Abstract

This study of patients under investigation for lung cancer (LC) aims to: 1) examine the prevalence of self-reported taste and smell alterations (TSAs) and their relationships with demographic and clinical characteristics; and 2) explore nutritional importance of TSAs by examining their associations with patient-reported weight loss, symptoms interfering with food intake, and changes in food intake.

Methods

Patients were recruited consecutively during investigation for LC from one university hospital in Sweden. Patient-reported information on TSAs, demographics, six-month weight history, symptoms interfering with food intake, and changes in food intake was obtained. Relationships between TSAs and other variables were examined using two-tailed significance tests. In addition, putative explanatory factors for weight loss were explored in those patients diagnosed with LC, since a relationship between TSAs and weight loss was found in this group.

Results

The final sample consisted of 215 patients, of which 117 were diagnosed with primary LC within four months of study inclusion and 98 did not receive a cancer diagnosis. The 38% prevalence of TSAs was identical in both groups, and were generally reported as mild and not interfering with food intake. However, a statistically significant relationship between TSAs and weight loss was found among patients with LC, with a median weight change of − 5.5% and a higher frequency of weight loss ≥ 10%. Patients with LC and weight loss ≥ 10%, had higher frequency of reporting TSAs, of decreased food intake and of ≥ 1 symptom interfering with food intake compared with those with less weight loss.

Conclusion

TSAs, although relatively mild, were present in 38% of patients with and without LC. Relationships between TSAs and weight loss were found among patients with LC, but not fully explained by decreased food intake. This highlights the complexity of cancer-related weight loss.

Involuntary weight loss in patients with cancer is a common problem, known to be a prognostic factor for treatment outcome and mortality [1,2] and with impact on quality of life [3]. At time of diagnosis, patients with lung cancer (LC) have been found to often have both a heavy symptom burden and be at risk for involuntary weight loss [1,4], with increasing rates of malnutrition during treatment [5,6]. Cancer-related weight loss is commonly caused by abnormal metabolism combined with reduced nutritional intake due to symptoms like nausea, loss of appetite or taste and smell alterations (TSAs) [7]. TSAs are well-recognized side effects of chemotherapy, with a recent review reporting 45–84% prevalence of taste alterations and 5–60% smell alterations related to chemotherapy [8]. Additionally, approximately 80% of patients with advanced cancer report TSAs [9]. These, along with other data [10,11], indicate that TSAs may play a role in the development of disease-related weight loss.

Research on TSAs in patients prior to treatment for cancer is scarce. Several older studies have investigated taste alterations in patients prior to treatment for various cancers, measuring taste sensitivity with clinical tests [12–14]. This methodology gives a fixed measure of patients’ taste sensitivity which can be compared to a control. Clinical assessment of smell sensitivity prior to cancer treatment has been used by Ovesen et al. [15] who found abnormal smell thresholds in patients with cancer. However, patients’ perceptions of TSAs are not captured by clinical assessment methods, but are better assessed by self-report questionnaires. While two studies report prevalence of self-reported TSAs of approximately 25% in patients prior to treatment for various types of cancer [16,17], to our knowledge no previous study has investigated relationships between self-reported TSAs, weight loss, and changes in food intake in patients prior to cancer treatment.

In this study, we use a symptom-specific self- report questionnaire to identify the presence of TSAs in a population of patients under investigation for LC, to: 1) examine the prevalence of TSAs and the relationships between TSAs, demographics, oral problems, smoking and clinical characteristics; and 2) explore the nutritional importance of TSAs by examining their associations with patient-reported weight loss, symptoms interfering with food intake, and changes in food intake.

Patients and methods

Data presented here derive from the longitudinal “Taste and Smell Project”, in which patients with suspected LC or diagnosed gastrointestinal cancer were recruited and first interviewed close to the time of diagnosis, i.e. prior to treatment, with approval from the regional ethical review board (for further information on the Taste and Smell Project see [18]). This article is based on data from the first baseline interview with patients with suspected LC.

