Abstract

Background and objectives

The relationship of kidney function and CKD risk factors to structural changes in the renal parenchyma of normal adults is unclear. This study assessed whether nephron hypertrophy and nephrosclerosis had similar or different associations with kidney function and risk factors.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

From 1999 to 2009, 1395 living kidney donors had a core needle biopsy of their donated kidney during transplant surgery. The mean nonsclerotic glomerular volume and glomerular density (globally sclerotic and nonsclerotic) were estimated using the Weibel and Gomez stereologic methods. All tubules were counted in 1 cm2 of cortex to determine a mean profile tubular area. Nephron hypertrophy was identified by larger glomerular volume, larger profile tubular area, and lower nonsclerotic glomerular density. Nephrosclerosis was identified by higher globally sclerotic glomerular density.

Results

The mean (±SD) age was 44±12 years, 24-hour urine albumin excretion was 5±7 mg, measured GFR was 103±17 ml/min per 1.73 m2, uric acid was 5.2±1.4 mg/dl, and body mass index was 28±5 kg/m2. Of the study participants, 43% were men, 11% had hypertension, and 52% had a family history of ESRD. Larger glomerular volume, larger profile tubular area, and lower nonsclerotic glomerular density were correlated. Male sex, higher 24-hour urine albumin excretion, family history of ESRD, and higher body mass index were independently associated with each of these measures of nephron hypertrophy. Higher uric acid, higher GFR, and older age were also independently associated with some of these measures of nephron hypertrophy. Hypertension was not independently associated with measures of nephron hypertrophy. However, hypertension and older age were independently associated with higher globally sclerotic glomerular density.

Conclusions

Nephron hypertrophy and nephrosclerosis are structural characteristics in normal adults that relate differently to clinical characteristics and may reflect kidney function and risk factors via separate but inter-related pathways.

Keywords: glomerulosclerosis, nephropathy, renal biopsy, glomerulus, glomerular, hyperfiltration

Introduction

There has been much research on optimally characterizing kidney function and defining risk factors for CKD in order to predict outcomes such as kidney failure and mortality in the general population. However, how kidney function and risk factors relate to underlying structural changes in the renal parenchyma is less clear. Prior studies linked older age, CKD, and hypertension to lower nephron endowment (1–4). Both lower nephron endowment and metabolic abnormalities (e.g., diabetes) can lead to glomerulomegaly and tubular hypertrophy (5,6). Hypertrophy of glomeruli is associated with hypertrophy of the attached tubules with resultant kidney enlargement (7–10). In normal kidneys, the cortex consists only of nephrons and supporting vessels; increases in nephron size will disperse the glomeruli further apart, decreasing their density (11). Recent studies by Tsuboi et al. found that larger glomerular volume, lower profile tubular density, and lower profile glomerular density were correlated and predictive of kidney failure and other outcomes in a variety of early glomerulopathies (12–15). Conceptually, larger glomerular volume, lower profile tubular density (or larger mean profile tubular area), and lower glomerular density are all measures of larger nephron size (nephron hypertrophy).

Because of the bleeding risk, a renal biopsy is usually unavailable in settings in which there is not substantial kidney disease. Autopsy studies allow assessment of renal morphology in relation to CKD risk factors (16), but are typically of small sample size and are reflective of substantial disease burden at the time of death. Autopsy studies can be restricted to accidental deaths to be more reflective of the general population, but kidney function and CKD risk factors are not known at the time of an unexpected death. Living kidney donation provides a unique opportunity to relate kidney morphology to concurrent kidney function and CKD risk factors in a large sample of adults not selected on disease. Living donors undergo a standardized medical evaluation to assess kidney function and CKD risk factors just before donation and some transplant programs biopsy the kidney at the time of transplant surgery.

We hypothesized that morphologic measures of nephron hypertrophy (larger mean glomerular volume, larger mean profile tubular area, and lower glomerular density) would be correlated and reproducible in kidney donors. Furthermore, we hypothesized that kidney function and CKD risk factors among kidney donors would associate with nephron hypertrophy differently than with glomerulosclerosis.

Materials and Methods

Study Population

Our sample consisted of living kidney donors at the Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN) from 1999 to 2009 who had a protocol implantation biopsy. Each kidney donor underwent a standardized battery of tests as part of his or her predonation evaluation. In general, potential donors with a measured GFR below the fifth percentile for their age (17), 24-hour urine albumin>30 mg/24 h, fasting blood glucose>110 mg/dl, or any cardiovascular disease were excluded from donation. Hypertension was not an absolute contra-indication in older donors if BP was controlled with minimal antihypertensive therapy (monotherapy or two drugs if one was a thiazide). Obesity was not an absolute contra-indication to donation. Dyslipidemia and hyperuricemia were not typically exclusion criteria for donation. All donors were invited for a follow-up visit during the year after donation.

Donor Clinical Characteristics

The analyzed donor clinical characteristics were all part of the predonation evaluation. If multiple test results were present, the result temporally closest to kidney donation was used in the analysis. The kidney function tests were measured GFR by iothalamate clearance (17), 24-hour urine protein, and 24-hour urine albumin. An ambulatory BP monitor obtained systolic and diastolic BP readings every 10–20 minutes during an 18-hour period. The mean overall BP, mean active BP (4 p.m. to 9 p.m.), and mean nocturnal BP (12 a.m. to 5 a.m.) were obtained (18). Hypertension was defined by treatment with any antihypertensive therapy, systolic BP>140 mmHg, or diastolic BP>90 mmHg. Family history of ESRD was defined by the recipient being a blood relative of the donor. Metabolic characteristics obtained from a fasting morning blood draw included levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, glucose, and uric acid. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Metabolic syndrome was defined by a BMI>30 kg/m2 (waist circumference was unavailable) and any two of the following: (1) triglycerides>150 mg/dl (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0113), (2) HDL cholesterol<40 mg/dl in men and <50 mg/dl in women (to convert to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.0259), (3) fasting glucose>100 mg/dl, and (4) 18-hour mean systolic BP>130 mmHg, 18-hour mean diastolic BP>85 mmHg, or antihypertensive therapy (19). Measured GFR and 24-hour urine albumin were repeated at the follow-up visit.

