Do you ever have days when you feel as though there is a steady parade of staff, supervisors, and corporate consultants looking to you to generate solutions to the ‘problem of the moment?’ Although Directors of Nursing (DONs), as leaders of nursing services, have the administrative authority and skills to be a natural source of help, this reveals the widely held assumption that the leader is the person in charge and that the person is charge is the one with the most knowledge to solve problems. This approach does not acknowledge what many DONs already know---most problems in nursing homes are complex, are difficult to resolve, and usually cannot be solved by any one leader.

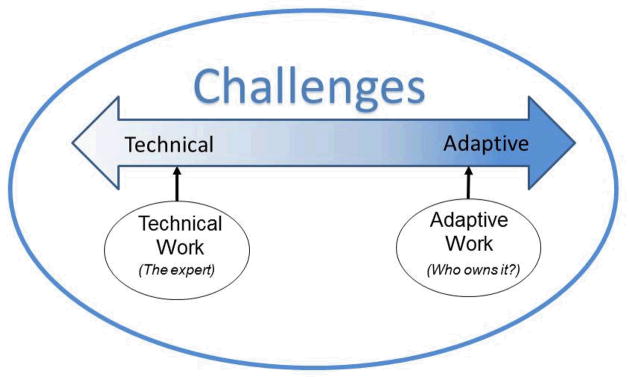

The adaptive leadership framework provides a novel way to think about leadership by differentiating between technical and adaptive challenges that arise in an organization (1). Technical challenges are problems or issues that are easily defined and can be solved with the right expertise, skill, or resources. Managers often solve these technical challenges by matching the technical challenge with the right policy, procedure, or finding the correct expertise. Leadership behaviors and skills needed to address technical challenges are those with which DONs are most familiar and comfortable. For example, if a DON aims to reduce adverse drug events, she or he could work with the nursing home administrator to implement a high risk drug alert system within the pharmacy ordering system (2). The technical challenge is identifying inappropriate medications or interactions, and is addressed with health information technology. The DON uses administrative skills to partner with the Nursing Home Administrator (NHA) to advocate for the new system and to balance the budget for the home.

However, problems in nursing homes are rarely purely technical and typically include adaptive challenges (3). Problems in complex environments such as nursing homes usually fall on a continuum, ranging from those with more technical elements to those with more adaptive elements (see Figure 1). Adaptive challenges are problems for which there are no known solutions; they require brainstorming and innovating new ways of accomplishing care and often require a change in attitudes, values or beliefs (3–6).

Figure 1.

The Continuum of Technical versus Adaptive Challenges.

Note: Revised with permission of the authors (12)

Drawing upon our previous example, adverse drug events do not occur solely because of the lack of clinical support decision tools to alert providers to potentially inappropriate medications or interactions. Clinical trials of these systems in nursing homes indicate adaptive challenges such as providers not using the system for certain conditions, or even ignoring system alerts (2). Rather, new solutions are needed and the best ideas are created by involving a variety of people such as providers, administrators and direct caregivers. By interacting with each other, these staff will exchange information about the various contributing factors, identify areas for new skill development, and learn new ways to provide care.

Implementing these new ways to provide routines—referred to as doing the ‘adaptive work’—can be accomplished only by those involved. For example, only the provider can change his or her attitude and learn new behaviors to use the drug alert system (3). The DON or NHA cannot do the actual work of changing attitudes, behaviors and learning, all of which are needed to accomplish new care to reduce adverse drug events. Therefore, adaptive challenges are owned by the person(s) with the challenge and only that person or group can do the necessary adaptive work. Adaptive leadership requires having the attitudes and skills necessary to distinguish between technical and adaptive challenges and appropriately aligning the solutions, using expertise where appropriate for the technical aspects and using adaptive approaches where necessary (6). Adaptive approaches are behaviors and strategies used to facilitate and support the adaptive work that others need to do to address their adaptive challenges. Developing adaptive leadership and approaches is difficult in a system replete with rules and regulations and a highly structured chain-of-command. The purpose of this study, therefore, was to describe examples of DONs using adaptive leadership to facilitate assessment, care planning, supervision and delegation.

Method

This paper uses data from a qualitative, comparative case study of ten nursing homes in two states that described the behaviors and strategies that RNs and LPNs use for assessment and care planning, supervision and delegation in the nursing home. In each of the ten nursing homes, at least one RN Director of Nursing, 1 RN and 1 LPN were interviewed by telephone to elicit descriptions of the specific behaviors and strategies used and the expected outcomes. The Directors of Nursing (DONs) were asked both about what they might do to assess, plan care, supervise, and delegate directly, as well as what they might do to guide their nurses in these areas of practice. The original study and results have been described in detail elsewhere (7).

