Abstract

Recently, Euro et al. [Biochem. 47, 3185 (2008)] have reported titration data for seven of nine FeS redox centers of complex I from E. coli. There is a significant uncertainty in the assignment of the titration data. Four of the titration curves were assigned to N1a, N1b, N6b, and N2 centers; one curve either to N3 or N7; one more either to N4 or N5; and the last one denoted Nx could not be assigned at all. In addition, the assignment of the titration data to N6b/N6a pair is also uncertain. In this paper, using our calculated interaction energies [Couch et al. BBA 1787, 1266 (2009)], we perform statistical analysis of these data, considering a variety of possible assignments, find the best fit, and determine the intrinsic redox potentials of the centers. The intrinsic potentials could be determined with uncertainty of less than ±10 mV at 95% confidence level for best fit assignments. We also find that the best agreement between theoretical and experimental titration curves is obtained with the N6b-N2 interaction equal to 71±14 or 96±26 mV depending on the N6b/N6a titration data assignment, which is stronger than was expected and may indicate a close distance of N2 center to the membrane surface.

Introduction

NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase, or respiratory complex I, is an integral transmembrane protein found in mitochondria and respiring bacteria [1–4]. It serves as the initial electron donor to the electron transport chain by oxidizing NADH and reducing ubiquinone. Complex I utilizes energy from this reaction to translocate four protons across the mitochondrial membrane generating, in part, the electrochemical gradient necessary for ATP production [3–5]. Recently, first structural information has become available for the enzyme from T. thermophilus [6].

The transfer of electrons in complex I occurs over a distance of approximately 90 Å [6], and involves flavin mononucleotide (FMN) and eight FeS clusters. Six [4Fe-4S] clusters (N3, N4, N5, N6a, N6b, N2) and one [2Fe-2S] cluster (N1b) comprise a “chain” of cofactors spanning the hydrophilic part of the enzyme1. One [2Fe-2S] cluster (N1a) is conserved among species, but is offset from the main chain of cofactors, and its function is still unclear. Some bacterial enzymes also contain an additional [4Fe-4S] cluster (N7) which is not present in the eukaryotic form of complex I and due to its large distance from any of the other cofactors is not thought to participate in the electron transfer process [6]. NADH, a two-electron donor, initially passes both electrons to FMN, from FMN electrons enter the main chain of FeS clusters leading to the quinone binding site (FMN→N3–N1b–N4–N5–N6a–N6b–N2 → Q).

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy has been used to study the redox behavior of individual FeS clusters of the enzyme [1, 9]. A number of groups have reported spectroscopic parameters (g-values) and redox properties (midpoint reduction potentials, Emi) for individual FeS centers [10–14]. The unambiguous assignment of spectra to individual FeS clusters, however, has been difficult due to the similarity of the g-values for certain clusters, the electrostatic interaction between the redox centers, and the relatively similar midpoint reduction potentials (most of the central FeS clusters have long been considered equipotential).

Due to electrostatic interactions of the redox centers, their intrinsic redox potentials are shifted depending on the redox state of the neighboring centers. This dependence can be expressed as follows:

| (1) |

where Emi are the intrinsic redox potentials of the centers, defined as the potential of center i when all centers are oxidized, and is the shifted potential resulting from the interaction with all other centers j; positive Δij is the electrostatic repulsion energy between i and j. The occupation numbers nj are 0 or 1 for oxidized and reduced centers, respectively. Clearly, the interpretation of the titration data depends on the magnitudes of electrostatic interactions Δij. If neither intrinsic potentials nor the interaction energies are known, the interpretation of the titration data can present a significant challenge, unless of course the interaction of a particular center is small, and its redox potential is significantly different from all others. It is the intrinsic potentials that determine the character of the electron transport along the chain, and not the apparent potentials2 that manifest in titration experiments. The intrinsic potentials are not directly observable in a strongly interacting system and can be only obtained from the analysis such as presented in this paper.

Recently, Euro et al. [9] have collected titration data for seven of nine FeS redox centers of complex I from E. coli (two centers remained “invisible”). As with EPR spectra, there is significant uncertainty in the assignment of the titration data. Four of the titration curves were assigned to N1a, N1b, N6b, and N2; one curve either to N3 or N7; one more either to N4 or N5; and the last one denoted Nx could not be assigned at all. In addition, the assignment of the titration data to N6b/N6a pair can also be considered as uncertain.

Part of the problem of assigning the titration data to specific clusters is due to the uncertainty in assignment of EPR signals, which were used to collect the titration data. In particular, the current consensus with regard to assignments of N4 and N5 EPR signals has been recently challenged by Hirst and coworkers [7], who suggested that the N5 signal is in fact due to 4Fe[G]C cluster, and N4 signal is due to a cluster in NuoI subunit. These proposals have been criticized by Ohnishi and coworkers [8], thus the uncertainly with EPR spectra is yet to be settled [4].

In this paper, using our previously calculated electrostatic interaction energies of redox centers in complex I [15], we perform a statistical analysis of Euro’s et al. data, considering a variety of possible assignments of the titration data to specific centers, and attempt to find the best fit of calculated and observed titration curves. The analysis permits us to essentially avoid all the uncertainties in the assignments of EPR spectra, since we attempt to fit the titration data directly to specific centers from the structure [6], in a variety of possible ways, assuming no a priory assignments (except for a few obvious ones, as in ref [9]), of the EPR signals. The analysis therefore is based on the knowledge of the structure and specific interaction energies between the clusters that we determined previously, rather than on the specific assumptions about the assignment of the EPR signals.