Kidney Biopsy Morphology

An 18-gauge needle core biopsy of the cortex was taken with a biopsy gun (1.7-cm specimen slot) at the time of implantation (intraoperative) after revascularization of the kidney in the recipient. The tissue specimen was fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections 3 µm in depth were taken from the core and stained. This study used two consecutive central sections, one stained with periodic acid–Schiff and one stained with Masson trichrome, that were scanned into high-resolution digital images (Aperio XT system scanner, http://www.aperio.com). The periodic acid–Schiff-stained sections were magnified onto a tablet to manually outline the cortex, medulla, each complete or partial nonsclerotic glomerular tuft, and each globally sclerotic glomerulus (Supplemental Figure 1A). The cortex and each globally sclerotic glomerulus were also outlined on the trichrome-stained section. The presence of a capsule or corticomedullary junction was identified. To determine the mean profile tubular area, five consecutive 0.2-mm2 area circles were placed along the sectioned cortex starting from an end that had a capsule or opposite an end that had a corticomedullary junction to avoid medulla. All nontubular regions within these circles were excluded and the number of complete and partial tubules was counted (Supplemental Figure 1B). From these measures, we calculated the mean volume of nonsclerotic glomeruli (NSG; in millimeters cubed), NSG density (per millimeter cubed), globally sclerotic glomeruli (GSG) density (per millimeter cubed), total glomerular density (per millimeter cubed), and mean profile tubular area (in micrometers squared) using stereologic models as described in the Supplemental Methods. Detection of any interstitial fibrosis was also determined from these sections. We assessed reproducibility of morphometric measures with a subset of donors with two separate biopsy cores (both at the time of implantation).

Statistical Analyses

Morphometric measures of nephron size (nonsclerotic glomerular volume, mean profile tubular area, and glomerular density) were compared with scatterplots and were log-transformed for regression analyses. Each morphometric measure of nephron size was regressed on each donor clinical characteristic. Multivariable regression models were limited to the characteristics of age, sex, urine albumin, measured GFR (in milliliters per minute per 1.73 m2), hypertension, family history of ESRD, uric acid, and BMI (these characteristics had at least a borderline statistically significant association in prior work) (11). Glomerular density was analyzed as total glomerular density and by each type (NSG density and GSG density). For a sensitivity analysis, these analyses were repeated limited to donors with at least 4 mm2 of cortex on biopsy and donors with 0% interstitial fibrosis on biopsy, and were adjusted for the presence of capsule, the presence of corticomedullary junction, and the area of cortex. The subset of donors with two separate biopsy cores was used to determine intraclass correlation (proportion of total variation due to true differences between individuals) for each morphometric measure (20). The association of these morphometric measures with the residual GFR (follow-up/predonation) and change in urine albumin (follow-up−predonation) was also assessed.

Results

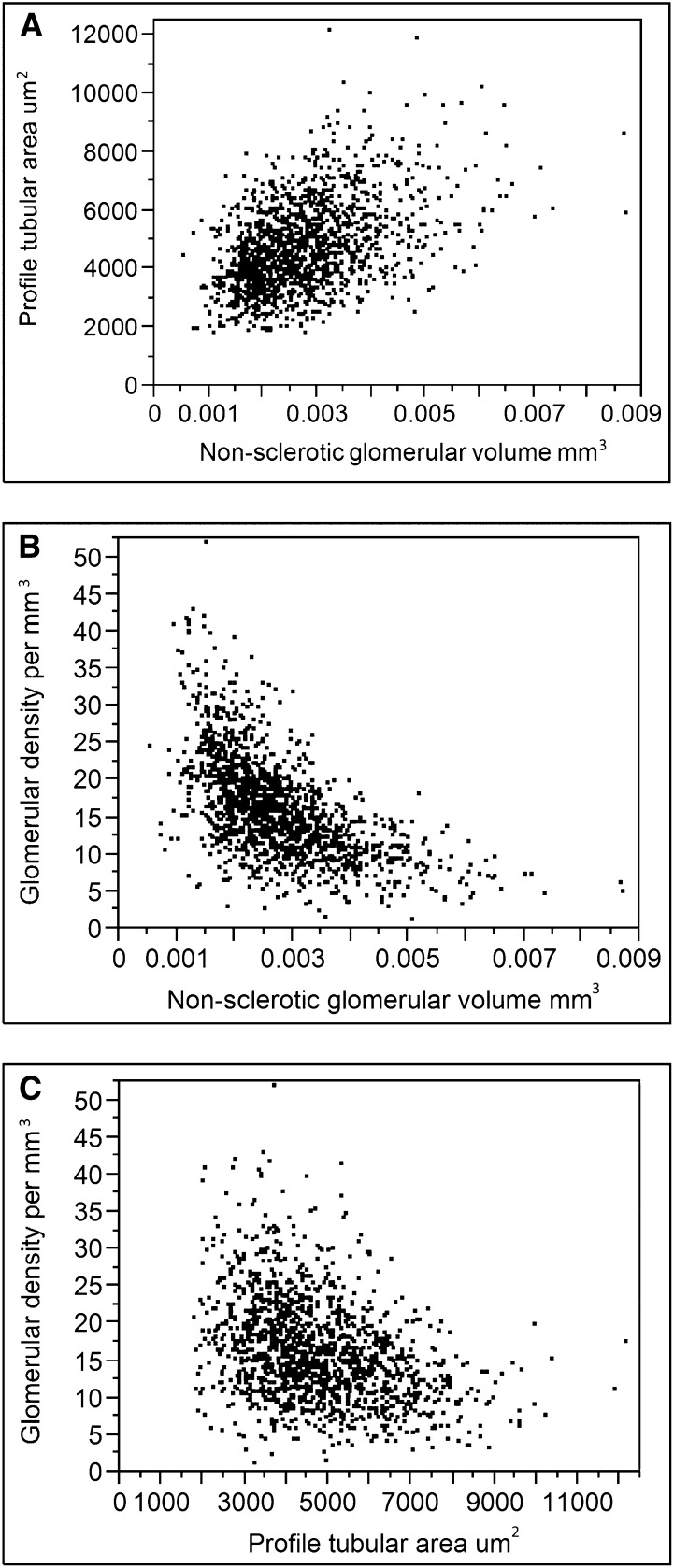

There were 1451 living kidney donors with an implantation biopsy of the renal cortex that was sectioned and scanned into an image file for analyses. Fifty donors were excluded for having <2 mm2 for area of cortex and six were excluded for severely distorted architecture (compressed appearance). Stained biopsy sections from the remaining 1395 donors (94% white) were analyzed and their characteristics are described in Table 1. The morphologic measures of nephron size were correlated. The mean glomerular volume was positively correlated with mean profile tubular area (rs=0.44, Figure 1A). Glomerular density was negatively correlated with mean glomerular volume (rs=−0.63, Figure 1B) and mean tubular area (rs=−0.37, Figure 1C).