Sample

Data from all 10 case study DONs were analyzed in this paper. These DONs were diverse in background, as well as the kinds of nursing homes in which they worked. Six of the DONs had an associate degree in nursing, three held a bachelor degree in nursing, and one had a diploma in nursing. Half of the DONs had held their current position for five years and the other half had been DONs for 10 or more years. Six of the ten nursing homes were for profit. The size of the nursing homes were evenly divided between less than and greater than the U.S. National average certified bed size of 106(8).

Data

Each DON interview was tape-recorded and transcribed for analysis; all identifying information was removed. Transcriptions were loaded into a qualitative data analysis program that only the study investigators could access on a secured, password-protected server.

Analysis

In the larger study, all interviews were coded for strategies that nurses described that related to assessment, care planning, supervision and delegation, using the template organizing style (9); the coding process has been described elsewhere (7). Data coded as strategies by DONs were read by the first author for examples of adaptive leadership in relation to assessment, care planning, delegation and supervision and placed in a summary table which was reviewed by the second author of the paper.

Results

Assessment and care planning

We were able to identify several examples of DONs’ leadership behaviors that demonstrated adaptive leadership. These related to several aspects of the assessment and care planning process, including how to incorporate staff nurses’ assessments into care plans, how to involve families in the care planning process, and how to address an emergent resident care issue. Below, we discuss these three themes related to assessment and care planning.

Data about how to incorporate staff nurses’ assessments into care planning revealed both technical and adaptive challenges. Technical challenges included such aspects as how to have licensed nurses document their contributions to the assessment and care planning process in a standardized way, or how to validate that the MDS nurse has collected data from floor nurses and nursing assistants to compare data with what is currently recorded in the MDS care plan. Developing clear documentation forms to be completed and audited on a routine basis, or requiring the MDS nurse to validate data with floor staff, were technical strategies used to address these technical challenges.

However, there were also adaptive challenges that related to how to incorporate staff nurses’ assessments into care planning, which, if ignored, would result in the missed opportunity to generate real-time care plans that guide care that reflect diverse perspectives and information about resident needs and preferences. DON 1 described how she found that relying on formal care planning meetings did not generate innovative care solutions or ensure that all relevant assessment data were brought to the table to help the resident. Instead, she convened informal meetings on the units to facilitate nursing staff in doing the ‘adaptive work’ needed to generate practical new ideas and bring them to fruition. This required staff to learn to integrate collected data and observations from diverse people into assessments and care plans and to create ways to implement these integrated care plans.

[care planning is]… not going down and sitting in a room with a stack of papers and say, “tell me about”, you know, “we’re going to look at this and that”. It is more… meet up at the nurse’s station and say, “What have you noticed? How is she doing with this or that?” And then, formulate that way… we just…gather at like the change of shift…and just quickly discuss residents and what’s working and what’s not working. Then an RN takes that and develops a plan of care.

DON 1

How to involve families in care planning also included technical and adaptive challenges. A technical challenge, for example, was how to ensure that the families are informed and invited to participate in the care planning process. Policies and procedures can be developed to ensure that the social work department contacts family members in a timely way with comprehensive information about the time and location of a care planning meeting.

Numerous adaptive challenges related to how to incorporate families into care planning, such as eliciting family preferences, balancing preferences with what is feasible, or addressing conflicts among family members. Ignoring the adaptive challenges and focusing exclusively on the administrative processes related to family participation (i.e., only addressing technical challenges), resulted in, at best, no new solutions to care issues and, at worst, alienated families in care; examples of missed opportunities. DON 4 described how she participated in care planning meetings with family by attending meetings at random because, “it gives me the opportunity to have face time with family members…[and]…I’ve had issues in the past where care plan meetings were not professional, and I always like to keep staff on their toes.” Rather than facilitating the adaptive work that her staff and family members needed to do to generate new attitudes and understand care issues and resident preferences (the lack of which may have caused the unprofessional behaviors she described), she used a technical approach of randomly ‘auditing’ and monitoring for undesirable staff behaviors.

