Abstract

Background: A Prostate Cancer Unit is a place where men can be cared for by specialists in prostate cancer (PC), working together within a multi-disciplinary team (MDT). The MDT approach guarantees a higher probability for the PC patient to receive adequate information on the disease and on all possible therapeutic strategies, balancing advantages and related side effects. Objecive: To analyze the role of a MDT in PC management and to compare some results in terms of characteristics and distribution of PC cases, obtained by a MDT, with those reported by a monodisciplinary urological unit. Outcome measurements and results: A high percentage of cases (47.6%) referred to our MDT were in the low risk group. In the Prostate cancer Unit the indications for primary therapies were more equally distributed between surgery (51.5%) and radiotherapy (45.4%). Conclusions: The future of PC patients relies in a successful multidisciplinary collaboration between experienced physicians which can led to important advantages in all the phases of PC.

Keywords: Prostate neoplasm, multidisciplinary team, Prostate Unit

Bases for the development of Prostate Cancer Units

Prostate cancer (PC) is established as one of the most important medical problems facing the male population. PC is the most common solid neoplasm (214 cases per 1000 men) and the second most common cause of cancer death in men [1].

Its management involves several complex issues for both clinicians and patients. An early diagnosis is necessary to implement well-balanced therapeutic options and the correct evaluation can reduce the risk of overtreatment with its consequential adverse effects [2]. The optimal management for localized PC is controversial, with options including active surveillance, surgery, radiotherapy and focal therapies. The management of the progressive disease after primary treatments and that of the advanced PC requires a correct diagnostic evaluation and a therapeutic choice among radiotherapy, focal therapies, hormone therapies, chemotherapies or other novel target treatments [3].

Efficient organization of the national healthcare system can be a tool to help improve patient outcomes.

The natural history of PC from asymptomatic organ-confined disease to locally advanced, metastatic and hormone-refractory disease, describes the complexity of the biology of this tumor and justifies the need for a fluid collaboration between expert physicians.

Breast and Prostate cancer, respectively, are the most common cancers in women and in men, and different similarities have been underlined. The paradigm of the patient consulting a multidisciplinary medical team has been an established standard approach in treating breast cancer [4]. Such multidisciplinary approach can offer the same optional care for men with PC as it does for woman with breast cancer.

In other disease sites, multidisciplinary cancer clinics have been associated with decreased time from diagnosis to initiation of treatment, shorter time to completion of necessary pretreatment consultations, and fewer patient visits to clinicians’ offices before initiation of care [5]. Multidisciplinary physician discussions have been shown to be associated with improved adherence to guidelines supported by the literature [6]. In a multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinic, newly diagnosed patients can simultaneously meet with urologic, radiation, and medical oncologists specializing in prostate cancer. Such a model of cancer care affords patients the opportunity to learn about all management options simultaneously and to discuss the recommendations of their treating physicians in an open and interactive fashion, allowing for shared decision making and a potential reduction in physician bias. Although it is important to note that such benefits have been demonstrated in oncological disease sites other than PC, in the last ten years several experiences on multidisciplinary management of PC has been published showing several advantages in the management of PC. Valdagni et al [7], recently reported their 6-years experience of a MDT prostate cancer clinic: interestingly, they reported that most of the patients with PC were staged in the low-risk group and that numbers increase significantly from 40% in 2006 to 61% in 2009. Moreover, they reported an high percentage (about 80%) of patients managed with active surveillance. This data is very interesting and It underlined that active surveillance, as reasonable approach today in patients with low grade disease, is more often a therapeutic choice in a MDT were the methods are often standardized. Similar results were reported by other authors from other countries [8]. Aizer et co-authors reported their experience on 701 men with low-risk prostate cancer managed at three tertiary care centers in Boston [9]. In this study active surveillance in patients seen at a multidisciplinary clinic were double that of patients seen by individual practitioners (43% v 22%), whereas the proportion of men treated with prostatectomy or radiation decreased by approximately 30% (P<0.001). Interestingly, the number of physicians and specialties seen was significantly associated with the choice of active surveillance on univariate, but not multivariate analysis, suggesting that the multidisciplinary clinic itself, and not merely the number or type of physicians seen, is important to the shared decision making process for selection of active surveillance and more generally to choose the best treatment for each individual patient. This aspect of MDT is very important because previous studies examining patterns of care in patients with low-risk prostate cancer have consistently shown that specialists prefer the modality of treatment that they themselves deliver [10-12].