Recruitment and study procedure

Patients were recruited consecutively from January 2011 to July 2012 from the pulmonary medicine department of a university hospital in Sweden. Eligible patients were ≥ 18 years, Swedish-speaking and under investigation for suspected LC. Exclusion criteria were cognitive impairments, previous head-neck cancer diagnosis, and not residing in Stockholm county. Eligible patients were asked by a clinic nurse if they were interested in receiving further information about the study. Those interested received telephone information from one of four research interviewers. Patients agreeing to participate gave written informed consent prior to interview. The structured face-to-face interviews were based on four questionnaires. The interviewer read each question to the patient and documented the verbal responses. Additional information was retrospectively obtained from medical records.

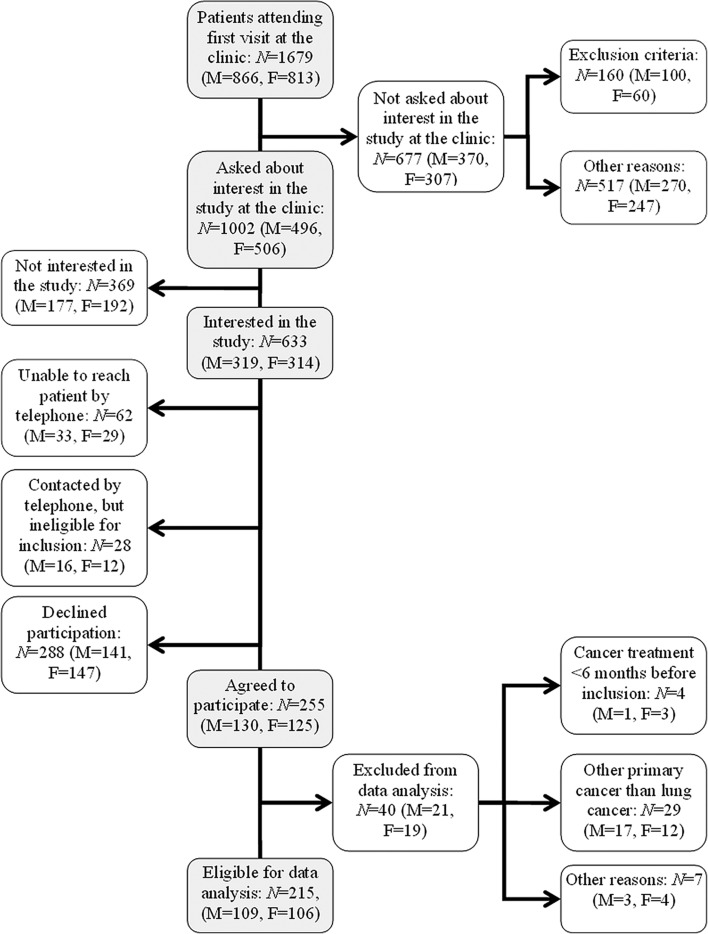

An overview of the recruitment and selection process is presented in Figure 1. A total of 255 patients under investigation for LC were interviewed for the Taste and Smell Project. Before analysis for the study presented here, data from 40 patients were excluded for the following reasons: other cancer diagnoses than primary LC (n = 29), having received anti- cancer treatment during the six months preceding the study (n = 4) or other reasons, e.g. major co-morbidity or cognitive impairments that became evident during interview (n = 7).

Figure 1.

Flow-chart of the recruiting and selection process.

Data collection instruments

Data on TSAs was collected by the Taste and Smell Survey (TSS), an instrument initially developed by Heald et al. [19] for use with HIV-infected patients. The TSS has also been used by a Canadian research group to investigate self-reported TSAs in patients with cancer [9,20] and has been translated into Swedish [18]. The TSS consists of 16 questions in which patients reported any alterations in taste or smell that had presented since initiation of the diagnostic process for lung disease. This results in a chemosensory complaint score ranging from 0 to 16 [19].