In contrast, DON 1 provided an example of adaptive leadership by describing how she sits with staff and family and asks question to stimulate new ideas, and serves as a resource to both staff and families as they do the adaptive work of generating a resident-centered care plan. She described, “I usually get involved if it encompasses multiple disciplines or if it’s a very complicated family… and be that liaison …to pull those things together… You know, it’s not a black or white situation.” Not being “black and white” is a great way to describe adaptive challenges.

Similarly, how to assess and plan care in an emergent resident care situation or incident contained both technical and adaptive challenges. Technical challenges related to how to notify a supervisory nurse or a physician promptly, or how to ensure that a standardized set of information was provided over the telephone to the medical staff when making a determination of whether hospitalization is required. Such challenges were addressed by implementing new policies or procedures using technical solutions.

Adaptive challenges, however, centered on how gather all relevant assessment data and observations or how to problem-solve together to address the incident or situation and incorporate a solution into the plan of care. Both DON 7 and DON 9 provided examples of using adaptive leadership to facilitate the adaptive work necessary to generate new understandings and novel care plans to address problems or incidents. Specifically, both DON 7 and DON 9 expressed a fundamental belief that it is necessary to seek multiple, diverse perspectives to ensure new understandings of what may be occurring with a resident; they expected staff also to embrace this belief. As described by DON 7 in her approach to assessment and care planning, “there’s a scripture that I like to think about…’there’s wisdom in a multitude of council.’ In other words, there’s no way that I know it all…Even if I think I know something…I will call and …[identify someone to]…bounce it off.” DON 9 explained,

Don’t leave any stone unturned and let’s all talk about it because 10 minds are better than one and somebody’s always going to come up with an idea that, ‘Oh boy, that’s good, we didn’t think of that’…[a resident]…has a bruise on her elbow. Well, she is wheeling around this building ALL day long. Who knows where she tapped her elbow, you know and what are we going to do about it? So, the encouragement is there for good communication and with a lot of people and to utilize everybody that we can in the building, whether it’s a CNA or all the way up.

DON 9

Supervision/delegation

Several examples of adaptive leadership were identified among the ten DONs regarding supervision and delegation. One theme that emerged was how DONs chose to address staff members who did not meet performance expectations or benchmarks. Staff noncompliance or substandard performance were viewed as technical challenges in that management expertise was required to review performance and determine whether expectations were met or not met. Strategies such as audit checklists and written performance evaluations by direct supervisors provided critical, systematic procedures to address these technical challenges.

Identifying and addressing the adaptive challenges inherent in addressing noncompliance or substandard performance, however, required adaptive leadership. When staff members needed to learn new approaches, or adopt new perspectives, adaptive leadership was required. Identifying these issues required adaptive approaches by the DON; however, addressing these issues required adaptive work that only the staff member could do. New behaviors and attitudes cannot be implemented simply by enacting a new rule or policy. DON 2 provided an example of what happens when performance issues are addressed as purely a technical challenge. In this example, the DON felt chronic frustration at staff noncompliance and she addressed it by continuing to “retrain” a staff member in what he or she was supposed to be doing until eventual termination. She stated, “when they’re not doing that correctly, we go back and retrain… and if that doesn’t work…we retrain…on an individual basis and… [if]…that fails…that’s when we have to think about the termination process…So we have to constantly be out there and retrain.” By contrast, DON 9 provided an example of adaptive leadership by trying to identify what the inherent adaptive challenges might be,

If there are problems with performance, I guess I try to take the approach as, ‘Do they really understand how to do the job?’ and I will sit with a nurse and review policy and procedure, go over an incident report that doesn’t seem to be completed accurately or in depth, rather than just jumping to corrective actions.

DON 9

By asking questions and exploring what the challenges might be, this DON facilitated the identification of the adaptive challenges that will need to be addressed to improve the staff member’s performance.

Discussion

When DONs as adaptive leaders distinguish technical from adaptive challenges, they refocus their attention to engage others in problem resolution, because the DON alone cannot do the ‘adaptive work’ necessary to address the challenge. Rather, the focus is how to develop adaptive approaches to shift the attitudes of staff members to own their adaptive challenges and to develop the staff members’ skill for doing adaptive work. Understanding the differences between technical and adaptive challenges, therefore, is a critical step to addressing more fully the types of challenges that arise in the nursing home setting.

The examples described by the DONs in this study illustrated that most challenges faced in nursing homes include both technical and adaptive challenges. Thus, the DON’s administrative expertise is essential in addressing challenges, but it is not sufficient. DONs who ignored the adaptive aspect of problems and addressed only the technical aspect of challenges, found themselves facing staff terminations or missed opportunities for assessment and care planning to address resident-centered care comprehensively.

