Dear Editor,

Dominant deafness-onychodystrophy syndrome (DDOD syndrome; MIM 124480) is characterized mainly by congenital sensorineural hearing loss accompanied by dystrophic or absent nails. Prominent differences between DDOD syndrome and DOORS syndrome (deafness, onychodystrophy, osteodystrophy, mental retardation and seizures; MIM 220500) are the intellectual disability and seizure aspects of DOORS1. TBC1D24 mutations were recently identified as a cause of DOORS syndrome2. To date, six families with DDOD syndrome in various ethnic populations have been reported3. However, the molecular etiology of DDOD remains unknown.

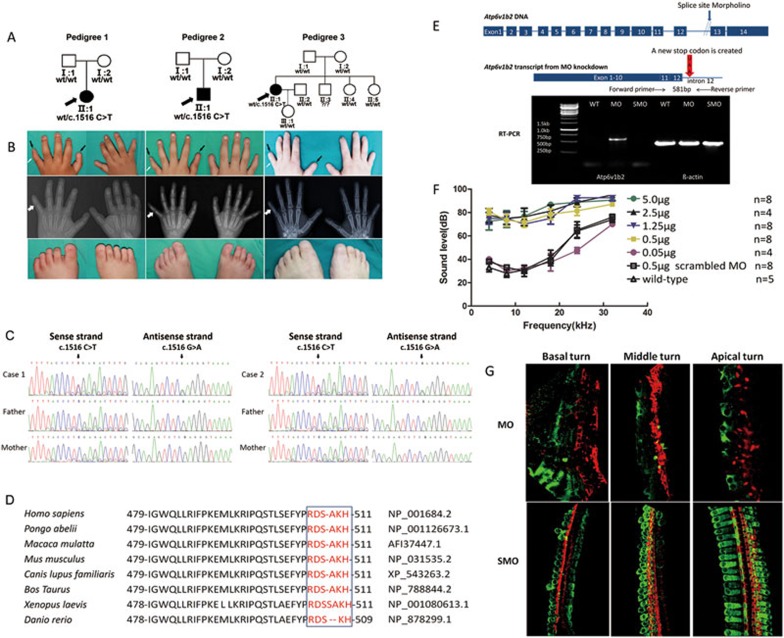

We collected three Chinese DDOD pedigrees during the past two years. The probands displayed identical phenotypes including severe congenital sensorineural hearing loss, absence of nails and aplasia of the middle phalanx in the fifth fingers (Figure 1A and 1B). None showed inner ear malformation and intellectual disability. All three individuals had unilateral cochlea implantation at the ages of 2.5, 2 and 18 years, respectively. The successful language rehabilitation in the DDOD probands further confirmed their normal mental development.

Figure 1.

