The article by Alexander et al. (201X) titled “Sexuality Talk During Health Maintenance Visits” in this volume addresses physicians' discussion about sexuality with adolescents, and adolescents' responses based on audio-records of 253 adolescent visits with 49 physicians.1 The findings are consistent with other studies indicating low frequency and thoroughness of physician discussion with adolescents about sexuality in primary care.2,3

Will the Physician Bring Up the Topic?

In the Alexander et al. study, there was no adolescent talk about sexuality in any visit unless the physician first brought up the topic.1 Other studies also indicate that adolescents need the physician to initiate discussion to talk about sexuality.4 To improve adolescent sexual healthcare, physicians must more frequently initiate discussion about sexuality.

Unfortunately, physicians may be unable to initiate discussion about sexuality due to factors related to their lack of time and skill, as well as adolescent avoidance and other health priorities. Physicians may also be hesitant to discuss sexuality because of factors related to their comfort and confidence; concern about adolescents' or parents' comfort; beliefs about their role; judgments based on patient stereotyping; complexity of sexual issues; concern about legal and ethical issues; concern about adolescents' stage of cognitive development; and concern about the availability of follow-up services.5,6

Will the Adolescent Make any Disclosure about Sexuality to the Physician?

Another observation from the Alexander et al. article is that more adolescent talk about sexuality occurs with more physician talk about sexuality. In fact, physicians had to make on average 17.2 sexuality statements and spend on average 103.9 seconds talking about sexuality before the adolescent volunteered information and engaged in conversation about sexuality. Adolescent disclosure and engagement occurred in only 8% of visits.1 To increase adolescent discussion about sexual health, physicians must more thoroughly explore the topic through sustained communication.4

Adolescents may be hesitant to discuss sexuality with the physician because they do not: understand the purpose; want to be judged; feel confident in expressing themselves; trust their privacy; understand the importance; feel susceptible to sexual risks; feel comfortable talking about such issues; feel comfortable with the physician’s gender; feel enough of a relationship with the physician; and believe that the physician talk is directed to them rather than their parent.4

Most adolescents think their doctor is easy to talk to, are comfortable talking with their doctor, and think their doctor cares about them. However, many adolescents feel uncomfortable talking with their doctor about sexuality.4 Nevertheless, most adolescents value their physicians' opinions about sex; especially as they age and become less dependent on their parents' opinions.7 Those who have talked to their doctor about sexual issues tend to report comfort with such discussion.4

Are Physicians Ready to Hear Adolescents' Sexual Health Needs, and Commit to Addressing Adolescent Sexual Health?

Adolescents in the United States (US) experience higher rates of pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) than those in most other developed countries.8 Adolescent sexual behavior leading to STIs may include genital as well as oral and anal intercourse,9 be with persons of the same and/or other gender,10 and be with one person or multiple persons at one time.11 According to a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) survey of 9th-12th graders, significant numbers of sexually experienced adolescents report lack of condom use, lack of birth control, and lack of Depo-Provera at last sexual intercourse; having been forced to have sexual intercourse; having had first sexual intercourse before the age of 13 years; having had sexual intercourse with four or more persons; having used alcohol or drugs before last sexual intercourse; and having experienced dating violence. Rates of these experiences increase dramatically among those with same-sex sexual contact.10 This brief summary of adolescent sexual health highlights that sexual risks take many forms and many adolescents need sexual health information.

Unfortunately, different primary care guidelines project different levels of physician involvement in adolescent sexuality. Comprehensive involvement is projected by many recommendations based on the “best available evidence.”12 Other recommendations are strictly based on the most rigorous “outcomes-based research” and project a more limited, focused outcomes-based involvement.13 There is a lack of consensus and/or a lack of practice around an ideal adolescent sexual healthcare model for primary care.