Given that a multidisciplinary management can bring several advantages in the management of patients with PC, another important aspect is how the patient perceives a multidisciplinary management and which grade of satisfaction patients can have. Magnani T et al reported on a 6-years attendance of multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinics [7]. To evaluate overall patient satisfaction, the patients were periodically asked to complete a 10-item satisfaction questionnaire, covering several aspect sof the patient’s management, including Physician Referral Service, waiting time, information given on health and medical care. Patient satisfaction ratings were high: the investigators used a 7-point scale (in which a score of 1 designates “very poor quality”, whereas a score of 7 indicates “very high quality”). Scores between 5 and 7 were achieved for all measured domains, including observance of privacy, care provided by technical/nursing staff, care provided by the clinical staff, information on health and medical care provided.

The management of prostate cancer is complicated by the multitude of management options, the lack of proven superiority of one modality of management, and the presence of physician bias. The available data suggest that implementation of multidisciplinary models of care for patients with cancer, when feasible, may be associated with high patient satisfaction rates and may alter practice patterns in ways that minimize physician bias [9].

How to organize a Prostate Cancer Unit

Given that a multidisciplinary approach can bring many advantages in the management of patients with PC, an important aspect is how to organize a Prostate Cancer Unit.

Quality cancer care is complex and depends upon careful coordination between multiple treatments and providers and upon technical information exchange and regular communication flow between all those involved in treatment (including patients, specialist physicians, other specialty disciplines, primary care physicians, and support services) [13-15]. As suggested by Valdagni et al, a Prostate Cancer Unit is a place where men can be cared for by specialists in PC working together within a multi-professional team [16].

From October 2010 our hospital accepted the institution of a Prostate Cancer Unit. Our Prostate Unit was established in large size hospital, covering a population of more than 300,000 people.

The main aim of the Unit was to provide a continuum of care for patients through early diagnosis, treatment planning in all stages of the disease, follow-up, prevention and management of complications related to PC. Patients that can be followed by the Prostate Cancer Unit include cases in which the diagnosis is as yet un-established but whose could benefit for an early diagnosis program; cases in which the diagnosis of PC is confirmed and whose can be considered for treatment planning; cases following primary treatment for discussion of further care; cases in follow-up after or during treatment.

Following indications from previous experiences [16], we accepted some basic requirements for our Prostate Cancer Unit:

1. The Unit is represented by a core team whose members have a specialist training in prostate disorders, spend a relevant amount of their time working with PC, undertake continuing professional education, have a high level scientific production on PC experimental and clinical research.

2. The core team include: two Coordinators (one referred for the diagnostic and one for the clinical therapeutic management of PC) from any specialist of the team; urologists (spending 50% or more of their working time in prostate disease, managing at least 100 PC cases per year, carrying out at least 25 radical prostatectomies per year and at least one prostate clinic per week); an urologist/radiologist dedicated in prostate biopsies (spending more than 70% of his working time in prostate biopsies, performing more than 400 prostate biopsies per year), an uro-pathologist (spending 30% or more of his working time in prostate disease, analyzing at least 250 sets of prostate biopsies per year); radiation oncologists (spending 50% or more of their working time in prostate disease, carrying out radiotherapy on at least 25 PC per year); medical oncologists (spending 30% or more of their working time in prostate disease, managing at least 50 PC cases per year); two radiologists (with main experience in all aspects of prostate imaging, one using multiparametric magnetic resonance and ultrasonography and one as expert in nuclear medicine, spending 50% or more of his working time in prostate disease). Additional professional services also include a sexuologist/andrologist, psychologist, palliative care specialist, a clinical trials coordinator.

3. The Prostate Cancer Unit must be of sufficient size (number of specialists) to have more than 100 new diagnosed cases of PC coming under its care each year.

4. Research and scientific production is an important part of the activity of the Prostate Cancer Unit, such as also participation into clinical trials for the management of PC.

5. All specialists of the Prostate Cancer Unit core team organize and participate to multidisciplinary meetings every 10 days. Cases referred to the Unit are discussed during the meeting. The MTD will propose the appropriate management options on the basis of pathological reports, clinical and biochemical assessments and risk benefit evaluations. The final decision will be made by patients informed by one of the clinicians.

