Abstract

Approximately 40% of college students reported engaging in heavy episodic or “binge” drinking in the 2 weeks prior to being surveyed. Research indicates that college students suffering from depression are more likely to report experiencing negative consequences related to their drinking than other students are. The reasons for this relationship have not been well-studied. Hence, the purpose of this study was to determine whether use of protective behavioral strategies (PBS), defined as cognitive-behavioral strategies an individual can use when drinking alcohol that limit both consumption and alcohol-related problems, mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. Data were obtained from 686 participants from a large, public university who were referred to an alcohol intervention as a result of violating on-campus alcohol policies. Results from structural equation modeling analyses indicated that use of PBS partially mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. Implications for clinicians treating college students who report experiencing depressive symptoms or consuming alcohol are discussed.

Keywords: college student, binge drinking, depression, structural equation modeling

A number of studies have suggested that excessive alcohol use represents a public health problem among college students in the United States (e.g., Hingson, Heeren, Winter, & Wechsler, 2005; Wechsler et al., 2002). Approximately 40% of students report engaging in heavy episodic drinking (generally defined as at least 4+ drinks for women or 5+ drinks for men in one sitting) at least once in the preceding 2 weeks (Wechsler et al., 2002). Those students who engage in heavy episodic drinking are far more likely than are other students to experience negative consequences, such as academic difficulties, unwanted or unsafe sexual activity, or trouble with police or campus authorities as a result of their drinking (Wechsler et al., 2002). Additionally, epidemiological research indicates that each year among college students alcohol is implicated in approximately 1,700 deaths from all causes (e.g., alcohol poisoning, drunk driving accidents), 500,000 unintentional injuries, and 600,000 assaults (Hingson et al., 2005). These studies suggest that understanding factors associated with alcohol use and its related negative consequences are an important line of inquiry for psychological researchers.

Research has consistently indicated that mood disorders are associated with alcohol-related disorders (Grant et al., 2004), but potential mediators of this association, especially among younger drinkers, have not been well-studied. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether a construct that is a relatively recent addition to the addictive behaviors literature, namely protective behavioral strategies (PBS), mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences in a sample of alcohol-using college students.

Depressive Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences

Studies have shown that depressive symptoms and alcohol use co-occur in the adult population. For example, a recent national epidemiological study found that those with an alcohol-use disorder were 2.3 times more likely than were those without such a disorder to meet diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder and 1.7 times more likely to meet criteria for dysthymia (Grant et al., 2004). Other studies have suggested that depressive symptoms may serve as a prospective risk factor for subsequent heavy alcohol use in adults (e.g., Dixit & Crum, 2000). Among college students, however, studies have not supported a strong association between depressive symptoms and alcohol consumption. Several studies have shown nonsignificant correlations between various alcohol use measures and depressive symptoms (e.g., Nagoshi, 1999; Patock-Peckham, Hutchinson, Cheong, & Nagoshi, 1998), and other studies have shown nonsignificant relationships between conceptually similar constructs (e.g., psychological distress, negative affect) and alcohol use (e.g., Geisner, Larimer, & Neighbors, 2004; Park & Grant, 2005).

Studies have, however, shown that among college students, a relationship exists between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., missing class, getting into trouble with authorities, or becoming ill as a result of drinking alcohol). For example, studies have reported correlations of .22–.32 between depressive symptoms and problems with alcohol (Camatta & Nagoshi, 1995; Nagoshi, 1999; Patock-Peckham et al., 1998). Other studies measuring similar constructs, like negative affect, have reported a similar pattern of results (e.g., Park & Grant, 2005). Therefore, research seems to indicate that although college students with higher levels of depressive symptoms do not drink more than other students do, they are more likely to report experiencing negative consequences as a result of their alcohol use.

PBS

Although research has established a small-to-moderate relationship in the collegiate population between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences, studies have yet to address why this relationship occurs. It is possible that one’s use of PBS at least partially explains this relationship. PBS are defined as behaviors an individual can utilize to decrease the likelihood of excessive drinking and experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences (Martens et al., 2004). These behaviors are conceptualized as changeable and amenable to intervention efforts, as they are included as components in brief intervention programs with college students (e.g., Dimeff, Baer, Kivlahan, & Marlatt, 1999). Examples of PBS include knowing where one’s drink has been at all times, avoiding trying to out-drink others, and having a designated driver.

