Abstract

Background

Lower socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with cardiovascular disease. We sought to determine whether there is a higher prevalence of peripheral artery disease (PAD) in individuals with lower socioeconomic status.

Methods and Results

We analyzed data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2004. PAD was defined based on an ankle-brachial index (ABI) ≤ 0.90. Measures of SES included poverty-income ratio (PIR), a ratio of self-reported income relative to the poverty line, and attained education level. Of 6791 eligible participants, overall weighted prevalence of PAD was 5.8% (SE 0.3). PAD prevalence was significantly higher in individuals with low income and lower education. Individuals in the lowest of the 6 PIR categories had more than a 2-fold increased odds of PAD compared to those in the highest PIR category (OR 2.69, 95% CI 1.80–4.03, p<0.0001). This association remained significant even after multivariable adjustment (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.04–2.6, p=0.034). Lower attained education level also associated with higher PAD prevalence (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.96–4.0, p<0.0001) but was no longer significant after multivariable adjustment.

Conclusions

Low income and lower attained education level are associated with peripheral artery disease in US adults. These data suggest that individuals of lower socioeconomic status remain at high risk and highlight the need for education and advocacy efforts focused on these at-risk populations.

Keywords: Peripheral Artery Disease, Socioeconomic Status, Epidemiology

Despite marked improvements in cardiovascular care over the last several decades, substantial disparities persist in the management and outcomes of patients with cardiac and vascular diseases.1, 2 Socioeconomic status (SES), reflecting education, income, occupation, and social status, continues to be an important contributor to overall health. Low socioeconomic status has been linked with higher prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD), CHD mortality, and with higher rate of risk factors for CHD, such as diabetes, hypertension, smoking, and physical inactivity.3–5 Moreover, the substantial improvements in cardiovascular disease care have also not been experienced equally by all socioeconomic segments of the population.6, 7

While the association between SES and heart disease is well established,5, 8 there are few studies that have examined the relationship between socioeconomic status and peripheral artery disease (PAD). Existing studies of the association between SES and PAD have been inconsistent.9, 10 Furthermore, while it has been shown that racial disparities, gender, and cardiovascular risk factors affect the prevalence of PAD,11–14 the factors that account for the association of low SES with vascular disease are not well understood. We hypothesized that there would be a significantly higher prevalence of peripheral artery disease in individuals with lower socioeconomic status and sought to understand the factors that might account for an association between SES and PAD. We utilized nationally representative data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to explore the association of socioeconomic status and PAD in the US population.

Methods

NHANES is a series of surveys conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) to assess the heath and nutritional status of the civilian US population. By using a complex, stratified, multi-stage survey design with oversampling of traditionally under-represented individuals, NHANES is a nationally representative dataset. NHANES has been reviewed by and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the NCHS.

Definition of peripheral artery disease and ABI Methodology in NHANES

Ankle-brachial index (ABI) measurements were obtained as part of the NHANES lower extremity examination in adults ≥ 40 years during the survey years 1999–2004. According to NHANES protocol, blood pressure measurements were obtained with subjects in the supine position. Systolic blood pressure was measured in the right arm only and in the posterior tibial arteries at both ankles using an 8-MHz Doppler probe. We calculated the ABI for each leg by dividing the ankle pressure by the arm pressure. A diagnosis of PAD was assigned if either leg had an ABI ≤ 0.90. An ABI value > 1.40 was considered to reflect non-compressible vessels secondary to vascular calcification.

Definitions of socioeconomic variables

The poverty-income ratio (PIR) was used as a measure of household income. The PIR is a ratio of self-reported household income relative to a family’s poverty threshold based on family size and composition, year (allowing annual updates to account for inflation), and state of residence. Household income was self-reported as an absolute value. In the small number of individuals who chose not to provide exact income, income was reported as above or below $20,000. PIR could not be calculated for these respondents. A PIR value < 1.0 indicates family income below the poverty threshold. PIR was categorized as < 1.0, 1.0–1.99, 2.0–2.99, 3.0–3.99, 4.0–4.99, and ≥5.0 given that the PIR variable in NHANES was top coded at 5.0. PIR data was available for 6791 individuals in our sample population.

Participants provided their highest attained grade or level of education by self-report. Responses were categorized as less than 9th grade education, 9–11th grade, completed high school or equivalent, some college education, and college graduate or higher. We further categorized education as ‘less than high school,’ ‘high school or some college,’ and ‘college graduate or above.’ Education data was available on 7441 individuals in our sample population. Health insurance coverage was self-reported. Subject also reported whether coverage was private insurance, Medicare, or Medicaid.

Definitions of covariates

Age, gender, race/ethnicity, and smoking status were based on self-report as previously reported.15, 16 A diagnosis of hypertension was assigned if SBP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90, based on prior physician diagnosis, or if subjects reported taking a prescription medication for hypertension. Hyperlipidemia was considered present if subjects reported a physician diagnosis of elevated cholesterol or had a total cholesterol level ≥ 240 mg/dL (6.21 mmol/L). Subjects were considered to have diabetes if they reported a physician diagnosis of diabetes, were taking prescription medications for diabetes (either insulin or oral agents), or had non-fasting glucose values ≥ 200 mg/dL (11.1 mmol/L) or fasting glucose values ≥ 126 mg/dL (7 mmol/L). Diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) was based on an affirmative response to the question, “Has a doctor or other health professional ever told you that you had [coronary heart disease, angina (also called angina pectoris), heart attack (also called myocardial infarction), or stroke]?” The MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) study equation was used to estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), and eGFR <60 mL/min/m2 indicated chronic kidney disease (CKD).17

Medication use was self-reported, although interviewers examined all prescription medication containers when available to confirm medication use. We included statin therapy, aspirin and any antiplatelet therapy (including aspirin, clopidogrel, dipyridamole, ticlopidine, or combinations of these medications), angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) use, and beta-blocker use.

