Abstract

Objectives

The present study assessed relationships among social, coping, enhancement, and conformity drinking motives and weekly alcohol consumption by considering drinking identity as a mediator of this relationship.

Methods

Participants were 260 heavy drinking undergraduate students (81% female; Mage = 23.45; SD = 5.39) who completed a web-based survey.

Results

Consistent with expectations, findings revealed significant direct effects of motives on drinking identity for all four models. Further, significant direct effects emerged for drinking identity on weekly drinking. Results partially supported predictions that motives would have direct effects on drinks per week; total effects of motives on drinking emerged for all models but direct effects of motives on weekly drinking emerged for only enhancement motives. There were significant indirect effects of motives on weekly drinking through drinking identity for all four models.

Conclusions

Findings supported hypotheses that drinking identity would mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol consumption. These examinations have practical utility and may inform development and implementation of interventions and programs targeting alcohol misuse among heavy drinking undergraduate students.

Keywords: alcohol, identity, social, coping, enhancement, conformity

Drinking can be examined from a motivational perspective (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; Read, Wood, Kahler, Maddock, & Palfai, 2003) which suggests that individuals drink to enhance or mitigate outcomes (Cox & Klinger, 1988). Health behavior theory indicates that motives are important precursors to behavior (e.g., Edwards, 1954; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1972) and four common drinking motives include: social, coping, enhancement, and conformity (Cooper, 1994). Motives are strongly linked with college drinking (e.g., Abbey, Smith, & Scott, 1993; Foster & Neighbors, 2013; Foster, Neighbors, & Prokhorov, 2014; Maggs & Schulenberg, 1998; Mohr et al., 2005; Schulenberg, O'Malley, Bachman, Wadsworth, & Johnston, 1996). Undergraduates frequently endorse enhancement and social motives, and these are often linked with heavier drinking (LaBrie, Hummer, & Pedersen, 2007; Lewis, Phillippi, & Neighbors 2007). Conformity and coping motives are less frequently reported, but are consistently and more strongly associated with alcohol problems compared to social and enhancement motives (Kuntsche et al., 2005). Motives mediate the effect of alcohol expectancies on use (Williams & Clark, 1998), the effect of social anxiety on negative alcohol consequences (Villarosa, Madson, Zeigler-Hill, Noble, & Morn, 2014), and the effect of bullying on drinking (Archimi & Kuntsche, 2014). Further, motives moderate the effect of ambivalence on drinking (Foster, et al., 2014) and the effect of posttraumatic stress disorder on drinking (Simpson, Stappenbeck, Luterek, Lehavot, & Kaysen, 2014). These associations and strengths thereof depend on motives. Thus, motives are strongly linked with increased drinking, and it is important to better understand this relationship and influencing factors.

One such factor is drinking identity (DI), described as the extent to which alcohol is viewed as a central part of the self (Conner, Warren, Close, & Sparks, 1999). The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991) suggests that alcohol-related attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control conjointly impact intention to drink, which in turn influence alcohol behavior (Ajzen, 1991; Collins & Carey, 2007; Huchting, Lac, & LaBrie, 2008). Predictive validity improves with the incorporation of self-identity (e.g., Charng, Piliavin, & Callero, 1988; Fekadu & Kraft, 2001; Pierro et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2007), conceptualized as the salient part of the self related to a behavior (Conner & Armitage, 1998). Individuals are motivated to maintain consistent self-views (Lalwani & Shavitt, 2009; Steele, 1988), and engaging in identity-relevant behavior facilitates maintenance thereof. As such, alcohol-related identity may be a useful predictor of drinking.

DI has been linked with college drinking (Casey & Dollinger, 2007). Implicitly measured DI reliably and consistently predicts drinking (Foster, Neighbors, & Young, 2014; Gray, Laplante, Bannon, Ambady, & Shaffer, 2011; Lindgren, Foster, Westgate, & Neighbors, 2013a; Lindgren et al., 2013b). Explicit alcohol identity has also been linked with increased drinking (e.g., Reed, Wang, Shillington, Clapp, & Lange, 2007), which in turn is linked with more alcohol problems (e.g., Lindgren et al., 2013a). DI moderates the effect of individualism on alcohol problems (Foster, Yeung, & Quist, 2014), and also the effect of self-control on drinking (Foster, Young, & Barnighausen, 2014). Thus, DI is linked with increased drinking, and likely increases the availability of alcohol in considering from a range of possible behaviors.