Commitment to sexual topics

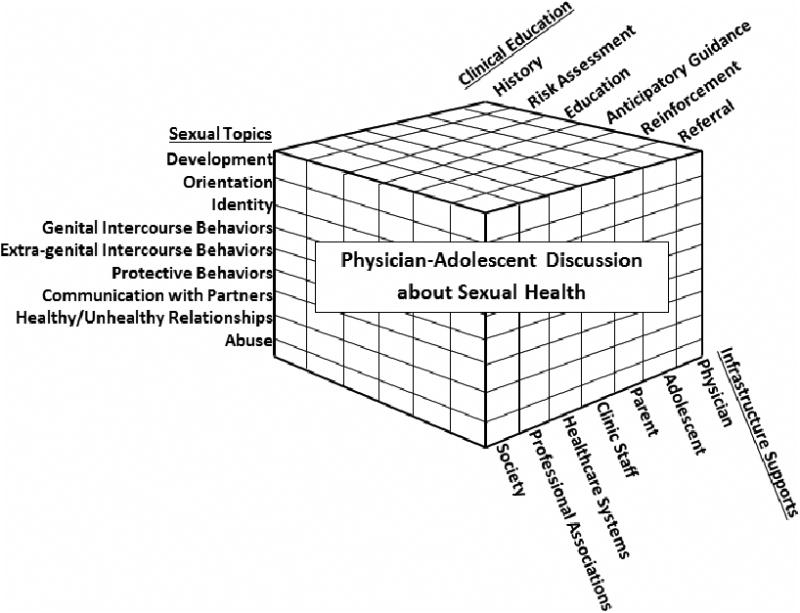

Comprehensive sexual health discussion with adolescents could include many sexual topics: Physical and emotional development; sexual orientation; gender identity; genital intercourse behaviors; extra-genital intercourse behaviors; STI and pregnancy protection behaviors; communication with partners; aspects of healthy and unhealthy relationships; and sexual abuse.12 Covering such a large array of important and sensitive topics may present challenges to physicians in busy primary care practices. Hence, recommendations regarding physician’s areas of focus when providing sexual healthcare require clarification.

Commitment to the steps of patient education

Adolescent sexual healthcare could involve a number of steps. Adolescents could be prepared for sexual discussion in their health visit.14 Physicians (or other staff) could assess the adolescent’s sexual history; conduct a risk assessment to identify adolescent physical, emotional, and behavioral issues requiring immediate or eventual follow-up; provide appropriate medical testing and treatment, as well as counseling and education; provide adolescents and parents guidance about what to expect and how to handle sexual changes; reinforce adolescents' healthy sexual choices; and make referrals for follow-up education and counseling regarding emotional and behavioral problems.12 Based on the many steps to sexual healthcare identified above, much time could be spent addressing them. The physician’s role and approach to the many steps of addressing adolescents' sexual health needs delineation.

Commitment to primary care infrastructure supports

Overcoming barriers to physician-adolescent discussion about sexual health may require multi-tiered infrastructure supports. Physicians may need sexual health education and skill building.15 Adolescents may need preparation for discussing sexuality in their primary care visit.4,14 Parents may need information and assistance to foster their adolescent’s regular relationship with a physician, and to be prepared for sexual health discussions.16 Physician clinic staff may need to be involved in various aspects of adolescent sexuality assessment and education.17 Healthcare systems may need to: Develop education programs and referral systems; provide more time for adolescent visits; reward physicians for meeting care recommendations; remove physician penalties for taking extra time with adolescents; develop policies that guide physician practice and protect physicians; and conduct patient panel epidemiology studies to help physicians be more focused on the sexual concerns their patients are most likely to experience.15 Professional Associations may need to better provide physicians with: Education opportunities, role delineation, practice recommendations, and advocacy to overcome structural barriers to physician sexuality discussion.12 Society may need to be better educated about the sexual medical needs of adolescents.18 Information systems may also play vital roles in helping adolescents, parents, and physicians better engage in sexual health education.

A New Vision Required

Concerning statistics on adolescents' sexual risks beg primary care commitment to discuss sexuality with adolescents. Provision of sexual health assessment and counseling in primary care can reduce adolescents' sexual risks and should be pursued.17,19 While parents, family members, teachers, coaches, faith leaders, and peers are important sources of sexual information; primary care physicians have access to objective, science-based sexual information that adolescents need. Unfortunately, as indicated by the Alexander et al. study, primary care physicians often do not discuss sexual health with adolescents. The article underscores that physician-adolescent discussion about sexuality is challenging, and begs re-examination of recommendations to physicians. A new primary care vision is needed to accommodate a range of sexual health topics, effective patient risk assessment and education practices, and multiple levels of primary care supports. The 2010 Affordable Care Act supports the patient-centered medical home concept for comprehensive and coordinated primary care which may provide an appropriate framework for a new adolescent sexual healthcare vision.12,20 Now may be the time to develop a new model of comprehensive adolescent sexual primary health care, and commit to physician-adolescent discussion about sexual health.

