36:93–95. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li P, Huang R, Song W, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the globus pallidus internal improves symptoms of chorea-acanthocytosis. Neurol Sci. 2012;33:269–274. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0741-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He SL, Zhang Y. One case of chorea-acanthocytosis (in Chinese) Chin J Postgrad Med. 1988;11:26. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lin FC, Wei LJ, Shih PY. Effect of levetiracetam on truncal tic in neuroacanthocytosis. Acta Neurol Taiwan. 2006;15:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung HH, Danek A, Walker RH. Neuroacanthocytosis syndromes. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:68. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-6-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dobson-Stone C, Velayos-Baeza A, Filippone LA, et al. Chorein detection for the diagnosis of chorea-acanthocytosis. Ann Neurol. 2004;56:299–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bostantjopoulou S, Katsarou Z, Kazis A, Vadikolia C. Neuroacanthocytosis presenting as parkinsonism. Mov Disord. 2000;15:1271–1273. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(200011)15:6<1271::aid-mds1037>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bader B, Walker RH, Vogel M, Prosiegel M, McIntosh J, Danek A. Tongue protrusion and feeding dystonia: a hallmark of chorea-acanthocytosis. Mov Disord. 2010;25:127–129. doi: 10.1002/mds.22863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bader B, Danek A, Walker RH. Chorea-acanthocytosis. In: Walker RH, editor. The differential diagnosis of chorea. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 122–148. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scheid R, Bader B, Ott DV, Merkenschlager A, Danek A. Development of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy in chorea-acanthocytosis. Neurology. 2009;73:1419–1422. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181bd80d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ong B, Devathasan G, Chong PN. Choreoacanthocytosis in a Chinese patient: a case report. Singapore Med J. 1989;30:506–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bayreuther C, Borg M, Ferrero-Vacher C, Chaussenot A, Lebrun C. Chorea-acanthocytosis without acanthocytes (in French) Rev Neurol (Paris) 2010;166:100–103. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Danek A, Rubio JP, Rampoldi L, et al. McLeod neuroacanthocytosis: genotype and phenotype. Ann Neurol. 2001;50:755–764. doi: 10.1002/ana.10035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]