Abstract

A new class of synthetic hallucinogens called NBOMe has emerged, and reports of adverse effects are beginning to appear. We report on a case of a suicide attempt after LSD ingestion which was analytically determined to be 25I-NBOMe instead. Clinicians need to have a high index of suspicion for possible NBOMe ingestion in patients reporting the recent use of LSD or other hallucinogens.

Keywords: LSD, Hallucinogens, Psychedelics, NBOMe

Introduction

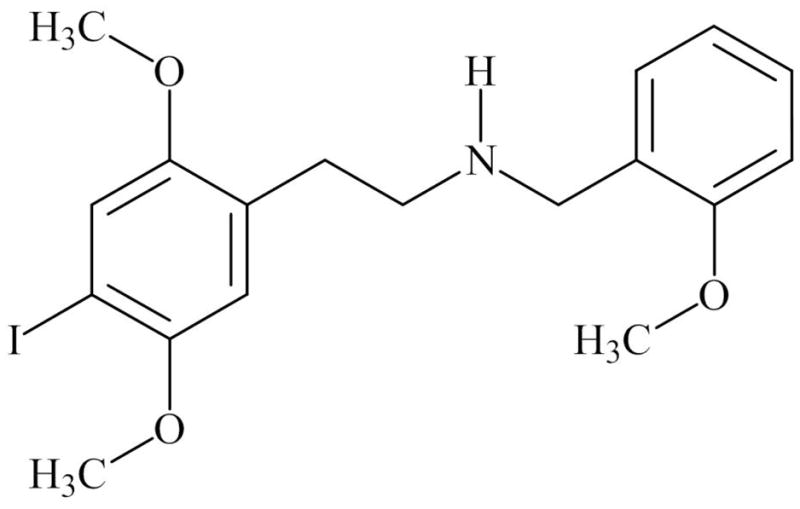

Since 2010, a novel class of synthetic hallucinogen called NBOMe has become available on the internet, most commonly as 4-iodo-2,5-dimethoxy-N-(2-methoxybenzyl)-phenylethylamine (Figure 1) or simply as 25I-NBOMe (Lawn et al. 2014; Ninnemann and Stuart 2013; Caldicott, Bright, and Barratt 2013). Very few pharmacologic studies have been conducted on these drugs (Halberstadt and Geyer 2014), but reports of adverse effects from human NBOMe ingestion began to appear in the scientific literature in 2013 (Hill et al. 2013; Poklis et al. 2014; Rose, Poklis, and Poklis 2013; Walterscheid et al. 2014; Stellpflug et al. 2013). In all cases so far reported, the patient or the bystanders reported the ingestion of either NBOMe or 2C-I, facilitating the identification of the substance. In contrast, here we report on a case of a suicide attempt after ingesting what the patient thought was lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD).

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of 25I-NBOMe

Case Report

Mr. B is an 18 year old male who was brought to the emergency room after calling 911 to report he had tried to kill himself following the ingestion of “2 hits of acid”. Mr. B, a college freshman, reported no prior medical history, psychiatric diagnosis, suicidal ideation or attempts, self-injurious behaviors, psychiatric hospitalizations, psychiatric medication use, or treatment by a mental health professional. Mr. B noted a 3–4 month history of mild depression in the context of stressors at school, but denied any prior suicidal ideation or perceptual disturbances. He drank alcohol infrequently but smoked marijuana regularly. He denied any other drug use including hallucinogens, except for having tried salvia divinorum once in high school. Mr. B had an interest in trying LSD, and approached a friend who claimed to have “good LSD.” The night prior to his presentation to the emergency room, Mr. B obtained 2 “blotters” of approximately ¼-inch size and placed them under his tongue. He recalled the taste to be moderately bitter. Mr B’s mental state at the time of ingestion was described as calm and mildly anxious. He had no significant expectations about LSD intoxication other than that it may help him experience interesting sensations. Mr B ingested the drug in his friend’s dorm room in the presence of several friends, none of whom were going to ingest the substance. After approximately one hour, he began to experience euphoria, tachycardia, and visual hallucinations. The drug effects continued to increase in intensity over the next several hours, and he became increasingly anxious and confused. At this point Mr B retreated to his own dorm room, and was alone for the remainder of the night. Mr. B experienced repetitive thoughts that he was “trapped” which further worsened his anxiety and he began to panic. When these feelings did not subside, he began to contemplate suicide as a way to end the experience. He then proceeded to use a pair of scissors to stab himself in the neck and chest. He was unable to remember the events that followed, and suspects he may have lost consciousness. Approximately 11 hours after initially ingesting LSD, he realized the extent of his injuries and called 911.

