To the Editor,

Percutaneous transthoracic computed tomography (CT)-guided needle biopsy is a well-established, simple, reliable diagnostic interventional procedure for definitive pathologic diagnosis of thoracic neoplasms because of its high diagnostic yield and relatively low morbidity [1]. However, one of the most serious complications of CT-guided biopsy, although extremely rare, is implantation of carcinoma along the biopsy route.

Parvimonas micra (formerly known as Peptostreptococcus micros) is a nonspore-forming anaerobic gram-positive coccus widely distributed as commensal flora in the oral cavity that, under immunosuppressed or traumatic conditions, can become pathogenic and cause brain, liver, and thoracic infections, as well as generalized necrotizing soft tissue infections. Within the thorax, P. micra may cause aspiration pneumonia, lung abscesses, empyema, and mediastinitis. Rarely, P. micra infections can also occur in patients with no recognized predisposing conditions [2].

We present a case of a patient suspected to have lung cancer who underwent two CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsies and developed a chest wall mass 10 days after the second percutaneous biopsy. This mass was ultimately confirmed to be a P. micra chest wall abscess.

A 67-year-old male ex-smoker with cough and constitutional syndrome (loss of appetite, fatigue, and progressive weight loss over 6 weeks) and no fever was referred to our institution after chest radiographs revealed a nonresolving opacity in the right lung base. His medical history was otherwise nonsignificant. Physical examination showed decreased breath sounds on auscultation at the right hemithorax. The patient had been treated with levofloxacin (500 mg/12 hours) for 7 days, but was not taking corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants. Tests for human immunodeficiency, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C viruses were negative. Thoracic CT showed a heterogeneous consolidation in the right lung involving both the right upper lobe and the right middle lobe (Fig. 1). Large mediastinal adenopathies were also present. Lung carcinoma was suspected, but two bronchoscopic transbronchial biopsies failed to identify cancerous cells, so a CT-guided biopsy of the right lung lesion was performed.

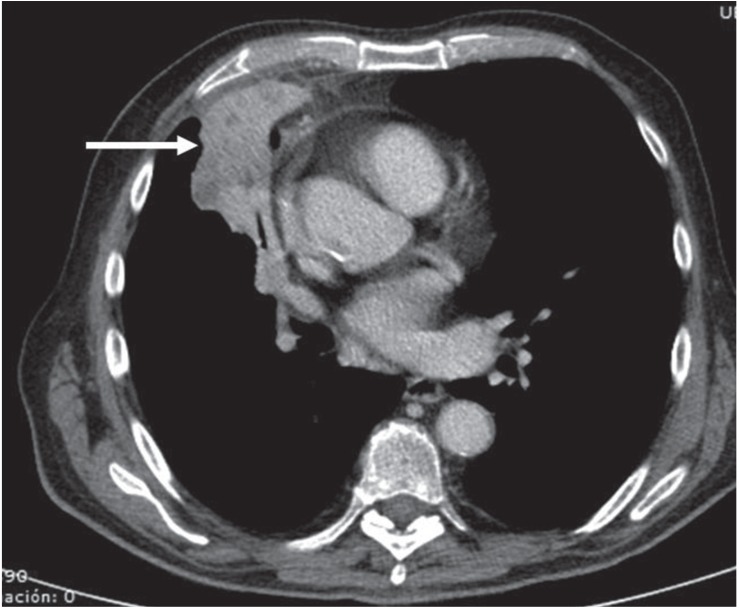

Figure 1.

Axial contrast-enhanced computed tomography image of the thorax (mediastinal window) shows a heterogenous consolidation (arrow) involving both the right upper lobe and the right middle lobe.

The patient was placed in the supine position on the CT table and an 18 G semi-automated coaxial core biopsy needle (Bard Magnum, Bard, Tempe, AZ, USA) was inserted into the patient's thorax through the right pectoral muscle (Fig. 2). Pathologic analysis of the obtained specimens also failed to reveal cancerous cells. The right lung opacity was punctured again 5 days later with the same coaxial system. Surprisingly, pathologic analysis was again nondiagnostic and only showed lymphocyte-rich inflammatory changes and nonspecific areas of organizing pneumonia. No immediate complications (i.e., pneumothorax or hemorrhage) were observed during these percutaneous procedures.

