Most breast cancer patients want to discuss costs of care, but there is little consensus on the desired content or goal of these discussions. A self-administered, anonymous survey was given to breast cancer patients presenting for a routine visit within 5 years of diagnosis at an academic cancer center. Survey questions addressed experience and preferences concerning discussions of cost and views on cost control. Results are primarily descriptive.

Keywords: Neoplasm, Health care costs, Drug costs, Cost of illness, Health care disparities

Abstract

Background.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology views patient-physician discussion of costs as a component of high-quality care. Few data exist on patients’ views regarding how cost should be addressed in the clinic.

Methods.

We distributed a self-administered, anonymous, paper survey to consecutive patients with breast cancer presenting for a routine visit within 5 years of diagnosis at an academic cancer center. Survey questions addressed experience and preferences concerning discussions of cost and views on cost control. Results are primarily descriptive, with comparison among participants on the basis of disease stage, using chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests. All p values are two-sided.

Results.

We surveyed 134 participants (response rate 86%). Median age was 61 years, and 28% had stage IV disease. Although 44% of participants reported at least a moderate level of financial distress, only 14% discussed costs with their doctor; 94% agreed doctors should talk to patients about costs of care. Regarding the impact of costs on decision making, 53% felt doctors should consider direct costs to the patient, but only 38% felt doctors should consider costs to society. Moreover, 88% reported concern about costs of care, but there was no consensus on how to control costs.

Conclusion.

Most breast cancer patients want to discuss costs of care, but there is little consensus on the desired content or goal of these discussions. Further research is needed to define the role of cost discussions at the bedside and how they will contribute to the goal of high-quality and sustainable cancer care.

Implications for Practice:

The 2009 American Society of Clinical Oncology cost of cancer care guidance statement recommends that physicians and patients should communicate about costs as a means of decreasing overall spending and minimizing patients’ financial burden. Our study suggests that the impact of costs of breast cancer care can be profound and that patients want to discuss direct out-of-pocket costs with their oncologists in the clinic. Our study also finds that patient-physician communication about the societal costs of cancer care is not widely accepted by patients. Whether such discussions should occur or will have any role in controlling health care spending remains to be determined.

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health estimates that total spending on cancer care will grow from $125 billion in 2010 to more than $200 billion in 2020, with an increase from $16.5 billion in 2010 to $20.5 billion in 2020 on total spending for breast cancer alone [1]. Both the total costs of breast cancer care and costs per patient are projected to increase over this period [2]. The rising costs of care are viewed as unsustainable both at the societal level and for individual patients, who are experiencing increasing out-of-pocket costs [3, 4]. High out-of-pocket costs lead to increased financial hardship, which affects care choices, quality of life, and disease outcomes [5, 6].

Recognizing the importance of these issues, the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) issued a guidance statement recommending that practicing oncologists directly confront costs of care in the clinic. This guidance statement highlighted physician-patient communication about costs as a key component to decreasing both total cancer spending and cancer patients’ financial burden [7].

Although a growing body of literature demonstrates that patients experience financial burdens from the diagnosis of cancer and the costs of care, there has been relatively little investigation of the current role of discussions of cost in the clinic, how discussions of cost affect care and decision making, and the participants’ perspectives on the desirability and goals of such discussions. Within the context of a breast cancer clinic, we sought to understand patients’ experiences with and attitudes toward discussions of costs of care.

Materials and Methods

In autumn 2012, we distributed a cross-sectional, self-administered, anonymous, paper survey to consecutive breast cancer participants presenting for a routine visit at Duke University Medical Center. Eligible participants were female, English-speaking patients older than 18 years of age with a diagnosis of breast cancer and who were within 5 years from their initial diagnosis of breast cancer. The study is shown in the supplemental online Appendix.

Study-specific survey questions were developed based on a literature review and the authors’ experience. These questions were tested among a pilot cohort of 10 participants and then refined for content and clarity. In addition, the validated InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale (IFDFW) was used to assess financial distress [8]. Survey domains included demographics, desired and actual timing and content of patient-physician discussions about costs, barriers to these discussions, and views concerning methods of cost containment in cancer care. Consecutive participants were offered the survey by clinic staff for a period of 12 weeks, and response rate was calculated based on participants completing and returning the survey.