Martens and his colleagues have conducted several studies among college students that have demonstrated a negative association between both alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences (Martens et al., 2004, 2005; Martens, Pedersen, LaBrie, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007). Studies by Delva et al. (2004) and Benton et al. (2004) corroborated these findings. Together, this body of evidence suggests that greater use of PBS is consistently associated with both less alcohol use and fewer alcohol-related negative consequences among college students.

It is possible that use of PBS at least partially mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. Although researchers have not examined the relationship between depressive symptoms and PBS, there are at least two factors that point to a relationship between the two constructs. First, individuals experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms may not be able to activate the cognitive and behavioral responses necessary to engage in PBS, thus making them more likely to experience alcohol-related negative consequences. Theories of depression have long addressed errors in cognitive judgment among depressed individuals (e.g., Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979), and a number of studies have shown that adolescents and adults experiencing depression engage in poor decision making and other problems associated with cognitive processing (e.g., Fossati, Ergis, & Allilaire, 2002; Kyte, Goodyear, & Sahakian, 2005). For example, an individual with high levels of depressive symptoms who is using alcohol may not have the cognitive ability or motivation to plan to limit his or her number of drinks or to use a designated driver. Second, many PBS involve drinking in a social situation or relying on one’s friends (e.g., having a friend let you know when you have had too much to drink, leaving a party at a specified time), and those high in depressive symptoms choosing to drink may be doing so in situations that are not conducive to using many of these PBS (e.g., drinking alone). Thus, it is possible that higher depressive symptoms result in less use of PBS, which is then associated with a greater likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related negative consequences. The purpose of the present study was to test this premise by determining whether PBS mediate the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences.

Method

Participants

Participants were 686 undergraduate students at a large, public Northeastern university who were referred to an alcohol intervention program as a result of committing an alcohol-related infraction on campus. Participants’ mean age was 18.82 years (SD = 0.81) and year in school was as follows: 48.7% were freshmen, 35.3% were sophomores, 13.4% were juniors, and 1.6% were seniors. Participants were mostly men (62.2%) and White (82.8%). Other racial and ethnic representations were as follows: 4.1% were Asian American, 2.8% were Black or African American, 3.4% were multiracial, and 7.0% identified as other. Almost all participants (97.2%) reported living in a dorm or residence hall. The mean GPA of the sample was approximately 3.0. Participants were not required to take part in the study to fulfill the requirements mandated by the judicial board as a result of their infractions. Instead, students were given the option of enrolling in a research project that included a required intervention or completing an intervention of similar duration with no research activity provided by the on-campus counseling center.

Measures

Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985)

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire, a measure commonly used to assess for alcohol consumption among college students (e.g., Larimer et al., 2001), was used to calculate participants’ average number of drinks per week. The measure asked students to estimate the average number of drinks they had consumed for each day of the week over the past 30 days.

Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989)

Negative consequences experienced as a result of alcohol consumption were assessed using the RAPI. The RAPI is a 23-item self-report measure that asks participants to indicate how many times they have experienced each of the specific alcohol-related problems over a specific period of time. For the purposes of this study, participants were asked to indicate the number of problems they experienced in the past 6 months. Responses are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (more than 10 times), and items are summed to create total scores. The RAPI has been shown to be a valid measure of alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., Martens, Neighbors, Dams-O’Connor, Lee, & Larimer, 2007; White & Labouvie, 1989) and has been used extensively with college students (e.g., Larimer et al., 2001; Marlatt et al., 1998). Martens, Neighbors, et al. (2007) used exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis to identify three distinct subscales on the measure, which they labeled Abuse/Dependence (12 items), Individual Consequences (7 items), and Social Consequences (4 items). The subscales accounted for 24%–76% of the variance in the individual items, with a mean variance accounted for of 53%. In the current study, these subscales were modeled as manifest indicators of a latent Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences variable. The internal consistency of the three subscales was .75, .81, and .83 for Social Consequences, Individual Consequences, and Abuse/Dependence, respectively.

Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale (Martens et al., 2005)

The PBS Scale is a 15-item measure that asks participants to indicate “the degree to which you engage in the following behaviors when using alcohol or ‘partying.’” Responses are scored using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (always), and items are summed to create subscale scores. The PBS Scale is comprised of three subscales: Stopping/Limiting Drinking (7 items, e.g., “Determine not to exceed a set number of drinks”), Manner of Drinking (5 items, e.g., “Avoid trying to ‘keep up’ or ‘out-drink’ others”), and Serious Harm Reduction (3 items, e.g., “Use a designated driver”). Support has been found for the construct validity of the PBS Scale, as scores on each of the subscales have been shown to be negatively correlated in the expected direction with both alcohol use and alcohol-related negative consequences, and the hypothesized factor structure has been supported across different groups of students (Martens et al., 2005; Martens, Pedersen, et al., 2007). In the current study, the three subscales were modeled as manifest indicators of a latent PBS variable. Coefficient alphas were .67, .77, and .87 for Serious Harm Reduction, Manner of Drinking, and Stopping/Limiting Drinking, respectively.

Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977)

Symptoms of depression were assessed using the CES-D. The CES-D is made up of four subscales totaling 20 items. Each of the four subscales measures a different dimension of depression: Depressed Affect (7 items), Positive Affect (4 items), Interpersonal Difficulties (2 items), and Neurovegetative/Somatic Symptoms (7 items). Participants are asked to report on a 4-point scale the frequency that each symptom had been experienced over the past week (0 = none of the time, 3 = all of the time), with higher scores indicating more frequent depressive symptoms (Positive Affect items are reverse scored and scores are summed for each subscale). Research has supported the psychometric properties of the CES-D (e.g., Rhee et al., 1999) and its use with college students (Radloff, 1991). In the current study, the four subscales were modeled as manifest indicators of a latent Depressive Symptoms variable. The internal consistency of the subscales ranged from .64 (Interpersonal Difficulties) to .86 (Depressed Affect). Although the CES-D asks about symptoms over a short timeframe (the past week), test–retest reliability of the measure across a variety of samples, including adolescents and college students, has yielded estimates ranging from .49–.61 over 1–4 month time frames (Devins, Orme, Costello, & Binik, 1988; Roberts, Andrews, Lewinsohn, & Hops, 1990; Wong, 2000). The scale is therefore a fairly stable measure of depressive symptoms.

Procedures

Students who committed an on-campus judicial infraction involving alcohol (e.g., having alcohol in a dorm room) were eligible to participate in this project. All students who committed such an infraction were mandated to attend some type of alcohol-intervention program. When meeting with their resident assistant regarding their violation, they were given the option of enrolling in this study and participating in one of the study interventions or completing an alternative intervention at the university counseling center. Participants who chose to enroll in the research project were scheduled for an individual meeting with a research assistant. Approximately 80% of the eligible students chose to enroll in the research study. During the enrollment meeting, participants signed a consent form in which they acknowledged that although they were required to complete some sort of intervention, participation in the research study was voluntary and all data they provided would be kept completely confidential. Participants were also informed that we had obtained a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health, which further protected the confidentiality of their data. During the meeting, participants completed an online questionnaire and were given a $25 gift card as compensation for their time. The measures included in this study were part of a larger baseline questionnaire participants completed. All data were collected before participants engaged in the mandated intervention. All of the procedures for the research project were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations among all measured variables are presented in Table 1. Significant associations existed between CES-D subscale scores and RAPI subscale scores but not between CES-D subscale scores and drinks per week. CES-D subscale scores were also associated with each PBS Scale subscale scores, and PBS Scale subscale scores were generally associated with RAPI subscale scores. Because of a lack of direct association between CES-D scores and drinks per week and no evidence that conditions existed for mediation without direct effects (Shrout & Bolger, 2002), we only examined a model that included alcohol-related negative consequences as the dependent variable.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations Among Study Variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies—Depression subscale | |||||||||||||

| 1. Depressed Affect | 2.71 | 3.56 | — | ||||||||||

| 2. Positive Affect | 2.79 | 2.71 | .46** | — | |||||||||

| 3. Neurovegetative/Somatic Symptoms | 4.24 | 3.42 | .69** | .32** | — | ||||||||

| 4. Interpersonal Difficulties | 0.56 | 1.02 | .53** | .34** | .47** | — | |||||||

| Protective Behavior Strategies Scale subscale | |||||||||||||

| 5. Stopping/Limiting Drinking | 19.54 | 8.09 | −.09* | −.08* | −.11* | −.02 | — | ||||||

| 6. Manner of Drinking | 15.86 | 5.31 | −.12* | −.09* | −.18** | −.07 | .68** | — | |||||