It stands to reason that the extent to which alcohol is viewed as part of the self is influenced by motivations for drinking. Moreover, individuals motivated to drink for various reasons may also be likely to drink as a function of viewing alcohol as part of the self. Put simply, it is likely that motives and DI intersect with respect to alcohol outcomes. The importance of drinking motives and DI with respect to alcohol use is clear, particularly among heavy drinking undergraduate populations which are at great risk for undesired or harmful alcohol consequences. As such, DI was examined as a mediator of the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol consumption. Hypotheses were: 1) Motives were expected to have direct effects on DI; 2) Motives were expected to have direct effects on alcohol use; and 3) Motives were expected to have indirect effects on alcohol use via DI.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants included 260 heavy drinking undergraduates (81% female; Mage = 23.45; SD = 5.39). Racial and ethnic distributions were as follows: 49.80% White/Caucasian; 1.19% Native American/American Indian; 13.04% Black/African American; 12.25% Asian; 0.79% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander; 7.51% multi-ethnic; and 15.42% ‘other.’ Further, 34.36% of respondents identified as Hispanic/Latino. Participants had to be at least 18 years of age to be eligible, and met heavy drinking criteria if they reported having consumed four (if female) or five (if male) alcoholic beverages on one occasion in the past month. Recruitment occurred via email and classroom presentations. Participants accessed the survey online and received course extra credit as compensation. All study procedures were conducted in compliance with ethical standards of the American Psychological Association, and the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the study site.

Measures

Demographics

Participants reported race/ethnicity, age, and gender.

Alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins et al., 1985; Kivlahan et al., 1990), measures the number of drinks consumed on each day of the week in the past month. Scores represent the number of drinks consumed each week. Relative to other drinking indices, weekly drinking is a reliable index of problems among undergraduates (Borsari, Neal, Collins, & Carey, 2001). Cronbach's alpha was 0.71. The Quantity/Frequency Scale (Baer, 1993; Marlatt et al., 1995), a 5-item scale, provided an index of heavy drinking. The number of drinks and hours spent drinking on a peak drinking event within the past month. Participants were asked to “Think of the occasion you drank the most this past month” and responded on a scale from 0 to 25+ drinks. Females reporting 4+, and males reporting 5+ drinks were considered heavy drinkers.

Drinking motives

The Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised (Cooper, 1994) was utilized to assess drinking motives. Respondents provided ratings on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (Never/Almost Never) to 5 (Almost Always/Always) regarding 20 reasons why people drink. The measure yields four sub-scales: social (e.g., “Because it helps you enjoy a party”; α = .89), coping (e.g., “To forget your worries”; α = .86), enhancement (e.g., “Because you like the feeling”; α = .86), and conformity (e.g., “Because your friends pressure you to drink”; α = .86).

Drinking identity

DI was assessed using a 5-item measure adapted from the Smoker Self-Concept Scale (Shadel & Mermelstein, 1996) and assessed the degree to which alcohol was integrated with the self-concept via a scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree). An example item is “drinking is a part of ‘who I am.’” Higher mean scores indicated a stronger belief that drinking was part of the self (Lindgren et al., 2013a). The scale was reliable (Lindgren et al., 2013b) and Cronbach's alpha was 0.92.

Results

Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3. The variable for gender was dummy-coded such that females received a 0 and males a 1.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among major variables

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics including means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations. Weekly drinking was marginally correlated with social (r = .12, p <.10) and conformity motives (r = .12, p < .10), but significantly correlated with coping motives (r = .13, p <.05), enhancement motives (r = .27, p <.001), DI (r = .33, p <.001), and gender (r = .24, p <.001). DI was correlated with gender (r = .16, p <.05) and all of drinking motives: social (r = .23, p <.001), coping (r = .34, p <.001), enhancement (r = .33, p <.001), conformity (r = .22, p <.001). All motives were correlated with each other (all p's <.001).

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations among Variables.

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Drinks consumed per week | - | ||||||

| 2. Social drinking motives | 0.12† | - | |||||

| 3. Coping drinking motives | 0.13* | 0.54*** | - | ||||

| 4. Enhancement drinking motives | 0.27*** | 0.71*** | 0.53*** | - | |||

| 5. Conformity drinking motives | 0.12† | 0.34*** | 0.46*** | 0.35*** | - | ||

| 6. Drinking identity | 0.33*** | 0.23*** | 0.34*** | 0.33*** | 0.22*** | - | |

| 7. Gender | 0.24*** | 0.06 | -0.04 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.16* | - |

| Mean | 8.22 | 14.69 | 10.15 | 12.41 | 7.63 | 0.96 | 0.19 |

| Standard Deviation | 7.58 | 4.89 | 4.35 | 4.84 | 3.65 | 1.30 | 0.39 |

| Minimum | 0.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Maximum | 58.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 25.00 | 23.00 | 6.00 | 1.00 |

| Cronbach's alpha | 0.71 | 0.89 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.92 | NA |

Note. N=260 heavy drinking undergraduates.

p < .001

p < .05,

p < .10.

