Abstract

Purpose: To investigate the efficacy and mechanisms of non-c-Myc induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) transplantation in a rat model of retinal oxidative damage.

Methods: Paraquat was intravitreously injected into Sprague–Dawley rats. After non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation, retinal function was evaluated by electroretinograms (ERGs). The generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) was determined by lucigenin- and luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence. The expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, ciliary neurotrophic factor, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1α, and CXCR4 was measured by immunohistochemistry and ELISA. An in vitro study using SH-SY5Y cells was performed to verify the protective effects of SDF-1α.

Results: Transplantation of non-c-Myc iPSCs effectively promoted the recovery of the b-wave ratio in ERGs and significantly ameliorated retinal damage. Non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation decreased ROS production and increased the activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase, thereby reducing retinal oxidative damage and apoptotic cells. Moreover, non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation resulted in significant upregulation of SDF-1α, followed by bFGF, accompanied by a significant improvement in the ERG. In vitro studies confirmed that treatment with SDF-1α significantly reduced apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner in SH-SY5Y cells. Most transplanted cells remained in the subretinal space, with spare cells expressing neurofilament M markers at day 28. Six months after transplantation, no tumor formation was seen in animals with non-c-Myc iPSC grafts.

Conclusions: We demonstrated the potential benefits of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation for treating oxidative-damage-induced retinal diseases. SDF-1α and bFGF play important roles in facilitating the amelioration of retinal oxidative damage after non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation.

Introduction

Oxidative stress has been implicated in many retinal diseases, including age-related macular degeneration and proliferative diabetic retinopathy.1–4 These diseases are the leading causes of blindness in developed countries. For most oxidative-stress-induced retinal diseases, the loss of retinal neurons is generally irreversible and results in blindness. Until recently, no effective treatment was available to repair damaged retinas in these diseases. Stem-cell-based therapies are considered novel strategies for treating incurable retinal diseases.

Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have the potential for multilineage differentiation and can be a resource for stem-cell-based treatment. iPSCs can be induced from somatic cells through reprogramming by transduction with defined transcription factors.5,6 iPSCs have been shown to be less immunorejective and lack the ethical concerns of embryonic stem cells.7 iPSCs can differentiate into various types of retinal cells,8,9 showing potential as replacement tissue for retinal diseases. However, this concept was challenged by recent observations that only small numbers of transplanted cells engraft into tissues. Increasing evidence has demonstrated that paracrine mechanisms, including anti-inflammatory activity and the release of neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), account for the therapeutic benefits of stem cells in experimental animal models.10–12

Stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1α, a CXC chemokine, is a potent chemoattractant for leukocytes, endothelial progenitors, and hematopoietic stem cells.13 CXCR4 is the receptor for SDF-1, and the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis plays important roles in inflammation, tissue repair, and organogenesis.14 Several studies have demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cells can secrete SDF-1α and promote the survival and regeneration of progenitor cells and cardiac myocytes.15–17 However, it remains unclear whether, after iPSC transplantation, SDF-1α is involved in and regulates the recovery process after retinal oxidative damage.

Paraquat (PQ) is a bipyridyl herbicide capable of generating oxygen radicals. Cingolani et al. demonstrated that intravitreous injection of PQ induced diffuse oxidative damage to the retina in C57BL/6 mice. This oxidative damage resulted in apoptotic cell death, retinal morphologic changes, and reduced retinal function.18 In addition, intravitreous PQ injection is safe for local exposure of the retina, without systemic side effects. Therefore, intravitreous PQ injection is a good model for oxidative-damage-induced retinal diseases.

In this study, we attempted to reduce the incidence of teratoma formation after transplantation of iPSCs by using iPSCs without exogenous c-Myc. We evaluated the therapeutic effects of non-c-Myc iPSCs in a rat model of oxidative-damage-induced retinal diseases and explored possible mechanisms, specifically focusing on the roles of SDF-1α. In addition, we evaluated the safety of transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs by assaying for tumor formation 6 months after transplantation.

Methods

Reagents

PQ was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. A DNA fragmentation detection kit (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-biotinide end labeling [TUNEL]) was obtained from Calbiochem. The GFP antibody was purchased from BioVision. Mounting medium with DAPI and phycoerythrin streptavidin antibody were obtained from Vector Laboratories. Anti-nitrotyrosine was obtained from Abcam, anti-8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine was from JaICA, and anti-conjugated acrolein antibody was from Advanced Targeting Systems. Anti-CNTF and anti-bFGF antibodies were purchased from Millipore. Anti-BDNF and anti-CXCR4 antibodies were from Epitomics. Anti-mouse/rat SDF-1α-purified antibody was from eBioscience. Mouse anti-neurofilament-M was from Invitrogen.

iPSC culture

We generated mouse iPSCs with only 3 exogenous genes (Oct4/Sox2/Klf4) and without the oncogene c-Myc. Murine iPSCs were generated from mouse embryonic fibroblasts derived from 13.5-day-old embryos of C57/B6 mice. The iPSCs were reprogrammed by transduction with retroviral vectors encoding 3 transcription factors, Oct-4, Sox2, and Klf4, as described previously.19 Undifferentiated iPSCs were routinely cultured and expanded on mitotically inactivated murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs; 50,000 cells/cm2) in 6-well culture plates (BD Technology) in the presence of 0.3% leukemia inhibitory factor in iPSC medium. Every 3–4 days, colonies were detached with 0.2% collagenase IV, dissociated into single cells with 0.025% trypsin and 0.1% chicken serum in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and plated again onto MEFs. The non-c-Myc iPSCs were pluripotent and could be differentiated into 3 dermal-lineage cell types, including astroglial (neuroectodermal), osteogenic (mesodermal), and hepatocyte-like (endodermal) lineage cells, as described previously.19,20

Animals and the retinal oxidative stress animal model

Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats weighing 150–200 g were used in all subsequent experiments. All animal experiments in this study adhered to the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research.

In an established animal model of retinal oxidative damage, 1 μL of 0.5 mM PQ was injected into the vitreous cavity of rats.21 The rats were anesthetized with intraperitoneal 2% pentobarbital (40 mg/kg) and topical 1% proparacaine eye drops. Pupil dilation was achieved with 1% tropicamide. Sclerotomy was performed 1 mm behind the limbus with the tip of a 27-gauge needle. A 33-gauge blunt-tip needle (Hamilton) was inserted into the vitreous cavity, and 1 μL of PQ was injected. The needle was left in the vitreous cavity for 1 min after injection to reduce the degree of reflux.

Animal grouping and subretinal cell transplantation

SD rats were randomly divided into 4 groups:

Group 1: Intravitreous injection of PBS, serving as a normal control (normal).

Group 2: Intravitreous injection of 0.5 mM PQ (PQ-injected group).

Group 3: Subretinal injection of MEFs 2 h after PQ injection (MEF-treated group).

Group 4: Subretinal injection of iPSCs 2 h after PQ injection (iPSC-treated group).

Total numbers of animals used in each group and the days to perform the experiments were summarized in Table 1. The treatment was blinded to the experimenter.

Table 1.

Summary of Total Number of Animals in Each Group per Experiment and Days to Perform the Experiments

| Experiments | Number of animals in each group (N) | Days after treatment |

|---|---|---|

| ERG | 10 | Days 3, 7, 14, 21, 28 |

| Histology | 3 | Day 14 |

| TUNEL and caspase III stain | 3 | Day 7 |

| Immunofluorescence | ||

| Nitrotyrosine, 8-OHdG, acrolein | 3 | Day 14 |

| SDF-1α, CXCR4 | 3 | Day 14 |

| bFGF, CNTF, BDNF | 3 | Day 14 |

| CM-DiL | 3 | Days 14, 28 |

| ELISA | ||

| MDA, 8-OHdG | 3 | Day 14 |

| SDF-1α | 3 | Days 3, 7, 14, 21 |

| bFGF, CNTF, BDNF | 5 | Days 3, 7, 14, 21 |

| Chemiluminescence | 3 | Days 7, 14, 21 |

| Antioxidative enzymes | 3 | Days 7, 14, 21 |

| Western blot analysis– CXCR4 | 3 | Day 7 |

BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor; ERG, electroretinogram; SDF, stromal cell-derived factor; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-biotinide end labeling.