Out of 24 different and a priori possible assignments of the titration data, we find the best assignments that provide the best fits of the calculated and experimentally observed titration curves. The quality of each possible assignment is characterized by a parameter (goodness-of-fit) which describes quantitatively the likelihood of a given assignment; thereby the uncertainty of the assignments of titration data of ref [9], although not completely eliminated, is greatly reduced.

Given the previously calculated electrostatic interaction energies, the analysis allowed us to determine the intrinsic redox potentials of the centers, which are not directly accessible experimentally for a strongly interacting system. The intrinsic potentials could be determined with uncertainty of less than ±10 mV at 95% confidence level for best fit assignments. The best agreement between theoretical and experimental titration curves is obtained with the N6b-N2 interaction equal to 71±14 or 96±26 mV depending on the N6b/N6a titration data assignment, which is stronger than was expected, and may indicate a close distance of N2 center to the membrane surface.

Methods

The analysis is based on the procedure described by Press et al. [16], which provides a means to estimate the relative goodness-of-fit (GoF) for several competing models and to determine the confidence intervals for the optimized parameters. The models used in this study are based on the picture of nine interacting centers with unknown intrinsic potentials and known pair-wise electrostatic interactions calculated earlier [15]. The interaction energies are shown in Table S1 of Supporting Information; some of them may also be considered unknown when necessary.

Models to fit experimental data

We first assume that N6b/N6a data refer to N6b center. Then, there are three remaining experimental data sets with uncertain assignments: N3/N7, N4/N5, and Nx; these data sets will be also referred to as A, B, and C, respectively. Thus, one has four possible assignments derived from N3/N7 and N4/N5, and, for each combination, Nx can be one of three centers, namely, N3 or N7, N4 or N5, and N6a. Hence, there are a total of twelve possible assignments/models of the uncertain experimental data sets. Here we refer to them as models 1–12; each model is characterized by the assignment of data sets A, B, and C to specific centers. In the alternative assignment of N6b/N6a data to N6a center, we add another twelve models, 13–24, in which N6b is replaced with N6a.

Each model is characterized by a specific assignment and by a list of intrinsic potentials and interactions, which are optimized by fitting the given model to the experimental data. The optimal values of the parameters are found by minimizing the cumulative standard deviation, STD, of the calculated theoretical titration values from the experimental ones,

| (2) |

or, equivalently, the chi-square quantity,

| (3) |

Here, a = 1,…, Nexp enumerates experimental titration data points for all visible centers (Nexp ≈ 280); each data point corresponds to a specific medium redox potential, Ea, and the degree of reduction, yaexp, of one of the redox centers of the enzyme. σexp is the experimental uncertainty, assumed to be the same for all experimental points. The titration data were taken from seven experimental data sets, i = 1–7, shown in Figures 2, 5 (gxy components), 6, and 7 of ref [9] (these figures were scanned to generate the data files); accordingly, each experimental data point a belongs to one of these sets and therefore is characterized by the additional index i.

For a given model, theoretical value is the thermodynamic average of the occupation number of the metal center assigned to the corresponding data set i, n̅i(E = Ea;Em1…EmM), which depends on the external redox potential E and variable intrinsic redox potentials Emi (in some cases one of the interaction energies Δij could be varied as well). The average occupation numbers are calculated as follows:

| (4) |

where summations are taken over all possible values (0 or 1) of the occupation numbers {n} = (n1, n2, …, n7) and

For a given assignment, we vary the adjustable parameters and find their optimal values that minimize cumulative STD. The procedure is repeated for all possible assignments (in our case twenty four), and the models are then compared as described below.

Optimization procedure

For optimization, we used the code of ref [16] modified to enable using several titration curves as a single data set. Since there are only seven titration curves for nine centers, two centers in each model remain without any experimental data assigned to them; hence, the potentials of these two invisible centers affect the chi-square value only weakly, via their interactions with other centers. For this reason, the minimum of chi-square was so flat, and the ensuing uncertainties in these potentials were so large, that the potentials could not be determined (see Table S2 of Supporting Information). In calculations, we either kept these potentials fixed at values between −400 and −250 mV (marked by “#” sign in Table 1) or included one or both of them in the list of the parameters to be optimized. In both cases, however, the values of these potentials must be considered as not defined, therefore they are replaced by “nd” entries in Table 1 (further discussion see in Confidence limits on the potentials).

Table 1.

Optimized reduction potentials, −Emi (mV), the N6b-N2 interaction (mV), the estimated experimental uncertainty, σest, and the goodness-of-fit estimates, GoF (%, calculated with the lowest σest found for model 10), for some models studied. For a given model, the assignments of N3/N7, N4/N5, and Nx data are marked by superscripts a, b, and c, respectively; the potentials and the N6b-N2 interaction kept constant are marked by #. Models 1–12 and 13–24 assign N6b/N6a to N6b and N6a, respectively. nd, not defined (see Methods, Optimization procedure).

