Abstract

The current study examined whether the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol-related outcomes was mediated by college adjustment. Participants (N=253) completed an online survey that assessed drinking motives, degree of both positive and negative college adjustment, typical weekly drinking, and past month negative alcohol-related consequences. Structural equation modeling examined negative alcohol consequences as a function of college adjustment, drinking motives, and weekly drinking behavior in college students. Negative college adjustment mediated the relationship between coping drinking motives and drinking consequences. Positive college adjustment was not related to alcohol consumption or consequences. Positive reinforcement drinking motives (i.e. social and enhancement) not only directly predicted consequences, but were partially mediated by weekly drinking and degree of negative college adjustment. Gender specific models revealed that males exhibited more variability in drinking and their positive reinforcement drinking motives were more strongly associated with weekly drinking. Uniquely for females, coping motives were directly and indirectly (via negative adjustment) related to consequences. These findings suggest that interventions which seek to decrease alcohol-related risk may wish to incorporate discussions about strategies for decreasing stress and increasing other factors associated with better college adjustment.

Keywords: Alcohol, College Adjustment, Consequences, Drinking Motives, Drinking, Gender Differences

1. Introduction

For many college students, the transition into college is accompanied by the introduction to a culture in which alcohol use plays a conspicuous role. An estimated 80% of students drink alcohol (NIAAA, 2002) and 40–50% engage in heavy episodic (HED) or binge drinking (four or more drinks in a row for women or five or more drinks in a row for men; O'Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). Nearly one-quarter of students report engaging in frequent HED (three or more HED events in the previous two weeks; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008; Wechsler et al., 2002). Heavy drinking among college students is associated with a range of serious primary (e.g., psychological impairment, memory loss, risky sexual behavior, and addiction) and secondary consequences (e.g., academic impairment, sexual victimization, car accidents, violence, and death; Hingson et al., 2009; Hingson et al., 2002; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008; Wechsler et al., 2002).

1.1. Drinking motives

One's motives for drinking are an identified pathway to alcohol use (Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988; Kuntsche et al., 2006), and are reflective of both personal and environmental influences on alcohol use (Cox & Klinger, 1988; 1990). Thus, drinking motives are both a practical and meaningful avenue to better understand and intervene with alcohol use and its potentially harmful effects in college populations. Generally speaking, individuals drink primarily to create or enhance positive outcomes or avoid negative outcomes (Cox & Klinger, 1988, 1990). Cooper et al. (1992) investigated specific drinking motives individuals endorse and determined that they centered around three main areas: enhancement (e.g., drinking to induce positive mood), social (e.g., drinking to be more outgoing), and coping (e.g., drinking to avoid negative emotions). Conceptually, social motives, and to a large extent enhancement motives, are considered to be positive reinforcement motives for drinking and are only indirectly associated with consequences through increased alcohol use (Cooper, 1994; Kuntsche et al., 2005. Coping drinking motives are considered negative motives, as drinkers attempt to use alcohol to take away or deal with some kind of negative state. They are commonly associated with negative alcohol-related problems, over and above the quantity of alcohol consumed (Kassel et al., 2000; Kuntsche et al., 2007b, 2006; Simons et al., 2000).

1.2. Drinking motives’ relationship to consequences

Studies sampling general college student populations have consistently documented that college students most frequently endorse social and enhancement motives, which in turn are frequently associated with higher consumption levels (Kuntsche, Knibbe, Gmel, & Engels, 2005; LaBrie et al., 2007; Lewis et al., 2007). While coping motives are less frequently endorsed, they are consistently and more strongly related to negative alcohol-related consequences. However, the nature of this relationship is not fully understood. For example, two studies found coping drinking motives to exhibit a direct link to alcohol-related consequences (Kassel, Jackson, & Unrod, 2000: Martens, Neighbors, et al., 2008), while another study demonstrated the relationship between coping and alcohol-related consequences was mediated by level of alcohol use (Ham et al., 2009). Finally, other studies found coping motives to be both directly and indirectly associated with drinking consequences (Carey & Correia, 1997; Kuntsche et al., 2007a; Merrill & Read, 2010). While research may agree that coping motives are related to alcohol consequences, the full nature of this relationship requires further understanding.

1.3. Drinking motives’ relationship to drinking in college

Drinking motives are reliably and strongly linked to alcohol use in adolescents (Cooper, 1994; Cox & Klinger, 1988; Kuntsche et al., 2005). While drinking motives certainly continue to impact alcohol use in college populations (Kuntsche et al., 2005), the direct relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use appears to be less robust in college, with studies finding associations between motives and alcohol diminishing over time (Sher et al., 1996) or failing to find a direct link between motives and alcohol use (Read et al., 2003). The weakening direct relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use in college populations may suggest a more complicated relationship between drinking motives and drinking than the reliably direct linkage evidenced in adolescence. Indeed, recent research has found that drinking motives’ relationship to drinking is mediated by cognitive, emotional, and behavioral traits (i.e., the temptation or restraint to drink; Lyvers et al., 2010), as well as protective behavioral strategies an individual employs while drinking (LaBrie et al., 2011; Martens et al., 2007), confirming that drinking motives may in some cases, take on a more indirect role in their relationship to college student drinking.