The right eye of each animal received injections. Rats were anesthetized, and pupils were dilated. The eyes were gently protruded using a rubber sleeve. A 90° peritomy was made in the temporal quadrant, and a sclerotomy was made with a 27-gauge needle. A 33-gauge blunt-tip needle was inserted tangentially toward the posterior pole of the eye, and 1 μL of iPSC suspension (∼1×105 cells/mL) or 1 μL of MEF suspension was slowly injected into the subretinal space. Rats were sacrificed and the eyes were enucleated 3, 7, 14, 21, or 28 days after treatment.

Electroretinogram recordings

Rats were dark-adapted for 1 h before performing the electroretinograms (ERGs). All manipulations were done in dim red light illumination. After being anesthetized, the rats were placed on a heating pad, and a recording electrode was placed on the cornea after application of 0.5% methyl cellulose. A reference electrode was attached to the shaved skin of the head, and a ground electrode was clipped to the rat's tail. A single flash of light (duration=100 ms) 30 cm from the eye was used as the light stimulus. Responses were amplified with a gain setting of±500 μV and filtered with low (0.3 Hz)– and high (500 Hz)–frequency cutoffs from an amplifier. The pattern of the a- and b-waves was recorded. The b-wave ratio was defined as the b-wave amplitude of the right eye divided by the b-wave amplitude of the left eye. The fold of the b-wave ratio represented the b-wave ratio at days 3, 7, 14, 21, or 28 divided by the b-wave ratio at day 0.

Histological study and retinal cell count

For every control and experimental animal, both eyes were collected 14 days after treatment. The specimens were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 30 min at 4°C and then washed with PBS. Five-micrometer sections were obtained using a cryostat, and some preparations were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for morphological observations and retinal cell counts.

For retinal cell counts, the estimation of retinal rescue was made by comparing the total number of cells in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), the inner nuclear layer (INL), and the outer nuclear layer (ONL) of each eye. The total number of cells in the GCL, INL, and ONL were counted along ventral retinal sections from one margin to the other, indicated as areas 1 to 6, each 250 μm in length along the section. The result was expressed as the cell number per 250 μm of the retina.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-biotinide end labeling

TUNEL assays were performed at day 7 using a DNA fragmentation detection kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Sections were visualized on a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Instruments). The mean number of TUNEL-positive retinal cells per 250 μm length of retina section was counted.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was carried out by simultaneously blocking and permeabilizing sections with 0.2% Triton in PBS containing 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, incubating with primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C, and then incubating with the appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies (all diluted 1:1,000) in blocking solution for 3 h at room temperature. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Primary antibodies included GFP (1:5,000), caspase 3 (1:200), acrolein (1:200), nitrotyrosine (1:200), 8-OhdG (1:200), BDNF (1:200), CNTF (1:200), bFGF (1:200), stromal cell-derived factor (SDF)-1α (1:200), and CXCR4 (1:100). Specimens stained with IgG isotype antibody as the primary antibody were used as negative controls. The mean number of caspase 3-positive retinal cells per 250 μm length of retina section was counted.

The following formula was used for the densitometric quantitation of acrolein, nitrotyrosine, 8-OHdG, bFGF, CNTF, and BDNF immunohistochemistry, as previously described.21

Immunostaining index=Σ [(X − threshold)×area (pixels)]/total cell number. Where X is the staining density indicated by a number between 0 and 256 in grayscale, and X is more than the threshold. Briefly, digitized color images were obtained as PICT files. PICT files were opened in grayscale mode using NIH image, ver. 1.61. Cell numbers were determined using the Analyze Particle command after setting a proper threshold.

The relative density of immunostaining was defined as immunostaining index of PQ-injected, MEF-treated, and iPSC-treated groups divided by immunostaining index of normal group.

Measurement of reactive oxygen species in the retina

Luminol and lucigenin chemiluminescence (CL) was measured as indicator of free-radical formation. Rats were sacrificed at days 7 and 14, and retinas were isolated and then homogenized in PBS. Lucigenin (bis-N-methylacridinium nitrate) and luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Measurements were made at room temperature using a luminescence reader (Aloka Co.). Specimens were put into vials containing PBS-HEPES buffer. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were quantified after the addition of enhancers, such as lucigenin or luminol, at a final concentration of 0.2 mM. Counts were obtained at 1-min intervals, and the results were given as the area under the curve for a counting period of 5 min. Counts were corrected for wet tissue weight (rlu/mg tissue).

Measurements of the activities of antioxidant enzymes in the retina

The levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase activities in the retina were determined by colorimetric assays at days 7, 14, and 21. Both SOD and catalase assay kits were purchased from Cayman Chemical. Assay procedures and tissue homogenate preparations were performed following the manufacturer's instructions.

Measurement of oxidative damage in the retina

The levels of MDA and 8-OHdG in the retina were measured at day 14 using MDA and 8-OHdG ELISA kits (Cayman Chemical and Cosmo Bio. Co.). The procedure was as described in the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad).

Measurement of the expression of bFGF, CNTF, BDNF, and SDF-1α in the retina

The retinas of each group were harvested at days 3, 7, 14, and 21. These retinas were homogenized in 1 mL of PBS containing antiproteases (0.1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.1 mM benzethonium chloride, 10 mM EDTA, and 20 kallikrein inhibitor unit aprotinin A) and 0.05% Tween 20. The samples were then centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min, and the supernatants were immediately assayed using the bFGF and CNTF and BDNF ELISA kit (Cusabio), and SDF-1α ELISA kit (Eagle Bioscience).

Western blot analysis

The rats in each group were sacrificed, and retinas were isolated at day 7. Total protein was extracted from the retinas by lysing the sample in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. The extract and Laemmli buffer were mixed in a 1:1 ratio, and the mixture was boiled for 5 min. Samples (100 μg) were separated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and then transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon-P; Millipore Corp.). The membranes were incubated with anti-CXCR4, anti-Bcl-2, and anti-β-actin antibodies. The membranes were subsequently incubated with horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and visualized by CL (GE Healthcare). The density of the blots was quantified using image-analysis software after scanning the image (Photoshop, version 7.0; Adobe Systems). The optical densities of each band were calculated and standardized based on the density of the β-actin band.

SH-SY5Y cell culture and oxidative insult in vitro

SH-SY5Y cells were obtained from the Bioresource Collection and Research and used for in vitro studies. SH-SY5Y cells were incubated in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 and 95% air incubator. For the oxidative insult, PQ was diluted in culture medium to the final concentration of 100, 500, or 1,000 μM immediately before use. Cells were seeded on coverslips for 24 h and treated with various concentrations of PQ for another 24 h. The protocol utilized for TUNEL staining was as described previously. Cells were counterstained with DAPI. The TUNEL assay results were examined by immunofluorescence microscopy.

Effects of SDF-1α on cell apoptosis in PQ-induced SH-SY5Y cells

Human recombinant SDF-1α (Peprotech) was dissolved in PBS. SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with each concentration of SDF-1α (0, 0.1, 1, 10, or 50 ng/mL) for 30 min. After SDF-1α treatment, cells were exposed to 1,000 μM PQ for 24 h at 37°C and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for TUNEL analysis.

SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with 10 ng/mL SDF-1α for 30 min and then exposed to 1,000 μM PQ for 24 h. Western blot analysis was used to determine the expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2, as described previously.

Assessment of tumor formation after subretinal transplantation of non-c-Myc iPSCs

To assess whether iPSCs lacking exogenous c-Myc reduced the incidence of tumorigenesis, either 3 genes (Oct4/Sox2/Klf4) or 4 genes (Oct4/Sox2/Klf4/c-Myc) were delivered using a lentiviral vector. The tumorigenic ability of the different iPSC grafts was compared after PQ injection and intravitreous cell transplantation for 6 months after treatment. Retinal sections with H&E staining were performed to evaluate the incidence of teratoma formation.

Statistical analysis

All data are shown as means±standard errors of means. Statistical analysis was performed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's post hoc analysis for multiple comparisons with the computer software Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS 15.0; SPSS, Inc.). Differences in the means between 2 groups were assessed with an unpaired, 2-tailed t-test. A value of P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on ERGs

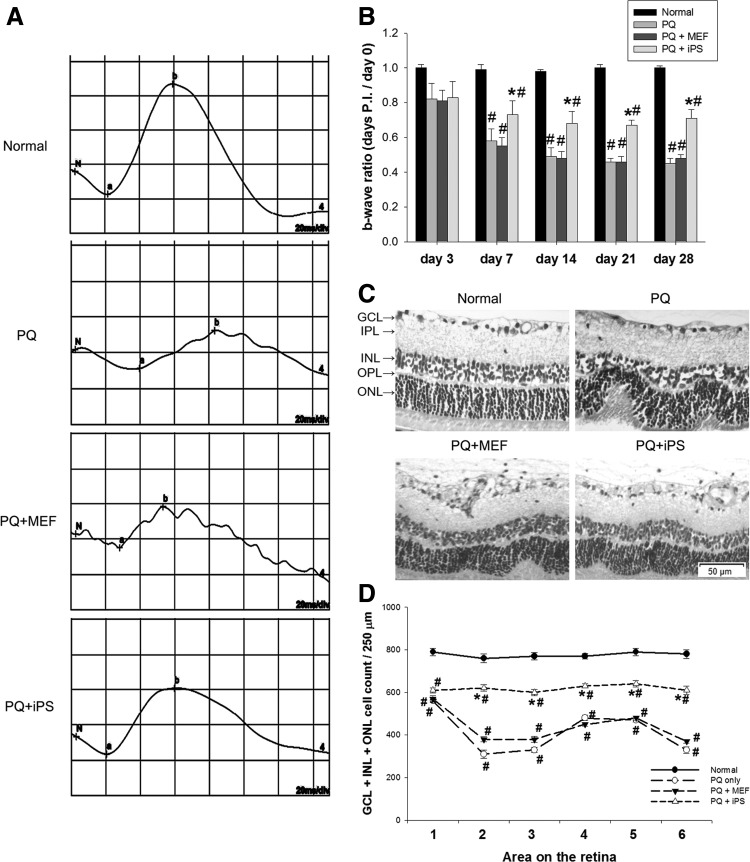

Three days after injection of 0.5 mM PQ, the b-wave ratio on the ERG was reduced in each treatment group. There was no significant difference in b-wave ratio between the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated, PQ-injected, and MEF-treated groups 3 days after transplantation (P>0.05, 1-way ANOVA). However, the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated group enhanced the recovery of the b-wave ratio at 7, 14, 21, and 28 days after transplantation. The b-wave ratio reached statistical significance in the iPSC-treated group after 7, 14, 21, and 28 days compared with the PQ-injected and MEF-treated groups (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=10 in each group) (Fig. 1A, B).

FIG. 1.

Effects of subretinal transplantation of non-c-Myc induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) on electroretinogram (ERG) b-wave amplitudes, retinal morphology, and the number of outer nuclear layer (ONL) cells. (A) Typical individual ERG recordings from the 4 groups at day 14 after treatment. (B) Mean ERG b-wave amplitude was measured at days 3, 7, 14, 21, and 28 after treatment. The b-wave ratio was defined as the b-wave amplitude of the right eye divided by the b-wave amplitude of the left eye at the specific time point. The fold of the b-wave ratio represents the b-wave ratio at days 3, 7, 14, 21, or 28 divided by the b-wave ratio at day 0 (N=10 in each group). (C) Retinal sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) at day 14 after treatment. (D) The total number of cells in the ganglion cell layer (GCL), inner nuclear layer (INL), and ONL at day 14 was counted along ventral retinal sections from one margin to the other, and labeled as areas 1 to 6, each 250 μm in length along the section. The result is expressed as the cell number per 250 μm of retina (N=3 in each group). Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. The GCL, inner plexiform layer (IPL), INL, outer plexiform layer (OPL), and ONL are labeled in the micrograph. *P<0.05 compared with the “PQ” and “PQ+MEF” groups; #P<0.05 compared with the “normal” group; by 1-way ANOVA. ANOVA, analysis of variance; MEF, murine embryonic fibroblast; PQ, paraquat; SEM, standard error of mean.

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on retinal morphology and outer nuclear cell number

There was thinning of the INL and ONL, and folds in the ONL at day 14 in the retinas of PQ-injected and MEF-treated groups. Non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas showed better preservation of the INL and ONL, with less prominent folds in the ONL (Fig. 1C). Significantly more total number of cells in the GCL, INL, and ONL was counted in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas than in MEF-treated or PQ-injected retinas (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 1D).

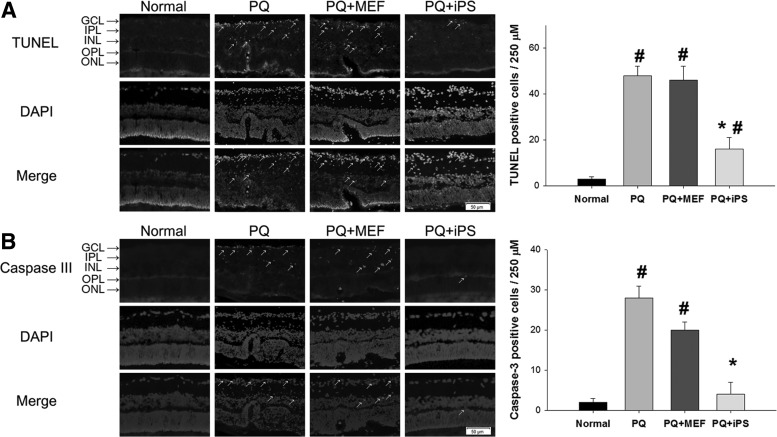

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on retinal apoptosis

More TUNEL-positive cells in the GCL, INL, and ONL were noted in MEF-treated and PQ-injected retinas, while only sparse TUNEL-positive cells were noted in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas at day 7. After counting the number of apoptotic cells, there were statistically fewer apoptotic cells in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas than in MEF-treated and PQ-injected retinas (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on retinal apoptosis. Retinal sections were stained with TUNEL and caspase 3, and the mean number of TUNEL- or caspase 3-positive retinal cells per 250 μm section of retina was counted at day 7. (A) More TUNEL-positive cells in GCL, INL, and ONL were observed in MEF-treated and PQ-injected retinas (arrows). There were statistically fewer TUNEL-positive, counted cells in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas than in MEF-treated and PQ-injected retinas. (B) Few caspase 3-positive cells in the INL of the retina were noted in iPSC-treated retinas. There were also statistically significantly less caspase 3-positive cells in iPSC-treated retinas than in MEF-treated or PQ-injected retinas (arrows) (N=3 in each group). Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. *P<0.05 compared with the “PQ” and “PQ+MEF” groups; #P<0.05 compared with the “normal” group; by 1-way ANOVA. TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase–mediated dUTP-biotinide end labeling.