Table 1.

Clinical and renal biopsy characteristics

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age, y | 44.0±12 |

| Men | 593 (42.5) |

| Kidney function | |

| 24-h Urine protein excretion, mg | 44.5±24.7 |

| 24-h Urine albumin excretion, mg | 5±7; 4 (0, 7) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.0±0.2 |

| Measured GFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 103±17 |

| Measured GFR, ml/min | 115±24 |

| 18-h Mean BP, mmHg | |

| Overall SBP | 119±9.1 |

| Active SBP | 122±7.4 |

| Nocturnal SBP | 107±9.7 |

| Overall DBP | 72±6.7 |

| Active DBP | 74±7.4 |

| Nocturnal DBP | 62±7.6 |

| Hypertension | 154 (11) |

| Other clinical characteristics | |

| Family history of ESRD | 717 (52) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl | 195±36 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dl | 118±67 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 56±16 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dl | 115±32 |

| Glucose, mg/dl | 95±8.6 |

| Uric acid, mg/dl | 5.2±1.4 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 28±5 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 170 (12.4) |

| Renal biopsy findings | |

| NSG, n | 16.8+8.2 |

| GSG, n | 0 (0, 1) |

| Profile area of cortex, mm2 | 6.7±2.4 |

| Profile NSG area, µm2 | 15,740±3966 |

| NSG volume, mm3 | 0.0028±0.0011 |

| Profile NSG density, per mm2 | 2.5±0.9 |

| NSG density, per mm3 | 15.3±6.6 |

| Profile GSG density, per mm2 | 0.0 (0.0, 0.1) |

| GSG density, per mm3 | 0.0 (0.0, 1.1) |

| Total glomerular density, per mm3 | 16.1±6.9 |

| Profile tubular area, µm2 | 4748±1513 |

| Capsule | 64 (4.6) |

| Corticomedullary junction | 209 (15) |

| Any interstitial fibrosis | 280 (23) |

| ≥5% interstitial fibrosis | 41 (2.9) |

Data are presented as the mean±SD, median (25 percentile, 75 percentile), or n (%). SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP; BMI, body mass index; NSG, nonsclerotic glomeruli; GSG, globally sclerotic glomeruli.

Figure 1.

Different measures of nephron size are correlated. Scatterplots comparing mean nonsclerotic glomerular volume to mean profile tubular area (A), mean nonsclerotic glomerular volume to glomerular density (B), and mean profile tubular area to glomerular density (C).

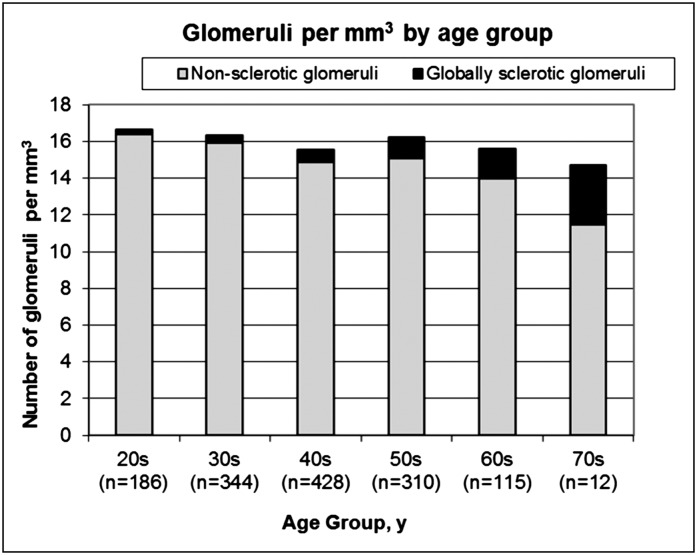

Tables 2 and 3 show the association between each morphometric measure and each clinical characteristic. Some donors were missing a 24-hour urine albumin value or a measured GFR, and the multivariable analysis was limited to the 1236 donors with these data. Larger glomerular volume was independently associated with male sex, higher urine albumin excretion, family history of ESRD, higher uric acid, and higher BMI. A larger mean profile tubular area was independently associated with older age, male sex, higher urine albumin excretion, higher GFR, family history of ESRD, and higher BMI. Both lower total glomerular density and lower nonsclerotic glomerular density were independently associated with older age, higher urine albumin excretion, family history of ESRD, higher uric acid, and higher BMI. Higher GSG density was independently associated with older age, hypertension, and lower urine albumin excretion. Figure 2 shows that the density of NSG was lower with age (−4.4% per decade, P<0.001), whereas density of GSG was higher with age (16% per decade, P<0.001) such that the total glomerular density became more gradually lower with age (−1.9% per decade, P=0.06).

Table 2.

Association of kidney function and CKD risk factors with glomerular volume and profile tubular area

| Characteristic | Mean Glomerular Volume | Mean Profile Tubular Area | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | |||||

| Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | |

| Age per 10 yr | −1.1 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.95 | 1.0 | 0.17 | 2.4 | 0.01 |

| Men | 15.8 | <0.001 | 7.3 | 0.004 | 6.9 | <0.001 | 4.9 | 0.03 |

| 24-h Urine protein excretiona | 1.6 | 0.13 | 0.005 | 0.99 | ||||

| Log 24-h urine albumin excretion, per doubling | 3.2 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.01 | 2.9 | <0.001 | 2.4 | <0.001 |

| Measured GFR (ml/min)a | 7.7 | <0.001 | 4.4 | <0.001 | ||||

| Measured GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m)2a | 1.5 | 0.15 | 2.0 | 0.09 | 1.9 | 0.03 | 3.1 | 0.002 |

| 18-h Overall SBPa | 5.5 | <0.001 | 2.3 | 0.01 | ||||

| 18-h Overall DBPa | 3.5 | <0.001 | 1.1 | 0.20 | ||||

| Hypertension | 8.5 | 0.01 | 3.6 | 0.29 | 7.9 | 0.01 | 3.4 | 0.27 |

| Family history of ESRD | 9.5 | <0.001 | 7.3 | 0.01 | 4.4 | 0.01 | 4.3 | 0.02 |

| Triglyceridesa | 4.1 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 0.03 | ||||

| HDL cholesterola | −5.4 | <0.001 | −3.0 | <0.001 | ||||

| LDL cholesterola | 1.6 | 0.12 | 0.8 | 0.36 | ||||

| Glucosea | 6.2 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 0.05 | ||||

| Uric acida | 9.0 | <0.001 | 3.6 | 0.01 | 2.9 | <0.001 | 0.15 | 0.90 |

| BMIa | 10.7 | <0.001 | 8.2 | <0.001 | 4.9 | <0.001 | 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 17.8 | <0.001 | 7.0 | 0.01 | ||||

SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP.