Nutritional information was acquired using the Swedish version of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) [21], an instrument for assessing nutritional status in patients with cancer in research and clinical settings [22]. The PG-SGA items used here are body weight at time of interview and six months earlier, level of food intake the previous month as compared to normal (unchanged, more than usual or less than usual) and a checklist of 13 symptoms that may have kept the patient from eating enough during the past two weeks. Two of these symptoms concern TSAs (“things taste funny or have no taste” and “smells bother me”).

Data on the presence and nature of oral problems, smoking status, and demographic data was obtained from additional study-specific questions.

Disease stage was determined by medical records and defined as stage I–II, stage IIIA, stage IIIB and stage IV. Early disease stage was defined as I–IIIA and advanced disease stage as IIIB–IV. The distinction between stage IIIA and IIIB was made based on the regional treatment guidelines as a patient with a stage IIIA tumor could be considered for surgery, whereas locally advanced tumors (stage IIIB) are generally considered non-resectable [23].

Data analysis

Patients were considered to report TSAs when indicating changes in taste or smell in one or more of the six questions in the TSS targeting altered perception of taste or smell in general, in relation to foods as well as the intensity of basic tastes (salt, sweet, sour, bitter) and smell. Percent weight change was calculated as the difference between weight six months earlier and at interview, using patients’ self-reports. Degree of weight loss was categorized into: 1) weight increased, stable or loss < 5%; 2) weight loss ≥ 5% to < 10%; or 3) weight loss ≥ 10%. These cut-offs were chosen based on previous research on malnutrition screening and assessment instruments [22,24]. Changes in food intake were dichotomized into having eaten “less than usual” versus having eaten “as usual or more”. Symptoms interfering with food intake were dichotomized into “no symptoms” and “≥ 1 symptom” on the PG-SGA. Smoking status was categorized into smokers, former smokers (quit > 1 year ago) and never smokers (includes occasional smoking), in line with categories in the Swedish National Lung Cancer Registry [25].

Patients were divided into four groups based on presence versus absence of TSAs and LC diagnosis. Tests for statistically significant differences between groups were performed between: 1) patients with LC reporting TSAs versus those with no TSAs; 2) patients without LC reporting TSAs versus those with no TSAs; and 3) patients reporting TSAs with LC versus those without LC. Since TSAs were found to associate with six-month weight loss among patients with LC, this relationship was further investigated only in patients with LC.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the frequencies of categorical variables and the distributions of continuous variables. Statistical group comparisons were performed using χ2-test or Fisher’s exact test for proportions and Mann-Whitney U-test, Kruskall-Wallis test or t-test for continuous or ordinal variables. All tests were two-tailed and a priori alpha was 0.05. Bonferroni-corrections were used when multiple (≥ 3) tests were performed on the same outcome.

Results

Demographics

As shown in Figure 1, data from 215 patients under investigation for LC was included for analysis. Of these, 117 patients (54%) received a primary LC diagnosis within four months after study inclusion. Ninety-eight patients (46%) had not been diagnosed with any cancer form at least six months after study inclusion.

Demographic data and clinical characteristics of included patients are shown in Table I. No statistically significant differences in age, gender, or education were found between patients with or without primary LC. Statistically significant differences were found for smoking status, as patients diagnosed with LC more frequently reported being smokers or former smokers than did patients without LC.

Table I.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of included patients.

| Primary lung cancer N (%) |

No cancer N (%) |

Total N (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Mean; SD | 68; 9 | 66; 10 | 67; 10 |

| Gender | |||

| Women | 63 (54) | 43 (44) | 106 (49) |

| Men | 54 (46) | 55 (56) | 109 (51) |

| Education | |||

| Elementary school | 23 (20) | 17 (18) | 40 (19) |

| High school | 60 (51) | 37 (38) | 97 (45) |

| University | 28 (24) | 38 (39) | 66 (31) |

| Other | 6 (5) | 5 (5) | 11 (5) |

| Missing data | – | 1 | 1 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoker | 49 (42)* | 26 (27) | 75 (35) |