Phenotype and mutation analysis of ATP6V1B2 in DDOD probands and Atp6v1b2-knockdown analysis in the mouse cochlea. (A) Pedigree of three DDOD families and segregation of the c.1516 C>T mutation. (B) Phenotype of onychodystrophy in 3 DDOD pedigrees. Pictures of the hands on the first line show the absence of the fifth finger and thumb nails indicated by black arrows, aplasia of the middle phalanx in the fifth fingers indicated by white arrows, as well as onychodystrophy-like malacia and pitting of the middle three fingernails. The second line, X-ray of the hands shows aplasia of the middle phalanx in the fifth fingers indicated by white arrows. Pictures of the feet on the third line show the absence of all toenails. (C) Partial sequences of exon 14 in ATP6V1B2 from normal-hearing parents and affected DDOD probands 1 and 2, respectively, showing the c.1516 C>T (p.Arg506X) nonsense mutation. (D) Conservation analysis shows that the last six amino acids, p.Arg506, p.Asp507, p.Ser508, p.Ala509, p.Lys510 and p.His511 in ATP6V1B2 are conserved across human, pongo, macaca, mouse, canis, bos taurus, Xenopus and danio. There is a slight exception that Ala509 is missing in the danio sequence and an additional serine residue is inserted in Xenopus sequence. (E) RT-PCR analysis shows intron 12 retention in the Atp6v1b2 transcript of cochlea-specific Atp6v1b2-knockdown mice. The MO was designed to anneal at the junction of intron 12 and exon 13, which resulted in a partial inclusion of intron 12 followed by a stop codon UAA (indicated by the red arrow). The forward RT-PCR primer was in exon 11 and the reverse primer was in intron 12. The RNA was extracted 3 days after MO (0.5 μg/μl) inner ear injection. Since the reverse primer corresponded to intron 12 sequences, no bands were observed in WT or SMO-injected mice. The primer pairs amplified a product of 581 bp, including part of exon 11, exon 12 and part of intron 12 in the presence of abnormal splicing due to the Atp6v1b2-specific MO injection. (F) Hearing thresholds (y-axis) were determined based on ABR measurements at various frequencies (x-axis) for cochlea-specific Atp6v1b2-knockdown mice, SMO-injected control mice and WT mice. ABR thresholds were measured on postnatal day 30 (P30), 4 weeks after cochlea injection. Legends for different mouse groups are shown in the panel, n = the number of ears. Vertical bars represent standard errors of the mean. (G) Flattened whole mount cochlea staining shows the degeneration of hair cells in the Atp6v1b2-knockdown mice. Twenty-one days after cochlea injection with Atp6v1b2-specific MO (0.5 μg/μl), the majority of hair cells in the basal, middle, and apical turns died. Twenty-one days after cochlea injection with SMO (0.5 μg/μl), the hair cells in the basal, middle and apical turns remained normal. Green: Atp6v1b2; red: Phalloidin.

Whole-exome sequencing was performed in pedigrees 1 and 2, including the probands and their parents (BGI-Shenzhen, China). In each sample, we obtained approximately 5.9-6.9 Gb of data. The data mapped to the targeted region have a mean depth of 145.74 folds, and 99.41% of the targeted bases were covered. For bioinformatics analysis, we focused on variants in coding regions. Variants were filtered by four databases, the 1000 Genomes Project, the HapMap database, the EVS database, and an in-house database from BGI, with the Minor Allele Frequency lower than 0.005. Based on 1) the dominant inheritance of DDOD, 2) the identical phenotype of the two probands, and 3) the pedigree traits (only one individual and neither parent had symptoms), we assumed that there may be a de novo mutation following the dominant inheritance characteristics. After completing such a filtering process, 6 genes with variants shared by the two probands were identified (Supplementary information, Table S1). The 14 variants in the 6 shared genes (CIB1, MUC4, OR5H6, PRAMEF1, AMBN and ATP6V1B2) were then tested by Sanger sequencing. Combining the sequencing results, the prediction results by SIFT, Polyphen, Mutationtaster and the genes' pathway, and their expression in human fetal cochlear EST database, ATP6V1B2 was identified as one potential gene that associates with DDOD. An identical heterozygous de novo c.1516 C>T (p.Arg506X) mutation in ATP6V1B2 was verified in two probands (Figure 1C). The result was further confirmed by Sanger sequencing in another DDOD family (pedigree 3) (data not shown). We then used a restriction enzyme assay to perform a molecular epidemiology analysis of the mutation in 1 053 ethnically matched normal controls. The mutation was not detected in the normal-hearing population (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Although de novo mutations have recently been shown to play a major role in human diseases with intellectual disability such as Dravet's syndrome, Kabuki syndrome and Schinzel-Giedion syndrome4,5,6,7,8, the identication of a same de novo mutation in 3 unrelated DDOD individuals is extremely rare.

