Abstract

The current study examined the role of cognitive factors in the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms from pregnancy into the postpartum period. One hundred and one women were assessed for levels of rumination (brooding and reflection), negative inferential styles, and depressive symptoms in their third trimester of pregnancy and depressive symptom levels again at four and eight weeks postpartum. We found that, although none of the three cognitive variables predicted women’s initial depressive reactions following childbirth (from pregnancy to one month postpartum), brooding rumination and negative inferential styles predicted longer-term depressive symptom changes (from pregnancy to two months postpartum). However, the predictive validity of women’s negative inferential styles was limited to women already exhibiting relatively high depressive symptom levels during pregnancy, suggesting that it was more strongly related to the maintenance of depressive symptoms into the postpartum period rather than increases in depressive symptoms following childbirth. Modifying cognitive risk factors, therefore, may be an important focus of intervention for depression during pregnancy.

Researchers estimate that approximately 7% of women meet criteria for major depression in the first three months postpartum (O’Hara, 2009). Even more new mothers (up to 70 %) experience postpartum blues, a milder level of sadness and associated depressive symptoms, which often remits within the first 10 days postpartum (Whiffen, 1991; Gotlib, Whiffen, Mount, Milne, & Cordy, 1989). In fact, 45–65% of women report experiencing their first depressive episode within 1 year of giving birth (Moses-Kolko & Roth, 2004). Furthermore, infants, toddlers, and school-age children of mothers with postpartum depression are at risk for problems with emotion regulation, behavioral and psychological problems, insecure attachments, and delays in cognitive and language development (Beck, 1996; Murray & Cooper, 1997). This risk may be heightened with the mother’s subsequent depressive episodes (Philipps & O’Hara, 1991). Given that risk for future episodes increases with each depressive episode experienced (Solomon et al., 2000), these findings suggest that the childbearing years may present a unique opportunity for prevention and may be a time when vulnerable women and their families are likely to be at highest risk (Philipps & O’Hara, 1991).

A number of researchers have focused on risk factors for postpartum depression; however, this research has generally proceeded separately from the larger depression literature and has typically focused on factors related to the pregnancy itself (e.g. obstetric complications or hormone levels) or demographic factors (such as previous history of psychopathology, socioeconomic status, and parity), without grounding these investigations in existing theories of depression (cf. Whiffen & Gotlib, 1993). Although there is substantial individual variability, childbirth and taking care of a new born are stressful. Therefore, broader vulnerability-stress theories of depression may help to increase our understanding of which women may be at greatest risk for depression postpartum. Much of the research on depression risk more generally has focused on cognitive risk factors. Two of the primary cognitive theories of depression are the hopelessness theory and the response styles theory. In the hopelessness theory of depression (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, 1989), cognitive vulnerability to depression is defined as the tendency to attribute negative events to stable, global causes and to infer negative consequences and self-characteristics following the occurrence of negative events. An example of this type of negative inferential style would be the explaining the occurrence of a negative event in one’s life by saying “I’m worthless and can’t do anything right”. This type of explanation reflects an attribution of the cause of the event to stable (unlikely to change) and global (likely to affect many areas of one’s life) factors imply negative consequences (additional negative events in the future) and negative self-characteristics about the individual. With regard to the response styles theory (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1991), the tendency to respond to negative mood by ruminating (or repetitively thinking about why one is feeling sad or depressed and the consequences of depressive symptoms) is hypothesized to contribute to the development and maintenance of depression. Although early work testing the response styles theory focused on rumination generally, more recent research has focused on two distinct components of rumination, brooding and reflective pondering. Brooding is defined as “a passive comparison of one’s current situation with some unachieved standard” whereas reflection is defined as “a purposeful turning inward to engage in cognitive problem-solving to alleviate one’s depressive symptoms” (Treynor et al., 2003, p. 256). There is growing evidence that brooding and reflective rumination are distinct constructs and that brooding represents a more maladaptive form of rumination than reflection, with stronger links to depression (for a review, see Nolen-Hoeksema, Wisco, & Lyubomirsky, 2008).