As the transition to college is marked by significant personal and social changes, including dramatic changes in alcohol use behaviors (LaBrie, Hummer, & Pedersen, 2007; Labrie et al., 2008; Schulenberg et al., 2001), it is likely this transitional period exerts some measure of influence on the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use. Thus, the current study examines college adjustment, which is highly representative of an individual's progress through this life transition (Baker & Siryk, 1984), as a potential mediator between drinking motives and alcohol-related outcomes.

1.4. College adjustment

The college environment presents a dramatic lifestyle change for many students. Some students quickly acclimate to this environment while others struggle to adjust. Schulenberg et al. (2001) state that a student's time at college can be stressful and characterize it as a “developmental disturbance” in which the student is presented with a wide range of academic, social, and developmental challenges that must be navigated concomitantly with the sudden increase in autonomy. As a result of these challenges, students are experiencing record stress levels (Pryor et al., 2010). To help deal with this stress, students turn to a variety of both healthy and risky coping strategies (Bray et al., 1999). Coping with this stress can be problematic for students who lack healthier coping strategies (e.g., social support networks).

They may turn to drinking in order to cope (Cooper, 1994; Park & Levenson, 2002). In turn, coping-motivated alcohol use is positively related to psychological maladjustment in college students (Carver & Scheier, 1994). Without the ability to adequately cope with the stressors and challenges of the college environment, these students are at heightened risk for poorer college adjustment (Leong et al., 1997).

Students experiencing poorer college adjustment as a result of coping drinking motives, are likely at a heighted risk of experiencing alcohol-related consequences. Record numbers of students are struggling to adjust to college, feeling overwhelmed by the demands of college life and reporting record-low ratings on physical and emotional well-being (Dyson & Renk, 2006; Weinstein & Laverghetta, 2009). This is particularly concerning for students lacking healthy coping mechanisms and using alcohol as an ineffective coping mechanism to alleviate stress, as research suggests that drinking consequences are based more on psychological characteristics such as negative affect than alcohol consumption levels alone (Bonin et al., 2000; Park, 2004; Park & Grant, 2005).

Further, the typical conception of college adjustment research, which sees adjustment on a single-scale continuum ranging from poorly adjusted to highly adjusted (Baker & Siryk, 1984), may not fully account for actual student experiences. For example, a student may simultaneously have both significant positive and negative college adjustment experiences. However, this does not place him or her in the middle of a single continuum; it instead indicates a more complex level of adjustment. As such, it may be more accurate to measure both positive and negative college adjustment separately to capture adjustment ambivalence. Positive adjustment is characterized by experiencing events or engaging in behaviors that are indicative of healthy and normal adjustment to college such as frequent interaction with professors or making new friends (Baker & Siryk, 1999). Negative adjustment to college is characterized by experiencing events or engaging in behaviors that signify poorer adjustment to college such as academic trouble or social anxiety (Baker & Siryk, 1999).

1.5. Study aims and hypotheses

Studies of college students primarily hypothesize a direct relationship from coping drinking motives to alcohol use and/or alcohol consequences, but research shows that these hypotheses are not always supported. Moreover, research has found the correlation between drinking quantity and frequency and alcohol-related negative consequences in college populations to rarely exceed the moderate range of 0.6 (LaBrie et al., 2010; Larimer et al., 2001; Lee et al., 2010). Given that neither drinking behaviors nor motives fully account for the variance in consequences, suggests a need to explore other potentially influential and intervening factors.

This study introduced both degree of positive adjustment (i.e., experiencing positive aspects of college adjustment, such as satisfaction with social group) and degree of negative adjustment (i.e., experiencing negative aspects of college adjustment, such as struggles with academic workload) as potential factors mediating the relationship between motives and drinking outcomes. We hypothesized that coping motives will negatively impact a student's adjustment to college. We further hypothesized that poorer adjustment will place a student at heightened risk for experiencing negative alcohol-related consequences. Specifically we hypothesized that students who report coping drinking motives will also report a high degree of negative college adjustment that will be directly related to negative alcohol-related consequences. Further, students who report drinking for positive reinforcement drinking motives (i.e. social and enhancement) will report a high degree of positive college adjustment. However, we did not expect a high degree of positive adjustment to be related to alcohol-related outcomes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Over two sequential semesters (fall and spring), 253 students from a private, mid-size, west-coast university seeking class credit in the psychology subject pool completed an online assessment. Students (N=253) reported a mean age of 19.01 years (SD=1.65) and the sample was 59.7% female. Additionally, 59.3% were first years, 30.2% sophomores, 8.9% juniors, and 1.6% seniors. The ethnic composition was varied: 60.5% Caucasian/White, 14.7% Hispanic/Latino/a, 8.9% Mixed, 6.9% Asian, 4.7% African American/Black, 2.3% Other, 1.6% Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 0.4% Native American/Alaska Native,

2.2. Design and procedure

All measures, forms, and procedures were approved by a local Institutional Review Board. Inclusion criteria for the current study were that the student had access to a computer and that he/she would complete a 30 minute online survey. If the student signed up for the current study, research staff sent an email to the student with a study description and a link to an informed consent form documenting the confidentiality of responses. Upon submitting their consent, students were taken to the online surveys.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Student alcohol consumption

The Daily Drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins et al., 1985; Dimeff et al., 1999) was used to generate the quantity of drinks consumed and the frequency of consumption during a typical week. Participants reported on the typical number of drinks they consumed on each day of the week. Typical weekly drinking was calculated by summing participants’ responses for each day of the week. The DDQ has been used in numerous studies of college student drinking and has demonstrated good convergent validity and test–retest reliability (Marlatt et al., 1998; Neighbors et al., 2006).