Per SD.

Table 3.

Association of kidney function and CKD risk factors with glomerular density

| Characteristic | Glomerular Density | NSG Density | GSG Density | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | Unadjusted | Multivariable Adjusted | |||||||

| Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | |

| Age, per 10 yr | −1.9 | 0.06 | −4.2 | <0.001 | −4.4 | <0.001 | −6.6 | <0.001 | 16 | <0.001 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Men | −10 | <0.001 | −3.2 | 0.29 | −10 | <0.001 | −3.2 | 0.31 | −6.8 | 0.02 | −3.8 | 0.31 |

| 24-h Urine protein excretiona | −0.8 | 0.54 | −1.2 | 0.37 | 1.97 | 0.22 | ||||||

| 24-h Urine albumin excretion, per doubling | −4.1 | <0.001 | −3.3 | <0.001 | −3.8 | <0.001 | −3.1 | <0.001 | −2.9 | 0.003 | −2.1 | 0.03 |

| Measured GFRa (ml/min) | −4.6 | <0.001 | −3.8 | 0.004 | −7.6 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Measured GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m)2a | 1.1 | 0.38 | −0.1 | 0.50 | 1.9 | 0.16 | −1.7 | 0.25 | −5.9 | <0.001 | 1.3 | 0.46 |

| 18-h Overall SBPa | −5.1 | <0.001 | −5.9 | <0.001 | 3.1 | 0.04 | ||||||

| 18-h Overall DBPa | −4.0 | <0.001 | −4.6 | <0.001 | 2.6 | 0.09 | ||||||

| Hypertension | −5.1 | 0.18 | 4.6 | 0.29 | −11.6 | 0.002 | −0.7 | 0.87 | 42 | <0.001 | 29 | <0.001 |

| Family history of ESRD | −9.6 | <0.001 | −10 | <0.001 | −9.2 | <0.001 | −11 | <0.001 | −5.5 | 0.07 | 3.1 | 0.33 |

| Triglyceridesa | −4.5 | <0.001 | −4.5 | <0.001 | −1.2 | 0.43 | ||||||

| HDL cholesterola | 6.0 | <0.001 | 5 | <0.001 | −6.7 | <0.001 | ||||||

| LDL cholesterola | −1.3 | 0.29 | 1.4 | 0.30 | 0.7 | 0.65 | ||||||

| Glucosea | −4.2 | <0.001 | −4.7 | <0.001 | 2.4 | 0.13 | ||||||

| Uric acida | −8.1 | <0.001 | −4.7 | 0.003 | −8.1 | <0.001 | −4.9 | 0.003 | 2.3 | 0.13 | −0.5 | 0.80 |

| BMIa | −10 | <0.001 | −8.0 | <0.001 | −9.8 | <0.001 | −7.4 | <0.001 | −2.8 | 0.06 | −2.8 | 0.09 |

| Metabolic syndrome | −15 | <0.001 | −15 | <0.001 | 2.1 | 0.66 | ||||||

SBP, systolic BP; DBP, diastolic BP.

Per SD.

Figure 2.

Density of nonsclerotic glomeruli and globally sclerotic glomeruli by age group.

The area of cortex contained in the biopsy section was correlated with larger glomerular volume, larger profile tubular area, and lower glomerular density; the presence of capsule associated with smaller glomeruli and a higher glomerular density; and the presence of corticomedullary junction associated lower glomerular density. However, clinical-morphologic associations were not substantively different after adjustment for these biopsy factors (Table 4). Findings were also similar when analyses were limited to donors with >4 mm2 cortex or to donors with no detectable interstitial fibrosis (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis of characteristics associated with glomerular volume, mean profile tubular area, total glomerular density, and globally sclerotic glomerular density

| Characteristic | Original Analysis (n=1236) | At least 4 mm2 of Cortex (n=1072) | 0% Interstitial Fibrosis (n=956)a | Adjusted Depth and Amount of Biopsy (n=1236) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | Percent Difference | P Value | |

| Mean nonsclerotic glomerular volume | ||||||||

| Age, per 10 yr | 0.06 | 0.95 | −0.1 | 0.96 | 0.3 | 0.76 | 0.3 | 0.75 |

| Men | 7.3 | 0.004 | 4.8 | 0.06 | 8.0 | 0.01 | 7.1 | 0.004 |

| 24-h Urine albumin excretion, per doubling | 1.8 | 0.01 | 1.8 | 0.01 | 1.5 | 0.05 | 1.3 | 0.04 |

| Measured GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m)2b | 2.0 | 0.08 | 1.1 | 0.35 | 1.7 | 0.18 | 2.2 | 0.05 |

| Hypertension | 3.6 | 0.29 | 2.1 | 0.55 | 10 | 0.02 | 3.7 | 0.27 |

| Family history of ESRDb | 7.3 | <0.001 | 7.7 | <0.001 | 6.6 | 0.01 | 7.0 | <0.001 |

| Uric acidb | 3.6 | 0.01 | 4.4 | 0.001 | 3.7 | 0.01 | 3.6 | 0.01 |

| BMIb | 8.2 | <0.001 | 8.3 | <0.001 | 8.0 | <0.001 | 8.4 | <0.001 |

| Area of cortex | 3.0 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Corticomedullary junction | 0.3 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Capsule | −13 | 0.01 | ||||||