Both the hopelessness theory and the response styles theory have garnered considerable support for predicting the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms and diagnoses in general community samples (for reviews, see Haeffel et al., 2008; Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). However, only one study of which we are aware has examined the link between rumination and postpartum depressive symptoms (O’Mahen, Flynn, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010). This study focused on women with elevated depressive symptom levels during pregnancy and found that levels of brooding rumination predicted residual change in depressive symptoms from pregnancy to three months postpartum among women with low but not high social functioning during pregnancy. In addition, no study of which we are aware has formally evaluated the hopelessness theory within the context of postpartum depression. This said, there is evidence that one of the three inferential styles featured in the hopelessness theory – negative attributional styles for the causes of negative events as defined in the hopelessness theory’s predecessor, the reformulated theory of learned helplessness (internal, stable, global attributions; Abramson, Seligman, & Teasdale, 1978) – and postpartum depressive symptoms (for a review, see O’Hara & Swain, 1996). In each of these studies, however, it is unclear whether cognitive risk factors predict increases in depressive symptoms following childbirth (development of symptoms) or whether they predict the maintenance of depressive symptoms from pregnancy into the postpartum period. Across studies, levels of depressive symptoms during pregnancy are one of the most salient predictors of postpartum depression (cf. O’Hara, Schlechte, Lewis, & Varner, 1991). In fact, forty to fifty percent of mothers who experience postpartum depression have significant symptoms of depression during their pregnancy (Whiffen, 1992; Yonkers et al., 2001).

Our goal in the current multi-wave prospective study, therefore, was to determine whether the vulnerabilities featured in the hopelessness theory of depression (negative inferential styles) and the response styles theory (brooding and reflection) could help to explain risk for postpartum depressive symptoms. In so doing, we specifically examined the development versus maintenance of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to postpartum. We also examined women’s functioning at two time points postpartum – 1 month and 2 months postpartum – to gain a better understanding of relatively short-term versus longer-term changes in depressive symptoms.

Method

Participants

Participants were 101 women in their third trimester of pregnancy. Women were only excluded if they were under the age of 18 or were unable to read and write in English. The average age of participants in this study was 28.44 years (SD = 6.39), and 89% were Caucasian. Participants were generally well educated (53.5% had a college degree or higher) and had a median yearly household income of $55,000 (range: < $5,000 to > $200,000 per year). Fifty-five percent of participants were pregnant with their first child and 73.5% were currently married.

Measures

Levels of rumination were assessed with the Ruminative Response Scale (RRS; Treynor et al., 2003). The RRS is a self-report questionnaire that asks participants to rate the frequency with which they think or do certain things when they feel sad, down, or depressed (e.g., “Go some place alone to think about your feelings”). The statements are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from almost always to almost never. Given concerns that some of the RRS items overlap with depressive symptoms, factor analytic studies have identified two subscales of the RRS – brooding and reflection – which are not confounded with depressive content (Treynor et al., 2003). The current study focused on these two subscales. Both 5-item subscales have demonstrated good psychometric properties in previous research; however, as noted above, the brooding subscale is more strongly related to depression and related constructs (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008). In the current study, the brooding and the reflection subscales exhibited adequate internal consistency (αs = .82 and.76, respectively).

Women’s negative attributional styles were assessed with the Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire (Peterson & Villanova, 1988).1 The EASQ is a self-report questionnaire that presents 12 hypothetical negative events. For each event, the individual is asked to write down what she believes would have been the cause of that event and then to rate that cause in terms of its internality, stability, and globality. The EASQ was modified for the current study in two ways. First, questions were added for each hypothetical event to assess the other two inferential styles featured in the hopelessness theory – negative inferential style for the consequences and self-worth implications of each event (i.e., ‘How likely is it that the [negative event] will lead to other negative things happening to you?’ and ‘To what degree does the [negative event] mean that you are flawed in some way?’). In addition, to reduce participant burden, only the first six hypothetical negative events from the EASQ were used in this study. Previous research has found that equivalent concurrent and predictive validity are obtained using these six items as with the full EASQ (Whitley, 1991). Consistent with other research testing the hopelessness theory (see Haeffel et al., 2008), we created a composite score by averaging participants’ inferences regarding causes (stability and globality ratings), consequences, and self-implication ratings for each of the hypothetical negative events. For this composite, higher scores indicate more negative inferential styles. The negative inferential style composite score exhibited good internal consistency in this study (α = .87).