Given the primarily descriptive goals of this study, bivariate analyses of dichotomous categorical data were performed using chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Mantel-Haenszel tests were performed on ordinal variables with more than two levels. For selected questions, simple linear and logistic regression methods were used to determine associations of interest such as comparisons based on age, disease stage, income, race, and the IFDFW. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, http://www.sas.com) was used for statistical analyses.

Results

A total of 156 consecutive participants were offered the survey, and 134 participants completed it, for a response rate of 86%.

Demographics

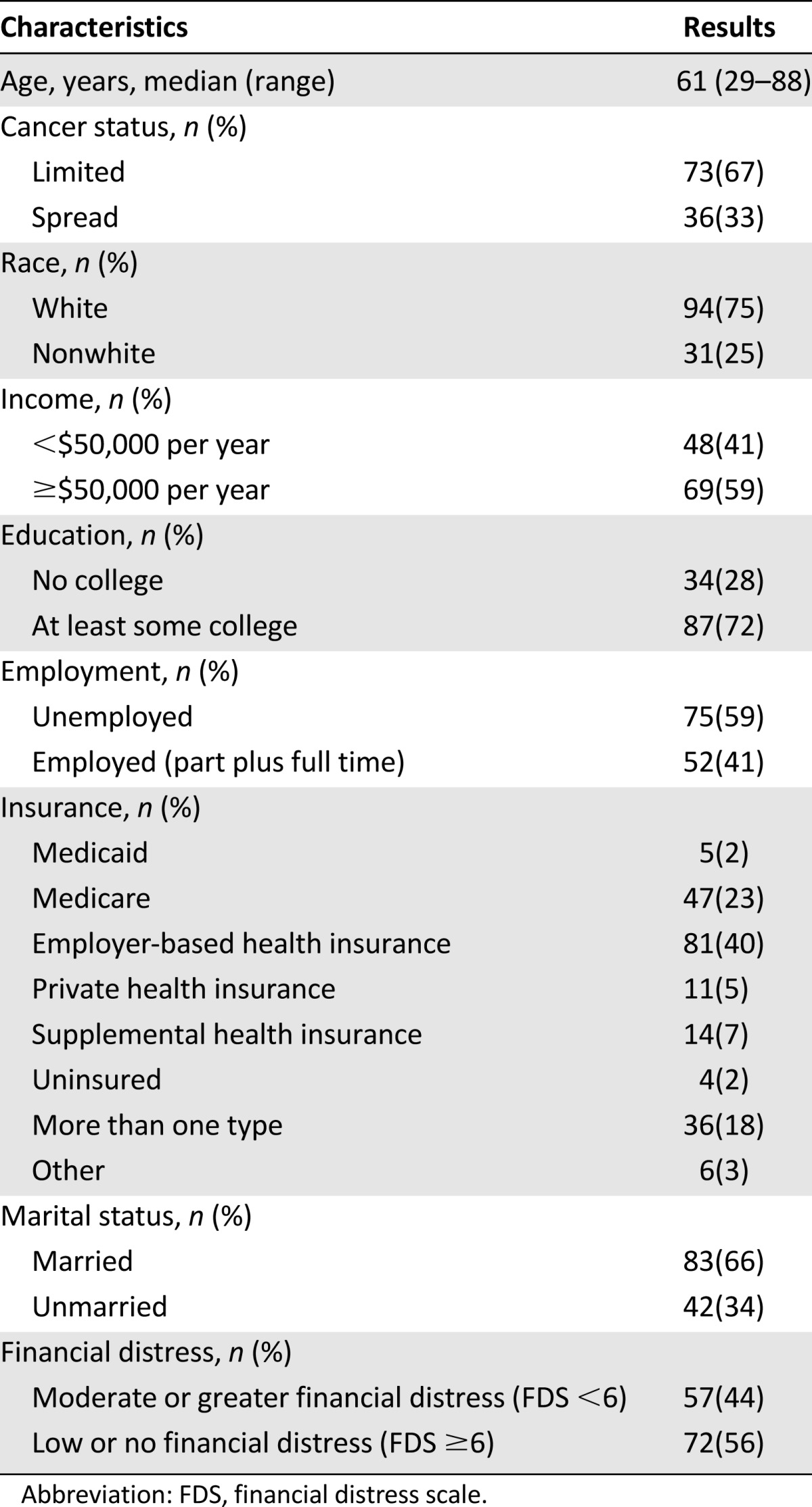

The demographics of respondents are outlined in Table 1. Most participants were white (75%), well educated (72% had at least some college education), insured (98%), and married (66%). From a socioeconomic perspective, most respondents (59%) had an annual income of $50,000 per year or higher and scored low or none on the IFDFW financial distress scale (56%). In terms of employment status, 33% (n = 44) were employed full time, 7% (n = 9) were employed part time, and 41% (n = 53) were retired. Most participants reported receiving assistance in paying for their cancer care (77%, n = 99). Most respondents had a history of local rather than metastatic disease (67% vs 33%). Forty-six percent (n = 59) were receiving anticancer treatment at the time of the survey.

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics

Experience With Discussions Concerning Costs

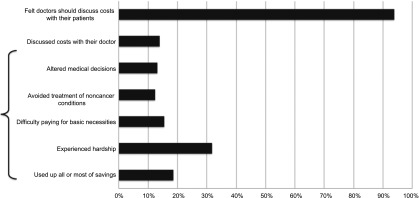

Although 94% (n = 121) of respondents wanted to discuss costs of care with their doctor, only 14% (n = 18) reported having had such discussions (Fig. 1). Consistent with the low number of discussions reported, most participants felt poorly informed about the costs of their care (67%, n = 87), and a significant number reported surprise at high costs (40%, n = 52) or did not understand the costs of their care (29%, n = 38).

Figure 1.