| Mean profile tubular area | ||||||||

| Age, per 10 yr | 2.4 | 0.01 | 2.4 | 0.02 | 2.6 | 0.01 | 2.7 | 0.003 |

| Men | 4.9 | 0.03 | 3.7 | 0.11 | 6.8 | 0.01 | 4.5 | 0.04 |

| 24-h Urine albumin excretion, doubling | 2.4 | <0.001 | 2.2 | <0.001 | 2.0 | 0.003 | 1.8 | 0.001 |

| Measured GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m)2b | 3.1 | 0.002 | 3.0 | 0.01 | 3.2 | 0.004 | 3.3 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 3.4 | 0.27 | 3.4 | 0.31 | 4.1 | 0.28 | 3.7 | 0.21 |

| Family history of ESRDb | 4.3 | 0.02 | 5.2 | 0.01 | 4.3 | 0.04 | 4.0 | 0.03 |

| Uric acidb | 0.15 | 0.90 | 0.6 | 0.63 | −0.8 | 0.55 | 0.1 | 0.93 |

| BMIb | 4.2 | <0.001 | 4.3 | <0.001 | 3.9 | <0.001 | 4.5 | <0.001 |

| Area of cortex | 3.3 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Corticomedullary junction | 3.4 | 0.18 | ||||||

| Capsule | −5.3 | 0.19 | ||||||

| Total glomerular density | ||||||||

| Age, per 10 yr | −4.2 | <0.001 | −3.6 | 0.01 | −5.6 | <0.001 | −4.2 | <0.001 |

| Men | −3.2 | 0.29 | −0.9 | 0.77 | −3.8 | 0.27 | −3.5 | 0.24 |

| 24-h Urine albumin excretion, doubling | −3.3 | <0.001 | −3.5 | <0.001 | −2.2 | 0.02 | −2.9 | <0.001 |

| Measured GFR (ml/min per 1.73 m)2b | −0.1 | 0.50 | −1.1 | 0.44 | −1.2 | 0.43 | −1.0 | 0.46 |

| Hypertension | 4.6 | 0.29 | 2.5 | 0.57 | −3.6 | 0.49 | 4.4 | 0.31 |

| Family history of ESRDb | −10 | <0.001 | −10 | <0.001 | −11 | <0.001 | -9.0 | <0.001 |

| Uric acidb | −4.7 | 0.003 | −5.8 | <0.001 | −4.9 | 0.01 | −4.7 | 0.003 |

| BMIb | −8.0 | <0.001 | -7.2 | <0.001 | −7.7 | <0.001 | −8.3 | <0.001 |

| Area of cortex | −1.9 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Corticomedullary junction | −7.7 | 0.03 | ||||||

| Capsule | 26 | <0.001 | ||||||

| GSG density | ||||||||

| Age, per 10 yr | 13.5 | <0.001 | 14.4 | <0.001 | 8.4 | <0.001 | 13.6 | <0.001 |

| Men | −3.8 | 0.31 | −5.7 | 0.13 | −2.9 | 0.44 | −4.1 | 0.27 |

| 24-h Urine albumin excretion, doubling | −2.1 | 0.03 | −2.1 | 0.04 | −0.8 | 0.44 | −2 | 0.05 |

| Measured GFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2b | 1.3 | 0.03 | 0.6 | 0.74 | −1.1 | 0.52 | 1.3 | 0.45 |

| Hypertension | 28.8 | <0.001 | 26 | <0.001 | 16.4 | 0.01 | 28.5 | <0.001 |

| Family history of ESRDb | 3.1 | 0.33 | 3.5 | 0.29 | 5.2 | 0.10 | 3 | 0.35 |

| Uric acidb | −0.5 | 0.80 | 0.1 | 0.99 | −1.5 | 0.44 | −0.5 | 0.8 |

| BMIb | −2.8 | 0.09 | −2.4 | 0.17 | 0.4 | 0.82 | −3 | 0.07 |

| Area of cortex | −0.4 | 0.57 | ||||||

| Corticomedullary junction | −7.5 | 0.08 | ||||||

| Capsule | 10.9 | 0.17 | ||||||

All findings are multivariable adjusted.

Only 2.9% of donors had ≥5% interstitial fibrosis, but we used the strictest criteria for this sensitivity analysis.

Per SD.

We assessed the reproducibility of each of these morphometric measures of nephron size among 31 donors with two separate needle core biopsies of cortex. The mean area of cortex for this subset was 6.9 mm2, and was thus representative of the full sample (mean area of cortex was 6.7 mm2 for all 1395 donors). The intraclass correlation coefficients (proportion of variation not due to measurement error) ranked from highest to lowest for each morphometric measures was as follows: glomerular density (0.65), NSG density (0.61), mean glomerular volume (0.44), mean profile tubular area (0.31), and GSG density (0.12) (Supplemental Table 1).

There were 830 donors (59%) 830 donors (59%) who returned for a follow-up visit a mean of 6 months after donation. The mean (±SD) follow-up measured GFR was 74±17 ml/min and follow-up 24-hour urine albumin excretion was 6±15 mg (median 0 [25th percentile, 75th percentile, 0, 5] mg). The mean residual GFR (follow-up GFR/predonation GFR) was 65%. Only higher GSG density predicted a lower residual GFR at follow-up (Table 5) and this persisted with age-adjustment (-1.0% per SD, p=0.01). A measured GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 occurred in 33% of donors at follow-up. Only higher GSG Density per SD associated with a follow-up measured GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (OR=5.4, p=0.002), but not after age adjustment (OR=1.0, p=0.5). None of the morphometric measures predicted a change in 24-hour urine albumin excretion (Table 5).

Table 5.

Association of renal biopsy morphometric measures at time of donation with the change in kidney function at follow-up a mean 6 months after donation

| Renal Biopsy Morphometric Measures at Donationa | Residual GFRb | Change in 24-h Urine Albuminc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent Change | P Value | Change (mg) | P Value | |

| Mean glomerular volume | 0.5 | 0.23 | 0.9 | 0.08 |

| Mean profile tubular area | −0.1 | 0.86 | 0 | 0.20 |

| Glomerular density | −0.5 | 0.15 | −0.7 | 0.16 |

| NSG density | −0.2 | 0.50 | −0.5 | 0.25 |

| GSG density | −1.4 | <0.001 | −0.6 | 0.20 |

Percent changes are per characteristic.

Per SD.

Calculated as follows: Follow-Up GFR/Predonation GFR × 100%.