| Former smoker | 58 (50)* | 42 (43) | 100 (47) |

| Never smoker | 10 (8) | 29 (30) | 39 (18) |

| Missing data | – | 1 | 1 |

| Tumor type | |||

| NSCLC1 | 94 (80) | – | – |

| SCLC | 8 (7) | – | – |

| Other2 | 15 (13) | – | – |

| Disease stage | |||

| I-IIIA | 58 (50) | – | – |

| IIIB-IV | 58 (50) | – | – |

| Missing data | 1 | – | – |

NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Includes adenocarcinoma, squamous cancer, adenosquamous cancer and other unspecified NSCLC.

Includes carcinoids, mesothelioma, multiple tumors of different kinds and unverified tumors.

P-value < 0.05.

Prevalence of TSAs (Aim 1)

Prevalence of TSAs was identical, 38%, in the patient groups with LC and without LC. No statistically significant differences were found among patients with or without TSAs regarding age or gender (data not shown). The TSS scores were generally low (median = 1 in full sample) and ranged from 0 to 12 and 0 to 14 among patients with LC and without cancer, respectively.

As shown in Table II, no statistically significant differences were found among the four patient groups based on diagnosis of LC and presence of TSAs with regard to age, gender or smoking status. In patients with LC, the distribution of disease stage and tumor type was similar between patients with and without TSAs. Oral problems were statistically significantly more frequently reported by patients without LC and TSAs (NLC-TSA group), compared to patients with LC reporting TSAs (LC-TSA group), and to patients without LC not reporting TSAs (NLC-NoTSA group). Among those reporting oral problems across all groups, the most common were dry mouth (59%), blisters (11%) and multiple problems (16%).

Table II.

Taste and smell alterations and lung cancer diagnosis in relation to demographical data, smoking status, oral problems and clinical characteristics.

| LC-TSA N = 44 |

LC-NoTSA N = 73 |

NLC-TSA N = 37 |

NLC-NoTSA N = 61 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean; SD | 70; 8 | 67; 10 | 67; 10 | 66; 11 |

| Gender, N (%) | ||||

| Women | 22 (50) | 41 (56) | 20 (54) | 23 (38) |

| Men | 22 (50) | 32 (44) | 17 (46) | 38 (62) |

| Smoking status, N (%) | ||||

| Smoker | 23 (52) | 26 (36) | 13 (35) | 13 (22) |

| Former smoker | 19 (43) | 39 (53) | 15 (41) | 27 (45) |

| Never smoker | 2 (5) | 8 (11) | 9 (24) | 20 (33) |

| Missing data | – | – | – | 1 |

| Oral problems, N (%) | ||||

| Yes | 11 (25) | 18 (25) | 20 (54)* | 14 (23) |

| None | 33 (75) | 55 (75) | 17 (46) | 47 (77) |

| Tumor type | ||||

| NSCLC | 35 (80) | 59 (81) | – | – |

| SCLC | 4 (9) | 4 (5) | – | – |

| Other | 5 (11) | 10 (14) | – | – |

| Disease stage | ||||

| I-IIIA | 21 (47) | 37 (51) | – | – |

| IIIB-IV | 23 (53) | 35 (49) | – | – |

| Missing data | – | 1 | – | – |

Bonferroni correction was performed.

LC-TSA: patients with primary lung cancer reporting TSAs; LC-NoTSA: patients with primary lung cancer not reporting TSAs; NLC-TSA: patients without cancer reporting TSAs; NLC-NoTSA: patients without cancer not reporting TSAs; NSCLC, non small-cell lung cancer; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer.

Statistically significant difference between NLC-TSA and LC-TSA and between NLC-TSA and NLC-NoTSA.

TSAs, weight loss, changes in food intake, and symptoms interfering with food intake (Aim 2)

Table III presents data on weight change, degree of weight loss, changes in food intake and symptoms interfering with food intake. Statistically significant relationships between TSAs and weight loss were seen among the LC-TSA group, with a lower median weight change (− 5.5%) and a higher frequency of reported weight loss ≥ 10% compared to both the LC-NoTSA group and the NLC-TSA group.