2.3.2. Alcohol-related consequences

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) assessed the occurrence of 23 negative consequences resulting from one's drinking over the past month (e.g., “Not able to do your homework or study for a test” and “Passed out or fainted suddenly”). Each item is rated on a scale from 0 to 4 with 0 indicating “never” and 4 indicating “more than 10 times”. The RAPI demonstrated good reliability (α=.91).

2.3.3. College adjustment

Adjustment to college was measured using 55 items from the 67-item Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (Baker & Siryk, 1989; 1999). Twelve items referring to commuter students were not relevant to the current student population in which 82.7% of students live on campus, and were subsequently not included in the questionnaire. The SACQ assesses overall adjustment to college by incorporating four specific areas (academic, personal, social, and institutional adjustment). Response options for all items used a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Doesn't apply to me at all) to 9 (Applies very closely to me). Inter-item reliability for the measure for all 55 items was acceptable (α=.83). The SACQ has been used in many studies and has generally shown good reliability and external validity (e.g., Baker & Siryk, 1984, 1986, 1999; Conti, 2000; Hertel, 2002). However, a recent critique of the scale has raised concern with the reliability of the original four subscales of the SACQ (Taylor & Pastor, 2007). In response to this critique and in an effort to further explore our hypotheses, we conducted an exploratory analysis of SACQ and determined a two-factor scale, which we called positive college adjustment experiences (e.g., satisfaction with college, good health, social confidence) and negative college adjustment experiences (e.g., academic problems, thoughts of dropping out, lack of motivation). The final two-factor scale contained 25 items measuring positive adjustment experiences (α=.93) and 30 items measuring negative college adjustment experiences (α=.92; see Appendix Table A.1). Based on criticisms set forth by Taylor and Pastor (2007) along with the theoretical considerations formed from previous research and the excellent Cronbach's alphas for the two-factor scale, the decision was made to use the two-factor college adjustment scale for the present analyses.

2.3.4. Drinking motives

The four subscales of the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ; Cooper, 1994), coping, conformity, social, and enhancement subscales, were used to assess students’ motivations for drinking. A mean composite was created for the coping subscale. The social and enhancement subscales were combined to create a mean composite labeled “positive motives.” The authors of the scale commonly consider social and enhancement motives to both be measures of positive reinforcement drinking motives whereas coping is distinctly negative (Cooper, 1994). Conformity motives were excluded as college students do not commonly endorse conformity motives (Kuntsche & Cooper, 2010) and conformity motives in college populations are not strongly related to our variables of interest (i.e., alcohol consumption and alcohol consequences; Ham, Zamboanga, Bacon, & Garcia, 2009; Kuntsche & Cooper, 2010; Martens, Rocha, Martin & Serrao, 2008). The two-factor breakdown of positive reinforcement motives (social and enhancement) and negative motives (coping) pair with our positive and negative college adjustment variables to parsimoniously capture the relationships between the negative and positive components of these two concepts. These two-motive scales each had high reliability (coping: α=.84; positive motives: α=.95). All responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost never/never) to 5 (almost always/always).

3. Results

3.1. Analytic plan

Path analysis was used to examine negative alcohol consequences as a function of college adjustment, drinking motives, and weekly drinking behavior in college students. All measures were standardized. All analyses are based on cases with complete data; five incomplete cases were excluded. The first model run was saturated wherein negative consequences were specified as a function of positive and negative college adjustment, number of drinks per week, positive reinforcement motives, and coping motives — the full model contained direct and indirect paths to consequences for all factors. The basic model was set up so that: (1) motives predicted college adjustment and were allowed to have direct paths to weekly drinking and consequences, (2) college adjustment predicted consequences and was allowed to have a direct path to weekly drinking, and (3) number of weekly drinks directly predicted consequences. Post-hoc models were run that removed non-significant paths (α=.01). As a final step, a multiple-group path model was run to test sex differences. Maximum likelihood estimation was used to identify all models via EQS (Bentler & Wu, 1998). Due to the number of statistical comparisons, the more stringent alpha level of .01 was utilized for all analyses.

3.2. Sample characteristics

Correlation matrices were based on cases with complete data. Table 1 contains descriptive statistics for the sample and Table 2 shows the correlation matrix separated by sex.