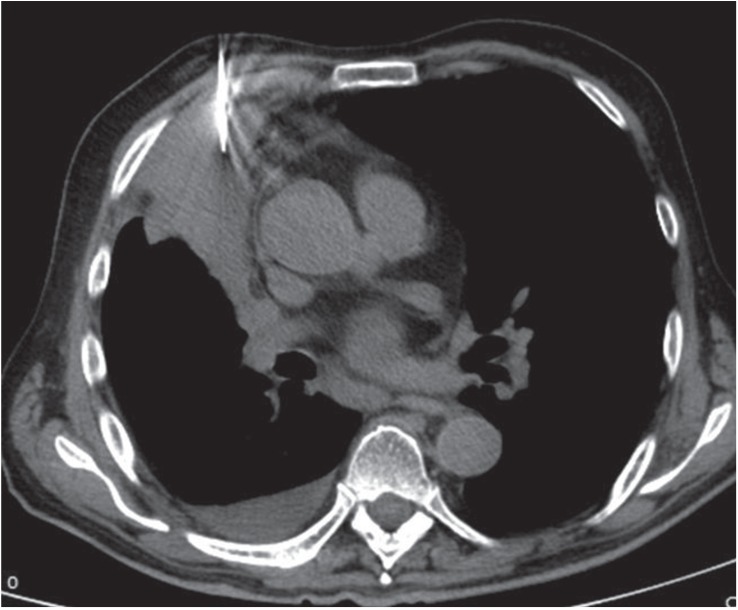

Figure 2.

Axial nonenhanced computed tomography image of the thorax (mediastinal window) shows an 18 gauge semi-automated coaxial core biopsy needle traversing the right anterior chest wall into the pulmonary consolidation.

Ten days after the second transthoracic biopsy, the patient developed a painful mass on the right anterior chest wall. Since this mass was on the puncture site of the previous biopsy, needle track dissemination of carcinoma was suspected. A new thoracic CT revealed a low density well-defined lesion in the right pectoral muscle (Fig. 3). This lesion was punctured and pus was aspirated. Microbiological culture of the aspirated pus identified clindamycin-susceptible P. micra.

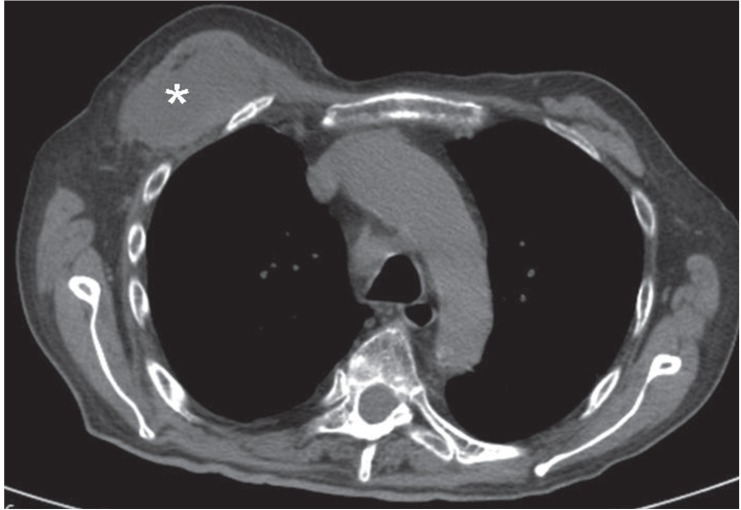

Figure 3.

Axial nonenhanced computed tomography image of the thorax (mediastinal window) shows a low-attenuation mass (asterisk) in the right pectoral muscle.

The patient was started on clindamycin (600 mg/8 hours intravenous) and the anterior chest wall abscess was drained. After 8 weeks of treatment, the right lung consolidation had decreased in size, the chest wall abscess had resolved, and the patient's symptoms had improved. The patient's mouth was explored and was found to have suboptimal oral hygiene and periodontal disease. We believe that the lung consolidation was also caused by P. micra infection and that dissemination to the chest wall was a complication of percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy.

