Abstract

African Americans living in the southern United States are disproportionately affected by HIV infection. Identifying and treating those who are infected is an important strategy for reducing HIV transmission. A model for integrating rapid HIV screening into community health centers was modified and used to guide implementation of a testing program in a primary care setting in a small North Carolina town serving a rural African American population. Anonymous surveys were completed by 138 adults who were offered an HIV test; of the 100 (72%) who accepted an HIV test, 61% were female and 89.9% were African American. Among those African American survey respondents who accepted an offer of testing, 58% were women. The most common reason for declining an HIV test was lack of perceived risk; younger patients were more likely to get tested. Implementation of the testing model posed challenges with time, data collection, and clinic flow.

Keywords: African American, HIV, rural, screening, south, primary care

HIV infection continues to be a significant worldwide source of morbidity and mortality in spite of advances in the medical management of people living with HIV (PLWH) infection; within the United States, the South has been disproportionately affected by the epidemic (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2011). According to the 2009 HIV/AIDS surveillance data from the CDC, 8 of the 10 states reporting the highest rates of new HIV infections were in the South, 46% of new AIDS diagnoses were in the South, and half of the newly reported cases of HIV were in the South (CDC, 2011). Of the 40 states and 5 territories that reported new HIV diagnoses in 2009, North Carolina ranked eighth with 23.8 new infections per 100,000 population, slightly higher than the overall U.S. rate of 21.1 per 100,000, and the rate of AIDS diagnoses was the eleventh highest in the country (North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services [NCDHHS], 2011). Since the early 1990s, roughly 25% of HIV-infected persons in North Carolina have lived in rural areas (NCDHHS, 2009). In 2006 North Carolina had the highest reported rates among rural areas within the United States for both HIV infection and AIDS, and rural Vance County, where this project was conducted, had the twelfth highest rate of newly reported HIV-infected individuals in the state between 2008 and 2010 (NCDHHS, 2011).

North Carolina has the eighth highest percentage of the African American population in the United States, and in 2010 the rate of new HIV infections among adult/adolescent African Americans in North Carolina was more than 10 times greater than the rate of new infections among adult/adolescent Whites (NCDHHS, 2011). The highest rate of new infections in 2010 in North Carolina was found among adult/adolescent African American males (94.0 per 100,000 population), and the largest disparity in HIV diagnoses in North Carolina existed between adult and adolescent White and African American females; the 2010 HIV rate for African American females was approximately 17 times higher than White, non-Hispanic females (NCDHHS, 2011).

The risk of HIV transmission in North Carolina is highest among men who have sex with men (MSM) who accounted for 75% of new adult/adolescent HIV cases in 2010; African American MSM had nearly twice the number of cases as White non-Hispanic MSM. Heterosexual transmission, which accounted for 95% of cases among adult/adolescent females, accounted for 21% of all new cases in 2010 (NCDHHS, 2011).

It is estimated that 20% of the nearly 1.2 million PLWH in the United States do not know their HIV antibody status, and therefore may unknowingly infect others (CDC, 2011); those who are unaware of their HIV status account for an estimated 54%-70% of new infections (Marks, Crepaz, & Janssen, 2006). Additionally, 40% to 50% are being diagnosed late in infection with CDC-defined AIDS (Krawczyk et al., 2006; Mugavero, Castellano, Edelman, & Hicks, 2007). Treatment for HIV infection substantially reduces morbidity and mortality; early initiation of antiretroviral therapy can reduce a person’s risk of transmitting the virus to an uninfected partner by as much as 96% (Cohen et al., 2011), and becoming aware of one’s HIV status is known to lead to behavior changes that reduce the risk of transmission (Marks, Crepaz, Senterfitt, & Janssen, 2005; Weinhardt, Carey, Johnson, & Bickham, 1999). All of these facts underscore the need for effective HIV prevention and screening strategies.

In 2006 the CDC issued a recommendation that all people ages 13-64 should be offered HIV antibody testing as a routine part of primary care (Branson et al., 2006). In response to and in support of those recommendations the National Association of Community Health Centers (NACHC) conducted a pilot implementation study of HIV testing programs in six community health centers in Mississippi, North Carolina, and South Carolina from December 2006 through April 2008 (Myers, Modica, Dufour, Bernstein, & McNamara, 2009). The success of that pilot led to the development of an innovative national model for integrating HIV screening into routine primary care (Modica, 2009). The NACHC model integrated routine testing into a clinic’s workflow utilizing existing staff, while adding only a few minutes to the patient visit.