| 7. Serious Harm Reduction | 15.25 | 3.27 | −.11* | −.20** | −.09* | −.14** | .47** | .40** | — | ||||

| Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index subscale | |||||||||||||

| 8. Abuse/Dependence | 3.46 | 5.07 | .28** | .13** | .34** | .29** | −.11** | −.19** | −.25** | — | |||

| 9. Individual Consequences | 3.70 | 4.14 | .28** | .12** | .35** | .25** | −.28** | −.34** | −.27** | .67** | — | ||

| 10. Social Consequences | 2.31 | 2.38 | .21** | .11** | .25** | .22** | −.20** | −.25** | −.34** | .60** | .62** | — | |

| 11. Drinks per week | 18.24 | 15.26 | .01 | .01 | .07 | .05 | −.37** | −.38** | −.17** | .36** | .45** | .43** | — |

p < .05.

p < .01.

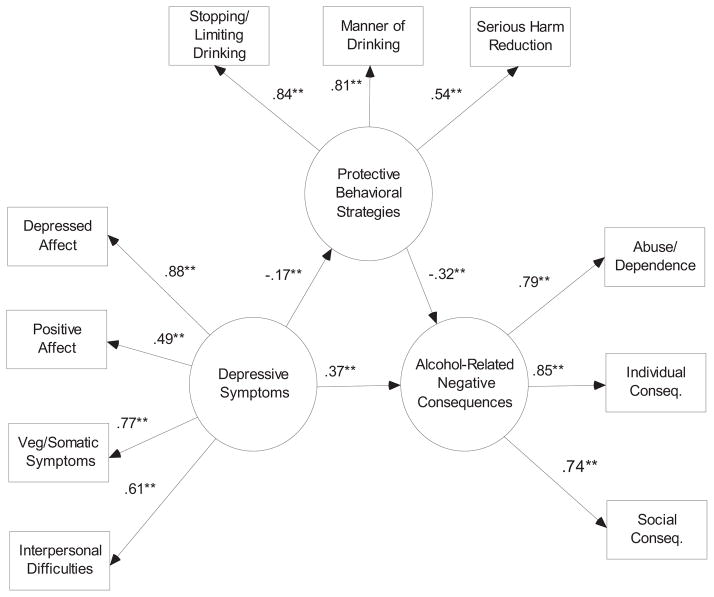

Mediation Tests

We used structural equation modeling to determine whether PBS mediates the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. All analyses were conducted with AMOS Version 7.0 (Arbuckle, 2006). We created a latent Depressive Symptoms variable with the four CES-D sub-scales as indicator variables, a latent PBS variable with the three PBS Scale subscales as indicator variables, and a latent Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences variable with the three RAPI subscales as indicator variables (see Figure 1). For identification purposes, the path between each latent variable and one of its indicators was fixed to 1, as were the parameters between the error and disturbance terms and their corresponding variables. Note that for appearance purposes the error and disturbance terms were not included in the figure. Maximum likelihood estimation procedures were used for all analyses. Results from preliminary testing indicated that the partially mediated model (i.e., the model with a direct path between Depressive Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences) fit better than the fully mediated model did (i.e., the model without this path), so the partially mediated model was used in bootstrapping tests of mediation. Bootstrapping procedures have been recommended as the preferred strategy for mediation tests as they compensate for problems associated with normal theory-based mediation analyses (Mallinckrodt, Abraham, Wei, & Russell, 2006; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). For the current study, we drew a random sample of 10,000 cases and used bias-corrected estimates and confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

Partially mediated model. Values represent standardized regression parameters. For appearance purposes, the error terms for the endogenous variables were not included. ** p < .01.

Results indicated a good overall fit to the hypothesized model. Although the chi-square test was statistically significant, χ2(32, N = 686) = 149.29, p < .001, other fit indices indicated a good model fit (e.g., comparative fit index = .95, incremental fit index = .95, standardized root-mean-square residual = .05; see Hu & Bentler, 1999). The standardized direct paths between Depressive Symptoms and PBS (β = −.17), PBS and Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences (β = −.32), and Depressive Symptoms and Alcohol-Related Negative Consequences (β = .37) were all statistically significant (p < .001). Finally, results from the bootstrapping analyses indicated that the 95% confidence interval for the estimate of the standardized indirect effect did not contain 0 (.02, .09). Thus, the indirect effect (β = .06) was statistically significant, indicating that use of PBS partially mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. Overall, the model accounted for 27.3% of the variance in RAPI scores and 3.0% of the variance in PBS Scale scores.