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox, Holden, & Sagovsky, 1987) is a 10 item self-report questionnaire of depressive symptoms in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Individuals are asked to circle one of four responses for each item, which correspond to increasing symptom severity. Responses to items are summed to create a total score (maximum of 30), with higher numbers indicating more severe symptoms. The EPDS was designed to be a screening measure specifically for postpartum women and deemphasizes the somatic symptoms of depression, which are often experienced due to the pregnancy and birth alone. A cutoff score of 12 or higher exhibits good sensitivity (86%) and specificity (78%) in detecting depressive diagnoses in postpartum women (Cox et al., 1987). The EPDS has been validated for use in both prenatal and postnatal women. The EPDS has been shown to be reliable and valid across a number of studies (Evins & Theofrastous, 1997), displays good sensitivity and specificity (Eberhard-Gran, Eskild, Tambs, Opjordsmoen, & Samuelsen, 2001; Evins & Theofrastous, 1997), is sensitive to changes over time (Cox et al., 1987) and is acceptable to administer over the phone (Zelkowitz, & Milet, 1995). The EPDS demonstrated good internal consistency (αs = .85, .81, and.83 at T1–T3, respectively).

Procedure

Pregnant women in their third trimester were recruited for this study via advertisements in the local newspaper, flyers at local obstetrician’s offices, and information posted on online parenting groups for new mothers. After giving informed consent, participants completed the Time 1 study questionnaires (M = 49 days [SD = 28] before the baby’s birth). Participants then completed measures of depressive symptoms over the phone approximately 1 month (M = 35 days [SD = 13]) and 2 months (M = 65 days [SD = 13]) postpartum. Mothers were compensated $25 for their participation.

Results

Of the 101 women who completed the initial assessment, 91 completed the Time 2 assessment and 93 completed the Time 3 assessment. Given the presence of missing data, we examined whether the data were missing at random, thereby justifying the use of data imputation methods for estimating missing values (cf. Shafer & Graham, 2002). Little’s missing completely at random (MCAR) test, for which the null hypothesis is that the data are MCAR (Little & Rubin, 1987) was nonsignificant, χ2(67) = 65.74, p = .52. Given this, Multiple Imputation was used to generate 20 imputed dataset, which were used in all subsequent analyses. Following the standard approach, the results presented reflect the pooled estimates across these data sets. This approach yields more reliable parameter estimates than other methods of dealing with missing data, including single imputation methods (see Shafer & Graham, 2002). Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables are presented in Table 1. We should also note that although the mean level of depressive symptom decreased across the follow-up, women reported a wide range of symptoms on the EPDS at all three assessment points (0–22 at Time 1; 0–20 at Time 2 and 3). Also, 21% of women scored above the suggested cutoff of 12 (Cox et al., 1987) at Time 1, 7% scored above this cutoff at Time 2, and 5% scored above the cutoff at Time 3. Therefore, although drawn from the community, there was a meaningful range of depressive symptoms displayed in our sample.

Table 1.