Patient desire to discuss costs and reported impact of costs.

One-third of participants (32%, n = 41) reported hardship as a result of their cancer costs, with 16% (n = 20) reporting difficulty paying for basic necessities and 19% (n = 24) reporting using up all or most of their savings. We did not assess the details of respondents’ decision making, but 13% (n = 17) reported changing their medical decisions as a result of the costs of their care, and 12% (n = 16) avoided treatment of non-cancer-related health issues because of costs. As might be expected, participants with moderate or greater financial distress (IFDFW <6) were statistically significantly more likely than those with less financial distress to have hardship and to make sacrifices as a result of their financial distress (Fig. 1).

Most participants reported that costs outside of their direct out-of-pocket costs or the “costs to Medicare, society or their insurance company” did not affect their medical decisions (85%, n = 110); however, most participants also reported that they did not understand the costs to society with regard to their care (64%, n = 82).

Patient Interest in Discussing Costs of Care

In terms of the desired timing of discussions, most respondents did not feel that physicians should initiate a conversation about costs at every visit (n = 107, 83%). Instead, respondents felt that physicians should wait for the patient to initiate the conversation (n = 80, 62%) or only initiate a conversation about costs when a new treatment was being considered (47%, n = 61). Only a minority of participants (n = 27, 21%) felt missing medications or visits should prompt a physician-patient discussion about costs.

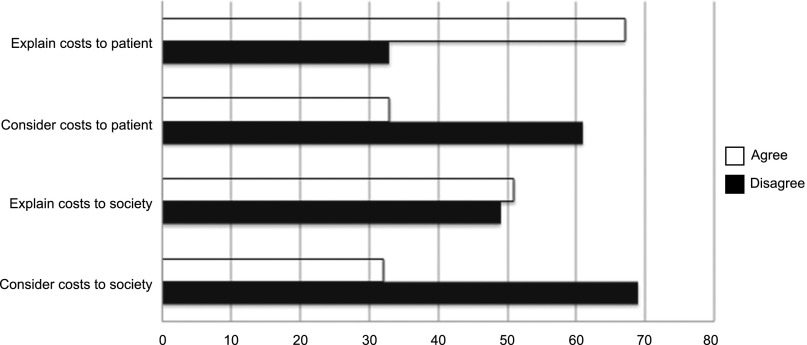

In terms of the desired content of the discussion (Fig. 2), most respondents (53%, n = 69) felt doctors should explain to each patient his or her out-of-pocket costs. Respondents were divided in terms of their interest in having doctors talk to them about the costs to society with regard to a given treatment plan (n = 49, 38% agree; n = 51, 40% disagree).

