Abstract

Purpose of review

Echinocandin resistance in Candida is a great concern, as the echinocandin drugs are recommended as 1st line therapy for patients with invasive candidiasis. Here we review recent advances in our understanding of the epidemiology, underlying mechanisms, methods for detection and clinical implications.

Recent findings

Echinocandin resistance has emerged over the recent years. It has been found in most clinically relevant Candida species, but is most common in C. glabrata with rates exceeding 10% at selected institutions. It is most commonly detected after 3–4 weeks of treatment and is associated with a dismal outcome. An extensive list of mutations in hot-spot regions of the genes encoding the target has been characterised and associated with species and drug specific loss of susceptibility. The updated antifungal susceptibility testing reference methods identify echinocandin resistant isolates reliably; while the performance of commercial tests is somewhat more variable. Alternative technologies are being developed including molecular detection and MALDI-TOF.

Summary

Echinocandin resistance is an increasingly encountered and mandates susceptibility testing particularly in patients with prior exposure. The further development of rapid and user-friendly commercially available susceptibility platforms is warranted. Antifungal stewardship is important in order to minimise unnecessary selection pressure.

Keywords: echinocandins, Candida, FKS hot spot mutation, epidemiology

Introduction

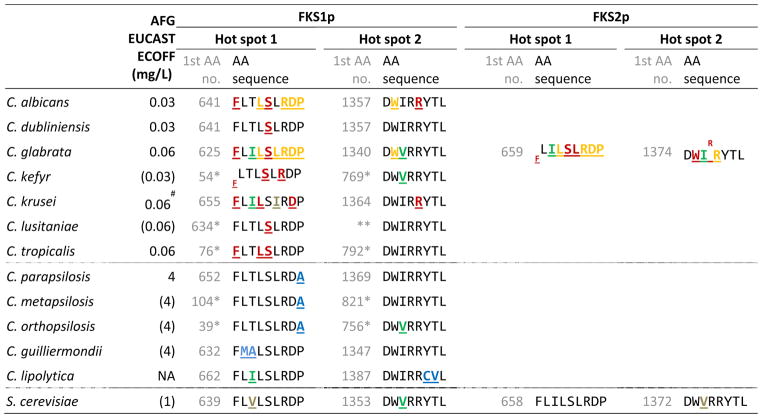

The three echinocandins, anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin, have been available for a decade. They display in vitro fungicidal activity against most Candida species, attractive tolerability and pharmacokinetic profiles, and have been recommended as first line agents for invasive candidiasis (1–6). The echinocandins exhibit their antifungal activity via inhibition of the enzyme glucan synthase encoded by three related genes (FKS1, FKS2 and FKS3). Most Candida species are considered good targets. However, some Candida spp. are inherently less susceptible in vitro due to naturally occurring polymorphisms in the target protein (Table 1) (7). For example, the echinocandin MIC is approx. 7-fold higher against C. parapsilosis, which has a naturally occurring alteration in the target gene (Table 1). Following regulatory approval, the use of the echinocandins for prophylaxis and treatment has grown substantially. A consequence of enhanced drug exposure is increased selection pressure for resistance and indeed an altered species distribution for invasive infections has been linked to the echinocandin use (8). Moreover, reports on acquired echinocandin resistance, defined as resistance among species that are normally susceptible, have emerged and today acquired resistance has been reported in single isolates belonging to most Candida species including C. albicans, C. dubliniensis, C. kefyr, C. glabrata, C. krusei, C. lusitaniae and C. tropicalis (9–15). Elevated MICs have been associated with a number of single amino acid (AA) substitutions caused by mutations in specific “hot spot” regions of the well conserved target genes FKS1 for all Candida spp., as well as FKS2 for C. glabrata (Table 1)(16). The position, as well as, the specific AA substitution determines the degree of MIC elevation in the individual isolate.

Table 1.

FKS amino acid (AA) sequences and ECOFFs for 12 wild type Candida species and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. AA alterations are underlined and in bold font with a colour indication of origin of the mutation and impact on the MIC (as explained in detail in the footnote).

|

“strong R” mutation,

“strong R” mutation,

indicate the codon involves a mutation or deletion;

indicate the codon involves a mutation or deletion;

indicate the codon involves a mutation or stop codon;

indicate the codon involves a mutation or stop codon;

“weak R” mutation;

“weak R” mutation;

“silent” mutation, acquired or naturally occurring;

“silent” mutation, acquired or naturally occurring;

naturally occurring mutation proven or possibly related to the intrinsic lower susceptibility;

naturally occurring mutation proven or possibly related to the intrinsic lower susceptibility;

naturally occurring mutation of unknown impact;

naturally occurring mutation of unknown impact;

Inaccurate annotation, sequencing of entire gene-sequence required;

Micafungin ECOFF elevated for C. krusei compared to C. albicans and C. glabrata, but not the anidulafungin ECOFF.

The aim of this review is to present an up to date overview of echinocandin resistance in Candida by addressing the current epidemiology, the underlying molecular mechanisms and their differential impact on susceptibility and fitness, methods for resistance detection and the potential implication of increasing echinocandin resistance on treatment strategies of invasive candidiasis.