Correlations and Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | T1 EPDS | - | |||||||||||

| 2. | T2 EPDS | .41 | - | ||||||||||

| 3. | T3 EPDS | .48 | .56 | - | |||||||||

| 4. | EASQ | .35 | .24 | .23 | - | ||||||||

| 5. | RRS-Brooding | .61 | .26 | .48 | .42 | - | |||||||

| 6. | RRS-Reflection | .54 | .23 | .35 | .22 | .54 | - | ||||||

| 7. | Age | −.25 | −.24 | −.31 | −.17 | −.13 | −.15 | - | |||||

| 8. | Caucasian | −.08 | −.06 | −.09 | −.02 | −.04 | −.15 | .17 | - | ||||

| 9. | Income | −.49 | −.06 | −.40 | −.13 | −.35 | −.33 | .40 | .21 | - | |||

| 10. | Marital Status | −.50 | −.23 | −.42 | −.09 | −.31 | −.34 | .40 | .11 | .48 | - | ||

| 11. | Children (#) | .01 | −.30 | −.17 | −.02 | −.04 | −.04 | .42 | .08 | −.03 | .05 | - | |

| 12. | Miscarriage | .19 | −.01 | .07 | .00 | .15 | .03 | .06 | .02 | −.04 | −.11 | .05 | - |

| Mean | 8.07 | 5.96 | 4.53 | 3.33 | 9.56 | 8.85 | 28.81 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| SD | 4.76 | 4.11 | 4.12 | 0.88 | 3.44 | 3.17 | 2.20 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Median | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | $55K | - | 0 | - | |

| % | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 90% | - | 74% | - | 23% |

Note. EPDS = Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Inventory; EASQ = Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire; RRS-Brooding = Ruminative Response Scale - Brooding subscale; RRS-Reflection = Ruminative Response Scale - Reflection Subscale. Caucasian was coded so that 1 = Caucasians and 0 = other racial/ethnic groups. Marital status was coded so that 1 = married 0 = unmarried. Children = number of children for each mother prior to the index pregnancy. Miscarriage was coded so that 1 = prior miscarriage and 0 = no history of miscarriage.

Correlations ≥ |.22| significant at p < .05. Correlations ≥ |.26| significant at p < .01. Correlations ≥ |.31| significant at p < .001.

Next, hierarchical regression analyses were used to examine short term changes in women’s depressive symptoms from the third trimester to one month postpartum (T1 to T2). For these analyses, T2 EPDS scores served as the criterion variable and T1 EPDS scores were entered as a covariate in block 1 of the regression, allowing us to examine residual change in depressive symptoms from T1 to T2. As noted above, we also included women’s marital status and number of children as covariates in these analyses. The cognitive risk factors were examined in separate regressions by adding them in block 2 of the regressions. Consistent with the recommendations of Joiner (1994), we also examined interactions between the cognitive variables and T1 EPDS scores to determine whether the cognitive variables predicted the development versus maintenance of depressive symptoms into the postpartum period. None of these analyses were significant, indicating that none of the cognitive risk factors predicted women’s short-term depressive reactions during the postpartum period (lowest p = .30).