Discussion

The purpose of the present study was to determine whether the use of PBS mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. Consistent with prior studies among college students, we found that depressive symptoms were directly associated with alcohol-related negative consequences but not with alcohol use. We also found that PBS partially mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. These findings have several important implications for researchers and clinicians working in the area of college student substance use.

There are a number of potential reasons as to why use of PBS mediated the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. One possibility is that symptoms of depression make it difficult for individuals to activate and utilize PBS. PBS are by definition cognitive and behavioral in nature, and those high in depressive symptoms may not have the resources or motivation to activate these strategies. For example, a student high in depressive symptoms may not care about the negative consequences of his or her drinking, making him or her much less likely to engage in behaviors that would limit such consequences. Similarly, a depressed student may not have the cognitive resources to engage in the planning necessary to decide to limit one’s drinks, leave a social gathering at a specific time, or avoid certain types of drinking styles (e.g., shots of liquor).

Another possible explanation for the mediated effect is the fact that many of the PBS assessed in the current study are generally used in social situations. For example, items from the PBS Scale include having a friend let you know when you’ve had too much to drink and avoiding trying to keep up with others’ drinking rates. A student with high depressive symptoms may not be engaging socially and will therefore be less likely to utilize these strategies when drinking alcohol. Research has demonstrated an association between negative mood and drinking at home among college students, which may be likely to involve drinking alone (Mohr et al., 2005). On a related note, studies have shown an association between depressive symptoms and drinking to cope (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2003; Schuckit, Smith, & Chacko, 2006). Previous research has shown that use of PBS is associated with positively reinforcing drinking motives, like social motives, but not negatively reinforcing motives, such as coping (Martens, Ferrier, & Cimini, 2007). Thus, individuals with high depressive symptoms who are drinking to cope may not be motivated to use PBS, which in turn is related to a greater likelihood of experiencing alcohol-related negative consequences.

Although not a main focus of the current study, our results were consistent with prior studies that have shown that among college students depressive symptoms are associated with alcohol-related negative consequences but not alcohol use itself. One possible explanation for these somewhat counterintuitive findings could also involve the reasons why students higher in depressive symptoms use alcohol. Such students may be more likely to drink for negatively reinforcing reasons, like coping, which has been shown to have a strong relationship with alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g., Carey & Correia, 1997). Thus, although college students high in depressive symptoms may not drink more than other students do, when they do drink they may be more likely to experience negative consequences as a result of their consumption.

There are at least two clinical implications from this study for individuals working in the areas of prevention and treatment of alcohol-related negative consequences among college students. First, the results replicated previous findings regarding the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences. This suggests that clinicians should screen for and address excessive drinking among college students experiencing high levels of depressive symptoms in an attempt to prevent such students from experiencing alcohol-related negative consequences, such as unwanted or unplanned sex, physical illness, and personal injuries. Second, the results suggest that use of PBS may mitigate the relationship between depressive symptoms and alcohol-related negative consequences in this group. That is, perhaps teaching and encouraging college students with high depressive symptoms to utilize PBS will result in a decrease in alcohol-related negative consequences associated with drinking among this group. It is possible, as mentioned earlier, that one of the reasons depressed college students do not use PBS is that they may involve strategies that are not consistent with their current use of alcohol (e.g., strategies designed around social situations or drinking with friends). But, many of the strategies may be applicable to any college student drinker, such as avoiding different types of alcohol, drinking slowly, and determining in advance not to exceed a set number of drinks. It may be more difficult to encourage a depressed student to use these strategies, but cognitive-behavioral drinking control strategies are common components of empirically supported alcohol prevention interventions (e.g., the Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students program, Dimeff et al., 1999).

There were limitations to this study that should be noted. The sample was primarily White, so the generalizability of the findings to students of color is not known. Additionally, participants were undergraduate students who had experienced an alcohol-related campus judicial infraction, which also limits the generalizability of the findings. One can argue, though, that it may be particularly important to study patterns of relationships among alcohol-related variables in such “high-risk” samples. All data were self-report, although studies have generally shown that self-report data regarding alcohol use are reliable and valid (e.g., Babor, Steinberg, Anton, & del Boca, 2000), and participants were ensured that their responses would be confidential. Third, the data were cross-sectional in nature, limiting any causal conclusions regarding the nature of the mediated effects. Finally, we should note that although statistically significant, the size of the mediated effect in this study was relatively small. Despite these limitations, this study makes an important contribution to the literature on the prevention of college student alcohol use. We encourage future researchers to build upon these findings, especially in terms of testing longitudinal designs and more complex models. We also encourage researchers to design intervention studies to test the specific treatment effects associated with PBS.