A privately-owned primary care clinic (referred to in this paper as PCC) and the Northern Outreach Clinic (NOC), a grant-funded HIV clinic with a staff skilled in rapid HIV testing, are located in the town of Henderson, NC, the county seat of rural Vance County. The two clinics, which provide care for a predominantly underserved African American population, joined together to integrate a routine HIV screening program adopted from the NACHC testing model in February and March of 2012 at the PCC, utilizing rapid HIV testing kits provided by the North Carolina Rapid HIV Testing Program.

The primary aim of this project was to increase HIV testing in the Henderson community and surrounding rural area by integrating rapid HIV testing into the primary care setting. The second aim of the project was to examine the relationship between sociodemographic variables and acceptance of HIV testing. In this paper the HIV testing rates for the first 7 weeks of project implementation are reported, the challenges involved in the planning and initial implementation of the project are described, and the sociodemographic variables associated with test acceptance that were derived from survey data are discussed.

Methods

Study Sample

Between February 1 and March, 20, 2012, 100 patients underwent rapid HIV antibody testing at the PCC by a team of nursing and medical assistants during routine office visits.

Anonymous surveys regarding sociodemographic variables and routine HIV testing were completed by 138 adult patients who were offered a test; patients were asked to complete the survey regardless of whether or not they chose to undergo testing.

Setting

Henderson, NC, had a population of 15,368 in 2010, of which 55.6% were female, 64% were African American, and 30% were White. From 2006-2010 median household income was $26,164 and 33.3% of the population lived below the federal poverty level (U.S. Census Bureau, 2012). The primary care clinic where the project was conducted is the oldest African American-owned private medical practice in the community, and the clinic serves a predominately African American clientele from Henderson and the surrounding rural area. Our project was unique in this geographic area as no other primary care practices had routinized the practice of HIV screening. It was also unique in that the population under focus represented a constellation of social factors that influence health and behavior such as religion, racial minorities, poverty, low literacy, homophobia, and stigma.

Project Implementation

The implementation plan for this project was adopted from the NACHC model for integrating routine HIV screening into community health centers (Modica, 2009). The model was designed to coordinate the implementation process over a 90-day timeline. Eight essential steps were outlined, including guidance in how to (a) build the infrastructure for testing, (b) establish essential links and partnerships, (c) develop quality assurance standards, (d) organize the patient flow process, (e) solidify a protocol for handling reactive test results, (f) finalize data collection methods, (g) train the staff, and (h) launch the project. Table 1 summarizes the key elements and primary implementation tasks involved in each step.

Table 1.

Implementation Plan for Rapid HIV Testing Adapted from the NACHC Model

| Essential Steps | Key Elements | Implementation Plans |

|---|---|---|

| Step 1: Pre-Work |

|

|

| Step 2: Set up the Framework |

|

|

| Step 3: Design the Patient Visit Process to Include HIV Screening |

|

|

| Step 4: Plan for Tracking Reactives |

|

|

| Step 5: Adopt HIV Screening Codes for Reimbursement |

|

|

| Step 6: Commit |

|

|

| Step 7: Launch |

|

|

| Step 8: Realignment |

|

|

Note. CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; PCC = primary care clinic; NOC = Northern Outreach Clinic (HIV clinic); WB = Western blot; NC = North Carolina; NCDIS = North Carolina Disease Intervention Specialist; NACHC = National Association of Community Health Centers; QI = quality improvement.

Data Collection

Each time a test was offered, testers were responsible for entering into the electronic medical record whether or not the test was accepted, and the results of the test. When a patient accepted a rapid HIV test, the tester was responsible for recording the following information in a test results log: patient ID, test date, test lot number, developing time, test result (negative, reactive, or invalid), presence of built-in control, and the name of the tester/reader.