3.3. Final models

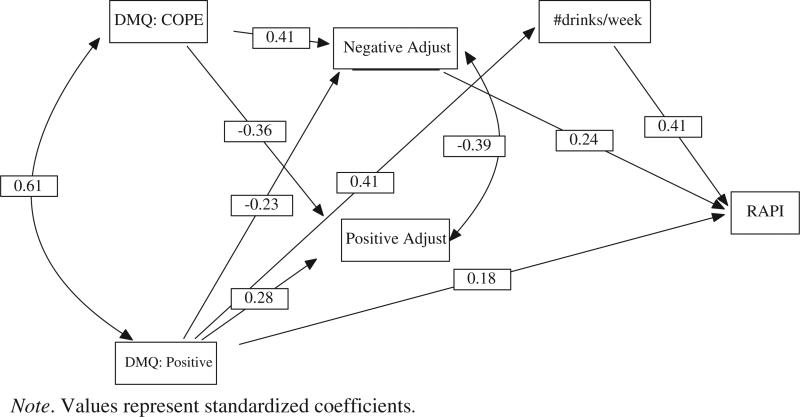

The final model shown in Fig.1 fit the data well, χ2(5, N=253)=2.67, p>.75, CFI=1.00, NFI=.99. All paths shown are significant (α=.01) and labeled with their standardized estimates. Negative consequences was directly predicted by negative college adjustment (β=.24, p>.01; but not positive college adjustment), positive motives (β=.18, p<.002), and drinks per week (β=.41, p<.001). Poorer adjustment to college, stronger positive drinking motivation, and more drinking were all related to increased numbers of consequences. Note that although −.39 is a strong correlation between positive and negative adjustments, it is low enough to suggest that these likely do not represent the same construct.

Fig. 1.

Negative consequences as a function of amount of drinking, types of college adjustment, and drinking motives. Note. Values represent standardized coefficients.

Similar to the overall model, positive reinforcement motives not only directly predicted consequences, but that relationship was modi-fied by the number of drinks per week and the amount of negative college adjustment. Specifically, stronger positive reinforcement motives predicted more drinks consumed per week (β=.41, p<.001) which predicted more negative consequences. Further, stronger positive reinforcement motives predicted less negative adjustment (β=−.23, p<.001) which led to fewer negative consequences. While there was no direct relationship between coping motives and consequences, there was a mediated relationship from coping motives to consequences through negative adjustment. More coping motives were related to more negative adjustment which in turn was related to more negative consequences.

To provide further evidence of mediation, a test of indirect effect was completed for each mediated path in Fig. 1: coping motives’ relationship to RAPI as mediated by negative college adjustment, positive reinforcement motives’ relationship to RAPI as mediated by negative college adjustment, and positive reinforcement motives’ relationship to RAPI as mediated by weekly drinking. The sequence of processes depicted in Fig. 1 supported that the indirect effect was statistically explicated through the mediational variables (ps<.01). The test of indirect effect, calculated using the EQS program, is based on the ideas and formulations proposed for structural equation models by Sobel (1987).

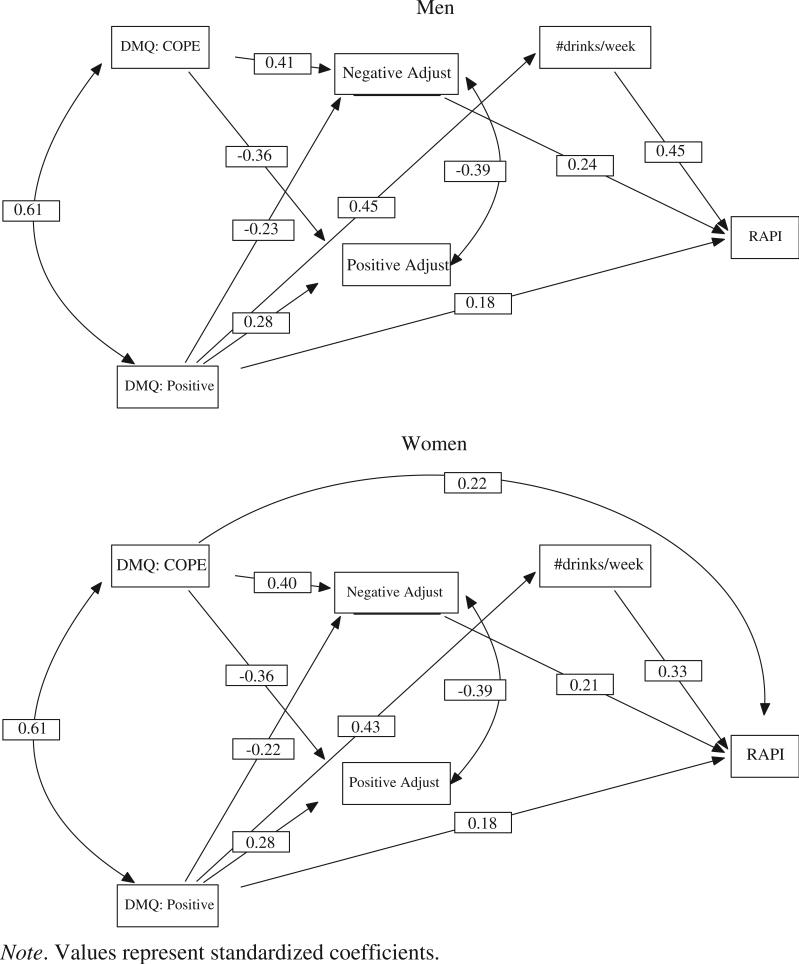

3.4. Sex differences

A multiple-group path analysis was run to test sex differences and resulted in the model shown in Fig. 2; standardized estimates are shown, χ2(24, N=253)=33.09, p>.10, CFI=.98, NFI=.92. There was one major significant difference between men and women: negative consequences were directly predicted by coping motives for women but not for men (βwomen =.22, p<.01), All other paths replicate the previous model. Tests of indirect effects were again completed for each mediated path in Fig. 2. The sequence of processes depicted in Fig. 2 supported that the indirect effect was statistically explicated through the mediational variables (ps<.01).