On arrival in the emergency room, Mr. B was noted to be alert and oriented, anxious and in moderate distress, and reported he was no longer under the influence of LSD. He was afebrile, and had a heart rate of 90bpm, blood pressure of 140/84mmHg, respirations of 20/minute, and oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. On exam, his pupils were mildly dilated at 5mm, and the following injuries were noted—a 12cm gaping wound in the anterior neck visible to the thyroid cartilage and trachea, two 8cm wounds to the right lateral neck not penetrating fascia, and a 2cm left anterior chest wall penetrating stab wound that extends beyond the fascia. Laboratory studies were within normal limits, and the routine toxicological screen of urine was positive only for marijuana metabolites. Imaging studies showed moderately sized left pneumothorax causing a shift of the mediastinum, a small left pleural effusion, and patchy opacities in the left base. A chest tube was placed, and Mr. B was sent to the operating room for wound exploration, bronchoscopy, endoscopy, washout, and closure.

During the hospitalization, Mr. B reported feeling depressed given the severity of his injuries, but denied any ongoing suicidal ideation. No symptoms of psychosis or mania were noted. Mr. B provided consent to having his blood sample sent for analysis for NBOMes. On hospital day 3, he was transferred to a psychiatric facility for continued treatment. He was discharged home one week later to outpatient psychiatric follow-up. Two weeks after the incident, he was evaluated at the surgery clinic where his wounds were noted to be healing well. No further psychiatric complications were reported by the patient.

A serum sample obtained at the time of admission to the emergency room was sent for testing which applied a deuterated internal standard modification of a previously described method (Poklis et al. 2013). Analysis indicated the presence of 25I-NBOMe at a concentration of 34pcg/ml.

Discussion

This case represents the first report of an LSD ingestion that was analytically confirmed to be 25I-NBOMe instead. NBOMes are N-methoxy-benzyl substituted 2C class of hallucinogens, initially synthesized for research purposes as a potent 5HT2A receptor agonists (Braden et al. 2006). The 2C hallucinogens (i.e. 2C-I, 2C-B, etc) are phenylethylamines with methoxy substitutions at the 2- and 5- positions, structurally related to mescaline, producing psychological and somatic effects common to hallucinogens that are 5-HT2A receptor agonists. However, compared to previous 2C compounds, NBOMes have a significantly higher affinity at the 5-HT2A receptor (Halberstadt and Geyer 2014). As a consequence, sublingual doses as low as 100μg may produce threshold effects (Zuba, Sekuła, and Buczek 2013). Drug effects are likely to be similar to the 2C hallucinogens and LSD, including powerful visual and sensory effects, alterations in cognition and affect, and mystical experiences (Erowid and Erowid 2013).

Currently, the most widely used NBOMe derivative appears to be 25I-NBOMe (iodine substitution), followed by 25B-NBOMe (bromine substitution) and 25C-NBOMe (chlorine substitution) (Lawn et al. 2014). They are typically sold on blotter paper but may also appear as powder, with names such as “N-Bomb” and “Smiles”(Erowid and Erowid 2013). Historically, LSD has been distributed on blotter paper with colorful and/or unique artwork which may serve as a trademark in the illicit drug trade. NBOMe blotter paper is similarly marked with identifying artwork. Due to the declining availability of LSD in recent years, NBOMes are reportedly being sold as LSD not only because they produce similar effects but also because of the potency which permits NBOMes to be taken as blotters (Erowid and Erowid 2013).

The emergence of NBOMes as an LSD substitute raises significant public health concerns. Adverse reactions to LSD and other classical hallucinogens are typically time-limited in nature. Most common adverse reaction is an acute episode of anxiety or panic (“bad trip”) that resolves with reassurance and the use of benzodiazepines. Even though prolonged psychotic reactions have been noted in vulnerable individuals, suicide attempts while intoxicated are rare and there are no known cases of a fatal LSD overdose (Passie et al. 2008). In contrast, despite the short duration for which NBOMes have been available, case reports have documented a range of adverse effects including tachycardia, palpitations, clonus, pyrexia, elevated creatine kinase, severe agitation, delirium, tonic-clonic seizures, renal failure, fatal overdoses and traumatic deaths (Hill et al. 2013; Poklis et al. 2014; Rose, Poklis, and Poklis 2013). Given the potency of this drug, it is impossible for users to estimate the dose by observation alone and therefore users can easily overdose. Additionally, even though NBOMes may mimic LSD’s psychoactive effects, a user who is specifically attempting to obtain LSD may nevertheless ingest NBOMe without knowing they are doing so. Indeed in this case, neither Mr. B nor the friend were aware of the actual substance contained on the blotter. Although it is possible Mr. B may have attempted suicide even if he had ingested LSD, this case illustrates the potential harm that may occur during an acute NBOMe intoxication.