6. The Prostate Cancer Unit is in possession of or has easy direct access to all requirements for a complete, adequate and high level management in all phases of PC.

The inclusion of radiologists in the core team of our Unit is justified by the growing role of a morphologic-functional imaging (multiparametric magnetic resonance, PET-CT) for the management of PC. These two imaging tools have proven to be useful in the management of various aspects of PC natural history [17-19].

From the available evidences, patients with different cancers who are managed by MDT can experience better clinical outcomes [20,21]. One of the first advantages described by patients referred to the Prostate Cancer Unit is an easier availability, enhanced coordination and reduced delays to conclude the diagnostic and therapeutic item. This is likely to result in a better outcome for PC patients as early intervention is particularly crucial in cancer management [20].

The establishment of Prostate Cancer Units could provide financial saving, avoid inappropriate procedures, improve outcomes delivering high-quality care to patients.

Comparison between and a multidisciplinary and a monodisciplinary approach to PC

We analysed the characteristics of patients included in our Prostate Cancer Unit, some results obtained from the early diagnosis program, the distribution of PC cases in the different treatment options, during the first year of institution of our Unit.

These data were compared with those obtained in a mono-disciplinary urological service, offered in the same period and in the same institution (Policlinico Umberto I Hospital, University Sapienza of Rome, Italy) to the patients. The same diagnostic and therapeutic tools were available for clinicians and patients considered in the Prostate Unit or in the mono-disciplinary urological service. Patients referred to our institution are free to choose one of the two services.

From January 2011 to April 2012, 292 cases with a mean age of 62.6±11.0 years (median 64 years; range 43-76 years) were considered suitable and included by our MDT in the Prostate Cancer Unit (Group A). Of these, 145 were subjects in which the diagnosis was as yet un-established but whose could benefit from an early diagnosis program and 147 were cases in which the diagnosis of PC was already histologically confirmed and whose could be considered for treatment planning or follow-up.

One hundred fourty-five cases in which the diagnosis was un-established (mean age 60.1±7.6 years; median 57 years, range 43-69 years) were included in a early diagnosis program for PC. Mean time for concluding all the initial program till the histological diagnosis at prostate biopsy (when indicated) was 22.3±5.4 days (median 21 days, range 16-32 days). Clinical characteristics and diagnostic results of this population are presented in Table 1 and compared with those of a population (Group B) submitted, in the same period and institution, to a no-MDT organized mono-disciplinary urological evaluation for the early diagnosis of PC. In Group B mean time for concluding all the initial program till the histological diagnosis at prostate biopsy (when indicated) was 32.7±6.6 days (median 33 days, range 23-42 days).

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases with an un-established diagnosis included in the early diagnosis program of our Prostate Cancer Unit (Group A) compared with those of cases included in a similar program of a mono-disciplinary urological service (Group B). Values are reported as number (% of cases), mean SD (median) and range

| Parameter | Group A | Group B | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases | 145 | 124 | |

| Age (years) | 60.1±7.6 (57), 43-69 | 65.4±6.8 (63), 51-72 | <0.0001 |

| Familiarity | 28 (19) | 22 (18) | -- |

| Total PSA (ng/ml) | 10.8±7.8 (6.7), 2.5-21.4 | 16.5±8.4 (13.5), 4.7-28.5 | <0.0001 |

| Suspicious DRE | 23 (16) | 30 (24) | -- |

| Number of multiparametric MRI | 88 (61) | 50 (40) | -- |

| Indication for biopsy | 93 (64) | 64 (52) | -- |

| Number of PCA3 test | 25 (17) | 14 (11) | -- |

| Time to conclude the diagnostic item (days) | 22.3±5.40 (21), 16-32 | 32.7±6.6 (33), 23-42 | <0.0001 |

In both services diagnostic tools available to determine whether to indicate a prostate biopsy, were PSA serum determination, PCA3 determination, digital rectal examination (DRE), multiparametric MRI. In both services, a 14-cores random transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy was used and also multiparametric MRI results could be used for additional targeted samples (7). In particular the rate of biopsy indications and that of PC positive biopsies was 64% and 45% respectively for cases included in Group A and 52% and 41% for cases included in Group B. Interviewing clinicians of the Prostate Cancer Unit and those of the mono-disciplinary urological service, all cases indicated for biopsy in Group B should be considered for biopsy also in Group A whereas only 76% of cases indicated for biopsy in Group A should be confirmed in Group B.