Figure. Components of a Multi-Tiered Commitment to Physician-Adolescent Discussion about Sexual Health Including Comprehensive: Clinical Education Practices, Coverage of Sexual Topics, and Infrastructure Support.

Acknowledgments

The following support enabled the preparation of this editorial: the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Prevention Research Centers Program Cooperative Agreement Number 3 U48 DP001929-0454 and the National Institute for Child Health and Human Development Grant Number R01 HD32572. The opinions and conclusions in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position of the agencies acknowledged above.

References

- 1.Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD, Pollak KI, et al. Sexuality talk during adolescent health maintenance visits. JAMA. XXXX;xx(xx):xx–xx. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donaldson AA, Lindberg LD, Ellen JM, Marcell AV. Receipt of sexual health information from parents, teachers, and healthcare providers by sexually experienced US adolescents. J Adoles Health. 2013;53(2):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein JD, Wilson KM. Delivering quality care: adolescents' discussion of health risks with their providers. J Adoles Health. 2002;30(3):190–195. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Cheng TL, Simmens SJ. Young adolescents' comfort with discussion about sexual problems with their physician. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(11):1146. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170360036005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boekeloo BO, Marx ES, Kral AH, Coughlin SC, Bowman M, Rabin DL. Frequency and thoroughness of STD/HIV risk assessment by physicians in a high-risk metropolitan area. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(12):1645–1648. doi: 10.2105/ajph.81.12.1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Summers D, Alpert I, Rousseau-Pierre T, et al. Mt Sinai J Med. 3. Vol. 73. New York: 2006. An exploration of the ethical, legal and developmental issues in the care of an adolescent patient; pp. 592–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Simmens SJ, Cheng TL. Tailoring STD/HIV prevention messages for young adolescents. Acad Med. 1996;71(10):S97–9. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199610000-00057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Darroch JE, Singh S, Frost JJ. Differences in teenage pregnancy rates among five developed countries: the roles of sexual activity and contraceptive use. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001:244–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haydon AA, Herring AH, Prinstein MJ, Halpern CT. Beyond age at first sex: Patterns of emerging sexual behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. J Adoles Health. 2012;50(5):456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health Risk Behaviors Among Students in Grades 9-12-- Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance, Selected Sites, United States 2001–2009. [Accessed September 8, 2013]; http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/pdf/ss/ss60e0606.pdf. [PubMed]

- 11.Rothman EF, Decker MR, Miller E, Reed E, Raj A, Silverman JG. Multi-person sex among a sample of adolescent female urban health clinic patients. J Urban Health. 2012;89(1):129–137. doi: 10.1007/s11524-011-9630-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan P, editors. American Academy of Pediatrics. Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. Third. 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solberg LI, Nordin JD, Bryant TL, Kristensen AH, Maloney SK. Clinical preventive services for adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(5):445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boekeloo BO, Schamus LA, Simmens SJ, Cheng TL, O'Connor K, D'Angelo LJ. A STD/HIV prevention trial among adolescents in managed care. Pediatr. 1999;103(1):107–115. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ozer EM, Adams SH, Lustig JL, et al. Increasing the screening and counseling of adolescents for risky health behaviors: a primary care intervention. Pediatr. 2005;115(4):960–968. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller K, Wyckoff S, Lin C, Whitaker D, Sukalac T, Fowler M. Pediatricians' role and practices regarding provision of guidance about sexual risk reduction to parents. J Prim Prev. 2008;29(3):279–291. doi: 10.1007/s10935-008-0137-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boekeloo BO, Griffin MA. Review of clinical trials testing the effectiveness of clinician intervention approaches to prevent sexually transmitted diseases in adolescent outpatients. Curr Pediatr Rev. 2005;1(2):173–185. doi: 10.2174/1573396054065457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beckett MK, Elliott MN, Martino S, et al. Timing of parent and child communication about sexuality relative to children' s sexual behaviors. Pediatr. 2010;125(1):34–42. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin JS, Whitlock E, O'Connor E, Bauer V. Behavioral counseling to prevent sexually transmitted infections: a systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(7):497–508. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-7-200810070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koh HK, Sebelius KG. Promoting prevention through the affordable care act. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(14):1296–1299. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1008560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]