In this study, examples of DONs exemplifying adaptive leadership were found. Their adaptive leadership strategies were comprised primarily of behaviors such as asking questions, seeking different perspectives, facilitating discussion among staff from multiple levels in the organization, and providing the opportunity for brainstorming and problem-solving. As described by Anderson et al (10), such strategies are fundamental ways to interact effectively in nursing homes; they comprise the engine that drives the nursing home (11). Table 1 summarizes several of these strategies, which provide a starting point for developing adaptive leadership. By helping staff to learn and practice such behaviors, staff throughout a facility can improve their capacity to address adaptive challenges, ultimately to improve quality of care.

Table 1.

Sample Strategies for Adaptive Leadership from Anderson’s Local Interaction Strategies (10).

| Local Interaction Strategy | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Sensemaking | Talk with other people to figure out or understand confusing situations or information together | Bring together staff and generate discussion about what some of the adaptive challenges might be in a problem |

| Ask Questions | Ask for explanation when you feel unclear or uncertain about something | Assume that all problems have both technical and adaptive components; ask questions to begin to identify and explore those adaptive components |

| Be Approachable | Be open, listen, & respond to what people say | Listen carefully for cues that indicate adaptive challenges, such as when normative beliefs or values are involved |

| Suggest Alternatives | Give different options for others to consider before taking action | Facilitate staff members doing the adaptive work themselves by suggesting alternatives rather than providing a new policy or procedure (a technical solution) |

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Council of State Boards of Nursing Center for Regulatory Excellence (R30010 PI: Corazzini PI), and the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (1P30NR014139-01 PI: Anderson; R56NR003178 and R01NR003178 Co-PIs: Anderson and Colón-Emeric).

References

- 1.Uhl-Bien M, Marion R, McKelvey B. Complexity leadership theory: Shifting leadership from the industrial age to the knowledge era. The Leadership Quarterly. 2007;18(4):298–318. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clyne B, Bradley MC, Hughes C, Fahey T, Lapane KL. Electronic prescribing and other forms of technology to reduce inappropriate medication use and polypharmacy in older people: a review of current evidence. Clin Geriatr Med. 2012 May;28(2):301–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2012.01.009. Epub 2012/04/17. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey DE, Docherty S, Adams JA, Carthron DL, Corazzini K, Day JR, et al. Studying the Clinical Encounter with the Adaptive Leadership Framework. Journal of Healthcare Leadership. 2012;4:83–91. doi: 10.2147/JHL.S32686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thygeson M, Morrissey L, Ulstad V. Adaptive leadership and the practice of medicine: a complexity-based approach to reframing the doctor–patient relationship. J Eval Clin Pract. 2010;16(5):1009–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichtenstein BB, Uhl-Bien M, Marion R, Seers A, Orton JD, Schreiber C. Complexity leadership theory: An interactive perspective on leading in complex adaptive systems. Emergence: Complexity and Organization. 2006;8(4):2–12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heifetz RA, Grashow A, Linsky M. The practice of adaptive leadership: Tools and tactics for changing your organization and the world. Harvard Business Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corazzini KN, Anderson RA, Mueller C, Hunt-McKinney S, Day L, Porter K. Patterns of Nursing Practice in Nursing Homes: How RNs and LPNs Enact their Scopes of Practice. Journal of Nursing Regulation. 2013;14(1):14–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.American Health Care Association. LTC Stats: Nursing Facility Operational Characteristics Report. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Anderson RA, Corazzini K, Porter K, Daily K, McDaniel RR, Colón-Emeric C. CONNECT for Quality: Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Trial to Improve Fall Prevention in Nursing Homes. Implementation Science. 2012;7(2) doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-11. Internet. Available from: Open access: http://www.implementationscience.com/content/7/February/2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson RA, Ammarell N, Bailey DE, Colon-Emeric C, Corazzini K, Lekan-Rutledge D, et al. The power of relationship for high quality long term care. J Nurs Care Qual. 2005;20(2):103. doi: 10.1097/00001786-200504000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson RA, Docherty S, Brandon D, Bailey D, Corazzini K. Using Adaptive Leadership Framework and Trajectory Science Methods for Research in Chronic Illness and Care Systems. 24th International Nursing Research Congress of Sigma Theta Tau International; July 26, 2013; Prague, Czech Republic. 2013. [Google Scholar]