Gender: Male (1), Female (0).

Primary analysis

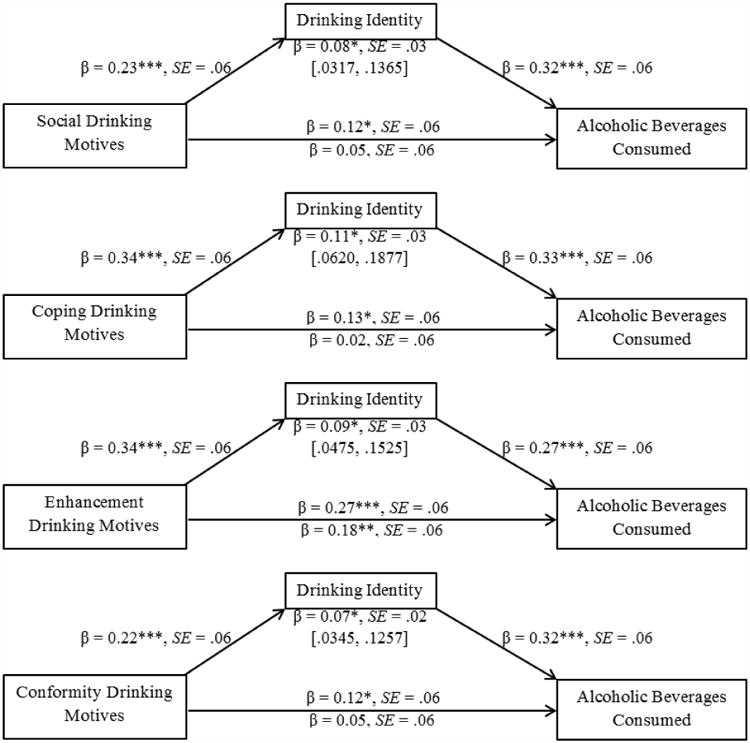

The PROCESS macro, model 4 (Hayes, 2012; 2013) was utilized with 10,000 bootstrap estimates for the construction of 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs; significant if not containing zero). Separate mediation models were constructed for each motive wherein motives influenced weekly drinking directly, as well as indirectly through identity (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mediation models for the relationships among drinking motives (from top to bottom: social, coping, enhancement, and conformity), drinking identity, and weekly alcohol consumption. Standardized path coefficients are presented. Indirect effects and associated standard errors and confidence intervals are presented below the mediator. *** p < .001. ** p < .01. * p < .05.

Social motives

Total effects were significant (effect = .1234, SE = .0618, 95% CI [.0018, .2451]), as were direct effects of social motives on DI (effect = .2326, SE = .0605, 95% CI [.1134, .3518]), direct effects of identity on weekly drinking (effect = .3234, SE = .0604, 95% CI [.2045, .4423]), and indirect effects of social motives on weekly drinking (effect = .0752, SE = .0267, 95% CI [.0320, .1365]).

Coping motives

Total effects were significant (effect = .1343, SE = .0617, 95% CI [.0128, .2558]), as were direct effects of coping motives on DI (effect = .3438, SE = .0585, 95% CI [.2287, .4589]), direct effects of identity on weekly drinking (effect = .3271, SE = .0626, 95% CI [.2039, .4504]), and indirect effects of coping motives on weekly drinking (effect = .1125, SE = .0322, 95% CI [.0615, .1890]).

Enhancement motives

Total effects were significant (effect = .2707, SE = .0599, 95% CI [.1524, .3884]), as were direct effects of enhancement motives on DI (effect = .3361, SE = .0586, 95% CI [.2207, .4516]), direct effects of identity on weekly drinking (effect = .2748, SE = .0614, 95% CI [.1538, .3957]), direct effects of enhancement on drinking (effect = .1780, SE = .0614, 95% CI [.0571, .2990]), and indirect effects of enhancement on drinking (effect = .0924, SE = .0267, 95% CI [.0483, .1541]).

Conformity motives

Total effects were significant (effect = .1224, SE = .0618, 95% CI [.0007, .2441]), as were direct effects of conformity motives on DI (effect = .2256, SE = .0607, 95% CI [.1061, .3450]), direct effects of identity on weekly drinking (effect = .3235, SE = .0603, 95% CI [.2048, .4421]), and indirect effects of conformity on drinking (effect = .0730, SE = .0238, 95% CI [.0342, .1278]).