Similarly, non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas had significantly fewer caspase 3-positive cells in the retinas compared with MEF-treated and PQ-injected retinas at day 7 (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 2B).

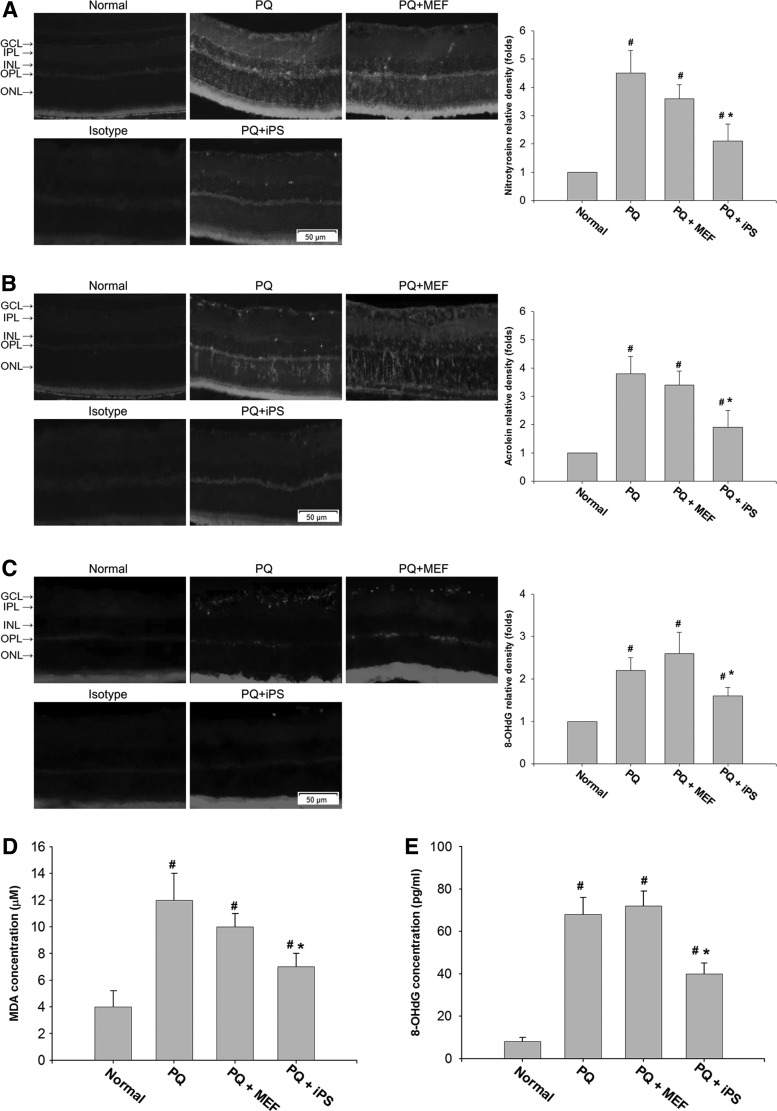

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on retinal oxidative damage

We examined the retinal oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA by staining retinal sections with nitrotyrosine, acrolein, and 8-OHdG at day 14 after treatment. PQ injection resulted in an increase in immunohistochemical staining for nitrotyrosine, acrolein, and 8-OHdG in the retinas. Non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas showed decreased staining for nitrotyrosine, acrolein, and 8-OHdG, especially in the GCL and ONL, compared with PQ-injected retinas and MEF-treated retinas (Fig. 3A–C).

FIG. 3.

The effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on oxidative damages to the retina. Retinal oxidative stress in each group was detected by immunohistochemical staining of (A) nitrotyrosine, (B) acrolein, and (C) 8-OHdG at day 14 after transplantation. PQ injection resulted in an increase in immunohistochemical staining for nitrotyrosine, acrolein, and 8-OHdG in the retinas. Non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas showed decreased staining for nitrotyrosine, acrolein, and 8-OHdG compared with PQ-injected or MEF-treated retinas. Specimens stained with IgG isotype antibody as the primary antibody were used as negative controls. The levels of (D) MDA and (E) 8-OHdG in the retinas, which represent oxidative damage to lipids and DNA, were examined at day 14 by ELISA. iPSC-treated retinas showed significantly reduced levels of MDA and 8-OHdG at day 14 compared with the PQ-injected or MEF-treated groups (N=3 in each group). Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. *P<0.05 compared with the PQ- or MEF-treated groups; #P<0.05 compared with the normal group; by 1-way ANOVA.

ELISA analysis showed that the levels of MDA and 8-OHdG, which represent oxidative damage to lipids and DNA, were significantly reduced in the iPSC-treated retinas at day 14 compared with the PQ-injected or MEF-treated groups (P<0.05 and P<0.05, respectively, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 3D, E).

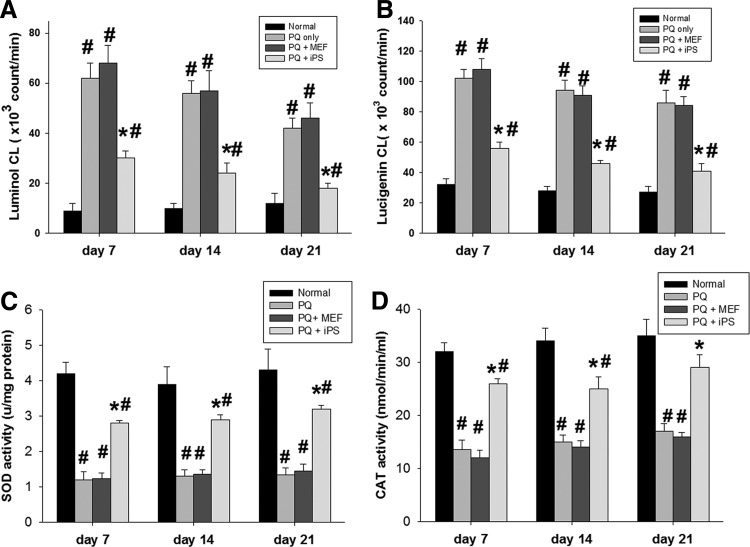

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on retinal free-radical production

The generation of ROS in the retinas was examined using lucigenin- and luminol-enhanced CL. Non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas showed statistically significant decreases in mean luminol- and lucigenin-enhanced CL at days 7, 14, and 21 compared with MEF-treated or PQ-injected retinas (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 4A, B).

FIG. 4.

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on retinal reactive oxygen species and antioxidant enzyme activity. (A) iPSC-treated retinas showed a statistically significant reduction of luminol- and (B) lucigenin-enhanced chemiluminescence compared with PQ-injected retinas and MEF-treated retinas at days 7, 14, and 21. (C) Untreated retinas and MEF-treated retinas showed significantly decreased activity of SOD and (D) CAT enzymes 7 days after injury compared with iPSC-treated retinas. iPSC treatment significantly attenuated the decrease of SOD and CAT activity at days 7, 14, and 21 after transplantation (N=3 in each group). Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. *P<0.05 compared with the “PQ” and “PQ+MEF” groups; #P<0.05 compared with the “normal” group; by 2-way ANOVA. CAT, catalase; SOD, superoxide dismutase.

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on the activity of antioxidant enzymes

SOD and catalase (CAT) are the most important enzymes of the antioxidant defense system. As shown in Fig. 4C and D, intravitreal injection of PQ resulted in a significant decrease in the activity of SOD and CAT enzymes compared with the normal control (P<0.05, 2-tailed Student's t-test; N=3 in each group). However, subretinal transplantation of iPSCs significantly attenuated the decrease of SOD and CAT activity at days 7, 14, and 21 compared with MEF-treated or PQ-only groups (P<0.05, 2-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group).