Figure 2.

Desired content for discussion of costs.

There was no association of these content and timing responses with stage of disease, financial distress, status of treatment, or age.

Views on Reduction of Societal Costs of Cancer Care

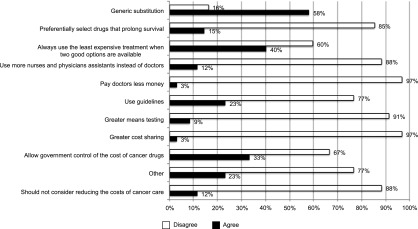

Most participants (88%) were concerned about the costs of cancer care; however, when asked about specific strategies for controlling costs, there was little agreement about which methods might succeed (Fig. 3). Although most respondents (58%) agreed with generic substitution, only a minority or respondents endorsed other cost-controlling measures such as preferential selection of drugs that prolong survival (15%), using more physician assistants and nurses (12%), paying doctors less (3%), greater means testing (9%), or greater cost sharing (3%).

Figure 3.

Preferences for control of costs of cancer care.

Most respondents did not want their doctor thinking about cost-controlling measures. In addition, 52% (n = 67) of respondents disagreed with the statement “when choosing a new treatment, doctors should consider the amount of money it will cost the insurance company or government.”

Participants with metastatic cancer were significantly less likely (unadjusted) than those with curable disease to want doctors to consider societal costs (33% [n = 24] vs 6% [n = 2]; p < .01) and more likely to agree that society should pay for treatments even if they do not prolong survival (p < .05).

Discussion

The importance of high and rising costs in health care in general and in cancer care in particular have been recognized. High costs of care threaten the competitiveness of U.S. industry and reduce funds available for other societal priorities. High costs also have a direct impact on patients in terms of access to care [9], financial distress [10], decision making [6], well-being [11], and disease outcomes [12, 13]. Our study confirms that patients with breast cancer experience substantial financial distress, based on the IFDFW, with corresponding detriments in well-being (altered spending on basic necessities and leisure, drained savings) and medical care (altered oncologic and nononcologic treatment choices).

Because of the profound, multidimensional impact of costs on patients and society, ASCO and others have pointed out the importance of discussing costs of care in the clinic [14, 15]. This study suggests that clinicians, researchers, and policy makers need to be very clear about the distinct issues of controlling direct costs to patients and controlling overall health care spending and similarly clear about the content and goal of discussions of cost in the clinic

Making discussion of a patient’s out-of-pocket costs a standard component of the patient-physician encounter appears to be both feasible and desirable, given that the majority of patients in our study reported wanting to understand and discuss costs of their care with their oncologist and cited no barriers to such a discussion. The fact that we found that few patients reported cost discussions despite patients’ interest suggests that physicians may not be aware of this interest, may not feel prepared to discuss costs, or may feel that it is inappropriate or not a priority for the clinic visit. Our study shows that the limitations to cost discussions cited in previous oncologist surveys, namely, lack of time and knowledge, are not limitations perceived by patients [16].