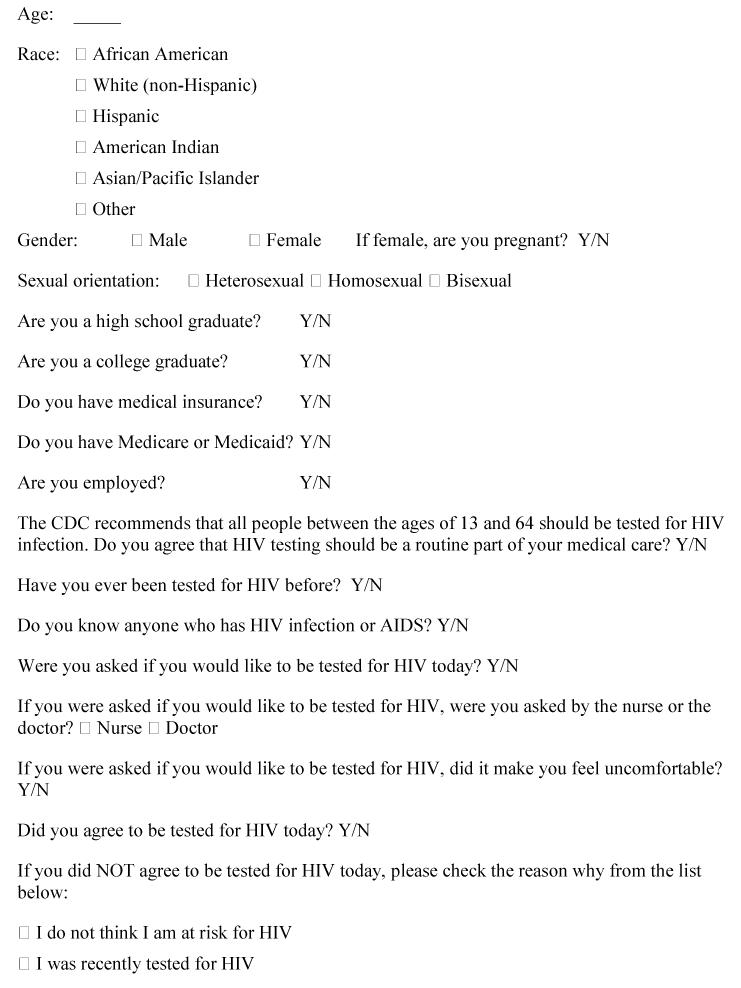

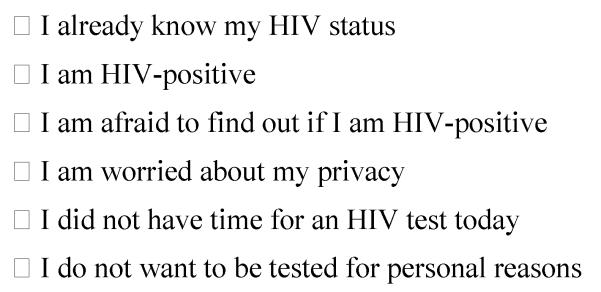

After being offered an HIV test, patients were asked to complete an anonymous survey that captured self-reported sociodemographic data, and, for those who declined an offer of HIV testing, the reason(s) that testing was refused. In the original NACHC testing model that information was gathered by the testers and entered onto a paper data collection sheet. We decided to collect those data by means of a survey because we thought patients might be more honest about why they refused an offer of testing if they were able to list the reason(s) anonymously. The survey (Figure 1), which was derived primarily from the NACHC model and developed by the first author, was reviewed by six faculty members at the Duke University School of Nursing prior to being approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board (IRB). Although rapid testing was offered to anyone 13 years and older in keeping with CDC recommendations, survey data were collected only on patients 18 years and older (no minors), which was an IRB restriction. To collect data on patients younger than age 18, we would have been required to obtain written informed consent; introducing written informed consent into the testing process would have posed a significant barrier to rapid HIV testing. Survey data were transferred from paper to an electronic database utilizing REDCap™ (Research Electronic Data Capture) software and stored on a secure server at the Duke University School of Nursing. Data were converted to an Excel format prior to being downloaded to Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for analysis.

Figure 1.

HIV testing survey.

Data Analysis and Results

A number of discrepancies in the data were extracted from the PCC electronic medical records due to inconsistencies in data collection and reporting, particularly during the first 3 weeks of testing, so meaningful use of those data was not possible. Therefore, data analysis for this paper is restricted to data that were obtained from the surveys only.

Between February 1 and March 20, 2012, 138 patients were offered an HIV test and then asked to complete an anonymous survey. One hundred (72%) of the survey respondents agreed to be tested. There were no invalid or reactive test results. Among those who declined an offer of testing, 35/38 (92%) chose to list their reason (Table 2). I do not think I am at risk was the most common reason (28.6%), followed by I already know my status (25.7%), I was recently tested for HIV (22.9%), I do not want to be tested for personal reasons (14.3%), I did not have time for an HIV test today (5.7%), and I am worried about my privacy (2.8%).

Table 2.