Statistical Methods

Analyses were performed with SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) using survey specific methods with use of appropriate sample weights, stratum, and primary sampling unit (PSU) variables to account for NHANES’ complex sample design. Descriptive statistics are reported as weighted mean and standard error (SE) for continuous variables or weighted proportion (or percentage) and SE for categorical variables. Categorical variables were compared by use of the χ2 test. Comparisons of mean values across groups and correlations between continuous variables were achieved by linear regression. The association of PAD and socioeconomic variables was estimated by logistic regression with data presented as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals. Multivariable logistic regression models were crafted to account for demographic variables (age, gender, race/ethnicity), atherosclerotic risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking status), existing cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and the inflammatory biomarker CRP. Additional analyses accounted for the other available measures of socioeconomic status (education for income analyses, and income for education analyses) and health insurance status. A two-sided p-value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

During the years 1999–2004, 7571 NHANES participants ≥ 40 years of age underwent ABI measurement. We excluded 113 subjects who had ABI ≥ 1.4 indicating vascular calcification artifact. After exclusion of 667 individuals without available socioeconomic data, the study population was comprised of 6791 NHANES participants. There were 586 cases of PAD for an overall weighted prevalence of 5.8% (SE 0.3).

Baseline characteristics and baseline socioeconomic variables are shown in Table 1. Participants with PAD were older and were more likely to be current or former smokers. Prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic kidney disease, and other cardiovascular disease was higher in subjects with PAD. BMI was not significantly different between the two groups. Subjects with PAD that were insured were more likely to have Medicare (reflecting the higher average age in this group) and Medicaid coverage. Fewer subjects with PAD had a college degree or higher.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics by PAD status (Total N = 6791)

| PAD Absent (N=6205) |

PAD Present (N=586) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 55.3 (0.2) | 68.0 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% male) | 48.6 (0.7) | 42.4 (2.6) | 0.04 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||

| Non-Hispanic white (%) | 77.9 (1.5) | 78.5 (2.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic black (%) | 8.7 (0.9) | 13.4 (2.0) | |

| Mexican American (%) | 4.6 (0.8) | 3.3 (1.0) | |

| Other (including multi-racial) (%) | 8.8 (1.1) | 4.8 (1.4) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 127.0 (0.4) | 139.3 (1.3) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73.8 (0.3) | 66 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | ||

| Never (%) | 46.9 (1.1) | 32.7 (2.6) | |

| Former (%) | 35.0 (0.9) | 44.9 (2.8) | |

| Active (%) | 18.0 (0.9) | 22.3 (1.8) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.3 (0.1) | 28.6 (0.3) | 0.4 |

| Diabetes (%) | 10.8 (0.4) | 24.5 (2.9) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 45.9 (1.2) | 73.2 (2.3) | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 46.7 (0.9) | 58.4 (2.3) | <0.0001 |

| History of CVD (%) | 10.6 (0.5) | 30.7 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease (% with GFR <60) | 10.1 (0.6) | 35.8 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Covered by health insurance (%)* | 88.9 (0.7) | 93.4 (1.5) | 0.02 |

| Private health insurance (%) | 80.7 (0.9) | 60.2 (2.6) | <0.0001 |

| Medicare (%) | 25.9 (0.9) | 65.8 (2.9) | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid (%) | 4.6 (0.5) | 8.1 (1.8) | 0.009 |

| Education status (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Less than high school | 18.8 (0.9) | 30.4 (2.5) | |

| High school or some college | 54.7 (1.1) | 53.2 (2.7) | |

| College graduate or above | 26.5 (1.3) | 16.4 (2.1) | |

| Poverty-income ratio (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| PIR < 1.0 | 9.7 (0.6) | 14.4 (1.9) | |

| PIR 1.0–1.99 | 17.7 (0.9) | 30.6 (2.2) | |

| PIR 2.0–2.99 | 14.7 (0.7) | 21.6 (2.6) | |

| PIR 3.0–3.99 | 14.8 (0.8) | 8.8 (1.7) | |

| PIR 4.0–4.99 | 13.2 (0.6) | 8.1 (1.6) | |

| PIR ≥ 5.0 | 29.9 (1.4) | 16.4 (2.8) |

CVD = Coronary heart disease, MI, angina, or stroke; GFR = glomerular filtration rate

Responses of individuals insurance programs may not add to 100% as individuals may ha1ve more than one type of insurance

We examined the baseline characteristics of patients who were excluded on the basis of missing socioeconomic data. Of the 667 patients excluded, there were 61 cases of PAD. There was no significant difference in the weighted prevalence of PAD in this group (7.3% (SE 1.2) compared to those included in the final analysis (5.8% (SE0.3), p=0.18). There were also no significant differences in the baseline characteristics of the individuals excluded from the analysis (data not shown).