Table III.

Taste and smell alterations and lung cancer diagnosis in relation to weight change, weight loss, changes in food intake and presence of symptoms interfering with food intake.

| LC-TSA N = 44 | LC-NoTSA N = 73 | NLC-TSA N = 37 | NLC-NoTSA N = 61 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent six month weight change | ||||

| Median | − 5.5A | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| p25; p75 | − 10.8; 0 | − 3.0; 0 | − 4.7; 2.0 | − 2.0; 0.5 |

| Missing data (N) | 1 | 2 | – | 3 |

| Weight loss 1, N (%) | ||||

| Weight increased, stable or loss < 5% | 21 (49) | 59 (83) | 29 (78) | 51 (88) |

| Weight loss ≥ 5% to < 10% | 8 (18) | 5 (7) | 7 (19) | 5 (9) |

| Weight loss ≥ 10% | 14 (33)A | 7 (10) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Missing data | 1 | 2 | – | 3 |

| Food intake previous month | ||||

| As usual or more | 28 (64) | 61 (84) | 29 (78) | 53 (87) |

| Less than usual | 16 (36)B | 12 (16) | 8 (22) | 8 (13) |

| Symptoms interfering with food intake | ||||

| None | 26 (59) | 61 (84) | 26 (70) | 52 (85) |

| ≥ 1 symptom | 18 (41)B | 12 (16) | 11 (30) | 9 (15) |

Bonferroni correction was performed.

LC-TSA: Patients with primary lung cancer reporting TSAs; LC-NoTSA: Patients with primary lung cancer not reporting TSAs; NLC-TSA: Patients without cancer reporting TSAs; NLC-NoTSA: Patients without cancer not reporting TSAs.

Tests for statistically significant differences were performed between 1) weight loss ≥ 5% to < 10% versus weight increased, stable or loss < 5% and 2) weight loss ≥ 10% versus weight loss ≥ 5% to < 10% and weight increased, stable or loss < 5% combined.

Statistically significant difference between LC-TSA and LC-NoTSA and between LC-TSA and NLC-TSA.

Statistically significant difference between LC-TSA and LC-NoTSA.

Eating less than usual during the previous month and having ≥ 1 symptom interfering with food intake tended to be more frequently reported among all patients with TSAs, although these differences were statistically significant only among patients with LC. The PG-SGA item “things taste funny or have no taste” was marked as having caused insufficient food intake by eight patients, all with TSAs, and only one without a LC diagnosis. Two of these patients also indicated that food intake was hindered by “smells bother(ing) me” (data not shown). “Taste funny/no taste” was in each of these eight cases reported in conjunction with at least one other symptom on the same checklist, the most frequent being no appetite (n = 7), early satiety (n = 6) and nausea (n = 4).

The relationship between putative explanatory factors, including TSAs, and six-month weight loss among patients with LC was further explored in Table IV, where patients are grouped by degree of weight loss. Most LC patients (70%) reported “weight increased, stable or loss < 5%”, while 18% reported weight loss ≥ 10%. Statistically significant differences for proportions of patients in the three different weight loss categories were found: 1) between patients reporting less food intake and those eating as usual or more; 2) between those with ≥ 1 symptom and those without symptoms; 3) between patients with TSAs and those without TSAs.

Table IV.