Reasons Cited by Survey Respondents (n = 35)a for Declining an Offer of HIV Testing

| Reason for Declining an Offer of HIV Testing | Respondents Citing Each Reason |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| “I do not think I am at risk” | 10 (28.6) |

| “I already know my status” | 9 (25.7) |

| “I was recently tested for HIV” | 8 (22.9) |

| “I do not want to be tested for personal reasons” | 5 (14.3) |

| “I did not have time for an HIV test today” | 2 (5.7) |

| “I am worried about my privacy” | 1 (2.8) |

Note.

35 (92%) of the 38 respondents who declined testing cited a reason.

The mean age of the survey respondents was 43.55 years (SD = 14.86). Sixty-one percent were female and most of the participants were African American (89.90%). The aim of the survey analysis was to understand sociodemographic factors contributing to one’s agreement (Yes/No) to undergo HIV testing.

To determine the relationship between variables of interest and agreement to undergo testing, a logistic regression was conducted, using backward conditional elimination. Given the exploratory nature of the study, we included 11 predictor variables (Table 3) although the suggested sample size is 10 participants per predictor (Peduzzi, Concato, Kemper, Holford, & Feinstein, 1996). Included in the model were age, race, gender, sexual orientation, high school graduate, college graduate, medical insurance recipient, knowing someone with HIV, employment status, agreement with CDC recommendations, and experience with HIV testing prior to this visit. Each categorical predictor variable was recoded as necessary to reflect a status of 1= presence of the variable and 0 = absence of the variable. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistical Analysis software version 19.

Table 3.

HIV Screening Survey Variables of Interest Included in Logistic Regression Analysis

| Survey Variable (number of respondents who answered question) | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age in years (n = 136) | 43.55 | 14.86 |

|

|

||

| n (%) | ||

| Race (n = 133) | ||

| African American | 124 (89.9) | |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 7 (5.0) | |

| Hispanic | 1 (0.7) | |

| American Indian | 0 (0.0) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | |

| Gender (n = 136) | ||

| Female | 83 (61.0) | |

| Male | 53 (39.0) | |

| Sexual orientation (n = 89) | ||

| Heterosexual | 76 (85.4) | |

| Bisexual | 9 (10.1) | |

| Homosexual | 4 (4.5) | |

| High school graduate (n = 132) | ||

| Yes | 78 (59.0) | |

| No | 54 (41.0) | |

| College graduate (n = 90) | ||

| Yes | 4 (4.4) | |

| No | 86 (95.6) | |

| Medical insurance (n = 115) | ||

| Yes | 82 (71.3) | |

| No | 33 (28.7) | |

| Know anyone with HIV or AIDS (n = 134) | ||

| Yes | 33 (24.6) | |

| No | 101 (75.4) | |

| Employed (n = 126) | ||

| Yes | 83 (65.9) | |

| No | 43 (34.1) | |

| Agree that HIV testing should be a routine part of primary care (n = 127) | ||

| Yes | 112 (88.2) | |

| No | 15 (11.8) | |

| Previously tested for HIV (n = 131) | ||

| Yes | 73 (55.7) | |

| No | 58 (44.3) | |

Results revealed that age was significantly related to agreement to undergo testing (final model η2 [n = 138] = 13.79, p < .001). Specifically, an increase of 1 year in age corresponded to a 6% decrease in the odds of a person agreeing to be tested. All other variables were non-significant in the overall model.

Discussion

An emerging body of evidence composed primarily of pre- and post-implementation testing data has suggested that HIV testing rates improve in a variety of health care settings when a universal approach to screening is adopted (Anaya et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2007; Criniti, Aaron, Hilley, & Wolf, 2011; Cunningham et al., 2009; Liddicoat, Losina, Kang, Freedberg, & Walensky, 2006; Myers et al., 2009; Walensky et al., 2011; Weis et al., 2009). The study in the Southeast by Myers and colleagues (2009) that led to development of the NACHC model reported an overall 67% HIV test acceptance rate that ranged from 56% to 83% across centers during a 13-month period, which represented a nearly 3-fold increase in testing compared to the prior year.

A number of barriers to implementing the CDC recommendations for routine HIV screening have been identified and reported in the literature. These include state and/or local laws that interfere with the CDC recommendations for testing, concerns about pre-test and post-test counseling, fear of discrimination, stigma associated with an HIV diagnosis, cost of testing and the perception that risk-based HIV testing is more cost-effective, and lack of effective mechanisms to link newly diagnosed HIV-infected patients to care (Bartlett et al., 2008). The absence of several of these barriers facilitated success for our particular project: North Carolina law no longer requires separate written consent or pre- and post-test counseling for HIV testing, test kits were provided free by the North Carolina Rapid HIV Testing Program in exchange for data reporting to the CDC, and anyone who was identified as HIV-infected at the PCC had a direct link to comprehensive HIV care through the NOC.