Characteristics of all participants according to socioeconomic status (PIR category) are shown in Table 2. Individuals in the lowest income categories were more likely to be of non-White race/ethnicity, and had higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, including smoking, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. History of existing CVD was also more common in the lower PIR categories. Use of statin therapy, any lipid-lowering agent, aspirin or anti-platelet therapy, ACEI or ARB use, and beta-blocker use was lowest in the lower PIR category, though the trend across categories was not consistent (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics by poverty-income ratio (PIR) category

| Poverty-Income Ratio (and n per category) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 | 1.0–1.99 | 2.0–2.99 | 3.0–3.99 | 4.0–4.99 | ≥ 5.0 | p-value | |

| 1036 | 1751 | 1118 | 808 | 660 | 1418 | ||

| Baseline characteristics | |||||||

| Age (years) | 56.2 (0.6) | 60.6 (0.5) | 58.3 (0.6) | 54.6 (0.7) | 53.7 (0.5) | 53.6 (0.4) | <0.0001 |

| Gender (% female) | 57 (1.9) | 58.1 (1.1) | 52.7 (1.6) | 52.4 (1.7) | 49.7 (1.4) | 49.7 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Non-Hispanic white (%) | 53.1 (4.1) | 68.9 (3.0) | 74.1 (2.3) | 83.4 (1.7) | 84.1 (2.2) | 88.7 (1.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic black (%) | 17.7 (2.9) | 12.2 (1.5) | 11.1 (1.4) | 6.7 (0.9) | 5.4 (0.9) | 5.6 (0.7) | |

| Mexican American (%) | 10.2 (2.5) | 7.6 (1.4) | 5.4 (1.1) | 3.5 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.2) | |

| Other (including multi-racial) (%) | 18.9 (3.9) | 11.2 (1.9) | 9.4 (1.7) | 6.5 (1.2) | 7.9 (1.7) | 4.2 (0.7) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130.2 (1.0) | 132.0 (0.8) | 129.5 (0.9) | 126.3 (0.8) | 126.3 (0.8) | 124.6 (0.6) | <0.0001 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 73.8 (0.6) | 71.6 (0.5) | 72.1 (0.6) | 73.7 (0.5) | 75.0 (0.5) | 74.1 (0.4) | 0.0007 |

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Never (%) | 42.6 (1.9) | 43.7 (1.4) | 44.3 (1.9) | 42.8 (2.2) | 45.9 (2.1) | 51.5 (2.0) | |

| Former (%) | 25.4 (1.2) | 34.8 (1.1) | 37.5 (1.7) | 38.3 (2.5) | 37.5 (2.1) | 36.4 (1.9) | |

| Active (%) | 31.9 (2.1) | 21.3 (1.2) | 18.2 (1.6) | 18.9 (2.3) | 16.6 (2.0) | 12.1 (1.4) | |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 28.7 (0.3) | 28.3 (0.2) | 28.7 (0.2) | 28.1 (0.2) | 28.7 (0.3) | 27.9 (0.2) | 0.002 |

| Diabetes (%) | 16.7 (1.4) | 17.2 (1.3) | 13.3 (1.5) | 10.2 (1.0) | 9.6 (1.2) | 7.1 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (%) | 52.4 (2.1) | 57.7 (1.6) | 53.1 (2.2) | 42.4 (2.6) | 46.4 (2.3) | 39.3 (1.8) | <0.0001 |

| Hyperlipidemia (%) | 47.2 (2.2) | 49.0 (1.7) | 47.2 (2.0) | 48.3 (1.8) | 46.1 (2.3) | 46.6 (1.1) | 0.8 |

| History of CVD (%) | 15.5 (1.2) | 19.0 (1.0) | 12.0 (1.3) | 8.9 (1.4) | 9.5 (1.4) | 8.1 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| History of CHF (%) | 5.6 (1.1) | 5.2 (0.6) | 3.3 (0.6) | 2.2 (0.6) | 1.4 (0.4) | 1.7 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| CKD (% with GFR <60) | 13.1 (1.5) | 18.2 (1.2) | 14.6 (1.4) | 9.4 (1.2) | 8.6 (1.1) | 7.5 (0.9) | <0.0001 |

| Education | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Less than high school (%) | 47.5 (2.6) | 38.9 (2.3) | 20.4 (1.7) | 12.5 (1.4) | 11.0 (1.8) | 4.2 (0.5) | |

| High school or some college (%) | 45.9 (2.9) | 53.3 (2.2) | 64.5 (1.7) | 63.1 (2.3) | 57.6 (2.6) | 47.8 (1.7) | |

| College graduate or above (%) | 6.6 (1.4) | 7.7 (0.9) | 15.0 (1.6) | 24.4 (2.0) | 31.3 (2.3) | 48.0 (1.8) | |

| Health insurance (%) | 71.6 (1.7) | 77.1 (1.4) | 89.1 (1.3) | 92.9 (1.3) | 96.0 (1.1) | 97.8 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Private insurance (%) | 36.5 (3.8) | 58.6 (2.0) | 77.2 (1.7) | 88.9 (1.3) | 88.5 (1.7) | 93.3 (0.7) | <0.0001 |

| Medicare (%) | 41.9 (3.1) | 56.7 (2.6) | 41.7 (2.2) | 22.9 (1.6) | 18.1 (1.4) | 11.8 (1.0) | <0.0001 |

| Medicaid (%) | 34.1 (3.6) | 10.2 (1.2) | 1.9 (0.5) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.3 (0.2) | 0.06 (0.04) | <0.0001 |

| Medication use | |||||||

| Statin use (%) | 10.9 (1.3) | 17.6 (1.3) | 17.2 (1.3) | 13.4 (1.2) | 13.4 (1.5) | 15.2 (1.5) | 0.01 |