| model | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 16 | 22 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1a | 232 | 233 | 225 | 228 | 233 | 233 | 234 | 230 | 233 | 233 |

| N3 | 285a | 321c | nd | nd | 272a | 326c | nd# | nd | 321c | 310c |

| N1b | 270 | 274 | 253 | 259 | 247 | 279 | 276 | 241 | 274 | 255 |

| N4 | 295b | 291b | 276b | 285b | nd | nd# | 310c | nd | 292b | nd |

| N5 | nd# | nd# | 314c | nd# | 271b | 308b | 300b | 269b | nd# | 267b |

| N6a | 325c | nd | nd# | 325c | 313c | nd# | nd# | 313c | 253 | 246 |

| N6b | 220 | 188 | 220 | 220 | 220 | 219 | 219 | 220 | nd | nd |

| N2 | 207 | 199 | 206 | 207 | 208 | 207 | 207 | 208 | 203 | 203 |

| N7 | nd# | 314a | 314a | 314a | nd# | 318a | 315a | 310a | 314a | 311a |

| N6b-N2 | 68 | 75# | 73 | 68# | 64# | 72 | 72 | 65 | 93 | 99 |

| σest | 0.068 | 0.064 | 0.067 | 0.066 | 0.068 | 0.063 | 0.068 | 0.067 | 0.067 | 0.065 |

| GoF,% | 5 | 46 | 12 | 20 | 3 | 49 | 4 | 8 | 9 | 26 |

Goodness-of-fit estimates

As soon as a minimum of χ2 is found, the GoF of a given model is calculated by equations [16]

| (5) |

| (6) |

where M is the number of adjustable parameters (in our case M = 7–10), and Γ(a) is the gamma-function. The GoF is the probability that the observed experimental titration curves could be measured on a system of redox centers with the determined set of potentials minimizing χ2. Therefore GoF is a measure of “goodness” of a given model; it becomes particularly useful when the relative values of several competing models need to be compared, as in our case: we need to find the best assignment out of twenty four possible.

One problem with implementation of the above procedure is that σexp is generally speaking unknown and has to be somehow estimated from the experimental data themselves. To this end, following Press et al. [16], we compute the estimated experimental uncertainty,

| (7) |

and assume that the unknown experimental uncertainty, σexp, does not exceed σest calculated for any of the models under consideration,

| (8) |

Confidence limits on the potentials

The last step in the analysis is determination of the confidence limits, ±δEmi, on the optimized potentials individually. According to the statistical theory described in ref [16] (the case of one degree of freedom, ν = 1), they are determined as functions of the confidence level p and are calculated by the formula

| (9) |

where is the maximum value by which the chi-square calculated with perturbed potentials Emi ± δEmi may differ, at the given level of confidence, from its minimum value calculated with the unperturbed optimized potentials Emi, and Cii is the diagonal element of the covariance matrix corresponding to given center i. Matrix C is obtained in the optimization process, and is tabulated in ref [16]. For instance, and the individual potential of ith center is, with the confidence of 95.4%, within around the optimal value of Emi independently of the values of other potentials. Table S2 in Supporting Information shows for the p values used in the calculations.

As already mentioned, the potentials of two invisible centers remain undefined in each model, which results in an additional uncertainty, δ′Emi, in the potentials of their neighbors due to the interactions. If the potential of the jth center, Emj, is fixed in the optimization process, then the optimized potential of a neighboring center, i, is either shifted by Δij provided that the jth center is permanently reduced during titration, or is unaffected when the jth center is oxidized. When Emj is fixed at a value in the middle of the titration interval, we estimate δ′Emi as a half of the interaction; in other words,

| (10) |

where summation is taken over two invisible centers with fixed potentials. When Emj is fixed at −400 mV, the value in eq (10) should be also added to the potentials of the neighboring centers determined by the optimization procedure, which makes the optimized potentials more positive.

Outliers in the experimental data

The analysis is based on the assumption that the measured data points are normally distributed around their mean values. This assumption is often violated by the data points that occasionally are too far from the fitting curve predicted by the correct model [16]. A few outliers were removed from the experimental data sets (as shown in Figure 2).