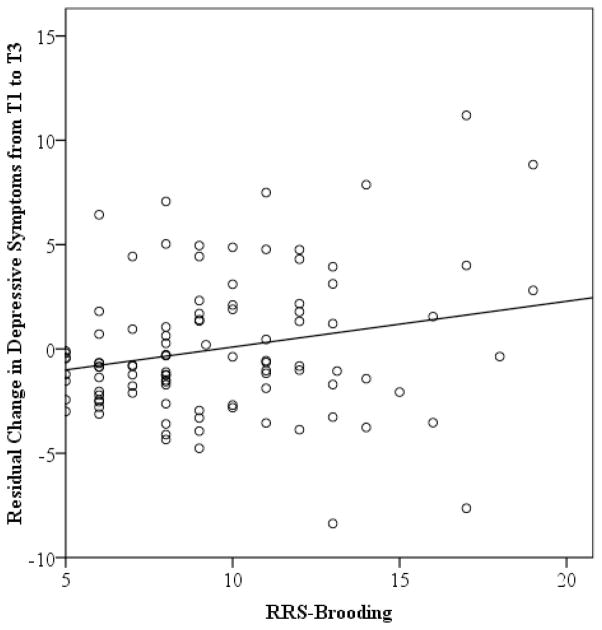

In contrast, the cognitive risk factors did predict longer-term depressive symptom changes. Specifically, levels of brooding rumination assessed during the third trimester predicted residual change in depressive symptom between the third trimester and two months postpartum (T1 to T3), t(98) = 2.81, p = .005, pr = .28. The interaction between brooding rumination and initial depressive symptom levels was not significant, t(97) = 1.02, p = .31, pr = .12, suggesting that the predictive validity of brooding rumination was similar for women exhibiting higher and lower depressive symptom levels at the initial assessment. The results of this analysis are plotted in Figure 1, which shows the relation between baseline levels of brooding rumination and residual change in depressive symptoms from T1 to T3. As can be seen in the figure, although levels of depressive symptoms decreased over the follow-up for the majority of women, those with high levels of brooding rumination experienced an increase in depression during the postpartum period.

Figure 1.

Prediction of residual change in depressive symptoms from the T1 (3rd trimester) to T3 (2 months postpartum) assessment. RRS-Brooding = Ruminative Response Scale-Brooding subscale.

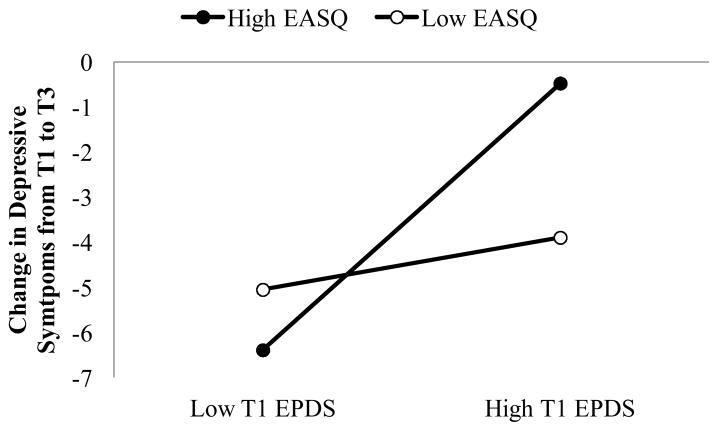

We also found a significant EASQ × T1 EPDS interaction predicting T3 depressive symptoms, t(97) = 3.35, p = .001, pr = .34. Examining the form of this interaction (cf. Aiken & West, 1991), we found that women’s inferential styles predicted residual change in depressive symptoms among those exhibiting relatively high (+1 SD), t(97) = 2.98, p = .003, pr = .31, but not low (−1 SD), t(97) = −1.40, p = .16, pr = −.15, depressive symptoms at the initial assessment. As can be seen in Figure 2, although the majority of women experienced decreases in depressive symptom across the follow-up, those with negative inferential styles and relatively high levels of depressive symptoms during their third trimester of pregnancy maintained their levels of depressive symptoms across the follow-up (average EPDS in this group at T3 = 7.60). In contrast, levels of reflective rumination did not predict residual change in depressive symptoms from T1 to T3, either as a main effect, t(98) = 1.18, p = .24, pr = .12, or interacting with T1 depressive symptom levels, t(97) = 0.43, p = .67, pr = .05.

Figure 2.

Summary of inferential styles × T1 depressive symptoms predicting change in depressive symptoms from the T1 (3rd trimester) to T3 (2 months postpartum) assessment. EASQ = Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire. EPDS = Edinburgh Depression Rating Scale.