| Any lipid-lowering agents (%) | 12.2 (1.3) | 19.1 (1.3) | 19.7 (1.4) | 14.5 (1.2) | 15.5 (1.6) | 16.8 (1.6) | 0.007 |

| Aspirin use (%) | 16.4 (1.5) | 22.7 (1.9) | 23.6 (1.6) | 19.7 (2.1) | 19.8 (1.8) | 18.9 (1.4) | 0.04 |

| Any anti-platelet therapy (%) | 17.2 (1.4) | 23.8 (1.9) | 24.2 (1.6) | 20.1 (2.2) | 20.2 (1.8) | 19.1 (1.4) | 0.03 |

| ACEI/ARB use (%) | 12.8 (1.4) | 18.1 (1.3) | 16.0 (1.3) | 11.5 (1.3) | 12.9 (1.3) | 12.0 (1.2) | 0.0002 |

| Beta-blocker use (%) | 10.0 (1.4) | 14.1 (0.9) | 13.2 (1.3) | 9.6 (1.0) | 10.2 (1.2) | 11.9 (1.0) | 0.03 |

PAD and income

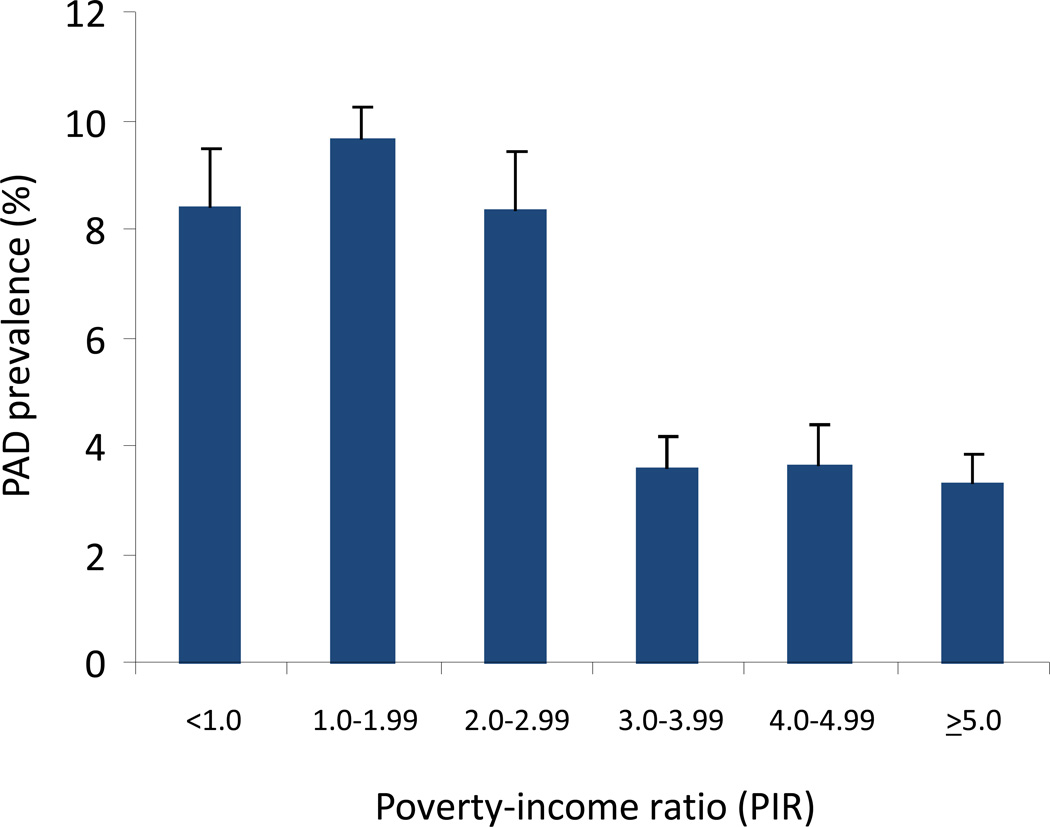

PAD prevalence was significantly higher in individuals in lower income categories (Figure 1). Accordingly, when compared to individuals in the highest PIR category (≥5), the odds of PAD was significantly higher for individuals with PIR < 1.0 (OR 2.69, 95% CI 1.8–4.0, p<0.0001), PIR 1.0–1.99 (OR 3.14, 95% CI 2.2–4.4, p<0.0001), and PIR 2.0–2.99 (OR 2.67, 95% CI 1.7–4.3, p<0.0001) (Table 3). The odds of PAD were not significantly different for those in higher PIR categories compared to the highest income category (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.6–1.9 for PIR 3.0–3.99 and OR 1.1, 95% CI 0.7–1.9 for PIR 4.0–4.99). The association remained statistically significant for the lowest three PIR categories even after adjustment for age, gender, and race/ethnicity (Table 3). After additional multivariable adjustment including atherosclerotic risk factors, existing CVD, CKD, CRP, education and insurance status, the odds of PAD remains significantly higher in the lowest PIR category (OR 1.64, 95%CI 1.04–2.6, p=0.034).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of PAD by poverty-income ratio (PIR) category. PIR is a ratio of self-reported household income relative to a family’s poverty threshold A PIR value < 1.0 indicates family income below the poverty threshold. PIR was categorized as < 1.0, 1.0–1.99, 2.0–2.99, 3.0–3.99, 4.0–4.99, and ≥5.0.

Table 3.