Epidemiology

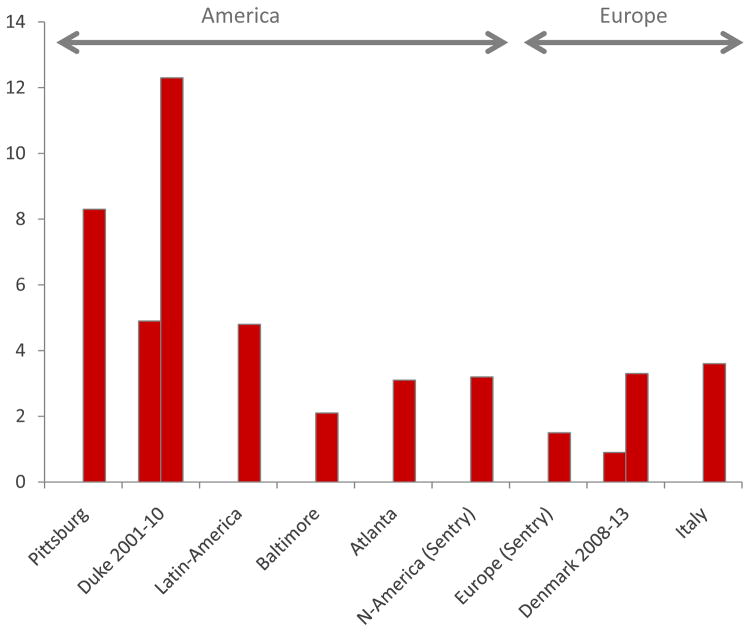

Quite soon after the introduction of the echinocandins it was noted that the increasing use was accompanied by epidemiological shifts with a proportional or numeric increase in the less susceptible C. parapsilosis at several centres (8;17;18). Subsequently, the number of reports of acquired echinocandin resistance has attracted attention. Most are case reports or case series, which collectively document the potential of resistance development in almost all species that are not intrinsically susceptible (9–15). Although some cases are reported after short-term use (a week)(13;19), most cases are diagnosed after 3–4 weeks of therapy or even later (12;20;21). Resistance is more often found in C. glabrata, although this species is less frequent than C. albicans as a cause of invasive infections and has been reported on both sides of the Atlantic ocean (Fig 1) (21;22). Whether this is due to a higher potential for developing resistance mutations or it relates to patients with C. glabrata infections who more often receive prolonged echinocandin therapy due to the intrinsic reduced susceptibility to azoles like fluconazole remains to be understood. Nevertheless, resistance in C. glabrata is on the rise. This was recently documented in a 10-year survey at the Duke University hospital where the echinocandin resistance rate increased from 4.9% to 12.3% in 2001–10 (23). A similar trend has been observed in the nation-wide fungaemia survey in Denmark, although on a smaller scale. Here, no cases were found in 2004–7, whilst 0.9% of the C. glabrata blood stream infections involved resistant isolates in 2008–9, 1.2% in 2010–11 and 3.1% resistance in 2012–13 (Arendrup, unpublished observations). Of note, resistance figures observed in fungaemia surveillance programmes may underestimate the true number of such cases, since only the initial blood isolate is included to avoid biasing the data set, which is sound from an epidemiological point of view. Notably, it was recently reported that echinocandin resistance was detected in as many as 10% of post treatment oral mucosal isolates obtained from candidaemic patients initially treated with an echinocandin (24).

Fig. 1.

Echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata in Europe and America. Proportion of invasive isolate with resistance at tertiary centres (Pittsburgh, Duke and 7 Latin American hospitals), Shields AAC 2013; Alexander CID 2013; Nucci Plos One 2013; In population based surveys (Baltimore, Atlanta, Denmark) and Italy and from the global sentry study. Zimbeck AAC 2010; Pfaller JCM 2011; Arendrup Unpubl data; Tortorano Infection 2013.

The use of echinocandins as 1st line agents for candidaemia has unquestionably improved outcome for patients infected with a susceptible isolate (1). However, there is solid documentation that the outcome for patients with increased MICs is significantly poorer. Not only has an unsuccessful outcome been reported in most case reports, but it was also documented in two recent studies that 80% and 78.5% candidaemia patients with an echinocandin resistant C. glabrata isolate fail therapy, respectively (23;25).

Mechanisms and impact of the MIC

Intrinsic target gene alterations are found in C. parapsilosis, C. metapsilosis, C. orthopsilosis, C. guilliermondii and C. lipolytica (Table 1) (7;26). Additionally, polymorphisms occur at codon I660 in hot spot 1 of FKS1 in C. krusei, for which the in vitro micafungin MIC is elevated approx. 2-fold and at codon V641 in FKS1 and V1374 in FKS2 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which is in general slightly less echinocandin susceptible than C. albicans and C. glabrata. The potential impact of these polymorphisms for therapeutic response remains unclear (Table 1).