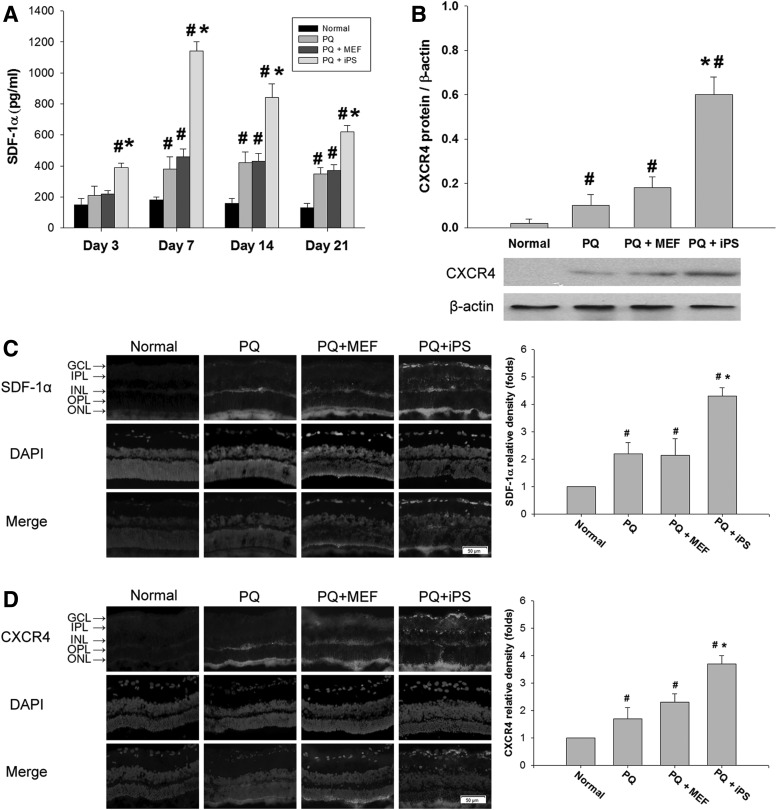

Non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation increased SDF-1α expression in oxidative-damaged retinas

In ELISA-based quantitative measurements, the levels of SDF-1α started to increase in the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas at day 3. The levels reached a maximum at day 7 and remained elevated on day 21. There was a statistically significant difference in the amount of SDF-1α in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas compared with MEF-treated and PQ-only retinas at days 3, 7, 14, and 21 (P<0.05, 2-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 5A). Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant increase in the expression of CXCR4 in the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas compared with the normal or MEF-treated or PQ-injected retinas at day 7 (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 5.

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on the expression of SDF-1α and CXCR4 in retinas. (A) The concentration of SDF-1α in each treatment group was quantified by ELISA at days 3, 7, 14, and 21 (N=3 in each group). (B) The expression of CXCR4 protein in retinas at day 7 was measured by western blot. Immunohistochemical staining against (C) SDF-1α and (D) CXCR4 in retinas was performed 14 days after transplantation. SDF-1α and CXCR4 immunoreactivity was significantly increased in the GCL of iPSC-treated retinas. Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. *P<0.05 compared with the “PQ” and “PQ+MEF” groups; #P<0.05 compared with the “normal” group; by 2-way ANOVA. SDF, stromal cell-derived factor.

In the iPSC-treated retinas, the intensity of SDF-1α immunoreactivity was increased throughout the retinas, especially in the GCL at day 3 (Fig. 5C). Corresponding to the upregulation of SDF-1α immunoreactivity, CXCR4 immunoreactivity was elevated in iPSC-treated retinas, with abundant fluorescence staining in the GCL (Fig. 5D). Retinal sections from the normal group showed only background fluorescence staining for CXCR4.

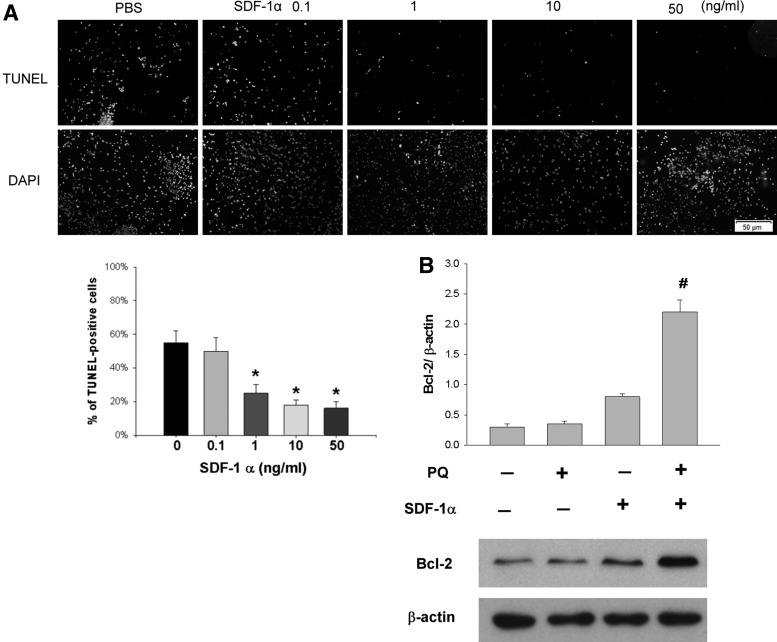

SDF-1α protects SH-SY5Y cells from oxidative stress in vitro

In the previous results, we have shown that SDF-1α could be an important mediator to modulate the beneficial effects of iPSCs. We then investigated whether SDF-1α can protect neuronal cells from oxidative damage in vitro. Treatment with 1, 10, and 50 ng/mL of SDF-1α significantly reduced PQ-induced apoptotic cell death on SH-SY5Y cells in a dose-dependent manner compared with treatment with PBS (P<0.05, 2-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

Antiapoptotic effects of SDF-1α on SH-SY5Y cells in vitro. (A) SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with 1, 10, or 50 ng/mL SDF-1α for 30 min and then exposed to 1,000 μM PQ for 24 h. Treatment with 1, 10, and 50 ng/mL of SDF-1α significantly reduced apoptotic cell death compared with treatment with PBS (N=3 in each group). *P<0.05 compared with treatment with 0 ng/mL; by 2-way ANOVA. (B) Expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 was significantly upregulated when cells were exposed to PQ and SDF-1α pretreatment. Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. #P<0.05 compared with normal control; by 1-way ANOVA. PBS, phosphate-buffered saline.

Expression of the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2 was significantly upregulated when cells were exposed to PQ and SDF-1α pretreatment (P<0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=3 in each group) (Fig. 6B).