Finally, given the strong links observed in previous studies between demographic characteristics and risk for (postpartum) depression, we conducted additional analyses to determine whether the results reported above would be maintained even after statistically controlling for the influence of demographic variables. Even after statistically controlling for the potential influence of women’s age, race, marital status, family income, number of other children in the home, and history of miscarriage, Time 1 levels of brooding rumination continued to significantly predict residual change in women’s depressive symptoms from the third trimester of pregnancy to 4 months postpartum, t(92) = 2.75, p = .006, pr = .28. Similarly, controlling for each of these demographic variables, women’s inferential styles continued to predict changes in depressive symptoms among those with relatively high depressive symptom levels at the initial assessment, t(91) = 2.73, p = .006, pr = .29.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine the ability of two leading cognitive theories of depression – hopelessness theory and response styles theory – to explain postpartum depression risk. Adding to the growing body of depression research suggesting the important role of brooding rumination (Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008; O’Mahen et al., 2010), we found that levels of brooding rumination predicted residual change in women’s depressive symptoms from the third trimester of pregnancy to two months postpartum, even after statistically controlling for the influence of demographic variables. Also, adding to the existing literature suggesting that brooding rumination is a more maladaptive form of rumination than reflection (see Nolen-Hoeksema et al., 2008), the effects were specific to brooding. Although reflective rumination was significantly related to depressive symptoms concurrently during pregnancy, it did not predict prospective changes in these symptoms. We also found some support for the hopelessness theory. Specifically, women’s negative inferential styles also predicted depressive symptom levels at two months postpartum. However, this finding was limited to women who already had elevated depressive symptom levels during their third trimester, suggesting that inferential styles predicted the maintenance of symptoms present during the third trimester rather than the development of new symptoms postpartum.

In contrast to these results, none of the cognitive variables predicted residual change in depressive symptoms from pregnancy to one month postpartum. The reason for this difference in finding is unclear and certainly warrants additional investigation. One possibility is that shorter-term depressive reactions are more strongly influenced by contextual factors (e.g., health of baby, availability of social support, etc.) and that the predictive power of cognitive risk factors emerges only after initial period of adjustment. Again, future research is need to more clearly understand influences on shorter- versus longer-term depressive reactions following child birth.

Another finding from this study that warrants discussion is that women exhibited the highest levels of depressive symptoms during pregnancy (with 21% of women scoring above the suggested cutoff of 12 on the EPDS). For the sample as a whole, these symptoms reduced across the follow-up. However, there was significant variability in this pattern, with approximately 5% of women still scoring above the cutoff on the EPDS at two months postpartum, which is consistent with rates of postpartum depression observed in previous research (for a review, see O’Hara, 2009). The current results suggest that cognitive models of depression may help to account for which women will maintain their depression following pregnancy (inferential styles) as well as those at risk for experiencing depressive symptom increases postpartum (brooding rumination). Cognitive models, therefore, may provide an important area of intervention, as many other known risk factors (such as demographic factors) are often difficult to modify during pregnancy.

The current results also raise an interesting and important question. When is the best time to assess risk and intervene to reduce depression in pregnant women? To the extent that depressive symptoms are already elevated by the third trimester, this suggests the utility of earlier screening for depression and depression risk. Indeed, a limitation of this study is that we did not conduct our initial assessment until the third trimester of women’s pregnancies. Future research is needed to examine risk preconception and then throughout pregnancy to determine at which point identification of those most at risk can be maximized. For example, can levels brooding rumination and/or negative inferential styles be used to predict which women are at greatest risk for developing depression during pregnancy, which then may either be maintained or exacerbated during the postpartum period?

The current study exhibited a number of strengths, including the focus on determining whether leading models of cognitive vulnerability to depression can be applied to the prediction of postpartum depression risk, the multi-wave prospective design, and the specific examination of depressive symptom increases following childbirth versus maintenance of depressive symptoms from pregnancy to postpartum. The study also had several limitations that highlight important areas for future research. First, all of the assessments relied upon women’s self-reports, which could have been subject to recall or response bias. Also, the mono-method assessment could have inflated relations among the study variables. Future studies testing cognitive models of depression risk, therefore, would benefit from the inclusion of interviewer-administered measures of depressive symptoms. Second, although this study focused on leading theories of cognitive vulnerability to depression, we recognize that there are multiple levels of influence in women’s depression risk during pregnancy and postpartum, which we did not assess for in this study. Third, building from cognitive vulnerability-stress models of depression risk, we conceptualized childbirth as a common stressor shared by all the women in our sample. However, the stress associated with labor/delivery and with taking care of a newborn obviously varies considerably across families. Therefore, to provide a more powerful test of the cognitive models, future research should include a more detailed assessment of the contextual stress experienced by each woman so that these idiographic differences can be captured.