Discussion

The present research considers DI as a mediator of the relationship between motives and drinking. This further elucidates how the intersection between identity and motives is linked with drinking. Consistent with expectations, findings revealed direct effects of each motive on DI, suggesting that the extent to which an individual drinks for reasons related to social, coping, enhancement, or conformity motives influences how strongly alcohol is viewed as part of the self. Also consistent with predictions, direct effects emerged for DI on weekly drinking, which indicates that those viewing alcohol as part of their self-image likely drink more relative to those who do not. Total effects of motives on drinking emerged the four motives domains; however, direct effects of motives on weekly drinking emerged for only enhancement motives. Enhancement motives are conceptually related to positive reinforcement, and can be described as drinking to enhance a pleasant feeling. Previous research consistently links enhancement motives with problematic drinking (e.g., Leigh & Neighbors, 2009; Palfai, Ralston, & Wright, 2011). Further, enhancement motives have unique relationships with college alcohol behaviors relative to other motives (e.g., Leigh & Neighbors, 2009). This could explain why direct effects emerged for enhancement but not other motives, and indicates that intervention approaches highlighting non-alcohol-related methods for achieving enhanced pleasant feelings may have unique benefit. Also consistent with expectations, indirect effects of motives on weekly drinking through DI emerged for each of the four motives. This indicates that the extent to which an individual views alcohol as part of their identity is an important factor to consider in the relationship between motives and drinking. These findings may have important clinical implications and support the perspective that clinically modifying DI might facilitate breaking the link between motives and drinking. Intervention strategies emphasizing those parts of the identity that are not related to alcohol (e.g., aspects that promote health such as “I am a healthy person”) might have beneficial impact on alcohol outcomes. The present work is consistent with previous research which suggests that DI may be a critical point of intervention and a potential target for clinical and preventative efforts. Strengths of this work must be considered in light of limitations. While cross-sectional, this work represents a logical starting point for further critical examinations of predictive validity. Longitudinal replications are needed to mitigate causal ambiguity.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure: Human Subjects: This study was approved by the instituational review board at the University of Houston.

Contributors: Dawn Foster designed the study, performed literature searches, conducted statistical analysis, drafted the paper, and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest: The author declares that she has no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abbey A, Smith MJ, Scott RO. The relationship between reasons for drinking alcohol and alcohol consumption: An interactional approach. Addictive Behaviors. 1993;18(6):659–670. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(93)90019-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 1991;50:179–211. [Google Scholar]

- Archimi A, Kuntsche E. Do offenders and victims drink for different reasons? Testing mediation of drinking motives in the link between bullying subgroups and alcohol use in adolescence. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39(3):713–716. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer JS. Etiology and secondary prevention of alcohol problems with young adults. In: Baer J, Marlatt G, McMahon R, Baer J, Marlatt G, McMahon R, editors. Addictive behaviors across the life span: Prevention, treatment, and policy issues. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1993. pp. 111–137. [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Neal DJ, Collins SE, Carey KB. Differential utility of three indexes of risky drinking for predicting alcohol problems in college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15:321–324. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey PF, Dollinger SJ. College students' alcohol-related problems: An autophotograpic approach. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education. 2007;51(2):8–25. [Google Scholar]

- Charng H, Piliavin JA, Callero PL. Role identity and reasoned action in the prediction of repeated behavior. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1988;51(4):303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Collins R, Parks GA, Marlatt G. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins SE, Carey KB. The theory of planned behavior as a model of heavy episodic drinking among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):498–507. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Armitage CJ. Extending the theory of planned behaviour: A review and avenues for further research. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:1430–1464. [Google Scholar]