Association of Income (Poverty-income ratio) and PAD

| Poverty-income ratio (PIR) category | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.0 | 1.0–1.99 | 2.0–2.99 | 3.0–3.99 | 4.0–4.99 | ≥ 5.0 | |

| Unadjusted | 2.69 (1.8–4.0) | 3.14 (2.2–4.4) | 2.67 (1.7–4.3) | 1.08 (0.6–1.9) | 1.1 (0.7–1.9) | ref |

| Model 1 (unadjusted model + age, gender, race/ethnicity) | 2.11 (1.4–3.3) | 1.70 (1.2–2.4) | 1.73 (1.02–2.9) | 0.93 (0.5–1.6) | 1.03 (0.63–1.7) | ref |

| Model 2 (model 1 + DM, HTN, hyperlipidemia, smoking) | 1.69 (1.1–2.6) | 1.40 (0.98–2.0) | 1.50 (0.87–2.6) | 0.83 (0.48–1.5) | 0.97 (0.58–1.6) | ref |

| Model 3 (model 2 + CVD, CKD, CHF, and CRP) | 1.67 (1.1– 2.5) | 1.29 (0.92–1.8) | 1.48 (0.86–2.5) | 0.82 (0.47–1.5) | 0.97 (0.58–1.6) | ref |

| Model 4 (model 3 + income and insurance status) | 1.64 (1.04–2.6) | 1.26 (0.86–1.9) | 1.46 (0.83–2.6) | 0.82 (0.45–1.5) | 0.97 (0.57–1.6) | ref |

Based on the prevalence data suggesting a threshold of increased PAD prevalence in the lower three PIR categories <1.0, 1.0–1.99, and 2.0–2.99 (Figure 1), we dichotomized PIR in two categories (< 3.0 or ≥ 3.0). Individuals with PIR < 3.0 had a nearly 3-fold increased odds of PAD compared to those in the higher PIR categories (OR 2.75, 95% CI 2.2–3.5, p<0.0001). This relationship remained statistically significant even after multivariable adjustment for demographics (OR 1.81, 95% CI 1.4–2.4, p<0.0001), as well as atherosclerotic risk factors, CVD, CKD, CRP, education, and insurance status with individuals of lower income having a 50% increased odds of PAD compared to those in higher income categories (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.13–1.98, p=0.0045). There was no significant difference in the findings even after adjusting for differences in use of cardiovascular risk modifying medications, such as anti-platelet therapy, statins, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors or ARBs.