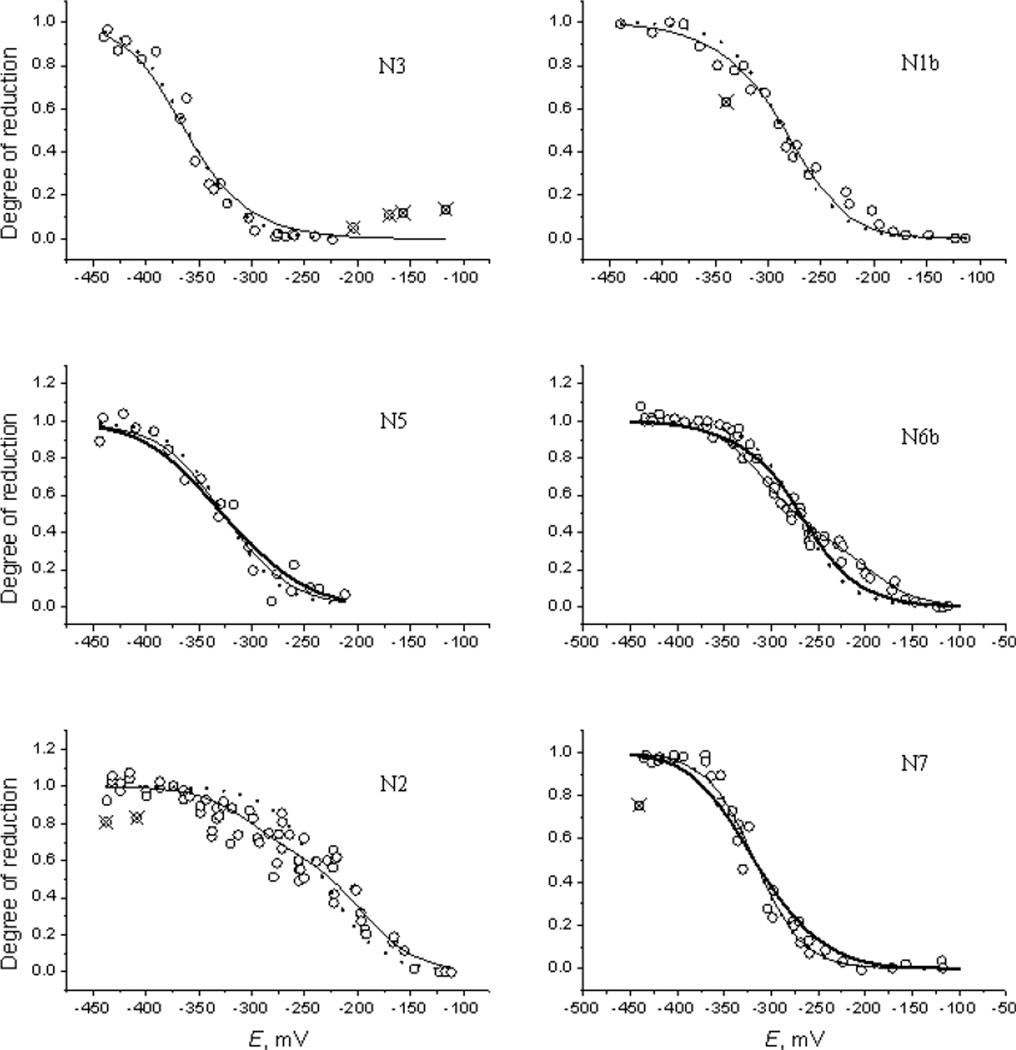

Figure 2.

Titration curves calculated with model 10 (thin full lines) and as single-electron components with optimized potentials (dotted lines). Circles, experimental data; crossed circles, outliers. Thick full line in panel N5 is the N4 titration curve of model 4. Thick full line in panel N7 is the N3 titration curve of model 2. Thick full line in panel N6b is the N6a titration curve of model 22.

Interactions as variable parameters

In the models considered the interactions between the centers, Δij, are kept constant (as calculated in ref [15]) during the potentials optimization. However, the N6b-N2 interaction calculated in ref [15] was found to be too small to provide good agreement of the calculated and measured N6b and N2 titration curves. Therefore, we either used increased fixed values (also marked by “#” in Table 1) or included this interaction in the list of optimized parameters. All the above procedures equally apply in the latter case; moreover, unlike the potentials of the invisible centers, the ensuing statistical uncertainty in the N6b-N2 interaction was reasonably small to be significant.

Results

The optimized intrinsic redox potentials for several models with relatively high GoF are shown in Table 1; the results for all considered models are given in Table S3 of Supporting Information. The models assigning Nx to N7 are not included in Table 1, despite some of them have high GoF, because this assignment was considered unlikely, following ref [9]. For a given model, the assignments of N3/N7, N4/N5 and Nx data sets are indicated by superscripts a, b, and c, respectively; the parameters kept constant during optimization are marked with the # sign. The actual potentials of the two centers for which data are unavailable (it is reminded that there are only seven experimental titration curves [9] for nine redox centers) could not be determined from the data, therefore they are replaced with the “nd” entries (see Methods, Optimization Procedure; the values used in the calculations are shown in Table S3 of Supporting Information). For example, model 10 assigns N3/N7 data to N7, N4/N5 to N5, and Nx to N3; potentials of N4 and N6a are kept constant, their actual values could not be determined; thus, seven potentials plus the N6b-N2 interaction are optimized in this model. Tables 1 and S3 also contain the estimated experimental uncertainties; the lowest value found for model 10 was used to calculate GoF shown in the bottom line of the tables.