Acquired FKS alterations are most commonly substitutions, but deletions and stop codons have also been reported in C. glabrata (Table 1) (16;21). The degree of the MIC elevation depends on the position as well as the specific AA substitution. The most significant MIC elevation is found for alterations involving the 1st and 5th AA(F (phenylalanine) and S (serine)), respectively in the hot spot 1 regions of the FKS1 or FKS2 target genes (Table 1 and 2). FKS alterations in most cases confer cross-resistance to all three echinocandins. However, some alterations cause more moderate MIC elevations and not always for all three compounds (Table 2). For example, the F659-DEL in C. glabrata confers resistance to all three echinocandins, whereas the F659S substitution at the same codon gives rise to anidulafungin and caspofungin resistance, whereas the micafungin MIC and in vivo efficacy in a murine animal model remains unchanged (23;25;27–30). Finally, the MIC increase caused by a specific alteration may be species specific. Thus, the echinocandin MICs were elevated at least 5-foldabove the breakpoints for C. krusei harbouring the D662Y compared to 1-foldabove the breakpoint for C. albicans and an MIC below the breakpoint for C. glabrata harbouring the corresponding alterations (D648Y in C. albicans and D666Y in the Fks2p protein for C. glabrata)(20;28).

Table 2.

Anidulafungin, caspofungin and micafungin MIC elevation for specific hot-spot 1 Fks2p alterations in C. glabrata.

| FKS alteration | MIC (mg/L)

|

Dilution steps above the BP*

|

Method, Reference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anidulafungin | Caspofungin | Micafungin | Anidulafungin | Caspofungin | Micafungin | ||

| F659 | |||||||

| F659-DEL | 0.12–0.5 | 0.5–1a | 0.06–0.5 | 1–3 | 2–3a | 2–4 | EUCAST/Etesta, Arendrup unpublished data |

| ND | 8 | ND | - | 6 | - | CLSI, Shields AAC 2013 | |

| 1 | >8 | 2 | 4 | >6 | 5 | CLSI, Alexander CID 2013 | |

|

| |||||||

| F659V | 1 | 2–8 | 0.12–0.25 | 3 | 4–6 | 1–2 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 |

| 1 | 2–4 | 0.25 | 3 | 4–5 | 2 | CLSI, Alexander CID 2013 | |

|

| |||||||

| F659Y | 1 | 1–2 | 0.12–0.25 | 3 | 2–4 | 1–2 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 |

| 0.5–1 | 0.5–2 | 0.25 | 2–3 | 2–4 | 2 | CLSI, Pham AAC 2014 | |

|

| |||||||

| F659L | ND | 1–2 | ND | - | 3–4 | - | CLSI, Shields AAC 2013 |

|

| |||||||

| F659S | 0.12–0.5 | 0.5–2a | 0.03 | 1–3 | 2–4a | 0 | EUCAST/Etesta, Arendrup unpublished data |

| 0.25–1 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.06 | 1–3 | 1–2 | 0 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 | |

| 2 | 2 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | 2 | CLSI, Pham AAC 2014 | |

|

| |||||||

| L662W | 1–2 | 0.5–1 | 0.25–0.5 | 3–4 | 2–4 | 2–4 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 |

|

| |||||||

| S663 | |||||||

| S663P | 0.25–2 | >32a | 0.12–1 | 2–5 | >8 | 2–4 | EUCAST/Etesta, Arendrup unpublished data |

| 1–4 | 1–16 | 0.25–4 | 3–5 | 3–7 | 2–6 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 | |

| ND | 0.5–8b | ND | - | 2–6 | - | Yeast one, Beyda CID 2014 | |

| 0.5–4 | 1–>16 | 0.5–4 | 2–5 | 2–>7 | 3–6 | CLSI, Pham AAC 2014 | |

| 1–4 | 0.5–>8 | 0.12–>8 | 3–5 | 2–>6 | 1–>7 | CLSI, Alexander CID 2013 | |

|

| |||||||

| S663Y | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 |

|

| |||||||

| S663F | 0.12–1 | 0.5a | ND | 1–4 | 2 | - | EUCAST/Etesta, Arendrup unpublished data |

| 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.12 | 2 | 1 | 1 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 | |

| ND | 0.25 | ND | - | 1 | - | Yeast one, Beyda CID 2014 | |

| 0.5–2 | 0.25–2 | 0.12–0.25 | 2–4 | 1–4 | 1–2 | CLSI, Pham AAC 2014 | |

|

| |||||||

| L664R | 1 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.25 | 3 | 1–2 | 2 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 |

|

| |||||||

| R665S | 0.12 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 0 | 2 | 1 | CLSI, Alexander CID 2013 |

|

| |||||||

| R665G | 0.25 | 0.5 | 0.12 | 1 | 2 | 1 | CLSI, Alexander CID 2013 |

|

| |||||||

| D666Y | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.06 | 0 | 1 | 0 | CLSI, Castanheira AAC 2014 |

|

| |||||||

| D666G | 1 | 2 | 0.12 | 4 | 4 | 2 | EUCAST, Arendrup unpublished data |

|

| |||||||

| D666E | 0.25 | 2 | 0.06 | 2 | 4 | 1 | EUCAST, Arendrup unpublished data |

|

| |||||||

| P667 | |||||||

| P667T | 0.25 | ND | 0.03 | 2 | - | 0 | EUCAST/Etesta, Arendrup unpublished data |

| 1 | 1 | 0.12 | 3 | 3 | 1 | CLSI, Alexander CID 2013 | |

|

| |||||||

| P667H | 2 | 2 | 0.25 | 4 | 4 | 2 | CLSI, Pham AAC 2014 |

the echinocandin clinical breakpoints BPs applied are those for the specific reference method used and are as follows: EUCAST MIC testing: anidulafungin S: ≤ 0.06 mg/L, micafungin S: ≤ 0.03 mg/L and CLSI MIC testing: anidulafungin: S: ≤ 0.125 mg/L, caspofungin: S: ≤ 0.125 mg/L and micafungin S: ≤ 0.06 mg/L.