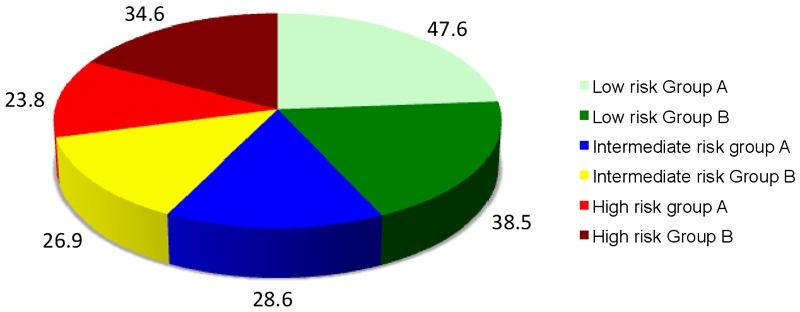

The distribution of the newly diagnosed PC cases in risk categories (8) is shown in Figure 1. A higher percentage of cases (47.6%) referred to our MDT were in the low risk group.

Figure 1.

Distribution of newly diagnosed PC in risk categories. Group A: From MDT evaluation. Group B: From mono-disciplinary urological evaluation.

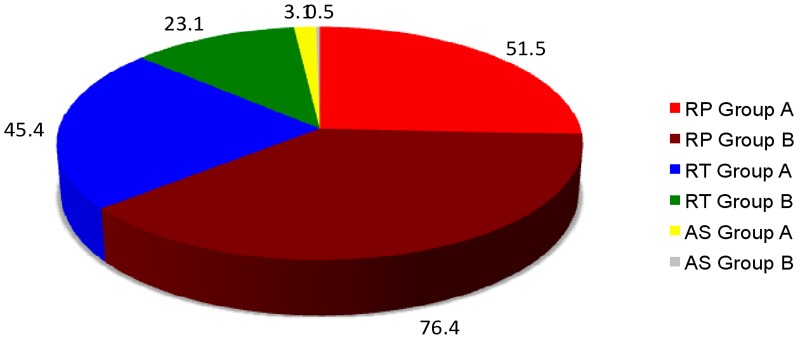

Figure 2 represent the distribution of PC cases from Group A and B who were offered radical prostatectomy, radiotherapy or active surveillance as primary therapies. In particular in the Prostate Cancer Unit (Group A) the indications for primary therapies were more distributed between surgery (51.5%) and radiotherapy (45.4%). In all low risk PC cases, active surveillance was offered as primary treatment; however the percentage of cases who accepted was very low (3.1%).

Figure 2.

Distribution of PC cases from Group A (MDT evaluation) and B (mono-disciplinary urological evaluation) who were offered radical prostatectomy (RP), radiotherapy (RT) or active surveillance (AS) as primary therapies.

To evaluate patient satisfaction in the Prostate Cancer Unit, the cases were asked to complete a satisfaction questionnaire, covering: waiting time, accessibility and comfort to all procedures required, observance of scheduling, care by the clinical staff, information given by the staff and overall satisfaction. For each item, 5 ratings were possible (from 1 (very poor) to 5 (very high)). At now the mean scores ranged between 4.14 and 4.75 and the mean overall satisfaction score was 4.45.

Conclusions

The future of PC patients relies in a successful multidisciplinary collaboration between experienced physicians which can led to important advantages in all the phases and aspects of PC management.

The establishment of Prostate Cancer Units could provide financial saving, avoid inappropriate procedures, improve outcomes delivering high-quality care to patients. These aspects are particularly relevant considering the high-incidence of PC as one of the most important medical problems facing the male population.

Acknowledgements

To all components of our prostate cancer unit (in particular: Prof Antonio Ciardi (pathologist), Prof Mauro Ciccariello (urologist-radiologist), Prof Tombolini (radiotherapist), Dssa Musio (radiotherapist), Prof Carlo Catalano (radiologist), Dr Flavia Longo (oncologist) and Prof Enrico Cortesi (oncologist)).