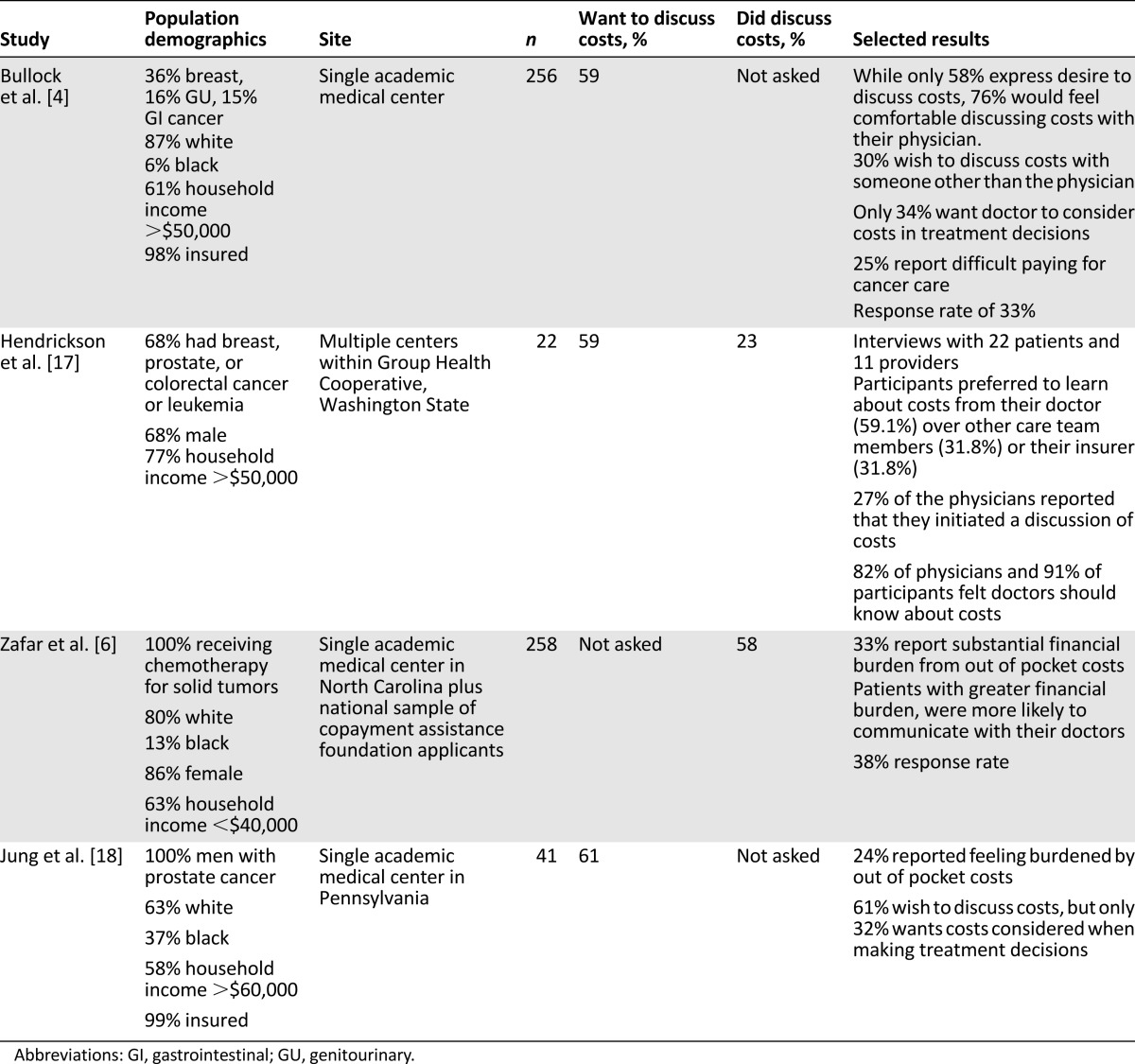

There is a need for some caution in assuming that all patients desire discussions of cost in the oncology clinic. Not all patients in our study reported such interest, and our research and other literature suggest that the degree of interest and the content and timing of any discussions of cost vary by individual preference, by patient characteristics, and by setting. Unlike our study, a survey of cancer patients by Bullock et al. found that the many patients (41%) did not want to discuss their out-of-pocket costs with their doctor [4]. Differences in the results of our studies may reflect differences in the study populations; unlike our study, the study by Bullock et al. included all solid-tumor malignancies, male and female patients, and patients who were past 5 years from their diagnosis. Another reason for the differences may be the rapidly evolving public attitudes toward discussing costs of care in the few years since that study and our own. Table 2 summarizes the results and key findings from four other studies of discussions of costs of cancer identified in the literature [4, 6, 17, 18]. Of note, only the study by Zafar et al. included a majority of patients making less than the median U.S. household income [6].