EUCAST BPs have not yet been established for caspofungin, hence caspofungin susceptibility testing was done using Etest and applying the CLSI breakpoints as recommended by the manufacturer.

Implication on fitness

Resistance mutations often come at a fitness cost and when that is the case, it may limit the spread of the organism due to competition from wild type isolates when therapy is discontinued. Echinocandin resistance in Candida has been linked to loss of fitness for homozygous Fks1p F641 and S645 mutants of C. albicans and Fks2p S663P mutants of C. glabrata (31–33). Thus, mutations at these hot spots have been linked to a) impaired enzyme capacity, b) altered cell wall composition, i.e. reduced glucan and increased chit in content, c) increased cell wall thickness and d) impaired filamentation properties, which contribute to a lower growth rate in vitro and in vivo in drosophila and mouse models (31–33). Similarly, Lackner et al found reduced kidney burden comparing sequential C. albicans clinical isolates with and without two heterogenous mutations simultaneously at position R647 and P649 (34). In contrast, Borghi et al found no significant difference in virulence or fitness when comparing sequential patient C. glabrata isolates with and without the S663P mutation in the Galleria mellonella larvae model (35). Either, this contradictory finding relates to the different virulence models used, i.e. larvae versus mouse models, or alternatively, it may be explained by differences in the fitness reduction in the two isolates investigated in these studies. Indeed, whole genome sequencing of a series of clinical C. glabrata isolates revealed that a subsequent compensatory mutation (CDC55 P155S) mitigated the fitness cost induced by the S663P mutation (32).

Detection of resistance

Detection of echinocandin resistance can be assessed phenotypically, using microbroth dilution, Etest or disk diffusion or semi-automated systems like the VITEK system or it can be done molecularly by detection of mutations in the hot spot regions of the FKS1 and FKS2 (C. glabrata only) genes. Additionally, preliminary studies have exploited the adoption of MALDI-TOF for resistance detection. These options and comments regarding pros and cons will be discussed below.

Microdilution Reference testing and commercial phenotypic susceptibility tests

The two organisations EUCAST and CLSI both have established reproducible and reliable microbroth dilution susceptibility tests for Candida and echinocandins (36–38). Besides being the reference method commercial susceptibility tests are standardised against, these reference methods have proven reliable and useful in mycology reference laboratories for the detection of resistance in referred clinical isolates. Recently, EUCAST breakpoints were developed for anidulafungin and micafungin and the former CLSI breakpoints were revised providing species specific breakpoints for all three echinocandins and their value confirmed (28;39–42). Despite this, some laboratories have noted an unexpected high number of C. glabrata and C. krusei isolates being categorised as non-susceptible using the CLSI method for testing caspofungin susceptibility and by using the Etest and Sensititre Yeast One system, which are standardised against the CLSI method (29;43–45). Thus, almost 20% of C. glabrata isolates and more than a third of the C. krusei isolates were anidulafungin and micafungin susceptible but caspofungin non-susceptible (44;45). This may in part be associated with variability in the caspofungin used for in vitro testing (46). Consequently, anidulafungin and micafungin have been evaluated as markers for caspofungin susceptibility and found appropriate for this purpose and is recommended also by EUCAST (40;47;48). The Sensititre Yeast One system was recently evaluated in a multicentre study using consecutive samples received in each of eight laboratories. Overall a good inter laboratory agreement was achieved and the resistance rates reported for anidulafungin and micafungin was within the expected range (4.3 and 4.4% for anidulafungin and micafungin, respectively) (45).

Few studies have systematically evaluated the commercial susceptibility test systems for their ability to correctly discriminate between susceptible wild type isolates and those bearing FKS resistance mutations by including a sufficient number of mutant isolates. In one such study evaluating the performance the VITEK system for caspofungin susceptibility, a relatively high number (19.4%) of mutant isolate were mis-classified as susceptible (49). This finding coupled with the fact that the system could not discriminate intermediate from susceptible C. glabrata isolates because the caspofungin concentration used in the system does not encompass the breakpoint, renders it less useful in its current form despite being very user friendly. Hence, although commercial testing has become available for most antifungal compounds including the echinocandins, some challenges remain to be addressed. Therefore, any laboratory wishing to perform antifungal susceptibility testing using one of these systems must assure that the MIC values generated for wild type isolates match the wild type distributions used for the clinical breakpoint setting, before adopting the reference breakpoints (38).

Molecular approaches

So far, clinically relevant acquired echinocandin resistance in Candida has never been detected in absence of FKS hot spot mutations. Hence, an attractive approach is to apply molecular tools for echinocandin resistance detection. Target gene sequencing has become increasingly available and appropriate primers designed and published for the most common species (9–15). The drawback, however, is the associated cost and it is time consuming unless automated. Various PCR formats focussing specifically on the detection of mutations in C. glabrata have been developed (50;51). The obvious benefit of such assays is that they allow a rapid detection of resistance in the species where resistance most often occur. The challenges are that a correct identification to the species level is required for selection of appropriate methodology and that knowledge regarding the species and compound dependent differential impact on the susceptibility is required to separate mutations associated with therapeutic failure from those that may respond to one or several echinocandins. Finally, none of these methods is yet commercially available and therefore implementation requires molecular biology expertise and in house validation.

Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF)

Recently, the potential of using MALDI-TOF detection of proteome changes after a 15-h exposure of fungal cells to serial drug concentrations was described for the determination of antifungal susceptibility (52). It was followed by a simplified version, which facilitated discrimination of susceptible and resistant isolates of C. albicans after only 3 hours of incubation in the presence of two “breakpoint” level drug concentrations (0.03 and 32 mg/L) of caspofungin (53). Categorizations determined using MALDI-TOF MS-based AFST (ms-AFST) were consistent with the wild-type and mutant FKS1 genotypes and the AFST reference methodology. Although it remains to be investigated how this approach can be extended to include other species with different growth kinetics and species specific clinical breakpoints, the prospect of a “same-day” susceptibility screening test is indeed attractive.

Clinical implications

The increasing incidence of echinocandin resistant Candida isolates is a reason for concern, as it is leading to the emergence of multidrug resistant organisms that present limited, if any, treatment options. This is particularly true for the emergence of echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata, an organism that is commonly resistant to azole drugs and for which amphotericin B is therefore the only therapeutic alternative. Echinocandin resistance often develop in a progressive manner. Resistant isolates can be detected in the oral flora post candidaemia treatment at a rate of approx. 10% often in co-existence with susceptible isolates but is detected at a lower rate and apparently typically later (3–4 weeks) among blood isolates (12;21;24). Unlike the azoles, echinocandins are not used in the primary health care sector or for plant and material protection. Therefore, antifungal stewardship in the hospital is of utmost importance in order to minimise the selection pressure when possible. A step down approach has been recommended in the new ESCMID guidelines for the management of invasive candidiasis (2–5). Based upon the data from initial controlled trial, ESCMID recommended de-escalation after 10 days, as data was not available supporting any earlier time-point (54). Recently, early step-down after 5 days of echinocandin therapy was found efficacious in an open-label study in patients meeting the prespecified criteria (ability to tolerate oral therapy; afebrile for > 24 hours; hemodynamically stable; not neutropenic; and with a documented clearance of Candida from the bloodstream) (55). This may suggest that early de-escalation is a reasonable approach at least in this category of patients. It is well recognised, that the clinical situation may mandate longer treatment and that voriconazole or high dose fluconazole may not be attractive alternatives in severely ill patients with C. glabrata candidaemia. Careful monitoring for antifungal resistance in invasive and colonising samples should be performed when echinocandin therapy is prescribed for longer time periods. Moreover, strategies involving alternating therapy (echinocandin and amphotericin B) or periods with combination therapy might potentially be alternative options that deserve further investigation.

Conclusion

Echinocandin resistance is emerging in population based candidaemia surveys and particularly in severely ill patients receiving longer-term therapy. It is particularly challenging with C. glabrata where the alternative treatment options are limited. The outcome for patients with resistant isolates on echinocandin therapy is dismal. Therefore, early detection is mandatory. Antifungal susceptibility testing has been optimised over the recent years and should be available real time for centres managing high-risk patients. However, further work is needed in order to optimise susceptibility testing in the routine setting using commercial test formats. New modalities including molecular and MALDI-TOF detection are under development and appear promising for future implementation in clinical microbiology laboratories. Antifungal stewardship is an important tool reducing unnecessary use and the treatment duration whenever clinically indicated may help reducing the selection pressure and thus reverting the rise in resistance. Potentially, strategies involving alternating or combination therapy might deserve clinical evaluation for patients requiring long term antifungal treatment with Candida coverage in order to avoid selection of resistance to this important drug class.

Key points.

Echinocandin resistance in Candida is emerging in most clinically relevant Candida species but is particularly common in C. glabrata

A wide range of hot spot mutations in the FKS target genes have been characterised and their impact on MIC and fitness described

Reference antifungal susceptibility testing can reliably identify resistant isolates

New methodologies include molecular techniques and MALDI-TOF are being developed for detection of resistant isolates

Antifungal stewardship including efforts to limit long term echinocandin exposure is recommended

Acknowledgments

No funding or other support was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Maiken Cavling Arendrup is on the global advisory board for Merck and has received research grants, honoraria as speaker and for acting as a consultant for Astellas, Gilead, and Pfizer.

David S Perlin is supported by grants from the NIH and Astellas. He also has a recently issued patent on detection of echinocandin resistance.