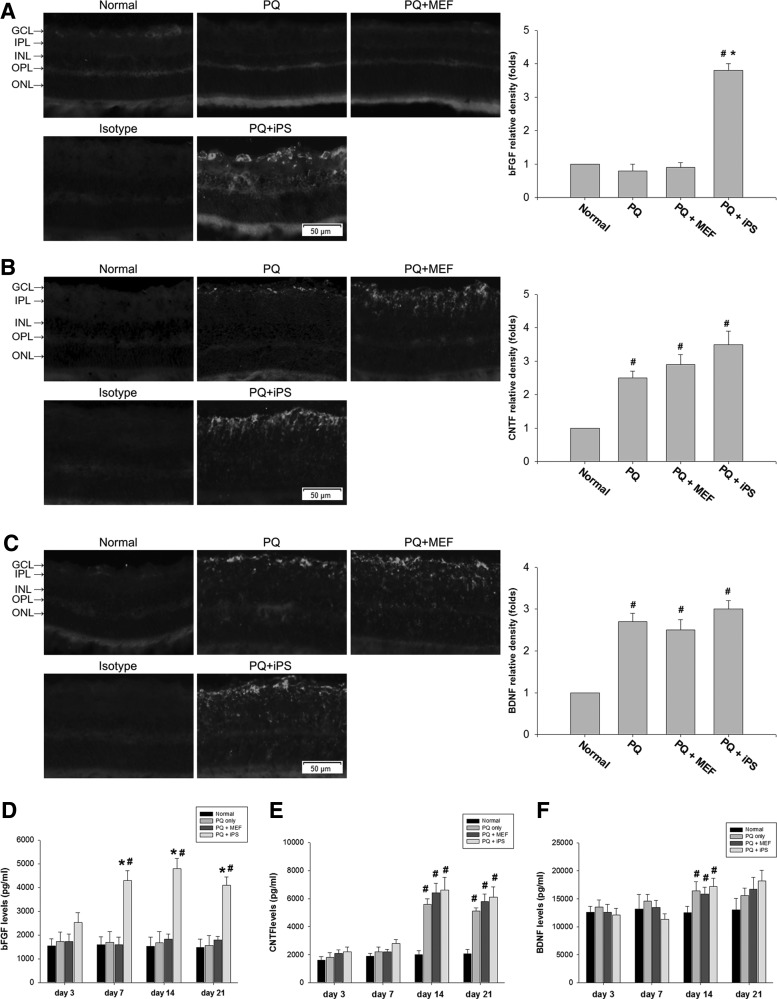

Effects of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation on the expression of bFGF, CNTF, and BDNF in the retina

Immunohistochemistry showed that bFGF immunoreactivity was significantly elevated in the GCL and INL of non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas compared with normal, PQ-injected, and MEF-treated retinas at day 14 after transplantation (Fig. 7A). Intravitreous PQ injection increased CNTF and BDNF immunoreactivity because more CNTF and BDNF immunoreactivity was found in PQ-only, MEF-treated, and non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas compared with normal retinas. However, the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas did not statistically significantly increase CNTF and BDNF immunoreactivity compared with PQ-injected and MEF-treated retinas (Fig. 7B, C).

FIG. 7.

Immunohistochemical and ELISA analyses of the neurotrophic factors BDNF, CNTF, and bFGF in the retinas of non-c-Myc iPSC–transplanted and control rats. Immunohistochemical staining against (A) bFGF, (B) CNTF, and (C) BDNF was performed 14 days after transplantation. Specimens stained with IgG isotype antibody as the primary antibody were used as negative controls. bFGF immunoreactivity was significantly elevated in the INL and GCL of non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas (N=3 in each group). The expression of (D) bFGF, (E) CNTF, and (F) BDNF in each treatment group was quantified by ELISA analysis at days 3, 7, 14, and 21. The amount of bFGF expression was significantly higher in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas than in the normal, MEF-treated, and PQ-injected retinas at 7, 14, and 21 days after transplantation (N=5 in each group). Bars show the mean±SEM. The scale bar represents 50 μm. *P<0.05 compared with the “PQ” and “PQ+MEF” groups; #P<0.05 compared with the “normal” group; by 2-way ANOVA. BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; bFGF, basic fibroblast growth factor; CNTF, ciliary neurotrophic factor.

In ELISA-based quantitative measurements, the amount of bFGF started to increase in the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas at day 3 but did not reach statistical significance compared with the MEF-treated or PQ-only retinas (P=0.09, 2-way ANOVA; N=5 in each group). However, there was significantly higher bFGF in the non-c-Myc iPSC–treated retinas than in the normal, MEF-treated, and PQ-injected retinas at 7, 14, and 21 days after transplantation (P<0.05, 2-way ANOVA; N=5 in each group) (Fig. 7D). The amount of CNTF expression was increased in non-c-Myc iPSC–treated, MEF-treated, and PQ-only retinas 14 days after transplantation. However, there were no significant differences between these groups (P>0.05, 1-way ANOVA; N=5 in each group) (Fig. 7E). Similarly, no significant difference in BDNF expression was found among normal, non-c-Myc iPSC–treated, MEF-treated, and PQ-injected retinas at 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after transplantation (P>0.05, 2-way ANOVA; N=5 in each group) (Fig. 7F).

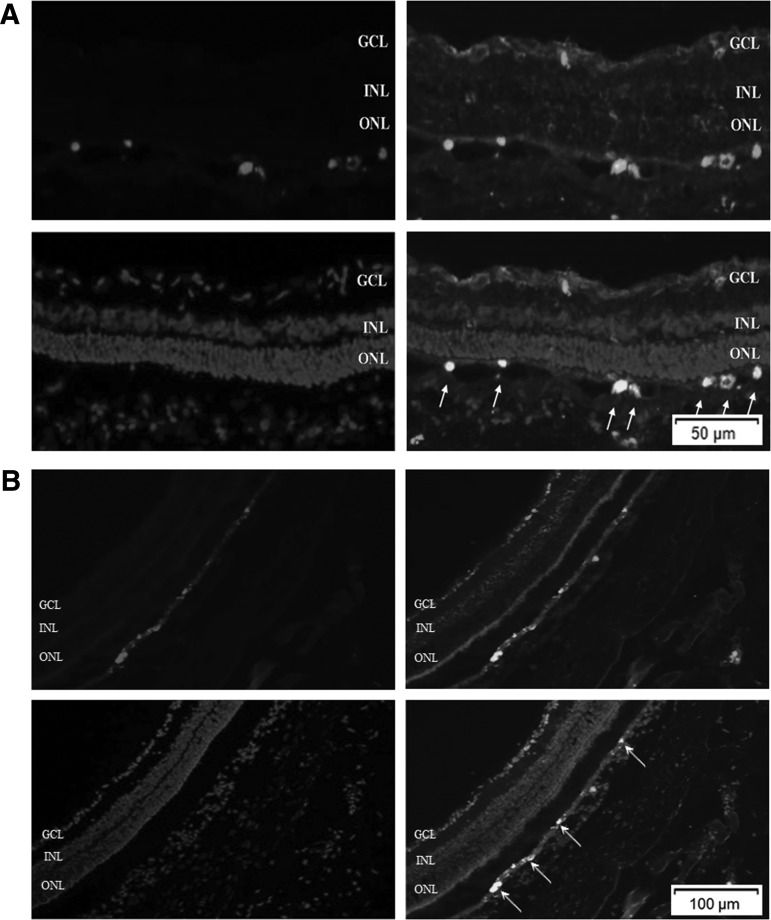

Localization of transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs

In a separate study, transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs were prelabeled with CM-DiI to track the transplanted cells. Additionally, immunohistochemistry against neurofilament-M was performed to study whether transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs could differentiate into neuronal cells. We found that many transplanted cells survived and mainly remained in the subretinal space at 14 days after transplantation. Some transplanted cells expressed neurofilament-M, indicating that these cells could differentiate into neuronal cells in the subretinal space (Fig. 8A). By 28 days after transplantation, the transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs still remained in the subretinal space. These cells could also differentiate and expressed neurofilament-M (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

Localization of transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs 14 and 28 days after transplantation. The iPSCs were prelabeled with the red fluorescent dye CM-DiI. The retinal sections were stained with rabbit polyclonal anti-neurofilament M antibody and then GFP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary antibody. DAPI was used to label the nucleus. (A) At day 14 after transplantation, many transplanted cells survived and remained in the subretinal space. Some transplanted cells showed positive staining for neurofilament-M. (B) At day 28 after transplantation, transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs still remained in the subretinal space and showed positive staining for neurofilament-M (N=3 in each group).

Assessment of tumor formation after subretinal transplantation of non-c-Myc iPSCs

No tumor formation was observed in 10 rats receiving the 3-gene iPSC transplantation by 6 months after treatment. Two rats that received the 4-gene iPSC developed tumor loci (Table 2).

Table 2.