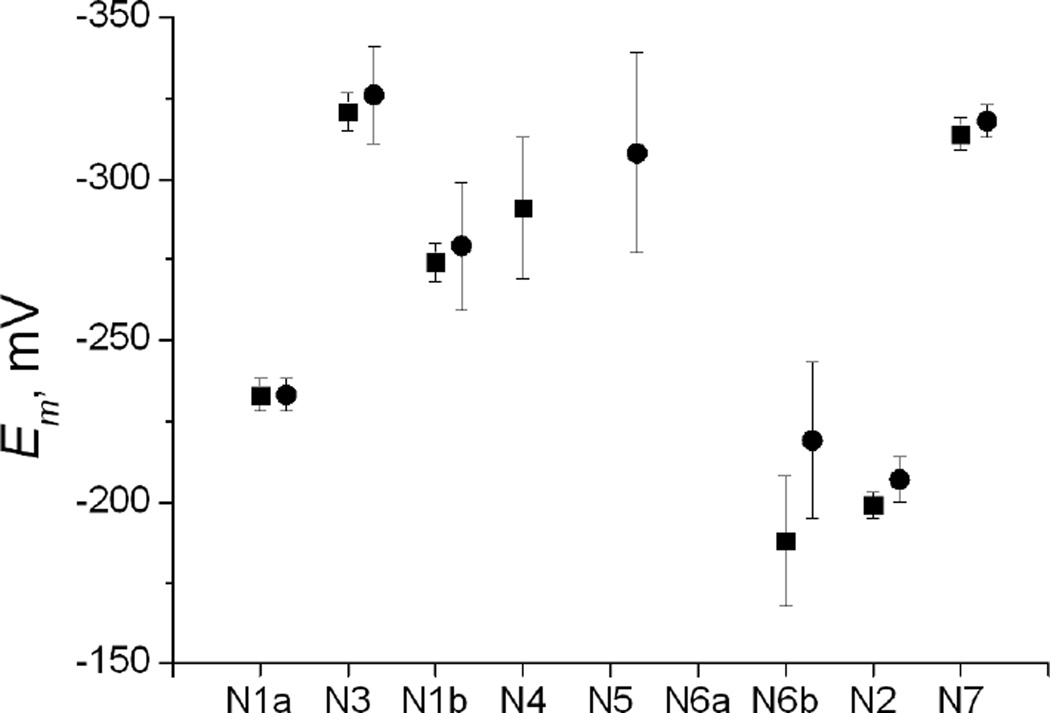

Models 4 and 10 with the highest GoF are representatives of the models with high GoF; they differ only in assigning N4/N5 to N4 or N5, respectively. The intrinsic potentials calculated in these models are shown in Figure 1. The confidence intervals of each optimized potential at p = 80–99.99% levels of confidence are shown in Table S2 of Supporting Information. Very similar confidence intervals for the potentials and the N6b-N2 interaction were obtained for all models; they are all less than 10 mV at the 95% confidence level except for N6b and N6b-N2 in models 16 and 22 (20 mV). Combining the data of Tables 1 and S2 and calculating δ′Emi by eq (10) with use of Table S1, we obtain the uncertainties of the calculated parameters at the 95% confidence level shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The optimized intrinsic potentials calculated in models 4 (squares, potentials of N5 and N6a are not defined) and 10 (circles, potentials of N4 and N6a are not defined). Error bars are calculated as described in Results.

Figure 2 shows the titration curves calculated in model 10 in comparison with both the experimental data, the single-electron approximation, and the curves from some other models (for the N1a curve and the titration curves of model 4 see Figures S1 and S2 in Supporting Information). Figure 3 shows the calculated titration curves alone for models 10 and 4 on a common panel.

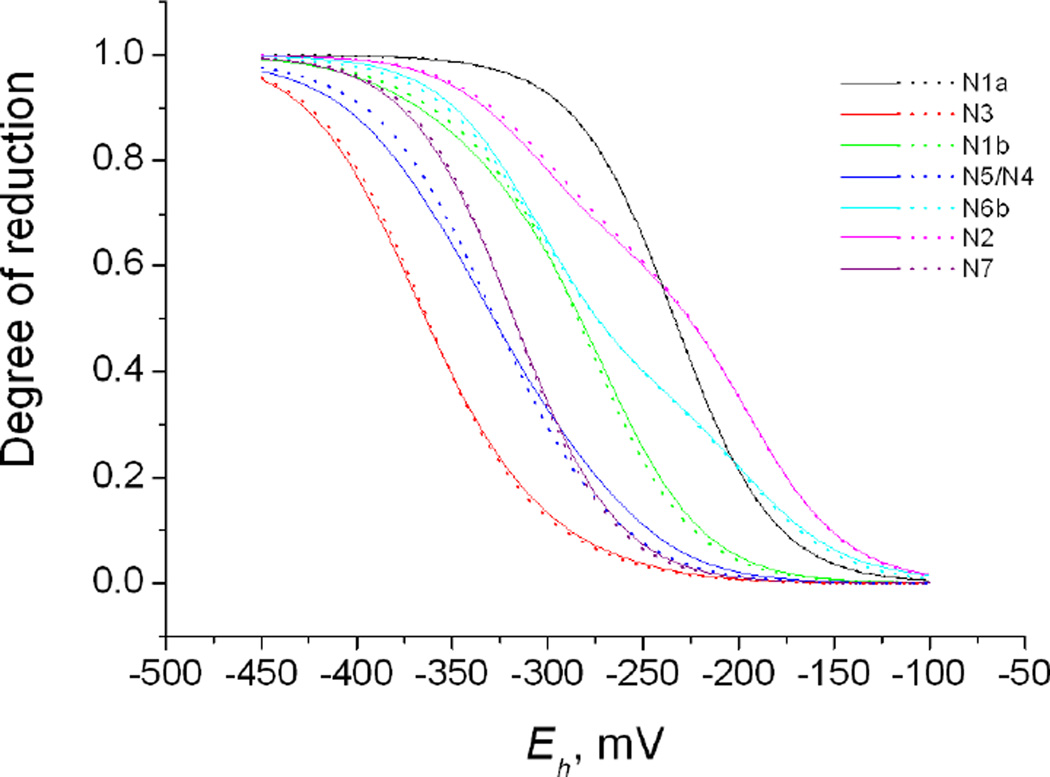

Figure 3.

Titration curves calculated in models 10 (full lines) and 4 (dotted lines).

Discussion

Goodness-of-fit estimates

The following consideration is helpful for understanding better the GoF values obtained. Suppose a model describes all experimental data within the experimental error; moreover, let’s assume that on average the deviation of theoretical predictions from the experimental data points is equal to σexp. For such a model χ2 = ν ≈ Nexp (Nexp>>1) and

| (11) |

The GoF = 100% is obtained only when theoretical predictions exactly match experimental data points, i.e. when χ2 = 0. Of course, when theoretical predictions do not exactly match the data, the goodness of theory can only be estimated when σexp is known with certainty; otherwise the calculated GoF can be taken as a quantitative measure of the relative goodness of the models considered.