References

- 1.Heidenreich A, Bastian PJ, Bellmunt J, Bolla M, Joniau S, Mason MD, Matveev V, Mottet N, vander Kwast TH, Wiegel T, Zattoni F. EAU guidelines on prostate cancer Part I. Eur Urol. 2011;59:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellardita L, Donegani S, Spattezzi AL, Valdagni R. Multidisciplinary versus one-on-one setting: a qualitative study of clinicians’ perceptions of their relationship with patients with prostate cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7:e1–5. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gomella LG, Lin J, Hoffman-Censis J, Dugan P, Guiles F, Lallas CD, Singh J, McCue P, Showalter T, Valicenti RK, Dicker A, Trabulsi EJ. Enhancing prostate cancer care through the multidisciplinary clinic approach: a 15-year experience. J Oncol Pract. 2010;6:e5–e10. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2010.000071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Montagut C, Albanell J, Bellmunt J. Prostate cancer multidisciplinary approach: a key to success. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;68(Suppl 1):S32–36. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molyneux J. Interprofessional teamworking: What makes teams work well? J Interprof Care. 2001;15:29–35. doi: 10.1080/13561820020022855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosel D, Shamp MJ. Enhancing quality improvement in team effectiveness. Qual Manag Health Care. 1993;1:47–57. doi: 10.1097/00019514-199301020-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magnani T, Valdagni R, Salvioni R, Villa S, Bellardita L, Donegani S, Nicolai N, Procopio G, Bedini N, Rancati T, Zaffaroni N. The 6-year attendance of a multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinic in Italy: incidence of management changes. BJU Int. 2012 Oct;110:998–1003. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.10970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stewart SB, Bañez LL, Robertson CN, Freedland SJ, Polascik TJ, Xie D, Koontz BF, Vujaskovic Z, Lee WR, Armstrong AJ, Febbo PG, George DJ, Moul JW. Utilization trends at a multidisciplinary prostate cancer clinic: initial 5-year experience from the Duke Prostate Center. J Urol. 2012 Jan;187:103–8. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aizer AA, Paly JJ, Zietman AL, Nguyen PL, Beard CJ, Rao SK, Kaplan ID, Niemierko A, Hirsch MS, Wu CL, Olumi AF, Michaelson MD, D’Amico AV, Efstathiou JA. Multidisciplinary care and pursuit of active surveillance in low-risk prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012 Sep 1;30:3071–6. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore MJ, O’Sullivan B, Tannock IF. How expert physicians would wish to be treated if theyhad genitourinary cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 1988;6:1736–1745. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1988.6.11.1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fowler FJ Jr, McNaughton Collins M, Albertsen PC, Zietman A, Elliott DB, Barry MJ. Comparison of recommendations by urologists and radiation oncologists for treatment of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2000 Jun 28;283:3217–22. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.24.3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Payne HA, Gillatt DA. Differences and commonalities in the management of locally advanced prostate cancer: results from a survey of oncologists and urologists in the UK. BJU Int. 2007 Mar;99:545–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fennell ML, Das IP, Clauser S, Petrelli N, Salner A. The organization of multidisciplinary care teams: modeling internal and external influences on cancer care quality. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2010;2010:72–80. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgq010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basler JW, Jenkins C, Swanson G. Multidisciplinary management of prostate malignancy. Curr Urol Rep. 2005;6:228–234. doi: 10.1007/s11934-005-0012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilt TJ, Ahmed HU. Prostate cancer screening and the management of clinically localized disease. BMJ. 2013 Jan 29;346:f325. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valdagni R, Peter A, Bangma C, Drudge-Coates L, Magnani T, Moynihan C, Parker C, Redmond K, Sternberg CN, Denis L, Costa A. The requirements of a specialist Prostate Cancer Unit: a discussion paper from the European School of Oncology. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sciarra A, Barentsz J, Bjartell A, Eastham J, Hricak H, Panebianco V, Witjes JA. Advances in magnetic resonance imaging: how they are changing the management of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2011 Jun;59:962–77. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2011.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picchio M, Giovannini E, Messa C. The role of PET/computed tomography scan in the management of prostate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2011 May;21:230–6. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e328344e556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Flessing A, Jenkins V, Cat S, Fallowfield L. Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective? Lancet Oncol. 2006;7:935–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70940-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Houssami N, Sainsbury R. Breast cancer: multidisciplinary care and clinical outcomes. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:2480–91. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davies AR, Deans DAC, Penman I, Plevris JN, Fletcher J, Wall L, Phillips H, Gilmour H, Patel D, de Beaux A, Paterson-Brown S. The multidisciplinary team meeting improves staging accuracy and treatment selection for gastro-esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2006;19:496–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]