Fig. 2.

Negative consequences as a function of amount of drinking, types of college adjustment, and drinking motives for men and women. Note. Values represent standardized coefficients.

4. Discussion

This study extends the current understanding of the relationships between drinking motives and negative alcohol-related consequences in several important ways. It is the first study to document the mediational role college adjustment plays in the well-researched, yet inconsistent, association between drinking motives and alcohol consequences. Further, it utilized the novel categorization of both positive and negative college adjustment to show the role these two factors play (or do not play) with regard to alcohol consumption and drinking consequences. Using structural equation modeling, negative college adjustment was found to be directly related to alcohol consequences and had no relationship with alcohol consumption when simultaneously accounting for other variables (i.e., drinking motives, adjustment levels, and negative-alcohol related consequences). Conversely, positive college adjustment was not related to alcohol-related consequences or alcohol consumption. These findings support our hypotheses.

The observed relationships between drinking motives and alcohol-related consequences also hold important implications. Consistent with current research trends (for review see Kuntsche et al., 2005), positive reinforcement drinking motives demonstrated both a direct relationship to consequences as well as an indirect relationship to consequences via association with increased weekly drinking levels. Positive reinforcement motives were also related to positive college adjustment which was not associated with alcohol outcomes. Further, stronger positive reinforcement motives were also related to less negative (or better) adjustment to college and better adjustment was related to fewer alcohol consequences when controlling for drinking. However, this does not indicate that positive reinforcement motives are healthy or beneficial to a student, as positive reinforcement drinking motives in the larger context of the entire model are still particularly risky. Regardless of levels of college adjustment, positive reinforcement motives were directly associated with alcohol-related consequences and were indirectly associated with consequences via alcohol consumption. These results are supported by additional research that has consistently found positive drinking motives, particularly enhancement motives, to be more closely linked to heavy drinking and resulting negative alcohol-related consequences than negative motives (for review, see Kuntsche et al., 2005). On the other hand, the present findings suggest that previous understandings of how coping drinking motives translate to alcohol consequences were incomplete. As anticipated, negative college adjustment mediated the relationship between coping motives and negative alcohol-related consequences, while simultaneously controlling for typical weekly drinking. Recent research has suggested that alcohol consequences are partly based on psychological characteristics such as negative affect, a likely byproduct of poorer college adjustment, rather than just individual drinking behavior (Bonin, McCreary, & Sadava, 2000; Park, 2004; Park & Grant, 2005). These results highlight the importance of negative college adjustment to understanding college student drinking outcomes.

4.1. Gender difference

An important gender difference was also observed. All pathways for males maintained relatively the same strength and significance as the overall model. For women, a direct relationship between coping drinking motives and negative alcohol-related consequences emerged. This direct relationship was unexpected and could indicate the presence of additional mediators in addition to college adjustment. The Student Adjustment to College Questionnaire contains items that aim to capture mental health, anxiety, and stress components of adjustment. Indeed, in their more independent and distinct forms, mental health, social anxiety, and stress have demonstrated unique relationships with alcohol consequences among women (LaBrie et al., 2009; Norberg et al., 2010; Rice & Van Arsdale, 2010). Further, social anxiety may even serve as a protective factor against alcohol consequences for men (Norberg, Norton, Olivier, & Zvolensky, 2010). A formal investigation into these and other potential mediating variables is necessary to determine the underlying mechanisms at play in the relationship between women's coping motives and alcohol consequences. Additionally, research has suggested the RAPI may exhibit a bias for women (leading to higher scores) that may also contribute to the emergence of this new pathway (Earleywine et al., 2008; Neal et al., 2006). Research also indicates that women are more likely to report drinking for coping motives than men (Norberg et al., 2010; Stewart et al., 2001). This increased reporting of coping motives may also contribute to the emergence of the effect.

4.2. Importance of poorer college adjustment

While negative alcohol consequences and their precursors are certainly of concern to student affairs professionals and researchers, so is poorer college adjustment. Difficulties related to college adjustment are cited as a significant factor accounting for the nearly 50% of all college students that leave college without obtaining a degree (ACT, 2002; Kalsner & Pistole, 2003; Kerr et al., 2004; Parker et al., 2004). Our results demonstrate two distinct negative impacts of coping drinking motives: A positive relationship between coping drinking motives and negative college adjustment as well as a negative relationship between coping motives and positive college adjustment.

4.3. Intervention implications

The impacts of alcohol coping strategies on both college adjustment and negative alcohol-related consequences have significant implications for the design and implementation of college alcohol interventions. By confirming that coping motives are indeed related to negative alcohol-related consequences (as mediated by negative college adjustment), existing intervention and prevention programs may be benefited by incorporating programmatic components aimed at addressing problematic drinking motives. The positive effects of this incorporation may be two-fold. For example, research has shown that despite pre-established drinking motives, the use of protective behavioral strategies (e.g., counting number of drinks) can lead to reductions in drinking and therefore related consequences (LaBrie, Hummer, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2010). Thus, teaching students ways to increase their use of protective behavioral strategies could mitigate the harm associated with coping-motivated drinking. Additionally, specifically addressing the use of alcohol to cope with stress (by either modifying the stressful student environment or teaching students healthy coping mechanisms) would have the added benefit of improving a student's adjustment to college which in itself carries significant benefits for the student aside from decreased alcohol consequences. Orientation and first-year student programs typically strive to integrate healthy habits into the student lifestyle and are common across most colleges. School administrators may wish to use this venue to address the risk associated with using alcohol as a coping mechanism and potentially even identify students already reporting frequent coping-motivated drinking behavior.