Calculated as follows: Follow-Up 24-Hour Urine Albumin − Predonation 24-Hour Urine Albumin.

Discussion

Despite selection on health, living kidney donors still vary considerably with respect to kidney function and CKD risk factors. Structural findings in the kidney could provide insight into the pathology of early CKD. We found that older age, male sex, albuminuria, higher GFR, family history of ESRD, hyperuricemia, and obesity associate with larger nephron size, as detected by three different morphometric measures. These morphometric measures (larger nonsclerotic glomerular volume, larger profile tubular area, and lower total and nonsclerotic glomerular density) are correlated and reflect true renal structural differences between individuals (intraclass correlation coefficients, 0.31–0.65). Characteristics that associate with larger nephron size are established risk factors for CKD or states that can precede CKD (e.g., hyperfiltration and mild albuminuria). Most of these characteristics were not associated with glomerulosclerosis, which instead had strong associations with hypertension and older age. The differing clinical associations with nephron hypertrophy compared with glomerulosclerosis suggest that there are two inter-related pathways of early CKD.

Our prior work in kidney donors found that a crude assessment of profile glomerular density had similar associations with kidney function and CKD risk factors (11). Profile glomerular density is simple and may be more practical for predicting outcomes in patients who have renal biopsies for early glomerulopathies (12–15). However, profile glomerular density is less accurate because at the same true glomerular density, smaller glomeruli are less likely to be sectioned and detected on a random profile than larger glomeruli. In this study, we obtained better measurements of profile glomerular density (per millimeter squared) and applied stereologic models to estimate true glomerular density (per millimeter cubed). Glomerular density was inversely correlated with mean glomerular volume and mean profile tubular area, confirming that the larger glomeruli and tubules disperse the glomeruli further apart and decrease their density. We also found important differences between the NSG density and GSG density. NSG density was lower with older age and had a similar association with kidney function and CKD risk factors to that seen with total glomerular density, glomerular volume, and profile tubular area. Conversely, GSG density was higher with age and had a strong association with hypertension not evident with NSG density. These microstructural findings parallel macrostructural findings in donor kidneys. Cortical hypertrophy (consistent with nephron hypertrophy) associates with higher GFR, albuminuria, and obesity, whereas cortical atrophy (consistent with higher GSG density) associates with older age (21).

The clinical characteristics that associate with nephron hypertrophy may represent two distinct pathophysiologic pathways: lower nephron endowment at the time of birth and metabolic risk factors later in life. There is substantial variation in nephron endowment across the population (22). A low nephron endowment is associated with larger glomeruli, low birth weight (23,24), and increased risk of kidney failure (25,26). Prior studies suggest a high rate of CKD linked to low nephron endowment and glomerulomegaly, particularly in certain racial or ethnic groups (27–30). The association of a family history of ESRD with morphometric measures of nephron hypertrophy in this study may represent a familial pattern of low nephron endowment, but we could not confirm this. Metabolic risk factors such as obesity and hyperuricemia have been linked to CKD (31–35). Obesity has been associated with both glomerulomegaly (36,37) and lower profile glomerular density (38). Artificially increasing uric acid levels in animal models results in glomerular hypertrophy (39). Hypertrophy of functional glomeruli with aging both helps compensate for age-related glomerulosclerosis and may itself cause glomerulosclerosis (40).

Donating a kidney results in hypertrophy of the nephrons in the remaining kidney (41,42). Because of this compensatory hypertrophy, the follow-up GFR is usually >50% the predonation GFR (mean of 65% in our study) (41,42). Our study found that the compensatory increase in GFR is less influenced by the baseline size of the nephrons and more influenced by the amount of nephrosclerosis (glomerulosclerosis) present. This is consistent with prior work by Poggio et al. who found that nephrosclerosis on implantation biopsy predicted less estimated GFR compensation post-donation (50).

Few studies have investigated the mean profile tubular area. A study in patients with minimal change disease found profile tubular density (number of tubules per area of cortex) to be correlated with glomerular density and inversely correlated with glomerular volume (14). We showed the same finding in kidney donors using the inverse measure, mean profile tubular area (area of cortex per tubule). The profile area of a sectioned tubule will be affected by the region (e.g., proximal versus distal) and the orientation of the tubule. By sampling a large number of sectioned tubules (mean 194 tubule profiles per donor) and excluding nontubular structures, the mean profile tubular area becomes more representative of biologic variation between people than these random factors. Nonetheless, our mean profile tubular area still had a relatively low intraclass correlation coefficient and sampling more tubule profiles may be needed to improve precision.

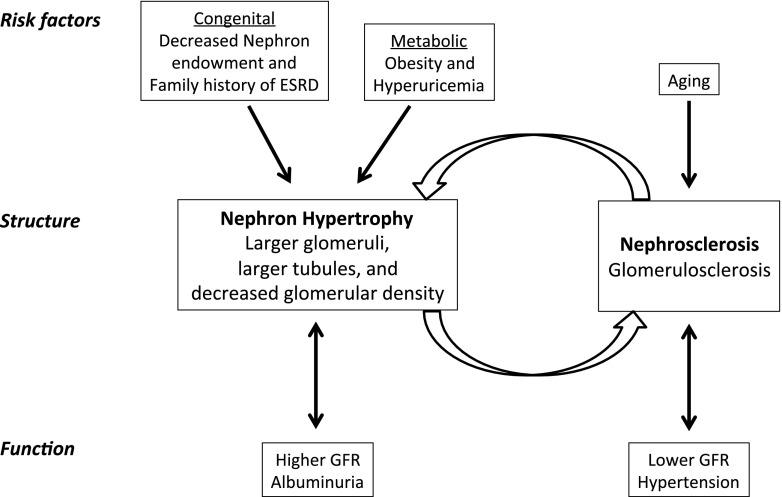

Higher GSG density was independently associated with older age and hypertension despite having poor measurement precision (low intraclass correlation coefficient). Glomerulosclerosis with aging and hypertension has been well described in a variety of populations (43–45). Interestingly, we also found that lower GSG density was associated with higher urine albumin excretion. This can be explained by dispersion of GSG farther apart by the enlarged nephrons that associate with albuminuria. Some clinical characteristics associated with higher GSG density (hypertension) differed from the clinical characteristics associated with larger nephron size (higher albuminuria, higher BMI, and family history of ESRD), which may be explained by two inter-related pathophysiologic pathways. Glomerulosclerosis (and nephrosclerosis) may be primarily driven by ischemia from arteriosclerosis with aging and hypertension. Glomerulomegaly (and nephromegaly) may be primarily driven by low nephron endowment at birth and by metabolic stress (obesity and hyperuricemia; Figure 3) (41,42).