Incidence of Tumor Formation in Recipients of 4-Gene and 3-Gene Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells and Murine Embryonic Fibroblasts 6 Months After Transplantation

| Group tumor formation | 1 month | 2 month | 3 month | 4 month | 5 month | 6 month |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPSC (4-genes) | 0/10 | 0/10 | 2/10 | 2/10 | 2/10 | 2/10 |

| Non-c-Myc iPSCs (3-genes) | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

| MEFs | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 |

iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; MEF, murine embryonic fibroblast.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that subretinal transplantation of non-c-Myc iPSCs enhanced the recovery of retinal function and improved histopathologic changes that were caused by intravitreous PQ injection. Further, non-c-Myc iPSCs increased the activities of the antioxidant enzymes SOD and catalase and decreased ROS levels in the retinas, which may be a mechanism for protecting the retinas against oxidative damage and apoptotic cell death. Remarkably, non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation increased retinal SDF-1α levels at time points preceding functional improvement, followed by enhanced bFGF expression in later periods. In vitro studies confirmed that SDF-1α contributed to the protection of retinal cells from oxidative damage. These findings indicated that the therapeutic mechanisms of non-c-Myc iPSCs were partially due to reduced retinal oxidative stress and the paracrine secretion of trophic factors SDF-1α and bFGF. Our results demonstrated the therapeutic potential of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation in treating oxidative-damage-induced retinal diseases.

It has been demonstrated that SDF-1/CXCR4 recruits bone-marrow-derived cells to neovascularization and regeneration sites in the heart, liver, and eye.22,23 However, apart from stem cell mobilization, increasing evidence has revealed that SDF-1α activates cell survival signaling and exerts antiapoptotic and neuroprotective effects.24 Wang et al. showed that intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells provides neuroprotection through the antiapoptotic effects of SDF-1α on a parkinsonian model of rats.25 Otsuka et al. showed that SDF-1 protected photoreceptor cells in a rat model of retinal detachment.26 In this study, we demonstrated that non-c-Myc iPSCs increased the production of SDF-1α in retinas early, at day 3 after transplantation. The significant increases in SDF-1α detected at an early stage after transplantation revealed the important roles of SDF-1α in angiogenesis, antiapoptosis, and the sparing of damaged retinal cells in PQ-induced retinal damage. The in vitro study confirmed that treatment with SDF-1α effectively prevented PQ-treated SH-SY5Y cells from apoptosis by upregulating the antiapoptotic protein Bcl-2. Taken together, our data provide evidence that SDF-1α plays an important regulatory role in facilitating the repair of retinal oxidative damage after iPSC transplantation.

Our results showed that transplanted non-c-Myc iPSCs survived mainly in the subretinal space and expressed a neuronal marker at day 14 after transplantation. However, the rescue of retinal function with non-c-Myc iPSC treatment was detected on day 7. These results suggested that the therapeutic benefit of non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation was not due to the differentiation of non-c-Myc iPSCs into neuronal cells. Alternatively, we found that non-c-Myc iPSC treatment significantly increased the expression of bFGF in retinas from days 7 to 21, concurrent with periods of functional improvement. These results implied that bFGF may also contribute to the functional improvements observed after iPSC transplantation. bFGF is a multifunctional protein that exerts neuroprotective and beneficial effects on functional outcomes in animal studies of oxidative damage.27,28 O'Driscoll et al. found that intravitreal bFGF injection into mice prior to light damage almost completely protected photoreceptors from light-induced degeneration.29 Xiao et al. demonstrated that bFGF protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion-induced oxidative damage under diabetic conditions.30 In a previous study, we have shown that cultured iPSCs can secrete bFGF in vitro.31 In this study, we demonstrated that the levels of bFGF did not significantly increase at day 3 but did reach significance later, at days 7, 14, and 21, while SDF-1α was upregulated early, at day 3 after iPSC transplantation. Shyu et al. demonstrated that SDF-1α exerted its neuroprotective effects by increasing the synthesis or release of neurotrophic factors in a rat model of stroke.32 Further investigation is warranted to clarify the precise mechanisms between SDF-1α and the neurotrophic factor bFGF.

ROS are known to be generated during PQ-induced retinal damage and may be pivotal mediators of the ensuing pathological complications. ROS produced in the body are scavenged by antioxidant enzymes, such as SOD and CAT. A recent study has shown that iPSCs have defense mechanisms against ROS, similar to the elevated antioxidant enzyme expression and increased strand break repair capacity of embryonic stem cells.33 In this study, we evaluated the generation of ROS in the retina by using luminol and lucigenin CL assays. Luminol detects H2O2, OH−, hypochlorite, peroxynitrite, and lipid peroxyl radicals, whereas lucigenin is particularly sensitive to superoxide radicals.34 We found that retinal-injected PQ significantly increased luminol and lucigenin CL levels and decreased the activities of SOD and CAT in the retina, whereas non-c-Myc iPSC treatment effectively decreased both the luminol and lucigenin CL levels and enhanced antioxidant enzyme activity. Moreover, we examined the oxidative damage to lipids, proteins, and DNA in the retina by staining for acrolein, nitrotyrosine, and 8-OHdG. In accordance with the decrease in ROS production, iPSC treatment also significantly decreased oxidative damage to these macromolecules and thus reduced the number of apoptotic cells in the retina. Taken together, our data indicated that non-c-Myc iPSCs are also endowed with antioxidative abilities, which contribute to the neuroprotection of retinal cells from PQ injury.

In this study, we have demonstrated that transplantation of about 100 non-c-myc iPSCs can protect the retina from oxidative damage in an animal model. Carr et al. demonstrated that transplantation of about 100 iPSC-derived RPE into the subretinal space of RCS rats is sufficient to phagocytosize photoreceptor outer segments and facilitate the short-term maintenance of photoreceptors.35 However, we only followed the efficacy of non-c-myc iPSC treatment for 28 days. Further investigation is needed to determine the long-term efficacy of non-c-myc iPSCs, including the rescue of retinal function, antioxidative effects, and sustained secretion of neuroprotective factors by the engrafted cells. In addition, the formation of teratomas has been a major problem for iPSC transplantation. Despite this concern, in the present study, we did not implant iPSCs after differentiation into other cell types. This is because PQ-induced retinal injury causes widespread damage to several types of retinal cells, including retinal ganglion cells, amacrine cells, and bipolar cells.18 Therefore, transplantation of a single type of iPSC-derived retinal cell seemed insufficient to rescue all the cell types injured in this disease. Further, other evidence has indicated that the therapeutic effects of stem cell transplantation may be attributed to paracrine effects, but not to tissue regeneration through stem cell differentiation.36,37

The oncogene c-Myc has been shown to substantially contribute to tumor formation.38,39 Dysregulated expression of c-Myc occurs in a wide range of human cancers and is often associated with poor prognosis, indicating a key role for this oncogene in tumor progression.40 Our previous study demonstrated that suppression of c-Myc expression effectively blocked teratoma formation in rats transplanted with docosahexaenoic-acid-treated iPSCs 4 months after transplantation.41 Therefore, exclusion of c-Myc would be a feasible way to reduce the incidence of tumor formation. In the present study, no tumor formation was observed in the recipients of non-c-myc iPSCs over 6 months. However, due to the safety concerns in clinical applications, nonviral vector delivery and reprogramming without pro-oncogenes would be a good strategy for future studies.

Conclusions

In this study, we demonstrated that non-c-myc iPSC transplantation attenuated the severity of the physiologic and histopathologic impairment caused by PQ-induced retinal damage. These protective effects were mediated by increased production of SDF-1α and bFGF and regulation of oxidative stress responses. Thus, non-c-Myc iPSC transplantation may be a potential resource for stem-cell-based therapy in oxidative retinal diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by research grants from a collaborative project of NTUH and VGH (VN99-07) and the Department of Health, Taipei City Government (99001-62-026).