4.4. Limitations

This study must be viewed in light of several limitations. This is the first study to operationalize positive and negative college adjustment. While the two-factor adaptation made to the Student Adjustment to College Questionnaire was found to be reliable, the questionnaire should be considered a pilot instrument that warrants further examination. This study also employed a cross-sectional design. Although conceptually reinforced, the temporal ordering of motives preceding adjustment cannot be fully determined. While this paper draws upon relevant research to propose that a third factor, college adjustment, can mediate the relationship between motives and alcohol outcomes, this claim is not definitive. One possibility is that drinking motives could mediate the link between college adjustment and drinking outcomes. Additionally, drinking motives and college adjustment may have bi-directional associations with each other in the context of alcohol-related outcomes. Future research would benefit by longitudinally assessing drinking motives and their relationship to collegiate adjustment, alcohol consumption, and alcohol related consequences after arriving on campus and throughout a student's college tenure.

4.5. Conclusion

This study offers unique contributions to our understanding of drinking motives and college adjustment. It is the first study to show that the relationship between coping drinking motives and alcohol consequences is mediated by negative college adjustment. Further, it shows that positive college adjustment, while related to positive reinforcement drinking motives, is not directly related to alcohol-related outcomes. Moreover, coping motives were found to be directly predictive of negative alcohol-related consequences among women, signifying the need to garner a better understanding of how and why this unique risk is present for college women. Finally, the results identify implications for the design and content of college-student alcohol interventions to mitigate harmful consequences of coping drinking motives.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics for sample with complete data for relevant variables.

| Variable | Male (n = 101) |

Female ( n = 152) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | |

| Age | 18.90 | (1.00) | 19.10 | (1.90) |

| RAPI | 3.21 | (5.27) | 3.38 | (5.31) |

| Typical weekly drinks | 10.33 | (12.43) | 6.28 | (6.30) |

| Positive motives | 2.91 | (1.19) | 2.86 | (1.20) |

| Coping motives | 1.75 | (0.88) | 1.83 | (0.86) |

| College adjustment – negative | 117.4 | (37.2) | 126.3 | (39.4) |

| College adjustment – positive | 161.5 | (29.6) | 160.6 | (34.3) |

Table 2.

Correlation matrix for men and women.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.RAPI | - | .54* | .33* | –.10 | .39* | .24† |

| 2.Typical weekly drinks | .58* | - | .14 | –.10 | .39* | .24† |

| 3.Adjustment – negative | .18† | –.04 | - | –.50* | .07 | .28† |

| 4.Adjustment – positive | –.05 | –.05 | –.39* | - | .07 | –.20† |

| 5.Positive motives | .37* | .43* | –.01 | .07 | - | .60* |

| 6.Coping motives | .35* | .31* | .28* | –.17† | .57* | - |

Note: Men are above the diagonal and women are below.

p<.05.

p<.01.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

This research was funded by Grant R01 AA 012547-06A2 from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), Grant Q184H070017 from the U.S. Department of Education.

Neither the NIAAA nor DOE had a role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Appendix

Appendix Table A.1.

SACQ two-factor item assignment.

| Positive college adjustment items α = .930, n = 25 | Negative college adjustment items α = .918, n = 30 |

|---|---|

| I feel that I fit in well as part of the college environment. | I haven't been able to control my emotions very well lately. |

| I have been keeping up to date on my academic work. | Iam finding academic work at college difficult. |

| I am meeting as many people, and making as many friends as I would like at college. | I feel I am very different from other students at college in ways that I don't like. |

| I know why I am in college and what I want out of it. | I have felt tired much of the time lately. |

| I am very involved with social activities in college. | Lately I have been feeling blue and moody a lot. |

| I am adjusting well to college. | I'm not working as hard as I should at my coursework |

| I am satisfied with the level at which I am performing academically. | Lately I have been giving a lot of thought to transferring to another college. |

| I have had informal, personal contact with college professors. | I am having difficulty feeling at ease with other people at college. |

| I am pleased now about my decision to go to college. | I have been having lots of headaches lately. |

| I am pleased now about my decision to attend this college in particular. | I am having a lot of trouble getting started on homework assignments. |

| I am satisfied with the extent to which I am participating in social activities at college. | I'm not really smart enough for the academic work I am expected to be doing right now. |

| My academic goals and purposes are well defined. | I worry a lot about my college expenses. |

| Getting a college degree is important to me. | I have been feeling tense of nervous lately. |

| My appetite has been good lately. | I wish I were at another college or university. |

| I am satisfied with the extracurricular activities available at college. | Recently I have had trouble concentrating when I try to study. |

| I feel I have enough social skills to get along well in the college setting. | I'm not doing well enough academically for the amount of work I put in. |

| I am attending classes regularly. | I've put on (or lost) too much weight recently. |

| I have several close social ties at college. | I haven't been sleeping very well. |

| I am enjoying my academic work at college. | I have been getting angry easily lately. |

| I feel I have good control over my life situation at college. | I really haven't had much motivation for studying lately. |