In summary, the current results provide strong support for the role of cognitive risk factors in postpartum depressive symptoms. They also suggest that inferential styles and brooding rumination may play different roles in women’s depression risk (maintenance and development of depressive symptoms, respectively). Importantly, however, the current results suggest that many women are already experiencing clinically significant levels of depressive symptoms by their third trimester. Future research, therefore, should focus earlier in pregnancy to determine the most effective window during which to identify at-risk women before they develop depression.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grants HD048664 and HD057066 awarded to B.E. Gibb.

Footnotes

Although negative inferential styles in adults are most commonly assessed with the Cognitive Style Questionnaire (Haeffel et al., 2008), five of the 12 hypothetical negative events on this scale focus on school work/academic performance, which may be less relevant for a general community sample of expectant mothers. Therefore, we chose to use the EASQ instead because it focuses more broadly on negative events that may be more typical for a community sample.

References

- Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. 1989;96:358–372. [Google Scholar]

- Abramson LY, Seligman MEP, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1978;87:49–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. A Meta-analysis of the relationship between postpartum depression and infant temperament. Nursing Research. 1996;45:225–230. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199607000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberhard-Gran M, Eskild A, Tambs K, Opjordsmoen S, Samuelsen SO. Review of validation studies of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2001;104:243–249. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evins GG, Theofrastous JP. Postpartum depression: A review of postpartum screening. Primary Care Update. 1997;4:241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Whiffen VE, Mount JH, Milne K, Cordy NI. Prevalence rates and demographic characteristics associated with depression in pregnancy and the postpartum. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1989;587:269–274. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.57.2.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeffel GJ, Gibb BE, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Hankin BL, Joiner TE, Jr, Swendsen JD. Measuring cognitive vulnerability to depression: Development and validation of the Cognitive Style Questionnaire. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28:824–836. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE., Jr Covariance of baseline symptom scores in prediction of future symptom scores: A methodological note. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 1994;18:497–504. [Google Scholar]

- Little R, Rubin D. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: Wiley; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Moses-Kolko EL, Roth EK. Antepartum and postpartum depression: Healthy mom, healthy baby. Journal of the American Medical Women’s Association. 2004;59:181–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray L, Cooper PJ. Postpartum depression and child development. Guilford Press; New York: 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking rumination. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW. Postpartum depression: What we know. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009;65:1258–1269. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, Varner MW. Controlled prospective study of postpartum mood disorders: Psychological, environmental, and hormonal variables. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:63–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara MW, Swain AM. Rates and risk of postpartum depression – a meta-analysis. International Review of Psychiatry. 1996;8:37–55. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahen HA, Flynn HA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination and interpersonal functioning in perinatal depression. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29:646–667. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C, Villanova P. An expanded attributional style questionnaire. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97:87–89. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philipps L, O’Hara MW. Prospective study of postpartum depression: 4 ½ –year follow-up of women and children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:151–155. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soloman DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller T, Lavori PW, Shea MT, Coryell W, Warshaw M, Turvey C, Maser JD, Endicott J. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;157:229–233. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: A psychometric analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2003;27:247–259. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE. The comparison of postpartum with nom-postpartum depression: A rose by any other name. Journal of Psychiatric Neuroscience. 1991;16:160–165. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE. Is postpartum depression a distinct diagnosis? Clinical Psychology Review. 1992;12:485–508. [Google Scholar]

- Whiffen VE, Gotlib IH. Comparison of postpartum and nonpostpartum depression: Clinical presentation, psychiatric history, and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1993;61:485–494. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.61.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitley BE. A short form of the Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1991;56:365–369. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa5602_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonkers KA, Ramin SM, Rush AJ, Navarrette CA, Carmody T, March D, Hartwell S, Leveno KJ. Onset and persistence of postpartum depression in an inner-city maternal health clinic system. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:1856–1863. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.11.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelkowitz P, Milet TH. Screening for postpartum depression in a community sample. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;40:80–86. doi: 10.1177/070674379504000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]