PAD and education level

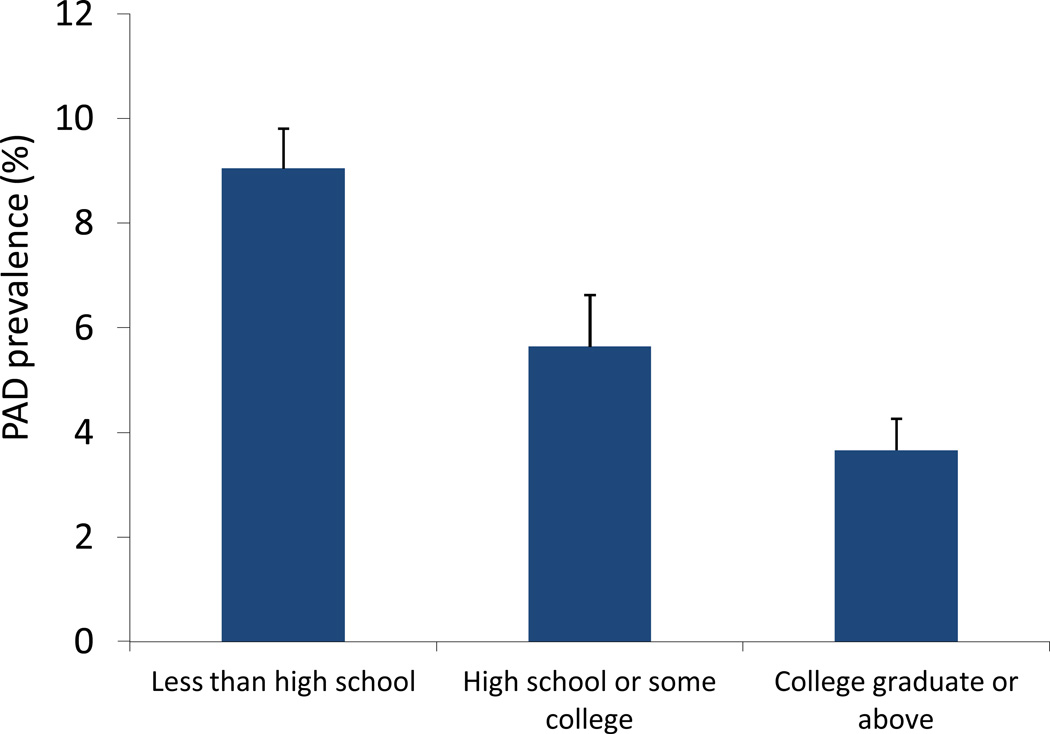

Compared to individuals without PAD (Table 1), participants with PAD had lower education levels with more PAD subjects having less than high school level of education (30.4% ± 2.5% vs. 18.8% ± 0.9%) and fewer having completed college (16.4% ± 2.1% vs. 26.5% ± 1.3%). When considering the prevalence of PAD according to education level, there was significantly greater PAD prevalence in individuals with lower levels of achieved education (Figure 2). The highest prevalence of PAD was noted in individuals with less than high school education (9.0% ± 0.7%) and the lowest prevalence was in those with a college education or greater (3.7% ± 0.5%), resulting in an unadjusted odds of PAD was 2.8 (95% CI 1.96–4.0, p<0.0001) among those with less than high school education level and 1.69 (95% CI 1.2–2.4, p<0.0001) among those with high school education or some college compared to those with a college education or greater (Table 4). These findings remained significant after adjustment for demographics, but were no longer significant in a fully adjusted model (OR was 1.02 (95% CI 0.7–1.5, p=0.9) for those with less than high school education after full multivariable adjustment (Table 4). Findings were similar for those with high school education or some college (OR 1.005, 95% CI 0.7–1.4, p=0.9) compared to the highest level of education. These findings remained unchanged after additionally accounting for differences in medication use (including anti-platelet therapy, statins, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors or ARBs).

Figure 2.

Prevalence of PAD according to highest attained education level.

Table 4.

Association of Attained Education Level and PAD

| Less than HS | HS/some college | College or greater |

p-trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |||

| Unadjusted | 2.8 (1.96–4.02) | <0.0001 | 1.69 (1.2–2.36) | <0.0001 | ref | <0.0001 |

| Model 1 (unadjusted model + age, gender, race/ethnicity) | 1.87 (1.26–2.78) | 0.0019 | 1.43 (1.02–2.02) | 0.038 | ref | 0.0017 |

| Model 2 (model 1 + DM, HTN, hyperlipidemia, smoking) | 1.44 (0.98–2.1) | 0.06 | 1.19 (0.84–1.68) | 0.3 | ref | 0.055 |

| Model 3 (model 2 + CVD, CKD, CHF, and CRP) | 1.38 (0.93–2.1) | 0.11 | 1.18 (0.82–1.7) | 0.4 | ref | 0.1 |

| Model 4 (model 3 + income and insurance status) | 1.04 (0.7–1.6) | 0.9 | 1.005 (0.7–1.4) | 0.9 | ref | 0.8 |

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of adults in the United States, we observed a strong relationship between indicators of lower socioeconomic status, such as income or education level, and higher prevalence of PAD. The relationship between PAD and low income persisted even after multivariable adjustment, including adjustment for other socioeconomic variables, such as education and insurance status. As might be expected, however, the association was attenuated by demographic factors and disparities in the prevalence of recognized cardiovascular risk factors. These data demonstrate that income has a significant impact on the prevalence of vascular disease but that some of this effect may be due to factors not accounted for in traditional demographics and cardiovascular risk factors. In contrast, the association between education and PAD was largely accounted for by demographics and by the prevalence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors.

That socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular disease are linked is well established.5, 8 However, the relationship of socioeconomic factors to peripheral vascular disease in particular has been less rigorously studied and prior studies were inconsistent.11, 18 Data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) did not demonstrate an association between an individual’s cumulative SES across the life course with prevalence of PAD.9 In contrast, a prospective cohort study from Germany demonstrated greater prevalence of PAD and lower ankle-brachial index measurements with lower education and income levels; however, the findings were no longer significant after multivariable adjustment.10 Prior studies have also shown that lower SES in patients with PAD may also be linked to worse vascular outcomes.9, 12, 19 One study showed a 65% greater rate of PAD-related amputations in individuals of lower socioeconomic status.12 Our data are unique and novel in that they provide nationally representative and generalizable data from the United States using NHANES. These data also for the first time suggest a strong and persistent association between lower socioeconomic status, particularly income, and prevalence of PAD.

The present study also helps broaden the understanding of the factors that may contribute to the association between PAD and SES. While demographic factors, including race/ethnicity, and traditional atherosclerotic risk factors, such as diabetes, hypertension, and smoking, contribute, they only partially account for these findings. The impact of racial disparities on the association between PAD and socioeconomic status is underscored by prior studies showing that black patients with PAD are more likely to undergo amputation, and less likely to undergo revascularization or wound debridement prior to amputation.20 However, our data also show that the association between income and PAD remains significant even after adjusting for race and ethnicity, traditional cardiovascular risk factors, co-morbid cardiac conditions, and even other socioeconomic variables, including education and health insurance status. In addition, despite recent work from Subherwal and colleagues demonstrating disparities in the use of cardiovascular medications among patients with PAD, we did not find that medication use affected the relationship between SES and prevalence of PAD.21

Inflammatory markers, strongly linked to vascular disease,22–24 are higher in individuals of lower income and education, suggesting they might serve as mediators of the link between SES and PAD.25, 26 For example, in Women’s Health Study, the association of low SES and incident cardiovascular events was explained partially by novel cardiovascular risk factors including C-reactive protein, iCAM-1 (intercellular adhesion molecule-1), and fibrinogen.27 In the present dataset, only CRP was available for inclusion in multivariable model, but we found that the relationship between income and PAD remained significant even after addition of this inflammatory marker into the model.

Several other unmeasured factors may serve as mediators of the SES and PAD association. Chronic psychosocial stress is known to have a major impact on cardiovascular disease.28, 29 Impaired lower extremity function can have an adverse impact on health-related quality of life and perceived stress may further impair quality of life in patients with PAD.30, 31 However, whether stress may have a causal effect on PAD prevalence remains unclear.

