Abstract

Purpose

CALGB 19802, a phase II study, evaluated whether dose intensification of daunorubicin and cytarabine could improve disease-free survival (DFS) of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and whether high-dose systemic and intrathecal methotrexate could replace cranial radiotherapy for central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis.

Patients and Methods

One hundred sixty-one eligible, previously untreated patients age 16–82 years (median, 40 years) were enrolled; 33 (20%) were ≥60years old.

Results

One hundred twenty-eight patients (80%) achieved a complete remission (CR). Dose intensification of daunorubicin and cytarabine was feasible. With a median follow-up of 10.4 years for surviving patients, 5-year DFS was 25% (95% CI, 18–33%) and overall survival (OS) was 30% (95% CI, 23–37%). Patients <60 years who received the 80 mg/m2 dose of daunorubicin had a DFS of 33% (22–44%) and OS of 39% (29–49%) at 5 years. Eighty-four (52%) patients relapsed, including nine (6%) with isolated CNS relapses. Omission of cranial irradiation did not result in higher than historical CNS relapse rates.

Conclusion

Intensive systemic, oral, and intrathecal methotrexate dosing permitted omission of CNS irradiation. This intensive approach using higher doses of daunorubicin and cytarabine failed to result in an overall improvement in DFS or OS compared with historical CALGB studies. Future therapeutic strategies for adults with ALL should be tailored to specific age and molecular genetic subsets.

INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, attempts to improve survival of adults with ALL have focused on the role of early dose intensification to eradicate minimal residual disease and prevent the emergence of drug resistant sub-clones1–7. Several trials have explored the role of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation performed in first remission8,9. Others have tested the efficacy of dose intensification of several of the drugs that are standard components of ALL regimens4,10–13. Todeschini et al13 used high doses of daunorubicin (cumulative dose of 270 mg/m2) during induction and high-dose cytarabine during post-remission consolidation and reported a high complete remission (CR) rate of 93% and an estimated 6-year event-free survival of 55% in a small series of adults with ALL, 14–71 years old.

Effective central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis is also an essential component of therapy. Pediatric ALL regimens have tested a variety of approaches to reduce CNS relapses while minimizing the long-term toxicities of CNS-directed therapies. The substitution of high doses of systemic methotrexate and cytarabine for cranial irradiation, given in combination with intrathecal (IT) methotrexate and/or cytarabine during post-remission therapy, has been shown to be feasible and safe in both children and adults with ALL and may result in lower cumulative neurotoxicity4,12,14–17. Others have suggested that the combination of oral, intravenous, and IT methotrexate administered to achieve prolonged serum levels can result in effective CNS prophylaxis18–20.

CALGB study 19802 was designed to test the hypothesis that dose intensification of daunorubicin during induction and of cytarabine during the first weeks of post-remission treatment would result in rapid leukemia cytoreduction, lead to high CR rates, and improve disease-free survival (DFS) by preventing the emergence of drug resistant leukemia clones that could lead to relapse. The second objective was to determine whether administration of high dose intravenous, oral, and IT methotrexate could result in prolonged serum exposure and safely and effectively replace the cranial irradiation which had been used for CNS prophylaxis in all previous CALGB regimens.

METHODS

Patients

From January 1999 through January 2001, 163 adults (≥ 16 years old) with untreated ALL were enrolled on CALGB 19802. No prior treatment for ALL, including corticosteroids, was allowed with the exception of emergency treatment for hyperleukocytosis with hydroxyurea and/or leukapheresis, or a single dose of cranial irradiation for CNS leukostasis. Patients with a mature B-cell (Burkitt) immunophenotype were not eligible for this study

Chemotherapy

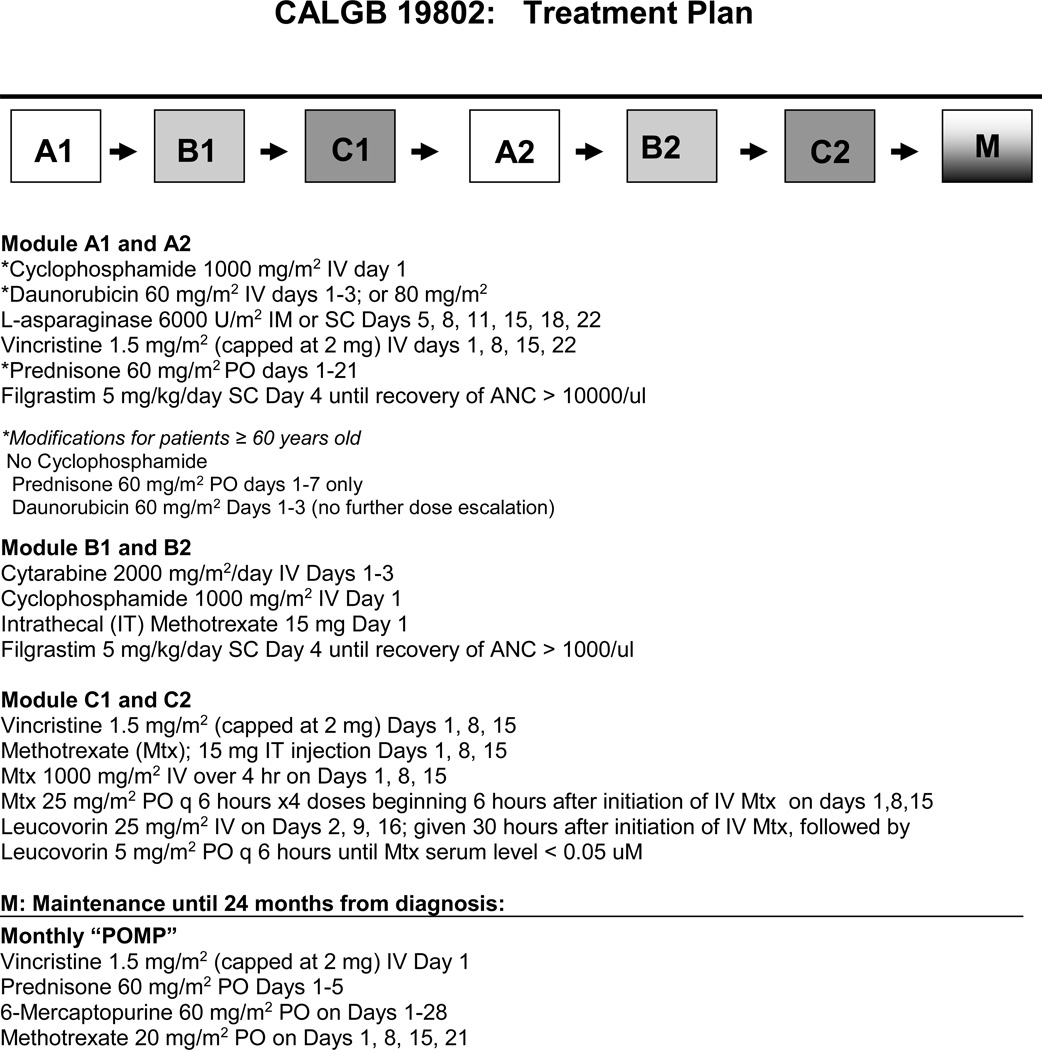

CALGB 19802 treatment consisted of six monthly modules of intensive therapy (Modules: A1, B1, C1, A2, B2, C2) followed by 18 months of maintenance therapy (Figure 1). Planned dose intensification of daunorubicin occurred during module A1 and A2, high dose cytarabine was given during module B1 and B2, and high dose intravenous methotrexate, oral methotrexate and IT methotrexate were given during both C modules. IT therapy was also administered during each of the B modules as detailed in Table 1. Previously, the CALGB used three daily doses of 45 mg/m2 of daunorubicin for patients < 60 years old and 30 mg/m2 for patients ≥ 60 years old. In this study we escalated the daunorubicin dose in cohorts to 60 mg/m2 IV on days 1–3 in the first 50 patients and then to 80 mg/m2 on days 1–3 for all subsequent patients ≤ 60 years old. Patients older than 60 years received only the 60 mg/m2 dose. All treatment ended 24 months after diagnosis. Patients with high-risk cytogenetics, including the t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) and t(4;11)(q21;q23), were recommended to receive an allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant soon after achievement of remission