References

- 1.Andes DR, Safdar N, Baddley JW, et al. Impact of treatment strategy on outcomes in patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: a patient-level quantitative review of randomized trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Apr;54(8):1110–22. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuenca-Estrella M, Verweij PE, Arendrup MC, et al. ESCMID* Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candida Diseases 2012: Diagnostic Procedures. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(Suppl 7):9–18. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, et al. ESCMID* Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candida Diseases 2012: Non-Neutropenic Adult Patients. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(Suppl 7):19–37. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hope WW, Castagnola E, Groll AH, et al. ESCMID* Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candida Diseases 2012: Prevention and Management of Invasive Infections in Neonates and Children Caused by Candida spp. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(Suppl 7):38–52. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullmann AJ, Akova M, Herbrecht R, et al. ESCMID* Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Candida Diseases 2012: Adults with Haematological Malignancies and after Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (HCT) Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 2012;18(Suppl 7):53–67. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Mar 1;48(5):503–35. doi: 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garcia-Effron G, Katiyar SK, Park S, et al. A naturally occurring proline-to-alanine amino acid change in Fks1p in Candida parapsilosis, Candida orthopsilosis, and Candida metapsilosis accounts for reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Jul;52(7):2305–12. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00262-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lortholary O, Desnos-Ollivier M, Sitbon K, et al. Recent exposure to caspofungin or fluconazole influences the epidemiology of candidemia: a prospective multicenter study involving 2,441 patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Feb;55(2):532–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01128-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park S, Kelly R, Kahn JN, et al. Specific substitutions in the echinocandin target Fks1p account for reduced susceptibility of rare laboratory and clinical Candida sp. isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005 Aug;49(8):3264–73. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.8.3264-3273.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cleary JD, Garcia-Effron G, Chapman SW, Perlin DS. Reduced Candida glabrata susceptibility secondary to an FKS1 mutation developed during candidemia treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Jun;52(6):2263–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01568-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desnos-Ollivier M, Bretagne S, Raoux D, et al. Mutations in the fks1 gene in Candida albicans, C. tropicalis and C. krusei correlate with elevated caspofungin MICs uncovered in AM3 medium using the EUCAST method. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008 Jun 30;52:3092–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00088-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen RH, Johansen HK, Arendrup MC. Stepwise Development of a Homozygous S80P Substitution in Fks1p, Conferring Echinocandin Resistance in Candida tropicalis. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013 Jan 1;57(1):614–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01193-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fekkar A, Meyer I, Brossas JY, et al. Rapid Emergence of Echinocandin Resistance during Candida kefyr Fungemia Treatment with Caspofungin. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013 May 1;57(5):2380–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02037-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Desnos-Ollivier M, Moquet O, Chouaki T, et al. Development of echinocandin resistance in Clavispora lusitaniae during caspofungin treatment. J Clin Microbiol. 2011 Jun;49(6):2304–6. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00325-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arendrup MC, Garcia-Effron G, Lass-Florl C, et al. Echinocandin susceptibility testing of Candida species: comparison of EUCAST EDef 7.1, CLSI M27-A3, Etest, disk diffusion, and agar dilution methods with RPMI and isosensitest media. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 Jan;54(1):426–39. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01256-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perlin DS. Resistance to echinocandin-class antifungal drugs. Drug Resist Updat. 2007 Jun;10(3):121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sipsas NV, Lewis RE, Tarrand J, et al. Candidemia in patients with hematologic malignancies in the era of new antifungal agents (2001–2007): stable incidence but changing epidemiology of a still frequently lethal infection. Cancer. 2009 Oct 15;115(20):4745–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forrest GN, Weekes E, Johnson JK. Increasing incidence of Candida parapsilosis candidemia with caspofungin usage. J Infect. 2008 Feb;56(2):126–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2007.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lewis JS, Wiederhold NP, Wickes BL, et al. Rapid Emergence of Echinocandin Resistance in Candida glabrata Resulting in Clinical and Microbiologic Failure. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013 Sep 1;57(9):4559–61. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01144-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.Jensen RH, Justesen US, Rewes A, et al. Echinocandin Failure Case Due to a Previously Unreported FKS1 Mutation in Candida krusei. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Jun;58(6):3550–2. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02367-14. First description of the D660Y alteration in C. krusei and a head to head comparison with the corresponding mutation in C. albicans showing how a specific alteration lead to different MIC alteration in two species. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dannaoui E, Desnos-Ollivier M, Garcia-Hermoso D, et al. Candida spp. with acquired echinocandin resistance, France, 2004–2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2012 Jan;18(1):86–90. doi: 10.3201/eid1801.110556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto E, Boyken L, Tendolkar S, et al. Candidemia surveillance in Iowa: emergence of echinocandin resistance. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease. 2014 Jun;79(2):205–8. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **23.Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Pfeiffer CD, et al. Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin Infect Dis. 2013 Jun;56(12):1724–32. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit136. First comprehensive overview of documented increasing echinocandin resistance rates in C. glabrata. Rates exceeding 10% is described and a significant proportion were multidrug resistant with high azole MICs. MICs for each isolate is presented together with the specific target gene alterations. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **24.Jensen RH, Johansen HK, Søes LM, et al. Post-treatment antifungal resistance among colonising Candida isolates in candidaemia patients: preliminary results from a systematic multi-centre study. 2014 May 10;2014:45. Preliminary data demonstrating a notably high prevalence of echinocandin resistance (9.2%) in oral isolates from patients after treatment for candidaemia, demonstrating a higher potential for rapid resistance selection than presented in epidemiological candidaemia studies where only initial isolates are included. [Google Scholar]