Table 2.

Studies evaluating patient attitudes toward discussing costs of cancer care

Addressing societal costs within a patient-physician interaction appears more controversial than discussing out-of-pocket costs. Although the majority of participants are concerned about the costs of cancer to society at large, the majority do not want to talk with their doctor about these costs. The vast majority do not want their doctor to consider the costs to society when selecting a cancer treatment. This sentiment is even more pronounced among the sickest patients with metastatic disease.

Unlike previous studies, we also assessed patients’ views on many of the most commonly proposed methods of cost control in cancer care such as preferential selection of drugs that prolong survival, use of physician extenders, paying doctors less, greater means testing, and greater cost sharing. Other than generic substitution, the majority of participants did not support any of these proposed solutions.

Our study has several limitations. This was a self-administered questionnaire and measured reported financial distress and discussions of cost, not actual out-of-pocket costs from medical record review or recorded transcripts of clinic visits. It is possible that questions of cost, or at least ability to pay or fill prescriptions, was addressed in the clinic but not perceived as a discussion of costs of care. Other limitations include the study’s small size, restriction to patients with breast cancer, and conduct at a single institution. In addition, the population was largely insured, and almost 60% reported household income of more than $50,000 per year. However, our survey included a diverse population, with 25% nonwhite participants and patients with both early and advanced disease. The fact that, even among a relatively affluent population, a high percentage reported concern with costs of care and interest in discussing costs suggests that this consideration may be important for all patients.

Conclusion

Our study reveals that discussing societal costs of care in the clinic is not desired by patients and that urging clinicians to initiate such discussions is likely not a viable solution to controlling health care costs. Control of costs of cancer care remains an important goal and is directly related to the sustainability of quality and accessible care. If our findings are valid across a broad spectrum of patients with cancer, cost control efforts may be most successful if they are implemented outside of the clinic, at the level of the institution, the payer, and the state. Efforts such as those under way in the U.K. to consider value-based pricing may be part of the solution [19–21]. It appears that current efforts at bedside cost control should be directed at clinicians, who can take several steps to educate themselves to ensure they practice evidence-based care that controls cancer care costs while maintaining or even improving quality [22, 23].

Whether direct conversations with patients, at any level, about societal costs of cancer care will have a role in controlling health care spending remains to be determined. Such conversations would need to occur in a context that is acceptable to patients and consistent with the physicians’ fiduciary responsibility to place the interests of the patient first. Further research can help explore the potential for discussing costs and raising awareness of the costs of care among both physicians and patients to affect societal costs of care, regardless of whether that is the focus of bedside conversations. Ongoing research is evaluating the optimal timing, content, focus, and impact of discussions of costs of cancer care in the clinic. Much the focus of such research is on the “financial toxicity” that treatment decisions can yield in terms of direct out-of-pocket costs to patients [6]. There is a need to determine whether emerging interventions designed to improve patient understanding of costs and to lower out-of-pocket expenses also affect societal expenses and to what degree. Research is also needed to further explore the impact of cost discussions on patient satisfaction and financial distress and the relatively unexplored areas of potential impact on the doctor-patient relationship, access to care, and informed decision making.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Jeffrey Peppercorn and S. Yousuf Zafar are supported by the Greenwall Foundation for Bioethics.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Blair Irwin, Ivy Altomare, Kevin Houck, S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey Peppercorn

Provision of study material or patients: Blair Irwin, Ivy Altomare, Kevin Houck, S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey Peppercorn

Collection and/or assembly of data: Blair Irwin, Gretchen Kimmick, Ivy Altomare, Kevin Houck, S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey Peppercorn

Data analysis and interpretation: Blair Irwin, Ivy Altomare, P. Kelly Marcom, Kevin Houck, S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey Peppercorn