Figure 1. Treatment plan.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| N=161 | Median (Range) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 40 yrs (16–82) | |

| Presenting WBC (×103/ul) | 10.6 (0.5–348.5) | |

| N (%) | ||

| Age Distribution | ||

| 16–19 yrs | 13 (8) | |

| 20–29 yrs | 34 (21) | |

| 30–39 yrs | 30 (19) | |

| 40–59 yrs | 51 (32) | |

| ≥60 yrs | 33 (21) | |

| Male Gender | 98 (61) | |

| Performance Status | ||

| 0–1 | 131 (84) | |

| ≥ 2 | 25 (16) | |

| Immunophenotype, evaluable | 124 | |

| Precursor B-Cell | 97 (78) | |

| Precursor T-Cell | 19 (15) | |

| Ambiguous Linage | 8 (6) | |

| Cytogenetics, evaluable | 98 (61) | |

| Favorable | 11 (11) | |

| Intermediate | 31 (32) | |

| Unfavorable (excluding Ph+) Ph+ ALL |

17 (17) 31 (32) |

|

| Prognostically unclassifiable | 8 (8) | |

| Daunorubicin Dose | ||

| 60 mg/m2 × 3 | 72 (45) | |

| ≥ 60 yrs | 33 (21) | |

| < 60 yrs | 39 (24) | |

| 80 mg/m2 ×3 | ||

| <60 yrs | 89 (55) | |

Statistical analysis

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the CR and DFS rates for this regimen as well as the rates of adverse events. The null hypothesis was that the CR rate is ≤ 70% versus the alternative hypothesis that the CR rate is ≥ 80%. DFS was measured from the date of CR to the date of relapse or death. The precision for the 5-year DFS estimate was expected to be ± 10%. Exact 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for the CR rate were computed based on the binomial distribution. Tests of CR rates between groups were performed using Fisher’s exact test. Survival estimates with 95% CI were computed using the product-limit (Kaplan-Meier) method. Tests for differences in survival distributions between groups were performed using the Score (log-rank) statistic. SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all statistical analyses and S-Plus 7.0 (Insightful Corporation, Seattle WA) was used to generate the survival plots. The statistical analyses were completed on data as of February 22, 2012.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The median age was 40 years (range, 16–82). There was no upper limit on age, and 33 patients (20%) were ≥ 60 years old.

Pretreatment cytogenetic analyses were performed by CALGB-approved institutional cytogenetic laboratories on CALGB 8461, a prospective cytogenetic companion study and centrally reviewed (KM, CDB). Of the 163 enrolled patients, two were found to have a rearrangement involving 8q24 (MYC), consistent with Burkitt-type ALL, and were thus ineligible for treatment on this study; 63 (39%) cases were not submitted or not evaluable. Thus, 98 (61%) patients were further characterized21,22. Forty-eight (49%) were classified as cytogenetic high risk defined as: t(9;22)(q34;q11.2) or variants (n = 31); t(4;11)(q21;q23) or other balanced translocation involving band 11q23 (n = 7); −7 (n = 1), +8 (n = 2), and hypodiploidy with a chromosome number ≤ 43 (n = 4). Thirty-one (32%) were intermediate risk [normal karyotype (n = 18); abnormalities of 9p (n = 4); high hyperdiploidy with a chromosome number ≥ 50 (n = 6), excluding near-tetraploidy; del(13q) (n = 2); and der(19)t(1;19) (n =1)]. Only 11 (11%) patients had a favorable karyotype [abnormalities involving 14q11 (n= 5); deletions and translocations involving 12p (n = 4); and balanced rearrangements involving 7p14–15 and 7q34–36 (n = 2)]. Eight patients (8%) had cytogenetic abnormalities with unknown prognostic significance: three had 14q32 abnormalities other than the t(8;14)(q24;q32), and five patients had a variety of other aberrations.

Remission Induction

One hundred sixty-one patients were eligible and evaluable for response. One hundred twenty-eight (80%; 95% CI, 72–85%) achieved a CR (Table 2). There were 16 (10%) treatment-related deaths during induction; only one of these patients was < 30 years old (2%).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics and outcomes

| n (%) | Response Rate CR (%) (95% CI) |

DFS at 5 years (95%CI) |

OS at 5 years (95%CI) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 161 | 128 (80%) (72,85%) | 25% (18,33%) | 30% (23,37%) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 98 (61%) | 81 (83%) (74,90%) | 27% (18,38%) | 31% (22,40%) | |

| Female | 63 (39%) | 47 (75%) (62,85%) | 21% (11,34%) | 29% (18–40%) | |

| Age | |||||

| 16–19 | 13 (8 %) | 11 (85%) (55,98%) | 27% (7,54%) | 38% (14,63%) | |

| 20–29 | 34 (21%) | 32 (94%) (80,99%) | 35% (18,51%) | 45% (27,61%) | |

| 30–39 | 30 (19%) | 25 (83%) (65,94%) | 24% (10,42%) | 33% (18,50%) | |

| 40–59 | 51 (32%) | 40 (78%) (65,89%) | 25% (13,39%) | 31% (19,44%) | |

| ≥ 60 | 33 (21%) | 20 (61%) (42,77%) | 10% (2,27%) | 6% (1,18%) | |

| Age/Daunorubicin | |||||

| <60 yrs | |||||

| 60 mg/m2 | 39 (24%) | 36 (92%) (79,98%) | 18% (7,32%) | 29% (16,44%) | |

| 80 mg/m2 | 89 (55%) | 72 (81%) (71,89%) | 33% (22,44%) | 39% (29,49%) | |

| ≥ 60 yrs | |||||

| 60 mg/m2 | 33 (21%) | 20 (61%) (42,77%) | 10% (2,27%) | 6% (1,18%) | |

| Cytogenetics | |||||

| Favorable | 11 (11%) | 11 (100%) (72,100%) | 45% (17,71%) | 82% (45,95%) | |

| Intermediate | 31 (32%) | 27 (87%) (70,96%) | 20% (8,37%) | 24% (11,40%) | |

| Poor (Ph negative) | 17 (17%) | 13 (76%) (50,93%) | 23% (6,47%) | 18% (4,38%) | |

| Ph positive | 31 (32%) | 19 (61%) (42,78%) | 26% (10,47%) | 23% (10,38%) | |

| Prognostically Unclassifiable | 8 (8%) | 6 (75%) (35,97%) | 33% (5,68%) | 38% (9,67%) | |

| Missing | 63 | ||||

| Immunophenotype | |||||

| Precursor B | 97 (78%) | 79 (81%) (71,88%) | 23% (15,33%) | 25% (17,34%) | |

| Precursor T | 19 (15%) | 17 (89%) (67,99%) | 35% (14,57%) | 53% (29,72%) | |

| Ambiguous | 8 (6%) | 6 (75%) (35,97%) | 17% (0.1,52%) | 12% (1,42%) | |

| Missing | 37 | ||||

| WBC | |||||

| ≤ 30 K | 114 (72%) | 94 (82%) (73,88%) | 26% (18,35%) | 31% (23,40%) | |

| > 30 K | 45 (28%) | 33 (73%) (58,85%) | 20% (8, 35%) | 26% (14,39%) | |

| Missing | 2 | ||||

Toxicity

All patients who began treatment were evaluated for toxicity. Twenty-one patients (13%) died of treatment-related complications; 16 during induction therapy and five during post-remission treatment. Of note, there was no significant cardiomyopathy reported for any patient treated at the daunorubicin 80 mg/m2 dose level. Life-threatening (grade 4) mucosal toxicities were reported in five patients during treatment, four of whom were < 60 years old and had received the 80 mg/m2 doses of daunorubicin. Grade 4 ataxia attributed to high dose cytarabine was reported in two patients, both of whom were < 60 years of age. Grade 3 or 4 mucositis or stomatitis were rarely reported during the C1 and C2 treatment modules; however, grade 3–4 cytopenias were reported in approximately 68% of the patients who had mean serum methotrexate levels higher than 2 µM in contrast to 38% of patients with lower methotrexate levels (p=0.004)