Several challenges arose during early implementation of this project that deserve mention. First, the 90-day timeline for implementation proved to be insufficient for the amount of preparation that was required; coordinating schedules and organizing the necessary groups of people was more time-consuming and difficult than anticipated. In addition to the groundwork outlined in the implementation plan, certain requirements for participating in the North Carolina Rapid HIV Testing Program had to be met, including submission of a Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certificate of waiver, obtaining a certificate for HIV testing, making sure that quality assurance measures were in compliance with the program’s requirements, and ordering and receiving test kits from the state-run program. Once the December 1, 2011, target implementation date had passed, it became increasingly difficult to coordinate the final steps due to erratic holiday schedules, and testing did not begin until February, 2012. A 6-month goal for implementation would have been more reasonable.

A second problem that occurred during early project implementation concerned data collection. Although training sessions with PCC staff included the data collection process, data collection and entry into the electronic medical record was inconsistent among the testers, especially in the first 3 weeks of testing, which compromised the ability to conduct certain analyses such as comparing total acceptance/refusal rates. Inconsistencies in data collection and recording were cited as potential limitations when rapid testing was implemented at community health centers in South Carolina (Weis et al., 2009), although nurses involved in that study were not trained in data collection procedures. In the original NACHC model, all data, including reasons for test refusal, are collected by testers and entered onto a single data collection sheet. Perhaps having a single data sheet to complete, as opposed to administering a survey and entering data into a log book and the electronic medical record, would have streamlined the data collection process and allowed for more consistency in recording.

A third problem concerned patient volume and flow. Patients were scheduled every 15 minutes at the PCC, and unscheduled walk-in patients were always accommodated. When the clinic was particularly busy, when they were running behind schedule, or when emergent issues arose, the testers felt there was insufficient time to perform the test. Lack of time has been cited in the literature as a barrier to routine testing (Demarco, Gallagher, Bradley-Springer, Jones, & Visk, 2012; Thornton et al., 2012). In a recent study of routine HIV testing in a primary care clinic that reported a low rate of HIV testing (8.75%), a survey of health care workers who participated in testing revealed that busy days or days when the clinic was short-staffed resulted in fewer tests being offered (Valenti, Szpunar, Saravolatz, & Johnson, 2012).

In our survey analysis we found that younger patients were more likely than older patients to undergo testing. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF, 2011), 2009 Survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS, showed that younger adults were more likely to undergo testing than older adults. Younger age has been associated with higher test acceptance rates in other studies (Brown et al., 2007; Cunningham et al., 2009; Valenti et al., 2012; Weis et al., 2009), and age has been shown to be negatively associated with HIV testing in at-risk African American women in particular (Akers, Bernstein, Henderson, Doyle, & Corbie-Smith, 2007).

The majority of those who accepted an offer of HIV testing in this study were African American women, so we were successful in reaching that particular group at high risk for HIV infection. We were not, however, successful in reaching African American MSM, the group at highest risk in the South. This may have been due in part to lower numbers of MSM seeking medical care. Perhaps adopting a strategy of home-based HIV testing would better reach those who do not routinely seek out medical care, or those in rural areas who may live far away from testing sites. This type of strategy has proved to be effective in rural areas of Malawi (Helleringer, Kohler, Frimpong, & Mkandawire, 2009) and Uganda (Menzies et al., 2009), and home-based testing as part of online HIV prevention research has been shown to be acceptable with high-risk MSM in the United States (Sharma, Sullivan, & Khosropour, 2011).

Regarding stigma associated with HIV testing, the KFF (2011) 2009 survey reported that 69% of the public (up from 62% in 2006) felt that being tested would not make a difference in how people they knew would think of them, yet those who perceived a threat of testing-related stigma (those who felt people they knew would think less of them if it were found out they had been tested) were much less likely to have ever undergone testing in the first place. Although the stigma surrounding HIV testing was not addressed in our survey, respondents were asked about sexual orientation, and interestingly, only 89/138 (64.5%) chose to disclose their sexual orientation (76 heterosexual, 9 bisexual, and 4 homosexual), which may reflect the fear of stigma associated with homosexuality that is prevalent within African American communities (Glick & Golden, 2010). The low response rate to the question of sexual orientation may have also been influenced by how the question was asked. The Sexual Minority Assessment Research Team (SMART), a multidisciplinary panel of experts that has explored the question of how to ask about sexual orientation, has recommended a question developed and tested by researchers at the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). The question reads: Do you consider yourself to be: a) Heterosexual or straight; b) Gay or lesbian; or c) Bisexual? (Badgett, 2009, p. 8). The SMART panel also discouraged the use of the terms sexual orientation or sexual identity in the stem of the question as it confused many respondents (Badgett, 2009). Perhaps avoiding the term sexual orientation and including the terms gay, lesbian, or straight would have yielded a higher response rate.