Manuscript writing: Blair Irwin, Gretchen Kimmick, Ivy Altomare, P. Kelly Marcom, Kevin Houck, S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey Peppercorn

Final approval of manuscript: Blair Irwin, Gretchen Kimmick, Ivy Altomare, P. Kelly Marcom, Kevin Houck, S. Yousuf Zafar, Jeffrey Peppercorn

Disclosures

Gretchen Kimmick: Wyeth, GlaxoSmithKline, Bristol-Meyer Squibb, Bionovo (RF); Jeffrey Peppercorn: Novartis (RF); GlaxoSmithKline (E [spouse], OI [spouse]); S. Yousuf Zafar: Genentech (C/A). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.Mariotto AB, Yabroff KR, Shao Y, et al. Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:117–128. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, et al. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:888–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidoff AJ, Erten M, Shaffer T, et al. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure burden for Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1257–1265. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bullock AJ, Hofstatter EW, Yushak ML, et al. Understanding patients’ attitudes toward communication about the cost of cancer care. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:e50–e58. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eichholz M, Pevar J, Bernthal T. Perspectives on the financial burden of cancer care: Concurrent surveys of patients (Pts), caregivers (CGs), and oncology social workers (OSWs) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl):9111a. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zafar SY, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: A pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient’s experience. The Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meropol NJ, Schrag D, Smith TJ, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology guidance statement: The cost of cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3868–3874. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B, et al. The InCharge Financial Distress/Financial Well-Being Scale: Establishing validity and reliability. Proc Assoc Financial Counseling Planning Education. 2006;17:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoen C, Osborn R, Squires D, et al. How health insurance design affects access to care and costs, by income, in eleven countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:2323–2334. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zullig LL, Peppercorn JM, Schrag D, et al. Financial distress, use of cost-coping strategies, and adherence to prescription medication among participants with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9:60s–63s. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.000971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nekhlyudov L, Madden J, Graves AJ, et al. Cost-related medication nonadherence and cost-saving strategies used by elderly Medicare cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:395–404. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0188-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hong J, Reed C, Novick D, et al. Clinical and economic consequences of medication non-adherence in the treatment of patients with a manic/mixed episode of bipolar disorder: Results from the European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication (EMBLEM) study. Psychiatry Res. 2011;190:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heisler M, Choi H, Rosen AB, et al. Hospitalizations and deaths among adults with cardiovascular disease who underuse medications because of cost: A longitudinal analysis. Med Care. 2010;48:87–94. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c12e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shih YC, Ganz PA, Aberle D, et al. Delivering high-quality and affordable care throughout the cancer care continuum. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:4151–4157. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.51.0651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sullivan R, Peppercorn J, Sikora K, et al. Delivering affordable cancer care in high-income countries. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:933–980. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schrag D, Hanger M. Medical oncologists’ views on communicating with patients about chemotherapy costs: A pilot survey. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:233–237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henrikson NB, Tuzzio L, Loggers ET, et al. Patient and oncologist discussions about cancer care costs. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:961–967. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2050-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung OS, Guzzo T, Lee D, et al. Out-of-pocket expenses and treatment choice for men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2012;80:1252–1257. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2012.08.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Claxton K, Briggs A, Buxton MJ, et al. Value based pricing for NHS drugs: An opportunity not to be missed? BMJ. 2008;336:251–254. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39434.500185.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hawkes N. NICE to set out how it will judge social benefits of drugs. BMJ. 2014;348:g370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Linley WG, Hughes DA. Societal views on NICE, cancer drugs fund and value-based pricing criteria for prioritising medicines: A cross-sectional survey of 4118 adults in Great Britain. Health Econ. 2013;22:948–964. doi: 10.1002/hec.2872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramsey SD, Ganz PA, Shankaran V, et al. Addressing the American health-care cost crisis: Role of the oncology community. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1777–1781. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schnipper LE, Smith TJ, Raghavan D, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology identifies five key opportunities to improve care and reduce costs: The top five list for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1715–1724. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.8375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.