Disease-free and Overall Survival

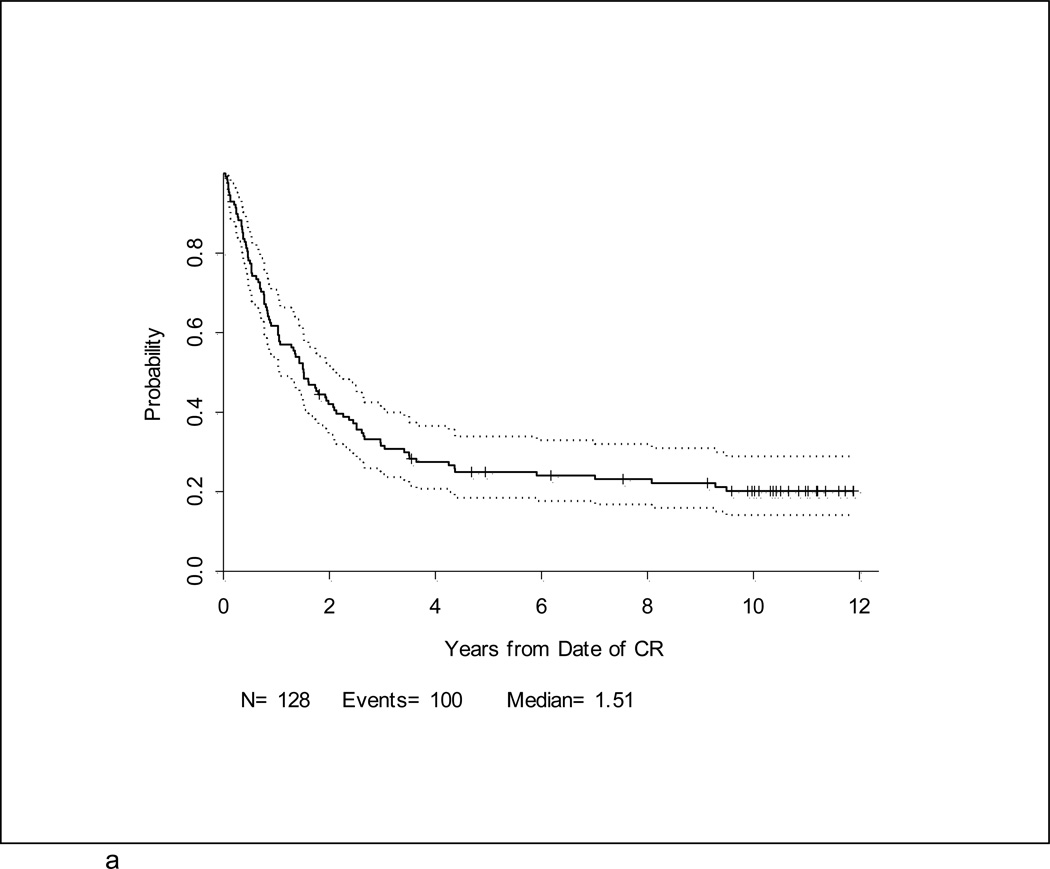

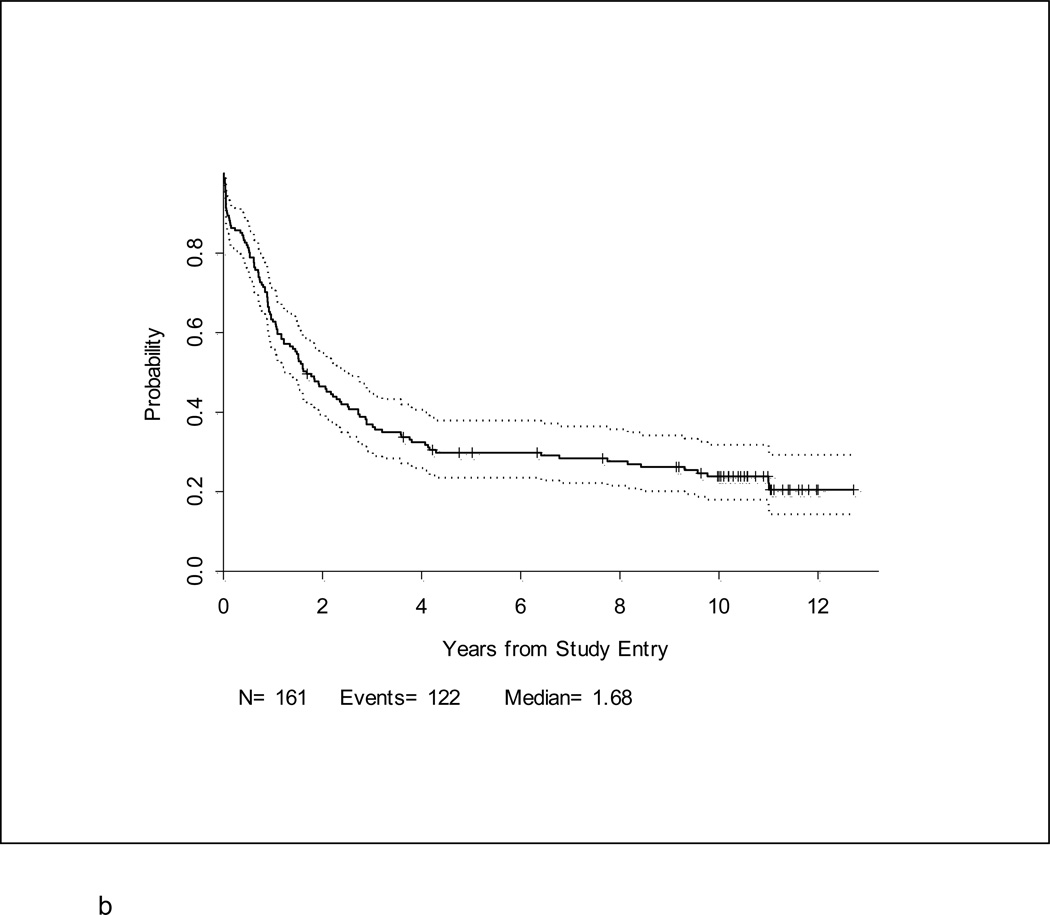

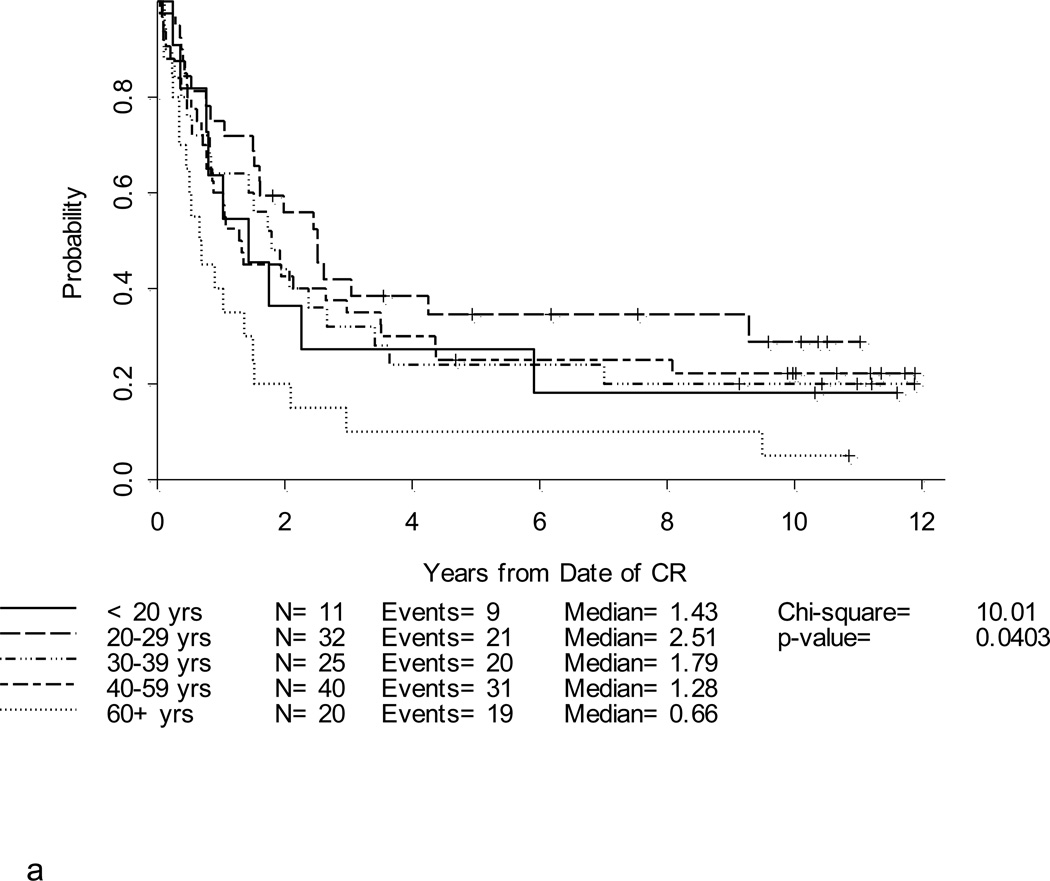

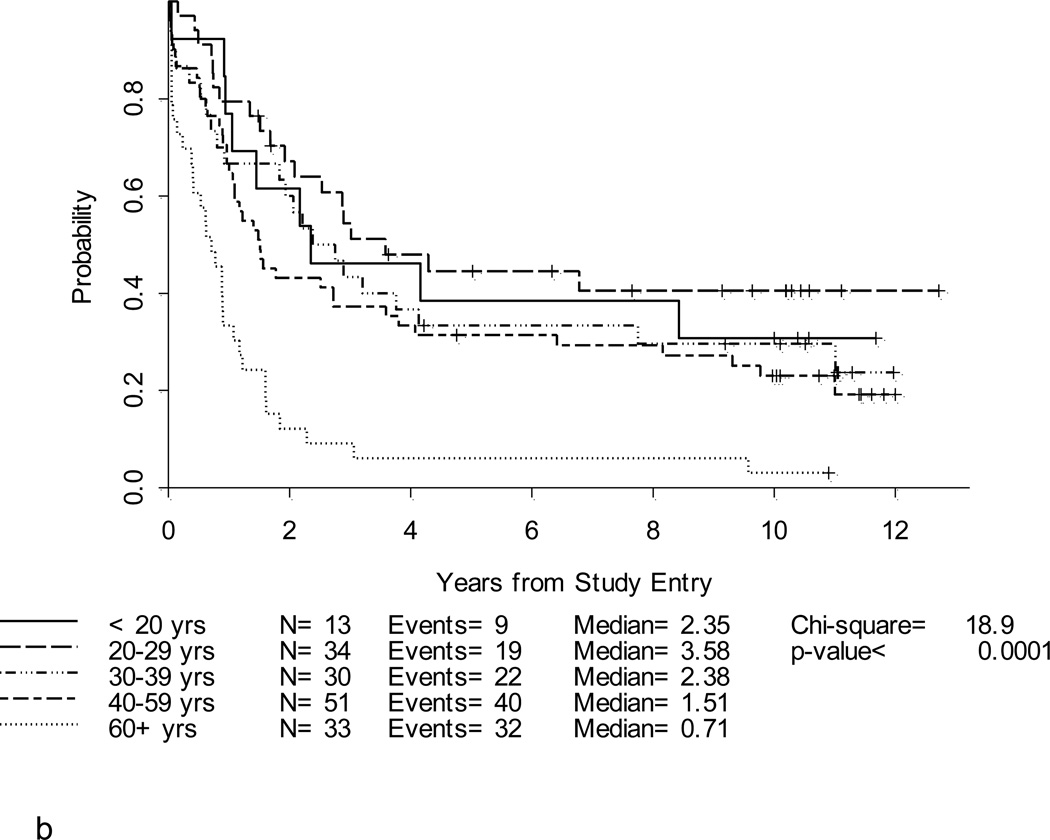

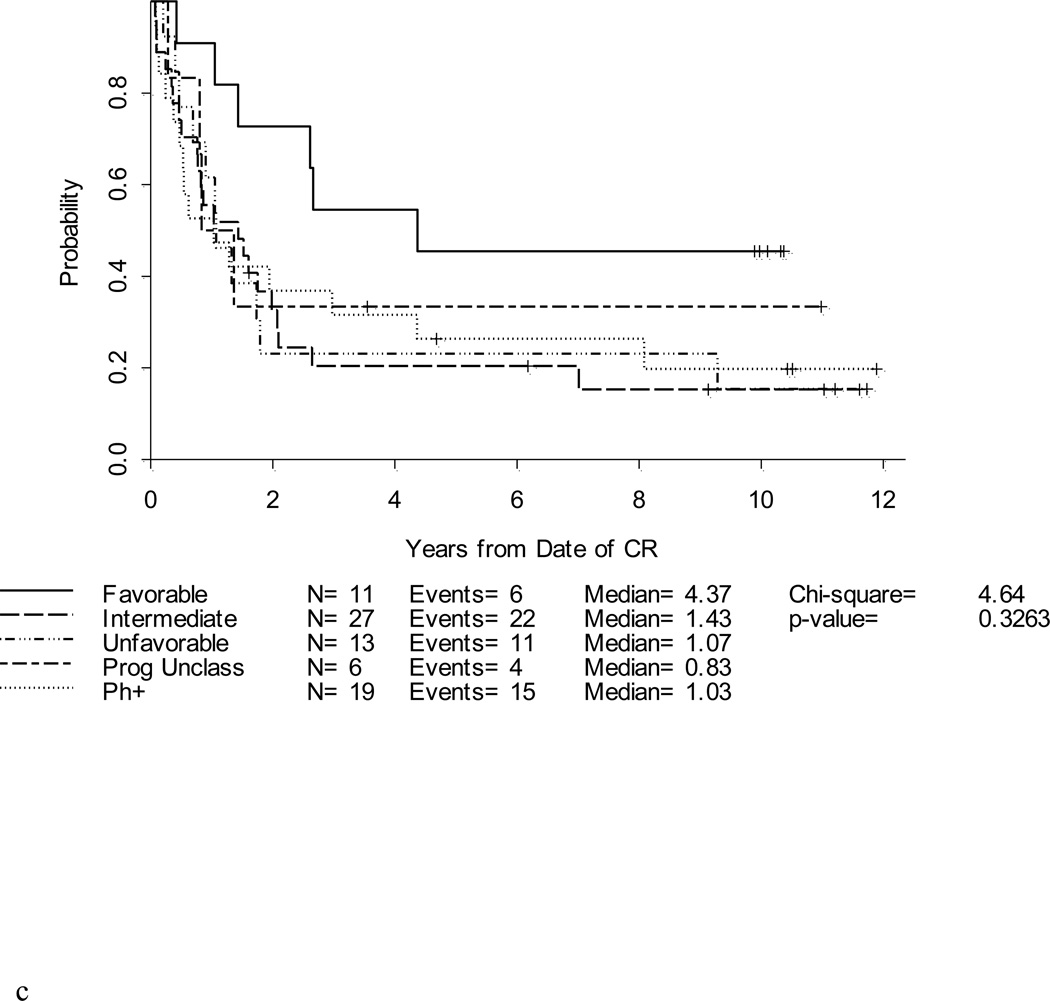

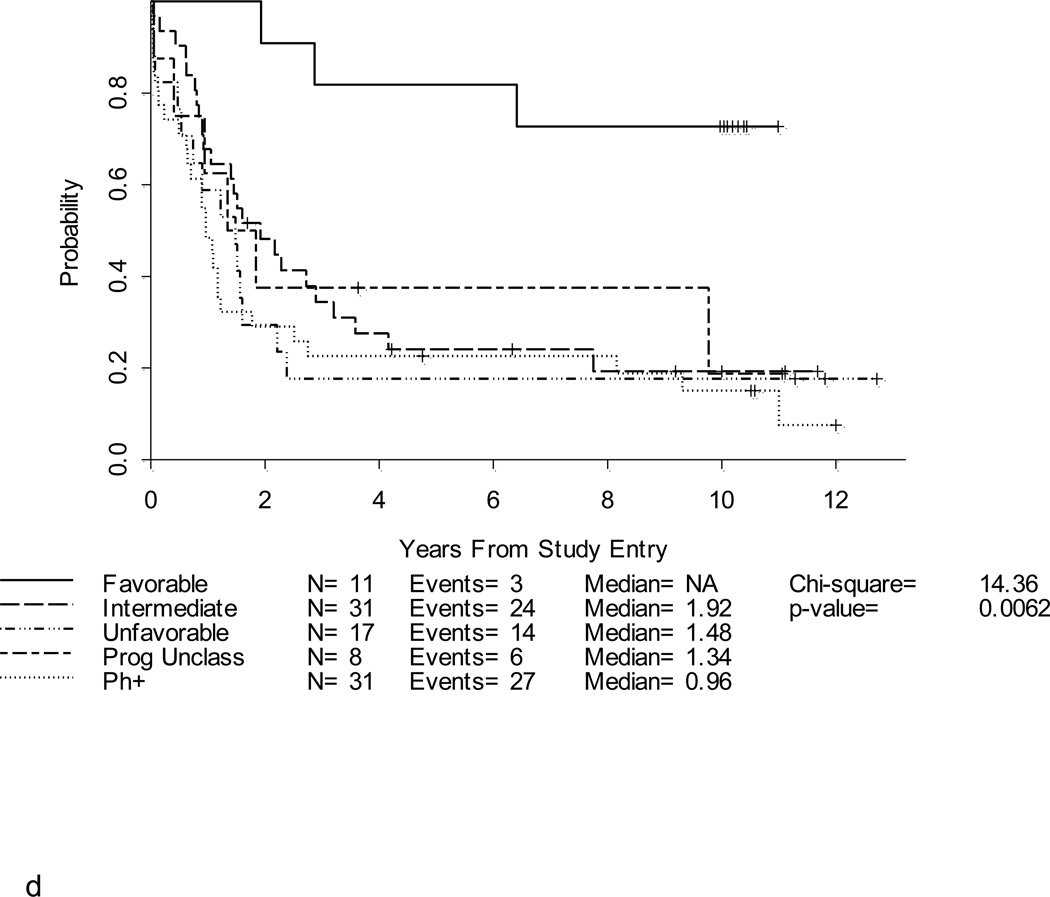

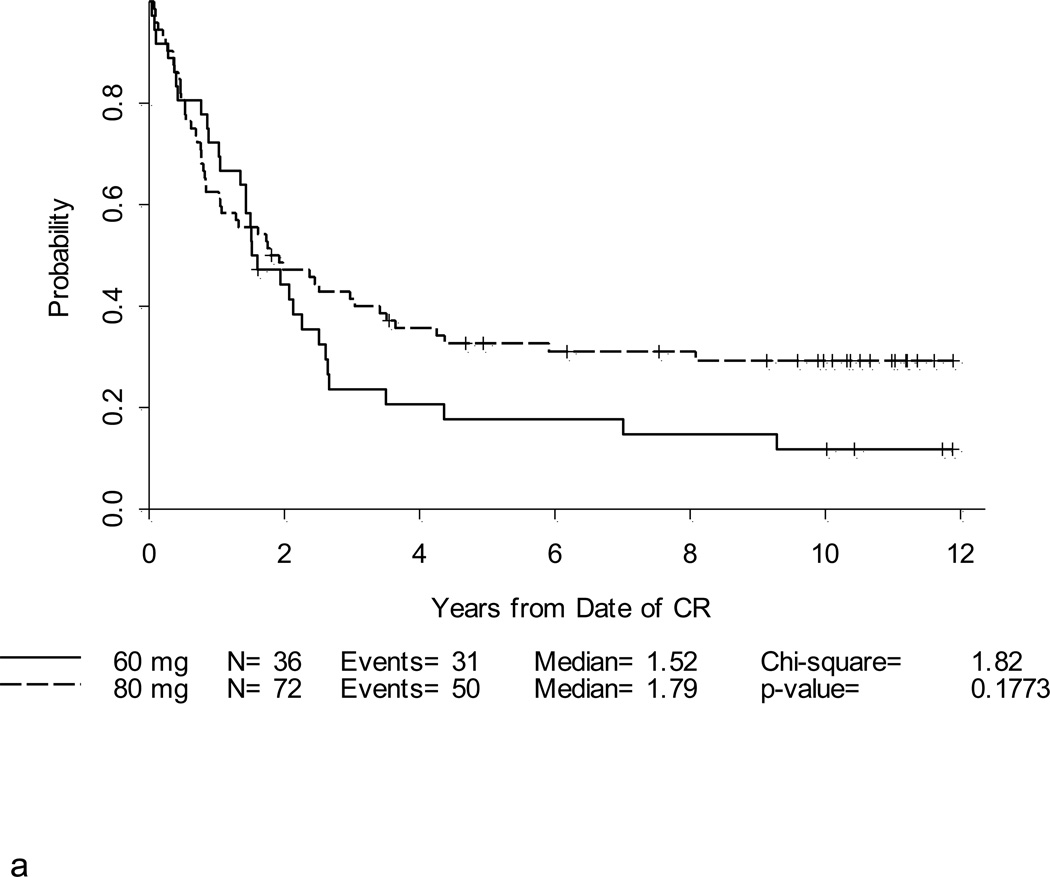

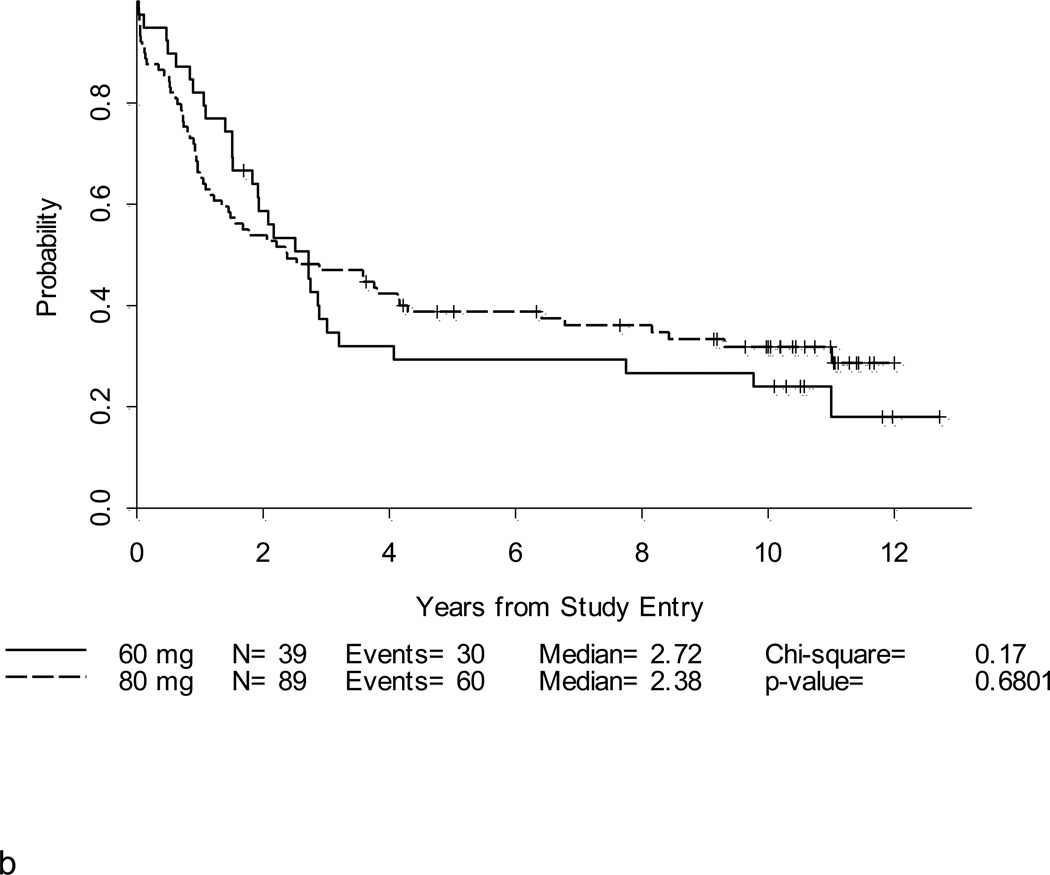

After a median follow-up of 10.4 years (range, 1.5 – 12.7 years) for 39 surviving patients, the 5-year DFS and overall survival (OS) for the entire study population were 25% (95% CI, 18–33%) and 30% (95% CI,23–37%), respectively (Table 2; Figures 2a and 2b). Notably, with longer follow-up, there were only 3 additional events (all marrow relapses) reported between years 3–5 of follow-up. After year 5, there were only 3 more events; only one of these was due to disease relapse. Thus, there were very few relapses after 3 years. Patients under 60 years fared significantly better than patients ≥ 60 years where 3-year DFS and OS were only 10% and 6%, respectively, p < 0.001 (Figures 3a and 3b). For younger adults receiving the 80 mg/m2 daunorubicin dose during induction and post-remission therapy, 5-year DFS and OS were 33% and 39%, respectively, in comparison with DFS of 18% and OS of 29% for the patients < 60 years old who received 60 mg/m2 of daunorubicin (Figures 4a and 4b).