| I have been feeling in good health lately. | Sometimes my thinking gets muddled up too easily. |

| I have some good friends of acquaintances at college with whom I can talk about any problems I may have. | Most of the things I am interested in are not related to any of my course work at college. |

| I am quite satisfied with my social life at college | I have been feeling lonely a lot at college lately |

| I am quite satisfied with my academic situation at college. | I haven't been very efficient in the use of study time lately. |

| I feel confident that I will be able to deal in a satisfactory manner with future challengers here at college. | I have given a lot of thought lately to whether I should ask for help from the Psychological/Counseling Services Center of from a psychotherapist outside of college. |

| Being on my own, taking responsibility for myself, has not been easy. | |

| Lately I have been having doubts regarding the value of a college education. | |

| Lately I have been giving a lot of thought to dropping out of college altogether and for good. | |

| I find myself giving considerable thought to taking time off from college and finishing later.. | |

| I am experiencing a lot of difficulty coping with the stresses imposed upon me in college. |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier's archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

Contributors

Joseph LaBrie, Phillip Ehret, Justin Hummer, and Katherine Prenovost have each contributed significantly to this manuscript. Specifically, Dr. LaBrie generated the idea for the study and oversaw its production. Dr. LaBrie and Justin Hummer designed the study and wrote the protocol. Katherine Prenovost performed the statistical analyses and drafted the results section. Phillip Ehret developed the specific hypotheses tested, performed the literature review, and, along with Dr. LaBrie and Justin Hummer, contributed to writing all sections of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- ACT College graduation rates steady despite increase in enrollment. 2002 Nov; http:www.act.org/news.

- Baker RW, Siryk B. Measuring adjustment to college. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1984;31(2):179–189. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.31.2.179. [Google Scholar]

- Baker RW, Siryk B. Exploratory intervention with a scale measuring adjustment to college. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1986;33(1):31–38. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.33.1.31. [Google Scholar]

- Baker RW, Siryk B. Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Baker R, Siryk B. SACQ: Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire Manual. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Wu EJC. EQS for Windows 5.7b. Multivariate Software Inc; Encino, CA, New York: Aug, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bonin MF, McCreary DR, Sadava SW. Problem drinking behavior in two community-based samples of adults: Influence of gender, coping, loneliness, and depression. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2000;14(2):151–161. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.14.2.151. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.14.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bray NJ, Braxton JM, Sullivan AS. The influence of stress-related coping strategies on college student departure decisions. Journal of College Student Development. 1999;40(6):645–657. [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58(1):100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66(1):184–195. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.184. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LM, Graham JW, Hansen WB, Johnson C. Agreement between retrospective accounts of substance use and earlier reported substance use. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1985;9(3):301–309. doi:10.1177/014662168500900308. [Google Scholar]

- Conti R. College goals: Do self-determined and carefully considered goals predict intrinsic motivation, academic performance, and adjustment during the first semester? Social Psychology of Education. 2000;4:189–211. doi:10.1023/A:1009607907509. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M, Russell M, Skinner JB, Windle M. Development and validation of a three-dimensional measure of drinking motives. Psychological Assessment. 1992;4(2):123–132. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.4.2.123. [Google Scholar]

- Cox W, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1988;97(2):168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox W, Klinger E. Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use: A model. In: Cox WM, editor. Why people drink: Parameters of alcohol as a reinforcer. Amereon Press; New York: 1990. pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Dimeff LA, Baer JS, Kivlahan DR, Marlatt G. Brief Alcohol Screening and Intervention for College Students (BASICS): A harm reduction approach. Guilford Press; New York: NY US: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson R, Renk K. Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(10):1231–1244. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20295. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earleywine M, LaBrie JW, Pedersen ER. A brief Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index with less potential for bias. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(9):1249–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.006. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Bacon AK, Garcia TA. Drinking motives as mediators of social anxiety and hazardous drinking among college students. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(3):133–145. doi: 10.1080/16506070802610889. doi:10.1080/16506070802610889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertel J. College student generational status: Similarities, differences, and factors in college adjustment. Psychological Record. 2002;52:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson R, Edwards E, Heeren T, Rosenbloom D. Age of drinking onset and injuries, motor vehicle crashes, and physical fights after drinking and when not drinking. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(5):783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00896.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00896.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Zakocs RC, Kopstein A, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U. S. college students ages 18–24. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(2):136–144. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalsner L, Pistole MC. College adjustment in a multiethnic sample: Attachment, separation-individuation, and ethnic identity. Journal of College Student Development. 2003;44:92–109. doi:10.1353/csd.2003.0006. [Google Scholar]