The p.Arg506X mutation in ATP6V1B2 inserts a premature stop codon and results in a truncated protein. Conservation analysis of amino acids in 8 ATP6V1B2 orthologs indicates that the last six amino acids, from residues 506 to 511, are highly conserved (Figure 1D). Three-dimensional protein structure modeling suggests that the p.Arg506X mutation results in failure of hydrogen bond formation between Tyr504 and Asp507 in ATP6V1B2 (Supplementary information, Figure S1B). Expression analysis performed by quantitative real-time PCR on total RNA isolated from leukocytes in pedigree 3 showed that the average expression level of ATP6V1B2 in case 3 was comparable to that in her parent controls, indicating that the mutant ATP6V1B2 mRNA is stable. The identification of ATP6V1B2 c.1516 C>T mutation in three independently identified DDOD patients provides evidence that defect in ATP6V1B2 is the genetic etiology for DDOD syndrome.

ATP6V1B2 encodes a component of the vacuolar ATPase (V-ATPase), which is a multisubunit enzyme mediating acidification of eukaryotic intracellular organelles. V-ATPase is composed of a cytosolic V1 domain responsible for ATP hydrolysis and a transmembrane V0 domain responsible for protein translocation. ATP6V1B2 is one of the two V1 domain B subunit isoforms, and as it is highly expressed in the organ of cerebrum and in the organelle of lysosome, it is usually called a brain isoform or lysosomal V1 subunit B2. Deficiencies of ATP6V1B1 and ATPV0A4 are related to distal renal tubular acidosis and hearing loss9. To the best of our knowledge, no report has linked the function of ATP6V1B2 to hearing. The gene related to DOORS syndrome, TBC1D242, encodes a member of the Tre2-Bub2-Cdc16 (TBC) domain-containing Rab (Ras-related proteins in brain)-specific GTPase-activating proteins, which coordinate Rab proteins and other GTPases for the regulation of membrane trafficking. TBC1D24 and ATP6V1B2 are all known to be widely expressed, most highly in the brain and kidneys. Immunostaining of mouse cochlear sections and cultured cochlear tissues showed Atp6v1b2 expression mainly in the organ of Corti and spiral ganglion neurons (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). This expression pattern was found in both the early postnatal (postnatal day 2, P2) and the adult (P30) cochlea. Tbc1d24 expresses in the stereocilia of hair cells as well as in spiral ganglion neurons10. The identical distribution regions of TBC1D24 and ATP6V1B2 and their function with GTPases or ATPases activity indicate that they may have some physiological link.

To investigate the function of ATP6V1B2 in the cochlea, we generated a cochlea-specific Atp6v1b2-knockdown mouse model using morpholino oligomer (MO) (Supplementary information, Data S1). The oligomer was designed to anneal at the junction of intron 12 and exon 13, which resulted in a partial inclusion of intron 12 followed by a stop codon that excluded the expression of exons 13 and 14 in the mRNA (Figure 1E). The Atp6v1b2 MO was microinjected (0.05-5.0 μg/μl) into the scala media of the basal turn of the mouse cochlea before postnatal day 3. Hearing sensitivity has been shown to be unaffected by such an injection procedure11. RT-PCR was used to verify the abnormal transcript product containing part of intron 12 in the mouse cochlea 3 days after injection (Figure 1E). Four weeks post-injection, auditory brainstem response (ABR) tests showed that hearing thresholds in the mice injected with the MO at the concentration of 0.5, 1.25, 2.5 and 5.0 μg/μl were elevated by 30-50 dB compared to wild-type (WT) mice (Figure 1F). However, hearing thresholds in mice injected with 0.05 μg/μl of MO was within the normal range, indicating the dosage-dependence of the hearing loss phenotype. All the mice receiving scrambled MO injection (0.5 μg/μl) displayed normal hearing (Figure 1F). Immunological staining revealed that Atp6v1b2 expression was knocked down significantly in the whole cochlea, especially in hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons (Figure 1G). Western blot analysis showed that 7 days after injection, the level of Atp6v1b2 was decreased distinctly in spiral ganglia neurons and slightly in the organ of Corti, whereas 21 days after injection, the Atp6v1b2 level was significantly decreased in the organ of Corti (Supplementary information, Figure S1D).