It is important to note that education and income are only two of many potential measures of socioeconomic status, and while both are measures of socioeconomic status, they may have distinct effects on overall health. Our dataset does not allow assessment of other measures of SES, including total wealth (which may be a better measure of an individual’s ability to withstand financial or social stressors), familial and friend networks, material goods, and power and prestige. Also difficult to capture in SES is the reflection of overall access to resources and opportunities that may impact health outcomes.

The disparities in PAD prevalence highlighted here indicate that we need dedicated approaches to PAD awareness efforts, research endeavors, and treatment strategies that focus on those individuals of low socioeconomic strata who may be most likely to be affected by PAD. A telephone survey to assess PAD awareness showed that knowledge gaps around PAD were more notable in less educated and lower income respondents.32 Accordingly, PAD awareness efforts need to be targeted to subpopulations of lower socioeconomic status that have the greatest gaps in awareness and who at the same time are at higher risk of developing PAD. Similarly, in the evaluation and implementation of new therapies or treatment strategies, we need not only consider that differences in outcomes may arise from socioeconomic differences, but also that we need to improve strategies to allow beneficial treatments to reach all segments of the population equally.

The limitations of these data are important to acknowledge. First, there are inherent and recognized limitations in the income and education variables used to reflect SES. Income, while theoretically easy to measure, can be limited by a respondent’s lack of willingness to reveal it. However, studies examining the reliability of self-reported income suggest that when compared to ‘true’ wage and salary information (e.g., tax records), there is generally low bias and error.33 In some cases, and perhaps more so in lower socioeconomic strata, income can vary over a short period of time and can vary over one’s lifetime. In addition, the impact of income differs based on family size. We have accounted for this limitation by using the poverty-income ratio instead of raw income. Income is also not a surrogate for wealth, and wealth, which includes not only income but also other existing resources such as real estate and stock ownership, may be a better measure of an individual’s ability to withstand financial stress. Though an excellent measure of SES, wealth is very difficult to measure and not available in our dataset. There are additional limitations to the measurement of ankle-brachial index and cardiovascular risk factors that have previously been addressed.15, 34 In particular, the ABI calculation is limited by the fact that in NHANES brachial artery blood pressure was measured in only one arm and ankle pressure was measured only at the posterior tibial artery, raising the potential for misclassification. Furthermore, because these data are cross-sectional, we cannot determine causality. Prospective studies with incident PAD events would be required to clarify this relationship further.

Acknowledging these limitations, the fact that low SES is strongly associated with PAD should lead us to better consider our advocacy and education efforts around peripheral artery disease. Without question, subpopulations exist here in the United States that remain at substantially higher risk of developing a disease with substantial morbidity and mortality. PAD remains highly prevalent with prior data estimating more than 7 million patients in the United States alone. We need improved public awareness efforts that are targeted towards these populations within lower socioeconomic strata that remain at risk. Though we cannot know whether improving socioeconomic status will reduce prevalence of PAD or PAD outcomes, wider outreach to populations at risk can improve awareness and hopefully lower the adverse impact of PAD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Dr. Pande has received support from a Research Career Development Award (K12 HL083786) from the National, Heart, Lung Blood Institute and is the recipient of a Scientist Development Grant (10SDG4200060) from the American Heart Association. Dr. Creager is the Simon C. Fireman Scholar in Cardiovascular Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Footnotes