Acknowledgments

The project was in part supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Grant U18 AA 015039-01A1. A previous version of this article was presented at the 2008 International Counseling Psychology Conference, Chicago, IL.

Contributor Information

Matthew P. Martens, University of Memphis

Jessica L. Martin, University at Albany—State University of New York

E. Suzanne Hatchett, University of Memphis.

Roneferiti M. Fowler, University of Memphis

Kristie M. Fleming, University of Memphis

Michael A. Karakashian, University of Memphis

M. Dolores Cimini, University at Albany—State University of New York.

References

- Arbuckle JL. AMOS 7.0 user’s guide. Chicago: SPSS; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Steinberg K, Anton R, del Boca FK. Talk is cheap: Measuring drinking outcomes in clinical trials. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61:55–63. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Benton SL, Schmidt JL, Newton FB, Shin K, Benton SA, Newton DW. College student protective strategies and drinking consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:115–121. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camatta CD, Nagoshi CT. Stress, depression, irrational beliefs, and alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1995;19:142–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01482.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delva J, Smith MP, Howell RL, Harrison DF, Wilke D, Jackson DL. A study of the relationship between protective behaviors and drinking consequences among undergraduate college students. Journal of American College Health. 2004;53:19–26. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.1.19-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devins GM, Orme CM, Costello CG, Binik YM. Measuring depressive symptoms in illness populations: Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Psychology and Health. 1988;2:139–156. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA. Brief alcohol screening and intervention for college students: A harm reduction approach. New York: Guilford; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit AR, Crum RM. Prospective study of depression and the risk of heavy alcohol use in women. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:751–758. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P, Ergis A, Allilaire J. Problem solving abilities in unipolar depressed patients: Comparison of performance on the modified version of the Wisconsin and California sorting tests. Psychiatry Research. 2002;104:145–156. doi: 10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisner IM, Larimer ME, Neighbors C. The relationship among alcohol use, related problems, and symptoms of psychological distress: Gender as a moderator in a college sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, et al. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24: Changes from 1998–2001. Annual Review of Public Health. 2005;26:259–279. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope and alcohol use and abuse in unipolar depression: A 10-year model. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:159–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kyte ZA, Goodyear IM, Sahakian BJ. Selected executive skills in adolescents with recent first major episode depression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2005;46:995–1005. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, Cronce JM. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62:370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallinckrodt B, Abraham WT, Wei M, Russell DW. Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:372–378. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Do protective behavioral strategies mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use in college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:106–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66:698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Dams-O’Connor K, Lee CM, Larimer ME. The factor structure of a dichotomously scored Rutgers Alcohol Problems Index. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:597–606. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW, Ferrier AG, Cimini MD. Measuring alcohol-related protective behavioral strategies among college students: Further examination of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:307–315. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Taylor KK, Damann KM, Page JC, Mowry ES, Cimini MD. Protective factors when drinking alcohol and their relationship to negative alcohol-related consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2004;18:390–393. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.18.4.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, et al. Moving beyond the keg party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagoshi CT. Perceived control of drinking and other predictors of alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Addiction Research. 1999;7:291–306. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patock-Peckham JA, Hutchinson GT, Cheong J, Nagoshi CT. Effect of religion and religiosity on alcohol use in a college student sample. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1998;49:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhee SH, Petroski GF, Parker JC, Smarr KL, Wright GE, Multon KD, et al. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale in rheumatoid arthritis patients: Additional evidence for a four-factor model. Arthritis Care and Research. 1999;12:392–400. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199912)12:6<392::aid-art7>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Andrews JA, Lewinsohn P, Hops H. Assessment of depression in adolescents using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale. Psychological Assessment. 1990;2:122–128. [Google Scholar]

- Schuckit MA, Smith TL, Chacko Y. Evaluation of a depression-related model of alcohol problems in 430 probands from the San Diego prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2006;82:194–203. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and non-experimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:422–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50:203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong YI. Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale in a homeless population. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:69–76. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]