Lack of perceived risk was the most common reason our survey respondents cited for not accepting an HIV test, which was consistent with what has been seen in other studies (Akers et al., 2007; Cunningham et al., 2009; McCoy et al., 2009; Myers et al., 2009; Weis et al., 2009). Similarly, 69% of respondents to the KFF (2011) 2009 survey who said they had never been tested cited not being at risk as their reason. Future research should explore strategies for increasing HIV risk awareness in PCC clinic attendees (many of whom comprise identified at-risk groups), such as increasing visibility of posters and other patient education materials in patient waiting areas and examination rooms. Other commonly cited reasons in our survey for test refusal were current knowledge of HIV status and having been recently tested. And lastly, in the KFF (2011) 2009 survey, 27% said that they never underwent HIV testing because their doctor had never recommended it, a finding that further supported a routine testing strategy over traditional targeted, risk-based testing. Prior to project implementation, the PCC did not routinely ask patients if they would like an HIV test; testing was performed only if the patient requested it, if the provider determined the patient to be at risk, or if the patient presented with a symptom complex that suggested HIV infection. Simply asking patients if they would like to have an HIV test in the PCC resulted in increased screening rates.

Greenhalgh, Robert, Bate, Macfarlane, and Kyriakidou (2005) identified a number of key attributes that facilitated successful innovations and predicted sustainability, and a number of these attributes characterized the NACHC model and its adoption in the PCC. There are obvious relative advantages to adoption: (a) increased testing can lead to earlier identification of HIV infection and a corresponding reduction in HIV morbidity, mortality, and transmission in the community; (b) the testing program is compatible with the existing organizational structure and the adopters’ values; (c) rapid HIV testing demonstrates low complexity, trialability, and observability; and (d) the NACHC model is malleable and easy to modify. One of the nursing assistants offering and performing rapid testing at the PCC emerged as a “champion” during the study, and the PCC had a direct link to HIV clinical care through the NOC. Both of these factors have positively influenced sustainability of rapid HIV testing programs in other clinical settings (Criniti et al., 2011). Other factors that may positively influence the sustainability of the current project include the availability of free rapid test kits in exchange for data reporting to the CDC, and the ability to purchase kits and bill for testing should the supply of test kits from the North Carolina Rapid HIV Testing Program be interrupted. A primary threat to sustainability is the impact on clinic work flow; therefore, a strategy of including rapid HIV testing in a battery of routine yearly screenings may be a more sustainable alternative in busy primary care settings.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study is the lack of baseline data, specifically the HIV testing rate at the PCC before project implementation. Anecdotally, only a few patients had been screened for HIV infection during the previous year, and none of those screenings was a routine part of primary care. Another limitation was the lack of accurate data regarding the number of patients who are routinely seen at the PCC, and the number of patients seen during the time of data collection, which made it impossible to ascertain the actual percentage of patients seen during the time period who were offered a test. The lack of an accurate demographic profile of the PCC patient population was also a limitation, which made it difficult to determine if the large number of African American women and the small number of MSM who were tested reflected the PCC clientele.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

Early implementation of the NACHC model in our setting posed challenges in terms of time involved in initial planning, consistent data collection and reporting, and patient flow. In spite of these challenges, 100 patients were screened for HIV infection who might not have been screened otherwise, and they were given HIV risk reduction handouts after testing, an education intervention that may raise awareness and lead to behavior changes. Younger patients were more likely to undergo testing. The majority of patients who were tested, African American women, represented a high-risk group in North Carolina and the South, and yet African American MSM, those with the highest risk, were underrepresented in our sample. Although nurse-led rapid HIV testing has been shown to be an effective strategy and the NACHC model has been shown to be effective in community health center settings, more studies are needed to establish best practices for HIV screening in busy rural primary care settings, and novel strategies are needed for increasing testing rates among MSM.