Figure 2. a. and b. Disease-free survival and Overall Survival.

One hundred and twenty-eight patients (80%) of the 161 enrolled onto CALGB 19802 achieved CR. The 5-year DFS was estimated at 25% (95% CI, 18–33%) (Figure 2a). Overall survival at 5-years for all 161 patients was 30% (95% CI, 23–37%) (Figure 2b).

Figure 3. a. b, c and d. DFS and OS by age and cytogenetic risk group.

Disease-free survival (Figure 3a) and overall survival (Figure 3b) by age. Disease-free survival (Figure 3c) and overall survival (Figure 3d) by cytogenetic risk group.

Figure 4. a and b. DFS and OS by daunorubicin dose for patients < 60 years old.

Complete remission was achieved in 36 of 39 (92%) patients who received the 60 mg/m2 daily dose of daunorubicin. Five-year DFS for these patients was estimated at 18% (95% CI,7–32%) and OS was 29% (16–44%). For the 89 patients who received the 80 mg/m2 daily daunorubicin dose, CR was achieved in 72 (81%). The 5-year DFS for these patients was 33% (95% CI, 22–44%) and OS was 39% (29–49%).

Neither initial WBC count nor gender impacted DFS or OS in this study. However, survival differed according to both immunophenotype and cytogenetic subset. Patients with precursor B-cell ALL had a hazard ratio for DFS of 1.5 compared to patients with precursor T-cell ALL (p=0.21) and had a significantly worse OS than precursor T-cell patients with a hazard ratio of 1.9 (p= 0.035). Cytogenetics remained an important prognosticator (Figures 3c and 3d). For the 11 patients with a favorable karyotype, the DFS was 45% at 5 years and the OS was 82%.

CNS Prophylaxis

One goal of CALGB 19802 was to replace CNS irradiation by combining weekly high dose systemic intravenous and sequential oral methotrexate administration with IT methotrexate. Approximately one-third of evaluable patients achieved an average serum methotrexate level in the target range of 1–2 µM at 30 hours during these CNS-directed treatment modules. There was a trend towards lower CNS relapse rates when higher 30-hour methotrexate concentrations were achieved; however this not statistically significant

Overall, 14 (9%) patients experienced a CNS relapse; nine (6%) patients had an isolated CNS relapse, and five (3%) patients had simultaneous CNS and bone marrow relapses. Of note, isolated CNS relapses were more frequently reported in patients with favorable cytogenetics. Five of 11 (45%) patients with favorable cytogenetics relapsed in the CNS; these relapses occurred from 0.4–2.7 years after remission. Two of the CNS relapses in the favorable cytogenetics group occurred in patients with translocations involving T-cell receptor genes and the other three had precursor B-cell ALL with 12p deletions. In comparison, six of 31 (19%) with intermediate cytogenetics and only one (2%) of 47 patients with unfavorable karyotypes had an isolated CNS relapse (p = 0.0007).

Adherence to Protocol Therapy

Reasons for protocol discontinuation included: failure to achieve a remission in six patients (4%); death during treatment in 21 (12%); recurrent disease during treatment in 43 (27%); treatment related toxicity in 16 (10%); withdrawal of consent in 10 (6%); removal for alternative therapies (other than transplantation) in 2 patients; and for miscellaneous other reasons in 11 (7%)

Thirty-five patients (22%) completed all planned therapy on this multi-center study. Another 14 patients (9%) with adverse cytogenetics (either Ph+ or 11q23 translocation) underwent an allogeneic transplant in CR1, as recommended by the protocol. Four additional patients were removed from protocol therapy at their physician’s discretion and received hematopoietic cell transplantation in CR1; only one of these patients had centrally reviewed cytogenetics and had a complex karyotype.