The high potency and small dose ingested makes laboratory detection of NBOMes exceedingly difficult. Even facilities with advanced confirmatory testing capabilities will find it challenging to positively identify these compounds. As such, clinical suspicion must remain high for a possible NBOMe ingestion in patients reporting the use of any hallucinogen. Patients who are known to be using hallucinogens should be made aware of the potential for ingesting NBOMes even if their source is confident the substance is LSD. Additionally, users should be advised against using hallucinogens alone without a sober “sitter,” to use extreme caution when dosing to minimize the risk of overdose, and to avoid insufflating or injecting NBOMe hallucinogens.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

The study was funded in part by the Harvard Medical School Eleanore and Miles Shore Fellowship Program for Scholars in Medicine (JS), and National Institute of Health P30DA033934 (JP, AP).

References

- Braden Michael R, Parrish Jason C, Naylor John C, Nichols David E. Molecular Interaction of Serotonin 5-HT2A Receptor Residues Phe339(6.51) and Phe340(6.52) with Superpotent N-Benzyl Phenethylamine Agonists. Molecular Pharmacology. 2006;70(6):1956–64. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldicott David GE, Bright Stephen J, Barratt Monica J. NBOMe - a Very Different Kettle of Fish. The Medical Journal of Australia. 2013;199(5):322–23. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erowid Earth, Erowid Fire. Spotlight on NBOMes: Potent Psychedelic Issues. 2013 http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/nbome/nbome_article1.shtml.

- Halberstadt Adam L, Geyer Mark A. Effects of the Hallucinogen 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-Iodophenethylamine (2C-I) and Superpotent N-Benzyl Derivatives on the Head Twitch Response. Neuropharmacology. 2014;77(February):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.08.025.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill Simon L, Doris Tom, Gurung Shiv, Katebe Stephen, Lomas Alexander, Dunn Mick, Blain Peter, Thomas Simon HL. Severe Clinical Toxicity Associated with Analytically Confirmed Recreational Use of 25I-NBOMe: Case Series. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa) 2013;51(6):487–92. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.802795.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawn Will, Barratt Monica, Williams Martin, Horne Abi, Winstock Adam. The NBOMe Hallucinogenic Drug Series: Patterns of Use, Characteristics of Users and Self-Reported Effects in a Large International Sample. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England) 2014 Feb; doi: 10.1177/0269881114523866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninnemann Andrew, Stuart Gregory L. The NBOMe Series: A Novel, Dangerous Group of Hallucinogenic Drugs. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74(6):977–78. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passie Torsten, Halpern John H, Stichtenoth Dirk O, Emrich Hinderk M, Hintzen Annelie. The Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide: A Review. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 2008;14(4):295–314. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poklis Justin L, Charles Jezelle, Wolf Carl E, Poklis Alphonse. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Tandem Mass Spectrometry Method for the Determination of 2CC-NBOMe and 25I-NBOMe in Human Serum. Biomedical Chromatography: BMC. 2013;27(12):1794–1800. doi: 10.1002/bmc.2999.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poklis Justin L, Devers Kelly G, Arbefeville Elise F, Pearson Julia M, Houston Eric, Poklis Alphonse. Postmortem Detection of 25I-NBOMe [2-(4-Iodo-2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-N-[(2-Methoxyphenyl)methyl]ethanamine] in Fluids and Tissues Determined by High Performance Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry from a Traumatic Death. Forensic Science International. 2014;234(January):e14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2013.10.015.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose S Rutherfoord, Poklis Justin L, Poklis Alphonse. A Case of 25I-NBOMe (25-I) Intoxication: A New Potent 5-HT2A Agonist Designer Drug. Clinical Toxicology (Philadelphia, Pa) 2013;51(3):174–77. doi: 10.3109/15563650.2013.772191.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellpflug Samuel J, Kealey Samantha E, Hegarty Cullen B, Janis Gregory C. 2-(4-Iodo-2,5-Dimethoxyphenyl)-N-[(2-Methoxyphenyl)methyl]ethanamine (25I-NBOMe): Clinical Case with Unique Confirmatory Testing. Journal of Medical Toxicology: Official Journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 2013 Jul; doi: 10.1007/s13181-013-0314-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walterscheid Jeffrey P, Phillips Garrett T, Lopez Ana E, Gonsoulin Morna L, Chen Hsin-Hung, Sanchez Luis A. Pathological Findings in 2 Cases of Fatal 25I-NBOMe Toxicity. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 2014;35(1):20–25. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000082.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuba Dariusz, Sekuła Karolina, Buczek Agnieszka. 25C-NBOMe--New Potent Hallucinogenic Substance Identified on the Drug Market. Forensic Science International. 2013;227(1–3):7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]