Patients with lung cancer grouped into weight loss categories with putative explanatory variables in rows.

| Patients with lung cancer N = 114 (3 missing weight data) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight increased, stable or loss < 5% N = 80 (70%) | Weight loss ≥ 5% to < 10% N = 13 (12%) | Weight loss ≥ 10% N = 21 (18%) | |

| Age, N (%) | |||

| 39–67 | 39 (74) | 5 (9) | 9 (17) |

| 68–89 | 41 (67) | 8 (13) | 12 (20) |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Women | 41 (67) | 8 (13) | 12 (20) |

| Men | 39 (74) | 5 (9) | 9 (47) |

| Tumor type, N (%) | |||

| NSCLC | 63 (68) | 10 (11) | 19 (21) |

| SCLC | 6 (86) | – | 1 (14) |

| Other | 7 (70) | 3 (30) | – |

| Unverified | 4 (80) | – | 1 (20) |

| Disease stage, N (%) | |||

| I-IIIA | 44 (79) | 4 (7) | 8 (14) |

| IIIB-IV | 35 (61) | 9 (16) | 13 (23) |

| Missing data | 1 | – | – |

| Food intake previous month*, N (%) | |||

| As usual or more | 68 (78) | 10 (12) | 9 (10) |

| Less than usual | 12 (44.5) | 3 (11) | 12 (44.5) |

| Symptoms interfering with food intake*, N (%) | |||

| None | 66 (77) | 10 (11.5) | 10 (11.5) |

| ≥ 1 | 14 (50) | 3 (11) | 11 (39) |

| TSAs*, N (%) | |||

| Absent | 59 (83) | 5 (7) | 7 (10) |

| Present | 21 (49) | 8 (19.5) | 14 (32.5) |

NSCLC, non small-cell lung cancer; SCLC, small-cell lung cancer; TSAs, taste and smell alterations.

*P-value < 0.05.

Discussion

In this observational, cross-sectional study based on patient-reported outcomes, the 38% prevalence of self-reported TSAs did not differ between patients with LC prior to treatment and those not diagnosed with LC. The TSAs were generally mild as evidenced by low scores on the TSS. Patients with and without LC differed in that a statistically significant relationship between TSAs and self-reported weight loss was found among patients with LC, but not among patients without LC.

The prevalence of TSAs in our study was higher than that found by previous research using self-report data to identify TSAs in patients prior to cancer treatment [16,17]. One explanation for this may be our use of a symptom-specific questionnaire rather than a single global question, although the TSS has not previously been used in a population of patients under investigation for cancer. People with as mild TSAs as reported here might not designate this as a general “taste change” which a global question would imply, which indicates the TSS is a sensitive instrument for detecting TSAs; the lack of available comparison with a similar population means that we are unable to determine if the TSS is overly sensitive and thereby may lack discrimination. Our finding that the prevalence of TSAs reported by patients with and without LC did not differ may suggest that TSAs are not cancer-specific problems. One underlying reason for TSAs among patients without LC might be oral problems, as these were more frequently reported in combination with TSAs in this patient group. Previous studies of clinically measured taste thresholds in patients with cancer have found altered taste sensitivity in controls with benign diseases [12,13]. Although the clinical testing of taste sensitivity is a different methodology from that used here, our results add to the evidence that TSAs may be related to other pathological processes than cancer.

A suggestive finding of our study, worthy of further research, is that self-reported TSAs were related to weight loss in patients prior to LC treatment. Ovesen et al. [26] also links TSAs to weight loss in their study of clinically measured taste sensitivity. They found no differences in taste sensitivity between newly diagnosed patients with small-cell LC or matched controls with non-malignant diseases. However, patients in both groups who reported weight loss showed abnormal sensitivity for bitter taste.

One question arising from our results, as well as those of Ovesen et al., is whether a causal relationship exists between TSAs and weight loss. Previous research on patients with cancer enrolled in palliative care suggests that TSAs could lead to weight loss by interfering with food intake [9]. In our study on patients prior to treatment, the majority of our sample did not perceive TSAs to interfere with food intake, as instrumentalized by the items “taste funny/no taste” and “smells bother me” on the PG-SGA symptom checklist. Eight patients had marked these items in the PG-SGA, and all had also reported TSAs on the TSS. However, in the eight cases where TSAs were reported to have influenced food intake, this was in conjunction with other symptoms strongly associated with eating problems, i.e. loss of appetite, nausea and early satiety (see also [7]). In previous research in patients with cancer, these symptoms have been found to co-exist with taste change and weight loss in symptom clusters, which are groups of symptoms often experienced simultaneously [11,27]. Loss of appetite, nausea, early satiety, TSAs and weight loss seem to be closely interrelated and it might not be possible to distinguish one of these as the principal symptom driving the process of weight loss. Systemic inflammation has also been recognized as an important factor for the catabolic processes involved in cancer cachexia [7], and could provide important information about the mechanisms behind the association between weight loss and symptoms. Future studies could benefit from including a measure of systemic inflammation to evaluate this connection.