For model 10, GoF = 49%; it means that on average all experimental data, with exception of outliers, deviate from the predictions of the model by our estimate of σexp. Strictly speaking, this does not necessarily mean that it is the correct model. If the actual σexp is much smaller than our estimate, then the model will have very small GoF and will have to be rejected along with other models. However, as can be seen by inspection of the data of ref [9], our estimate of σexp should not be too wrong, provided that the experimental errors are random and normally distributed3. In any case, our estimate of GoF can be taken as a measure of the relative value of the considered models.

The N6b-N2 interaction

One interesting result shown in Tables 1 and S3 is the increased interaction between the two clusters at the end of the chain, compared with that of the computational model of ref [15]. For models 1–12, assigning the N6b/N6a data to N6b, the N6b-N2 interaction is (71±14) mV, where the error bar is defined as the sum of the deviation from the arithmetic mean over all models and the statistical uncertainty given in eq (9); for models 13–24 assigning the N6b/N6a data to N6a, it is (96±26) mV. This increased N6b-N2 interaction is necessary to explain the complicated behavior of the experimental titration curves (see below). The increased interaction, compared with the computational model, which assumed a high dielectric constant of 20 for the protein, may indicate that the N6b/N2 pair is located close to the low-dielectric membrane [4, 15]. Although the membrane as such is absent in the experimental system of Euro et al, there is the hydrophobic part of the enzyme surrounded by detergent/phospholipids. The hydrophobic part itself is expected to be low dielectric, to be soluble in the membrane; the lipids may also contribute to further decreasing the dielectric constant of the hydrophobic part of the enzyme studied in the experiment.

Assignments of experimental titration curves

Inspection of Tables 1 and S3 shows that there are no strong preferences in values of GoF among the possible N4/N5 assignments. For instance, models 4 and 10, assigning N4/N5 titration data to N4 and N5, respectively, with other assignments being identical, have nearly the same GoF = 46 and 49%. Both models (4 and 10) belong to the pool of the models assigning N6b/N6a data to N6b; if N6b/N6a data are re-assigned to N6a, models 4 and 10 turn into models 16 and 22 with smaller GoF = 9 and 26%, respectively (see Table 1); hence the assignment of N6b/N6a data to N6b is preferable.

The assignment of Nx data to N3 center (models 4, 10, 16, 22) looks more preferable than any other model. For instance, among models 4, 5, and 6 assigning Nx data to N3, N5, and N6a centers, respectively, all other assignments being identical, model 4 has the highest GoF; similar trend is observed in triads (10, 11, 12), (16, 17, 18), and (22, 23, 24), see Tables 1 and S3.

Only two models (2 and 8) assign N3/N7 data to N3 center with relatively low GoF, whereas eight models assign the data to N7 with higher GoF (see Table 1); therefore, the N7 center assignment of N3/N7 data is preferable.

Shapes of titration curves

It was observed experimentally [9] that four centers titrated as single-electron (SE) components with Em = −235 (N1a), −365 (Nx), −330 (N4/N5), and −315 mV (N3/N7), whereas three other centers (N1b, N6b, and N2) titrated as sums of two one-electron components. In contrast, the present approach treats all curves as originating from the whole chain of interacting centers. The titration curves calculated for some representative models are shown in Figure 2.

Centers N1a and N7 are quite isolated from the others, and therefore they are only slightly perturbed by the interactions with neighbors (see Table S1 in Supporting Information). Consequently, their titration curves should have SE shapes. Our results confirm this expectation for N1a: the N1a titration curves in all models have the same individual standard deviation from the experimental dataset, STD = 0.050, as the SE curve (for representative model 10 the data are shown in Figure S1 of Supporting Information). The calculated intrinsic potential Em(N1a) = (−233±6) mV agrees with −235 mV given by Euro et al. It is interesting to note that weak interaction with N3 (10 mV) could manifest as small yet discernible deformation of the N1a SE shape, which did not occur in reality because N3 is mostly oxidized due to its low Em; indeed, N3 manifests either as N3/N7 or Nx, or it is invisible, in all cases being at a low potential.

The remoteness of N7 helps to assign the N3/N7 data by inspecting the titration curve. When N3/N7 is assigned to N7, which only weakly (8 mV) interacts with N4 (model 10, panel N7 in Figure 2), the calculated curve (thin line) exactly matches the experimental points and the SE curve (dotted line masked by thin line); the standard deviations of both the model 10 and SE curves from the measured dataset are STD = 0.055. In contrast, when N3/N7 is assigned to N3 (models 2 and 8), which interacts with both N1a (10 mV) and N1b (23 mV), the calculated curve appreciably declines from experiment, as shown for model 2 by thick curve on panel N7 of Figure 2; the standard deviations are STD = 0.071 and 0.065 for models 2 and 8, respectively, which are much larger than 0.055 for the SE curve (see Table S4 of Supporting Information). With the ambient potential decreasing, the titration curve of a cluster interacting with its neighbors becomes more flat compared to the SE curve, which manifests as earlier rise at the beginning of reduction and retarded saturation at the end; exactly such a behavior is demonstrated by the model 2 curve. Therefore, the assignment of N7/N3 data to N7 center appears to be more preferable.