To evaluate the pathogenicity of the ATP6V1B2 c.1516 C>T mutation, we transfected the pIRES2-EGFP-ATP6V1B2 WT and pIRES2-EGFP-ATP6V1B2 c.1516 C>T mutant plasmids into HEK293 cells. We found that the ATPase hydrolysis activity significantly decreased in the transfected cells when the ratio of the mutant/WT increased. This trend indicates that the c.1516 C>T mutant reduced ATPase hydrolysis activity compared with the WT. The proton transport activity of V-ATPase in lysosomes was measured using a lysosome-specific dye. A statistically significant difference in lysosomal pH was detected between ATP6V1B2 WT- and c.1516 C>T mutant-transfected cells (LSD test, p = 0.02, Supplementary information, Figure S1E), indicating the reduced acidification caused by c.1516 C>T mutation. Taken together, these results suggest that ATP6V1B2 c.1516 C>T mutation is a haploinsufficient mutation.

In summary, we identified a de novo mutation (c.1516 C>T (p.Arg506X)) in ATP6V1B2 as the cause of DDOD syndrome in three independently identified individuals using whole-exome sequencing. Molecular epidemiology analysis showed that the mutation was not present in 1 053 ethnically matched normal hearing controls. We generated a cochlea-specific Atp6v1b2-knockdown mouse model and found that Atp6v1b2 deficiency leads to severe sensorineural hearing loss. In vitro pathogenic evaluation showed that the ATP6V1B2 p.Arg506X is a haploinsufficient mutation and resulted in abnormal acidification in lysosomes. These findings provide the molecular basis for DDOD genetic diagnosis as well as future therapeutic interventions.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank Yueshuai Song in Chinese PLA General Hospital for technical assistance with figure preparation and graphical artwork. We sincerely thank Yuanyuan Cui in Emory University for her kindly and timely guidance with cell culture and RT-PCR. The work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2012BAI09B02 to PD), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81230020 to PD and 81371098 to YYY), the US National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders (NIDCD R01DC010204, RO1 DC006483 and 4R33DC010476 to XL), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7132177 to YYY), and the Beijing Nova program (2009B34 to YYY)

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Information

ATP6V1B2 c.1516 C>T mutation analysis and Atp6v1b2 expression analysis in mouse cochlea.

Filtering of SNP variants obtained in whole exome NGS

Materials and Methods

References

- James AW, Miranda SG, Culver K, et al. Am J Med Genet A. 2007. pp. 2821–2831. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Campeau PM, Kasperaviciute D, Lu JT, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2014. pp. 44–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- White SM, Fahey M. Am J Med Genet A. 2011. pp. 2512–2515. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vissers LE, de Ligt J, Gilissen C, et al. Nat Genet. 2010. pp. 1109–1112. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Vadlamudi L, Dibbens LM, Lawrence KM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2010. pp. 1335–1340. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ng SB, Bigham AW, Buckingham KJ, et al. Nat Genet. 2010. pp. 790–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hoischen A, van Bon BW, Gilissen C, et al. Nat Genet. 2010. pp. 483–485. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hamdan FF, Gauthier J, Spiegelman D, et al. N Engl J Med. 2009. pp. 599–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stover EH, Borthwick KJ, Bavalia C, et al. J Med Genet. 2002. pp. 796–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Hu L, Chai Y, et al. Hum Mutat 2014. Apr 11. doi:: 10.1002/humu.22558 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang Y, Sun Y, Chang Q, et al. J Gene Med. 2013. pp. 123–133. [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

ATP6V1B2 c.1516 C>T mutation analysis and Atp6v1b2 expression analysis in mouse cochlea.

Filtering of SNP variants obtained in whole exome NGS

Materials and Methods