Figure 3.

A conceptual model relating CKD risk factors and kidney function to the structural findings of nephron hypertrophy and nephrosclerosis (glomerulosclerosis) on renal biopsy among relatively healthy adults.

Our study has potential limitations. This study was conducted on donors who are selected on health. How these associations may differ in the general population with a wider range of pathology is unclear. Another limitation was that only 59% of donors returned for a follow-up visit because many chose to receive follow-up care closer to the area where they lived. This study investigated methodologic concerns with the stereologic analysis of clinical renal biopsies. As reported by others, we found glomerular density to be higher near the capsule (46). This can be explained by the deeper glomeruli being dispersed by the tubules of superficial glomeruli as well as glomerulosclerosis and tubular atrophy occurring initially in the subcapsular region. The nonsclerotic glomerular volume was smaller for glomeruli near the capsule. This is consistent with smaller ischemic glomeruli (thickened Bowman’s capsule and capillary wrinkling but not globally sclerotic) in the subcapsular region and compensatory enlargement of glomeruli near the corticomedullary junction (47). Another methodologic concern is variable tissue shrinkage with formalin dehydration and paraffin-embedding distorting morphometric measures (48). We found that the morphometric measures of larger nephron size were correlated with the cortical area on the sectioned biopsy specimen. Tissue shrinkage has a similar effect on both the morphometric measures of nephron size and the area of cortex biopsied (because the biopsy gun targets the same specimen size). However, the depth of the biopsy and the amount of tissue shrinkage (related to various factors with fixation, embedding, sectioning, mounting, and staining) (49) are reasonably viewed as having little or no relationship to donor clinical characteristics. This was confirmed by the clinical-morphologic associations remaining robust after adjustment for these biopsy factors.

In conclusion, kidney function and CKD risk factors had similar associations with three separate morphologic measures of nephron hypertrophy but different associations with glomerulosclerosis. Hypertrophy of nephrons, due to both low nephron endowment and metabolic stress, may contribute to the risk of CKD along different biologic pathways than age- and hypertension-related nephrosclerosis.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01-DK090358).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

H.E.E's current affiliation is Department of Internal Medicine, University of Missouri-Kansas City, Kansas City, Missouri.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.02560314/-/DCSupplemental.

See related editorial, “Nephron Hypertrophy and Glomerulosclerosis in Normal Donor Kidneys,” on pages 1832–1834.