Similar considerations can be applied to N4/N5 data. In model 10, the N5 titration curve better represents the experimental dataset than the SE one, see panel N5 in Figure 2. The model 10 curve was calculated at the potentials of invisible clusters (N4 and N6a) kept constant at −400 mV (see Table S3 of Supporting Information), so that only weak interactions with the second neighbors affected the shape of the curve, which resulted in a slight improvement of the fit with respect to the SE curve. Increasing the potentials of either N4, N6a, or both appreciably decreased the quality of the fit. In contrast, assignment of N4/N5 curve to N4 in model 4 (invisible clusters N5 and N6a) resulted in increased interaction with N1b, therefore the titration curve became essentially more flat (thick curve in panel N5 of Figure 2) with a larger STD. This fact may be considered as indication that the N4/N5 assignment to N5 looks more preferable. Comparing other pairs of models that differ only by N4/N5 assignment (e.g., 2&8, 16&22) reveal the same trend: the values of GoF are similar but STD are better for models assigning N4/N5 to N5 (see Tables S3 and S4 of Supporting Information). In any case, the above calculations have proven with certainty that the N4/N5 signal is due to a cluster apparently weakly interacting with other clusters. The one-electron character of the N4/N5 titration curve is not because of the absence of interactions, but because the neighboring centers (those with strong electrostatic interactions) do not get reduced in the experiment. So, most likely, the two invisible centers are surrounding the center responsible for the N4/N5 signal.

The N1b, N6b/N6a, and N2 titration curves demonstrate more complicated behavior. Indeed, in Figure 2 essential differences are seen between the SE curves (dotted lines) and the experimental data (circles). Our model 10 (solid lines in Figure 2) and, moreover, all other models of Table 1 (curves not shown) describe these data much better, with smaller individual standard deviations than the SE curves (see Table S4 in Supporting Information). The fits to all three datasets are very good. This result was achieved by increasing the N6b-N2 interaction from 27 mV calculated in ref [15] to 70 or 100 mV when N6b/N6a is assigned to N6b or N6a, respectively. It can be speculated that the inflated N6b-N2 interaction is compensating for protonation state changes occurring during reduction of N2. It is known that the Emi of cluster N2 is pH dependent (−60 mV/pH) [1]. Furthermore, recent X-ray crystal studies of the peripheral arm of complex I from T. thermophilus in various redox states have shown that N2 undergoes changes in its cys ligation (and hence protonation state) upon reduction [17].

Finally, we compare the calculated N6b/N6a titration curves in two pairs of models, (10, 22) and (4, 16), where the first members assign N6b/N6a to N6b and the second to N6a, other assignments being identical. Panel N6b of Figure 2 demonstrates that model 10 represents the experimental dataset much better than model 22 (similar picture is also observed for the second pair, not shown). It is noticeable that the model 10 curve successfully reproduces the kink at −250 mV caused by strong N6b-N2 interaction whereas the model 22 goes smoothly across this point. This conclusion is also supported by significant differences in individual STD, which are equal to (0.049, 0.064) and (0.046, 0.066) for the above two pairs of models, respectively (see Table S4 of Supporting Information). Thus, assignment to N6b looks more preferable.

Intrinsic midpoint potentials are important parameters determining the mechanism of electron transfer along the chain of FeS clusters. Yet, they are not directly measurable in experiment because of interaction between the clusters. Therefore, an analysis like the one presented in this paper is absolutely necessary in order to extract the intrinsic potentials from the data that depend solely on the apparent potentials.

Each model under study permits evaluation of the intrinsic potentials of visible centers with uncertainties discussed in the Methods section, Confidence limits on the potentials. In addition, model-independent potentials of visible centers N1a, N1b, and N2 can be determined by taking arithmetic average of the calculated potentials among those models in which a given center has no invisible centers next to it and, hence, its potential is only slightly affected by interactions with the invisible centers. For instance, models 2, 4, and 16 in Table 1 have the optimized N1b potentials equal to −270, −274, and −274 mV, respectively, which should be increased by half of the interaction with N5 to give −263, −267, and −267 mV (see Methods, Confidence limits on the potentials); additional models can be used from Table S3 of Supporting Information, resulting in Em(N1b) = (−265±10) mV, where the statistical uncertainty of eq (9) has been included as well. In this way, Em(N1a) shown above and Em(N2) = −205±10 mV (N6b/N6a is assigned to N6b) or −217±10 mV (N6b/N6a is assigned to N6a) have been obtained. These results can be compared with Euro’s et al. two-component potentials of −245/−320 mV (N1b) and −200/−300 mV (N2).

Euro et al. pointed out that the FeS clusters are not equipotential, rather the potentials are dispersed between −160 and −500 mV. We obtained somewhat narrower range shown in Figure 1. The N2 cluster has the highest potential in the chain, while N3 has the lowest potential. The entire profile of the intrinsic potentials along the chain qualitatively resembles the ‘roller coaster’, although not as perfect as envisioned in ref. [4]; in any case the chain is clearly far from being equipotential. This type of electron transport chains with alternating potentials [18, 19] appear to be able to accomplish perfectly well their function [20].

The uncertainties shown by error bars in Figure 1 are rather small for N1a and N7, which are distant from N4 and N6a; on the contrary, potentials of other centers are more spread out due to interactions with the centers whose potentials could not be defined because of the lack of the respective titration data. We should also note that the absence of experimental data for two unresolved clusters remains the largest source of uncertainty in the optimized potentials, which influences the quality of the fits as well.

Since we now know both the intrinsic potentials and the interaction energies, we can predict the redox state of the chain depending on the ambient redox potential. The curves in Figure 3 show the succession in which the FeS clusters get reduced with the decreasing ambient potential. The two best models, which differ only by the N4/N5 data assignment, are practically indistinguishable by their titration patterns except, perhaps, for N4 and N5. The two invisible centers are most likely located in the middle of the chain. One possible reason for them not to be seen is that they have low apparent potentials and, therefore, are not reduced in the experiment. There maybe of course other reasons too, such as very fast spin relaxation.