However, it is interesting to note that in our material, many patients did not explicitly make a connection between eating problems, TSAs and weight loss. It could be that food-related problems develop gradually and that it is only when these symptoms severely affect daily life that they are perceived as a problem and articulated by the patient. The different time frames for self-reports should also be kept in mind; weight loss (six months), food intake (one month) and symptoms (two weeks). For example, almost half the patients reporting eating less than usual or ≥ 1 symptom interfering with food intake did not report weight loss ≥ 5%. This might reflect that changes in food intake were relatively recent, and had not yet affected weight. However, close to half of patients categorized as having lost most weight, did not report eating problems. This may suggest that patients had already adapted to a decrease in food intake which occurred earlier in the six-month interval, and had resulted in weight loss.

It is also important to recognize that all patients in our study were under investigation for possible LC, and therefore even those without a LC diagnosis should not be considered a healthy control. It should also be emphasized that this uncertain phase, undergoing investigation for a lethal disease might be stressful, and may affect aspects of daily life, i.e. appetite and eating habits. Compared with the general LC population in Sweden [25], our sample had a larger proportion of women diagnosed with LC (54%), more patients diagnosed in early stages I–IIIA (50% vs. 28.5%), and fewer patients in stage IIIB (6% vs. 22.3%), although the proportion of patients in stage IV reflects the general LC population. This may mean that these patients are less burdened by their disease, and had more energy for study participation. This selection of a “healthier” LC group should be considered when interpreting the results.

In the longitudinal Taste and Smell-project from which these data derive, patients were interviewed rather than given the questionnaires to complete on their own. As interviews involve interaction between interviewer and patient, this strategy may have influenced answers [28], e.g. if patients made efforts to provide socially acceptable responses. However, this interaction also may have positive aspects as establishing a relationship with the patients could have prevented attrition of this vulnerable patient group from the longitudinal study. The face-to-face interviews also provided opportunities to clarify questions when needed and for follow-up when patients gave ambiguous responses.