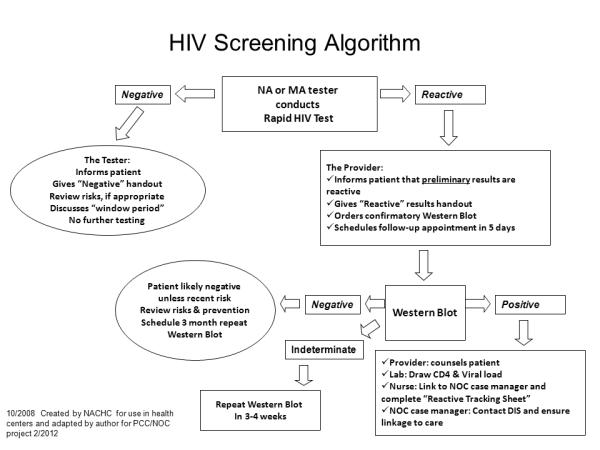

Figure 2.

HIV screening algorithm.

Note. NA = nursing assistant; MA = medical assistant; NOC = Northern Outreach Clinic; DIS = Disease Intervention Specialist; NACHC= National Association of Community Health Centers.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the following for their time and commitment to this project: Dr. James Kenney, the nursing and administrative staff, and the patients at Beckford Medical Center in Henderson, NC; the staff of the Northern Outreach Clinic in Henderson, NC; Pamela Klein and Janet Alexander with the North Carolina Rapid HIV Testing Program; and Elizabeth P. Flint, PhD, Duke University School of Nursing.

Footnotes

Disclosure.

James L. Harmon, Michelle Collins-Ogle, Julie Thompson, and Julie Barroso report no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest. John A. Bartlett receives salary support from the following grants: Health Resources and Services Administration T84HA21123, National Cancer Institute D43CA153722, National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases P30AI064518, National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases U01AI069484, and the Fogarty International Center D43TW06732.

Contributor Information

James L. Harmon, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC, USA.

Michelle Collins-Ogle, Clinical Director of Infectious Disease, Warren-Vance Community Health Center, Henderson, NC, USA.

John A. Bartlett, Global Health, and Nursing, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA.

Julie Thompson, Developmental Research Psychologist, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC, USA.

Julie Barroso, Duke University School of Nursing, Durham, NC, USA.

References

- Akers A, Bernstein L, Henderson S, Doyle J, Corbie-Smith G. Factors associated with lack of interest in HIV testing in older at-risk women. Journal of Womens Health. 2007;16(6):842–858. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.0028. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anaya HD, Hoang T, Golden JF, Goetz MB, Gifford A, Bowman C, Asch SM. Improving HIV screening and receipt of results by nurse-initiated streamlined counseling and rapid testing. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(6):800–807. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0617-x. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0617-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badgett MVL. Best practices for asking questions about sexual orientation on surveys. 2009 Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/706057d5.

- Bartlett JG, Branson BM, Fenton K, Hauschild BC, Miller V, Mayer KH. Opt-out testing for human immunodeficiency virus in the United States: Progress and challenges. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2008;300(8):945–951. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.8.945. doi:10.1001/jama.300.8.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, Clark JE. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. Morbidity and Mortablity Weekly Reports, Recommendations and Reports. 2006;55(RR-14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, Bahn M, Czarnogorski M, Kuo I, Sikka N. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines: Results from a high-prevalence area. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2007;46(4):395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV surveillance report, 2009. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, Fleming TR. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criniti SM, Aaron E, Hilley A, Wolf S. Integration of routine rapid HIV screening in an urban family planning clinic. Journal of Midwifery & Womens Health. 2011;56(4):395–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00031.x. doi:10.1111/j.1542-2011.2011.00031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Doran B, DeLuca J, Dyksterhouse R, Asgary R, Sacajiu G. Routine opt-out HIV testing in an urban community health center. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(8):619–623. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0005. doi:10.1089/apc.2009.0005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demarco RF, Gallagher D, Bradley-Springer L, Jones SG, Visk J. Recommendations and reality: Perceived patient, provider, and policy barriers to implementing routine HIV screening and proposed solutions. Nursing Outlook. 2012;60(2):72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2011.06.002. doi:10.1016/j.outlook.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SN, Golden MR. Persistence of racial differences in attitudes toward homosexuality in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2010;55(4):516–523. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f275e0. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f275e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Bate P, Macfarlane F, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in health care organizations. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; Oxford, UK: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald JL, Burstein GR, Pincus J, Branson B. A rapid review of rapid HIV antibody tests. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2006;8(2):125–131. doi: 10.1007/s11908-006-0008-6. doi:10.1007/s11908-006-0008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helleringer S, Kohler HP, Frimpong JA, Mkandawire J. Increasing uptake of HIV testing and counseling among the poorest in sub-Saharan countries through home-based service provision. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2009;51(2):185–193. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819c1726. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819c1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation 2009 survey of Americans on HIV/AIDS: Summary of findings on the domestic epidemic. 2011 Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7889.pdf.