DISCUSSION

The importance of anthracyclines for achievement of higher CR rates for adults with ALL was demonstrated in an early CALGB randomized clinical trial23; however, higher CR rates have not translated into significant prolongation in DFS or OS. In this study, where the median age was 40 years, older than all prior CALGB studies of adult ALL, we demonstrated that it was feasible to intensify daunorubicin and cytarabine during induction and post-remission therapy and give effective CNS prophylaxis without cranial irradiation. However, the CR rate of 80% for all patients and the overall DFS of 25% and OS of 30% were not better than what has previously been reported in three previous CALGB studies of adults with ALL. In partial explanation, the percentage of patients with adverse prognostic features on this study was higher than in any previous CALGB study -- the patients were older and 49% had an adverse karyotype.

Because the CR rate of adults with ALL is already high and requires only about 2 log reduction in the leukemia mass, we hypothesized that the benefit of dose escalation would be observed in a better DFS and OS, but probably not in a higher CR rate. This was true (Figure 4a) – the DFS curve for the 80 mg/m2 dose cohort crosses the 60 mg/m2 cohort DFS curve after two years and plateaued at a higher level with 10 year follow-up. Importantly, among patients who received 80 mg/m2 of daunorubicin there were only 4 relapses reported more than 3 years after achievement of CR.

The outcomes for patients <60 who received the highest cumulative dosing of daunorubicin were similar, but not better than the 41% 3-year DFS reported by Bassan et al in their study of non-Ph+ patients who received daunorubicin dose intensification during induction or post-remission therapy1 or the results of Todeschini et al13 where daunorubicin dose intensification during induction did not improve CR rates but resulted in improved DFS. In their study, Todeschini reported that patients who received a cumulative dose of at least 175 mg/m2 of daunorubicin during induction had a DFS of 44% in contrast to only 22% for those receiving less than 175 mg/m2. Among our patients ≥ 60 years old, we saw no benefit to dose intensification to a cumulative dose of daunorubicin 180 mg/m2 during induction; the treatment-related death rate was 21% and the DFS (10%) and OS (6%) remain very poor. A similar increase in toxicity among older adults and lack of overall survival benefit from liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine intensification was also noted in a recently published study from Thomas and colleagues at the MD Anderson Cancer Center. 24 Previously defined intermediate- and high-risk cytogenetic risk groups21,22,25,26 did not predict for different outcomes on this study. One interpretation of this observation is that the more dose intensive use of daunorubicin and cytarabine actually did provide a survival benefit to these patients with poor-risk ALL

We demonstrated that it is possible to replace cranial irradiation by administering intensive systemic methotrexate together with IT methotrexate prophylaxis. Isolated CNS relapses occurred in nine (6%) patients which is comparable to the CNS relapse rates reported on four prior CALGB studies that included cranial irradiation. CNS relapse rates on these four studies ranged from 9–14%. Our results are also similar to the 4% isolated CNS relapse rate that has been reported by the MD Anderson group in their long-term follow-up of their Hyper-CVAD regimen that does not employ cranial irradiation4. We attempted to adjust methotrexate dosing to maintain 1–2 µM concentrations 30 hours after initiation of high dose systemic methotrexate and IT methotrexate based on a report of its favorable effect on reducing CNS relapses20. Among 101 evaluable patients, there were no significant differences in CNS relapse rates noted as a function of mean 30-hour methotrexate levels. While we noted a trend toward fewer CNS relapses in patients with higher blood levels, 30-hour methotrexate levels higher than 2 µM were also associated with more systemic toxicities including mucositis and prolonged myelosuppression.

Further reductions in CNS relapse rates might be achieved by the earlier introduction of specific CNS-directed prophylaxis in future study regimens (rather than beginning 29 days after diagnosis as in CALGB 19802), or the substitution of dexamethasone for prednisone which has been associated with lower CNS and systemic relapse rates in pediatric and adult ALL regimens27,28, and/or the use of CNS irradiation only for patients at high risk of CNS relapse, such as T-cell ALL patients with high initial WBC counts29. A recent large retrospective analysis of CNS relapses in 467 adults with ALL reported no differences in relapse rates for those receiving CNS prophylaxis with cranial irradiation compared to those who did not receive CNS irradiation.17 It was noted that the only clinical factor associated with CNS relapse was a high initial lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level of > 1000 U/microliter30. In our study, we could not identify any associations between CNS relapse rate and immunophenotype or high initial WBC count; pre-treatment LDH was not routinely recorded.

One of the sobering observations was that 27% of patients relapsed prior to completion of protocol treatment. Another 22% of patients were not able to complete therapy due to toxicity – deaths during treatment (mostly during remission induction for younger adults receiving the 80 mg/m2 dose of daunorubicin and in older adults during both remission induction and during post-remission therapy) or removal from protocol therapy due to toxicity. Thus, early dose intensification of the myelosuppressive drugs, daunorubicin and cytarabine, was not a successful strategy to improve DFS or OS. It would be informative for other clinical investigators to report the percentage of all enrolled patients who complete all planned therapy on pediatric and adult ALL studies as well as the adherence to the timing of scheduled treatment for comparative purposes.

Recent retrospective studies examining outcomes of adolescents and younger adults with ALL have suggested that the non-myelosuppressive agents that are active in ALL, such as the glucocorticoids, vincristine, and l-asparaginase, are the critical drugs to intensify to improve DFS in higher risk children and older adolescents with ALL 31–33. While the intensification of these agents in regimens for older adults with ALL may pose a clinical challenge due to their own unique toxicities, early results from several pilot trials suggest that it is possible to employ this approach in adults up to the age of 30–40 years with encouraging, albeit, preliminary results34–36.

