Abstract

Summary: Non-targeted metabolomics technologies often yield data in which abundance for any given metabolite is observed and quantified for some samples and reported as missing for other samples. Apparent missingness can be due to true absence of the metabolite in the sample or presence at a level below detectability. Mixture-model analysis can formally account for metabolite ‘missingness’ due to absence or undetectability, but software for this type of analysis in the high-throughput setting is limited. The R package metabomxtr has been developed to facilitate mixture-model analysis of non-targeted metabolomics data in which only a portion of samples have quantifiable abundance for certain metabolites.

Availability and implementation: metabomxtr is available through Bioconductor. It is released under the GPL-2 license.

Contact: dscholtens@northwestern.edu

Supplementary information: Supplementary data are available at Bioinformatics online.

1 INTRODUCTION

High-throughput metabolomics profiling has surged in popularity with non-targeted technologies in particular offering opportunity for discovery of new metabolite associations with phenotypes or outcomes. A challenge to analyzing non-targeted output is the frequent occurrence of missing data (Hrydziuszko and Viant, 2012). These data are not ‘missing’ in the sense that they were not collected; rather, metabolites may be detected and their abundance quantified in some samples and not others. Typically conducted using nuclear magnetic resonance, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry or gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Issaq et al., 2009; Moco and Vervoort, 2007), non-targeted assays typically have unknown lower detection thresholds. Thus, when a given metabolite is not detected, it is unknown whether that metabolite was indeed absent or merely undetectable.

Several approaches for handling missingness have been described in metabolomics literature, including complete case analysis, imputation and adaptations of classic dimension reduction tools to allow for missing data. For metabolite-by-metabolite analyses, imputation is common, with methods including minimum, median and nearest neighbor imputation (Hrydziuszko and Viant, 2012). Partial least squares discriminant analysis and principal components analysis with missing data adaptations have been used, although these methods identify regression-based linear combinations of multiple correlated metabolites associated with a phenotype or outcome, and, in general, results are less translatable for understanding individual metabolite contributions (Andersson and Bro, 1998; Walczak and Massart, 2001).

An underused approach for metabolite-by-metabolite analysis is the Bernoulli/lognormal mixture model proposed by Moulton and Halsey (1995). This method simultaneously estimates parameters modeling the probability of non-missing response and the mean of observed values. Imputation is not required, and instead ‘missingness’ is explicitly modeled as either true absence or presence below detectability, consistent with non-targeted metabolomics technology. We used mixture models to analyze GC-MS metabolomics data (Scholtens et al., 2014), but, to our knowledge, there is no available software to easily perform these analyses that folds into existing high-throughput data analysis pipelines.

Noting the elegance of the mixture-model approach and the continued issue of missing data in metabolomics research, we present metabomxtr, an R package that automates mixture-model analysis. The core functions accept R objects typically handled in Bioconductor-type analyses or basic data frames, thus providing a flexible tool to complement existing user pipelines and preferences for data preprocessing.

2 MAIN FEATURES

2.1 Model specification

Models in metabomxtr are specified as follows. For a unique metabolite, y, with normally distributed values when present (generally following log transformation), the contribution of the ith observation to the likelihood is:

where pi represents the probability of metabolite detection in the ith sample, T is the threshold of detectability and δi is an indicator equal to 1 if the metabolite is detected and 0 otherwise. A logistic model is specified for pi, log(pi/(1 − pi))=xi’β, where xi and β are the covariate and parameter vectors, respectively. A linear model is specified for the mean of the observed response, µi, with µi= zi’α, where zi and α are the covariate and parameter vectors, respectively.

2.2 Function descriptions

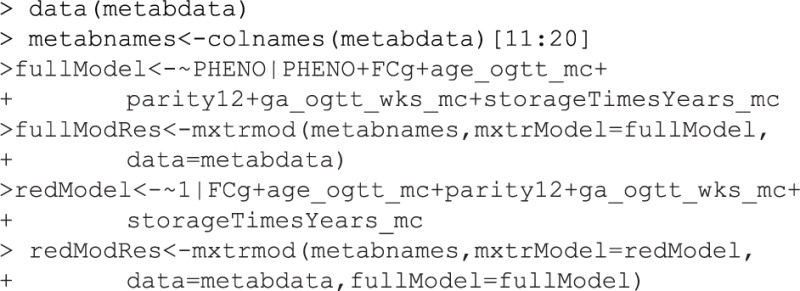

metabomxtr has two main functions: mxtrmod and mxtrmodLRT. mxtrmod executes mixture models, taking as inputs response variable names, a model formula and a data object (a matrix of values with NA to indicate missingness or an ExpressionSet R object). It returns optimized parameter estimates and the corresponding negative log likelihood value. Parameter vectors α and β are estimated using maximum likelihood using the optimx package. By default, T is set to the minimum observed metabolite abundance. Use of mxtrmod on the example dataset metabdata follows:

To evaluate the significance of specific covariates, mxtrmodLRT implements nested model likelihood ratio χ2 tests. Required arguments include mxtrmod output for full and reduced models and, if desired, method of multiple comparisons adjustment. mxtrmodLRT outputs a data frame of negative log likelihoods, χ2 statistics, degrees of freedom and P-values for each metabolite.

2.3 Comparison with imputation

To illustrate mixture models, we re-analyzed a subset of GC-MS data on 115 fasting serum samples from pregnant women involved in the population-based Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) Study, contained in the example data (Scholtens et al., 2014). A total of 49 non-targeted metabolites with at least five missing values were analyzed using mixture modeling as well as minimum imputation and five nearest neighbors. The predictor of interest was high (>90th percentile) versus low (<10th percentile) fasting plasma glucose (FPG). Samples for this pilot study were selected such that 67 had high FPG and 48 had low FPG. For minimum and nearest neighbor imputation, FPG groups were compared after imputation using linear models adjusted for study field center, parity, maternal and gestational age and sample storage time. The continuous portion of the mixture model also included these covariates, whereas the discrete portion included only FPG. FPG was removed for reduced models in mixture-model analysis. Nominal P < 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Of 49 metabolites analyzed, there was complete agreement (all significant or non-significant) among methods on 39 of them. Of the remaining 10 (Supplementary Fig. and Supplementary Table), mixture models detected significant effects for 7, nearest neighbor 4 and minimum 4. Of the seven mixture-model identifications, three were also detected by nearest neighbor, two also by minimum imputation and two were unique identifications. The mixture-model results were discussed from a biological perspective by Scholtens et al. (2014) and include leucine and pyruvic acid. One significant metabolite finding was unique to nearest neighbor imputation, but the result is questionable because the median of the imputed values exceeded the observed median, inconsistent with the notion of low abundance. For the two significant effects unique to minimum imputation, mixture-model P-values approached significance (0.018, 0.011), suggesting approximate agreement between the two methods.

3 DISCUSSION

The R package metabomxtr facilitates mixture-model analysis of non-targeted metabolomics data. Re-analysis of the HAPO pilot metabolomics data indicates that mixture-model analysis detects metabolites identified by other common imputation approaches and additionally identifies associations that would otherwise be missed. Rigorous testing of mixture models on a wider scale is warranted. In summary, metabomxtr provides metabolomics researchers a previously unavailable tool for handling non-targeted metabolomics missingness.

Funding: (R01-HD34242 and R01-HD34243) from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases, by the National Center for Research Resources (M01-RR00048, M01-RR00080) and by the American Diabetes Association and Friends of Prentice.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary Material

REFERENCES

- Andersson C, Bro R. Improving the speed of multi-way algorithms. Part I. Tucker 3. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. Syst. 1998;42:93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hrydziuszko O, Viant M. Missing values in mass spectrometry based metabolomics: an undervalued step in the data processing pipeline. Metabolomics. 2012;8:S161–S174. [Google Scholar]

- Issaq H, et al. Analytical and statistical approaches to metabolomics research. J. Sep. Sci. 2009;32:2183–2199. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200900152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moco S, Vervoort J. Metabolomics technologies and metabolite identification. Trends Analyt. Chem. 2007;26:855–866. [Google Scholar]

- Moulton L, Halsey N. A mixture model with detection limits for regression analyses of antibody response to vaccine. Biometrics. 1995;51:1570–1578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scholtens D, et al. Metabolomics reveals broad-scale metabolic perturbations in hyperglycemic mothers during pregnancy. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:158–166. doi: 10.2337/dc13-0989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak B, Massart D. Dealing with missing data part I. Chemometr. Intell. Lab. 2001;58:15–27. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.