- Kassel JD, Jackson SI, Unrod M. Generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation and problem drinking among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(2):332–340. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr S, Johnson VK, Gans SE, Krumrine J. Predicting adjustment during the transition to college: Alexithymia, perceived stress, and psychological symptoms. Journal of College Student Development. 2004;45:593–611. doi:10.1353/csd.2004.0068. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Cooper M. Drinking to have fun and to get drunk: Motives as predictors of weekend drinking over and above usual drinking habits. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;110(3):259–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.021. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Bullying and fighting among adolescents — Do drinking motives and alcohol use matter? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(12):3131–3135. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.003. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Engels R, Gmel G. Drinking motives as mediators of the link between alcohol expectancies and alcohol use among adolescents. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(1):76–85. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25(7):841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe R, Gmel G, Engels R. Replication and validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised (DMQ-R, Cooper, 1994) among adolescents in Switzerland. European Addiction Research. 2006;12(3):161–168. doi: 10.1159/000092118. doi:10.1159/000092118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(4):343–349. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Pedersen ER. Reasons for drinking in the college student context: The differential role and risk of the social motivator. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(3):393–398. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Kenney SR, Lac A, Garcia JA, Ferraiolo P. Mental and social health impacts the use of protective behavioral strategies in reducing risky drinking and alcohol consequences. Journal of College Student Development. 2009;50(1):35–49. doi: 10.1353/csd.0.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie JW, Lac A, Kenney SR, Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: Gender and race differences. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(4):354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrie J, Lamb T, Pedersen E. Changes in drinking patterns across the transition to college among first-year college males. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2008;18(1):1–15. doi: 10.1080/15470650802526500. doi:10.1080/15470650802526500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larimer ME, Turner AP, Anderson BK, Fader JS, Kilmer JR, Palmer RS, et al. Evaluating a brief alcohol intervention with fraternities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(3):370–380. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Geisner IM, Patrick ME, Neighbors C. The social norms of alcohol-related negative consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(2):342–348. doi: 10.1037/a0018020. doi:10.1037/a0018020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong FL, Bonz MH, Zachar P. Coping styles as predictors of college adjustment among freshmen. Counseling Psychology Quarterly. 1997;10(2):211–220. doi: 10.1080/09515079708254173. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Phillippi J, Neighbors C. Morally based self-esteem, drinking motives, and alcohol use among college students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(3):398–403. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.398. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.21.3.398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyvers M, Hasking P, Hani R, Rhodes M, Trew E. Drinking motives, drinking restraint and drinking behaviour among young adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(2):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt G, Baer J, Kivlahan DR, Dimeff LA, Larimer ME, Quigley LA, et al. Screening and brief intervention for high-risk college student drinkers: Results from a 2-year follow-up assessment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:604–615. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.4.604. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.66.4.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Cimini M. Do protective behavioral strategies mediate the relationship between drinking motives and alcohol use in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(1):106–114. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Lee CM, Oster-Aaland L, Larimer ME. The roles of negative affect and coping motives in the relationship between alcohol use and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(3):412–419. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Rocha TL, Martin JL, Serrao HF. Drinking motives and college students: Further examination of a four-factor model. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(2):289–295. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.289. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24(4):705–711. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. doi:10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . A call to action: Changing the culture of drinking at U.S. colleges (NIH Publication No. 02-5010) Author; Rockville, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Corbin WR, Fromme K. Measurement of alcohol-related consequences among high school and college students: Application of item response models to the Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index. Psychological Assessment. 2006;18(4):402–414. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.402. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norberg MM, Norton AR, Olivier J, Zvolensky MJ. Social anxiety, reasons for drinking, and college students. Behavior Therapy. 2010;41:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.002. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl. 14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Positive and negative consequences of alcohol consumption in college students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(2):311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Grant C. Determinants of positive and negative consequences of alcohol in college students: Alcohol use, gender, and psychological characteristics. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30(4):755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Levenson MR. Drinking to cope among college students: Prevalence, problems and coping processes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(4):486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker J, Summerfeldt L, Hogan M, Majeski S. Emotional intelligence and academic success: Examining the transition from high school to university. Personality and Individual Differences. 2004;36(1):163–172. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00076-X. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JH, Hurtado S, DeAngelo L, Palucki Blake L, Tran S. The American freshman: National norms fall 2010. Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA; Los Angeles: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2003;17(1):13–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.17.1.13. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice KG, Van Arsdale AC. Perfectionism, perceived stress, drinking to cope, and alcohol-related problems among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2010;57(4):439–450. doi:10.1037/a0020221. [Google Scholar]

- Schulenberg J, Maggs JL, Long SW, Sher KJ, Gotham HJ, Baer JS, et al. The problem of college drinking: Insights from a developmental perspective. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research. 2001;25(3):473–477. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2001.tb02237.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ, Wood MD, Wood PK, Raskin G. Alcohol outcome expectancies and alcohol use: A latent variable cross-lagged panel study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105(4):561–574. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.105.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB. A comparison of motives for marijuana and alcohol use among experienced users. Addictive Behaviors. 2000;25(1):153–160. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00104-x. doi:10.1016/S0306-4603(98)00104-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Direct and indirect effects in linear structural equation models. Sociological Methods & Research. 1987;16:155–176. doi:10.1177/0049124187016001006. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart SH, Zvolensky MJ, Eifert GH. Negative-reinforcement drinking motives mediate the relationship between anxiety sensitivity and increased drinking behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;31:157–161. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00213-0. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor MA, Pastor DA. A confirmatory factor analysis of the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2007;67(6):1002–1018. doi:10.1177/0013164406299125. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Lee J, Kuo M, Seibring M, Nelson TF, Lee H. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Journal of American College Health. 2002;50(5):203–217. doi: 10.1080/07448480209595713. doi:10.1080/07448480209595713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study: Focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein L, Laverghetta A. College student stress and satisfaction with life. College Student Journal. 2009;43(4, PtA):1161–1162. [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the assessment of adolescent problem drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50:30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]