- Krawczyk CS, Funkhouser E, Kilby JM, Kaslow RA, Bey AK, Vermund SH. Factors associated with delayed initiation of HIV medical care among infected persons attending a southern HIV/AIDS clinic. Southern Medical Journal. 2006;99(5):472–481. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000215639.59563.83. doi:10.1097/01.smj.0000215639.59563.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liddicoat RV, Losina E, Kang M, Freedberg KA, Walensky RP. Refusing HIV testing in an urgent care setting: Results from the “Think HIV” program. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2006;20(2):84–92. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. doi:10.1089/apc.2006.20.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-analysis of high-risk sexual behavior in persons aware and unaware they are infected with HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV prevention programs. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. doi:10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20(10):1447–1450. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy SI, Miller WC, MacDonald PD, Hurt CB, Leone PA, Eron JJ, Strauss RP. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing and linkage to primary care: Narratives of people with advanced HIV in the Southeast. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1313–1320. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803174. doi:10.1080/09540120902803174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzies N, Abang B, Wanyenze R, Nuwaha F, Mugisha B, Coutinho A, Blandford JM. The costs and effectiveness of four HIV counseling and testing strategies in Uganda. AIDS. 2009;23(3):395–401. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321e40b. doi:10.1097/QAD.0b013e328321e40b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modica C. Integrating HIV screening into routine primary care: A health center model. 2009 Retrieved from http://www.aidsetc.org/aidsetc?page=etres-display&resource=etres-426. [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Castellano C, Edelman D, Hicks C. Late diagnosis of HIV infection: The role of age and sex. American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(4):370–373. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.050. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JJ, Modica C, Dufour MS, Bernstein C, McNamara K. Routine rapid HIV screening in six community health centers serving populations at risk. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(12):1269–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1070-1. doi:10.1007/s11606-009-1070-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services North Carolina epidemiologic profile for HIV/STD prevention & care planning, December 2009. 2009 Retrieved from http://epi.publichealth.nc.gov/cd/stds/figures/Epi_Profile_2009.pdf.

- North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services North Carolina epidemiologic profile for HIV/STD prevention & care planning, December 2011. 2011 Retrieved from http://epi.publichealth.nc.gov/cd/stds/figures/Epi_Profile_2011.pdf.

- Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstein AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1996;49(12):1373–1379. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00236-3. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(96)00236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A, Sullivan PS, Khosropour CM. Willingness to take a free home HIV test and associated factors among Internet-using men who have sex with men. Journal of the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care. 2011;10(6):357–364. doi: 10.1177/1545109711404946. doi:10.1177/1545109711404946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton AC, Rayment M, Elam G, Atkins M, Jones R, Nardone A, Sullivan AK. Exploring staff attitudes to routine HIV testing in non-traditional settings: A qualitative study in four healthcare facilities. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2012;88(8):601–606. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2012-050584. doi:10.1136/sextrans-2012-050584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U. S. Census Bureau State & county quickfacts. 2012 Retrieved from http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/37/3730660.html.

- Valenti SE, Szpunar SM, Saravolatz LD, Johnson LB. Routine HIV testing in primary care clinics: A study evaluating patient and provider acceptance. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2012;23(1):87–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.06.005. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walensky RP, Reichmann WM, Arbelaez C, Wright E, Katz JN, Seage GR, 3rd, Losina E. Counselor-versus provider-based HIV screening in the emergency department: Results from the universal screening for HIV infection in the emergency room (USHER) randomized controlled trial. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2011;58(Suppl. 1):S126–S132. e121–e124. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.023. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinhardt LS, Carey MP, Johnson BT, Bickham NL. Effects of HIV counseling and testing on sexual risk behavior: A meta-analytic review of published research, 1985-1997. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1397–1405. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1397. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis KE, Liese AD, Hussey J, Coleman J, Powell P, Gibson JJ, Duffus WA. A routine HIV screening program in a South Carolina community health center in an area of low HIV prevalence. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23(4):251–258. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0167. doi:10.1089/apc.2008.0167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]