- **25.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Caspofungin MICs Correlate with Treatment Outcomes among Patients with Candida glabrata Invasive Candidiasis and Prior Echinocandin Exposure. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2013 Aug 1;57(8):3528–35. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00136-13. Elegant demonstration of the correlation between caspofungin MIC and outcome, but also of the fact that the revised CLSI breakpoints for caspofungin cannot be safely adopted for Etest results. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen RH, Arendrup MC. Candida palmioleophila: characterization of a previously overlooked pathogen and its unique susceptibility profile in comparison with five related species. J Clin Microbiol. 2011 Feb;49(2):549–56. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02071-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arendrup MC, Perlin DS, Jensen RH, et al. Differential In vivo activity of Anidulafungin, Caspofungin and Micafungin against C. glabrata with and without FKS resistance mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Feb 21; doi: 10.1128/AAC.06369-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **28.Castanheira M, Woosley LN, Messer SA, et al. Frequency of fks mutations among Candida glabrata isolates from a 10-year global collection of bloodstream infection isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(1):577–80. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01674-13. Comprehensive collection of C. glabrata isolates with elevated echinocandin MICs are examined for fks mutations and individual susceptibility to the three echinocandins by the CLSI method. The revised breakpoints are evaluated and the differential MIC elevation associated with the specific mutations in this organism discussed. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. Anidulafungin and micafungin minimum inhibitory concentration breakpoints are superior to caspofungin for identifying FKS mutant Candida glabrata and echinocandin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 Sep 23;57:6361–5. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01451-13. First study showing that anidulafungin and micafungin can be used as markers for caspofungin susceptibility for CLSI testing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **30.Pham CD, Iqbal N, Bolden CB, et al. Role of FKS Mutations in Candida glabrata: MIC Values, Echinocandin Resistance, and Multidrug Resistance. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014 Aug 1;58(8):4690–6. doi: 10.1128/AAC.03255-14. Comprehensive study on echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata in four American cities. Increasing rates are found and detailed information of the FKS genotypes and individual susceptibility to each echinocandin provided. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ben-Ami R, Garcia-Effron G, Lewis RE, et al. Fitness and Virulence Costs of Candida albicans FKS1 Hot Spot Mutations Associated With Echinocandin Resistance. J Infect Dis. 2011 Aug;204(4):626–35. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh-Babak SD, Babak T, Diezmann S, et al. Global Analysis of the Evolution and Mechanism of Echinocandin Resistance in Candida glabrata. PLoS Pathog. 2012 May 17;8(5):e1002718. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee KK, MacCallum DM, Jacobsen MD, et al. Elevated Cell Wall Chitin in Candida albicans Confers Echinocandin Resistance In Vivo. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2012 Jan 1;56(1):208–17. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00683-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **34.Lackner M, Tscherner M, Schaller M, et al. Positions and Numbers of FKS Mutations in Candida albicans Selectively Influence In Vitro and In Vivo Susceptibilities to Echinocandin Treatment. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014 Jul 1;58(7):3626–35. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00123-14. First study demonstrating in vivo development of a heterogygeous double mutant of C. albicans with differential MIC elevation to the three echinocandins. Laboratory engineered mutants are generated and the role of the mutations confirmed in an animal model. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borghi E, Andreoni S, Cirasola D, et al. Antifungal resistance does not necessarily affect Candida glabrata fitness. Journal of Chemotherapy. 2013 Dec 6;26(1):32–6. doi: 10.1179/1973947813Y.0000000100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI document M27-A3. Clinical and laboratory Standards Institute; Pennsylvania, USA: 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; Approved standard - Third edition. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arendrup MC, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lass-Florl C, Hope W. EUCAST technical note on the EUCAST definitive document EDef 7.2: method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts EDef 7.2 (EUCAST-AFST) Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012 Jul;18(7):E246–E247. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **38.Arendrup MC, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lass-Flörl C, Hope WW. An Update from EUCAST focussing on Echinocandins against Candida spp. and Triazoles Against Aspergillus spp. Drug Resist Updat. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2014.01.001. In press. Comprehensive overview of the science and methodologies behind EUCAST clinical breakpoint development. Provide the reader with an understanding of the pitfalls related to susceptibility testing, the recent advances and how this may be translated to the routine laboratory using commercial tests. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marcos-Zambrano LJ, Escribano P, Sanchez C, et al. Antifungal Resistance to Fluconazole and Echinocandins Is Not Emerging in Yeast Isolates Causing Fungemia in a Spanish Tertiary Care Center. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014 Aug 1;58(8):4565–72. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02670-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40.Arendrup MC, Cuenca-Estrella M, Lass-Flörl C, Hope WW. EUCAST Technical Note on Candida and Micafungin, Anidulafungin and Fluconazole. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013 doi: 10.1111/myc.12170. In Press. provide the new micafungin and the revised anidulafungin and fluconazole breakpoints from EUCAST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) CLSI document M27-S4. Clinical and laboratory Standards Institute; Pennsylvania, USA: 2012. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts; Fourth informational Supplement. [Google Scholar]