Percutaneous transthoracic CT-guided needle biopsy is a well-established, simple, reliable diagnostic interventional procedure for definitive pathologic diagnosis of thoracic neoplasms since it has a high diagnostic yield and a relatively low morbidity [1]. However, immediate and delayed complications may occur. Among the common immediate complications are pneumothorax, hemoptysis/pulmonary haemorrhage, and hemothorax. Most of these complications are managed conservatively, although pneumothorax may require tube drainage. Air embolism is the most serious immediate complication and has a high mortality rate, although it is very rare. Delayed complications include infection and dissemination of cancer cells along the biopsy track. The latter complication is also exceedingly rare, with a reported frequency less than 0.04%, but the consequences can be devastating [3].

Factors involved in the likelihood of dissemination include thickness of the biopsy needle, number of punctures, distance between the tumor and chest wall, operator skill, tumor growth rate, and the patient's immune status [4]. Dissemination risk is also minimized by a coaxial technique that prevents contact between the biopsy needle and the chest wall.

In our case, an 18-gauge semi-automated biopsy needle was used twice (5 days apart). Dissemination occurred despite our use of a coaxial technique, which may be explained in our patient by the extensive contact of the lung consolidation with the anterior pleural surface of the right hemithorax, which could allow and facilitate direct dissemination of the infected tissue from the peripheral lung parenchyma to the chest wall through the small pleural defect created by the outer needle of the coaxial system. Since the pleural surface was punctured twice, this may have also increased the probability of chest pleural dissemination in our immunocompetent patient.

P. micra is a nonspore-forming anaerobic gram-positive coccus widely distributed as normal flora in the oral mucosa. Predisposing conditions for this infection include immunodeficiency, diabetes, steroid treatment, previous surgery, and neoplasia. In these conditions, this bacteria can cause opportunistic infections in the central nervous system, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis, as well as generalized necrotizing soft tissue infections. Opportunistic infections caused by P. micra more commonly cause brain abscesses and endocarditis following dental manipulations. Within the thorax, P. micra can cause aspiration pneumonia, lung abscesses, empyema, and mediastinitis. Rarely, P. micra infections can also occur in patients with no recognized predisposing factors. According to various practice guidelines, such as those of the Infectious Diseases Society of America, anaerobic infections should be treated with either clindamycin or a combination of penicillin and a β-lactamase inhibitor for 2 to 4 weeks depending on response. In the case of an associated lung abscess, treatment is recommended for up to 3 months or until the chest radiograph clears, though treatment can be shortened with proper surgical drainage, as in our case [2].

The imaging findings of anerobic thoracic infections are not specific and may sometimes resemble lung carcinoma, as in our case. Common CT findings include lung consolidation, necrotic nodules and masses, and cavitation [5]. The chest wall is involved in a small number of patients. To the best of our knowledge, there are no previous reports describing chest wall dissemination of P. micra pulmonary infection following transthoracic lung biopsy.

In conclusion, we present the case of an immunocompetent patient who underwent two nondiagnostic transbronchial and CT-guided transthoracic needle biopsies due to suspicion of lung cancer. Ten days after the second percutaneous biopsy, the patient developed a chest wall mass that was ultimately confirmed to be a P. micra chest wall abscess.

KEY MESSAGE

Percutaneous lung biopsy

Computed tomography

Chest wall infection

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Wu CC, Maher MM, Shepard JA. CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy of the chest: preprocedural evaluation and technique. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W511–W514. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy EC, Frick IM. Gram-positive anaerobic cocci: commensals and opportunistic pathogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:520–553. doi: 10.1111/1574-6976.12005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu CC, Maher MM, Shepard JA. Complications of CT-guided percutaneous needle biopsy of the chest: prevention and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W678–W682. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimamoto H, Inaba Y, Yamaura H, et al. Chest wall dissemination of nocardiosis after percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:797–799. doi: 10.1007/s00270-007-9002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim TS, Han J, Koh WJ, et al. Thoracic actinomycosis: CT features with histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:225–231. doi: 10.2214/AJR.04.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]