Conclusion

This study contributes new data showing that TSAs, albeit often relatively mild, are present in a substantive proportion of patients under investigation for LC. TSAs were as frequently reported among patients not diagnosed with LC as among those who received a diagnosis of primary LC. However, an association between weight loss and TSAs was only seen in patients with LC. This relationship could not be fully explained by decreased food intake as a consequence of symptoms interfering with nutritional intake, which highlights the complexity of cancer-related weight loss and the need for further research on this topic.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff at the clinics for recruiting patients to the study, statistician Sara Runesdotter for invaluable advice during data analysis and interpretation of results, research assistant Ylva Hellstadius for assisting with data collection and all patients who generously shared their experiences with us. Economic support was provided by The Swedish Research Council, The Strategic Research Program in Health Care Sciences and The Health Care Science Postgraduate School, Karolinska Institutet.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- 1.Dewys WD, Begg C, Lavin PT, Band PR, Bennett JM, Bertino JR, et al. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American J Med. 1980;69:491–7. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(05)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ross PJ, Ashley S, Norton A, Priest K, Waters JS, Eisen T, et al. Do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for lung cancers? Br J Cancer. 2004;90:1905–11. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nourissat A, Vasson MP, Merrouche Y, Bouteloup C, Goutte M, Mille D, et al. Relationship between nutritional status and quality of life in patients with cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:1238–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooley ME. Symptoms in adults with lung cancer. A systematic research review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19:137–53. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(99)00150-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiss N, Isenring E, Gough K, Krishnasamy M. The prevalence of weight loss during (chemo)radiotherapy treatment for lung cancer and associated patient- and treatment-related factors. Clin Nutr Epub. 2013 Nov 25 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2013.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiss NK, Krishnasamy M, Isenring EA. The effect of nutrition intervention in lung cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy: A systematic review. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66:47–56. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2014.847966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD, Bosaeus I, Bruera E, Fainsinger RL, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: An international consensus. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:489–95. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamper EM, Zabernigg A, Wintner LM, Giesinger JM, Oberguggenberger A, Kemmler G, et al. Coming to your senses: Detecting taste and smell alterations in chemotherapy patients. A systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44:880–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hutton JL, Baracos VE, Wismer WV. Chemosensory dysfunction is a primary factor in the evolution of declining nutritional status and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;33:156–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernhardson BM, Tishelman C, Rutqvist LE. Self-reported taste and smell changes during cancer chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:275–83. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0319-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gift AG, Jablonski A, Stommel M, Given CW. Symptom clusters in elderly patients with lung cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2004;31:202–12. doi: 10.1188/04.ONF.202-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall JC, Staniland JR, Giles GR. Altered taste thresholds in gastro-intestinal cancer. Clin Oncol. 1980;6:137–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamath S, Booth P, Lad TE. Taste thresholds of patients with cancer of the esophagus. Cancer. 1983;52:386–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830715)52:2<386::aid-cncr2820520233>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Williams LR, Cohen MH. Altered taste thresholds in lung cancer. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31:122–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/31.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ovesen L, Sorensen M, Hannibal J, Allingstrup L. Electrical taste detection thresholds and chemical smell detection thresholds in patients with cancer. Cancer. 1991;68:2260–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19911115)68:10<2260::aid-cncr2820681026>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khalid U, Spiro A, Baldwin C, Sharma B, McGough C, Norman AR, et al. Symptoms and weight loss in patients with gastrointestinal and lung cancer at presentation. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:39–46. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0091-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattes RD, Arnold C, Boraas M. Learned food aversions among cancer chemotherapy patients. Incidence, nature, and clinical implications. Cancer. 1987;60:2576–80. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19871115)60:10<2576::aid-cncr2820601038>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGreevy J. Stockholm: Karolinska Institutet; 2013. Characteristics of taste and smell alterations in patients treated for lung cancer: Translation of and results using a symptom-specific questionnaire [Lic. Thesis] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heald AE, Pieper CF, Schiffman SS. Taste and smell complaints in HIV-infected patients. AIDS. 1998;12:1667–74. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199813000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernhardson BM, Olson K, Baracos VE, Wismer WV. Reframing eating during chemotherapy in cancer patients with chemosensory alterations. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:483–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Persson C, Sjoden PO, Glimelius B. The Swedish version of the patient-generated subjective global assessment of nutritional status: gastrointestinal vs urological cancers. Clin Nutr. 1999;18:71–7. doi: 10.1016/s0261-5614(99)80054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer J, Capra S, Ferguson M. Use of the scored Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) as a nutrition assessment tool in patients with cancer. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:779–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Regional Cancer Centre Stockholm Gotland. Clinical care program for Lung Cancer. Vol. 2010 Västerås; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orrevall Y, Tishelman C, Permert J, Cederholm T. Nutritional support and risk status among cancer patients in palliative home care services. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:153–61. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0467-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Swedish Lung Cancer Registry Board. Lung Cancer in Sweden: National Registry for Lung Cancer – Presentation of Material 2002–2009. Uppsala:; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ovesen L, Hannibal J, Sorensen M. Taste thresholds in patients with small-cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clinical Oncol. 1991;117:70–2. doi: 10.1007/BF01613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walsh D, Rybicki L. Symptom clustering in advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:831–6. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0899-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ongena YP, Dijkstra W. A model of cognitive processes and conversational principles in survey interview interaction. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2007;21:145–63. [Google Scholar]