References

- 1.Brenner BM, Garcia DL, Anderson S: Glomeruli and blood pressure. Less of one, more the other? Am J Hypertens 1: 335–347, 1988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller G, Zimmer G, Mall G, Ritz E, Amann K: Nephron number in patients with primary hypertension. N Engl J Med 348: 101–108, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyengaard JR, Bendtsen TF: Glomerular number and size in relation to age, kidney weight, and body surface in normal man. Anat Rec 232: 194–201, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puelles VG, Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Diouf B, Douglas-Denton RN, Bertram JF: Glomerular number and size variability and risk for kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 20: 7–15, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Singh GR, Douglas-Denton R, Bertram JF: Reduced nephron number and glomerulomegaly in Australian Aborigines: A group at high risk for renal disease and hypertension. Kidney Int 70: 104–110, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas MC, Burns WC, Cooper ME: Tubular changes in early diabetic nephropathy. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 12: 177–186, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hayslett JP, Kashgarian M, Epstein FH: Functional correlates of compensatory renal hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 47: 774–799, 1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson SC, Vallon V, Blantz RC: Kidney function in early diabetes: The tubular hypothesis of glomerular filtration. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F8–F15, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu B, Preisig PA: Compensatory renal hypertrophy is mediated by a cell cycle-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int 62: 1650–1658, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sigmon DH, Gonzalez-Feldman E, Cavasin MA, Potter DL, Beierwaltes WH: Role of nitric oxide in the renal hemodynamic response to unilateral nephrectomy. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1413–1420, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rule AD, Semret MH, Amer H, Cornell LD, Taler SJ, Lieske JC, Melton LJ, 3rd, Stegall MD, Textor SC, Kremers WK, Lerman LO: Association of kidney function and metabolic risk factors with density of glomeruli on renal biopsy samples from living donors. Mayo Clin Proc 86: 282–290, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuboi N, Kawamura T, Koike K, Okonogi H, Hirano K, Hamaguchi A, Miyazaki Y, Ogura M, Joh K, Utsunomiya Y, Hosoya T: Glomerular density in renal biopsy specimens predicts the long-term prognosis of IgA nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 39–44, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuboi N, Kawamura T, Miyazaki Y, Utsunomiya Y, Hosoya T: Low glomerular density is a risk factor for progression in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Nephrol Dial Transplant 26: 3555–3560, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koike K, Tsuboi N, Utsunomiya Y, Kawamura T, Hosoya T: Glomerular density-associated changes in clinicopathological features of minimal change nephrotic syndrome in adults. Am J Nephrol 34: 542–548, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuboi N, Koike K, Hirano K, Utsunomiya Y, Kawamura T, Hosoya T: Clinical features and long-term renal outcomes of Japanese patients with obesity-related glomerulopathy. Clin Exp Nephrol 17: 379–385, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Diouf B, Zimanyi M, Samuel T, McNamara BJ, Douglas-Denton RN, Holden L, Mott SA, Bertram JF: Distribution of volumes of individual glomeruli in kidneys at autopsy: Association with physical and clinical characteristics and with ethnic group. Am J Nephrol 33[Suppl 1]: 15–20, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rule AD, Gussak HM, Pond GR, Bergstralh EJ, Stegall MD, Cosio FG, Larson TS: Measured and estimated GFR in healthy potential kidney donors. Am J Kidney Dis 43: 112–119, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Textor SC, Taler SJ, Driscoll N, Larson TS, Gloor J, Griffin M, Cosio F, Schwab T, Prieto M, Nyberg S, Ishitani M, Stegall M: Blood pressure and renal function after kidney donation from hypertensive living donors. Transplantation 78: 276–282, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J: Metabolic syndrome–a new world-wide definition. A consensus statement from the International Diabetes Federation. Diabet Med 23: 469–480, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snecdecor GW, Cochran WG: Statistical Methods, 8th Ed., Ames, Iowa, Iowa State University Press, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang X, Vrtiska TJ, Avula RT, Walters LR, Chakkera HA, Kremers WK, Lerman LO, Rule AD: Age, kidney function, and risk factors associate differently with cortical and medullary volumes of the kidney. Kidney Int 85: 677–685, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoy WE, Douglas-Denton RN, Hughson MD, Cass A, Johnson K, Bertram JF: A stereological study of glomerular number and volume: Preliminary findings in a multiracial study of kidneys at autopsy. Kidney Int Suppl 83: S31–S37, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughson M, Farris AB, 3rd, Douglas-Denton R, Hoy WE, Bertram JF: Glomerular number and size in autopsy kidneys: The relationship to birth weight. Kidney Int 63: 2113–2122, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mañalich R, Reyes L, Herrera M, Melendi C, Fundora I: Relationship between weight at birth and the number and size of renal glomeruli in humans: A histomorphometric study. Kidney Int 58: 770–773, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luyckx VA, Brenner BM: Low birth weight, nephron number, and kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl 97: S68–S77, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luyckx VA, Brenner BM: The clinical importance of nephron mass. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 898–910, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoy WE, Samuel T, Mott SA, Kincaid-Smith PS, Fogo AB, Dowling JP, Hughson MD, Sinniah R, Pugsley DJ, Kirubakaran MG, Douglas-Denton RN, Bertram JF: Renal biopsy findings among Indigenous Australians: A nationwide review. Kidney Int 82: 1321–1331, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zimanyi MA, Hoy WE, Douglas-Denton RN, Hughson MD, Holden LM, Bertram JF: Nephron number and individual glomerular volumes in male Caucasian and African American subjects. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2428–2433, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughson MD, Puelles VG, Hoy WE, Douglas-Denton RN, Mott SA,Bertram JF: Hypertension, glomerular hypertrophy and nephrosclerosis: The effect of race. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 1399–1409, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McNamara BJ, Diouf B, Douglas-Denton RN, Hughson MD, Hoy WE, Bertram JF: A comparison of nephron number, glomerular volume and kidney weight in Senegalese Africans and African Americans. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 1514–1520, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu CY, McCulloch CE, Iribarren C, Darbinian J, Go AS: Body mass index and risk for end-stage renal disease. Ann Intern Med 144: 21–28, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iseki K, Ikemiya Y, Kinjo K, Inoue T, Iseki C, Takishita S: Body mass index and the risk of development of end-stage renal disease in a screened cohort. Kidney Int 65: 1870–1876, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feig DI: Uric acid: A novel mediator and marker of risk in chronic kidney disease? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 18: 526–530, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obermayr RP, Temml C, Gutjahr G, Knechtelsdorfer M, Oberbauer R, Klauser-Braun R: Elevated uric acid increases the risk for kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2407–2413, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF, Griffith JL, Salem DN, Levey AS: Uric acid and incident kidney disease in the community. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 1204–1211, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goumenos DS, Kawar B, El Nahas M, Conti S, Wagner B, Spyropoulos C, Vlachojannis JG, Benigni A, Kalfarentzos F: Early histological changes in the kidney of people with morbid obesity. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 3732–3738, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kambham N, Markowitz GS, Valeri AM, Lin J, D’Agati VD: Obesity-related glomerulopathy: An emerging epidemic. Kidney Int 59: 1498–1509, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsuboi N, Utsunomiya Y, Kanzaki G, Koike K, Ikegami M, Kawamura T, Hosoya T: Low glomerular density with glomerulomegaly in obesity-related glomerulopathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 735–741, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mazzali M, Kanellis J, Han L, Feng L, Xia YY, Chen Q, Kang DH, Gordon KL, Watanabe S, Nakagawa T, Lan HY, Johnson RJ: Hyperuricemia induces a primary renal arteriolopathy in rats by a blood pressure-independent mechanism. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 282: F991–F997, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wiggins JE, Goyal M, Sanden SK, Wharram BL, Shedden KA, Misek DE, Kuick RD, Wiggins RC: Podocyte hypertrophy, “adaptation,” and “decompensation” associated with glomerular enlargement and glomerulosclerosis in the aging rat: Prevention by calorie restriction. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 2953–2966, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen Z, Fang J, Li G, Zhang L, Xu L, Pan G, Ma J, Qi H: Compensatory changes in the retained kidney after nephrectomy in a living related donor. Transplant Proc 44: 2901–2905, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mueller TF, Luyckx VA: The natural history of residual renal function in transplant donors. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1462–1466, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kubo M, Kiyohara Y, Kato I, Tanizaki Y, Katafuchi R, Hirakata H, Okuda S, Tsuneyoshi M, Sueishi K, Fujishima M, Iida M: Risk factors for renal glomerular and vascular changes in an autopsy-based population survey: The Hisayama study. Kidney Int 63: 1508–1515, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaplan C, Pasternack B, Shah H, Gallo G: Age-related incidence of sclerotic glomeruli in human kidneys. Am J Pathol 80: 227–234, 1975 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rule AD, Amer H, Cornell LD, Taler SJ, Cosio FG, Kremers WK, Textor SC, Stegall MD: The association between age and nephrosclerosis on renal biopsy among healthy adults. Ann Intern Med 152: 561–567, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanzaki G, Tsuboi N, Utsunomiya Y, Ikegami M, Shimizu A, Hosoya T: Distribution of glomerular density in different cortical zones of the human kidney. Pathol Int 63: 169–175, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Newbold KM, Sandison A, Howie AJ: Comparison of size of juxtamedullary and outer cortical glomeruli in normal adult kidney. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol 420: 127–129, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West MJ: Tissue shrinkage and stereological studies. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2013: pii:pdb.top071860, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fox CH, Johnson FB, Whiting J, Roller PP: Formaldehyde fixation. J Histochem Cytochem 33: 845–853, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohashi Y, Thomas G, Nurko S, Stephany B, Fatica R, Chiesa A, Rule AD, Srinivas T, Schold JD, Navaneethan SD, Poggio ED: Association of metabolic syndrome with kidney function and histology in living kidney donors. Am J Transplant 13: 2342–2351, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.