- Conner M, Warren R, Close S, Sparks P. Alcohol consumption and the theory of planned behaviour: An examination of the cognitive mediation of past behaviour. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1999;29:1675–1703. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Farmer NM, Nolen-Hoekesma S. Relations among stress, coping strategies, coping motives, alcohol consumption and related problems: A mediated moderation model. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(4):1912–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox W, Klinger A. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards W. The theory of decision making. Psychological Bulletin. 1954;51(4):380–417. doi: 10.1037/h0053870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekadu Z, Kraft P. Self-identity in planned behavior perspective: Past behavior and its moderating effects on self-identity–intention relations. Social Behavior and Personality. 2001;29(7):671–685. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Attitudes and opinions. Annual Review of Psychology. 1972:487–544. [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Neighbors C. Self-consciousness as a moderator of the effect of social drinking motives on alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(4):1996–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Neighbors C, Prokhorov A. Drinking motives as moderators of the effect of ambivalence on drinking and alcohol-related problems. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Neighbors C, Young C. Drink refusal self-efficacy and implicit drinking identity: An evaluation of moderators of the relationship between self-awareness and drinking behavior. Addictive Behaviors. 2014;39:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Young CM, Barnighausen TW. Self-control as a moderator of the relationship between drinking identity and alcohol use. Substance Use and Misuse. 2014:1–9. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2014.901387. early online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster DW, Yeung N, Quist MC. The influence of individualism and drinking identity on alcohol problems. International Journal of Mental health and Addiction. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s11469-014-9505-2. early online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray HM, LaPlante DA, Bannon BL, Ambady N, Shaffer HJ. Development and validation of the alcohol identity implicit associations test (AI-IAT) Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(9):919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling. 2012 [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Huchting K, Lac A, LaBrie JW. An application of the theory of planned behavior to sorority alcohol consumption. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(4):538–551. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlahan DR, Marlatt GA, Fromme K, Coppel DB, Williams E. Secondary prevention with college drinkers: Evaluation of an alcohol skills training program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:805–810. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.58.6.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER. Reasons for drinking in the college student context: The differential role and risk of the social motivator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):393–398. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani AK, Shavitt S. The “me” I claim to be: Cultural self-construal elicits self-presentational goal pursuit. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(1):88–102. doi: 10.1037/a0014100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J, Neighbors C. Enhancement motives mediate the positive association between mind/body awareness and college student drinking. Journal Of Social And Clinical Psychology. 2009;28(5):650–669. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2009.28.5.650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Phillippi J, Neighbors C. Morally based self-esteem, drinking motives, and alcohol use among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):398–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Foster DW, Westgate EC, Neighbors C. Implicit drinking identity: Drinker + me associations predict college student drinking consistently. Addictive Behaviors. 2013a;38(5):2163–2166. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren KP, Neighbors C, Teachman BA, Wiers RW, Westgate E, Greenwald AG. I drink therefore I am: Validating alcohol-related implicit association tests. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013b;27:1–13. doi: 10.1037/a0027640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg J. Reasons to drink and not to drink: Altering trajectories of drinking through an alcohol misuse prevention program. Applied Developmental Science. 1998;2(1):48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G, Baer JS, Larimer M. Preventing alcohol abuse in college students: A harm-reduction approach. In: Boyd GM, Howard J, Zucker RA, editors. Alcohol problems among adolescents: Current directions in prevention research. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1995. pp. 147–172. [Google Scholar]

- Mohr CD, Armeli S, Tennen H, Temple M, Todd M, Clark J, et al. Moving beyond the key party: A daily process study of college student drinking motivations. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2005;19:392–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.4.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palfai TP, Ralston TE, Wright LL. Understanding university student drinking in the context of life goal pursuits: The mediational role of enhancement motives. Personality And Individual Differences. 2011;50(2):169–174. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.09.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pierro A, Mannetti L, Livi S. Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior in the prediction of health behavior and leisure activity. Self and Identity. 2003;2(1):47–60. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17:13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MB, Wang R, Shillington AM, Clapp JD, Lange JE. The relationship between alcohol use and cigarette smoking in a sample of undergraduate college students. Addict Behaviors. 2007;32(3):449–464. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Wadsworth KN, Johnston LD. Getting drunk and growing up: Trajectories of frequent binge drinking during the transition to young adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57(3):289–304. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadel WG, Mermelstein R. Individual differences in self-concept among smokers attempting to quit: Validation and predictive utility of measures of the smoker self-concept and abstainer self-concept. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1996;18(3):151–156. doi: 10.1007/BF02883391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JR, Terry DJ, Manstead ASR, Louis WR, Kotterman D, Wolfs J. Interaction effects in the theory of planned behavior: The interplay of self-identity and past behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2007;37(11):2726–2750. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Lehavot K, Kaysen DL. Drinking motives moderate daily relationships between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123(1):237–247. doi: 10.1037/a0035193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM. The psychology of self-affirmation: Sustaining the integrity of the self. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 21. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1988. pp. 261–302. [Google Scholar]

- Villarosa MC, Madson MB, Zeigler-Hill V, Noble JJ, Mohn RS. Social Anxiety Symptoms and Drinking Behaviors Among College Students: The Mediating Effects of Drinking Motives. Psychology Of Addictive Behaviors. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0036501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams A, Clark D. Alcohol consumption in university students: The role of reasons for drinking, coping strategies, expectancies, and personality traits. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23(3):371–378. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)80066-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]