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors have no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Beal M.F.Oxidatively modified proteins in aging and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 32:797–803, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beatty S., Koh H., Phil M., Henson D., and Boulton M.The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. Surv. Ophthalmol. 45:115–134, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkler B.S., Boulton M.E., Gottsch J.D., and Sternberg P.Oxidative damage and age-related macular degeneration. Mol. Vis. 5:32–43, 1999 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiegand R.D., Giusto N.M., Rapp L.M., and Anderson R.E.Evidence for rod outer segment lipid peroxidation following constant illumination of the rat retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 24:1433–1435, 1983 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi K., Tanabe K., Ohnuki M., et al. . Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 131:861–872, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi K., and Yamanaka S.Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 126:663–676, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kao C.L., Tai L.K., Chiou S.H., et al. . Resveratrol promotes osteogenic differentiation and protects against dexamethasone damage in murine induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 19:247–258, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirami Y., Osakada F., Takahashi K., et al. . Generation of retinal cells from mouse and human induced pluripotent stem cells. Neurosci. Lett. 458:126–131, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchholz D.E., Hikita S.T., Rowland T.J., et al. . Deviation of function retinal pigment epithelium from induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells. 27:2427–2434, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crisostomo P.R., Abarbanell A.M., Wang M., Lahm T., Wang Y., and Meldrum D.R.Embryonic stem cells attenuate myocardial dysfunction and inflammation after surgical global ischemia via paracrine actions. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295:H1726–H1735, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fang J., Chen L., Fan L., et al. . Enhanced therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cells on myocardial infarction by ischemic postconditioning through paracrine mechanisms in rats. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 51:839–847, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kinnaird T., Stabile E., Burnett M.S., et al. . Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 109:1543–1549, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhutto I.A., McLeod D.S., Merges C., Hasegawa T., and Lutty G.A.Localisation of SDF-1 and its receptor CXCR4 in retinal and choroids of aged human eyes and in eyes with age related macular degeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 90:906–910, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li M., Hale J.S., Rich J.N., Ransohoff R.M., and Lathia J.D.Chemokine CXCL12 in neurodegenerative diseases: an SOS signal for stem cell-based repair. Trends Neurosci. 35:619–628, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucia M., Ratajczak J., Reca R., Janowska-Wieczorek A., and Ratajczak M.Z.Tissue-specific muscle, neural and liver stem/progenitor cells reside in the bone marrow, respond to an SDF-1graident and are mobilized into peripheral blood during stress and tissue injury. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 32:52–57, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucia M., Reca R., Miekus K., et al. . Trafficking of normal stem cells and metastasis of cancer stem cells involve similar mechanisms: pivotal role of the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis. Stem Cells. 23:879–894, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang M., Mal N., Kiedrowski M., et al. . SDF-1 expression by mesenchymal stem cells results in trophic support of cardiac myocytes after myocardial infarction. FASEB J. 21:3197–3207, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cingolani C., Rogers B., Liu L., Kachi S., Shen J., and Campochiaro P.A.Retinal degeneration from oxidative damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 40:660–669, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H.Y., Chien Y., Chen Y.J., et al. . Reprogramming induced pluripotent stem cells in the absence of c-Myc for differentiation into hepatocyte-like cells. Biomatierals. 32:5994–6005, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee P.Y., Chien Y., Chiou G.Y., Lin C.H., Chiou C.H., and Tarng D.C.Induced pluripotent stem cells without c-Myc attenuate acute kidney injury via downregulating the signaling oxidative stress and inflammation in ischemia-reperfusion rats. Cell Transplant. 21:2569–2585, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang I.M., Yang C.H., Yang C.M., and Chen M.S.Chitosan oligosaccharides attenuates oxidative-stress related retinal degeneration in rats. PLoS One. 8:e77323, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Askari A.T., Unzek S., Popovic Z.B., et al. . Effect of stromal-cell-derived factor 1 on stem-cell homing and tissue regeneration in ischaemic cardiomyopathy. Lancet. 362:697–703, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sengupta N., Caballero S., Mames R.N., Butler J.M., Scott E.W., and Grant M.B.The role of adult bone marrow-derived stem cells in choroidal neovascularization. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44:4908–4913, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bajetto A., Barbero S., Bonavia R., et al. . Stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha induces astrocyte proliferation through the activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 pathway. J. Neurochem. 77:1226–1236, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang F., Yasuhara T., Shingo T., et al. . Intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cell exerts therapeutic effects on parkinsonian model of rats: focusing on neuroprotective effects of stromal cell-derived factor-1. BMC Neurosci. 11:52–60, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otsuka H., Arimura N., Sonoda S., et al. . Stromal cell-derived factor-1 is essential for photoreceptor cell protection in retinal detachment. Am. J. Pathol. 177:2268–2277, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faktorovich E.G., Steinberg R.H., Yasumura D., Matthes M.T., and LaVail M.M.Photoreceptor degeneration in inherited retinal dystrophy delayed by basic fibroblast growth factor. Nature. 347:83–86, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu D.Y., Cringle S., Valter K., Walsh N., Lee D., and Stone J.Photoreceptor death, trophic factor expression, retinal oxygen status, and photoreceptor function in the P23H rat. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45:2013–2019, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.O'Driscoll C., O'Connor J., O'Brien C.J., and Gotter T.G.Basic fibroblast growth factor-induced protection form light damage in the mouse retina in vivo. J. Neurochem. 105:524–536, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xiao J., Lv Y., Lin S., et al. . Cardiac protection by basic fibroblast growth factor from ischemia/reperfusion-induced injury in diabetic rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 33:444–449, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fang I.M., Yang C.M., Yang C.H., Chiou S.H., and Chen M.S.Transplantation of induced pluripotent stem cells without C-Myc attenuates retinal ischemia and reperfusion injury in rats. Exp. Eye Res. 113:49–59, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shyu W.C., Lin S.Z., Yen P.S., et al. . Stromal cell-derived factor-1 alpha promotes neuroprotection, angiogenesis, and mobilization/homing of bone marrow-derived cells in stroke rats. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 324:834–849, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Armstrong L., Tilgner K., Saretzki G., et al. . Human induced pluripotent stem cell lines show stress defense mechanisms and mitochondrial regulation similar to those of human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells. 28:661–673, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ozkan E., Yardimci S., Dulundu E., et al. . Protective potential of montelukast against hepatic ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. J. Surg. Res. 159:588–594, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carr A.J., Vugler A.A., Hikita S.T., et al. . Protective effects of human iPS-derived retinal pigment epithelium cell transplantation in the retinal dystrophic rat. PLoS One. 4:e8152, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gnecchi M., He H., Liang O.D., et al. . Paracrine action accounts for marked protection of ischemic heart by Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cells. Nat. Med. 11:367–368, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li L.F., Liu Y.Y., Yang C.T., et al. . Improvement of ventilator-induced lung injury by IPS cell-derived conditioned medium via inhibition of PI3K/Akt pathway and IP-10-dependent paracrine regulation. Biomaterials. 34:78–91, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakagawa M., Koyanagi M., Tanabe K., et al. . Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells without Myc from mouse and human fibroblasts. Nat. Biotechnol. 26:101–106, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nakagawa M., Takizawa N., Marita M., Ichisaka T., and Yamanaka S.Promotion of direct reprogramming by transformation-deficient Myc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 107:14152–14157, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelengaris S., Khan M., and Evan G.c-Myc: More than just a matter of life and death. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2:764–776, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang Y.L., Chen S.J., Kao C.L., et al. . Docosahexaenoic acid promotes dopaminergic differentiation in induced pluripotent stem cells and inhibits teratoma formation in rats with parkinson-like pathology. Cell Transplant. 21:313–332, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]