- *42.Arendrup MC, Dzajic E, Jensen RH, et al. Epidemiological changes with potential implication for antifungal prescription recommendations for fungaemia: Data from a nationwide fungaemia surveillance programme. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19(8):E343–53. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12212. Recent data from the largest nation-wide (and thus population based) ongoing surveillance programme of fungal blood stream infections. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG, et al. The Presence of an FKS Mutation Rather than MIC Is an Independent Risk Factor for Failure of Echinocandin Therapy among Patients with Invasive Candidiasis Due to Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Sep;56(9):4862–9. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00027-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arendrup MC, Pfaller MA. Caspofungin Etest susceptibility testing of Candida species: risk of misclassification of susceptible isolates of C. glabrata and C. krusei when adopting the revised CLSI caspofungin breakpoints. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012 Jul;56(7):3965–8. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00355-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *45.Eschenauer GA, Nguyen MH, Shoham S, et al. Real-World Experience with Echinocandin MICs against Candida Species in a Multicenter Study of Hospitals That Routinely Perform Susceptibility Testing of Bloodstream Isolates. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2014 Apr 1;58(4):1897–906. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02163-13. Comprehensive multicentre study on the performance of Sensititre Yeast One for routine susceptibility testing of Candida and echinocandins. A nice interlaboratory agreement was documented, but the adoption of the revised CLSI nreakpoints for C. glabrata and C. krusei resulted in an unacceptably high number of mis classifications of susceptible isolates as intermediate or resistant. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arendrup MC, Rodriguez-Tudela JL, Park S, et al. Echinocandin susceptibility testing of Candida spp. using the EUCAST EDef 7.1 and CLSI M27-A3 standard procedures: Analysis of the influence of Bovine Serum Albumin Supplementation, Storage Time and Drug Lots. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011 Jan 18;55(4):1580–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01364-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *47.Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ, Jones RN, Castanheira M. Use of Anidulafungin as a Surrogate Marker to Predict Susceptibility and Resistance to Caspofungin among 4,290 Clinical Isolates of Candida using CLSI Methods and Interpretive Criteria. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014 Jun 20; doi: 10.1128/JCM.00782-14. Comprehensive evaluation of the performance of anidulafungin as marker for caspofungin resistance using the CLSI method. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *48.Pfaller MA, Messer SA, Diekema DJ, et al. Use of Micafungin as a Surrogate Marker To Predict Susceptibility and Resistance to Caspofungin among 3,764 Clinical Isolates of Candida by Use of CLSI Methods and Interpretive Criteria. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014 Jan 1;52(1):108–14. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02481-13. Comprehensive evaluation of the performance of micafungin as marker for caspofungin resistance using the CLSI method. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **49.Astvad KM, Perlin DS, Johansen HK, et al. Evaluation of Caspofungin Susceptibility Testing by the New Vitek 2 AST-YS06 Yeast Card Using a Unique Collection of FKS Wild-Type and Hot Spot Mutant Isolates, Including the Five Most Common Candida Species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013 Jan 1;57(1):177–82. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01382-12. One of the few available evaluations of a commercial susceptibility test for yeast that includes a comprehensive number of resistant strains, thereby allowing evaluation of detection of resistant mutants. A significant number of fks mutants were classified as susceptible. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **50.Dudiuk C, Gamarra S, Leonardeli F, et al. Set of Classical PCRs for Detection of Mutations in Candida glabrata FKS Genes Linked with Echinocandin Resistance. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014 Jul 1;52(7):2609–14. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01038-14. A low cost classical PCR that allows detection of echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata is described and validated against a set of characterised mutant isolates. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **51.Pham CD, Bolden CB, Kuykendall RJ, Lockhart SR. Development of a Luminex-Based Multiplex Assay for Detection of Mutations Conferring Resistance to Echinocandins in Candida glabrata. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2014 Mar 1;52(3):790–5. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03378-13. A less time consuming molecular approach for the tion of echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata is described and validated. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Carolis E, Vella A, Florio AR, et al. Use of Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry for Caspofungin Susceptibility Testing of Candida and Aspergillus Species. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2012 Jul 1;50(7):2479–83. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00224-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **53.Vella A, De Carolis E, Vaccaro L, et al. Rapid Antifungal Susceptibility Testing by Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization–Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry Analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2013 Sep 1;51(9):2964–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00903-13. First same-day susceptibility screening test for echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata using MALDI-TOF is described. The concept is attractive and deserves further development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reboli AC, Rotstein C, Pappas PG, et al. Anidulafungin versus fluconazole for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jun 14;356(24):2472–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **55.Vazquez J, Reboli A, Pappas P, et al. Evaluation of an early step-down strategy from intravenous anidulafungin to oral azole therapy for the treatment of candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: results from an open-label trial. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2014;14(1):97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-97. The only study published so far that addresses the necessary duration of echinocandin treatment before de-escalation to an oral azole. In patients fulfilling prespecified criteria (those not severely ill and responding to initial treatment) de-escalation was safe at day 5. The observations deserve further evaluation in a controlled trial. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nucci M, Queiroz-Telles F, Alvarado-Matute T, et al. Epidemiology of Candidemia in Latin America: A Laboratory-Based Survey. PLoS ONE. 2013 Mar 19;8(3):e59373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zimbeck AJ, Iqbal N, Ahlquist AM, et al. FKS mutations and elevated echinocandin MIC values among Candida glabrata isolates from U.S. population-based surveillance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010 Dec;54(12):5042–7. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00836-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pfaller MA, Moet GJ, Messer SA, et al. Geographic Variations in Species Distribution and Echinocandin and Azole Antifungal Resistance Rates among Candida Bloodstream Infection Isolates: Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008 to 2009) Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 2011 Jan 1;49(1):396–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01398-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tortorano AM, Prigitano A, Lazzarini C, et al. A 1-year prospective survey of candidemia in Italy and changing epidemiology over one decade. Infection. 2013;41(3):655–62. doi: 10.1007/s15010-013-0455-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]