Disclosures

No relevant disclosures to report.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2013 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of Disparities in Cardiovascular Health in the United States. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alter DA, Franklin B, Ko DT, Austin PC, Lee DS, Oh PI, Stukel TA, Tu JV. Socioeconomic Status, Functional Recovery, and Long-Term Mortality among Patients Surviving Acute Myocardial Infarction. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luepker RV, Rosamond WD, Murphy R, Sprafka JM, Folsom AR, McGovern PG, Blackburn H. Socioeconomic Status and Coronary Heart Disease Risk Factor Trends. The Minnesota Heart Survey. Circulation. 1993;88:2172–2179. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaplan GA, Keil JE. Socioeconomic Factors and Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of the Literature. Circulation. 1993;88:1973–1998. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.4.1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholes S, Bajekal M, Love H, Hawkins N, Raine R, O'Flaherty M, Capewell S. Persistent Socioeconomic Inequalities in Cardiovascular Risk Factors in England over 1994–2008: A Time-Trend Analysis of Repeated Cross-Sectional Data. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:129. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Oeffelen AA, Agyemang C, Bots ML, Stronks K, Koopman C, van Rossem L, Vaartjes I. The Relation between Socioeconomic Status and Short-Term Mortality after Acute Myocardial Infarction Persists in the Elderly: Results from a Nationwide Study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012;27:605–613. doi: 10.1007/s10654-012-9700-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlamangla AS, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Seeman TE. Socioeconomic and Ethnic Disparities in Cardiovascular Risk in the United States, 2001–2006. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:617–628. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carson AP, Rose KM, Catellier DJ, Kaufman JS, Wyatt SB, Diez-Roux AV, Heiss G. Cumulative Socioeconomic Status across the Life Course and Subclinical Atherosclerosis. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kroger K, Dragano N, Stang A, Moebus S, Mohlenkamp S, Mann K, Siegrist J, Jockel KH, Erbel R. An Unequal Social Distribution of Peripheral Arterial Disease and the Possible Explanations: Results from a Population-Based Study. Vascular medicine. 2009;14:289–296. doi: 10.1177/1358863X09102294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rooks RN, Simonsick EM, Miles T, Newman A, Kritchevsky SB, Schulz R, Harris T. The Association of Race and Socioeconomic Status with Cardiovascular Disease Indicators among Older Adults in the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. The journals of gerontology. Series B, Psychological sciences and social sciences. 2002;57:S247–S256. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.s247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferguson HJ, Nightingale P, Pathak R, Jayatunga AP. The Influence of Socio-Economic Deprivation on Rates of Major Lower Limb Amputation Secondary to Peripheral Arterial Disease. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2010;40:76–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fowkes FG, Housley E, Cawood EH, Macintyre CC, Ruckley CV, Prescott RJ. Edinburgh Artery Study: Prevalence of Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Peripheral Arterial Disease in the General Population. International journal of epidemiology. 1991;20:384–392. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meadows TA, Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Creager MA, Califf RM, Ohman EM, Cannon CP, Eagle KA, Alberts MJ, Goto S, Smith SC, Jr, Wilson PW, Watson KE, Steg PG. Ethnic Differences in the Prevalence and Treatment of Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Us Outpatients with Peripheral Arterial Disease: Insights from the Reduction of Atherothrombosis for Continued Health (REACH) Registry. Am Heart J. 2009;158:1038–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Association of Insulin Resistance and Inflammation with Peripheral Arterial Disease: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2004. Circulation. 2008;118:33–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.721878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perlstein TS, Pande RL, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Serum Total Bilirubin Level and Prevalent Lower-Extremity Peripheral Arterial Disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999 to 2004. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:166–172. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.153262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, Kusek JW, Van Lente F. Using Standardized Serum Creatinine Values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Equation for Estimating Glomerular Filtration Rate. Annals of internal medicine. 2006;145:247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fowkes FG, Housley E, Cawood EH, Macintyre CC, Ruckley CV, Prescott RJ. Edinburgh Artery Study: Prevalence of Asymptomatic and Symptomatic Peripheral Arterial Disease in the General Population. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20:384–392. doi: 10.1093/ije/20.2.384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen LL, Henry AJ. Disparities in Vascular Surgery: Is It Biology or Environment? J Vasc Surg. 2010;51:36S–41S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holman KH, Henke PK, Dimick JB, Birkmeyer JD. Racial Disparities in the Use of Revascularization before Leg Amputation in Medicare Patients. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.02.035. 426 e421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subherwal S, Patel MR, Tang F, Smolderen KG, Jones WS, Tsai TT, Ting HH, Bhatt DL, Spertus JA, Chan PS. Socioeconomic Disparities in the Use of Cardioprotective Medications among Patients with Peripheral Artery Disease: An Analysis of the American College of Cardiology's Ncdr Pinnacle Registry. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;62:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pradhan AD, Shrivastava S, Cook NR, Rifai N, Creager MA, Ridker PM. Symptomatic Peripheral Arterial Disease in Women: Nontraditional Biomarkers of Elevated Risk. Circulation. 2008;117:823–831. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.719369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ridker PM, Stampfer MJ, Rifai N. Novel Risk Factors for Systemic Atherosclerosis: A Comparison of C-Reactive Protein, Fibrinogen, Homocysteine, Lipoprotein(a), and Standard Cholesterol Screening as Predictors of Peripheral Arterial Disease. Jama. 2001;285:2481–2485. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pradhan AD, Rifai N, Ridker PM. Soluble Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1, Soluble Vascular Adhesion Molecule-1, and the Development of Symptomatic Peripheral Arterial Disease in Men. Circulation. 2002;106:820–825. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000025636.03561.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muennig P, Sohler N, Mahato B. Socioeconomic Status as an Independent Predictor of Physiological Biomarkers of Cardiovascular Disease: Evidence from Nhanes. Prev Med. 2007;45:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gruenewald TL, Cohen S, Matthews KA, Tracy R, Seeman TE. Association of Socioeconomic Status with Inflammation Markers in Black and White Men and Women in the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (Cardia) Study. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert MA, Glynn RJ, Buring J, Ridker PM. Impact of Traditional and Novel Risk Factors on the Relationship between Socioeconomic Status and Incident Cardiovascular Events. Circulation. 2006;114:2619–2626. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.660043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dimsdale JE. Psychological Stress and Cardiovascular Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1237–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steptoe A, Feldman PJ, Kunz S, Owen N, Willemsen G, Marmot M. Stress Responsivity and Socioeconomic Status: A Mechanism for Increased Cardiovascular Disease Risk? Eur Heart J. 2002;23:1757–1763. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2001.3233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aquarius AE, De Vries J, Henegouwen DP, Hamming JF. Clinical Indicators and Psychosocial Aspects in Peripheral Arterial Disease. Arch Surg. 2006;141:161–166. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.2.161. discussion 166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aquarius AE, Denollet J, Hamming JF, De Vries J. Age-Related Differences in Invasive Treatment of Peripheral Arterial Disease: Disease Severity Versus Social Support as Determinants. J Psychosom Res. 2006;61:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovell M, Harris K, Forbes T, Twillman G, Abramson B, Criqui MH, Schroeder P, Mohler ER, 3rd, Hirsch AT. Peripheral Arterial Disease: Lack of Awareness in Canada. Can J Cardiol. 2009;25:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(09)70021-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. [October 21, 2013]; http://www.census.gov.edgekey.net/srd/papers/pdf/sm97-05.pdf.

- 34.Pande RL, Perlstein TS, Beckman JA, Creager MA. Secondary Prevention and Mortality in Peripheral Artery Disease: National Health and Nutrition Examination Study, 1999 to 2004. Circulation. 2011;124:17–23. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.