In conclusion, a singular dose intensive approach to the treatment of all adults with ALL is not likely to result in further significant survival benefits and there remains much room for improvement. The biological heterogeneity of adults with ALL suggests this may best be achieved by incorporation of biologically targeted agents into frontline therapy, as has been recently demonstrated with the addition of the tyrosine kinase inhibitors to frontline therapy for adults and children with Ph+ ALL, the promising early data from the pediatric groups on the addition of nelarabine to frontline therapy for children with T-cell leukemia/ lymphoma, and the addition of rituximab to frontline therapy which has been reported to improve relapse-free and overall survival in younger adults with CD20+ ALL compared to historical controls37. Thus, rather than further exploration of dose intensification as described here in CALGB 19802, innovative therapeutic strategies for adult ALL should be tailored to specific age groups and/or cytogenetic/molecular genetic subsets.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by National Cancer Institute grants CA31946, CA33601, CA41287, CA32291, CA 35279, CA03927, CA02599, CA101140, CA77658, the Coleman Leukemia Research Foundation, and the University of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassan R, Pogliani E, Casula P, et al. Risk-oriented postremission strategies in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: prospective confirmation of anthracycline activity in standard-risk class and role of hematopoietic stem cell transplants in high-risk groups. Hematol J. 2001;2(2):117–126. doi: 10.1038/sj/thj/6200091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gokbuget N, Hoelzer D, Arnold R, et al. Treatment of Adult ALL according to protocols of the German Multicenter Study Group for Adult ALL (GMALL) Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000 Dec;14(6):1307–1325. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70188-x. ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hofmann WK, Seipelt G, Langenhan S, et al. Prospective randomized trial to evaluate two delayed granulocyte colony stimulating factor administration schedules after high-dose cytarabine therapy in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2002 Oct;81(10):570–574. doi: 10.1007/s00277-002-0542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kantarjian H, Thomas D, O'Brien S, et al. Long-term follow-up results of hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone (Hyper-CVAD), a dose-intensive regimen, in adult acute lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer. 2004 Dec 15;101(12):2788–2801. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Larson RA. The U.S. trials in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Ann Hematol. 2004;83(Suppl 1):S127–S128. doi: 10.1007/s00277-004-0850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson RA, Dodge RK, Burns CP, et al. A five-drug remission induction regimen with intensive consolidation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: cancer and leukemia group B study 8811. Blood. 1995 Apr 15;85(8):2025–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le QH, Thomas X, Ecochard R, et al. Proportion of long-term event-free survivors and lifetime of adult patients not cured after a standard acute lymphoblastic leukemia therapeutic program: adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia-94 trial. Cancer. 2007 May 15;109(10):2058–2067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldstone AH, Richards SM, Lazarus HM, et al. In adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the greatest benefit is achieved from a matched sibling allogeneic transplantation in first complete remission, and an autologous transplantation is less effective than conventional consolidation/maintenance chemotherapy in all patients: final results of the International ALL Trial (MRC UKALL XII/ECOG E2993) Blood. 2008 Feb 15;111(4):1827–1833. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-116582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas X, Boiron JM, Huguet F, et al. Outcome of treatment in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: analysis of the LALA-94 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2004 Oct 15;22(20):4075–4086. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bassan R, Pogliani E, Lerede T, et al. Fractionated cyclophosphamide added to the IVAP regimen (idarubicin-vincristine-L-asparaginase-prednisone) could lower the risk of primary refractory disease in T-lineage but not B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia: first results from a phase II clinical study. Haematologica. 1999 Dec;84(12):1088–1093. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bassan R, Rohatiner AZ, Lerede T, et al. Role of early anthracycline dose-intensity according to expression of Philadelphia chromosome/BCR-ABL rearrangements in B-precursor adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematol J. 2000;1(4):226–234. doi: 10.1038/sj.thj.6200032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Linker C, Damon L, Ries C, Navarro W. Intensified and shortened cyclical chemotherapy for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2002 May 15;20(10):2464–2471. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Todeschini G, Tecchio C, Meneghini V, et al. Estimated 6-year event-free survival of 55% in 60 consecutive adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients treated with an intensive phase II protocol based on high induction dose of daunorubicin. Leukemia. 1998 Feb;12(2):144–149. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2400912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortes J, O'Brien SM, Pierce S, Keating MJ, Freireich EJ, Kantarjian HM. The value of high-dose systemic chemotherapy and intrathecal therapy for central nervous system prophylaxis in different risk groups of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 1995 Sep 15;86(6):2091–2097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamps WA, Bokkerink JP, Hakvoort-Cammel FG, et al. BFM-oriented treatment for children with acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation and treatment reduction for standard risk patients: results of DCLSG protocol ALL-8 (1991–1996) Leukemia. 2002 Jun;16(6):1099–1111. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pui CH, Campana D, Pei D, et al. Treating childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia without cranial irradiation. N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 25;360(26):2730–2741. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0900386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schrappe M, Reiter A, Ludwig WD, et al. Improved outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia despite reduced use of anthracyclines and cranial radiotherapy: results of trial ALL-BFM 90. German-Austrian-Swiss ALL-BFM Study Group. Blood. 2000 Jun 1;95(11):3310–3322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abromowitch M, Ochs J, Pui CH, Fairclough D, Murphy SB, Rivera GK. Efficacy of high-dose methotrexate in childhood acute lymphocytic leukemia: analysis by contemporary risk classifications. Blood. 1988 Apr;71(4):866–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamen BA. L'asparaginase and methotrexate combinations: clashes of empiric success and laboratory models? J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007 Sep;29(9):587–588. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181483e1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winick N, Shuster JJ, Bowman WP, et al. Intensive oral methotrexate protects against lymphoid marrow relapse in childhood B-precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1996 Oct;14(10):2803–2811. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.10.2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moorman AV, Harrison CJ, Buck GA, et al. Karyotype is an independent prognostic factor in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): analysis of cytogenetic data from patients treated on the Medical Research Council (MRC) UKALLXII/Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 2993 trial. Blood. 2007 Apr 15;109(8):3189–3197. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-051912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wetzler M, Dodge RK, Mrozek K, et al. Prospective karyotype analysis in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the cancer and leukemia Group B experience. Blood. 1999 Jun 1;93(11):3983–3993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottlieb AJ, Weinberg V, Ellison RR, et al. Efficacy of daunorubicin in the therapy of adult acute lymphocytic leukemia: a prospective randomized trial by cancer and leukemia group B. Blood. 1984 Jul;64(1):267–274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomas D, O'Brien S, Faderl S, et al. Anthracycline dose intensification in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: lack of benefit in the context of the fractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone regimen. Cancer. 2010 Oct 1;116(19):4580–4589. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cytogenetic abnormalities in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: correlations with hematologic findings outcome. A Collaborative Study of the Group Francais de Cytogenetique Hematologique. Blood. 1996 Apr 15;87(8):3135–3142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ribera JM, Ortega JJ, Oriol A, et al. Prognostic value of karyotypic analysis in children and adults with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia included in the PETHEMA ALL-93 trial. Haematologica. 2002 Feb;87(2):154–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conter V, Valsecchi MG, Silvestri D, et al. Pulses of vincristine and dexamethasone in addition to intensive chemotherapy for children with intermediate-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007 Jan 13;369(9556):123–131. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60073-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mitchell CD, Richards SM, Kinsey SE, Lilleyman J, Vora A, Eden TO. Benefit of dexamethasone compared with prednisolone for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: results of the UK Medical Research Council ALL97 randomized trial. Br J Haematol. 2005 Jun;129(6):734–745. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seibel NL, Steinherz PG, Sather HN, et al. Early postinduction intensification therapy improves survival for children and adolescents with high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Children's Oncology Group. Blood. 2008 Mar 1;111(5):2548–2555. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-070342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sancho JM, Ribera JM, Oriol A, et al. Central nervous system recurrence in adult patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia: frequency and prognosis in 467 patients without cranial irradiation for prophylaxis. Cancer. 2006 Jun 15;106(12):2540–2546. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boissel N, Auclerc MF, Lheritier V, et al. Should adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia be treated as old children or young adults? Comparison of the French FRALLE-93 and LALA-94 trials. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Mar 1;21(5):774–780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.02.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Bont JM, Holt B, Dekker AW, van der Does-van den Berg A, Sonneveld P, Pieters R. Significant difference in outcome for adolescents with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on pediatric vs adult protocols in the Netherlands. Leukemia. 2004 Dec;18(12):2032–2035. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stock W, La M, Sanford B, et al. What determines the outcomes for adolescents and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated on cooperative group protocols? A comparison of Children's Cancer Group and Cancer and Leukemia Group B studies. Blood. 2008 Sep 1;112(5):1646–1654. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-130237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DeAngelo DJ, Dahlberg S, Silverman LB, et al. A multicenter phase II study using a dose intensified pediatric regimen in adults with untreaetd acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2007:110. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huguet F, Leguay T, Raffoux E, et al. Pediatric-inspired therapy in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the GRAALL-2003 study. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Feb 20;27(6):911–918. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ribera JM, Oriol A, Sanz MA, et al. Comparison of the results of the treatment of adolescents and young adults with standard-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia with the Programa Espanol de Tratamiento en Hematologia pediatric-based protocol ALL-96. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Apr 10;26(11):1843–1849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thomas DA, O'Brien S, Faderl S, et al. Chemoimmunotherapy with a modified hyper-CVAD and rituximab regimen improves outcome in de novo Philadelphia chromosome-negative precursor B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Aug 20;28(24):3880–3889. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.9456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]