Conclusions

Our analysis supports the following assignments of the titration data of Euro et al [9]: N3/N7 titration curve is due to N7 cluster, N4/N5 curve is due to N5, Nx curve is due to N3, and N6b/N6a data refer to N6b.

The titration data are successfully described in terms of a chain of interacting clusters with interactions calculated in ref [15] except for the N6b-N2 interaction, which has to be increased by three to four times. This result is independent of the assignments. The increased interaction, compared with the computational model that assumed a high dielectric constant of 20 for the protein, may indicate that the pair N2-N6b is located close to the low dielectric membrane, as predicted by the model of ref [15].

In the best cases, the intrinsic potentials could be determined with a rather small (less than 10 mV) statistical uncertainty, the major source of uncertainties in the potentials being the lack of data for two unresolved clusters.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the Russian Foundation for Fundamental Research (08-03-00094-a) to ESM and by grants from NSF (PHY 0646273) and NIH (GM54052) to AAS.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

In this paper the symbols N1a, N3, N4, etc, are used only as labels for redox centers, as adopted in Ref. [6]. These labels are not to be mixed with the same names of EPR signals used in the literature, see discussion of this potentially confusing point in Refs. [7, 8].

The apparent potential is the external redox potential at which a given center gets reduced.

In practice, non-normal distributions manifest themselves via the appearance of outliers, i.e., data points with abnormally large deviations from the mean. Such points marked by crosses are seen in Figure 2. The outliers were not included in the calculations.

References

- 1.Ohnishi T. Iron-sulfur clusters/semiquinones in complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1364:186–206. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00027-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vinogradov AD. NADH/NAD+ interaction with NADH: Ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1777:729–734. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zickermann V, Kerscher S, Zwicker K, Tocilescu MA, Radermacher M, Brandt U. Architecture of complex I and its implications for electron transfer and proton pumping. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1787:574–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirst J. Towards the molecular mechanism of respiratory complex I. Biochem. J. 2010;425:325–339. doi: 10.1042/BJ20091382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirst J. Energy transduction by respiratory complex I - an evaluation of current knowledge. Biochem. Soc. Transact. 2005;33:525–529. doi: 10.1042/BST0330525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sazanov LA, Hinchliffe P. Structure of the hydrophilic domain of respiratory complex I from Thermus thermophilis. Science. 2006;311:1430–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.1123809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yakovlev G, Reda T, Hirst J. Reevaluating the relationship between EPR spectra and enzyme structure for the iron-sulfur clusters in NADH:quinone oxidoreductase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:12720–12725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705593104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohnishi T, Nakamaru-Ogiso E. Were there any "misassignments" among iron-sulfur clusters N4, N5 and N6b in NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (complex I)?". BBA - Bioenergetics. 2008;1777:703–710. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Euro L, Bloch DA, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI, Verkhovskaya ML. Electrostatic interactions between FeS clusters in NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) from Escherichia coli. Biochem. 2008;47:3185–3193. doi: 10.1021/bi702063t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnamoorthy G, Hinkle P. Studies on the electron transfer pathway, topography of iron-sulfur centers, and site of coupling in NADH-Q oxidoreductase. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:17566–17575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Magnitsky S, Sled VD, Hagerhall C, Grivennikova VG, Ohnishi T, Vinogradov AD, Burbaev DS. EPR characterization of ubisemiquinones and iron–sulfur cluster N2, central components of the energy coupling in the NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I). in situ. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 2002;34:193–208. doi: 10.1023/a:1016083419979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verkhovskaya ML, Belevich N, Euro L, Wikstrom M, Verkhovsky MI. Real-time electron transfer in respiratory complex I. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008;105:3763–3767. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711249105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reda T, Barker CD, Hirst J. Reduction of the iron-sulfur clusters in mitochondrial NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) by Eu-II-DTPA, a very low potential reductant. Biochemistry. 2008;47:8885–8893. doi: 10.1021/bi800437g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamaru-Ogiso E, Matsuno-Yagi A, Yoshikawa S, Yagi T, Ohnishi T. Iron-sulfur cluster N5 is coordinated by an HXXXCXXCXXXXXC motif in the NuoG subunit of Escherichia coli NADH:quinone oxidoreductase (complex I) J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:25979–25987. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804015200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Couch VA, Medvedev ES, Stuchebrukhov AA. Electrostatics of the FeS clusters in respiratory complex I. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Bioenergetics. 2009;1787:1266–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Press WH, Teukolsky SA, Vetterling WT, Flannery BP. Numerical Recipes in FORTRAN. 2nd ed. Chap.15. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berrisford JM, Sazanov LA. Structural basis for the mechanism of respiratory complex I. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:29773–29783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen I-P, Mathis P, Koepke J, Michel H. Uphill electron transfer in the tetraheme cytochrome subunit of the Rhodopseudomonas viridis photosynthetic reaction center: Evidence from site-directed mutagenesis. Biochem. 2000;39:3592–3602. doi: 10.1021/bi992443p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alric J, Lavergne J, Rappaport F, Vermeglio A, Matsuura K, Shimada K, Nagashima KVP. Kinetic performance and energy profile in a roller coaster electron transfer chain: a study of modified tetraheme-reaction center constructs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:4136–4145. doi: 10.1021/ja058131t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Page CC, Moser CC, Dutton PL. Mechanism for electron transfer within and between proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2003;7:551–556. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.